Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), with over 170 countries as signatories, is the first ever international treaty to address the tobacco epidemic and promote global public health. It provides a roadmap for effective tobacco control strategies to reduce demand for and restrict supply of tobacco products and gives signatory countries a timetable to achieve specified milestones. Tobacco-related illness is a major component of the chronic diseases which cause a heavy human and economic toll. Tobacco control is thus a top priority in health promotion worldwide.

This is particularly true in China, where the smoking prevalence is high (1, 2), the price of cigarettes is low and affordable (3), the mortality from smoking related diseases is high (4), and the awareness level of the health risks of smoking is still relatively poor despite some improvements in the last 15 years (5). The country’s 300 million smokers and 740 million men, women and children exposed to secondhand smoke are at risk of suffering from cancers, stroke, heart and respiratory diseases and other tobacco-related illnesses (6). The cost of smoking in China was estimated to have gone up 154% in direct costs and 376% in indirect costs in the eight years from 2000 to 2008 (7). This presents a significant challenge to China, a country which has made the epidemiological transition from infectious diseases to chronic diseases in a relatively short period of time as a result of the rapid economic development in the last few decades which brought about changing lifestyles (8).

Despite becoming one of the first signatories to the FCTC in 2003, the pace of tobacco control in China is very slow and results are lackluster at best. In WHO’s ranking of the success of countries in tobacco control and FCTC compliance, China ranked in the bottom 20% (9). With so little to show since the country ratified the FCTC in 2005, there is a lot which needs to be addressed in order that tobacco control can really take root and become more effective as rapidly as possible.

This paper provides a framework for the analysis of the challenges and barriers in the implementation of the FCTC in China, as well as recommendations on how these challenges can be addressed. Views and suggestions presented here reflect the insights gleaned during the last decade by authors from discussions with senior political leaders in China’s Ministries of Health, Finance, Agriculture, State Administration on Taxation, and a number of think tanks and policy research institutes.

The Tobacco Economy

To understand the tobacco problem in China, an appreciation of the tobacco economy is essential. Tobacco is a state monopoly. China is by far the largest producer of tobacco in the world, producing 43% of the world total, which is more than the combined production of the next nine tobacco producing countries (10). The China National Tobacco Company (CNTC) is the largest producer of cigarettes in the world, producing 2.375 trillion cigarettes in 2010 (11), a staggering 40% increase over the previous decade (12), and amounts to 41% of the world’s total production in 2010 (10). Tobacco features significantly in government revenue, contributing in profits and taxes CNY752.9 billion in 2011 (US$118.5 billion, US$1 = CNY6.353 in Aug 2012) (13–15), amounting to 7.26% percent of government revenue (16). Furthermore, the livelihood of 20 million tobacco farmers (17), and millions more cigarette industry employees and over 300,000 cigarette retailers depend on tobacco farm subsidies, on growing tobacco leaf, on manufacturing jobs and on selling cigarettes for their livelihood (18). In tobacco leaf growing provinces, more than half of the provincial government’s revenue comes from tobacco. In the western province of Yunnan, for example, 77.8 percent of the provincial government’s tax revenues in 2010 came from tobacco (19–21).

The importance of the tobacco economy in China cannot be overstated, and is therefore a very important political consideration among government leaders. Even though the harmful effects of smoking are now well known, and it has also been established that tobacco leaf farming causes environmental degradation, deforestation and harms the health of tobacco leaf farmers (22), government leaders view the continued growth of the tobacco industry as integral to the political and economic wellbeing of the country. As in many countries, achieving economic growth and political stability is the number one concern for political leaders in China, and tobacco control is not high on their list of priorities. The health consequences of smoking are considerations which are further out into the future than the tenure of most current political leaders. These considerations shape the attitude towards the country’s tobacco control and FCTC implementation, and may explain the half-hearted efforts and miniscule resources that are devoted to it.

Of interest is the fact that the tobacco industry enjoys a certain amount of respectability in China, unlike its western counterparts. CNTC acknowledges that smoking is harmful and funds research to find “healthier” alternatives for those who do smoke. Outreach activities, philanthropy and community building are also on their agenda, including activities for young people, building schools, and organizing health education seminars and academic conferences etc. The general intention of CNTC’s philanthropy is similar to that of any other tobacco company: to win public support and build a positive image (23). While such outreach and public interest activities are also conducted by many major international tobacco companies such as Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco, the CNTC has the advantage of being able to work directly with central and local governments, allowing the CNTC to provide funding for and to implement government collaborative projects such as building schools and improving local highways. In the context of the size of the tobacco industry, these public interest and philanthropic projects constitute a miniscule percentage of the income of CNTC. Yet, all these programs help to justify the importance of the tobacco industry in the local community (24). A China Tobacco Museum in Shanghai is the largest such museum in the world. Built in 2004 and funded entirely by the industry, it is a shining example of the economic might and the social respectability the industry commands and the length that it goes to in order to ensure the reach and continued prosperity of the industry.

