Abstract

To fully exploit the inherent and enduring potential of natural products for fundamental cell biology and drug lead discovery, synthetic methods for functionalizing unique sites are highly desirable. Here we describe a strategy for the derivatization of natural products at ‘unfunctionalized’ positions via Rh(II)-catalyzed amination enabling simultaneous structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies and arming (alkynylation) of natural products. Employing Du Bois C–H amination, allylic and benzylic C–H bonds underwent amination and olefins underwent aziridination. With tertiary amine-containing natural products, amidines were produced via C–H amination/oxidation and unusual N-aminations provided hydrazine sulfamate inner salts. The alkynylated derivatives are readied for subsequent conjugation to access cellular probes for mechanism of action studies. Both chemo- and site-selectivity was studied by application to a diverse set of natural products including the marine-derived anticancer diterpene, eupalmerin acetate (EPA). Quantitative proteome profiling with an alkynyl EPA derivative obtained by site-selective, allylic C–H amination led to identification of several protein targets in HL-60 cells, including several known to be associated with cancer proliferation, suggestive of a polypharmacological mode of action for EPA.

A renewed realization of the intrinsic value of bioactive small molecules isolated from natural sources, i.e. natural products, for drug discovery1 has spurred a renaissance in their study including novel concepts for their efficient synthesis,2 synthesis of natural product-like libraries,3 manipulation of biosynthetic pathways for synthetic biology, and incorporation into high throughput screens.4 This is not surprising given the high structural diversity, cell permeability, and high affinity commonly observed for cellular proteins of natural products which arguably explains why half the drugs in current clinical use are natural products or owe their intellectual origin to these bioactive small molecules.5 Furthermore, the enduring value of natural products for advancing knowledge in basic cell biology and their utility for the discovery of novel ‘druggable’ targets for human disease intervention cannot be understated. In particular, natural products continue to facilitate the identification of both activators and inhibitors of proteins encoded in the human genome in addition to a number of natural product-inspired molecules that are providing advances in this post-genomic era. 6,7 Given that current pharmaceuticals are thought to access < 500 of the estimated 3,000–10,000 potential therapeutic targets for human disease intervention,8 natural products hold great potential for discovery of novel cellular targets and drug discovery. One approach for fully exploiting this potential requires the synthesis of natural product conjugates that contain a covalently attached reporter tag, e.g. biotin or a fluorophore, appended by a flexible linker at a position in the natural product that does not abrogate binding to putative cellular receptor(s). However, natural products are often challenging to functionalize in a chemo- and site-selective manner because of their structural complexity, dense functionality, and commonly limited availability. One approach to access natural products with strategically placed linkers is through total synthesis, which enables access to novel and unique attachment sites, but this approach is not rapidly applied to access varied positions of complex natural products. Highly random derivatization techniques involving photo-cross-linking of natural products to affinity matrices have been reported, however these methods provide limited structure-activity relationship (SAR) data for subsequent drug development and no information regarding site of attachment in the event cellular targets are not captured.9 To fully exploit the inherent information content of complex, bioactive natural products, 10,11 mild and generally applicable microscale strategies for site selective derivatization of native natural products are required to enable SAR studies and the synthesis of natural product-based cellular probes. Such probes have proven useful for identifying the cellular targets of natural products and providing a molecular level understanding of how these small molecules exert their observed ameliorative or curative effects.7

We recently described several mild, microscale methods for simultaneous arming and SAR studies of natural products to address these issues including a Rh(II)-catalyzed OH and NH insertion of natural products bearing alcohols or amines,12,13 a mild In(III)-catalyzed iodination of arene-containing natural products,14 and cyclopropanations of natural products bearing both electron rich and deficient alkenes.15 These functionalization methods are dependent on the presence of native functional groups and are thus limited in terms of positional diversity. In addition, existing functional groups in natural products are often essential for maintaining biological activity. Therefore, methods that enable functionalization of C–H bonds would dramatically increase the purview of available sites on natural products for functionalization and improve possibilities of maintaining bioactivity of derivatives.

