Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the effect of histopathological lesion characteristics on the sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for per-lesion identification of extracapsular extension (ECE) of prostate cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study included 176 patients (median age 58.9 years, range 38–77) who underwent endorectal MRI before radical prostatectomy between January 2001 and July 2004, had no previous treatment and had whole-mount step-section pathological specimens showing at least one capsule-abutting lesion. The likelihood of ECE of capsule-abutting lesions was retrospectively scored from 1 to 5 based on radiologists’ prospective MRI interpretations. Generalized estimating equation regression models were used to determine the effect of the following histological variables on the sensitivity of MRI for identifying ECE of capsule-abutting lesions: maximum diameter, largest perpendicular diameter (LPD), bi-dimensional diameter product, Gleason grade, and zonal extent.

RESULTS

On histopathology, 339 capsule-abutting lesions were found, including 54 with ECE. MRI correctly identified ECE in 36/54 capsule-abutting lesions, including nine of 18 with focal ECE and 27/36 with established ECE, giving sensitivities (95% confidence interval) of 67 (53–78)%, 50 (27–73)% and 75 (58–87)%, respectively. MRI incorrectly identified ECE in 27/285 (9%) capsule-abutting lesions without ECE. MRI sensitivity for per-lesion ECE identification was significantly associated only with histopathological LPD (P = 0.009). Fifty-one patients (29%) had ECE. MRI had a sensitivity (95% confidence interval) of 69 (54–81)% and specificity of 90 (83–94)% for per-patient ECE identification.

CONCLUSIONS

The sensitivity of MRI in per-lesion identification of prostate cancer ECE is significantly associated with the lesion LPD at histopathology.

Keywords: prostate cancer, MRI, extracapsular, extension

INTRODUCTION

In patients with prostate cancer, tumour extension outside the prostate capsule is a negative prognostic factor, associated with an increased likelihood of cancer recurrence [1]. Patients thought to have no or minimal extracapsular extension (ECE) can be considered candidates for a variety of local therapies, whereas patients believed to have substantial ECE can be considered candidates for radiotherapy or non-curative systemic therapies. Accurate identification of ECE of prostate cancer is therefore important for appropriate treatment selection, treatment planning and patient counselling [2,3].

Histopathologically, ECE is defined as a cancer that extends through the prostatic capsule into the periprostatic adipose tissue. ECE is further subdivided into focal ECE and established ECE. Focal ECE refers to the presence of no more than a few malignant cells immediately outside the capsule (i.e. within one or two step-sections). Established ECE refers to all other cases of ECE and includes more extensive presence of malignant cells outside the capsule [4,5].

MRI criteria for ECE have been reported previously and include a contour deformity with a step-off or angulated margin, an irregular capsular bulge or retraction, a breach of the capsule with evidence of direct tumour extension, obliteration of the rectoprostatic angle, and asymmetry of the neurovascular bundles [6]. The ability of MRI to identify ECE has typically been assessed on a per-patient or per-site (quadrant or sextant) basis [7–13]. Engelbrecht et al. [7] reported that the accuracy of MRI in identifying ECE was higher per patient than it was per site. Several recent pathology and imaging publications suggested that measuring the radial diameter of ECE could have important implications in identifying treatment strategies for patients with localized prostate cancer [14,15].

The increased use of PSA screening has led to a marked reduction in prostate tumour volume and stage at the time of diagnosis [13]. Therefore, the above-mentioned morphological criteria for identifying ECE on MRI are being encountered less often in clinical practice. Especially in the surgical group, many patients with prostate cancer have either very subtle or no apparent capsular changes to indicate ECE on MRI. To our knowledge, there are no in-depth studies on how histopathological characteristics of prostate cancer, including longest diameter, largest perpendicular diameter (LPD), bi-dimensional diameter product (BDDP), Gleason grade, or zonal extent on whole-mount step-section pathology, affect the sensitivity of MRI in detecting ECE. The purpose of the present study was to assess the effect of histopathological lesion characteristics on the sensitivity of MRI for the per-lesion detection of ECE of prostate cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The institutional review board approved our study and issued a waiver of informed consent for the retrospective review of the MRI reports and clinical data of 455 consecutive patients who, between January 2001 and July 2004, underwent endorectal MR followed by radical prostatectomy (RP) at our institution, with subsequent step-section pathological evaluation, and for whom whole-mount step-section pathological specimens were available. Of these patients, 279 were excluded from the study because they did not meet one or both of the inclusion criteria, i.e. no neoadjuvant hormonal or radiation treatment received before RP; and at least one pathologically confirmed capsule-abutting lesion. In all, 176 patients (median age 58.9 years, range 38–77) were included in the study, which was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

