Abstract

Biomaterial-associated infection is one of the most common complications related with the implantation of any biomedical device. Several in vivo imaging platforms have emerged as powerful diagnostic tools to longitudinally monitor biomaterial-associated infections in small animal models. In this study, we directly compared two imaging approaches: bacteria engineered to produce luciferase to generate bioluminescence and reactive oxygen species (ROS) imaging of the inflammatory response associated with the infected implant. We performed longitudinal imaging of bioluminescence associated with bacteria strains expressing plasmid-integrated luciferase driven by different promoters or a strain with the luciferase gene integrated into the chromosome. These luminescent strains provided adequate signal for acute (0–4 days) monitoring of the infection, but the bioluminescence signal decreased over time and leveled off by 7 days post-implantation. This loss in bioluminescence signal was attributed to changes in the metabolic activity of the bacteria. In contrast, near-infrared fluorescence imaging of ROS associated with inflammation to the implant provided sensitive and dose-dependent signals of biomaterial-associated bacteria. ROS imaging exhibited higher sensitivity than the bioluminescence imaging and was independent of the bacteria strain. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of inflammatory responses represents a powerful alternative to bioluminescence imaging for monitoring biomaterial-associated bacterial infections.

Keywords: Biomaterial-associated infection, Bioluminescence, Near infrared Fluorescence, Noninvasive monitoring, Staphylococcus aureus

1. Introduction

Device-related bacterial infections are a growing healthcare problem [1–3], accounting for more than 50% of the 2,000,000 annual hospital-acquired infections associated with indwelling devices and implants in the United States [2]. Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common pathogens associated with these cases. Bacterial colonization and biofilm development can lead to both malfunction of the device and systemic infection, since biofilms are complex cooperative communities, and such biofilm bacteria are nearly impervious to antimicrobial therapy or host defense mechanisms [4,5]. In most cases, the affected devices must be removed to eliminate the infection, given the fact that currently there are no drugs that specifically target bacteria in biofilms [6–8].

A requirement to efficiently treat implant-associated infections are in vivo monitoring approaches that allow better understanding and control of biofilm formation, together with novel methods for targeting efficient drug candidates [9]. Optical imaging of bacterial infections in vivo using engineered bioluminescent bacterial strains is a widely used approach for spatial and temporal assessment of the infection [10]. This method is based on bioluminescent bacteria expressing a luciferase-based reporter system that emits light that can be monitored longitudinally and nondestructively in the same animal.

In view of the fact that biomaterial-associated infections modulate the inflammatory response to the biomaterial, changes in inflammatory markers may be used to improve monitoring of an ongoing infection [11]. In particular, reactive oxygen species (ROS) form part of the oxygen-dependent bactericidal mechanisms that phagocytic cells employ [12]. Near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging probes, such as hydrocyanines, allow real-time fluorescence imaging and ROS detection in the vicinity of an implant [13]. Moreover, NIRF imaging is an excellent noninvasive method for whole-body scanning that can determine the extent of the infectious disease throughout the body, especially in clinically challenging cases involving trauma, infection, and compromised tissue beds.

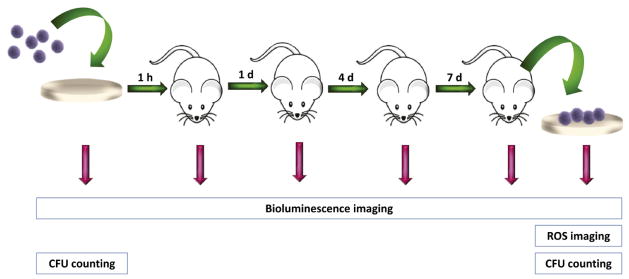

Herein, we directly compared two imaging approaches of implant-associated infection: bacteria engineered to produce luciferase to generate bioluminescence and ROS imaging of the inflammatory response associated with the infected implant. These approaches were correlated to bacterial counts before and after 7 days of implantation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline for comparison of bioimaging approaches of biomaterial-associated infection. PHOHHx disks were pre-colonized with engineered bioluminescent bacteria. Following counting bacteria and bioluminescence imaging, disks were implanted subcutaneously. Bioluminescence was measured at 0, 1, 4, 7 days. After ROS imaging at day 7, disks were retrieved and analyzed for bacterial counts and immunostaining.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Disk fabrication

Poly(3-hydroxyoctanoate-co-hydroxyhexanoate), PHOHHx, was kindly provided by Bioplolis S.L. The monomer composition of PHOHHx was determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) as previously described [14] and consisted in 8.5% 3-hydroxyhexanoate (OH-C6) and 91.5% 3-hydroxyoctanoate (OH-C8). An optimized downstream processing was applied to eliminate endotoxins as previously described [15]. Briefly, 1 g of PHOHHx was dissolved in 100 mL of chloroform at 40 °C under vigorous stirring, the suspension was pressure filtered and the polymer was precipitated by addition of non-solvent methanol. Finally, the polymer was dried under vacuum at 40 °C for 48 h. This procedure was repeated two times to obtain PHOHHx with endotoxin units (EU) <20 EU g−1, in compliance with the endotoxin requirements for biomedical applications (FDA) [16]. The endotoxin content was measured using a Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL)-test (Pyrogent Plus Single Test Kit, Lonza) and the endotoxin content was determined to be <15 EU g−1.

Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) disks (6 mm diameter) were coated with PHOHHx by solvent-casting. PHOHHx dissolved in chloroform (2% w/v) was applied over sterile, endotoxin-free PET disks (kindly supplied by ACCIONA, Barcelona, Spain), in a dust-free atmosphere. The coatings were allowed to dry for 72 h at room temperature and the resulting PHOHHx-coated disks (referred to hereafter as PHOHHx disks) were sterilized with ethylene oxide at 40 °C.