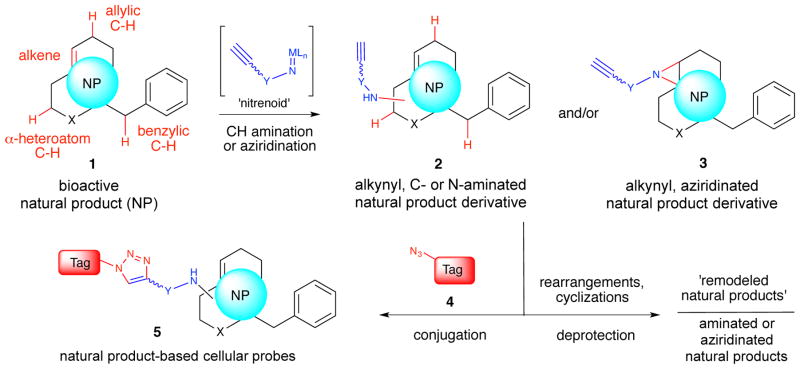

Several mild and chemoselective functionalizations of C–H bonds adjacent to aryl groups, alkenes, and heteroatoms (e.g. O, N) employing carbenoid or nitrenoid reagents in both an intramolecular and intermolecular fashion have recently been described.16 Of particular interest to our efforts were intermolecular Rh-catalyzed, C–H amination processes described by the groups of Du Bois,17,18 Lebel,19 and others via metallo nitrenoids,16 which can also deliver aziridines from electron-rich olefins with certain catalysts.20,21 We envisioned that the application of C–H aminations using a metal nitrenoid precursor bearing an alkyne to derivatize native, bioactive natural products would enable simultaneous arming and SAR studies of natural products at ‘unfunctionalized’ positions. The attached alkyne enables subsequent conjugation to various tags (e.g. biotin or fluorophores) providing natural product-based cellular probes useful for mode of action studies (Figure 1). In addition, rearrangements or cyclizations of C–H amination products could lead to ‘remodeled’ natural products22–24 while deprotection would lead to aminated or aziridinated natural products for SAR studies. Herein, we describe a two-step strategy for the functionalization of natural products at ‘unfunctionalized’ positions by Rh(II)-catalyzed amination or aziridination processes with an alkynyl sulfamate reagent which greatly expands the methods available for direct functionalization of native natural products. The described strategy provides a systematic approach for further exploiting natural products for chemical genetics and addressing the ‘small molecule target identification problem.’ The utility of this strategy is demonstrated by the identification of cellular targets of the anticancer marine natural product, eupalmerin acetate (EPA), by quantitative proteome profiling with an alkyne-substituted EPA derivative obtained by C–H amination.

Figure 1.

A two-step C–H Amination or Aziridination-Conjugation Sequence for Simultaneous Arming and SAR Studies of Natural Products.

In considering natural product derivatization via C–H amination, several issues were considered including the fact that intermolecular C–H amination is significantly more challenging than intramolecular processes,15 high chemo- and site (chemosite)12 selectivity is required for natural products which often bear multiple functional groups, and finally the requirement of microscale reaction conditions (≤ 1 mg) since natural products are often available in limited quantities. Mechanistic studies suggest that Rh-catalyzed C–H amination processes proceed through a concerted asynchronous transition state involving a rhodium nitrene reactant and follows the reactivity trend of 3° > α-amino > α-ethereal ≥ benzylic > 2° ≫ 1° C–H bonds.23

Results and Discussion

In our initial studies, we compared Du Bois and Lebel C–H amination conditions and were drawn to the former due to higher conversions observed with the use of only 1.0 equiv of nitrene precursor, which greatly simplifies purification despite the need for a stoichiometric oxidant. Building on Du Bois’ sulfamate design,17 we targeted a trichloroethyl substituted sulfamate with a terminal alkyne side-chain to enable subsequent conjugation to reporter tags. Du Bois previously described the use of trichloromethyl substitution on sulfamate nitrene precursors to prevent intramolecular C–H amination and facilitate mild, reductive deprotection to the primary amine. Therefore, we targeted sulfamate 9, which was readily prepared by a two-step sequence from commercially available trichloromethyl-β-lactone (Figure 2a). In control experiments, we verified the stability of the nitrene reagent sulfamate 9 since it could be recovered with good mass recovery. As an added benefit, trichloromethyl substitution provides a unique isotopic pattern to facilitate mass spectrometric identification of derivatized natural products.

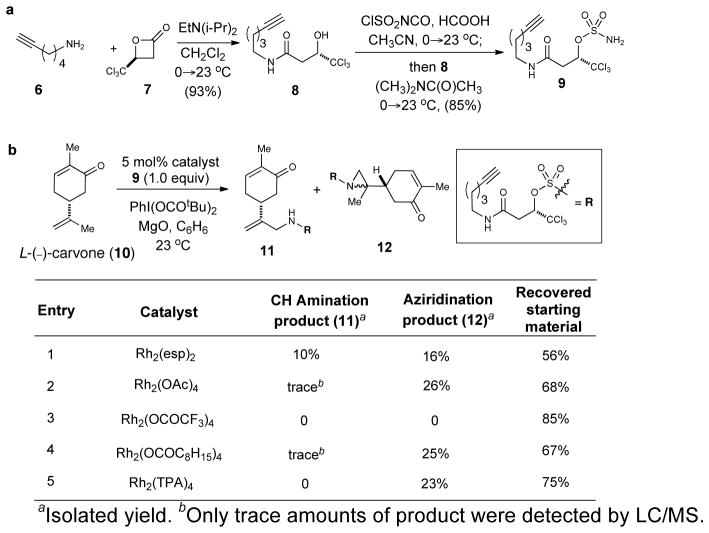

Figure 2. Synthesis of alkynyl sulfamate 9 and exploratory C–H amination with carvone.

a, Preparation of the nitrene precursor, alkynyl sulfamate 9. b, Catalyst screening for C–H amination versus aziridination with L-(−)-carvone 10.

