Abstract

Purpose

To report change in strabismus-specific health-related quality of life (HRQOL) following treatment with prism.

Design

Retrospective cross-sectional study

Methods

Thirty-four patients with diplopia (median age 63, range 14 to 84 years) completed the Adult Strabismus-20 questionnaire (100 to 0, best to worst HRQOL) and a diplopia questionnaire in a clinical practice before prism and in prism correction. Before prism, diplopia was “sometimes” or worse for reading and/or straight ahead distance. Prism treatment success was defined as diplopia rated “never” or “rarely” on the Diplopia Questionnaire for reading and straight ahead distance. Failure was defined as worsening or no change in diplopia. For both successes and failures, mean Adult Strabismus -20 scores were compared pre-prism and in prism correction. Each of the four Adult Strabismus -20 domains (Self-perception, Interactions, Reading function and General function) were analyzed separately.

Results

Twenty-three (68%) of 34 were successes and 11 (32%) were failures. For successes, Reading Function improved from 57 ± 27 (SD) before prism to 69 ± 27 in-prism correction (difference 12 ± 20, 95% CI 3.2 to 20.8, P=0.02) and General Function improved from 66 ± 25 to 80 ± 18 (difference 14 ± 22, 95% CI 5.0 to 23.6, P=0.003). Self-perception and Interaction domains remained unchanged (P>0.2). For failures there was no significant change in Adult Strabismus -20 score on any domain (P>0.4).

Conclusions

Successful correction of diplopia with prism is associated with improvement in strabismus-specific HRQOL, specifically reading function and general function.

Introduction

Strabismus associated with diplopia significantly impacts an individual’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL).1–4 Previous studies have shown that successful surgical correction of strabismus is often associated with significant improvement in both function and psychosocial HRQOL concerns,4, 5 but there are few studies evaluating the effects of non-surgical treatments for strabismus on the patient’s HRQOL. Prism correction is a commonly used non-surgical treatment for binocular diplopia in the context of a variety of different strabismus types.6 Successful correction of diplopia using prism would be expected to result in significant improvements in visual function which may then translate into improved HRQOL. The aim of this study was to assess whether successful treatment of diplopia with prism was associated with improved HRQOL.

Subjects and Methods

This study is a retrospective cross-sectional study of patients with diplopia attending a clinical practice treated with prism. Approval was obtained prior to the commencement of the study from the Institutional Review Board, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN and all procedures and data collection were conducted in a manner compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Verbal consent and written HIPAA authorization were obtained for each patient.

Subjects

Consecutive strabismus patients undergoing prism correction of diplopia (using either Fresnel or incorporated prism) in a clinical practice were retrospectively reviewed. Eligible patients were those prescribed prism who had also completed the Adult Strabismus-20 questionnaire and the Diplopia Questionnaire at both their pre-prism examination and at their follow-up examination when wearing prism correction. Both the Adult Strabismus -20 and the Diplopia Questionnaire were administered routinely to all patients with diplopia, at each examination, from March 2010. Unwillingness or refusal to complete the questionnaires was extremely rare, minimizing patient selection bias. Patients prescribed prism for blur, asthenopia or eyestrain who did not also report symptoms of diplopia on the Diplopia Questionnaire were not eligible for inclusion, neither were patients who were already wearing a prism correction. Response to prism treatment was assessed at a follow-up examination at least 3 weeks after prism correction was prescribed.

Methods

Diplopia questionnaire

The Diplopia Questionnaire 7 (freely available at: www.pedig.net, accessed December 16th, 2013) was completed by each patient as part of their clinical examination, typically while the patient was in the waiting area and before any clinical testing commenced. The Diplopia Questionnaire allows the patient to rate the severity of their diplopia in each of 7 gaze positions (reading, straight ahead distance, right gaze, left gaze, up gaze, down gaze and any other gaze position) on a 5-point scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always).

For inclusion in the present study of responsiveness to prism correction, diplopia prior to prescribing prism was required to be at least moderately severe, defined as the patient rating diplopia frequency as either “sometimes” or worse for reading and/or for straight ahead distance on the Diplopia Questionnaire. This requirement allowed room for improvement defined as reduction in diplopia frequency to “rarely” or “never.”