2.2. Bacterial strains, media and growth conditions

The bacterial strains used throughout this study were Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus ATCC 12600, its two derivate luminescent strains S. aureus (pAmiBlaz) and S. aureus (pAmiSPA), and the S. aureus Xen29 strain containing lux operon stably inserted into the chromosome (Caliper Life Sciences, PerkinElmer Company). All bacterial strains were pre-cultured in trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The appropriate selection antibiotics, chloramphenicol (10 μg mL−1) or kanamycin (200 μg mL−1), were added when indicated. Trypticase soy broth (TSB, Difco) was used as the growth medium to culture all bacterial pathogens.

2.3. Construction of S. aureus luminescent strains

Bioluminescent S. aureus strains were generated by transforming ATCC 12600 strain with a modified Photorhabdus luminescens luxCDABE (lux) gene cluster using the pAmiBlaz or pAmiSPA plasmids. To construct the vectors, blaZ (β-lactamase) and spa2 (protein A) promoters were inserted into promoterless-lux cloning vector pAmilux [17] to yield pAmiBlaz or pAmiSPA plasmid, respectively. Vectors were introduced into the cells by electroporation as previously described [18]. Transformants were selected on TSA plates containing chloramphenicol (10 μg mL−1). Successful transformation was confirmed by bioluminescent colonies screening using an IVIS Lumina bioimaging system (Xenogen).

Expression of lux operon in pAmiBlaz vector was driven by the BlaZ promoter, whereas in pAmiSPA the lux operon was controlled by the protein A promoter. These two promoters were used with the aim to generate different expression patterns. The BlaZ promoter was used for constitutive expression of luciferase. In contrast, the S. aureus protein A is involved in the development of biofilm-associated infections [19]; therefore the spa promoter drives the expression of luciferase during biofilm development. S. aureus Xen29 (Caliper, PerkinElmer) is a commonly used, commercially available strain containing luciferase construct stably integrated into the chromosome.

2.4. Preparation of hydro-indocyanine green

Hydro-indocyanine green (H-ICG) was synthesized from indocyanine green dye (ICG) (Acros Organics) by reduction with sodium borohydride as described [13]. Briefly, 2 mg of ICG was dissolved in 4 mL of methanol and reduced with 2–3 mg of sodium borohydride (Aldrich). Solvent was removed by stirring reaction mix for 5 min under reduced pressure. The dye was nitrogen capped and stored overnight at −20 °C.

2.5. Sample preparation, implantation and bioimaging

To test the biofilm formation of the S. aureus parental strain and its bioluminescent derivatives in vivo, bacterial strains were first cultivated overnight in TSB with aeration at 37 °C. The cultures were diluted with fresh TSB to reach absorbance A595 = 0.1 and incubated for 3–4 h to A595 = 0.7. Afterwards, bacterial test inocula were prepared in 2 mL of phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2 (PBS), to serve as a cell suspension. Bacterial suspensions (3.5 × 102 to 3.5 × 108 CFU/mm2) were placed on sterile endotoxin-free PHOHHx disks. Prior to implantation, disks pre-colonized with bacteria were placed in sterile containers and incubated 30 min under static conditions at 37 °C.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed [20]. All surgical procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Sterile, endotoxin-free disks as well as bacteria pre-colonized disks were implanted subcutaneously in the back of 6–8 weeks old male BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories) anesthetized by isofluorane. A single 1 cm incision was made on the dorsum proximal to the spine, and a subcutaneous pocket laterally spanning the dorsum was created. Sterile disks (two per mouse, one on either side of the spine) were implanted, and the incision was closed using sterile wound clips. For analysis of each experimental group, 3 or more mice were imaged.

For bioimaging of luminescent bacteria, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and imaged with a CCD camera (IVIS Lumina® bioimaging system, Xenogen) directly following implantation and 1, 4, 7 days post implantation. Bioluminiscence was integrated using Living Image® software Version 3.1 (Xenogen). Total counts from S. aureus were collected during a 2 min exposure using the IVIS Imaging System and Living Image software (Xenogen Corporation). Bioluminescence images were displayed using a pseudo-color scale (blue representing the least-intense light and red representing the most-intense light) that was overlaid on a gray-scale image to generate a two-dimensional image of the distribution of bioluminescent bacteria in the animal. To account for the background luminescence, one uninfected mouse was imaged along with the infected animals. The total counts from a region were quantified using the Living Image software package (Xenogen Corporation), and the data are presented as total counts contained within each region.

For bioimaging of ROS, 30 μL of H-ICG at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 in sterile water was injected near the vicinity of the implant as described [13]. The same animals used to image bioluminescence were used to evaluate NIRF signals. Thirty minutes after dye injection, the whole body of the animal was scanned in an IVIS Lumina® bioimaging system (Xenogen). Biofluorescence was integrated using Living Image® software Version 3.1 (Xenogen). ROS bioimaging was performed 7 days post-implantation.

2.6. Explant analysis

After euthanasia, disks were carefully explanted with the intact surrounding tissue to avoid disrupting the cell-material interface. For immunostaining, explants were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek) and cryosectioned at 10 μm. Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with monoclonal antibodies (Abcam) against macrophage (CD68) or neutrophil (NIMP-R14) markers. Alternatively, samples were incubated with monoclonal antibodies against S. aureus (Abcam). AlexaFluor 488-conjugated goat antibody (Invitrogen) was used as a secondary antibody. The sections were mounted with antifade mounting media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Labs) and imaged under a Nikon C1 confocal microscope system. Five-six fields per sample were acquired and ImageJ software was used to count the fluorescently labeled cells.