For each patient, the whole-mount histopathology tumour map obtained from the institutional pathology database served as the reference standard. All RP specimens were inked with India ink tattoo dye (green dye on the right, blue dye on the left) and fixed in 10% formalin for 36 h. The distal 5 mm of the apex was amputated and coned. The rest of the gland was serially sectioned from apex to base to acquire axial slices at 3-mm intervals (axial step sections) and submitted in its entirety for paraffin embedding as whole mounts. The seminal vesicles were amputated and submitted separately. After paraffin embedding, microsections were placed on glass slides and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. The axial pathological sections were numbered consecutively from apex to base. Cancer foci were outlined in ink on whole-mount slices, including apices and seminal vesicles, so as to be grossly visible and were then photographed to provide tumour maps [16]. The extent of ECE on pathological specimens was determined as previously described [17]. The presence of cancer cells beyond the capsular margin extending into the periprostatic adipose tissue was used as the definition of ECE, as previously described by Ohori et al. [5]. ECE was further subdivided into focal and established ECE. On whole-mount step-section pathological maps, for each capsule-abutting lesion, the maximum diameter and the LPD at histology were measured, and the BDDP was calculated. The location, zonal distribution, and Gleason grade of each capsule-abutting lesion were also recorded.

For endorectal MRI we used a 1.5-T unit (Signa Horizon; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA), with patients examined while supine. A body coil was used for excitation and a pelvic phased-array coil (GE Medical Systems) combined with a commercially available balloon-covered expandable endorectal coil (Medrad, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was used for signal reception. Transverse T1-weighted spin-echo MR images were obtained from the aortic bifurcation to the symphysis pubis with the following parameters: TR/TE, 700/8 ms; section thickness, 5 mm; intersection gap, 1 mm; field of view, 24 cm; matrix, 256 × 192; and frequency direction, transverse (to prevent obscuring the pelvic lymph nodes from endorectal coil motion artefact). One signal was acquired. Transverse, sagittal and coronal thin-section high-spatial-resolution T2-weighted fast spin-echo MR images of the prostate and seminal vesicles were obtained with the following parameters: TR/effective TE, 5000/96 ms; echo train length, 16; section thickness, 3 mm; intersection gap, 0 mm; field of view, 14 cm; matrix, 256 × 192; frequency direction, anteroposterior (to prevent obscuring the prostate from endorectal coil motion artefact); and signals acquired, three. All MRI data were transferred to the picture archiving and communication system (GE Medical Systems) of our radiology department.

Each MRI study was prospectively interpreted by one of seven attending body-imaging radiologists; images were interpreted independently during the regular clinical assignment of each radiologist to the MRI service. Six of the readers had completed Fellowships in body imaging that included MRI of the prostate. The experience of these six radiologists in reading MR images since their fellowship training ranged from 1 to 13 years. The seventh reader had >20 years of experience interpreting MR images. As per regular clinical practice, the readers were not unaware of the clinical data, including PSA levels and biopsy results. Each radiologist made his or her determination of the presence of ECE on the basis of knowledge of previously described MRI features of ECE, such as an irregular capsular bulge, periprostatic fat infiltration, obliteration of the retroprostatic angle, and asymmetry or direct involvement of the neurovascular bundles [6,18–20]. On the basis of the radiologists’ written reports, one author unaware of the clinical and imaging data, retrospectively scored the likelihood of ECE in each lesion on a five-point scale as follows: score 1, no ECE; score 2, probably no ECE (cannot be excluded, although there is no clear evidence of it); score 3, possible ECE (a lesion is suspected of showing ECE); score 4, probable ECE (a lesion is strongly suspected of showing ECE); score 5, definite ECE. During this scoring, the lesions detected on MRI were matched with the lesions on the corresponding whole-mount step-section pathological maps.

