Abstract

Disease burden within cattle is a concern around the world. Bovine borreliosis, one such disease, is caused by the spirochete Borrelia theileri transmitted by the bite of an infected Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) species tick. A number of species within the genus are capable of transmitting the agent and are found on multiple continents. Cattle in the West African nation of Mali are infested with 4 species of Rhipicephalus ticks of the subgenus Boophilus: Rhipicephalus annulatus, Rhipicephalus microplus, Rhipicephalus decoloratus, and Rhipicephalus geigyi. To date, no reports of B. theileri within Mali have been documented. We tested 184 Rhipicephalus spp. ticks by PCR that were removed from cattle at a market near Bamako, Mali. One tick, R. geigyi, was positive for B. theileri, which confirmed the presence of this spirochete in Mali.

Keywords: Bovine borreliosis, Tick, Boophilus, West Africa, Spirochete

Introduction

Borrelia theileri, the cause of bovine borreliosis, was identified in South Africa over 100 years ago and named in honor of Sir Arnold Theiler for his discovery of this spirochete (Laveran, 1903). Yet this species of spirochete is one of the least characterized pathogenic tick-borne borreliae. Historically, the spirochete has been identified from Africa, Australia, and North and South America in the peripheral blood of large domestic mammals such as cows, goats, and sheep, which are parasitized by a few ixodid tick species known to carry and transmit this bacterium (Callow, 1967; Cutler et al., 2012; Smith et al., 1978, 1985; Theiler, 1904). The clinical signs of infection in cattle and other animals are mild and variable, but usually include fever and anemia (Smith et al., 1985). No isolates of B. theileri exist, and the few attempts to grow this spirochete in vitro have failed (Smith et al., 1985). Also, minimal DNA sequence data are available to differentiate this species from other species belonging to the genus. However, from the meager amount of DNA sequences available, B. theileri groups phylogenetically with the relapsing fever spirochetes, but unlike most other members of this group, this species is transmitted by hard (ixodid) ticks rather than soft (argasid) ticks (Theiler, 1905). This spirochete infects numerous tick tissues, as demonstrated by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained organs of R. microplus (Smith et al., 1978). These one-host ticks also serve as the reservoir for B. theileri, given their efficient transovarial and transstadial transmission of the spirochete (Smith et al., 1978). Other members of this clade of relapsing fever-related spirochetes transmitted by hard ticks include Borrelia miyamotoi and Borrelia lonestari (Barbour et al., 1996; Fukunaga et al., 1995).

During our studies of tick-borne relapsing fever in Mali, we had the opportunity to collect ixodid ticks from cattle with the goal of testing them for infection with B. theileri (Schwan et al., 2012). Four Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) species of ticks infest cattle and other domestic stock in Mali: Rhipicephalus annulatus (Say), Rhipicephalus decoloratus (Koch), Rhipicephalus microplus (Canestrini), and Rhipicephalus geigyi (Aeschlimann & Morel) (Adakal et al., 2013; Smith et al., 1985; Theiler, 1905; Trees, 1978). Three of these ticks, R. annulatus, R. decoloratus, R. microplus, as well as Rhipicephalus evertsi evertsi (Neumann), are vectors of B. theileri, found in southern Africa and western Africa (Smith et al., 1985; Theiler, 1904; Trees, 1978). However, we are unaware of any reports of B. theileri within Mali or infecting the tick R. geigyi, whose role as a vector of the pathogens is uncertain (Walker et al., 2003). Therefore, our findings presented herein expand the knowledge of the distribution, tick association, and genetic characterization of B. theileri in Africa.

Materials and methods

Ticks were collected by hand from cattle on January 16 and June 19, 2010, at the Kati cattle market within the Koulikoro Region and June 20th, 2010, at the Korofina cattle market in Bamako in Mali, western Africa. Specimens were taken to the University of Bamako and tentatively identified to species based on published keys for ticks infesting domestic animals in Africa (Walker et al., 2003). The specimens were preserved in 70% ethanol and transported to the Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Montana, for further examination and testing. The ticks were removed from the ethanol and allowed to air dry. A whole tick, if less than 25 mg, or a 10–20-mg anterior section of larger ticks was placed into a microcentrifuge tube (Fisher Scientific Co, Pittsburgh, PA) and DNA extracted as previously described (Schwan et al., 2012). The mitochondrial 12S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes from selected ticks, and the Borrelia flaB, glpQ, hpt, and 16S rRNA genes were PCR-amplified and sequenced as previously reported using the primers listed in Table 1 (Schwan et al., 2012). Degenerate primers to the hpt gene were designed using Lasergene PrimerSelect (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). Sequences were aligned using ClustalW in the MEGA5 suite (http://www.megasoftware.net), and neighbor-joining trees with 1000 bootstrap replicates were produced.