For CFU bacteria counting, each explant was placed in a glass tube containing 1 mL of PBS and sonicated for 10 min in an ultrasonic bath to remove adhered bacteria. Afterwards, two more sonicating cycles were applied (5 min and 30 s) interspersed with 30 s of vortexing. Serial dilutions were plated on TSA plates supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg mL−1) to determine the number of viable S. aureus Xen29 or chloramphenicol (10 μg mL−1) to determine the number of S. aureus carrying pAmiBlaZ or pAmiSPA. CFU were determined after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA using Tukey post-hoc test with P ≤ 0.05 considered significant. Pair-wise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni post-hoc test with P ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Bioluminescent S. aureus permits short-term monitoring of Biomaterial-Associated Infections

To monitor infection profile in an in vivo murine model, PHOHHx polymer disks were loaded with bioluminescent S. aureus strains carrying different genetic configurations of the lux operon. S. aureus (pAmiBlaz) and S. aureus (pAmiSPA) contained the luciferase construct in an antibiotic-selective plasmid, whereas S. aureus Xen29 contained the luciferase gene integrated into the bacterial chromosome.

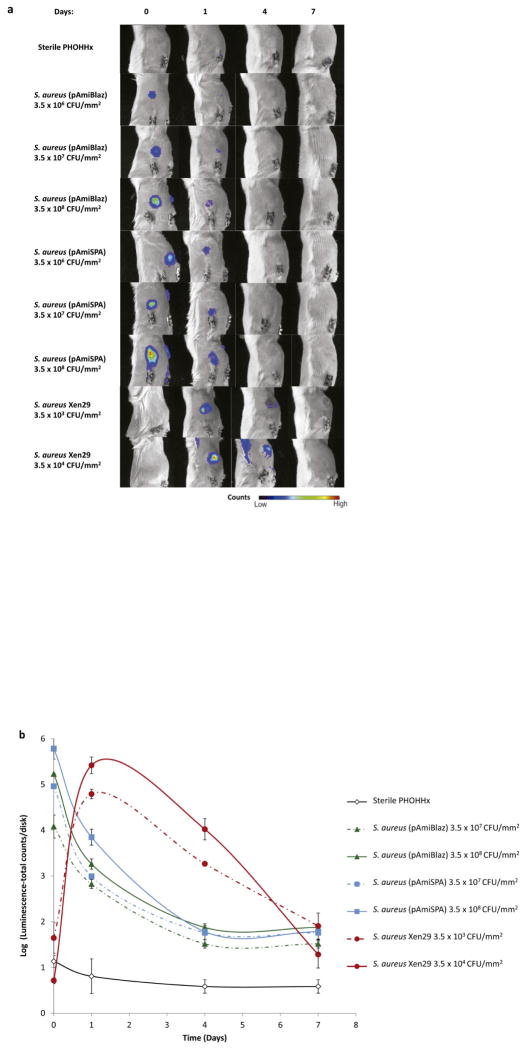

PHOHHx disks pre-colonized with different inocula of S. aureus luminescent strains were implanted subcutaneously in BALB/c mice and bioluminescent signal intensity was monitored over a 7-day period. For infected implants, the bioluminescence signal was significantly higher than readings for sterile PHOHHx implants (Fig. 2a,b). Bioluminescent signal for S. aureus (pAmiBlaz) and S. aureus (pAmiSPA) strains was detected only in a local site with high bacterial densities (3.5 × 106 – 3.5 × 108 CFU/mm2), while lower bacterial densities did not emit detectable signal at any time point (Fig. 2a). The higher inocula, 3.5 × 107 and 3.5 × 108 CFU/mm2, of both strains had concentration-dependent increases in bioluminescent signals and showed maximal value 1 h post-implantation (Fig. 2b). Differences in bioluminescence levels due to differences in promoter activity were evident. Over the next 4 days post-implantation, bioluminescent signal progressively decreased for both S. aureus (pAmiBlaZ) and S. aureus (pAmiSPA) strains, and only the highly expressed spa promoter provided detectable signal. At day 7 post-implantation, the bioluminescence signal for all strains was equivalent, although the signal was higher than sterile controls (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Temporal progression of PHOHHx implant associated infection using different S. aureus luminescent strains. (a) Bioimaging data of animals scanned in an IVIS® imaging system for monitoring the intensity of S. aureus (pAmiBlaz), S. aureus (pAmiSPA) and S. aureus Xen29 luminescent signal. (b) Quantification of luminescence data from animals receiving subcutaneous PHOHHx implant pre-colonized with different S. aureus (pAmiBlaz), S. aureus (pAmiSPA) and S. aureus Xen29 CFU (n ≥ 3 mice/time point).

