Abstract

The author describes the primary care physician’s role in caring for cancer survivors who are transitioning from oncology settings to primary care settings. Four scenarios are addressed and advantages and disadvantages of each are listed.

Larissa Nekhlyudov

Since the release of the 2006 Institute of Medicine report focusing on the transition of cancer survivors from oncology settings to primary care settings [1], there has been growing interest in assessing primary care providers’ (PCP) preparedness to care for this population of patients and mechanisms that may be used to facilitate the transition from oncology settings. Study findings have revealed that although PCPs are often willing to care for cancer survivors, their confidence and skills may be lacking [2–6]. Survivorship care plans have been proposed as a means of offering guidance to PCPs [1], educational programs have been developed [7], and medical school training programs are being launched [8, 9]. These initiatives appear well-positioned to enhance PCPs’ awareness of cancer survivorship-related issues and should be evaluated. Yet, in addition to educating PCPs and developing their competencies in caring for cancer survivors, engaging PCPs in the care of survivors may also benefit oncology providers and patients. Specifically, given that the majority of survivors are elderly and many have comorbid medical conditions [10], PCPs may prioritize and advise on the management of these conditions, promote healthy lifestyles and disease prevention, and provide psychosocial support [11]. As a result of an active interaction, PCPs may enhance the knowledge and skills of their oncology colleagues. Although data in this regard are lacking, the bidirectional contributions of oncology and PCPs may further result in enhanced quality of care and patient satisfaction as well as reduced costs. In this article, I propose models for integrating primary care in cancer survivorship programs, ranging from survivorship care “expert” PCPs to community-based PCPs without specific survivorship expertise. Although nurse practitioners and physician assistants play important roles in cancer survivorship care, the focus of this article is on primary care physicians, specifically general internists and family practitioners, and their potential contribution to the care of cancer survivors. Advantages and disadvantages for each of the models are presented in Table 1.

