Introduction

The concept of fractional flow reserve (FFR) guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has gained worldwide acceptance in the cardiology community.1 Hemodynamic assessment using FFR in the cardiac catheterization laboratory is now routinely being performed in intermediate range coronary arterial stenoses to inform the decision to proceed with PCI.2 The paradigm of the FFR concept holds that clinical benefit of PCI is confined to coronary artery stenoses that restrict blood flow as documented by an abnormal FFR value (less than 0.75 or 0.80 typically).1 Correct measurement of FFR requires advancing a small wire distal to the stenosis which compares the intracoronary pressure to a proximal reference site under hyperemic conditions, e.g., after application of adenosine.3, 4 The procedure is invasive and adds cost, procedural time, radiation, contrast, as well as risk of vascular injury to standard angiography.5, 6 To overcome the limitation of an invasive procedure, enormous efforts are being undertaken to assess FFR noninvasively.7 Several clinical studies reported modest-good accuracy of obtaining FFR estimates by CT imaging while other efforts aim at combining coronary anatomic information with myocardial perfusion information to simulate the same, seemingly desirable, outcome.8, 9 Given the widespread use and large impact on the practice of cardiology, it appears prudent to critically review the evidence for the concept of FFR guided revascularization.

The FFR Rationale

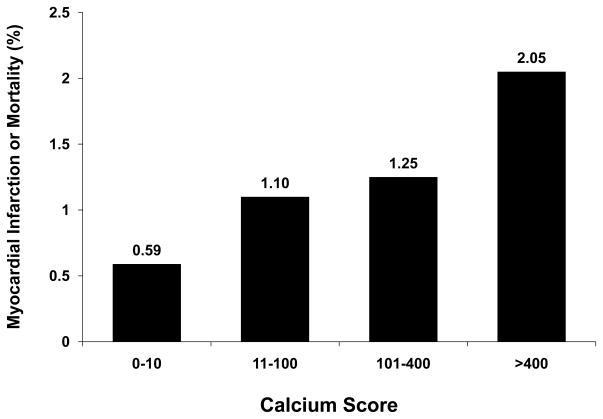

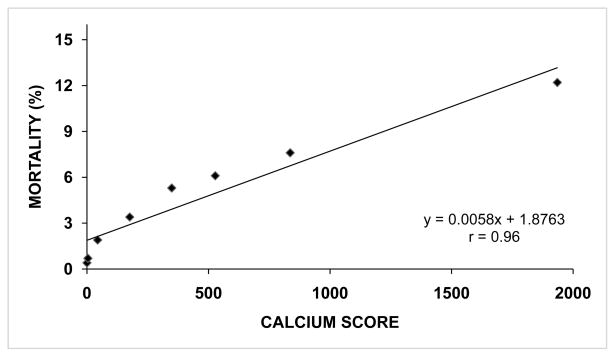

The FFR concept as outlined in the FAME (Fractional Flow Reserve vs. Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation) study is based on the premise that performing PCI on coronary arterial stenoses causing myocardial ischemia leads to reduced adverse cardiac events while it is not beneficial to revascularize lesions that do not cause ischemia.10 This premise, however, does not adequately consider the complicated relationship between coronary artherosclerotic disease, coronary arterial blood flow, myocardial ischemia, and adverse cardiac events. Depending on the characteristics of coronary atherosclerotic disease (e.g., diffuse vs. focal) and microvascular function, an FFR threshold of 0.8 may or may not be associated with myocardial ischemia.11 Thus, it may not be appropriate to equate prognosis of patients with abnormal FFR studies with those who exhibit evidence of myocardial ischemia. A more important and fundamental problem – most frequently overlooked - results from assigning poor patient outcome to either reduced coronary blood flow or myocardial ischemia without considering the extent of coronary artery disease itself as a critical confounder. Clearly, the presence and extent of myocardial ischemia on provokable testing is associated with worse outcome compared to patients without detectable ischemia.12 It is important to note, however, that prokocable myocardial ischemia is almost invariably associated with coronary artery disease - which then bears the question if it is the ischemia itself or the underlying coronary artery disease that confers risk of adverse events? This question is significant considering that appropriate patient management, as well as allocating research resources, hinge on its answer. Interestingly, few investigations include a detailed evaluation of both coronary anatomy and myocardial ischemia to allow meaningful insights into this association. The coronary atherosclerotic disease volume – a powerful predictor of patient outcome - is commonly not considered in older literature comparing angiographic and myocardial perfusion data.13–16 In studies employing both coronary calcium scanning – providing an estimate for the coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden - and stress testing in the same patients, the presence of calcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque conveys increased risk for subsequent cardiac events despite normal stress perfusion studies by SPECT17 or PET.18 Consistent with data from meta-analyses demonstrating an annual cardiac death and myocardial infarction rate of 1.8% with normal SPECT results in at risk populations,12 these results document high risk (exceeding 2%/year) for cardiac events in patients with severe coronary calcification despite normal stress myocardial perfusion results (Figure 1). Conversely, risk of myocardial infarction and death is exceedingly low (<0.2%/year) in patients without evidence of coronary atherosclerotic disease on angiography.19, 20 It is important to note that the risk of adverse events remains low in patients without significant coronary artery disease even in the presence of myocardial ischemia on provokable testing.20 The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study study – ironically often cited to support the opposite - reported no increased risk of myocardial infarction or death (albeit more repeat hospitalizations) after 3 years of follow up among symptomatic women who had evidence of myocardial ischemia but no obstructive coronary artery disease by coronary angiography.21 The aforementioned results are consistent with the paradigm that the most consistent marker of myocardial infarction/death risk is the presence and extent of the coronary atherosclerotic disease. This is impressively illustrated by the relationship between presence/extent of coronary artery calcium and mortality shown in more than 25,000 patients.22 This association does not reveal a “threshold” effect for myocardial ischemia but a near linear relationship between (calcified) coronary atherosclerotic disease burden and mortality risk (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Presented are the annualized rates (%) of total mortality or myocardial Infarction in patients with normal SPECT results in relation to coronary calcium scores. Event rates are only low (<10% ten-year risk) for patients with no or mild coronary calcification but high (>20% ten-year risk) for patients with calcium scores >400 despite normal stress test results. The figure was adapted and modified from Chang et al.17

Figure 2.