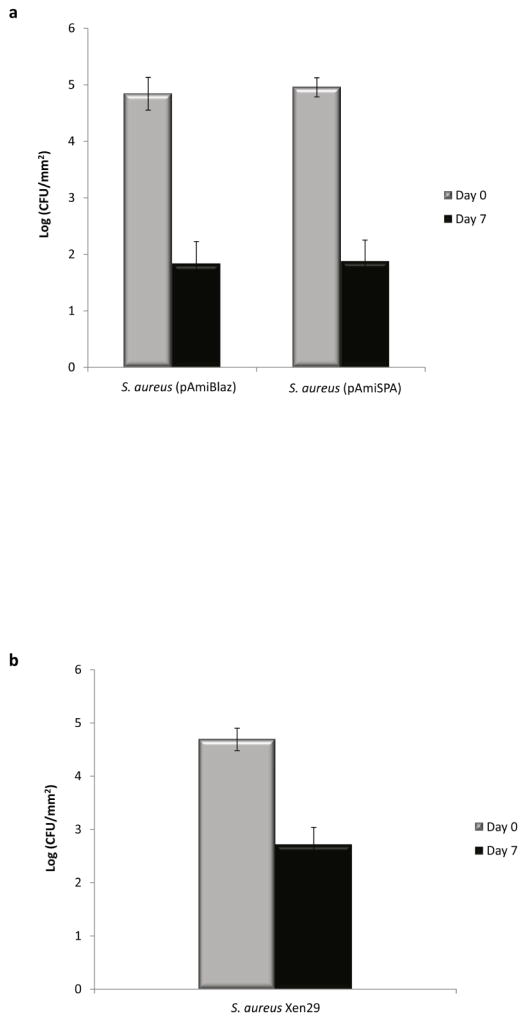

Because bacterial luciferase is an energy-requiring oxygenase and as such a reporter of cell metabolic activity, it is likely that during the stationary phase of bacterial growth the intensity of luminescent signal is related to the cell metabolic activity rather than to the promoter activity. Additionally, the drop-off in signal could possibly be due to loss of the plasmid and/or reductions in bacteria numbers. The correlation between signal intensity and the number of bacteria containing plasmid was investigated by growing S. aureus (pAmiBlaz) and S. aureus (pAmiSPA) cells on the plates containing selective marker. CFU of bacteria carrying pAmiBlaz or pAmiSPA prior to implantation was compared with CFU of bacteria harboring plasmid up on disk retrieval on day 7. A decreased number of bacteria carrying plasmid was clearly observed (Fig. 3a) when grown on selective plates (see Materials and methods section for details), indicating a possible cause for the loss of bioluminescence signal.

Figure 3.

Quantification of plasmid-containing bacteria (a) and number of viable cells (b). (a) S. aureus cells containing pAmiBLAZ or pAmiSPA previous to implantation and 7 days-post implantation was screened on TSA plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (10 μg mL−1). (b) The number of viable S. aureus Xen29 cells previous to implantation and 7 days-post implantation determined on TSA kanamycin (50 μg mL−1) plates.

To examine whether the stable integration of the lux operon into the bacterial chromosome overcomes this limitation of the S. aureus (pAmiBlaz) and S. aureus (pAmiSPA) strains carrying the luciferase construct in a plasmid, we tested the S. aureus Xen29 strain. Using S. aureus Xen29, we were able to monitor the infection in the experimental model applying lower bacterial inoculums (3.5 × 103 and 3.5 × 104 CFU/mm2) (Fig. 2a,b). Following implantation of pre-colonized disks, the bioluminescence measurements increased exponentially over 24 h and peaked on day 1 post-implantation (approximately 5.5 log (luminescence-total counts/disk) for bacterial inoculum 3.5 × 104 CFU/mm2 and 4.8 log (luminescence-total counts/disk) for bacterial inoculum 3.5 × 103 CFU/mm2). The high signal for Xen29 compared to the other strains is attributed to differences in the promoter and construct configuration. However, similar to our observations for the strains carrying the luciferase plasmid, the bioluminescence signal decreased at day 4 post-implantation and reached equivalent levels as the other bioluminescent strains by day 7 (Fig. 2b). Bacteria counts indicated significant loss in the number of viable bacteria at explant (Fig. 3b); this loss in viable bacteria is mostly likely due to an inflammatory response and accounts for the loss in bioluminescence signal. Taken together, these results demonstrate that bacteria strains expressing luciferase can be used to image infection short-term but none of the strains tested was suitable for monitoring chronic infections above a bacteria threshold (3.5 log CFU/mm2) in this model of biomaterial-associated infection.