For optimization studies, we chose carvone as a substrate, given the potential for both allylic C–H amination and alkene aziridination, and briefly studied various Rh(II) catalysts (Figure 2b). While Rh2(esp)2 gave both allylic C–H amination and aziridination in a combined 26% yield with 1.0 equiv of nitrene precursor 9, Rh2(OAc)4, Rh2(OCOC8H15)4 and Rh2(TPA)4 gave aziridination products exclusively in modest yields (23–26%) but with high mass recovery (Figure 2b). While conversions were generally modest, the mass recovery of these derivatizations was excellent. In general, we view lower conversion with good mass recovery as a tolerable balance when applying this reaction to sample-limited natural products. Furthermore, in comparison to overall yields likely to be obtained through de novo synthesis, the yield of these derivatives is quite acceptable.

While higher turnover numbers were reported by Du Bois when PhI(O2CCMe2Ph)2 was used as the oxidant,17 we found that PhI(O2CtBu)2 gave less complex reactions and both higher product yields and mass recovery. The addition of inorganic bases (e.g. K2CO3), Brønsted acids (e.g. HOAc) or Lewis acids (e.g. In(OTf)3) did not lead to significant increases in conversion, but did have a major impact on the chemoselectivity of the reactions. For example, Brønsted and Lewis acid additives (e.g. HOAc and In(OTf)3) favored C–H amination while the use of K2CO3 favored alkene aziridination, an observation important for altering chemoselectivity with complex natural products. Slow, dropwise addition of a dilute solution of the oxidant did not improve conversion and use of MgO had no impact on conversion or yields. Thus, direct addition of the solid oxidant in one portion enabled reaction at higher concentrations (~0.13 M), an important consideration for microscale derivatizations, and this procedure dramatically improved efficiency. While benzene was the optimal solvent, dichloromethane, and α, α, α-trifluorotoluene were also acceptable alternatives. Ultimately, conditions shown in the scheme in Table 1 (entry 1) were found to be optimal and these conditions were next applied in more complex settings.

Table 1.

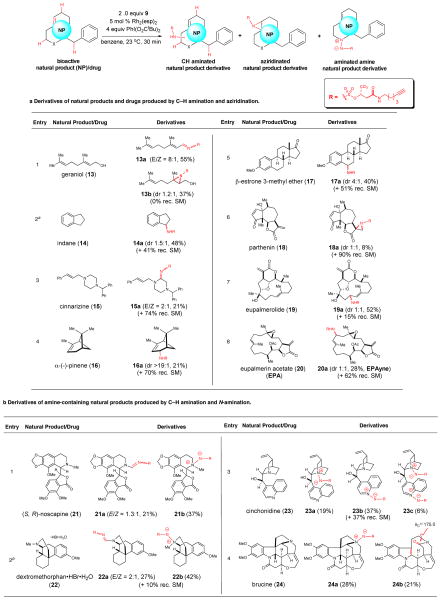

Simultaneous arming/SAR studies of natural products and drugs by amination and aziridination with sulfamate 9.

|

Diastereomers can be generated with achiral substrates, as in this case with indane, since the sulfamate reagent bears a stereogenic center.

C–H amination of dextromethorphan•HBr monohydrate was performed in the presence of K2CO3 (6.0 equiv). (rec. SM = recovered starting material)

Scope of the Rh2(esp)2 Catalyzed C–H Amination/Alkene Aziridination with a Diverse Set of Natural Products and Drugs

The optimized C–H amination/aziridination conditions were applied to several commercially available natural products and drugs. While conversions were modest in most cases as with carvone, mass recovery was again generally excellent. As expected, chemosite selectivity is highly substrate-dependent and the conformation of the natural products in benzene likely dictates accessible positions for C–H amination or aziridination in some cases overriding expected site selectivities based on electronic considerations.16 The structure and stereochemistry of derivatives was determined by extensive 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy (See Supplemental Materials).

Application of the optimized conditions to several natural products and drugs led to either C–H amination/oxidation, amination/dehydration, or aziridination (Table 1a). Functionalization of geraniol (13) gave a ~3:2 mixture of imine 13a (55%) and aziridine 13b (37%). To ensure that imine 13a (Table 1a, entry 1) was not derived from simple allylic oxidation by PhI(O2CtBu)2 and subsequent condensation of the resulting aldehyde with sulfamate 9, a control experiment without sulfamate was performed. This gave primarily epoxidation of geraniol rather than allylic oxidation. Thus, imine 13a may be derived from allylic C–H amination and subsequent dehydrative elimination. Aziridination of geraniol was site selective for the less electron rich alkene adjacent to the inductively electron-withdrawing alcohol suggestive of a possible directing effect by the allylic alcohol. Benzylic C–H amination of indane (14) occurred to give sulfamate 14a as previously observed with a simpler sulfamate.17 Cinnarizine (15) gave site selective C–H amination on the piperazine ring adjacent to the less hindered tertiary nitrogen providing amidine 15a presumably derived from subsequent oxidation of the initial C–H amination product (Table 1a, entry 3). α-Pinene (16) underwent highly facially selective allylic C–H amination leading to sulfamate 16a as a single diastereomer in 21% yield (Table 1a, entry 4). As with indane, benzylic C–H amination occurred with β-estrone 3-methyl ether (17) providing a 4:1 mixture of diastereomeric sulfamates 17a in 40% yield (Table 1a, entry 5). In the case of parthenin (18, Table 1a, entry 6), aziridination was observed exclusively at the electron-deficient alkene providing aziridines 18a as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers with low conversion. Selective allylic C–H amination occurred with both eupalmerolide (19) and eupalmerin acetate (EPA, 20) leading to the allylic sulfamates 19a/b and 20a/b as mixtures of diastereomers (dr ~1:1), respectively (Table 1a, entries 7,8).

