To determine the clinical impact of extensive genetic analysis, the use of a targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform (FoundationOne) in advanced cancer patients was reviewed. Mutational profiling using a targeted NGS panel identified potentially actionable alterations in a majority of the patients. The assay identified additional therapeutic options and facilitated clinical trial enrollment. As time progresses, NGS results will be used to guide therapy in an increasing proportion of patients.

Keywords: Next-generation sequencing, Genotype, Precision medicine, Molecular targeted therapy, Cancer, Mutation

Abstract

Background.

Oncogenic genetic alterations “drive” neoplastic cell proliferation. Small molecule inhibitors and antibodies are being developed that target an increasing number of these altered gene products. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a powerful tool to identify tumor-specific genetic changes. To determine the clinical impact of extensive genetic analysis, we reviewed our experience using a targeted NGS platform (FoundationOne) in advanced cancer patients.

Patients and Methods.

We retrospectively assessed demographics, NGS results, and therapies received for patients undergoing targeted NGS (exonic sequencing of 236 genes and selective intronic sequencing from 19 genes) between April 2012 and August 2013. Coprimary endpoints were the percentage of patients with targeted therapy options uncovered by mutational profiling and the percentage who received genotype-directed therapy.

Results.

Samples from 103 patients were tested, most frequently breast carcinoma (26%), head and neck cancers (23%), and melanoma (10%). Most patients (83%) were found to harbor potentially actionable genetic alterations, involving cell-cycle regulation (44%), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT (31%), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (19%) pathways. With median follow-up of 4.1 months, 21% received genotype-directed treatments, most in clinical trials (61%), leading to significant benefit in several cases. The most common reasons for not receiving genotype-directed therapy were selection of standard therapy (35%) and clinical deterioration (13%).

Conclusion.

Mutational profiling using a targeted NGS panel identified potentially actionable alterations in a majority of advanced cancer patients. The assay identified additional therapeutic options and facilitated clinical trial enrollment. As time progresses, NGS results will be used to guide therapy in an increasing proportion of patients.

Implications for Practice:

Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) identifies genetic alterations that may confer sensitivity to approved and experimental targeted therapies in advanced cancer. The authors reviewed their experience with a targeted NGS assay and identified potentially actionable genetic alterations in 83% of tumors, with 21% of these patients receiving genotype-directed therapy. This study highlights the promise of targeted NGS for identifying actionable genetic alterations, facilitating clinical trial enrollment.

Introduction

Cancer is a disease initiated, propagated, and maintained by somatic genetic events. Advances in sequencing technology have facilitated the identification of crucial genetic alterations that “drive” cancer cell growth by constitutive activation of cell signaling/cell cycling pathways or by inactivation of critical negative regulators of these networks [1–5]. Recently, a number of small molecule inhibitors and antibodies have been developed that target particular oncogenic drivers [6–10]. These targeted agents may be equivalent or even inferior to standard therapy in an unselected population but frequently induce dramatic regression in tumors harboring the target, demonstrating the value of “precision” medicine [11–13]. Despite notable successes, effective genetically targeted therapies currently remain unavailable for most patients.

Imperative to exploiting the molecular vulnerabilities of cancer is the ability to identify potentially actionable genetic alterations (defined in Table 1). Currently, the most common clinically used sequencing platforms assess a limited number of hotspot mutations in one or greater frequently altered genes (i.e., Cobas testing for BRAF V600E mutations in melanoma) [14–16]. These approaches may uncover the most extensively validated mutations in several tumor types. However, it is becoming increasingly evident that more extensive analysis of a tumor’s genetic landscape is critical in at least the following scenarios. First, driver genes contain activating mutations at non-hotspot locations that confer sensitivity to approved therapies (i.e., BRAF L597 mutations in melanoma) [17, 18]. Second, crucial alterations that are more prevalent in one malignancy may also predict response to available agents in a distinct tumor type (i.e., BRAF V600E mutation in melanoma and lung cancer) [19]. Third, clinically relevant gene fusions are not detected with hotspot testing methods [20]. Finally, and most importantly, numerous clinical trials involving experimental targeted agents are being conducted. Many agents are now demonstrating signs of efficacy, even in previously recalcitrant gene pathways involving activated RAS, impaired p53, and loss of cyclin-dependent kinase regulation [21–24]. A significant proportion of patients may therefore be excluded from potentially effective therapeutics based on incomplete genetic profiling.