Rate of overall mortality (%) in 25,253 patients according to mean calcium score among predefined subgroups (0 (n=11,044), 1–10 (n=3,567), 11–100 (n=5,032), 101–299 (n=2,616), 300–399 (n=561), 400–699 (n=955), 700–999 (n=514), and ≥1000 (n=964). Data were derived from Budoff et al.22

The COURAGE (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) and other randomized trials have not demonstrated a reduction of myocardial infarction and death in patients with chronic angina, who underwent revascularization with resultant decreased ischemic burden on stress testing.23–25 A preliminary sub-analysis of the COURAGE trial suggested worse outcome in patients with large residual ischemic burden compared to those without; however, these results lost statistical significance after risk adjustments.26 Subsequent reports revealed that the extent of ischemia on stress testing at baseline did not predict adverse events or treatment effectiveness in the COURAGE population or in the BARI study.27, 28 Recent studies found no benefit of identifying provokable ischemia for guiding revascularization in high risk groups.29, 30 In a rare analysis of directly comparing atherosclerotic disease burden vs. myocardial ischemia for predicting myocardial infarction and death in patients with coronary artery disease, there was a consistent effect for disease burden but not for myocardial ischemia.31 Finally, a meta-analysis did not reveal a reduction of death or myocardial infarction in patients with documented provokable myocardial ischemia at time of enrollment who underwent PCI compared to medically treated patients.32 The ISCHEMIA trial (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches; NCT01471522) will be well positioned to conclusively disentangle the relationship between coronary anatomy and myocardial ischemia for guiding clinical management33 and the investigators should seize this opportunity, e.g., test the value of ischemia evaluation over an assessment of coronary artery disease burden for risk assessment and treatment effectiveness. Considering the available evidence, cardiac event risk is associated with stress induced myocardial ischemia primarily as the result of the underlying coronary artery disease and not of the ischemia itself.34 Indeed, it is time that we consider the emerging paradigm of atherosclerotic disease burden as the primary target of assessment and treatment in patients with coronary artery disease. Detecting myocardial ischemia on provokable testing foremost is a surrogate of the presence and severity of the underlying coronary artery disease with the latter being the actual substrate conferring risk for adverse events. This concept is well supported by our current understanding of the pathophysiology of acute coronary events.35 Acute coronary events occur as the result of plaque rupture or erosion which may trigger complete or partial coronary occlusion.36 The resultant acute myocardial ischemia -as opposed to ischemia with chronic angina in a conditioned myocardium which is usually well tolerated as evident by the safety of stress testing37–39 – may trigger arrhythmias as the result but not as the cause of acute coronary events.36 The risk of acute coronary events increases as a function of the extent and metabolic activity of the coronary atherosclerotic disease burden as well as the presence of factors enhancing the risk of an inadequate response to the stimulus for coronary arterial thrombosis.35 In conclusion, the underlying premise for the FFR concept is based on the common but erroneous assumption that provokable myocardial ischemia itself should be the target for intervention while the evidence and our understanding of acute coronary event pathophysiology strongly support coronary atherosclerotic disease and its characteristics to be the main determinants of risk. Considering the mechanisms leading to acute coronary events in conjunction with evidence from clinical studies, our goal for treatment of patients with stable coronary artery disease should be directed to “stabilizing” atherosclerotic disease and reducing the risk of a thrombosis permitting response35, 36, e.g., through risk factor interdiction, statin and antiplatelet therapy etc., with revascularization being reserved for the most extensive disease, e.g., left main or severe triple vessel coronary artery disease with compromised left ventricular systolic function,40 or crippling symptoms that are not controlled with adequate medication.

Studies in Support of the FFR Concept

The claim for clinical value from FFR testing largely rests on three clinical studies by the same core group of investigators: DEFER, FAME, and FAME2. Because of their impact, the studies should be discussed in detail.