Application of the amination conditions to amine-containing natural products led to either C–H amination/oxidation or a rare N-amination leading to a zwitterionic betaine (‘inner salt’),24,25 structurally verified following extensive 1H NMR (see Supplemental Table S1) and X-ray analysis of an N-aminated adduct (vide infra). The derivatization of (S,R)-noscapine led to C–H amination of the N-methyl group of the isoquinoline ring and subsequent oxidation to give amidine 21a (E/Z ~1:1, Table 1b, entry 1). In addition, amination of the isoquinoline nitrogen occurred to give betaine 21b. In a similar manner, dextromethorphan•HBr•H2O salt, in the presence of K2CO3 to provide the free base in situ, gave amidine 22a (E/Z ~2:1, Table 1b, entry 2) and betaine 22b. In the case of cinchonidine, N-amination was observed at the tertiary quiniculidine nitrogen, the quinoline nitrogen, and both positions leading to betaines 23a (verified by X-ray analysis, see Supplemental Figure S1), 23b, and 23c, respectively (Table 1b, entry 3). Brucine also led to amination of the tertiary amine to give betaine 24a and an eliminative oxidation with ring scission gave lactam 24b (diagnostic 13C signal at δ 175.0, see Supplemental for further characterization data) in 21% yield (Table 1b, entry 4).

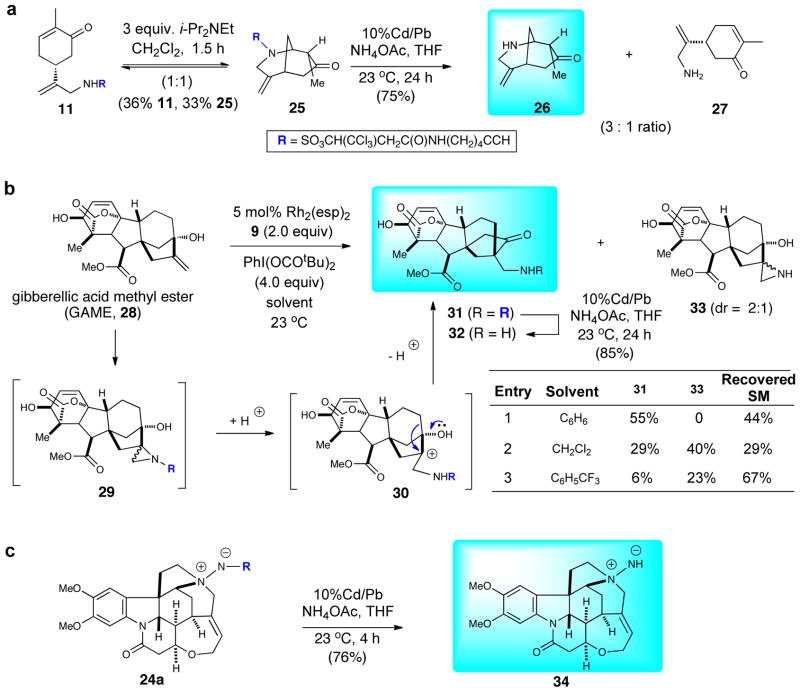

There is growing interest in structurally modifying or ‘remodeling’ natural products to identify new chemical entities for screening26 by controlling chemosite selectivity of derivatizations using minimal peptides27 or organometallic catalysts.12 In the course of these studies, we observed instances of unexpected cyclizations, rearrangements and insertions that led to novel natural product derivatives. As described above, brucine provided lactam 24b (Table 1b, entry 4) derived from a ring scission event. Carvone led to both allylic C–H amination and aziridination (Figure 2b, entry 1) as previously described. However, after prolonged storage or in the presence of base, the allylic sulfamate 11 underwent aza-Michael reaction to provide the interesting bicyclic carvone derivative 25 as an equilibrium 1:1 mixture with the starting allylic sulfamate (Figure 3a). Under standard conditions, gibberellic acid methyl ester (GAME, 28) did not give the expected aziridine (Figure 3b, entry 1), instead a ketone 31 was isolated in 55% yield (44% recovered starting material). We propose that initial aziridination occurred to give the expected aziridine 29, which underwent ring cleavage to afford a tertiary carbocation 30 and a subsequent 1,2-pinacol rearrangement delivered ketone 31 (see Figure 3b).28 In efforts to isolate the intermediate aziridine, a brief solvent study was undertaken and use of CH2Cl2 did deliver unprotected aziridine 33 in 40% yield accompanied by the rearranged ketone 31 (29%, Figure 3b, entry 2). Use of α,α,α–trifluorotoluene significantly suppressed the rearrangement (6%) and gave lower conversion to the unprotected aziridine 33 (23%, Figure 3b, entry 3).

Figure 3.

Natural Product Remodeling: (a) Cyclization of the carvone C–H amination product, (b) Rearrangement of gibberellic acid methyl ester derived aziridine and (c) Deprotection of betaines.