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR amplification and sequencing.

| Gene | Primer name | Sequence | Expected product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 16S rRNA | T50a | GTTACGACTTCACCCTCCT | 1488 |

| FD3a | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTTAG | ||

| Rec 4a | ATGCTAGAAACTGCATGA | ||

| Rec 9a | TCGTCTGAGTCCCCATCT | ||

| 16RnaLb | CTGGCAGTGCGTCTTAAGCA | ||

| 16RnaRb | GTATTCACCGTATCATTCTGATATAC | ||

| 16S−2a | TACAGGTGCTGCATGGTTGTCG | ||

| 16S−1a | TAGAAGTTCGCCTTCGCCTCTG | ||

|

| |||

| glpQ | glpQF+1a | GGGGTTCTGTTACTGCTAGTGCCATTAC | 1002 |

| Rev−2a | CAATACTAAGACCAGTTGCTCCTCCGCC | ||

| glpQF−1a | CAATTTTAGATATGTCTTTACCTTGTTGTTTATGCC | ||

| Rev−1a | GCACAGGTAGGAATGTTGGAATTTATCCTG | ||

|

| |||

| flaB | Fla ans 5′a | TGTGATATCCTTTTAAAGAGACAAATGG | 1284 |

| Fla alt 3′a | TCTAAGCAATGACAATACATATTGAGG | ||

| flaLLb | ACATATTCAGATGCAGACAGAGGT | ||

| flaRLb | GCAATCATAGCCATTGCAGATTGT | ||

| flaLSb | AACAGCTGAAGAGCTTGGAATG | ||

| flaRSb | CTTTGATCACTTATCATTCTAATAGC | ||

|

| |||

| hpt | hptdegFc | GCAGAYATTACAAGAGARATGG | 433 |

| hptdegRc | CYTCRTCACCCCATTGAGTTCC | ||

|

| |||

| Tick 16S rRNA | Tick16S+1d | CTGCTCAATGATTTTTTAAATTGCTGTGG | 480 |

| Tick16S−1d | CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCAAGT | ||

| Tick16S+2d | TTGGGCAAGAAGACCCTATGAA | ||

| Tick16S−2d | TTACGCTGTTATCCCTAGAG | ||

| Tick16S+3d | ATACTCTAGGGATAACAGCGT | ||

| Tick16S−3d | AAATTCATAGGGTCTTCTTGTC | ||

|

| |||

| Tick 12S rRNA | SR-J-14199e | TACTATGTTACGACTTAT | 430 |

| SR-N-14594e | AAACTAGGATTAGATACCC | ||

Amplification primers in bold; all primers used for sequencing.

this study.

Results

Through morphological and sequence comparisons, we identified 2 species among the 184 Rhipicephalus adults sampled, R. geigyi and R. decoloratus. The infected tick and 20 additional specimens were selected for DNA sequence analysis, which yielded 19 R. geigyi and 2 R. decoloratus based on 100% and 99% identities of their mt 12S rRNA gene (396 and 406 bp aligned, respectively). Two representative 12S rRNA sequences for R. geigyi C7M and R. decoloratus C7F6, and the 16S rRNA sequence for R. geigyi C7M are deposited in GenBank with accession numbers KF569939, KF569940, and KF569942, respectively.