To examine differences in the distribution of histopathological characteristics between patients with and without pathologically confirmed ECE, a Pearson’s chi-square test, with a second-order correction proposed by Rao [21] to adjust for patients with multiple lesions, was used. For continuous variables, an adjusted Wald test was used. To determine whether any of the variables had a significant univariate effect on the ability to detect ECE on MRI we used generalized estimating equation regression, modelling the sensitivity as a function of each variable:

log(sensitivity) = β0 + β1 Metrics

where metrics refers to the variable of interest (such as maximum diameter, etc.). To illustrate the effect of the LPD on the sensitivity of MRI for detecting ECE we calculated predicted sensitivities from the above model for each of the lesions and plotted the predictions against the LPD.

RESULTS

Of the 176 patients included in the study, 51 (29%) had ECE; 16 (9%) had focal ECE and 35 (20%) had established ECE. On whole-mount step-section pathology, 577 prostate cancer foci were found in the 176 patients; 339/577 lesions (59%) were found to abut the capsule of the prostate. Of the 339 capsule-abutting tumours, 272 (80%) were in the peripheral zone (PZ), 36 (11%) were in the transition zone (TZ), 20 (6%) were predominantly in the PZ but extended to the TZ, and 11 (3%) were predominantly in the TZ but extended to the PZ (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the capsule-abutting lesions on the whole-mount step-section pathological maps and MRI

| Median (range) or n (%) variable |

All lesions (339) |

Lesions with ECE (54) |

Lesions without ECE (285) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological map | |||

| LPD, cm | 0.60 (0.10–8.0) | 1.40 (0.30–3.5) | 0.50 (0.10–8.0) |

| Maximum diameter, cm | 1.29 (0.20–4.6) | 2.57 (1.0–4.6) | 1.10 (0.20–4.1) |

| BDDP, cm2 | 0.84 (0.02–19.2) | 3.39 (0.48–15.8) | 0.60 (0.02–19.2) |

| Zonal distribution | |||

| PZ | 272 (80) | 38 (69) | 234 (82) |

| TZ | 36 (11) | 6 (11) | 30 (11) |

| PZ + TZ | 20 (6) | 7 (13) | 13 (5) |

| TZ + PZ | 11 (3) | 3 (6) | 8 (3) |

| Gleason category | |||

| 3 + 3 | 222 (65) | 6 (11) | 216 (76) |

| 3 + 4 | 70 (21) | 20 (37) | 50 (18) |

| 4 + 3 | 26 (8) | 14 (26) | 12 (4) |

| 4 + 4 | 10 (3) | 4 (7) | 6 (2) |

| 4 + 5 | 7 (2) | 7 (13) | – |

| 5 + 4 | 4 (1) | 3 (6) | 1 (<1) |

| Positive margins | 50 (15) | 23 (43) | 27 (9) |

| Margin length, cm | 1.05 (0.01–25.0) | 1.2 (0.01–25.0) | 1.0 (0.10–19.4) |

| MRI | |||

| Zonal distribution | |||

| PZ | 159 (47) | 34 (63) | 125 (44) |

| TZ | 9 (3) | 2 (4) | 7 (2) |

| PZ + TZ | 14 (4) | 7 (13) | 7 (2) |

| TZ + PZ | 8 (2) | 3 (6) | 5 (2) |

| Unidentified on MRI | 149 (44) | 8 (15) | 141 (49) |

| ECE score on MRI | |||

| 1 (lesion not seen on MRI) | 149 (44) | 8 (15) | 141 (49) |

| 1 (lesion seen, graded 1) | 121 (36) | 8 (15) | 113 (40) |

| 2 | 6 (2) | 2 (4) | 4 (1) |

| 3 | 13 (4) | 0 (0) | 13 (5) |

| 4 | 23 (7) | 9 (17) | 14 (5) |

| 5 | 27 (8) | 27 (50) | 0 |

PZ + TZ, predominantly in the PZ with extension to the TZ; TZ + PZ, predominantly in the TZ with extension to the PZ.

A median (range) of 2 (1–9) capsule-abutting lesions was present in each patient. Fifty-four of the 339 capsule-abutting lesions (16%) had ECE at pathology (18 had focal ECE and 36 established ECE). Table 1 also shows the distribution of MRI findings for capsule-abutting lesions. Considering MRI scores of 4 and 5 as indicating the presence of ECE, the overall sensitivity (95% CI) of MRI for identifying ECE of capsule-abutting lesions was 36/54, or 67 (53–78)%. MRI identified nine of 18 instances of focal ECE, for a sensitivity of 50 (27–73)%, and 27 of 36 instances of established ECE, for a sensitivity of 75 (58–87)%. MRI yielded false-positive findings of ECE for 27 (9%) of 285 capsule-abutting lesions without ECE.