We studied removal of the alkynyl sulfamate by N–S cleavage leading to net addition of “NH” (aziridination) or “NH2” (C–H amination) to natural products, which could serve to improve water solubility of natural products. While several reductive methods for cleavage of trichloroethyl sulfamates could be applied,17 we chose the very mild conditions developed by Ciufolini employing 10% Cd/Pb couple.29 Deprotection of bicyclic ketone 25 under these conditions gave a 3:1 mixture of the expected deprotected azabicycle 26 and the ring-opened allylic amine 27 in 75% combined yield. Similarly, deprotection of the rearranged ketone 31 derived from gibberellic acid methyl ester (28) gave the primary amine 32 in 85% yield, and the deprotection of betaine 24a proceeded smoothly to give the fairly stable hydrazine inner salt 34 in 76% yield.

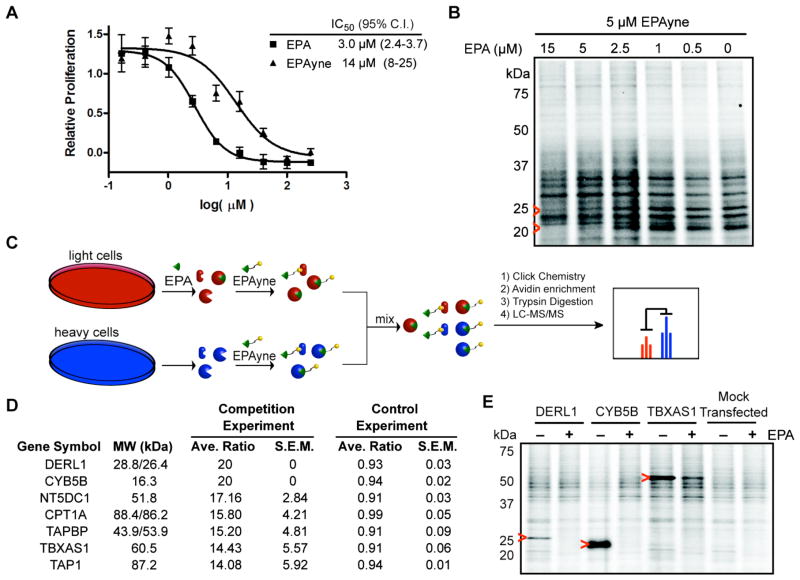

Quantitative proteomic profiling of eupalmerin acetate (EPA) targets in living HL-60 cells. EPA was previously shown to inhibit the proliferation of several cancer cell lines including leukemia, non-small cell lung, ovarian, breast, and colon cancer cell lines at sub- to low micromolar concentrations (GI50 0.34–1.7 mM) in the NCI 60 cancer cell line panel.30 EPA also showed significant growth suppression in a mouse model of malignant glioma xenografts.31 Despite the potential of EPA as an anticancer therapeutic, the exact cellular target(s) of EPA are unknown. To demonstrate the utility of the described natural product derivatization strategy and illustrate the concept of simultaneous SAR studies and arming of natural products, we considered application of quantitative proteomic profiling with the eupalmerin acetate-alkyne derivative (EPAyne) 20a (Table 1a, entry 8) to identify cellular targets of EPA in the HL-60 human acute myeloid leukemia cell line. Importantly, the described C–H amination of EPA modified the allylic position of the macrocycle far removed from the electrophilic exocyclic alkene, the presumed pharmacophore, likely serving as a Michael acceptor for nucleophilic residues of target proteins.

We first compared the antiproliferative properties of EPA and EPAyne in HL-60 cells, and found a decrease of only ~5 fold compared to EPA (IC50 3.0 vs 15 μM) suggesting that EPAyne could serve as a chemical probe to profile the cellular targets of EPA using quantitative, activity-based proteomic methods (Figure 4A). Thus, in the case of EPA, only one derivative, as a pair of diastereomers, was required for SAR studies to address the question of tolerable sites for modification.

Figure 4. Cytoxicity and Proteomic Profiling of EPA and EPAyne.

(A) Inhibition of HL-60 cell proliferation by EPA and EPAyne as measured using a WST-1 assay. (B) In situ treatment of HL-60 cells with EPAyne alone or in competition with EPA followed by conjugation to an azide-rhodamine reporter tag, SDS-PAGE, and fluorescent scanning. Red arrows highlight competed signals. (C) Schematic of competitive ABPP-SILAC. Cells are enriched with heavy or light isotopic tags and treated with DMSO or EPA, respectively, and followed by addition of EPAyne. EPA labeled proteomes are mixed, conjugated to biotin using click chemistry, enriched, and analyzed by MudPIT. (D) List of putative EPA targets in HL-60 cells. Average ratios are from duplicate runs and standard error results are reported. In the control experiment, heavy and light cells are treated with EPAyne alone (E) Validation of three high affinity targets DERL1, CYB5B, and TBXAS1 by labeling of transiently transfected 293T cells with EPAyne (5 μM) ± EPA (15 μM). Red arrows indicate the target’s expected molecular weight.