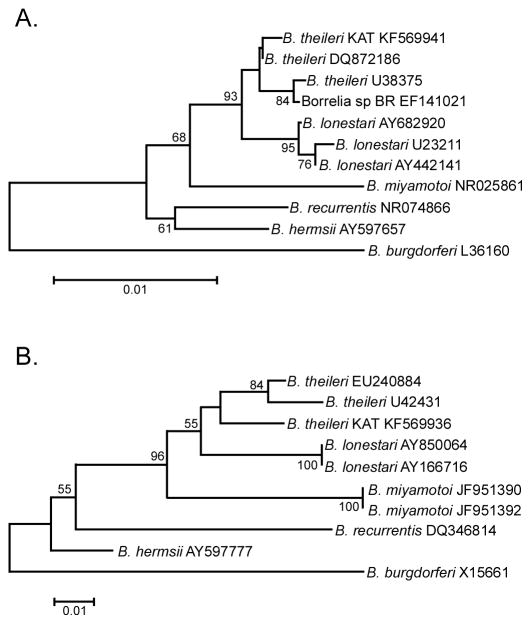

PCR amplification with borrelia-specific primers resulted in products from a single R. geigyi male (R. geigyi C7M) from the Kati market, resulting in a 0.5% infection rate. The spirochete detected is herein referred to as B. theileri KAT. Sequences were generated for B. theileri KAT, which consisted of 1271 bp of 16S rRNA, 970 bp of flaB, 365 bp of hpt, and the entire 1002-bp glpQ gene. The borrelial 16S rRNA and flaB sequences were aligned with other borrelia sequences found in GenBank (Fig. 1A and 1B, respectively). These alignments included B. theileri, B. lonestari, and B. miyamotoi, as well as Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia recurrentis, found within a soft tick and louse, respectively, and the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as the outgroup. The 16S rRNA sequence alignment grouped B. theileri KAT and Borrelia sp. BR closely with 2 B. theileri sequences from GenBank, which identified our spirochete and Borrelia sp. BR as B. theileri (Fig. 1A) (Yparraguirre et al., 2007). The B. theileri KAT flaB sequence aligned closest with other B. theileri flaB GenBank submissions, further confirming our identification (Fig. 1B). As flaB alignments with B. theileri KAT that included B. theileri from GenBank and Borrelia sp. BR resulted in minimal sequence overlap, a separate alignment compared relatedness of B. theileri KAT to Borrelia sp. BR. Similar to the 16S rRNA alignment, Borrelia sp. BR grouped closely with B. theileri KAT (data not shown). Borrelia theileri KAT glpQ and hpt genes were sequenced and submitted to GenBank (KF569938, KF569937, respectively), although no alignments were made due to a lack of comparable sequences from B. theileri elsewhere.

Fig. 1.

Phylogram comparing the Malian B. theileri KAT to other borreliae based on 16S rRNA (A) and flaB (B). Sequence lengths were trimmed to 887 bp for 16S rRNA and 226 bp for flaB to include more sequences for alignment. Trees were inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The percentage of trees (>50%) in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test of 1000 replicates are shown. Branch lengths are the number of base substitutions per site and were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA5. Taxon labels include the organism name and the GenBank accession number.

Discussion

This is the first observation of B. theileri within Mali and in R. geigyi. Rhipicephalus geigyi is genetically related to and overlaps in distribution with R. decoloratus and R. annulatus, known vectors of B. theileri. However, minimal data exist on the infection rates in B. theileri tick vectors (Estrada-Peña et al., 2006). The infection rate (0.5%) reported here is comparable to the study in Brazil which found less than 1% infected with Borrelia sp. BR in field-collected R. microplus (Yparraguirre et al., 2007). However, this sequence was not identified as B. theileri though it groups most closely with B. theileri KAT and other B. theileri in the phylogenetic analysis, leading us to conclude it is B. theileri (Fig. 1A and 1B).

Six additional R. geigyi and one R. decoloratus ticks, all female, were also collected from the same bovine as the infected R. geigyi C7M. Interestingly, none of those ticks had evidence of B. theileri infection by PCR amplification. Rhipicephalus geigyi, like all the species within the subgenus Boophilus, is a one-host tick, thus finding one infected tick upon a host suggests more may be present (Estrada-Peña et al., 2006). There are a few possible explanations for this result: (i) PCR of borrelial DNA from tick DNA extractions have lower sensitivity, likely due to inhibitory products or an overabundance of non-target DNA, leading to false negatives, (ii) R. geigyi C7M may not yet have transmitted the organism to the cow, or (iii) the prevalence of R. geigyi infected with B. theileri is below 1% and not enough ticks were sampled from the cow to find another positive.