Barriers to Effective Tobacco Control

Structural and political barriers

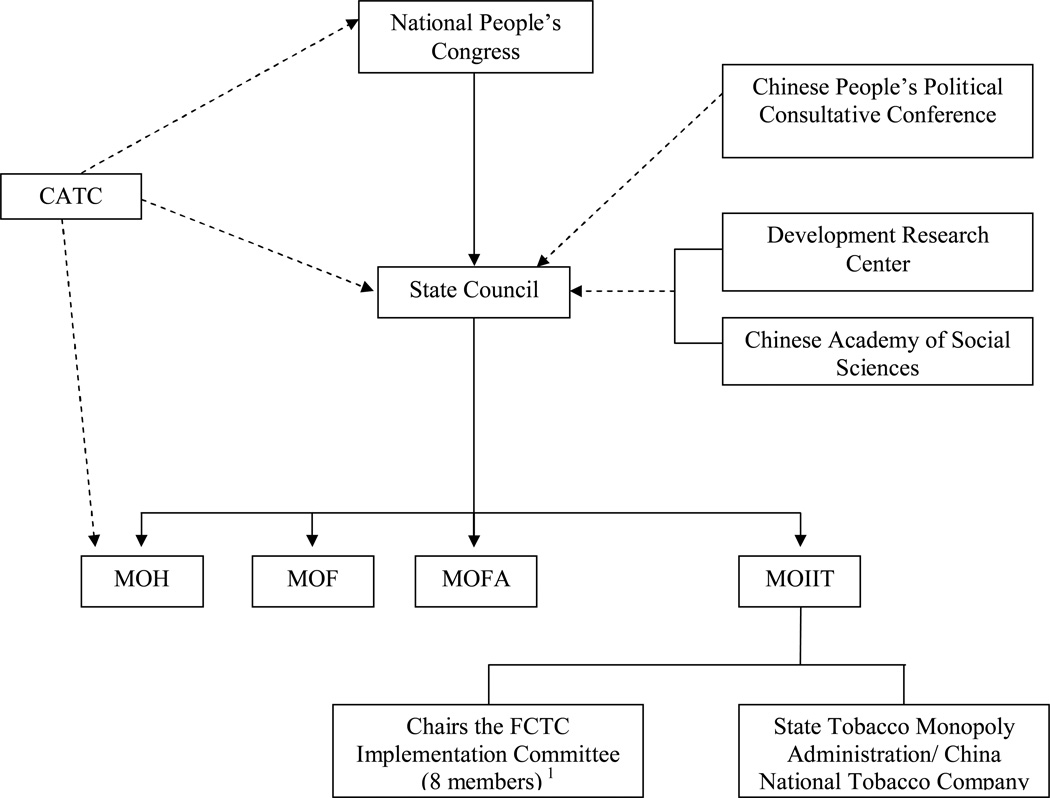

Examining where FCTC implementation is situated within the overall policy structure in the country is illuminating (Figure 1). Within the government structure, the highest powers reside with the National People’s Congress. Power flows through the State Council to the relevant ministries: Health, Finance, Agriculture, Taxation, and Industry and Information Technology. The National People’s Congress enacted the Tobacco Monopoly Law in 1991 aimed at protecting the industry and establishing it as a monopoly (18). The State Council is advised by the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the highest advisory mechanism in the country. The State Council gets policy inputs from its Development Research Center and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. CNTC falls under the jurisdiction of the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (STMA), which is responsible for supervising the enforcement of the Tobacco Monopoly law and relevant laws and regulations. In practice, STMA the regulatory body and CNTC the industry are the same entity, with one management structure. STMA sets overall policies and delegates to CNTC full authority to implement these policies. STMA is under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MOIIT) and has the goal of promoting the growth and stability of the tobacco economy (25–27). Thus both STMA and the industry itself have a strong stake to resist measures to implement FCTC.

Figure 1. Organizational Chart for Tobacco Control Policy in China.