In order to profile specific EPA targets, we treated HL-60 cells with EPAyne (5 μM) and EPA (0–15 μM). Following this treatment, the cells were homogenized, and the probe adducts were conjugated to rhodamine-azide under copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition conditions,32 separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by in-gel fluorescent scanning. As shown in Figure 4B, several EPAyne bands are competed in a concentration-dependent manner by EPA, indicating that they are specific EPA targets. In order to identify these proteins, we performed competitive ABPP-SILAC, a quantitative, mass spectrometry (MS)-based chemoproteomic method that has been used to identify enzyme targets of activity based probes33,34 and small-molecules in cells35,36 and in vivo.33,35 Using competitive ABPP-SILAC, we observed several EPAyne targets that were competed by pretreatment with EPA, suggesting that these proteins are selective targets of EPA (Figure 4D, see also Supplemental Table S2). Interestingly, the high affinity target Derlin-1 (DERL1) is associated with cancer cell proliferation, while cytochrome b5 type B (CYB5B)37 and thromboxane A synthase (TBXAS1)38 are overexpressed in cancer. 39–43 The three aforementioned high affinity targets were confirmed by overexpression in 293T cells and demonstrated to interact specifically with EPAyne 20a since they were competed out with EPA in a concentration-dependent manner (20) (Figure 4E, Supplemental Figures S2A–B). Thus, EPAyne may prove to be a useful cellular probe to gain further understanding of the significance of these proteins in cancer proliferation. Another minor number of EPA targets are either completely uncharacterized (NUDT8, NT5DC1) or have unknown molecular functions (CDKAL1).

In summary, a method for performing simultaneous SAR studies and arming of bioactive natural products through Du Bois C–H amination and alkene aziridination is described using an alkynyl sulfamate nitrene precursor and Rh2(esp)2 as catalyst. These derivitizations are mild enough to tolerate a number of functional groups found in natural products including alcohols, ethers, lactones, lactams, esters, quinolines, and piperazines. In several cases, the described derivatization is found to be both chemo- and site selective enabling functionalization of allylic and benzylic positions via C–H amination or alkenes through aziridination. In addition, N-aminations of tertiary amines occur readily leading to inner salts and this process provides another avenue for tagging amine-containing natural products. Future studies will explore the potential utility of these inner salts for mode of action studies including proteomic profiling. For the purpose of SAR studies, the ability to initially obtain low chemosite selectivity is ideal to sample various positions of a given natural product in a tractable manner. In addition, attachment of an alkynyl substituent (‘arming’) enables direct conjugation of the derived natural product congeners to a variety of tags in a subsequent step. Mild conditions were identified for cleavage of the sulfamate group leading to net amination or aziridination of the parent natural product, which can improve water solubility when required. The utility of this method for natural product derivitization was demonstrated by application to eupalmerin acetate (EPA), a marine-derived anticancer diterpene with unknown cellular targets. A unique, allylic C–H aminated derivative of EPA (IC50 3.0 μM), coined EPAyne (IC50 15 μM), enabled in gel proteomic profiling of HL-60 cells providing initial analysis of cellular protein targets in this cancer cell line. Competitive ABPP-SILAC enabled quantitative proteome analysis of HL-60 cells and the identification of several cellular protein targets of EPA, including several associated with cancer proliferation. The described derivatization strategy greatly expands the methods available for direct functionalization of native natural products and provides a rapid and systematic approach for further exploiting natural products for chemical genetics and addressing the ‘small molecule target identification problem.’ Other emerging methods for direct C–H functionalization40,41 are also expected to be applicable and will potentially enable a truly universal approach for exploiting natural products for chemical genetics.26,46,47

Methods

Representative procedure for C–H amination/aziridination of complex natural products

The natural product or drug (0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sulfamate 9 (0.1 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and Rh2(esp)2 (0.0025 mmol, 0.05 equiv) were mixed in a small vial and evacuated under high vacuum for 10 min before being purged with N2. (Note: If the natural product/drug is volatile, it should be added after this evacuation process.) Benzene (0.4 mL) was added to give a green suspension (0.125 M) and this mixture was stirred at 23 °C under N2 for 10 min. PhI(O2CtBu)2 (0.2 mmol, 4.0 equiv) was then added in one portion and the reaction mixture was vigorously stirred at 23 °C for an additional 30 min. The crude reaction mixture, following initial analysis by LC-MS, was loaded on a silica gel column directly without workup and purified by flash column chromatography (eluting with EtOAc/Hexane) to isolate the desired product(s). For natural products only available in minute quantities, the reaction could be successfully performed on a 1 mg scale using 0.2 mL of solvent (concentration is ~20 mM in this case). The amount of all other reagents is reduced accordingly. If separation of sulfamate from product is problematic, it can be removed by extraction with 0.01 N aq. NaOH assuming stability of the natural product to these conditions. The reaction mixture is dissolved in CH2Cl2 and washed twice with 0.01 N aq. NaOH solution (0.2 volumes).