Table 1.

Definitiona and classification of potentially actionable alterations

At our center, we have used a hotspot-based sequencing platform (SNaPshot) in selected tumor types but are currently transitioning to targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) in many cases. The particular commercially available assay (FoundationOne, Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA, http://www.foundationmedicine.com) sequences the entire coding regions of 236 genes with clinical or preclinical relevance in cancer and 47 introns in 19 frequently rearranged genes and has been extensively described and validated [25, 26]. This approach provides more comprehensive genetic characterization of malignancies and frequently identifies potentially actionable mutations [25]. However, the actual implications of such an approach in clinical practice have not been well described.

In this study, we reviewed our experience with FoundationOne at Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) for the first 103 patients undergoing sequencing. Our primary interest was determining whether this tumor profiling identified actionable or potentially actionable genetic alterations (hereafter aggregated as “potentially actionable alterations”) and subsequently influenced treatment selection. We classified these genetic alterations based on whether agents were approved or experimental (Table 1). Secondary goals included assessing the spectrum of potentially actionable alterations identified across malignancies and the demographics of patients tested.

Methods

Study Subjects/Design

After institutional review board approval was obtained, we retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records from VICC for patients who met inclusion criteria. Patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of malignancy were included in this study if the targeted NGS assay was performed on their tumor tissue between April 1, 2012 and August 30, 2013. No restrictions of tumor histology, disease stage, subsequent or previous treatment, performance status, or other factors were imposed. The decision to obtain the NGS assay for a particular patient was implemented solely at the discretion of the primary clinician, in general for patients with refractory disease and limited treatment options, rare tumors, or clinical trial eligibility investigation. Testing was obtained to inform subsequent therapeutic options and was performed for strictly clinical indications.

One hundred three malignant tumors from patients seen at VICC were assessed (101 solid tumors and 2 hematologic malignancies). Tissue acquired by core needle biopsies, excisional biopsies, or surgical resection (or peripheral blood in the single case of leukemia) could undergo sequencing. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples, stored as either tissue blocks or in unstained slides were procured by the testing facility (Foundation Medicine) from the pathology departments at VICC or outside facilities. A total tumor volume of ≥1 mm3 with ≥80% cellularity (or ≥30,000 cells) and tumor content (ratio of malignant to nonmalignant cells) of ≥20% were required. Samples without evaluable results (because of low tumor content or other technical considerations) were not considered. In most of these cases, additional samples were analyzed, and evaluable results were obtained.

There were two coprimary endpoints for this study. First, we assessed the percentage of patients with additional therapy options uncovered by detecting potentially actionable genetic alterations. Second, we evaluated the percentage of patients who actually received genotype-directed therapy. Genetic alterations were defined as actionable if they were associated with (or potentially associated with) susceptibility to an approved therapy or experimental agent (being tested at any location in the U.S.). Additionally, we considered whether an alteration was actionable based on the timing of the report. For example, if a clinical trial (either nationally or at our institution) targeting a particular mutation subsequently opened after the report was obtained, it was not included in our criteria. Patients were classified as having receiving genotype-directed therapy if they received an experimental or approved agent based on their genetic testing results.