Arrow: indicates the chain of decision-making

Dotted Line: represents an advisory relationship

MOF: Ministry of Finance

MOFA: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MOH: Ministry of Health

MOIIT: Ministry of Industry and Information Technology

CATC: Chinese Association on Tobacco Control

FCTC: Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

1. In addition to the four ministries shown, the other four members of the eight member committee are General Customs Administration, State Administration for Industry and Commerce, State Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, and the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration. The State Taxation Administration, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Education, and Communist Youth League are no longer full members of the committee since 2011 but are brought into discussion as needed.

The Chinese government has established an Inter-Agency FCTC Implementation Coordination Mechanism (ICM) in 2007 to implement the FCTC provisions. Currently, the ICM is made up of eight ministries which include the Ministry of Health (MOH), Ministry of Finance (MOF), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) the MOIIT, as well as the STMA. Of interest is the fact that the ICM is established under the MOIIT, and not the MOH. The Minister of MOIIT holds the chairmanship. The tobacco industry is under the purview of the MOIIT, and therein lies an intrinsic problem: the MOIIT’s role of spearheading the implementation of FCTC as chairman of the ICM is in direct conflict with its role as the ministry responsible for the management and development of the tobacco industry (28).

A good example of the ability of the state-owned industry to frustrate any tobacco control initiatives is the delay in implementing the warning labels on cigarette packages, as required by Article 11 of the FCTC. Years of wrangling took place among the MOH, the STMA, and the China Association on Tobacco Control (CATC) which for a long time is the only non-government organization devoted to tobacco control. The content and size of the new labels which resulted from such deliberations were found to comply with the letter, but not the intent, of the FCTC provision. Words of the health warning are in very small font size, or are in English, which is not understood by most smokers (29). Furthermore, graphic health warnings are considered inappropriate in the cultural context as cigarettes are often given as gifts on auspicious occasions. Cigarette companies, both Chinese companies and transnational companies, are eager to exploit this with elaborate packaging of cigarettes to be used as gifts (30). As the STMA is a key member of the government’s FCTC implementation committee, it can ensure that the measures taken cannot have the full effectiveness that is intended. New measures were introduced in April 2012 which called for larger font size and words to be in Chinese. The effectiveness of these new measures has yet to be studied. With regard to Article 15 of FCTC on restricted sales to minors, the legal minimum age to purchase cigarettes in China is 18. Enforcement of such a requirement among the hundreds of thousands of retailers is at best inconsistent.

With the tobacco economy enjoying such an important position, and with the industry well placed to protect its interests, tobacco control can be a politically sensitive topic. During the past 10 years, the authors have had numerous conversations at conferences as well as through personal contacts with senior officials from the administrative and legislative branches, research institutes and policy think tanks. Even though they are aware of the negative health consequences of smoking, they did not want to be unpopular among the vast smoking population. Nor are they keen to upset the status quo as far as the tobacco economy is concerned. Their unwillingness to champion the cause, or take an explicit policy stance on tobacco control, is a major barrier to the implementation of the FCTC.

Economic and social barriers

Economically, the barriers to tobacco control are daunting. As mentioned earlier, the contribution of tobacco taxation to government revenue is significant, particularly so in tobacco leaf growing provinces such as Yunnan, Hunan, Guizhou and Sichuan. Although research studies have demonstrated to the Chinese government, in particular MOF and State Administration for Taxation (SAT) officials, that raising tobacco tax would actually increase tobacco revenue despite a decrease in consumption, STMA is concerned that in the long run, the reduction of cigarette consumption would diminish the tobacco industry’s contribution to the Chinese economy (3, 31).

Contrary to the view held by senior policy leaders, empirical studies have shown that the potential negative impact of the reduction of cigarette sales on the employment of the tobacco industry and the livelihood of the tobacco farmers is not large, even for tobacco leaf growing provinces. It has been shown that with an increase of CNY1 (US$0.1574) in the specific excise tax on a pack of cigarettes, which is estimated to lead to a 3.1 billion pack reduction in sales, the tobacco industry employment could lose about 1600 positions, assuming there is no opportunity for re-employment in the short-run (3). Similarly, the income from tobacco farming is estimated to be reduced by CNY260 million (US$40.92million), assuming there is no crop substitution (3). In reality, however, there are always opportunities in both the industry sector and the farming sector for alternative employment and crop substitution. Even though the positive health impact of reduced production will lead to one million lives saved (3), and any negative impact on employment and farming would only be minimal, the Chinese government has often used the negative aspect as an excuse not to raise tobacco tax. International studies have also shown that reduction in cigarette consumption would not reduce overall employment in the economy, as the switch from cigarette consumption to consumption of other goods and services would create additional employment (32).