3.2. NIRF imaging of infection-associated inflammation

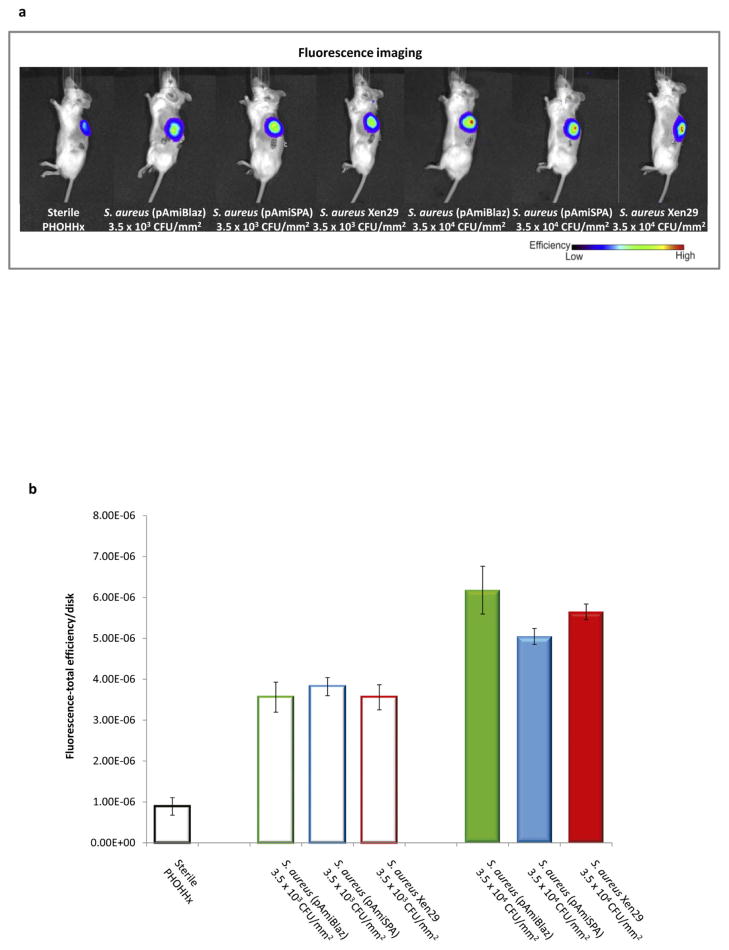

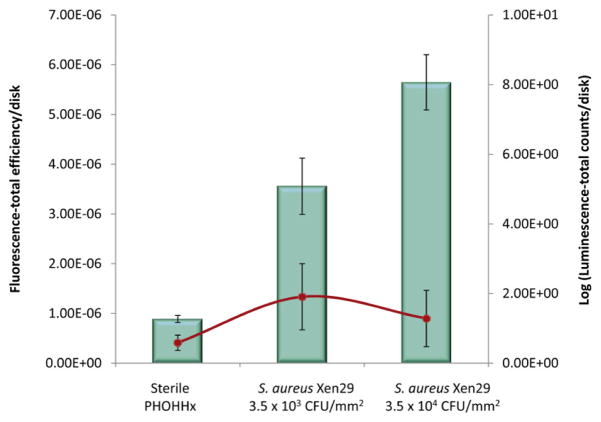

We next applied NIRF imaging as a tool to examine biomaterial-associated infections using hydrocyanine dyes as an alternative to bioluminescent bacteria. Because inflammation patterns are a key correlate of the presence of an infection [21,22], the NIRF ROS sensor H-ICG was used to measure the levels of local inflammation associated with the infected biomaterial. Based on previous studies where biomaterial associated inflammation was longitudinally monitored using H-ICG [13,23], we observed the clearest evidence of NIRF signal at 7 days. Therefore, at 7 days post-implantation, H-ICG was injected in the vicinity of infected PHOHHx disks with a low bacteria inoculum (3.5 × 103 or 3.5 × 104 CFU/mm2) and animals were imaged in order to directly compare the two imaging modalities, NIRF and bioluminescence (Fig. 4). Increases in bacteria dose were clearly detected by imaging ROS via H-ICG signal, and these levels were significantly higher than the ROS signal for inflammation associated with sterile implants (Fig. 4b). Importantly, the H-ICG signal was independent of the bacteria strain used. In contrast, these lower bacteria densities were undetectable by imaging of bioluminescence (Fig. 5). NIRF imaging of infection-related inflammation using H-ICG provided readings that correlated with bacterial concentration independently of the S. aureus strain used (Fig. 4b; Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

NIRF imaging approach to detect PHOHHx implant-associated infection with different S. aureus strains at 7 days post-implantation. (a) Bioimaging data of animals scanned in an IVIS® imaging system for in vivo ROS imaging of inflammation associated with implant infection using H-ICG sensor. (b) Quantification of ROS fluorescence data from mice with PHOHHx implants incubated with 3.5 × 103 CFU/mm2 (open bars), 3.5 × 104 CFU/mm2 (closed bars) and sterile PHOHHx implant (open black bar) (n ≥ 3 mice/time point).

Figure 5.

Comparative representation of near IR fluorescence total efficiency (left axis) and bioluminescence total count (right axis) of S. aureus pre-colonized disks. NIRF imaging (bars) and bioluminescence imaging (line) of same S. aureus pre-colonized disks was compared in the same animals at 7 days post-implantation.

3.4. ROS signal correlate with inflammatory cell recruitment of infected biomaterials

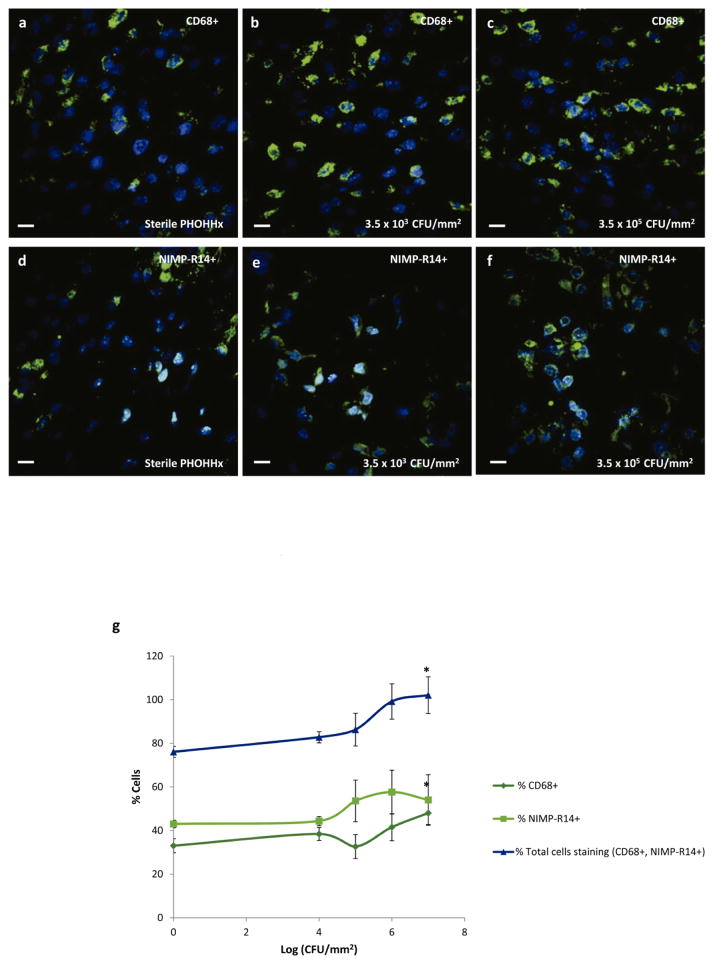

We analyzed macrophage (CD68) and neutrophil (NIMP-R14) recruitment to the implant at day 7 post-implantation by immunostaining (Fig. 6a–f). Both macrophages and neutrophils were recruited to the implant. Quantification of the number of cells staining for these markers revealed an increasing trend in neutrophil and macrophage recruitment with increased bacteria dose (Fig. 6g).