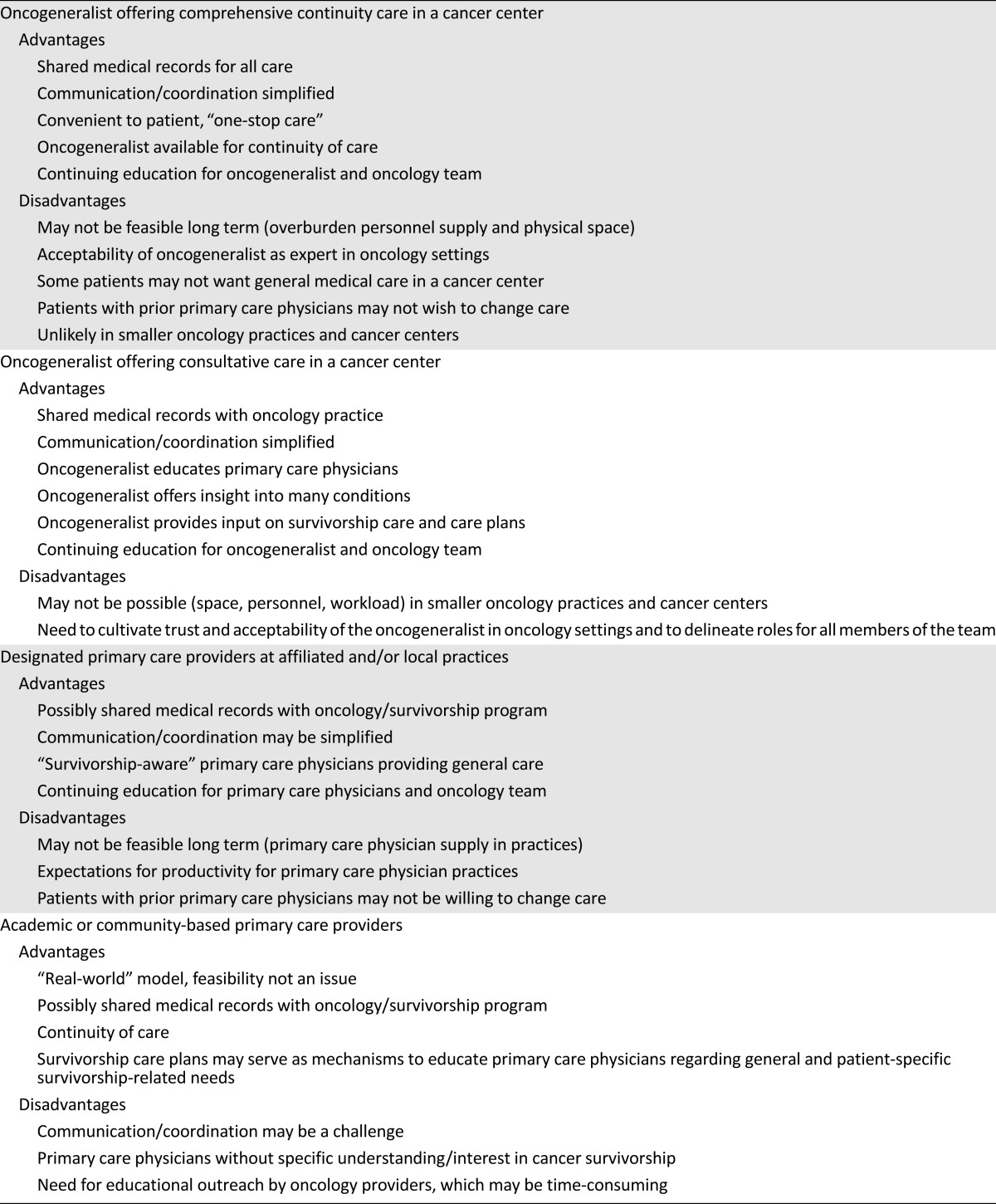

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of models of care integrating primary care into survivorship programs

The Oncogeneralist Offering Comprehensive Continuity Care in a Cancer Center

The first proposed model is for comprehensive continuity care to be provided by an oncogeneralist in a cancer center. In this model of care, the PCPs have “expertise” in cancer survivorship [12]. Because there are currently no specifically designated fellowship programs for internists, training may be acquired through educational seminars, workshops, conferences, online programs, or an internship-like “shadowing” in environments caring for cancer survivors. Existing general internal medicine fellowship programs (such as the National Research Service Award, supported by the National Institutes of Health) may also serve as mechanisms to train physicians in survivorship care with a focus on research and/or educational scholarship. The training has to provide PCPs with an in-depth understanding of the implications of cancer and/or its treatment on patients’ health care needs, including surveillance for recurrences and monitoring for and management of late effects, as well as psychosocial sequelae. Once trained, the “oncogeneralist” becomes a member of a cancer survivorship program as a practicing clinician at a cancer facility and offers comprehensive and complementary care, along with the cancer team, to cancer patients during and following treatment. The oncogeneralist is closely linked to the oncology clinicians, actively participates in team-based educational programs, such as tumor boards and case reviews, and, if possible, shares clinic space. This model provides a continuous process for educational growth for internists and oncologists. Together with the oncology team, the oncogeneralist participates in the development of a survivorship care plan individualized to patient needs, particularly weighing in on the interplay between cancer-related and comorbid medical conditions and their treatments. If feasible within the setting, the oncogeneralist can take on the role of PCP for patients, with the expectation of providing them with long-term continuity of care including cancer-related surveillance, comorbid disease management, disease prevention, and health promotion, as well as psychosocial care.

The Oncogeneralist Offering Consultative Care in a Cancer Center

The second model also includes an expert PCP with training in comprehensive survivorship care. However, unlike the example above, the oncogeneralist serves as a consultant rather than a continuity-of-care provider. In this model, the oncogeneralist does not follow patients long term, but offers only consultative services (or visits). Such visits may occur during treatment, for example, in a patient with comorbid medical conditions (such as hypertension or diabetes) who is undergoing potentially cardiotoxic chemotherapy treatment. In this capacity, the oncogeneralist evaluates and prioritizes the management of the medical condition(s) and potentially reduces the need to refer the patient to a specialist. Furthermore, by having basic oncology expertise, the oncogeneralist is better equipped to manage the effects of treatment than a nontrained PCP. If additional expertise is needed, the patient may be referred to a specialist, with communication maintained with the oncogeneralist. As part of the consultative model, the oncogeneralist communicates with the oncology clinician, the patient’s PCP, and the patient. Although an oncogeneralist may be involved during active treatment, the more practical scenario is for the oncogeneralist to play a consultative role as patients complete treatment and transition to the survivorship phase of care. In this role, the oncogeneralist works with the oncology team to complete a survivorship care plan, offering insights into comorbid medical condition monitoring and management, disease prevention, and health promotion, as well psychosocial care. Once a care plan is developed, the oncogeneralist communicates with the patient’s PCP, allowing for a smooth transition of care. Lastly, the oncogeneralist may be available on a consultative basis for patients during the long-term survivorship phase of care.