Another concern in the minds of policy leaders is the inflationary pressure that an increase in cigarette prices may have. In reality, however, the weighting of cigarette prices in the basket of commodities measured in the consumer price index is very small, with alcohol and tobacco together contributing only 3.49% (19). Yet the perception of possible inflationary pressure presents a barrier to any effort to raise tobacco tax, one of the most effective tobacco control measures (33).

Perhaps one reason that economic considerations can feature so prominently in tobacco control considerations is the fact that smoking has long been an integral part of the country’s social fabric. It is still a very acceptable social behavior, and serves as a social lubricant and connection builder. It enhances the daily social interactions of the smoker with his friends, boss and co-workers, as well as with relatives, all of whom very likely smoke (34). Offering cigarettes to friends is a symbol of friendship and a form of greeting and gift giving of cigarettes is a common custom, particularly at festivals and celebratory occasions such as birthdays and weddings.

China’s social norms apply not only to smokers, but also to nonsmokers who seem to accept that it is inevitable that smokers will smoke in their presence. Awareness of health risks has been very low among nonsmokers. As late as mid-2000, urban smokers in China considered that “light’ or “low tar” cigarettes were less harmful than “regular” or “full flavored” cigarettes (35). The Global Adult Tobacco Survey in 2010 noted that only 23.2% of adults in China believe that smoking causes stroke, heart attack and lung cancer and only 24.6% of adults in the country believe that exposure to tobacco smoke causes heart disease and lung cancer in adults and lung illnesses in children (2). Given that smoking and acceptance of smoking are social norms, and with these low levels of knowledge and awareness, social barriers to tobacco control in China are very challenging.

Equity Arguments in Tobacco Control

Article 6 of the FCTC requires signatory countries to raise tobacco tax to discourage cigarette consumption. Political leaders in China subscribe to the commonly held belief that making cigarettes more expensive by raising tobacco tax places an unfair burden on low-income smokers and negatively impact them disproportionately (32, 36). It is no wonder that the government drags its feet in implementing this single most effective measure in tobacco control, despite the fact that this regressivity argument has to be seen in the context that such tax increase may be progressive from a public health standpoint. Larger reductions in smoking have been found to occur for those smokers in the lower income groups (37). The reluctance of the Chinese government to raise tax is evidenced by the fact that the 2009 tax adjustments involved a complicated reclassification of cigarettes price levels and their corresponding tax rates, leading to a decrease in tax rates in cigarettes at certain price levels. Even such an adjustment led to considerable debate in the media about the fairness of it all (38).

Research in China has shown that expenditures on cigarettes constitute between 8 and 11% of total family expenditures in poor/near poor smoking households (39). Smoking households also spend less on food, housing, and education than nonsmoking households. Therefore, if households stopped buying cigarettes, these low-income smoking households could spend more money on essential goods. In addition to the negative impact of smoking on health, smoking also results in negative consequences in terms of human capital investment (40). The excessive medical spending attributable to smoking-related diseases and consumer spending on cigarettes has been estimated to be responsible for impoverishing 20 million residents in China during 1998 (41). Even though these evidence-based studies and research findings were published in major peer-reviewed journals, both English and Chinese, advocates still encounter challenges in communicating with top Chinese policymakers to disabuse them of the notion that raising tobacco tax is inequitable to the low-income population.