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical staining for macrophages (CD68+) and neutrophils (NIMP-R14) in infected implant-associated inflammation. (a–c) Representative co-localization images of CD68+ and DAPI stained nuclei in (a) sterile PHOHHx implant, (b) PHOHHx implant pre-colonized with 3.5 × 103 CFU/mm2, and (c) PHOHHx implant pre-colonized with 3.5 × 105 CFU/mm2. (d–f) Representative co-localization images of NIMP-R14+ and DAPI stained nuclei in (d) sterile PHOHHx implant, (e) PHOHHx implant pre-colonized with 3.5 × 103 CFU/mm2, and (f) PHOHHx implant pre-colonized with 3.5 × 105 CFU/mm2. (g) Quantification of CD68+, NIMP-R14+ and total number of cells stained positive for CD68+ and NIMP-R14+ (n = 4 disks/bacterial concentration, *P < 0.05). Scale bar 10 μm.

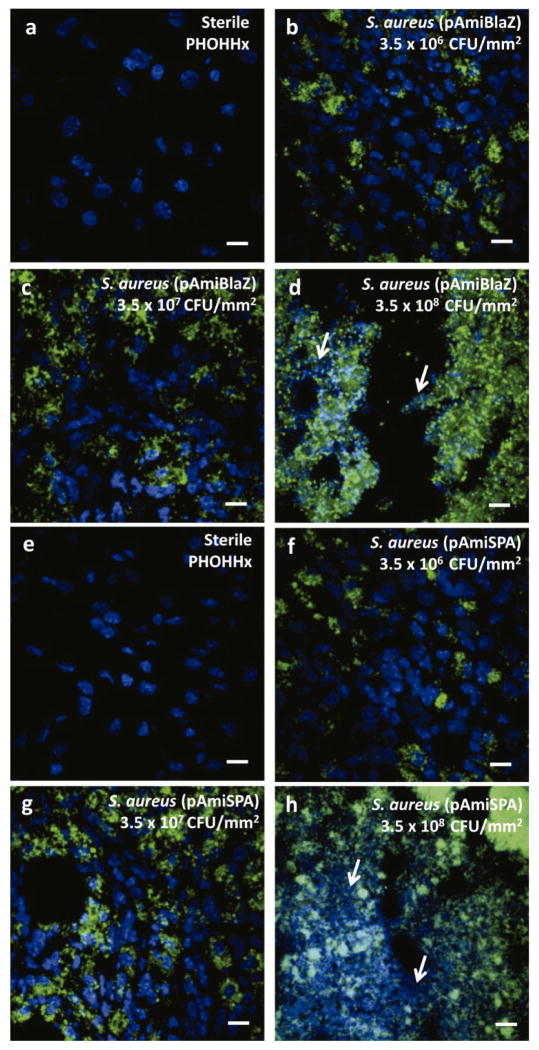

Sections were also stained for S. aureus using a commercial antibody. Grape-like clusters, characteristic for Staphylococcus species, stained positive for S. aureus were widely present in all samples that were pre-colonized by bacteria prior to implantation (Fig. 7). Bacterial cells were observed only in the vicinity on contaminated implants and not surrounding tissues (SFig. 1), demonstrating the pattern of localized infection. Additionally, initial signs of tissue damage around infected implants became evident with increasing number of bacteria used to pre-colonize disks. Tissue necrosis was present for inoculums of 3.5 × 108 CFU/mm2 or higher. DAPI-stained nuclei lost sharp borders and were completely destroyed (Fig. 7d,h). This phenomenon was observed only in the near vicinity of contaminated implant, whereas the cells of tissue located farther from the implant did not show signs of cell death (SFig. 1).

Figure 7.

Immunochemical staining for (a–d) S. aureus (pAmiBLAZ) and (f–g) S. aureus (pAmiSPA) in PHOHHx implant associated infection. (a,e) Sterile PHOHHx implant, (b,f) 3.5 × 106 CFU/mm2, (c,g) 3.5 × 107 CFU/mm2, and (d,h) 3.5 × 108 CFU/mm2. S. aureus marked with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated antibody shown in green, nucleus of cells surrounding implant DAPI stained and represented in blue. White arrows indicate zones of tissue necrosis. Scale bar 10 μm.

4. Discussion

Implantation of biomedical devices facilitates infection, since the biomaterial provides a surface for bacterial colonization and biofilm formation. Upon implantation, proteins and other biomacromolecules immediately coat the device and promote bacteria adhesion [24,25]. S. aureus harbors numerous cell wall-bound surface proteins that contain binding domains for mammalian proteins [26]. Early detection of these infections prior to formation of a recalcitrant biofilm is of great clinical importance. Hence, there is compelling need for the development of new sensitive diagnostic techniques for biomaterial-associated infections.