Competitive ABPP-SILAC

Briefly, HL-60 cells were cultured under isotopically ‘light’ conditions (with medium containing 12C614N2-lysine and 12C614N4-arginine) or ‘heavy’ conditions (with 13C615N2-lysine and 13C615N4-arginine). For competitions experiments, light and heavy cells were treated with EPA (15 μM) or DMSO, respectively, for 30 min and then subsequently treated with EPAyne (5 μM) for an additional 30 min. Cell proteomes were harvested and mixed (1:1), reacted under click chemistry conditions with biotin-azide, enriched with avidin beads, digested on-bead with trypsin and analyzed by liquid chromatography–tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) using an LTQ-Orbitrap instrument. Light and heavy signals were quantified from parent ion peaks (MS1) (See Supporting Info) and the corresponding proteins identified from product ion profiles (MS2) using the ProLuCID search algorithm.48 Control experiments, were carried out in the same manner with the exception that both heavy and light cells were treated with EPAyne alone.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (GM086307, D.R.; CA087660, B.C.; GM086271, to A.D.R.), a Ray Kathren American Cancer Society fellowship (J.S.C.), and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32GM095245-01 (J.S.C.) for support of this work. The Office of the Vice President for Research, the College of Science, and the Department of Chemistry at Texas A&M provided seed funding for the TAMU Natural Products LINCHPIN Laboratory. We thank Drs. Sergio Serna and Janet Rodríguez (Monterrey Inst. of Technology) for providing parthenin used in these studies. We thank Dr. Joe Reibenspies (Center for X-ray Analysis, TAMU) and Dr. Bill Russell (Laboratory for Biological Mass Spectrometry, TAMU) for securing structural and mass data, respectively.

Footnotes

Additional Information.

Synthetic procedures for natural product derivatization, full characterization data (including 1D and 2D NMR spectral data) for all new compounds, and biological and proteomic methods and data.

Author Contributions. D.R. and B.F.C. jointly conceived the study and supervised the work. D.R., B.F.C., J.L., J.S.C. and C.Z. were involved with design of the studies, performance of the experiments, and analysis of results; J.L., J.S.C., and D.R. wrote the manuscript; H.W. assisted with acquisition and analysis of 2D and cryoprobe NMR data; A.D.R. and B.V. isolated and purified samples of eupalmerolide and eupalmerin acetate and assisted with NMR analysis of resultant alkynylated derivatives. All authors edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Li JWH, Vederas JC. Drug discovery and natural products: End of an era or an endless frontier? Science. 2009;325:161–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1168243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newhouse T, Baran PS, Hoffmann RW. The economies of synthesis. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:3010–3021. doi: 10.1039/b821200g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For a recent special issue on this topic, see: Schreiber SL. Organic synthesis toward small-molecule probes and drugs, special feature. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2011;108:6699–6822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103205108.

- 4.Koehn FE. High impact technologies for natural products screening. Prog Drug Res. 2008;65:177–210. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8117-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdine L, Kodadek T. Target identification in chemical genomics: The (often) missing link. Chem Biol. 2004;11:593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson EE. Natural products as chemical probes. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:639–653. doi: 10.1021/cb100105c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:727–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanoh N, et al. Immobilization of natural products on glass slides by using a photoaffinity reaction and the detection of protein-small-molecule interactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:5584–5587. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piggott AM, Karuso P. Quality, not quantity: The role of natural products and chemical proteomics in modern drug discovery. Comb Chem High Throughput Screening. 2004;7:607–630. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terstappen GC, Schlüpen C, Raggiaschi R, Gaviraghi G. Target deconvolution strategies in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2007;6:891–903. doi: 10.1038/nrd2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peddibhotla S, Dang Y, Liu JO, Romo D. Simultaneous arming and structure/activity studies of natural products employing O–H insertions: An expedient and versatile strategy for natural products-based chemical genetics. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12222–12231. doi: 10.1021/ja0733686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chamni S, et al. Diazo reagents with small steric footprints for simultaneous arming/SAR studies of alcohol-containing natural products via OH insertion. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:1175–1181. doi: 10.1021/cb2002686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou CY, Li J, Peddibhotla S, Romo D. Mild arming and derivatization of natural products via an In(OTf)3-catalyzed arene iodination. Org Lett. 2010;12:2104–2107. doi: 10.1021/ol100587j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robles O, Serna-Saldívar SO, Gutiérrez-Uribe JA, Romo D. Cyclopropanations of olefin-containing natural products for simultaneous arming and structure activity studies. Org Lett. 2012;14:1394–1397. doi: 10.1021/ol300105q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies HML, Manning JR. Catalytic C–H functionalization by metal carbenoid and nitrenoid insertion. Nature. 2008;451:417–424. doi: 10.1038/nature06485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiori KW, Du Bois J. Catalytic intermolecular amination of C–H bonds: method development and mechanistic insights. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:562–568. doi: 10.1021/ja0650450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. Understanding the differential performance of Rh2(esp)2 as a catalyst for C–H amination. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7558–7559. doi: 10.1021/ja902893u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebel H, Huard K. De novo synthesis of Troc-protected amines: intermolecular rhodium-catalyzed C–H animation with N-Tosyloxycarbamates. Org Lett. 2007;9:639–642. doi: 10.1021/ol062953t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guthikonda K, Du Bois J. A unique and highly efficient method for catalytic olefin aziridination. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13672–13673. doi: 10.1021/ja028253a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebel H, Spitz C, Leogane O, Trudel C, Parmentier M. Stereoselective Rhodium-Catalyzed Amination of Alkenes. Org Lett. 2011;13:5460–5463. doi: 10.1021/ol2021516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appendino G, Tron GC, Jarevång T, Sterner O. Unnatural natural products from the transannular cyclization of lathyrane diterpenes. Org Lett. 2001;3:1609–1612. doi: 10.1021/ol0155541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis CA, Miller SJ. Site-selective derivatization and remodeling of erythromycin A by using simple peptide-based chiral catalysts. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5616–5619. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao H, et al. Ring-opening and ring-closing reactions of a shikimic acid-derived substrate leading to diverse small molecules. J Comb Chem. 2007;9:245–253. doi: 10.1021/cc060135m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F, et al. Iminonitroso Diels-Alder reactions for efficient derivatization and functionalization of complex diene-containing natural products. Org Lett. 2007;15:2923–2926. doi: 10.1021/ol071322b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Bois J. Rhodium-catalyzed C–H amination: Versatile methodology for the selective preparation of amines and amine derivatives. Chemtracts: Org Chem. 2005;18:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24.For an intramolecular example of N-amination with a sulfamate nitrene, see: Trost BM, Boyle O, Torres W, Ameriks MK. Development of a flexible strategy towards FR900482 and mitomycins. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:7890–7903. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003489.