Recommendations to Confront the Challenges

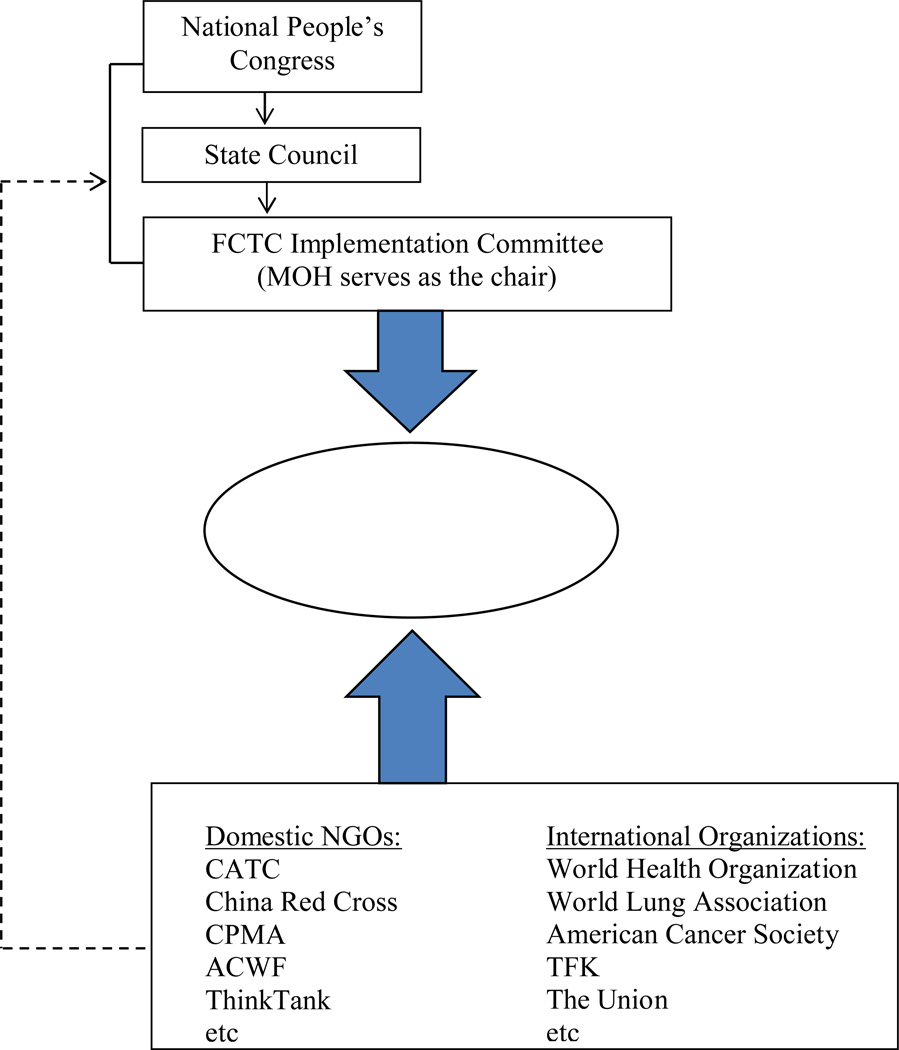

China has unique characteristics when it comes to implementing the FCTC. These include the country’s large population and number of smokers, national ownership of the tobacco industry, social and cultural backdrop and economic interest in the tobacco economy. During the past 10 years, numerous empirical studies have been published on the economic consequences of tobacco control in China, including the impact on government revenue, smoking prevalence, tobacco industry employment, and tobacco farming earnings. The evidence is there for a lot more to be done in control tobacco. Yet barriers persist. To overcome these barriers, the authors recommend a comprehensive strategy of top down and bottom up approaches. Figure 2 presents a conceptual framework in which policy leaders are influenced by a groundswell of popular support and they in turn initiate changes that will benefit tobacco control.

Figure 2. Conceptual Framework for Removing Current Barriers.

CATC: Chinese Association on Tobacco Control

CPMA: Chinese Preventive Medicine Association

ACWF: All-China Women’s Federation

ThinkTank: ThinkTank Research Center for Health Development

TFK: Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids

The Union: International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease

Top down approach

Under the current one-party political system, the central government has a clear mandate to set and implement overall national policy. The National People’s Congress can enact legislative changes such as removing the Tobacco Monopoly Law. The Premier is the head of the Government, which is directly under the President who is the head of State and Chairman of the ruling party. It is a top-down administrative system which has proven to be very effective. Once the top officials have decided to implement a policy initiative, the country has a well-structured administrative apparatus. The handling of public health crises and natural disasters in recent years has shown that the administrative apparatus can work efficiently and effectively when there is a political will. A good example is the handling of the SARS epidemic (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in 2003 (42). Therefore, the critical success factor to tobacco control in China is top level government leadership.

It is the authors’ view that the change in the top leadership in China which has just taken place in March 2013 provides a golden opportunity for new impetus in tobacco control. This once-in-a-decade change of leadership has ushered in a new generation of leaders in China. They are younger and have grown up in an era of reform and opening in China and are more open to western ideas and values. History has shown that each new leadership has sought to make their mark by initiating new philosophy and new initiative that seek to improve the well-being of the people. Tobacco control advocates should seize this window of opportunity to fight for an increase in tobacco tax, the most effective in the tobacco control toolkit. Of importance is the need to link any tax increase to the retail price of cigarettes. Another important tobacco control measure that the new leaders can use to demonstrate that they really have the intent to control the tobacco epidemic is to initiate legislation to enforce the smoke-free regulations with hefty penalties for those who do not comply.