DEFER

For the DEFER study 325 patients with stable, single-vessel coronary artery disease were randomized to either receive or defer PCI.41 The study design was complicated as patients crossed over to receive or defer PCI according to FFR data resulting in three final study groups: Defer (no PCI, FFR≥0.75), Reference (PCI, FFR<0.75), and Perform (PCI, FFR≥0.75). The authors reported a cardiac death and acute myocardial infarction rate of 3.3% in the Defer group after 5 years of follow up compared to 7.9% in the Perform group (15.7% in the Reference group) concluding that outcome in patients PCI of lesions with FFR ≥0.75 is not beneficial and should be discouraged. They further concluded that lesions with FFR <0.75 are associated with high risk for adverse outcome, suggesting that revascularization in such lesions is recommended. The latter, however, was not supported by the study data because a control group (no PCI, FFR <0.75) was not included in the study design. Eventually, this conclusion was disproved by the authors themselves in the FAME2 study which will be discussed later. The key problem, however, affecting the interpretation of DEFER (and also the FAME study) is the fact that the authors combined endpoints arising from revascularization procedures with those occurring spontaneously. Thirty-three percent of the Reference group underwent repeat revascularization procedures including 12% coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) compared to 21% of all repeat revascularization procedures (4.5% CABG) in the Perform group and only 17% of any revascularization in the Defer group (1% CABG). Because revascularization procedures are associated with risk of death and myocardial infarction, they increase the total number of events for the respective study group giving the impression of risk differences associated with FFR status (i.e., presence of ischemia) while they are actually explained by procedure utilization - driven by disease severity (the Reference group had more severe stenoses) and lesion location (as suggested by the different CABG rates). Particularly, for demonstrating the negative effects of PCI in patients without flow limiting disease – as the authors set out to do in DEFER – it would have been important to describe if events occurred spontaneously or were related to procedures. In summary, the DEFER study showed that performing PCI in lesions with FFR ≥0.75 does not provide clinical benefit over not performing PCI but it did not demonstrate that performing PCI in lesions with FFR<0.75 reduces events compared to deferring PCI. Thus, the value of using FFR assessment for clinical decision making was not established.