PCR detection of the spirochete does not prove that R. geigyi is a vector for B. theileri. Borrelia can be detected in ticks that are unable to transmit the organism; its presence may be transient and cleared without colonizing the tick. More research into the competence of R. geigyi as a vector for B. theileri is needed. Tick-borne diseases of cattle are a great burden to farming communities around the world, particularly in rural Africa (Perry and Sones, 2007). Realizing the presence of B. theileri in Mali and the possible role of R. geigyi as a vector may aid in the farmers efforts to bring healthier, more valuable products to market.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. We thank Bob Fischer, Sandra Stewart, and Philip Stewart for reviewing the manuscript; Nafomon Sogoba and Sékou F. Traoré for field and administrative help; and Sory Coulibaly for allowing us to collect ticks at the cattle markets.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adakal H, Biguezoton A, Zoungrana S, Courtin F, De Clercq EM, Madder M. Alarming spread of the Asian cattle tick Rhipicephalus microplus in West Africa – another three countries are affected: Burkina Faso, Mali and Togo. Exp Appl Acarol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10493-013-9706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour AG, Maupin GO, Teltow GJ, Carter CJ, Piesman J. Identification of an uncultivable Borrelia species in the hard tick Amblyomma americanum: possible agent of a Lyme disease-like illness. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:403–409. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black WC, IV, Piesman J. Phylogeny of hard- and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10034–10038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callow LL. Observations on tick-transmitted spirochaetes of cattle in Australia and South Africa. Brit Vet J. 1967;123:492–496. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(17)39704-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S, Abdissa A, Adamu H, Tolosa T, Gashaw A. Borrelia in Ethiopian ticks. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Peña A, Bouattour A, Camicas JL, Guglielmone A, Horak I, Jongejan F, Latif A, Pegram R, Walker AR. The known distribution and ecological preferences of the tick subgenus Boophilus (Acari: Ixodidae) in Africa and Latin America. Exp Appl Acarol. 2006;38:219–235. doi: 10.1007/s10493-006-0003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga M, Takahashi Y, Tsuruta Y, Matsushita O, Ralph D, McClelland M, Nakao M. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Borrelia miyamotoi sp nov., isolated from the ixodid tick Ixodes persulcatus, the vector for Lyme disease in Japan. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:804–810. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambhampati S, Smith PT. PCR primers for the amplification of four insect mitochondrial gene fragments. Insect Mol Biol. 1995;4:233–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1995.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laveran A. Sur la spirillose des bovidés. C R Acad Sci, Paris. 1903;136:939–941. [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Sones K. Poverty reduction through animal health. Science. 2007;315(5810):333–334. doi: 10.1126/science.1138614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan TG, Anderson JM, Lopez JE, Fischer RJ, Raffel SJ, McCoy BN, Safronetz D, Sogoba N, Maiga O, Traore SF. Endemic foci of the tick-borne relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia crocidurae in Mali, West Africa, and the potential for human infection. PLOS Neglect Trop Dis. 2012;6(11):e1924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan TG, Raffel SJ, Schrumpf ME, Policastro PF, Rawlings JA, Lane RS, Breitschwerdt EB, Porcella SF. Phylogenetic analysis of the spirochetes Borrelia parkeri and Borrelia turicatae and the potential for tick-borne relapsing fever in Florida. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3851–3859. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3851-3859.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Brener J, Osorno M, Ristic M. Pathobiology of Borrelia theileri in the tropical cattle tick, Boophilus microplus. J Invertebr Pathol. 1978;32:182–190. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(78)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Miranpuri GS, Adams JH, Ahrens EH. Borrelia theileri: Isolation from ticks (Boophilus microplus) and tick-borne transmission between splenectomized calves. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:1396–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler A. Spirillosis of cattle. J Comp Pathol Ther. 1904;17:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Theiler A. Transmission and inoculability of Spirillum theileri (Laveran) Proc R Soc Lond B. 1905;76:504–506. [Google Scholar]

- Trees AJ. The transmission of Borrelia theileri by Boophilus annulatus (Say, 1821) Trop Anim Health Prod. 1978;10:93–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02235315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AR, Bouattour A, Camicas J-L, Estrada-Peña A, Horak IG, Latif AA, Pegram RG, Preston PM. A guide to identification of species. University of Edinburgh; 2003. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa; p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Yparraguirre LA, Machado-Ferreira E, Ullmann AJ, Piesman J, Zeidner NS, Soares AGC. A hard tick relapsing fever group spirochete in a Brazilian Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus. Vector Borne Zoonot Dis. 2007;7:717–721. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]