Genetic Testing

Targeted next-generation sequencing was performed by Foundation Medicine in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment-certified laboratory. The targeted NGS platform (FoundationOne) has been previously described and validated [25] and is described briefly here. After the assay was ordered by the treating physician, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue was obtained. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained slides were reviewed and verified for tumor content by pathologists at Foundation Medicine, and DNA was extracted from adjacent unstained FFPE tissue. Double-stranded DNA was subsequently quantified, fragmented, and purified. Library construction was then performed, followed by DNA amplification. Solution hybridization then targeted 4,557 exons of 236 cancer-related genes and 47 introns of 19 genes commonly rearranged in cancer (gene list provided in supplemental online Table 1). Sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, http://www.illumina.com). Sequence reads then were mapped to the human genome and compared with known databases such as COSMIC [27].

Reporting and Annotation of Genetic Testing Results

The final report that the clinician receives includes detected mutations, amplifications, homozygous deletions, and translocations in the sequenced regions. The criteria for inclusion of genetic alterations in the final report available to the clinician have been described previously [25] and are briefly summarized here. For base substitution, final calls were made at a mutant allele frequency (MAF) of ≥5% or ≥1% for known mutation hotspots after filtering for read location bias and strand bias. For copy number alterations (CNA), focal amplifications were called at ≥6 copies and homozygous deletions were called at 0 copies. Gene fusions were detected by assessing chimeric read pairs, and the function of the rearrangements was predicted. Because the final report that the clinician uses to make clinical decisions does not contain MAF or CNA data at this time, this information was not included in this study. Additionally, variants of uncertain significance have recently been added to the clinician’s report generated by Foundation Medicine but are not discussed in this study.

Statistical Considerations

No formal statistical hypotheses were assessed; analyses were descriptive in nature. The sample size was determined by the available patients with genetic testing information. All descriptive analysis was performed using frequencies and percentiles. The medians and ranges were reported for continuous variables. Demographic and genetic characteristics were not compared between groups (such as by tumor histology) because of multiple categories with low patient numbers per group. Median follow-up time subsequent to obtaining genetic information was calculated by the method of Kaplan and Meier. Analyses were performed with SPSS version 22 (SPSS software, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, http://www-01.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss).

Results

Patient Characteristics

One hundred three patient tumor samples were sequenced with the NGS assay during the study period. A wide variety of tumor histologies were analyzed (Table 2; histologic subtypes assessed listed in supplemental online Table 2). The most common tumor evaluated was breast adenocarcinoma (particularly triple negative breast cancer) followed by tumors arising in the head and neck (including squamous cell carcinomas, salivary gland tumors, and thyroid carcinomas). Melanomas, sarcomas, and lung carcinomas were the next most frequent types of cancer assessed.

Table 2.

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics

Baseline demographics for patients tested are displayed in Table 2. The median age was 53 years with 66% being females. The majority of patients had stage IV malignancy (85%) with the remainder having stage III disease (either unresectable or resected at high risk of recurrence). Many patients were heavily pretreated with up to eight previous therapies. However, the median number of prior therapies was one, because a large number of patients underwent sequencing near the time of initial diagnosis. Patients generally had good performance status, with 82% reported to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–1 at the time of testing. Prior to targeted NGS, limited genetic testing had been performed on seven tumor samples and had been found to harbor a potentially actionable mutation; subsequent testing was performed to identify additional actionable alterations upon the onset of acquired resistance. In addition, all breast carcinomas were subjected to HER2 expression testing by immunohistochemistry prior to sequencing.

Genetic Alterations Detected

At least one genetic alteration was identified in 97 tumor samples (94%) with a median of three alterations detected per tumor (Table 3). Potentially actionable mutations (defined in the Introduction) were identified in 86 patients (83%) with a median number of two actionable mutations per patient. Most samples harbored either one or two actionable mutations (n = 25 and 26, respectively), although three or greater potentially actionable genetic alterations were detected in 34 biopsied tumor specimens. Actionable alterations were identified throughout tumor types, including in 100% of breast carcinomas and melanomas (and in all of the gastrointestinal and hematologic malignancies in very small numbers; supplemental online Fig. 1). Renal carcinomas were the least likely to harbor actionable mutations (33%), although only six tumors were analyzed, including a variety of histologic subtypes. Also notably, six tumors harbored no identified mutations (actionable or otherwise) consisting of the following tumor types: two adenoid cystic carcinomas, salivary gland adenocarcinoma, lung large cell neuroendocrine tumor, soft tissue granular cell tumor, and Merkel cell carcinoma.