FAME

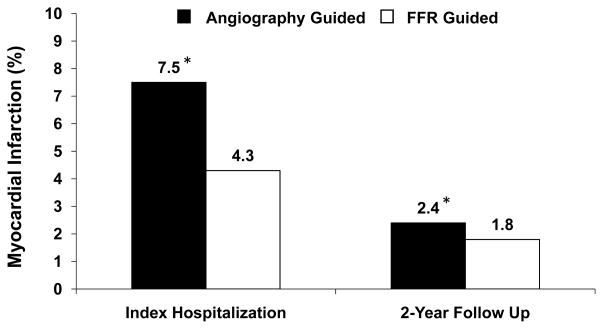

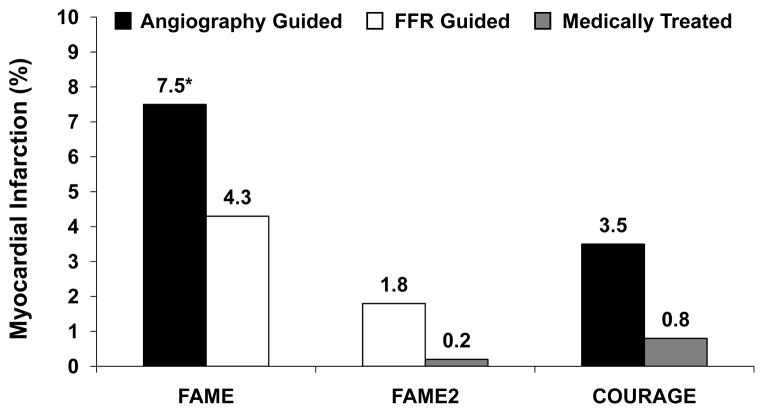

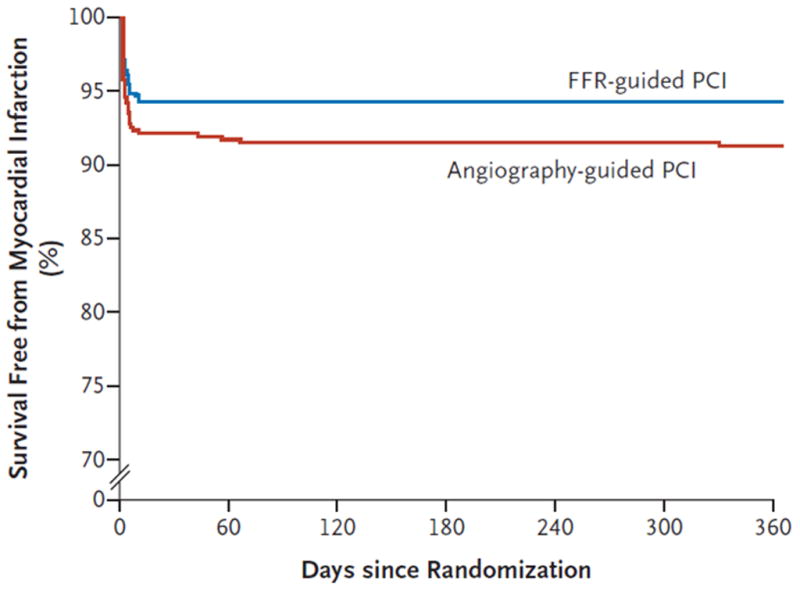

The impact of the FAME study10 on the field of cardiology has been immense. Not only did the FAME study lead to a paradigm shift in evaluating and managing patients with coronary artery disease1, it seemingly also provided the first supporting evidence from a randomized, prospective study for the clinical benefit of assessing coronary blood flow (as a surrogate for myocardial blood flow). The details of the FAME study are well known but are briefly reviewed here.42 For this study, 1005 patients with mostly stable, multivessel coronary artery disease were randomly assigned to an angiography vs. an FFR guided strategy for selecting lesions for PCI. Significantly more patients in the angiography guided group suffered an endpoint, consisting of myocardial infarction, death, or repeat revascularization at one year and the authors conveyed that FFR may be routinely used to identify coronary artery lesions that merit PCI. At first glance, the results appear impressive for the support of FFR in this setting. However, a close look at the Kaplan-Meier curve for myocardial infarction free survival reveals that all but very few events occurred within the first few days after randomization while the curves run parallel throughout the follow up (Figure 3). Since all initial PCI procedures were performed during the first few days post randomization, the preponderance of events during this time is explained by adverse events from invasive procedures, e.g., periprocedural events (Figure 4)43. Importantly, a liberal definition of myocardial infarction was used, i.e., ≥ 3 times upper limit of normal (ULN) for CK-MB regardless if occurring spontaneously or with procedures.10 While such definition was not inconsistent with clinical practice guidelines at that time,44 it resulted in a large number of myocardial infarctions, not commonly seen in interventional trials. For example, the COURAGE study reported less than half of the myocardial infarction rate associated with PCI in the entire 5 year follow up compared to the first few days in FAME (Figure 5).24 Interestingly, the authors emphasized that similar numbers (16 for angiography vs. 12 for FFR guided PCI) of small, prognostically controversial45 periprocedural myocardial infarctions (3–5 x ULN CK-MB) occurred in both groups which contrasts the distribution of events in the paper. To reconcile the authors’ statement with the Kaplan-Meier curves, many periprocedural infarcts had to be associated with > 5 x ULN to account for the large difference in myocardial infarctions during the index hospitalization (details on the breakdown of events were neither disclosed in the published articles nor on written requests). These details are indeed critical for interpreting the study results. Since patients in the FFR guided arm underwent fewer revascularization procedures than those in the angiography arm, the difference in patient outcome is well explained by fewer periprocedural events. This then bears the important question if the FFR results had any effect independent of merely reducing the number of PCIs? In other words: do we have evidence that FFR guidance resulted in fewer events compared to randomly reducing the number of PCIs (matched to the number of FFR procedures)? Since such control group was not included in the study design, we indeed have no such proof.

Figure 3.

Survival free from myocardial infarction (%) in the FAME study groups (angiography guided and FFR guided group). Note that almost the entire difference in myocardial infarction rates is due to events occurring during the first few days post randomization, i.e., at the time of the initial revascularization procedures, which were performed more frequently in the angiography group. The Figure was reproduced from Tonino et al.10 with permission. Abbreviations: FFR: fractional flow reserve.

Figure 4.

Rates of myocardial infarction (%) in the FAME study groups (angiography guided and FFR guided group) are shown for the index hospitalization and at 2-year follow up. Note that the reported difference in myocardial infarction rates is driven by the events occurring during the index hospitalization, i.e., the revascularization procedures, which were performed more frequently in the angiography group. There were also more late revascularization procedures performed in the angiography guided group, contributing to the number of myocardial infarctions at 2 years. Data were derived from the published results in the FAME and FAME follow up studies.10, 43 Asterisk indicates that these numbers were estimated from the reported total number of myocardial infarctions at 2 year follow up43 and from the Kaplan-Meier curve provided in the FAME study10. Abbreviations: FFR: fractional flow reserve.

Figure 5.

Rates of myocardial infarction (%) in the FAME and FAME2 studies associated with the index hospitalization (FAME) and within 7 days post randomization (FAME2) among patients undergoing PCI. While a breakdown of events is not provided in these publications, infarctions within the first few days of randomization can be largely attributed to periprocedural events as evident by the low number of myocardial infarctions in the medically treated arm in which only 4 PCIs were performed within 7 days. Note that the large difference in the number of myocardial infarctions in FAME vs. FAME2 persists even when accounting for the different number of interventions performed (1237 stents/496 patients [angiography guided] and 980 stents in 509 patients [FFR guided] in FAME vs. 728 stents in 435 patients in FAME2 [FFR guided]). These differences are explained by the altered definitions for myocardial infarction in these two trials which advantaged the FFR guided group in both cases. For comparison are shown the total numbers of periprocedural myocardial infarctions that occurred in the PCI and medical treatment strategy groups during 4.6 median follow up post randomization in the COURAGE trial. While the exact number of stenting procedures were not revealed, 41% of the 1006 patients undergoing PCI received more than one stent. Data were derived from the published results in the FAME, FAME2, and COURAGE studies.10, 24, 46 Asterisk indicates that this number was estimated from the Kaplan-Meier curve provided by Tonino et al.10 Abbreviations: FFR: fractional flow reserve. PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.

Contrary to the superficial impression, therefore, the FAME study demonstrates that FFR guidance of PCI merely results in lowering the number of coronary interventions with the associated reduction in periprocedural events but not to a reduction of hard events independent of revascularization procedures. Importantly, FAME did not provide evidence that FFR guidance more effectively reduces the number of interventions than simple random omission of PCI for the benefit of decreasing procedure associated myocardial infarction or death. Similar to the results from COURAGE, data from FAME demonstrated the safety of omitting PCI in the setting of stable, multivessel coronary artery disease.24 It is important to note that the outcome differences among the FAME study groups were largely augmented by a liberal definition of myocardial infarction leading to an unusually high number of infarcts during the index hospitalization when the vast majority of events occurred.