Adult Strabismus-20 questionnaire

The Adult Strabismus-20 is a patient-derived, strabismus-specific HRQOL questionnaire for adults with strabismus.2, 4 Patients typically completed the Adult Strabismus-20 in the waiting area before the commencement of any clinical testing. In previous Rasch analysis of the Adult Strabismus-20,8 four distinct domains were identified: Self-perception (5 items), Interactions (5 items), Reading Function (4 items) and General Function (4 items) (full questionnaire freely available at: www.pedig.net, accessed February 3rd, 2014). Each of the four domains is scored independently using Rasch scoring methods, and converted to a 0 to 100 score (worst to best HRQOL) for easier interpretation (scoring spreadsheet freely available at: www.pedig.net, accessed February 3rd, 2014).

Analysis

Prism success and failure

Prism treatment success was defined as diplopia while wearing prism, rated as “never” or “rarely” for both reading and for straight ahead distance. Prism treatment failure was defined as worsening or no change in diplopia for reading and/or straight ahead distance.

Adult Strabismus-20 scores

Mean Adult Strabismus-20 scores (0 to 100, worst to best HRQOL) were calculated, both before prism correction and when wearing prism correction, for each of the four Adult Strabismus-20 domains (Self-perception, Interactions, Reading Function and General Function) in each patient. Before prism data were taken from the visit at which prism was first prescribed. In prism data were taken from the next examination, regardless of whether prism strength was subsequently changed or not.

Adult Strabismus-20 scores before prism correction and when wearing prism were compared overall, and in sub-groups of successes and failures, using signed rank tests. In addition, Adult Strabismus-20 scores before prism correction and in prism were compared between Fresnel prism and ground-in prism for successes and failures using Wilcoxon tests.

To evaluate for potential baseline differences between patients who ended up as successes and those who ended up as failures, several factors were compared between groups. Mean Adult-Strabismus-20 scores and mean Diplopia Questionnaire scores before prism, were compared between success and failures using Wilcoxon tests. Median prism strength prescribed was also compared between success and failures using Wilcoxon tests. In addition, the proportion of patients with incommitant deviations was compared between groups using Fisher’s exact tests: incommitance was defined as a difference between primary position and up, down, right or left gaze of 10 PD or more for horizontal deviation or 5 PD or more for vertical deviation.

Results

Thirty-four patients (median age 63, range 14 to 84 years) were included. Twenty-four (71%) were female and for 33 (97%) race was reported as White. Strabismus types were: Idiopathic (11/34, 32%), Childhood onset (7/34, 21%), Mechanical (7/34, 21%) and Neurogenic (9/34, 26%). Twenty four (71%) of 34 had undergone previous strabismus surgery, 9 (38%) having had surgery within the previous 3 months, but only 3 of these were prescribed prism due to worse diplopia following surgery. No patient was prescribed prism for postoperative diplopia when there had been no diplopia preoperatively. Overall the mean magnitude of prism prescribed was 8 prism diopters (PD), ranging from 1PD to 25PD. Twenty-three (68%) of 34 patients were prescribed Fresnel prism and 11 (32%) were prescribed ground-in prism. Follow-up examinations in prism correction were a mean of 4.5 months (range 3 weeks to 18 months) following the pre-prism examination.

Indications for prism correction were either long-term management of diplopia associated with small angle (defined as 10 PD or less) strabismus (n=19, 56%), temporary correction of diplopia prior to strabismus surgery (n=9, 26%), long-term management of diplopia in patients for whom strabismus surgery was presently inadvisable e.g. evolving Graves’ disease, resolving 6th cranial nerve palsy (n=5, 15%), near-distance disparity where different prisms were needed for near and distance fixation (n=1, 3%).

Based on a priori definitions of success and failure using responses on the Diplopia Questionnaire, 23 (68%) of 34 patients were classified as prism successes and 11 (32%) were classified as prism failures.