Table 3.

Testing results

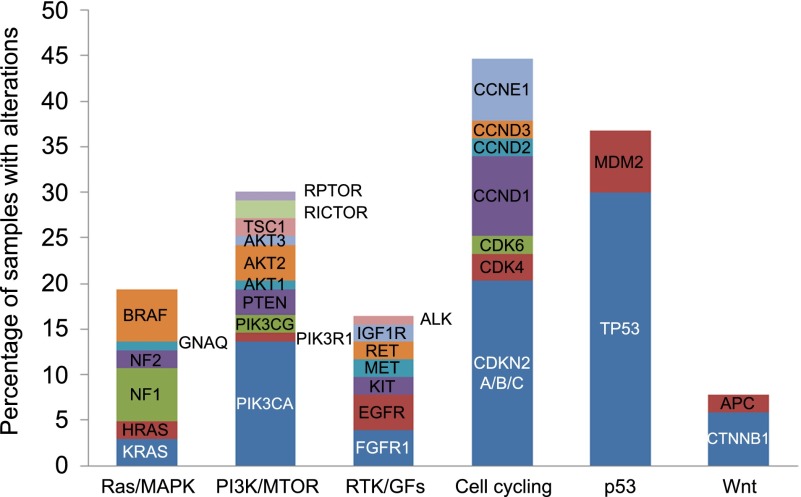

Genetic alterations were detected across a range of functionally relevant pathways (Fig. 1). Cell cycle-associated genes were the most frequently dysregulated pathways with mutations, amplifications, or deletions present in 44% of tumors. Mutations in TP53 comprised the most frequently identified alteration in any single gene, found in 32% of tested malignancies. Alterations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT pathways were also identified in a large proportion of samples.

Figure 1.

Spectrum of potentially actionable genetic alterations across tumor types, including mutations, amplifications, homozygous deletions, and fusions.

Abbreviations: GF, growth factor; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase.

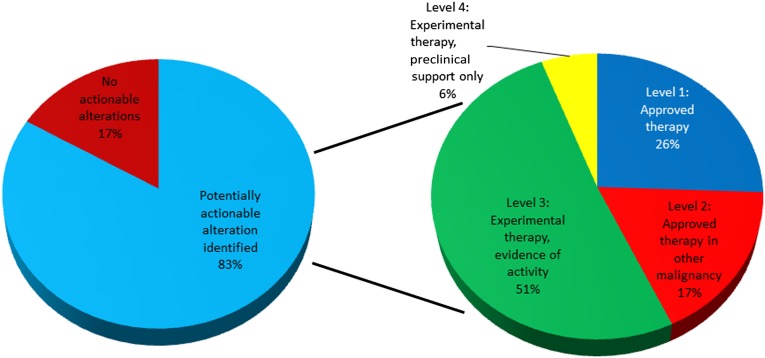

Treatment Options and Genetic Testing

We then assessed whether genetic testing impacted the possible treatment options for patients undergoing NGS analysis. Of the 103 patients assessed, 86 (83%) were found to have potentially actionable genetic alterations in their tumors. Twenty-six percent of these patients (22 patients) had alterations that predicted sensitivity to targeted agents already approved for the tumor type assessed (Fig. 2). An additional 17% of tumors harbored alterations that could be targeted by agents approved for another cancer type. Furthermore, 51% were potential candidates for genotype-directed therapy in clinical trials that have demonstrated at least early activity in the clinical setting. The remaining 6% were eligible for clinical trials with only preclinical rationale for their use.

Figure 2.

Potential genotype-directed therapeutic options available based on genetic profiling.