FAME2

To conclusively address the question of whether performing PCI in lesions with abnormal FFR results leads to better outcome compared to deferring PCI, a subsequent clinical study called “FAME2” was conducted.46 The FAME2 study specifically investigated the outcome among patients with hemodynamically significant coronary arterial stenoses – confirmed by FFR - who were randomly assigned to medical treatment or PCI.46 While the study found no difference in the occurrence of myocardial infarction or death among the groups, enrollment for this study was halted before its target enrollment based on an interim analysis revealing a significant increase in hospitalizations for chest pain and PCI in the medical treatment group. Again, a number of observations are important for adequate interpretation of the study results. Foremost, periprocedural myocardial infarctions were much more conservatively defined in FAME2 compared to FAME: > 10 ULN for CK-MB or > 5 ULN plus new Q waves or evidence of vessel occlusion or loss of myocardium.46 As a result of these much more stringent definitions, the number of periprocedural myocardial infarctions was more than 50% (even after adjusting for the different number of PCIs performed) smaller compared to FAME (Figure 5). It is reasonable to assume that the myocardial infarction rate for the FFR arm would have exceeded that of the medical treatment group if the same definition had been used as in FAME since this would have resulted in more periprocedural infarcts in patients receiving PCI at baseline. Such difference in myocardial infarction rate – favoring the medical treatment group - would have likely been even greater if medications were matched among groups. Patients undergoing PCI received clopidrogrel or prasugrel in addition to aspirin, resulting in 97% of patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy in the PCI arm vs. 46% in the medically treated group at 6 months. Given that there is evidence of reducing the number of myocardial infarctions with dual antiplatelet therapy in high risk patients even when not revascularized,47, 48 the unmatched medical treatment again favored the PCI group.

The inclusion of “unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization” in the composite end point has been widely criticized because of the inherent bias in this analysis.49 Patients with hemodynamically significant stenoses are known to require longer treatment times with medication for similar angina control compared to PCI.50 Importantly, both patients and treating physicians were not blinded to treatment allocation. Accordingly, patients were more likely to present to health care providers with persistent symptoms and physicians were more likely to perform PCI in patients with known unrevascularized disease.49 In support of this notion, only a minority of patients had unequivocal justification (i.e., biomarker elevation) for urgent revascularization in FAME2. Of 56 patients meeting this end point, only 12 (21%) had a myocardial infarction and 15 (27%) had ECG findings suggestive of ischemia while the majority of patients (52%) had neither evidence of ischemia nor myocardial infarction. Because of the ambiguity that is inherent in the diagnosis of unstable angina in the absence of objective evidence51 and because of the bias that affects both the patient and the provider in the setting of unblinded treatment, the endpoint of “unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization” should be interpreted with extreme caution or – preferably - disregarded altogether. The actual message of FAME2 is that even in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease – proven to be hemodynamically significant by FFR - myocardial infarction and death is not reduced by PCI despite methodology that substantially disadvantaged the medical therapy arm.33 The results of FAME2 therefore directly contradicted the conclusions made in DEFER and FAME.

Clinical Implications

The limitations of the FAME studies are sufficiently significant to seriously question the validity of the FFR guided PCI concept. Indeed, neither FAME nor FAME2 provided conclusive evidence that FFR guidance of PCI reduces myocardial infarction or death other than by lowering the number of PCIs – without providing proof that FFR guidance does so better than chance alone. The benefit of FFR is confined to identifying coronary arterial stenoses that trigger angina which indeed is helpful for avoiding PCI in lesions that would not result in symptomatic relief. The DEFER and FAME studies did demonstrate the absence of merit in performing PCI in coronary artery stenoses without hemodynamic significance which has led to decreasing numbers of stent procedures overall. This represents a major achievement of the FFR paradigm and an important step into the right direction. Unfortunately, the FAME study was misinterpreted in regards to the value of identifying flow limiting stenoses beyond symptom relief which has caused unjustified targeting of such lesions for diagnosis and treatment - while neglecting the attention to key determinants of risk, e.g., the characteristics of the underlying atherosclerotic disease. The FAME studies confirmed that PCI in patients with stable coronary artery disease leads to symptom relief but not to a reduction of myocardial infarction and death. Considering the current constraints of resources in health care, we should wonder if hundreds of thousands of PCIs each year are justified while most patients achieve a similar degree of symptom relief with medications within a few months.50 FFR testing may be best reserved for patients who have therapy resistant and/or severe angina as well as an ambiguous culprit lesion. Given that few patients fit these criteria, the value of FFR testing has been vastly overestimated.

The case of FFR guided PCI is revealing in many ways. In times of exploding knowledge and abundance of information, we are not immune to widely adopting concepts based on superficial reasoning. We need to ensure that concepts are congruent with our fundamental understanding of disease processes and that supporting evidence is solid before we apply them to our patients. We also live in times of increasing health care costs and expanding needs for more efficient, cost effective health care delivery. In the case of coronary artery disease, however, we continue to practice medicine that essentially ignores current evidence and practice guidelines.52, 53 With COURAGE, FAME2, and STICH (Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure), we have 3 recent major clinical studies in which patients with stable, multivessel coronary artery disease did not experience reduced rates of myocardial infarction or mortality with revascularization.24, 40, 46 A recent meta-analysis did not find a benefit of PCI over medical therapy in patients with coronary artery disease and associated myocardial ischemia.32 Nevertheless, the ‘occulo-stenotic reflex’54 – denying an adequate trial of medication - is as prevalent as ever leading to inflation of health care costs and many unnecessary procedures in patients.55 In a large contemporary US cohort, only 50% of non-acute PCIs were deemed appropriate – even when using rather liberal indication criteria.56 Given the current evidence, it is time that our practice guidelines more forcefully designate medical therapy as the default treatment for patients with stable coronary artery disease and discourage revascularization except for cases with the most severe disease or intractable symptoms despite adequate trials of anti-anginal medications.