Conventional methodologies for monitoring pathogens in vivo are cumbersome and include biological assessment such as biopsies, biochemical and genetic testing. Therefore, we focused on developing a minimally-invasive imaging strategy for in vivo monitoring of bacterial infection on polymeric implants. In this study, we directly compared two imaging approaches: bacteria engineered to produce luciferase to generate bioluminescence and ROS imaging of the inflammatory response associated with the infected implant. Bioluminescent bacteria strains are widely used in the field to study the progression of a bacterial infection. We performed longitudinal imaging of bioluminescence associated with bacteria strains expressing luciferase plasmids driven by different promoters or a commercially available strain with the luciferase gene integrated into the chromosome. These luminescent strains provided excellent signal for acute (0–4 days) monitoring of the infection, but the bioluminescence signal decreased over time and leveled off by 7 days post-implantation (Fig. 2). We attribute this loss in bioluminescence signal primarily to changes in the metabolic activity of the bacteria. Because biofilm-associated bacteria mostly exist in a stationary phase-like state where transcription and translation are markedly reduced [4], we expect for luciferase expression to decrease as bacteria form biofilms. Notably, in one of the strains evaluated, luciferase was driven by the promoter of the spa2 gene responsible for expression of a S. aureus surface protein synthesized during biofim formation [20]. However, this construct did not increase the intensity of bioluminescence signal. Additionally, the decrease of number of bacteria carrying plasmid contributed to the loss of bioluminescence signal. The loss in bioluminescence signal was even observed when using a S. aureus strain carrying the lux operon stably integrated in the chromosome. In addition to the signal loss attributed to changes in metabolic activity in the bacteria, the intrinsic blue-green spectral output of lux (λmax = 425 nm) limited tissue penetration and the detection limit of this approach. Importantly, the magnitude and kinetics of luciferase expression were dependent on the specifics of the promoter and gene construct. Bioluminescence monitoring has been used as a tool to validate the efficiency of antibacterial treatment that implies short term screening [27,28]. Importantly, it has been reported that bioluminescence imaging could monitor chronic infection, but is strongly related to the infection model and bacterial strain used [29,30].