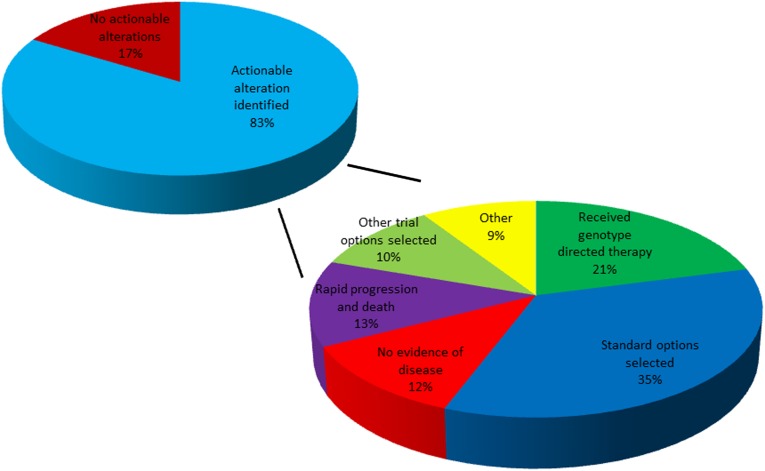

Treatment Assignments and Genetic Testing

Next, we evaluated whether the information gained from the NGS analysis informed treatment decisions (Fig. 3). This assay was initially used beginning in April of 2012; patients had a median follow up time of 4.1 months. A total of 18 patients received genotype-directed therapy (21% of those with actionable genetic alterations). Of patients who were treated with genotype-directed therapy, 7 received clinically available agents, and 11 were enrolled in clinical trials. The most common reasons for not offering targeted therapy included selection of standard treatment options during the study timeframe (35%), no evidence of disease (NED) following surgical resection or systemic therapy (12%), rapid progression and death without further treatment (13%), and enrollment in other, non-genotype-based clinical trials (10%). Notably, patients who received standard therapy did so at their treating clinicians’ discretion for a variety of reasons including continued response to an agent started before testing, other available agents judged to be more attractive than targeted therapy, or inability to travel to a clinical trial. Patients with NED had completely resected stage III/IV tumors with high risk of recurrence and underwent testing in case systemic therapy was later required (with one exception of a patient who had a complete response to systemic therapy). Patients received genetically targeted therapy in most tumor types (supplemental online Fig. 1). We did not consider therapy given in response to other standard tests as genotype-directed therapy (i.e., trastuzumab given in HER2-amplified breast cancer that had already been classified as HER2/neu amplified by other testing methods).

Figure 3.

Outcome and therapy assignment following genetic profiling.

Notable treatment responses were observed in several patients (targeted therapy assignments listed in supplemental online Table 3). One patient with refractory T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia with disease progression through five different lines of standard therapy was found to harbor a JAK1 mutation and was treated with ruxolitinib (a JAK1/2 inhibitor). She experienced improvement in her white blood cell counts (>50%) with decreased transfusion requirements for 5 months. An additional patient with melanoma complicated by refractory ascites was found to have a BRAF V600E mutation not identified by previous testing methods, most likely because of low allele frequency. She was started on dabrafenib with a dramatic durable improvement in her symptoms and tumor burden. An EML4-ALK fusion was identified in a patient with metastatic mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the lung. She was subsequently treated with crizotinib and experienced an early response with ongoing therapy. Notably, based on these testing results, histologic reassessment revealed this tumor to be more likely an adenocarcinoma.

Additional Findings

Several additional findings may have implications for future clinical trial design and for discovery of novel genetic alterations. For example, a patient with melanoma was found to harbor a BRAF rearrangement. Further experiments identified this as a PAPSS1-BRAF fusion, a novel finding in melanoma. In vitro testing identified that this fusion product constitutively activated the MAPK signaling, which was highly sensitive to MEK inhibition [28]. Although this finding did not benefit this individual patient, who unfortunately progressed rapidly and died, a clinical trial targeting BRAF fusions and other BRAF non-V600 alterations with trametinib is now in advanced planning stages. Additionally, the prevalence of particular mutations across tumor types, notably genes involved in cell-cycle regulation, may inform future trial design targeting cyclin-dependent kinases.