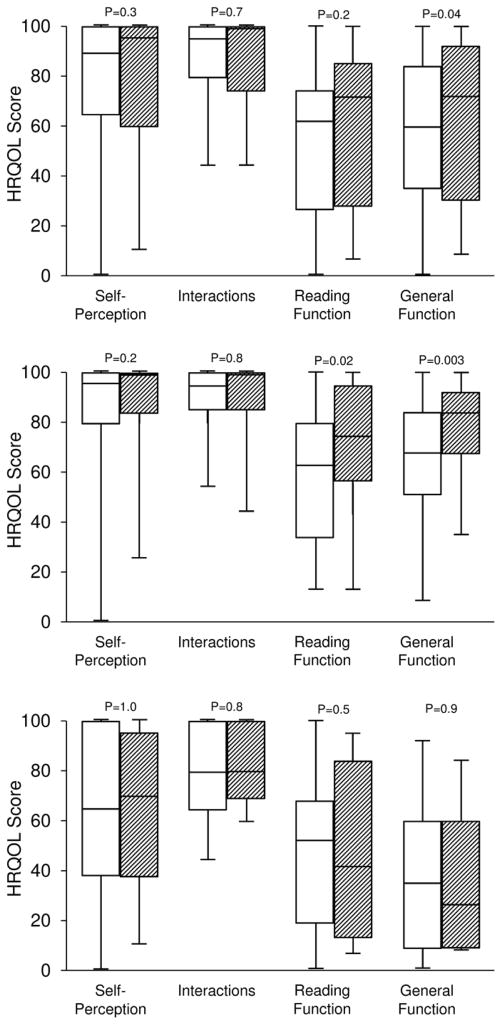

Adult Strabismus-20 scores before prism: all patients

Overall mean Adult Strabismus-20 scores before prism were 57 ± 29 (SD) for the General Function domain, 54 ± 28 for the Reading Function domain, 79 ± 26 for the Self-perception domain and 87 ± 16 for Interactions (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Box and whisker plots of Adult Strabismus-20 Health Related Quality of Life scores in patients with diplopia treated with prism. Clear boxes show pre-prism scores and shaded boxes show scores in prism correction. Center line represents the median, top and bottom of the boxes upper and lower quartiles, whiskers extremes. Top (A): All patients; Center (B): Successfully treated patients only; Bottom (C): Patients who failed prism treatment.

Adult Strabismus-20 scores in prism: all patients

Across all patients, mean Adult Strabismus-20 scores when wearing prism were significantly improved for the General Function domain compared with scores before prism correction, improving from 57 ± 29 to 66 ± 29 (mean difference 9 ± 27, 95% CI −0.1 to 19.0; P=0.04, Figure 1A). For the Reading Function, Self-perception and Interaction domains, there were no significant changes in scores from before prism correction to wearing prism (P>0.1 for each, Figure 1A).

Adult Strabismus-20 scores in prism: successes

For the 23 patients successfully treated with prism, mean Adult Strabismus-20 scores significantly improved when wearing prism for the General Function and Reading Function domains. For General Function, scores improved from 66 ± 25 before prism correction to 80 ±18 in prism correction (mean difference 14 ± 22, 95% CI 5.0 to 23.6, P=0.003, Figure 1B) For the Reading Function domain scores improved from 57 ± 27 before prism correction to 69 ± 27 in prism correction (mean difference 12 ± 20, 95% CI 3.2 to 20.8; P=0.02, Figure 1B). For Self-perception and Interaction domains, there was no difference between HRQOL scores before prism correction and when wearing prism correction (P>0.2 for each, Figure 1B).

Adult Strabismus-20 scores in prism: failures

For the 11 patients for whom prism treatment was unsuccessful, there were no significant differences between Adult Strabismus-20 scores before prism correction and Adult Strabismus-20 scores when wearing prism correction, for each of the four Adult Strabismus-20 domains (P>0.4 for each, Figure 1C).