It is therefore very important to provide these new top leaders with scientific evidence on policy impacts, costs of smoking, and benefits of tobacco control. In recent years, tobacco control advocacy from public health experts, civil society and international organizations as well as current international trends have resulted in top Chinese leaders feeling the need to take the moral high ground of supporting tobacco control more openly. Reaching and convincing this cohort of new leaders, especially those in MOF and SAT, to use price control measures such as tobacco taxation, and non-price control measures such as smoke-free rules and regulations will go a long way towards overcoming the many barriers to tobacco control in the country.

Bottom up approach

As shown in Figure 2, impetus for change can come from below as well. Even though China has 300 million smokers, nonsmokers still outnumber smokers. Experiences in many countries have shown that the tipping point in the battle against tobacco comes when non-smokers become aware that passive smoking is harmful to their health and that they have a right to a smoke-free environment. A groundswell of popular sentiment can be effective in influencing top leaders. Civil society, with non-government organizations, opinion leaders and other advocates can be a catalyst for change. Other countries have shown that civil society can play a significant role in advocacy, coalition building, providing evidence-based information, being a watchdog as well as providing services such as smoking cessation counseling (43). There is currently only a handful of non-government organizations working on tobacco control in China, notably the CATC. With funding from international organizations, the CATC has been able to become more proactive in organizing educational and intervention programs in tobacco control, cultivate opinion leaders, communicate with members of the National People’s Congress, the highest legislative body, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the highest advisory body. Furthermore, other NGOs such as the Chinese Red Cross, the All-China Women’s Federation as well as academic bodies such as the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association have begun to devote efforts in recent years to tobacco control as part of their mission. The formation and involvement of more grassroots organizations to advocate for non-smoker’s rights will be a step in the right direction. At the same time, international organizations such as the World Health Organization, the World Lung Association, American Cancer Society, Red Cross, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease and philanthropic organizations such as Gates Foundation and Bloomberg Initiative are supporting projects and building competencies in China.

With the increasingly prevalent use of internet technology among the population, these organizations take advantage of the social media and web technology as well as the mainstream media to increase knowledge of the health risks of active and passive smoking, and to raise the awareness of non-smokers to their right to smoke free air in public places. The momentum for change from the community level will provide policy leaders at the top with a lot of incentives to take action and to make more effective use of the tools in the tobacco control toolkit.

Structural change

The major economic conflict for the Chinese government concerning implementation of the FCTC provisions is the government ownership of the tobacco industry and the STMA and CNTC being one and the same entity. With market-oriented activities and modern concepts of government oversight and monitoring increasingly becoming features of the Chinese economy, separating the tobacco industry from its regulatory state agency would be a step in the right direction. This will also move towards the goal of privatization of the tobacco industry. Two potential factors could lead the Chinese government to privatize the tobacco industry. First, with the growth of the Chinese economy, the role of the tobacco industry in terms of its economic contribution to central government revenue has been declining, as evidenced by the decreasing share of the industry’s profit and tax contribution to central government revenue. Second, since China joined the World Trade Organization, transnational tobacco companies have become increasingly active in the Chinese cigarette market. Chinese tobacco economics research committees have begun to study whether the Chinese cigarette industry will become a “sunset” industry in the future. Top government officials also have been looking at examples of the privatization of the cigarette industry in foreign countries, such as in Korea, Thailand and Turkey. The MOH and the CATC have begun officially endorsing the idea of withdrawal of government ownership and the transfer of CNTC to the private sector. Having the CNTC as a private entity most likely would result in a less direct economic conflict of interest for the government, and make it less able to resist the implementation of FCTC provisions. Such a fundamental structural change will need to be achieved through the NPC which can legislate the necessary changes to the Tobacco Monopoly Law. At the level of the ICM, changing the leadership of the committee from the MOIIT to the MOH will elevate the emphasis placed on health as the most important consideration in the implementation of the FCTC.

A structural change of privatizing the tobacco industry will also have ramifications in tobacco farming and address tobacco control from the supply side. Currently CNTC controls the sources of leaf production, allocation of leaf quotas and cigarette marketing channels. The CNTC has been subsidizing tobacco farmers and imposing a tobacco leaf tax as a source for local government revenue to ensure that the government can enforce the quota for CNTC (44). With a structural change, a private market for tobacco will enable farmers to switch to other crops which may be more lucrative. Pilot experiments of crop substitution for tobacco farmers to grow other cash crops has shown that this leads to increased output per acre and increased income for the farmers (17).