The sensitivity of MRI in detecting ECE was not significantly associated with the maximum diameter (P = 0.92), BDDP (P = 0.42), Gleason grade (P = 0.43) or zonal extent (P = 0.30) of capsule-abutting lesions at histopathology. The sensitivity of MRI for detecting ECE was significantly associated with the LPD of prostate cancer lesions measured at histopathology (P = 0.009; Table 2). For capsule-abutting lesions with a LPD of >2 cm, the predicted sensitivity was ≈0.71 (Fig. 1). For lesions with a LPD of >3 cm, the predicted MRI sensitivity was >0.84.

TABLE 2.

Results of univariate generalized estimating equation models to determine the association between geometric features of tumour measured at histopathology and the ability to identify ECE by MRI

| Measured covariate | Parameter estimate* | Relative fraction (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum diameter | 0.01 | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | 0.92 |

| LPD | 0.17 | 1.18 (1.04–1.34) | 0.009 |

| BDDP | 0.02 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.42 |

From the marginal generalized linear regression model: log(identification rate) = β0 + β1 × metrics.

FIG. 1.

Relationship between model-based predicted MRI sensitivity in detecting ECE of prostate cancer and the LPD of the prostate cancer lesion on whole-mount step-section pathology. The plot of sensitivity by LPD is from the model-based estimates. The model is based on sensitivity, which is the probability that MRI correctly detected ECE, over all lesions that had ECE. Each dot can represent more than one lesion, but no dot represents more than three lesions.

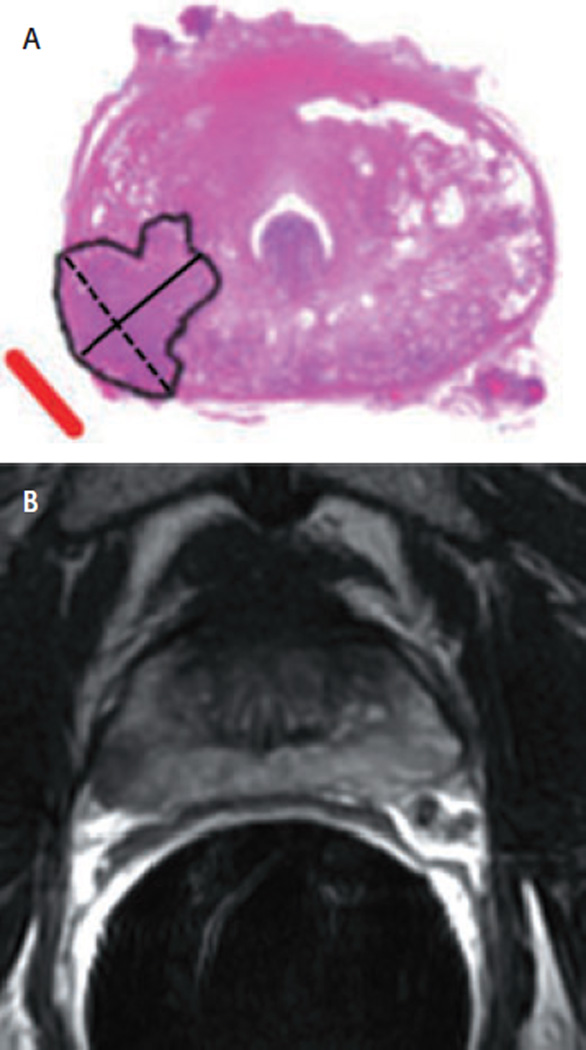

Figure 2 shows the histopathological map and MR image from a patient with a tumour abutting the prostate capsule. ECE was identified on the MRI studies. Figure 3 shows the histopathological map and MR image from a patient with a capsule-abutting lesion in whom ECE was found at neither imaging nor pathology.

FIG. 2.

A, Whole-mount step-section pathological map of the prostate of a 60-year-old man with clinical stage T1c prostate cancer and a PSA level of 4.8 ng/mL, showing Gleason grade 3 + 4 tumour in the right PZ; maximum diameter 1.8 cm (dotted line); LPD 1.6 cm (solid line); BDDP 2.9 cm2. The red line indicates ECE. B, Transverse T2-weighted MR image shows the tumour with capsular bulging and irregularity indicating ECE.