Designated Primary Care Providers at Affiliated and/or Local Practices

In the third proposed model of care, a cancer facility identifies PCPs who have expressed an interest (without specified expertise) in caring for survivors. These providers may be practicing in settings that are formally affiliated with the cancer center, or they may be practicing in the surrounding neighborhoods. These designated PCPs care for the general population, but have a panel of patients with prior history of cancer and are interested in caring for this population. Although they may not have expertise in survivorship, they have participated in educational programs (i.e., continuing medical education) or informal training in issues related to cancer surveillance, monitoring for late effects, and psychosocial needs. Thus, when transitioning from active care, patients may be offered an opportunity to choose such a PCP in their community. Survivorship care plans are created by the oncology team and communicated to the PCP. Bidirectional communication and education occur as the teams develop ongoing relationships, a process that enhances the transition of subsequent patients. Together, they provide shared care for the patient, and if and when deemed appropriate, the PCP takes over all aspects of care.

Academic and/or Community-Based Primary Care Providers

The fourth proposed model of survivorship care occurs in the setting of academic or community-based primary care facilities. This model of care is the most likely scenario for survivorship care as most survivors are cared for in settings that may not permit development of the previously described examples. PCPs in this model are either academic- or community-based providers who have no training, expertise, and likely no predefined interest in cancer survivorship care. These providers can be engaged in the care of patients during cancer treatment and following completion of treatment. Bidirectional communication with the oncology team can occur by telephone and/or electronic means. There are numerous cancer types and treatments, with ever-evolving available modalities. Evidence regarding surveillance for recurrences and late effects is growing. As such, it is not feasible to train practicing PCPs to be knowledgeable across the spectrum of cancer survivorship care. PCPs may be overwhelmed and may not have the interest to take on additional tasks. Survivorship care plans may serve as mechanisms to educate PCPs regarding general cancer survivorship-related needs as well as those that are patient-specific. The plans, developed in oncology settings, must be shared with PCPs and their patients; however, communication between the oncology team and the PCP must entail more than a document. Establishing relationships is important as PCPs can answer questions regarding management of comorbid medical conditions, assume a primary role in managing certain aspects of care, and provide continuity that is critical during and following completion of treatment. In order to maximize the benefits of this model, oncologists should specifically reach out to PCPs to provide ongoing education about cancer-related surveillance and monitoring. This may occur via informal communication in consultation letters and updated survivorship care plans, but formal in-person or web-based seminars may be more advantageous for both educational and interpersonal development.

Conclusion

The growing population of cancer survivors requires comprehensive management of their cancer and noncancer-related needs and thus would benefit from active involvement of primary care providers. This article has proposed models for integrating primary care into cancer survivorship programs and has outlined the advantages and disadvantages for each of the models. This article adds to the literature by focusing specifically on the integration of primary care in survivorship programs and the potential implications of this collaborative approach in both academic and community-based settings. Evaluation of innovative models of cancer survivorship care is needed.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Don S. Dizon, Daphne Suzin, Susanne McIlvenna. Sexual Health as a Survivorship Issue for Female Cancer Survivors. The Oncologist 2014;19:202–210.

Implications for Practice: Sexual health is an important aspect of life and an area of concern consistently identified by women after treatment for cancer. Discussing sexual health should become a routine part of conversations with patients before, during, and especially after cancer treatment. Suggestions for communication and an overview of endocrine and nonendocrine treatment options are provided. Resources for patients and providers and the importance of working in a multidisciplinary way, whether it be with another clinician or a sexual health expert, to help patients with sexual health concerns is important as we seek to improve the sexual health of female cancer survivors.

Disclosures

The author indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies . From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, et al. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3338–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer DK, Gerstel A, Leak AN, et al. Patient and provider preferences for survivorship care plans. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e80–e86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Stricker CT, et al. Delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: The perspective of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:933–938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudson SV, Miller SM, Hemler J et al. Adult cancer survivors discuss follow-up in primary care: “Not what I want, but maybe what I need.” Am Fam Med 2012;10:418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cowens-Alvarado R, Sharpe K, Pratt-Chapman M, et al. Advancing survivorship care through the National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center: Developing American Cancer Society guidelines for primary care providers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:147–150. doi: 10.3322/caac.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uijtdehaage S, Hauer KE, Stuber M, et al. Preparedness for caring of cancer survivors: A multi-institutional study of medical students and oncology fellows. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24:28–32. doi: 10.1080/08858190802665260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uijtdehaage S, Hauer KE, Stuber M, et al. A framework for developing, implementing, and evaluating a cancer survivorship curriculum for medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):491–494. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2012;62:220–241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Klabunde CN, Ambs A, Keating NL, et al. The role of primary care physicians in cancer care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1029–1036. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1058-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong S, Nekhlyudov L, Didwania A, et al. Cancer survivorship care: Exploring the role of the general internist. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):495–500. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]