Discussion

In this study, we report our single-institution experience over a 17-month period implementing a targeted NGS assay in 103 advanced cancer patients. With a short median time of follow-up (4.1 months), the majority of patients (83%) had additional treatment options based on their genetic testing with targeted NGS. Many with potentially actionable mutations actually went on to receive genotype-directed therapy (21%), mostly in clinical trials. Of this group, several patients with heavily pretreated, refractory disease without available standard therapy experienced impressive responses from molecularly targeted agents. More patients could have received genotype-directed therapy, but some potentially available clinical trials were open in very few locations nationwide (for example, agents targeting inactivated p53), practically limiting patient enrollment. As trials assessing targeted agents continue to proliferate nationally, the number in studies will most likely further increase.

Molecular tumor profiling is becoming increasingly important in the management of patients with advanced cancer. Currently, a variety of molecular diagnostic platforms are available [29]. Hotspot-based assays are most commonly used in clinical practice. These range from polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays of a single point mutation (for example BRAF V600E mutation testing in melanoma) to more extensive PCR- or mass spectrometry-based platforms assessing multiple point mutations across several genes (such as SNaPshot or Sequenom) [14, 16]. On the other end of the spectrum, whole genome and whole exome sequencing (WGS/WES) are now feasible, primarily in research settings. Practical considerations related to data analysis, cost, and delay have constrained the widespread use of WGS/WES in clinics [30]. By contrast, targeted NGS sequences the entire coding region of a large number of preselected genes with clinical or preclinical relevance in cancer [31]. Although less comprehensive than WGS/WES, targeted NGS does provide a comprehensive analysis of genes with potential therapeutic and prognostic importance, a quick turnaround time (2–3 weeks in this case), and a standardized analytics pipeline [25]. Whichever method clinicians choose, they should carefully consider and account for turnaround time (as well as possible referral/screening delays if a clinical trial option is pursued) and the possibility of inadequate sample for analysis when counseling patients.

Given our experience, we believe that a targeted NGS approach has potential value in several ways. First, additional potentially active therapies can be identified, enabling clinical trial enrollment for patients without available treatment options and pinpointing trials for patients likely to benefit. Conversely, even “negative” sequencing information may be clinically useful to direct patients toward non-genotype-directed clinical trials (i.e., immunotherapy, chemotherapy) or even no additional treatment. Second, novel genetic findings can be found (e.g., a BRAF fusion in melanoma), which leads to preclinical studies and new clinical trials. Third, targeted NGS can help define prognostic and pathologic characteristics of molecular cohorts within and across tumor types, facilitating the development of so-called “basket” trials, which enroll based on particular mutations regardless of tumor histology. Finally, targeted NGS sequencing could be used as an initial sequencing strategy to investigate unexpected responses in clinical trials for both clinical and/or research purposes, analogous to previously published approaches with WGS [32].

Many unanswered questions remain regarding implementation of these technologies. First, in our study, some patients with potentially actionable alterations did not respond to genotype-directed therapy, highlighting our still underdeveloped understanding of the pathophysiologic implications of many genetic alterations. In this context, we strongly encourage oncologists to treat patients with potentially actionable mutations of unclear significance in the context of a clinical trial. Second, the most appropriate indications for obtaining targeted NGS are not yet clear. At our institution, the approach varies by provider, but we generally consider FoundationOne testing for patients with metastatic/unresectable cancer who are candidates for systemic therapy, with at least one of the following indications: (a) no institutional cancer-specific genetic testing panel exists for that particular tumor; (b) prior genetic testing did not identify an actionable mutation; (c) minimal or no standard therapy options are available; or (d) clinical trial eligibility testing. However, we cannot broadly define which tumors should or should not be subjected to targeted NGS. Third, randomized studies in the future will need to assess whether targeted NGS improves overall outcomes (similar to the approach by Von Hoff et al. [33]). We did not attempt any comparisons in our study because of small numbers receiving targeted therapy (n = 18), lack of evaluable responses in some patients (because of recent therapy initiation or treatment at an outside facility), and heterogeneous malignancies (including one leukemia). Finally, financial constraints must also be considered in this evolving field. Thoughtful and data-driven assessments will be critical to balance testing costs, therapeutic benefit, and potentially, avoidance of ineffective, costly targeted agents that are likely to be ineffective.