Conclusion

It is clear that China faces many barriers and major challenges to the effective implementation of tobacco control measures under the FCTC. The past seven years since the ratification of the FCTC, the Chinese government has yet to show its determination to give full effort to implement tobacco control measures in the country. Achievements are few and results dismal. With China becoming an increasingly visible player on the world stage, and being looked upon as having the resources to address problems to promote the health and wellbeing of its own people, it is incumbent upon the new leadership to show that there is the political will to tackle this problem. Separation of the STMA and the CNTC into distinct entities as regulator and industry respectively will be a first step towards privatizing the tobacco industry. Raising tobacco taxation and linking such tax increase to the retail price of cigarettes will reduce consumption, improve health and safe lives. A national law to enforce smoke-free public place regulations with hefty cash penalties will go a long way towards protecting non-smokers from exposure to secondhand smoke.

China has the dubious distinction of having the largest number of active and passive smokers in the world, the largest area of farmland for tobacco leaf production and is the world’s largest cigarette manufacturer. Success in addressing the tobacco problem in China would significantly decrease the global burden of tobacco-related illnesses and death, and promote global health. A comprehensive formula of strong political leadership, growing grassroots movements, increasing community awareness and changing social norms, coupled with structural changes to the tobacco industry to dislodge it from the entrenched position of power are essential ingredients to meet the challenges of tobacco control in China.

References

- 1.Li Q, Hsia J, Yang G. Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(25):2469–2470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1102459. Epub 2011/06/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Fact Sheet China. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu TW, Mao Z, Shi J, Chen W. The role of taxation in tobacco control and its potential economic impact in China. Tobacco control. 2010;19(1):58–64. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031799. Epub 2009/12/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu D, Kelly TN, Wu X, Chen J, Samet JM, Huang JF, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking in China. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(2):150–159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802902. Epub 2009/01/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Wang JJ, Wang CX, Li Q, Yang GH. Awareness of tobacco-related health hazards among adults in China. Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES. 2010;23(6):437–444. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(11)60004-4. Epub 2011/02/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang G, Hu A. Tobacco Control and the Future of China. Beijing: The Economic Daily Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L, Sung HY, Mao Z, Hu TW, Rao K. Economic costs attributable to smoking in China: update and an 8-year comparison, 2000–2008. Tobacco control. 2011;20(4):266–272. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.042028. Epub 2011/02/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang G, Kong L, Zhao W, Wan X, Zhai Y, Chen LC, et al. Emergence of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61366-5. Epub 2008/10/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang GH, Li Q, Wang CX, Hsia J, Yang Y, Xiao L, et al. Findings from 2010 Global Adult Tobacco Survey: implementation of MPOWER policy in China. Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES. 2010;23(6):422–429. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(11)60002-0. Epub 2011/02/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksen M, Mackey J, Ross H. The Tobacco Atlas. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Full year analysis of national production of cigarettes 2010 (in Chinese) [[8/28/2012]]; Available from: http://www.china-consulting.cn/article/html/2011/0527/101538.php. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Editorial. China advised to "put a brake" on tobacco industry. China Daily US Edition. 2011 Jun 1; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Editorial. Cost of Tobacco. China Daily US Edition. 2011 Nov 11; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.China Tobacco. 2011 Report of the National Working Conference on tobacco. [8/28/2012];2011 Available from: http://www.tobacco.gov.cn/html/48/4801/3662206_n.html.

- 15. www.people.com.cn. CNTC Daily Profits CNY 320 million Beijing2012. [8/28/2012]; Available from: http://health.people.com.cn/GB/14740/22121/17311892.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16. www.china.com.cn. Total Government Revenue CNY10374 Billion, a 24.8% Increase Beijing2012. [8/28/2012]; Available from: http://finance.china.com.cn/news/gnjj/20120120/494751.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li VC, Wang Q, Xia N, Tang S, Wang CC. Tobacco crop substitution: pilot effort in china. American journal of public health. 2012;102(9):1660–1663. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300733. Epub 2012/07/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T, Xiong B. Tobacco Economy & Tobacco Control (in Chinese) Beijing: Economic Science Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2010. Beijing: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yunnan Provincial Department of Finance. The report on the implementation of local budgets in 2010 and the local fiscal budget draft in 2011 in Yunnan Province. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yunnan Provincial Government Information website of the Bureau of Statistics. 2010 report on economic development in Yunnan. 2010 Available from: www.stats.yn.gov.cn.