Fresnel versus ground-in prism

Of the 23 patients successfully treated with prism, 17 (74%) were treated with Fresnel prism and 6 (26%) with ground-in prism. Of the 11 patients who failed prism treatment, 6 (55%) were treated with Fresnel prism and 5 (45%) with ground-in prism. For successfully treated patients Adult Strabismus-20 scores improved on the Reading function domain both for patients wearing Fresnel prism (mean 58 ± 26 to 71 ±25; mean difference 13 ± 23, 95% CI 0.8 to 24.9; P=0.05) and for patients wearing ground-in prism (mean 55 ± 33 to 64 ± 36; difference 10 ± 7, 95% CI 1.9 to 17.2; P=0.06). For the General Function domain, scores improved for patients treated with Fresnel prism (mean 61 ± 26 to 80 ± 18; difference 19 ± 22, 95% CI 7.9 to 30.9; P=0.002) but did not significantly improve for patients wearing ground-in prism (mean 80 ± 14 to 80 ± 20; difference −1 ± 10, 95% CI −10.7 to 10.7; P=1.0). For the Self-perception and Interactions domains, there were no improvements in scores for patients treated with Fresnel prism (P>0.3 for each) or ground-in prism (P>0.6 for each). For failures, on the General Function domain, scores numerically improved for patients wearing Fresnel (20 ± 19 to 44 ± 22; difference 24 ± 23, 95% CI −0.3 to 48.2, P=0.1) and reduced for patients wearing ground in prism (mean 59 ± 25 to 29 ± 32; difference −30 ± 23, 95% CI −58.6 to −2.2, P=0.06), however differences were not statistically significant. There were no differences in Adult Strabismus-20 scores for Fresnel prism or ground in prism on any of the other three Adult Strabismus -20 domains (P>0.06 for all)

Baseline differences between successes and failures

Adult Strabismus-20 scores before prism

For the General Function domain of the Adult Strabismus -20, scores before prism correction were significantly higher (better) for the 23 successes than for the 11 failures (66 ± 25 vs 38 ± 29; P=0.01). For the other three Adult Strabismus -20 domains, scores before prism correction were not significantly different between successes and failures (P>0.08 for each).

Diplopia scores before prism

Comparing baseline diplopia questionnaire scores between successes and failures, there was no significant difference between scores for the 23 prism successes (mean diplopia score 58 ± 24) and scores for the 11 prism failures (mean diplopia score 58 ± 28, P=1.0).

Magnitude of prism prescribed

The magnitude of prism prescribed was similar for successes (6 PD, range 1PD to 25PD) and failures (10PD, range 2PD to 20PD; P=0.3).

Incomitant strabismus

Overall, 25 (74%) of 34 patients were classified as having comitant strabismus and 9 (26%) as incomitant strabismus. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with incomitant deviations in those successfully treated with prism compared with those for whom prism treatment failed: of the 23 successes, 6 (26%) had incomitant deviations and of the 11 failures, 3 (27%) had incomitant deviations (P=1.0).

Discussion

In this study of prism correction of binocular diplopia we found that successful treatment was associated with improved HRQOL whereas there was no improvement in HRQOL with unsuccessful treatment. In successfully treated patients HRQOL improvements were confined to the function domains of the Adult Strabismus -20 questionnaire (Reading Function and General Function) with no changes on the psychosocial domains.

The findings of this present study confirm the common clinical experience that many patients report symptomatic relief and improved vision-related HRQOL with successful prism correction of their diplopia. By using the diplopia questionnaire for patient rating of diplopia frequency and the Adult Strabismus 20 questionnaire to quantify HRQOL concerns, such improvements can be verified and quantified, confirming a valuable role for prism in the management of diplopia. The lack of HRQOL improvement in patients classified as prism treatment failures suggests that our finding of HRQOL improvement in successfully treated patients was not attributable to a placebo effect.

There are few previous studies evaluating HRQOL in patients undergoing prismatic correction of diplopia using prism. Tamhankar et al6, 9 reported success with prism treatment across a variety of different strabismus types, but did not specifically evaluate related effects on HRQOL. In studies of other (non-prism) treatments for strabismus, HRQOL has been shown to improve following surgical correction4 as well as in small-angle diplopic strabismus treated with monovision correction.10 We now report improvements in HRQOL in strabismus patients whose diplopia was successfully treated using prism.

In this present study of adults with a diverse range of strabismus types and moderately severe diplopia, we found a prism success rate of 68%. In two previous studies of prism treatment for diplopia, Tamhankar et al reported success rates in adult strabismus patients.6, 9 For both Tamhankar et al studies, success with prism was defined as complete or partial resolution of diplopia based on patient report. In the first study, of 94 patients with a range of motility disorders, 88% were considered successfully treated6 and in the other study, of 64 patients with large angle, incomitant, or combined horizontal and vertical strabismus, 72% were successfully treated.9 Using quantitative methods of assessing diplopia using the Diplopia Questionnaire, our success rate of 68% compares favorably with these previous studies.