There are several limitations to this study. Samples over a wide variety of malignancies were sequenced (and included rare tumor types). Results and treatment assignments were evaluated in a retrospective fashion. Both of these factors may limit generalizability to other cohorts of patients (as above). Additionally, the concept of an “actionable mutation” is a moving target. The level of evidence for targeting alterations identified in this experience will change in the coming years as experimental agents move through the developmental pipeline. Further, in several tumors (i.e., breast, lung, melanoma), analysis was largely limited to tumors previously determined to lack actionable mutations based on less comprehensive testing (e.g., melanomas tested only for BRAF, NRAS, KIT, GNA11, and GNAQ mutations), which limits generalizability. In addition, we did not consider tumors without evaluable results (from low tumor content, etc., previously shown in <5% of cases) [25]; this would potentially decrease the percentage of tumors with actionable mutations. Finally, many tumors tested harbored more than one potentially actionable mutation, but few treatment algorithms exist to stratify treatment options in these cases. Despite these limitations, identification of actionable genetic alterations is likely to become increasingly clinically routine as targeted agents proliferate.

Conclusion

Our experience with targeted NGS in a group of advanced cancer patients identified potentially targetable genetic alterations in the majority of patients across tumor types. This information uncovered additional, genotype-directed treatment options for patients, with several patients receiving clinical benefits from targeted therapy. As molecularly targeted therapeutic agents with increasing clinical efficacy are developed targeting a variety of cell signaling pathways, comprehensive genetic profiling with targeted NGS will likely continue to increase in importance.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant K12 CA 0906525 (to D.B.J. and C.M.L.). Additionally, the authors thank the Joyce Family Foundation, the Martell Foundation, the Kleburg Foundation, and the Bradford Family Foundation.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Douglas B. Johnson, Kimberly B. Dahlman, Jared Knol, Igor Puzanov, Justin M. Balko, Carlos L. Arteaga, Jeffrey A. Sosman, William Pao

Provision of study materials or patients: Jill Gilbert, Igor Puzanov, Julie Means-Powell, Barbara A. Murphy, Laura W. Goff, Vandana G. Abramson, Marta A. Crispens, Ingrid A. Mayer, Jordan D. Berlin, Leora Horn, Vicki L. Keedy, Nishitha M. Reddy, Carlos L. Arteaga, Jeffrey A. Sosman

Collection and/or assembly of data: Douglas B. Johnson, Kimberly H. Dahlman, Jared Knol, William Pao

Data analysis and interpretation: Douglas B. Johnson, Kimberly H. Dahlman, Jared Knol, Justin M. Balko, Christine M. Lovly, Laura W. Goff, Nishitha M. Reddy, Carlos L. Arteaga, Jeffrey A. Sosman, William Pao

Manuscript writing: Douglas B. Johnson, Christine M. Lovly, Jeffrey A. Sosman, William Pao

Final approval of manuscript: Douglas B. Johnson, Kimberly H. Dahlman, Jill Gilbert, Igor Puzanov, Julie Means-Powell, Justin M. Balko, Christine M. Lovly, Barbara A. Murphy, Laura W. Goff, Vandana G. Abramson, Marta A. Crispens, Ingrid A. Mayer, Jordan D. Berlin, Leora Horn, Vicki L. Keedy, Nishitha M. Reddy, Carlos L. Arteaga, Jeffrey A. Sosman, William Pao