Conclusions

The rationale for the FFR concept as outlined in the FAME study is based on a common misconception of the relationship between provokable myocardial ischemia and risk of adverse cardiac events. Current evidence supports such risk to be largely the result of the presence and extent of coronary atherosclerotic disease while provokable ischemia in stable patients merely serves as a surrogate for the underlying coronary artery disease. Contrary to widespread perception, there is no conclusive evidence for provokable myocardial ischemia as an independent predictor of outcome - while there is strong evidence for the atherosclerotic disease burden being independently predictive of adverse events. Two key observations from the FAME study challenge the notion of event reduction from FFR guided PCI: 1) the Kaplan-Meier curves for myocardial infarction free survival (which accounted for the difference in end points) unequivocally reveal that all but very few events occurred during the first few days after randomization, i.e., with revascularization procedures. 2) No evidence was provided that the benefit from FFR guidance – which predominantly resulted from fewer myocardial infarctions due to fewer PCIs performed in the FFR group – was superior to simply randomly reducing the number of PCIs. The misinterpretation of the FAME study led to an unjustified targeting of flow limiting stenoses for diagnosis and treatment which hinders an appropriate, comprehensive approach to patients with coronary artery disease. The benefit of FFR guided PCI is confined to assure symptom relief from the intervention. Since symptom relief also occurs with appropriate medications in most patients with stable angina, current resource constraints mandate a stronger support of medical therapy as the default treatment option in this setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: The author is supported by NIH grant K23-HL098368.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Mangiacapra F, Barbato E. From SYNTAX to FAME, a paradigm shift in revascularization strategies: the key role of fractional flow reserve in guiding myocardial revascularization. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2011;12:538–542. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328347edc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park SJ, Ahn JM. Should we be using fractional flow reserve more routinely to select stable coronary patients for percutaneous coronary intervention? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012;27:675–681. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328358f587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puymirat E, Muller O, Sharif F, Dupouy P, Cuisset T, de Bruyne B, Gilard M. Fractional flow reserve: concepts, applications and use in France in 2010. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van de Hoef TP, Meuwissen M, Escaned J, Davies JE, Siebes M, Spaan JA, Piek JJ. Fractional flow reserve as a surrogate for inducible myocardial ischaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:439–52. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.86. Epub 2013 Jun 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ntalianis A, Trana C, Muller O, Mangiacapra F, Peace A, De Backer C, De Block L, Wyffels E, Bartunek J, Vanderheyden M, Heyse A, Van Durme F, Van Driessche L, De Jans J, Heyndrickx GR, Wijns W, Barbato E, De Bruyne B. Effective radiation dose, time, and contrast medium to measure fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoole SP, Seddon MD, Poulter RS, Mancini GB, Wood DA, Saw J. Fame comes at a cost: a Canadian analysis of procedural costs in use of pressure wire to guide multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:262.e1–262.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor CA, Fonte TA, Min JK. Computational fluid dynamics applied to cardiac computed tomography for noninvasive quantification of fractional flow reserve: scientific basis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2233–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ, Berman DS, Koo BK, van Mieghem C, Erglis A, Lin FY, Dunning AM, Apruzzese P, Budoff MJ, Cole JH, Jaffer FA, Leon MB, Malpeso J, Mancini GB, Park SJ, Schwartz RS, Shaw LJ, Mauri L. Diagnostic accuracy of fractional flow reserve from anatomic CT angiography. JAMA. 2012;308:1237–1245. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rochitte CE, George RT, Chen MY, Arbab-Zadeh A, Dewey M, Miller JM, Niinuma H, Yoshioka K, Kitagawa K, Nakamori S, Laham R, Vavere AL, Cerci RJ, Mehra VC, Nomura C, Kofoed KF, Jinzaki M, Kuribayashi S, de Roos A, Laule M, Tan SY, Hoe J, Paul N, Rybicki FJ, Brinker JA, Arai AE, Cox C, Clouse ME, Di Carli MF, Lima JA. Computed tomography angiography and perfusion to assess coronary artery stenosis causing perfusion defects by single photon emission computed tomography: the CORE320 study. Eur Heart J. 2013 Nov 19; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht488. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van’t Veer M, Klauss V, Manoharan G, Engstrom T, Oldroyd KG, Ver Lee PN, MacCarthy PA, Fearon WF FAME Study Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gould KL, Johnson NP, Bateman TM, Beanlands RS, Bengel FM, Bober R, Camici PG, Cerqueira MD, Chow BJ, Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Gewirtz H, Gropler RJ, Kaufmann PA, Knaapen P, Knuuti J, Merhige ME, Rentrop KP, Ruddy TD, Schelbert HR, Schindler TH, Schwaiger M, Sdringola S, Vitarello J, Williams KAS, Gordon D, Dilsizian V, Narula J. Anatomic versus physiologic assessment of coronary artery disease. Role of coronary flow reserve, fractional flow reserve, and positron emission tomography imaging in revascularization decision-making. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1639–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navare SM, Mather JF, Shaw LJ, Fowler MS, Heller GV. Comparison of risk stratification with pharmacologic and exercise stress myocardial perfusion imaging: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2004.06.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marie PY, Danchin N, Durand JF, Feldmann L, Grentzinger A, Olivier P, Karcher G, Juilliere Y, Virion JM, Beurrier D. Long-term prediction of major ischemic events by exercise thallium-201 single-photon emission computed tomography. Incremental prognostic value compared with clinical, exercise testing, catheterization and radionuclide angiographic data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:879–886. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollock SG, Abbott RD, Boucher CA, Beller GA, Kaul S. Independent and incremental prognostic value of tests performed in hierarchical order to evaluate patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Validation of models based on these tests. Circulation. 1992;85:237–248. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berman D, Hachmovitch R. Risk assessment in patients with stable coronary artery disease: Incremental value of nuclear imaging. J Nuclear Cardiol. 1996;3:S41–S49. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(96)90207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900–2907. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072790.23090.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang SM, Nabi F, Xu J, Peterson LE, Achari A, Pratt CM, Mahmarian JF. The Coronary Artery Calcium Score and Stress Myocardial Perfusion Imaging Provide Independent and Complementary Prediction of Cardiac Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1872–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenker MP, Dorbala S, Hong EC, Rybicki FJ, Hachamovitch R, Kwong RY, Di Carli MF. Interrelation of coronary calcification, myocardial ischemia, and outcomes in patients with intermediate likelihood of coronary artery disease: a combined positron emission tomography/computed tomography study. Circulation. 2008;117:1693–1700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulten EA, Carbonaro S, Petrillo SP, Mitchell JD, Villines TC. Prognostic value of cardiac computed tomography angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1237–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papanicolaou MN, Califf RM, Hlatky MA, McKinnis RA, Harrell FE, Jr, Mark DB, McCants B, Rosati RA, Lee KL, Pryor DB. Prognostic implications of angiographically normal and insignificantly narrowed coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58:1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Kelsey SF, Sopko G, Rogers WJ, Mankad S, Sharaf BL, Bittner V, Bairey Merz CN. Persistent chest pain predicts cardiovascular events in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: results from the NIH-NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischaemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1408–1415. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, Flores FR, Callister TQ, Raggi P, Berman DS. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: observations from a registry of 25,253 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stergiopoulos K, Brown DL. Initial Coronary Stent Implantation With Medical Therapy vs Medical Therapy Alone for Stable Coronary Artery Disease -Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:312–319. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL, Chaitman BR, Shaw L, Gosselin G, Nawaz S, Title LM, Gau G, Blaustein AS, Booth DC, Bates ER, Spertus JA, Berman DS, Mancini GB, Weintraub WS COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pursnani S, Korley F, Gopaul R, Kanade P, Chandra N, Shaw RE, Bangalore S. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy in stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:476–490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.970954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, Mancini GB, Hayes SW, Hartigan PM, Weintraub WS, O’Rourke RA, Dada M, Spertus JA, Chaitman BR, Friedman J, Slomka P, Heller GV, Germano G, Gosselin G, Berger P, Kostuk WJ, Schwartz RG, Knudtson M, Veledar E, Bates ER, McCallister B, Teo KK, Boden WE COURAGE Investigators. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117:1283–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw LJ, Weintraub WS, Maron DJ, Hartigan PM, Hachamovitch R, Min JK, Dada M, Mancini GB, Hayes SW, O’Rourke RA, Spertus JA, Kostuk W, Gosselin G, Chaitman BR, Knudtson M, Friedman J, Slomka P, Germano G, Bates ER, Teo KK, Boden WE, Berman DS. Baseline stress myocardial perfusion imaging results and outcomes in patients with stable ischemic heart disease randomized to optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2012;164:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw LJ, Cerqueira MD, Brooks MM, Althouse AD, Sansing VV, Beller GA, Pop-Busui R, Taillefer R, Chaitman BR, Gibbons RJ, Heo J, Iskandrian AE. Impact of left ventricular function and the extent of ischemia and scar by stress myocardial perfusion imaging on prognosis and therapeutic risk reduction in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease: results from the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19:658–669. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9548-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panza JA, Holly TA, Asch FM, She L, Pellikka PA, Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Borges-Neto S, Farsky PS, Jones RH, Berman DS, Bonow RO. Inducible myocardial ischemia and outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aldweib N, Negishi K, Hachamovitch R, Jaber WA, Seicean S, Marwick TH. Impact of repeat myocardial revascularization on outcome in patients with silent ischemia after previous revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1616–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mancini GB, Hartigan PM, Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Hayes SW, Bates ER, Maron DJ, Teo K, Sedlis SP, Chaitman BR, Weintraub WS, Spertus JA, Kostuk WJ, Dada M, Booth DC, Boden WE. Predicting Outcome in the COURAGE Trial: Coronary Anatomy Versus Ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.10.017. Epub 2014 Jan 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stergiopoulos K, Boden WE, Hartigan P, Mobius-Winkler S, Hambrecht R, Hueb W, Hardison RM, Abbott JD, Brown DL. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Outcomes in Patients With Stable Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Ischemia: A Collaborative Meta-analysis of Contemporary Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:232–40. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torosoff MT, Sidhu MS, Boden WE. Impact of myocardial ischemia on myocardial revascularization in stable ischemic heart disease. Lessons from the COURAGE and FAME 2 trials. Herz. 2013;38:382–386. doi: 10.1007/s00059-013-3824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arbab-Zadeh A. Stress testing and non-invasive coronary angiography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: time for a new paradigm. Heart Int. 2012;7:e2. doi: 10.4081/hi.2012.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbab-Zadeh A, Nakano M, Virmani R, Fuster V. Acute coronary events. Circulation. 