- 25.For an example of N-amination via substitution using hydroxylamine derivatives, see: Gangapuram M, Redda KK. Synthesis of substituted N-[4(5-methyl/phenyl-1, 3, 4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-3,6-diphydropyridin-1(2H)-yl]benzamide sulfonamides as anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer agents. J Heterocycl Chem. 2009;46:309–316. doi: 10.1002/jhet.62.

- 26.Balthaser BR, Maloney MC, Beeler AB, Porco JA, Snyder JK. Remodeling of the natural product fumagillol employing a reaction discovery approach. Nat Chem. 2011;3:969–973. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan PA, Miller SJ. An approach to the site-selective deoxygenation of hydroxy groups based on catalytic phosphoramidite transfer. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2907–2911. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.For a related rearrangement of an epoxide derived from gibberellic acid methyl ester (28), see: Schreiber K, Schneider G, Sembdner G. Gibberlline-IX: Epoxydation von einigen gibberellinen. Tetrahedron. 1966;22:1437–1444.

- 29.Dong Q, Anderson CE, Ciufolini MA. Reductive cleavage of troc groups under neutral conditions with cadmium-lead couple. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5681–5682. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoemaker RH. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwamaru A, et al. Eupalmerin acetate, a novel anticancer agent from Caribbean gorgonian octocorals, induces apoptosis in malignant glioma cells via the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:184–192. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. A stepwise Hüisgen cycloaddition process: copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective “ligation” of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weerapana E, et al. Quantitative reactivity profiling predicts functional cysteines in proteomes. Nature. 2010;468:790–795. doi: 10.1038/nature09472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Everley PA, et al. Assessing enzyme activities using stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1771–7. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700057-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cisar JS, Cravatt BF. Fully functionalized small-molecule probes for integrated phenotypic screening and target identification. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10385. doi: 10.1021/ja304213w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ong SE, et al. Identifying the proteins to which small-molecule probes and drugs bind in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4617–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy D, et al. Constitutively overexpressed 21 kDa protein in Hodgkin lymphoma and aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas identified as cytochrome B5b (CYB5B) Mol Cancer. 2010;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cathcart MC, et al. Examination of thromboxane synthase as a prognostic factor and therapeutic target in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang JHH, et al. Derlin-1 is overexpressed in human breast carcinoma and protects cancer cells from endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R7. doi: 10.1186/bcr1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simamura ESH, Hatta T, Hirai KJ. Mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs) as novel pharmacological targets for anti-cancer agents. Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:213–7. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang CMC, Belinson JL, Vaziri S, Ganapathi R, Sengupta S. Role of the 18:1 lysophosphatidic acid-ovarian cancer immunoreactive antigen domain containing 1 (OCIAD)-integrin axis in generating late-stage ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1709–18. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michaudel Q, Thevenet D, Baran PSJ. Intermolecular Ritter-type C–H amination of unactivated sp3 carbons. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2547–2550. doi: 10.1021/ja212020b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai HX, Stephan AF, Plummer MS, Zhang YH, Yu JQ. Divergent C–H functionalizations directed by sulfonamide pharmacophores: late-stage diversification as a tool for drug discovery. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7222–7228. doi: 10.1021/ja201708f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masahiro A, Hisanor N, Shuinchi H. Catalytic C–H activation in total synthesis of natural products. CSJ Current Review. 2011;5:175–191. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu X, Liu Y, Park CM. Rhodium(III)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Annulation through C–H Activation: Total Synthesis of (±)-Antofine, (±)-Septicine, (±)-Tylophorine, and Rosettacin. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:9372–9376. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tayo LL, Lu B, Cruz LJ, Yates JR. Proteomic analysis provides insights on venom processing in Conus textile. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2292–301. doi: 10.1021/pr901032r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.