To address the possibility of a placebo effect from simply wearing the prism we dichotomized prism treatment outcomes into success and failure using a standardized measure of diplopia frequency. Our finding of no improvement in HRQOL in those objectively categorized as prism treatment failures strongly suggests that improvements in HRQOL can be directly attributed to successful prism correction of diplopia. These differences in HRQOL scores between prism success and prism failures also provide further evidence of the discriminative validity of the Adult Strabismus -20 questionnaire.

We speculated that the characteristics of patients undergoing successful prism treatment may be different to those who failed prism treatment. Specifically we evaluated pre-prism Adult Strabismus-20 scores, severity of pre-prism diplopia, magnitude of prism prescribed, and presence of incomitance. Patients who ended up failing prism treatment had poorer function-related HRQOL before prism correction than those who ended up being successfully treated. Interestingly there were no differences between successes and failures regarding pre-prism diplopia severity, magnitude of prism or incomitance. Poorer HRQOL scores before prism correction, in the absence of worse diplopia or incommitant strabismus, may be attributable to factors not measured in this study. For example, a previous study has shown that depression can reduce HRQOL (Hatt SR, et al. IOVS 2013;54:ARVO E-Abstract 5987). Due to the small number of patients in this study, we did not perform logistic regression analysis to determine which factors were most predictive of prism failure or success.

There are several limitations to this study. We studied a relatively small number of patients which may have precluded finding differences in clinical characteristics between prism successes and prism failures. In addition, in order to be able to measure improvements in diplopia with prism correction we limited our study to patients with moderately severe diplopia. While this requirement represents the majority of patients offered prism correction, some patients have less severe diplopia and our findings are not necessarily generalizable to this population. It is also possible that our cohort does not adequately represent response to prism in patients with larger angles of deviation as these are more likely to go to surgery without a trial of prism. Finally, it may be that advice given to the patient regarding the likely success of prism correction and the possible duration of prism wear may have influenced their expectations and thus their subsequent HRQOL, but unfortunately these data were not available in the medical record.

Successful prism correction of diplopia is associated with improved function-related HRQOL. Prism correction of diplopia provides a valuable non-surgical treatment option and may be especially beneficial in patients with small angle strabismus.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant EY018810 (JMH), Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY (JMH as Olga Keith Weiss Scholar and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic), and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN.

Other Acknowledgments: None.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: No authors have any financial/conflicting interests to disclose.

Contributions to Authors in each of these areas: design and conduct of the study (SRH, DAL, LL, JMH); collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data (SRH, DAL, LL, JMH); preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript (SRH, DAL, LL, JMH).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Kirgis PA, Bradley EA, Holmes JM. The effects of strabismus on quality of life in adults. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(5):643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Bradley EA, Cole SR, Holmes JM. Development of a quality-of-life questionnaire for adults with strabismus. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Bradley EA, Cole SR, Holmes JM. Comparison of quality of life instruments in adults with strabismus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(4):558–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Holmes JM. Responsiveness of health-related quality of life questionnaires in adults undergoing strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(12):2322–2328. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Liebermann L, Holmes JM. Changes in health-related quality of life 1 year following strabismus surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(4):614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamhankar MA, Ying GS, Volpe NJ. Effectiveness of prisms in the management of diplopia in patients due to diverse etiologies. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49(4):222–228. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20120221-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes JM, Liebermann L, Hatt SR, Smith SJ, Leske DA. Quantifying diplopia with a questionnaire. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1492–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leske DA, Hatt SR, Liebermann L, Holmes JM. Evaluation of the Adult Strabismus-20 (AS-20) Questionnaire using Rasch analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(6):2630–2639. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamhankar MA, Ying GS, Volpe NJ. Prisms are effective in resolving diplopia from incomitant, large, and combined strabismus. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012;22(6):890–897. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bujak MC, Leung AK, Kisilevsky M, Margolin E. Monovision correction for small-angle diplopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(3):586–592. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]