2012;125:1147–1156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2004–2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1216063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stuart RJ, Jr, Ellestad MH. National survey of exercise stress testing facilities. Chest. 1980;77:94–97. doi: 10.1378/chest.77.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vegh A, Szekeres L, Parratt JR. Protective effects of preconditioning of the ischaemic myocardium involve cyclo-oxygenase products. Cardiovasc Res. 1990;24:1020–1023. doi: 10.1093/cvr/24.12.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hambrecht R, Walther C, Mobius-Winkler S, Gielen S, Linke A, Conradi K, Erbs S, Kluge R, Kendziorra K, Sabri O, Sick P, Schuler G. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise training in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2004;109:1371–1378. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121360.31954.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, Jain A, Sopko G, Marchenko A, Ali IS, Pohost G, Gradinac S, Abraham WT, Yii M, Prabhakaran D, Szwed H, Ferrazzi P, Petrie MC, O’Connor CM, Panchavinnin P, She L, Bonow RO, Rankin GR, Jones RH, Rouleau JL STICH Investigators. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1607–1616. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pijls NH, van Schaardenburgh P, Manoharan G, Boersma E, Bech JW, van’t Veer M, Bar F, Hoorntje J, Koolen J, Wijns W, de Bruyne B. Percutaneous coronary intervention of functionally nonsignificant stenosis: 5-year follow-up of the DEFER Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2105–2111. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fearon WF, Tonino PAL, De Bruyne B, Siebert U, Pijls NHJ. Rationale and design of the fractional flow reserve versus angiography for multivessel evaluation (FAME) study. Am Heart J. 2007;154:632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pijls NH, Fearon WF, Tonino PA, Siebert U, Ikeno F, Bornschein B, van’t Veer M, Klauss V, Manoharan G, Engstrom T, Oldroyd KG, Ver Lee PN, MacCarthy PA, De Bruyne B FAME Study Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: 2-year follow-up of the FAME (Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, Katus HA, Newby LK, Ravkilde J, Chaitman B, Clemmensen PM, Dellborg M, Hod H, Porela P, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Beller GA, Bonow R, Van der Wall EE, Bassand JP, Wijns W, Ferguson TB, Steg PG, Uretsky BF, Williams DO, Armstrong PW, Antman EM, Fox KA, Hamm CW, Ohman EM, Simoons ML, Poole-Wilson PA, Gurfinkel EP, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Mendis S, Zhu JR, Wallentin LC, Fernandez-Aviles F, Fox KM, Parkhomenko AN, Priori SG, Tendera M, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Vahanian A, Camm AJ, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Morais J, Brener S, Harrington R, Morrow D, Lim M, Martinez-Rios MA, Steinhubl S, Levine GN, Gibler WB, Goff D, Tubaro M, Dudek D, Al-Attar N Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634–2653. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prasad A, Gersh BJ, Bertrand ME, Lincoff AM, Moses JW, Ohman EM, White HD, Pocock SJ, McLaurin BT, Cox DA, Lansky AJ, Mehran R, Stone GW. Prognostic significance of periprocedural versus spontaneously occurring myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes: an analysis from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, Barbato E, Tonino PA, Piroth Z, Jagic N, Mobius-Winckler S, Rioufol G, Witt N, Kala P, MacCarthy P, Engstrom T, Oldroyd KG, Mavromatis K, Manoharan G, Verlee P, Frobert O, Curzen N, Johnson JB, Juni P, Fearon WF FAME 2 Trial Investigators. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, Cacoub P, Cohen EA, Creager MA, Easton JD, Flather MD, Haffner SM, Hamm CW, Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Mak KH, Mas JL, Montalescot G, Pearson TA, Steg PG, Steinhubl SR, Weber MA, Brennan DM, Fabry-Ribaudo L, Booth J, Topol EJ CHARISMA Investigators. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1706–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boden WE. Which is more enduring--FAME or COURAGE? N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1059–1061. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1208620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weintraub WS, Spertus JA, Kolm P, Maron DJ, Zhang Z, Jurkovitz C, Zhang W, Hartigan PM, Lewis C, Veledar E, Bowen J, Dunbar SB, Deaton C, Kaufman S, O’Rourke RA, Goeree R, Barnett PG, Teo KK, Boden WE, Mancini GB COURAGE Trial Research Group, . Effect of PCI on quality of life in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:677–687. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez de Sa E, Lopez-Sendon J, Rubio R, Delcan JL. Validity of different classifications of unstable angina. Rev Esp Cardiol. 1999;52 (Suppl 1):46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, Berra K, Blankenship JC, Dallas AP, Douglas PS, Foody JM, Gerber TC, Hinderliter AL, King SB, 3rd, Kligfield PD, Krumholz HM, Kwong RY, Lim MJ, Linderbaum JA, Mack MJ, Munger MA, Prager RL, Sabik JF, Shaw LJ, Sikkema JD, Smith CR, Jr, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Williams SV, Anderson JL American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force. . 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012;126:e354–471. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318277d6a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katz MH. Evolving Treatment Options in Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:231. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Topol EJ, Nissen SE. Our preoccupation with coronary luminology. The dissociation between clinical and angiographic findings in ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:2333–2342. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weintraub WS, Boden WE, Zhang Z, Kolm P, Zhang Z, Spertus JA, Hartigan P, Veledar E, Jurkovitz C, Bowen J, Maron DJ, O’Rourke R, Dada M, Teo KK, Goeree R, Barnett PG Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program No. 424 (COURAGE Trial) Investigators and Study Coordinators. Cost-effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention in optimally treated stable coronary patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:12–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.798462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan PS, Patel MR, Klein LW, Krone RJ, Dehmer GJ, Kennedy K, Nallamothu BK, Weaver WD, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Brindis RG, Spertus JA. Appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;306:53–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]