FIG. 3.

A, Whole-mount step-section pathological map of the prostate of a 51-year-old man with clinical stage T2a prostate cancer and a PSA level of 5.1 ng/mL, showing Gleason grade 3 + 3 tumour in the right PZ; maximum diameter 1.8 cm (dotted line); LPD 0.4 cm (solid line); BDDP 0.7 cm2. There was no evidence of ECE. B, Transverse T2-weighted MR image shows no ECE at the right lateral prostate capsule.

DISCUSSION

Most patients with clinically localized prostate cancer undergo some type of local therapy in an attempt to cure the disease [4]. However, because ECE is an important negative prognostic factor, treatment selection and planning can be altered if ECE is thought to be present [4,13,22,23]. Although several typical MRI features of ECE have been identified [6], our study, which analysed findings for very many lesions and used whole-mount, step-section histopathology maps as the reference standard, shows that the detection of focal ECE on MRI remains especially difficult. In identifying ECE among 339 capsule-abutting lesions found at histopathology, the sensitivity of MRI was 75% for established ECE but only 50% for focal ECE.

At histopathological examination of RP specimens, tumour characteristics such as volume, Gleason grade, and pathological stage have been associated with the level of invasion into or through the prostatic capsule, and with the rate of recurrence after RP [17]. We assessed whether the location, zonal distribution and Gleason grade, as well as the maximum diameter, LPD and BDDP of capsule-abutting lesions at histopathology were associated with the detection of ECE on MRI. The maximum diameter, LPD and their product are tumour measures widely used in assessing treatment response on planar imaging according to a method proposed by the WHO [24]. These tumour measures have also been used at pathology [25]. Of all the histopathological tumour characteristics we assessed, only the LPD was significantly associated with the sensitivity of MRI for identifying ECE. Specifically, the predicted sensitivity of MRI detection increased from ≈0.71 for capsule-abutting lesions with a LPD of >2 cm, to >0.84 for lesions with a LPD of >3 cm. Our data also showed that lesions with ECE were more likely to be associated with positive surgical margins (43% in capsule-abutting lesions with ECE vs 9% in capsule-abutting lesions without ECE).

Previously, Ellis et al. [26] investigated anatomical and histopathological characteristics of prostate cancer lesions that enhanced detection by MRI or TRUS. They found that a posterior location at histopathological examination was the most important factor in detecting cancers with either imaging technique. Tumour dimensions and high Gleason scores also affected detection but were an order of magnitude less important. A limitation of their study was that MR images were obtained with a body coil. In the present study MRI was done with both phased-array and endorectal coils, an approach that markedly improves image quality.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was retrospective, and the original clinical MRI reports were interpreted by only one author. A prospective study with several readers to allow assessment of interobserver variability would have been stronger. Second, advanced MRI techniques, such as spectroscopic MRI, diffusion-weighted, and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, were not used, although they might improve tumour assessment by providing metabolic and functional information. Finally, we used histopathological tumour maps as the source of tumour measurements. Histopathological tumour measurements are not available during clinical MRI interpretation, and further prospective studies are needed to explore how well the LPD on MRI correlates with the same measurement on pathology.

In summary, our findings help to pinpoint the limitations of MRI in detecting ECE and suggest that closer scrutiny of lesions with LPD of <3 cm on MRI might be warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Ms. Ada Muellner, BA, for editing this manuscript. Funded by: National Institutes of Health grant #R01 CA76423.