Disclosures

Christine M. Lovly: Pfizer (C/A); Qiagen (H); Leora Horn: Bristol Myers Squibb, Helix Bio, PUMA (unpaid) (C/A); Astellas (RF); Other: Boehringer Ingelheim; Vicki L. Keedy: Ziopharm (C/A); Ziopharm, Merrimack, Pfizer, J&J/Jansenn, Threshold (RF); Nishitha M. Reddy: Celgene, Immunogen (C/A); William Pao: MolecularMD (IP). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: A review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–566. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakahara M, Isozaki K, Hirota S, et al. A novel gain-of-function mutation of c-kit gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1090–1095. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine AJ, Oren M. The first 30 years of p53: Growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749–758. doi: 10.1038/nrc2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovly CM, Dahlman KB, Fohn LE, et al. Routine multiplex mutational profiling of melanomas enables enrollment in genotype-driven therapeutic trials. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dias-Santagata D, Akhavanfard S, David SS, et al. Rapid targeted mutational analysis of human tumours: A clinical platform to guide personalized cancer medicine EMBO Mol Med 20102146–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halait H, Demartin K, Shah S, et al. Analytical performance of a real-time PCR-based assay for v600 mutations in the braf gene, used as the companion diagnostic test for the novel braf inhibitor vemurafenib in metastatic melanoma Diagn Mol Pathol 2012211–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahadoran P, Allegra M, Le Duff F, et al. Major clinical response to a braf inhibitor in a patient with a braf l597r-mutated melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e324–e326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahlman KB, Xia J, Hutchinson K, et al. Braf l597 mutations in melanoma are associated with sensitivity to mek inhibitors Cancer Discov 20122791–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters S, Michielin O, Zimmermann S. Dramatic response induced by vemurafenib in a BRAF V600E-mutated lung adenocarcinoma J Clin Oncol 201331e341–e344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drilon A, Wang L, Hasanovic A, et al. Response to cabozantinib in patients with ret fusion-positive lung adenocarcinomas Cancer Discov 20133630–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ascierto PA, Schadendorf D, Berking C, et al. MEK162 for patients with advanced melanoma harbouring NRAS or Val600 BRAF mutations: A non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:249–256. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jänne PA, Shaw AT, Pereira JR, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:38–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehmann S, Bykov VJ, Ali D, et al. Targeting p53 in vivo: A first-in-human study with p53-targeting compound apr-246 in refractory hematologic malignancies and prostate cancer J Clin Oncol 2012303633–3639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickson MA, Tap WD, Keohan ML, et al. Phase II trial of the cdk4 inhibitor pd0332991 in patients with advanced cdk4-amplified well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma J Clin Oncol 2013312024–2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1023–1031. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med. 2012;18:382–384. doi: 10.1038/nm.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepherd R, Forbes SA, Beare D, et al. Data mining using the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer biomart. Database (Oxford) 2011;2011:bar018. doi: 10.1093/database/bar018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutchinson KE, Lipson D, Stephens PJ, et al. Braf fusions define a distinct molecular subset of melanomas with potential sensitivity to mek inhibition Clin Cancer Res 2013196696–6702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meador CB, Micheel CM, Levy MA et al. Beyond histology: Translating tumor genotypes into clinically effective targeted therapies. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ulahannan D, Kovac MB, Mulholland PJ, et al. Technical and implementation issues in using next-generation sequencing of cancers in clinical practice. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:827–835. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagle N, Berger MF, Davis MJ, et al. High-throughput detection of actionable genomic alterations in clinical tumor samples by targeted, massively parallel sequencing Cancer Discov 2012282–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iyer G, Hanrahan AJ, Milowsky MI, et al. Genome sequencing identifies a basis for everolimus sensitivity. Science. 2012;338:221. doi: 10.1126/science.1226344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Hoff DD, Stephenson JJ, Jr, Rosen P, et al. Pilot study using molecular profiling of patients’ tumors to find potential targets and select treatments for their refractory cancers J Clin Oncol 2010284877–4883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.