- 22.Lecours N, Almeida GE, Abdallah JM, Novotny TE. Environmental health impacts of tobacco farming: a review of the literature. Tobacco control. 2012;21(2):191–196. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050318. Epub 2012/02/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. Tobacco Companies’ Public Relations Efforts: Corporate Sponsorship and Advertising. In: Davis R, Gilpin E, Loken B, Viswanath K, Wakefield M, editors. Tobacco Control Monograph 19: The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. pp. 179–209. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirschhorn N. Corporate social responsibility and the tobacco industry: hope or hype? Tobacco control. 2004;13(4):447–453. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006676. Epub 2004/11/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xinhua News Agency. [05/22/2013];Ministry of Industry and Information Technology inaugurated. 2008 Available from: http://www.china.org.cn/government/news/2008-06/30/content_15906787.htm.

- 26.National Development and Research Council of China. [05/23/2013];State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (China National Tobacco Corporation) Available from: http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/mfod/t20050520_0881.htm.

- 27.TobaccoChina. 2013 New Year Address of Mr Jiang Chengkang, President of State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (in Chinese) [05/21/2013]; Available from: http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/mfod/t20050520_0881.htm.

- 28.Lv J, Su M, Hong Z, Zhang T, Huang X, Wang B, et al. Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in mainland China. Tobacco control. 2011;20(4):309–314. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.040352. Epub 2011/04/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wan X, Ma S, Hoek J, Yang J, Wu L, Zhou J, et al. Conflict of interest and FCTC implementation in China. Tobacco control. 2011 doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041327. Epub 2011/06/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu A, Jiang N, Glantz SA. Transnational tobacco industry promotion of the cigarette gifting custom in China. Tobacco control. 2011;20(4):e3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.038349. Epub 2011/02/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu TW, Mao Z, Shi J. Recent tobacco tax rate adjustment and its potential impact on tobacco control in China. Tobacco control. 2010;19(1):80–82. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032631. Epub 2009/10/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warner KE. The economics of tobacco: myths and realities. Tobacco control. 2000;9(1):78–89. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.78. Epub 2000/02/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. WHO technical manual on tobacco tax administration. Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan Z. Socioeconomic predictors of smoking and smoking frequency in urban China: evidence of smoking as a social function. Health promotion international. 2004;19(3):309–315. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah304. Epub 2004/08/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elton-Marshall T, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Jiang Y, Hammond D, O'Connor RJ, et al. Beliefs about the relative harm of "light" and "low tar" cigarettes: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Tobacco control. 2010;19(Suppl 2):i54–i62. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029025. Epub 2010/10/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Gender, Women, and the Tobacco Epidemic. Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasserman J, Manning WG, Newhouse JP, Winkler JD. The effects of excise taxes and regulations on cigarette smoking. Journal of health economics. 1991;10(1):43–64. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90016-g. Epub 1991/04/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. cq.qq.com. Raising tobacco tax: experts have something to say (in Chinese) [05/26/2013];2009 Available from: http://cq.qq.com/a/20090622/000412.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu TW, Mao Z, Liu Y, de Beyer J, Ong M. Smoking, standard of living, and poverty in China. Tobacco control. 2005;14(4):247–250. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010777. Epub 2005/07/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H. Tobacco control in China: the dilemma between economic development and health improvement. Salud publica de Mexico. 2006;48(Suppl 1):S140–S147. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000700017. Epub 2007/08/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Rao K, Hu TW, Sun Q, Mao Z. Cigarette smoking and poverty in China. Social science & medicine (1982) 2006;63(11):2784–2790. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.019. Epub 2006/09/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Y. The SARS epidemic and its aftermath in China: a political perspective. In: Knobler S, Mahmoud A, Lemon S, editors. Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak: Workshop Summary Institute of Medicine Forum on Microbial Threats. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Champagne BM, Sebrie E, Schoj V. The role of organized civil society in tobacco control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Salud publica de Mexico. 2010;52(Suppl 2):S330–S339. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800031. Epub 2011/02/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu TW, Mao Z, Jiang H, Tao M, Yurekli A. The role of government in tobacco leaf production in China: national and local interventions. Int J of Public Policy. 2007;2(3/4):235–248. [Google Scholar]