As an alternative to bioluminescence imaging of luciferase-expressing bacteria, we evaluated NIRF imaging of ROS generated by the inflammation associated with bacterial infection. NIRF imaging offers excellent characteristics for optical imaging enabling deeper tissue penetration and sensitivity [31]. Indeed, several NIRF probes for in vivo imaging of bacterial infections have been reported [32–38]. The sensing mechanism for these probes is based on metabolic conversion of probe inside bacteria or molecules with high affinity for bacterial membrane proteins. As discussed previously, the metabolic activity in many bacterial species vary among planktonic and biofilm states, therefore limiting the wide applicability of these probes. In addition, many of these probes have not been validated for imaging biofilm associated with a biomaterial. In contrast, we show that the ROS sensor H-ICG could provide sensitive and dose-dependent signals of biomaterial-associated bacteria. In addition, ROS imaging exhibited higher sensitivity than the bioluminescence imaging. Importantly, the ROS signal was independent of the bacteria strain (Fig. 4); this is a major advantage over bioluminescence imaging because it does not require the use of a luciferase-expressing bacteria strain. Additional characterization with other bacterial species and biomaterials is necessary to fully establish NIRF imaging of inflammatory responses as an effective strategy to monitor biomaterial-associated infections. Although the ROS signal for bacteria-colonized implants was significantly higher than the signal for sterile implants, the ROS probe would require calibration to discriminate between biofilm-containing and sterile implants, and this calibration may vary significantly due to variability among patient, device, implant location, and biofilm characteristics. Nevertheless, NIRF imaging of inflammatory responses represents a powerful alternative to bioluminescence imaging for monitoring biomaterial-associated bacterial infections in animal models.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Detection of PHOHHx implant associated infection by immunohistochemical staining for (a–d) S. aureus (pAmiBLAZ) and (f–g) S. aureus (pAmiSPA) in areas located distally from implant. (a,e) Sterile PHOHHx implant, (b,f) 3.5 × 106 CFU/mm2, (c,g) 3.5 × 107 CFU/mm2, and (d,h) 3.5 × 108 CFU/mm2. Scale bar 10 μm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Biópolis S.L. for the supplied polymer. This work was supported by the Ministerio of Economía y Competitividad (BIO2010-21049, 201120E092), the U.S.A. National Institutes of Health grant R21 AI094624 (A.J.G.), the Georgia Tech/Emory Center for the Engineering of Living Tissues, the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute under PHS Grant UL RR025008 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1422–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryers JD. Medical biofilms. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;100:1–18. doi: 10.1002/bit.21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiedrowski MR, Horswill AR. New approaches for treating staphylococcal biofilm infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1241:104–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lasa I. Towards the identification of the common features of bacterial biofilm development. Int Microbiol. 2006;9:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack D, Davies AP, Harris LG, Jeeves R, Pascoe B, Knobloch JK-M, Rohde H, Wilkinson TS. Staphylococcus epidermidis in Biomaterial-Associated Infection. In: Moriarty TF, Zaat SAJ, Busscher HJ, editors. Biomaterials Associated Infection. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 25–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjarnsholt T, Ciofu O, Molin S, Givskov M, Høiby N. Applying insights from biofilm biology to drug development - can a new approach be developed? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:791–808. doi: 10.1038/nrd4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auer JA, Goodship A, Arnoczky S, Pearce S, Price J, Claes L, von Rechenberg B, Hofmann-Amtenbrinck M, Schneider E, Müller-Terpitz R, Thiele F, Rippe KP, Grainger DW. Refining animal models in fracture research: seeking consensus in optimising both animal welfare and scientific validity for appropriate biomedical use. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle TC, Burns SM, Contag CH. In vivo bioluminescence imaging for integrated studies of infection. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:303–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaat SAJ. Tissue Colonization in Biomaterial-Associated Infection. In: Moriarty TF, Zaat SAJ, Busscher HJ, editors. Biomaterials Associated Infection. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 175–209. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson JM, Patel JD. Biomaterial-Dependent Characteristics of the Foreign Body Response and S. epidermidis Biofilm Interactions. In: Moriarty TF, Zaat SAJ, Busscher HJ, editors. Biomaterials Associated Infection. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 119–151. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selvam S, Kundu K, Templeman KL, Murthy N, García AJ. Minimally invasive, longitudinal monitoring of biomaterial-associated inflammation by fluorescence imaging. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7785–7792. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escapa IF, Morales V, Martino VP, Pollet E, Avérous L, García JL, Prieto MA. Disruption of β-oxidation pathway in Pseudomonas putida KT2442 to produce new functionalized PHAs with thioester groups. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:1583–1598. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furrer P, Panke S, Zinn M. Efficient recovery of low endotoxin medium-chain-length poly([R]-3-hydroxyalkanoate) from bacterial biomass. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;69:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FDA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FaDA, editor. Guideline on validation of the Limulus amebocyte lysate test as an end-product endotoxin test for human an animal parenteral drugs, biological products, and medical devices. Rockville, MD: 1987. http://www.gmpua.com/Validation/Method/LAL/FDAGuidelineForTheValidationA.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mesak LR, Yim G, Davies J. Improved lux reporters for use in Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid. 2009;61:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cucarella C, Solano C, Valle J, Amorena B, Lasa I, Penadés JR. Bap, a Staphylococcus aureus surface protein involved in biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2888–2896. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.9.2888-2896.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merino N, Toledo-Arana A, Vergara-Irigaray M, Valle J, Solano C, Calvo E, Lopez JA, Foster TJ, Penadés JR, Lasa I. Protein A-mediated multicellular behavior in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:832–43. doi: 10.1128/JB.01222-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Research Council; United States Department of Health and Human Services PHS, National Institutes of Health, editor. Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences. Bethesda, MD: National Research Council; 1985. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. NIH Publication No. 85-23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannan TJ, Mysorekar IU, Hung CS, Isaacson-Schmid ML, Hultgren SJ. Early severe inflammatory responses to uropathogenic E. coli predispose to chronic and recurrent urinary tract infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(8):e1001042. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001042.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420:846–852. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinjaski N, Fernández-Gutiérrez M, Selvam S, Parra-Ruiz FJ, Lehman SM, San Román J, García E, García JL, García AJ, Prieto MA. PHACOS, a functionalized bacterial polyester with bactericidal activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biomaterials. 2014;35:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francois P, Vaudaux P, Lew PD. Role of plasma and extracellular matrix proteins in the physiopathology of foreign body infections. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:34–40. doi: 10.1007/s100169900112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francois P, Schrenzel J, Stoerman-Chopard C, Favre H, Herrmann M, Foster TJ, Lew DP, Vaudaux P. Identification of plasma proteins adsorbed on hemodialysis tubing that promote Staphylococcus aureus adhesion. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:32–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(00)70018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster TJ, Hook M. Surface protein adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:484–488. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadurugamuwa JL, Sin LV, Yu J, Francis KP, Kimura R, Purchio T, Contag PR. Rapid direct method for monitoring antibiotics in a mouse model of bacterial biofilm infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3130–3137. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3130-3137.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keyaerts M, Caveliers V, Lahoutte T. Bioluminescence imaging: looking beyond the light. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai T, Tegos GP, Lu Z, Huang L, Zhiyentayev T, Franklin MJ, Baer DG, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii burn infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3929–3934. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00027-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waidmann MS, Bleichrodt FS, Laslo T, Riedel CU. Bacterial luciferase reporters: the Swiss army knife of molecular biology. Bioeng Bugs. 2011;2:8–16. doi: 10.4161/bbug.2.1.13566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilderbrand SA, Weissleder R. Near-infrared fluorescence: application to in vivo molecular imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leevy WM, Gammon ST, Jiang H, Johnson JR, Maxwell DJ, Jackson EN, Marquez M, Piwnica-Worms D, Smith BD. Optical imaging of bacterial infection in living mice using a fluorescent near-infrared molecular probe. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16476–16577. doi: 10.1021/ja0665592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bettegowda C, Foss CA, Cheong I, Wang Y, Diaz L, Agrawal N, Fox J, Dick J, Dang LH, Zhou S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Pomper MG. Imaging bacterial infections with radiolabeled 1-(2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodouracil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1145–1150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408861102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White AG, Gray BD, Pak KY, Smith BD. Deep-red fluorescent imaging probe for bacteria. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:2833–2836. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kong Y, Yao H, Ren H, Subbian S, Cirillo SL, Sacchettini JC, Rao J, Cirillo JD. Imaging tuberculosis with endogenous beta-lactamase reporter enzyme fluorescence in live mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12239–12244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000643107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leevy WM, Gammon ST, Johnson JR, Lampkins AJ, Jiang H, Marquez M, Piwnica-Worms D, Suckow MA, Smith BD. Noninvasive optical imaging of Staphylococcus aureus bacterial infection in living mice using a Bis-dipicolylamine-Zinc(II) affinity group conjugated to a near-infrared fluorophore. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:686–692. doi: 10.1021/bc700376v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piatkevich KD, Subach FV, Verkhusha VV. Far-red light photoactivatable near-infrared fluorescent proteins engineered from a bacterial phytochrome. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2153. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ning X, Lee S, Wang Z, Kim D, Stubblefield B, Gilbert E, Murthy N. Maltodextrin-based imaging probes detect bacteria in vivo with high sensitivity and specificity. Nat Mater. 2011;10:602–707. doi: 10.1038/nmat3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Detection of PHOHHx implant associated infection by immunohistochemical staining for (a–d) S. aureus (pAmiBLAZ) and (f–g) S. aureus (pAmiSPA) in areas located distally from implant. (a,e) Sterile PHOHHx implant, (b,f) 3.5 × 106 CFU/mm2, (c,g) 3.5 × 107 CFU/mm2, and (d,h) 3.5 × 108 CFU/mm2. Scale bar 10 μm.