Abbreviations

- ECE

extracapsular extension

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- PZ

peripheral zone

- TZ

transition zone

- LPD

largest perpendicular (tumour) diameter

- BDDP

bi-dimensional diameter product

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jager GJ, Ruijter ET, van de Kaa CA, et al. Local staging of prostate cancer with endorectal MR imaging: correlation with histopathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:845–852. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.4.8610561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastham JA, Kattan MW, Riedel E, et al. Variations among individual surgeons in the rate of positive surgical margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. J Urol. 2003;170:2292–2295. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091100.83725.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohayda C, Kupelian PA, Levin HS, Klein EA. Extent of extracapsular extension in localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;55:382–386. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggener SE, Scardino PT, Carroll PR, et al. Focal therapy for localized prostate cancer: a critical appraisal of rationale and modalities. J Urol. 2007;178:2260–2267. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohori M, Kattan M, Scardino PT, Wheeler TM. Radical prostatectomy for carcinoma of the prostate. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:349–359. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claus FG, Hricak H, Hattery RR. Pretreatment evaluation of prostate cancer: role of MR imaging and 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiographics. 2004;24(Suppl. 1):S167–S180. doi: 10.1148/24si045516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelbrecht MR, Jager GJ, Laheij RJ, Verbeek AL, van Lier HJ, Barentsz JO. Local staging of prostate cancer using magnetic resonance imaging: a metaanalysis. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2294–2302. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graser A, Heuck A, Sommer B, et al. Per-sextant localization and staging of prostate cancer: correlation of imaging findings with whole-mount step section histopathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:84–90. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloch BN, Furman-Haran E, Helbich TH, et al. Prostate cancer: accurate determination of extracapsular extension with high-spatial-resolution dynamic contrast-enhanced and T2-weighted MR imaging - initial results. Radiology. 2007;245:176–185. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451061502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikonen S, Kivisaari L, Tervahartiala P, et al. Prostatic MR imaging. Accuracy in differentiating cancer from other prostatic disorders. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:348–354. doi: 10.1080/028418501127346972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogura K, Maekawa S, Okubo K, et al. Dynamic endorectal magnetic resonance imaging for local staging and detection of neurovascular bundle involvement of prostate cancer: correlation with histopathologic results. Urology. 2001;57:721–726. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnall MD, Imai Y, Tomaszewski J, Pollack HM, Lenkinski RE, Kressel HY. Prostate cancer: local staging with endorectal surface coil MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;178:797–802. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.3.1994421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV, Mehta SS, Carroll PR. The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2141–2149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis BJ, Pisansky TM, Wilson TM, et al. The radial distance of extraprostatic extension of prostate carcinoma: implications for prostate brachytherapy. Cancer. 1999;85:2630–2637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph T, McKenna DA, Westphalen AC, et al. Pretreatment endorectal magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging features of prostate cancer as predictors of response to external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yossepowitch O, Sircar K, Scardino PT, et al. Bladder neck involvement in pathological stage pT4 radical prostatectomy specimens is not an independent prognostic factor. J Urol. 2002;168:2011–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64284-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheeler TM, Dillioglugil O, Kattan MW, et al. Clinical and pathological significance of the level and extent of capsular invasion in clinical stage T1-2 prostate cancer. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:856–862. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Outwater EK, Petersen RO, Siegelman ES, Gomella LG, Chernesky CE, Mitchell DG. Prostate carcinoma: assessment of diagnostic criteria for capsular penetration on endorectal coil MR images. Radiology. 1994;193:333–339. doi: 10.1148/radiology.193.2.7972739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu KK, Hricak H, Alagappan R, Chernoff DM, Bacchetti P, Zaloudek CJ. Detection of extracapsular extension of prostate carcinoma with endorectal and phasedarray coil MR imaging: multivariate feature analysis. Radiology. 1997;202:697–702. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hricak H, Choyke PL, Eberhardt SC, Leibel SA, Scardino PT. Imaging prostate cancer: a multidisciplinary perspective. Radiology. 2007;243:28–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431030580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao JN, Scott AJ. A simple method for the analysis of clustered binary data. Biometrics. 1992;48:577–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hull GW, Rabbani F, Abbas F, Wheeler TM, Kattan MW, Scardino PT. Cancer control with radical prostatectomy alone in 1,000 consecutive patients. J Urol. 2002;167:528–534. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hricak H, Wang L, Wei DC, et al. The role of preoperative endorectal magnetic resonance imaging in the decision regarding whether to preserve or resect neurovascular bundles during radical retropubic prostatectomy. Cancer. 2004;100:2655–2663. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. International classification of diseases. Infirm Fr. 1981;222:26–28. (article in French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eichelberger LE, Koch MO, Eble JN, Ulbright TM, Juliar BE, Cheng L. Maximum tumor diameter is an independent predictor of prostate-specific antigen recurrence in prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:886–890. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis WJ, Chetner MP, Preston SD, Brawer MK. Diagnosis of prostatic carcinoma: the yield of serum prostate specific antigen, digital rectal examination and transrectal ultrasonography. J Urol. 1994;152:1520–1525. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]