Abstract

Proanthocyanidin (PAC) rich plant-derived agents have been shown to enhance dentin biomechanical properties and resistance to collagenase degradation. This study systematically investigated the interaction of chemically well-defined monomeric catechins with dentin extracellular matrix components by evaluating dentin mechanical properties as well as activities of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cysteine-cathepsins (CTs). Demineralized dentin beams (n = 15) were incubated for 1 hr with 0.65% (+)-catechin (C), (−)-catechin gallate (CG), (−)-gallocatechin gallate (GCG), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), and (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG). Modulus of elasticity (E) and E fold increase were determined, comparing specimens at baseline and after treatment. Biodegradation rates were assessed by differences in percentage of dry mass before and after incubation with bacterial collagenase. The inhibition of MMP-9 and CT-B by 0.65%, 0.065% and 0.0065% of each catechin was determined using fluorimetric proteolytic assay kits. All monomeric catechins led to a significant increase in E. EGCG showed the highest E fold increase, followed by ECG, CG and GCG. EGCG, ECG, GCG and CG significantly lowered biodegradation rates and inhibited both MMP-9 and CT-B at a concentration of 0.65%. Overall, the 3-O-galloylated monomeric catechins are clearly more potent than their non-galloylated analogues in improving dentin mechanical properties, stabilizing collagen against proteolytic degradation, and inhibiting the activity of MMPs and CTs. The results indicate that galloylation is a key pharmacophore in the monomeric and likely also in the oligomeric PACs that exhibit high cross-linking potential for dentin extracellular matrix.

Keywords: proanthocyanidins, cross-linking, collagen, MMP, cysteine-cathepsins

1. Introduction

Plant extracts rich in polyphenols have shown pronounced bioactivity with cellular and extracellular matrix components and promising applications in many disease processes. In particular, proanthocyanidin (PAC) rich sources have demonstrated application in the dental field for enhancement of dentin biomechanical properties and its biostability [1,2]. While a strong correlation between the degree of polymerization of oligomeric PACs (OPACs) and an increased modulus of elasticity of the dentin matrix has been demonstrated, the protective effect against bacterial collagenase greatly increases regardless of the fingerprint composition of the PAC plant source [3]. Due to the highly diverse composition of monomeric and oligomeric PACs in the different plant taxa and the associated analytical complexity, their use as standardized intervention material is still limited. While lower molecular weight compounds (up to trimers) are available commercially, albeit in very limited quantities for non-monomers, the isolation and standardization of OPACs still represent a challenge and require development of separation and other analytical techniques, specifically for the higher molecular weight bioactive compounds.

The OPACs represent renewable and sustainable resources composed of flavan-3-ol building blocks, which are characterized by a saturated C-ring and a hydroxylation in position C-3. The monomeric PAC moieties, named catechins, are abundant in green and white tea, while their dimeric, trimeric and higher oligomeric forms (OPACs) are more abundant in grape seed, pine barks, cocoa and other plant products [3-5]. Catechins can be classified according to their stereochemistry, the different substituents in the B ring, as well as the presence or absence of 3-O-galloylation. Notably, OPACs can contain two different “gallo” motifs: in the catechin gallates, a gallic acid moiety esterifies the C-3-OH group of the catechin moiety; in gallocatechins, the B-ring of the catechin moiety bears the same 3,4,5-trihydroxy substitution as gallic acid. Variations in the chemical structure of catechins affect their binding affinity with proteins [6]. Galloylated catechins have shown better potential benefits (antiproliferative, apoptotic and antioxidant) as anticancer agents when compared to other monomeric catechins [7,8]. Although it has been proposed that galloylated catechins can stabilize collagen by hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds [9,10], the dentin model herein explored specifically addressed the interactions of monomeric compounds to an already innately highly cross-linked collagen structure. In addition, the dentin matrix contains non-collagenous proteins and endogenous proteases, providing a dynamic system for the study of polyphenols on extracellular matrix.

The aim of the present study was to determine the interactions of the monomeric catechins with dentin matrix components (type I collagen, MMPs and CTs) and their effects on mechanical properties and biostability. The hypotheses tested were the following: 1) the modulus of elasticity and the collagen resistance to degradation of dentin varies when treated with the different monomeric catechins; and 2) the activities of recombinant MMPs and CTs are inhibited to a different extent by the various monomeric catechins.

2. Materials and Methods

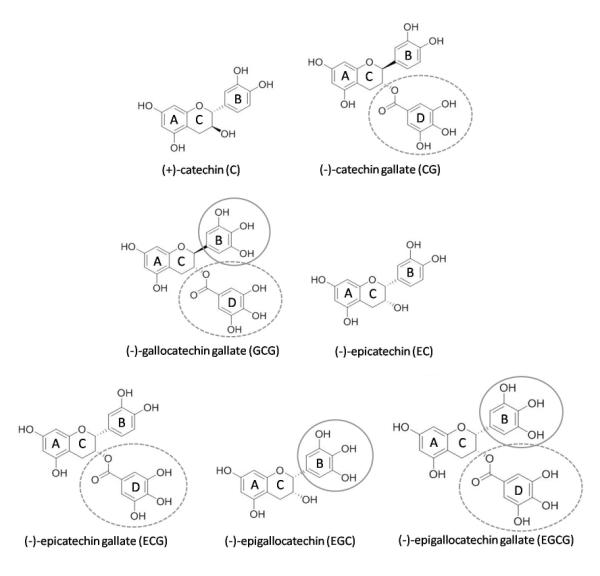

The monomeric catechins C, CG, GCG, EC, ECG, EGC and EGCG were obtained commercially (C from Indofine Chemical Company, Inc., Hillsborough, NJ, USA; the others from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and were comprehensively characterized by NMR, MS and LC analysis [11]. Force field calculations (MM2) were performed using ChemBioDraw® (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The chemical structure of all monomeric catechins used is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the monomeric catechins. The two aromatic rings of the core are assigned as A- and B-ring, while the C-ring is a dihydropyrane heterocycle. The circles show the gallo substitution patterns of the B-ring (full circle) and the galloyl moieties attached to C-3-OH (dashed circle).

2.1. Sample preparation

Twenty-five intact human molars were selected following a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois at Chicago (#2011-0312). Specimens were obtained from mid-coronal dentin and cut in a slow speed diamond saw under water lubrication (Isomet, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL) as previously described [1]. The dentin beams were demineralized in 10% phosphoric acid (Ricca Chemical Company, Arlington, TX, USA) for 5 hrs [12]. Demineralized dentin beams were randomly divided into 8 groups (n = 15) and treated with 0.65% (w/v) C, CG, GCG, EC, ECG, EGC and EGCG dissolved in 0.02 M HEPES (pH 7.2) for 1 hr at room temperature. Control group was incubated with HEPES buffer under the same experimental conditions. Solutions of GCG and EGC presented a pale pink color. However, even after 1 hour of incubation, no major alterations in the color of the dentin beams were observed. The solutions of all other compounds were colorless.

2.2. Biomechanical analysis – Apparent Modulus of Elasticity

Dentin beams were tested in a three-point bending assay as previously described [13] using a 1 N load cell mounted on a universal testing machine (EZ Graph, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min. The apparent modulus of elasticity (E) was determined at baseline and after 1 hr exposure to catechins using the following formula: E = PL3/4DbT3, where P is the maximum load, L is the support span, D is the displacement, b is the width of the specimen and T is the thickness of the specimen. The fold increase in E before and after treatment was also calculated. Data were analyzed by two-way and one-way ANOVA and Games-Howell post hoc tests (α = 0.05).

2.3. Dentin biodegradation – bacterial collagenase

Dentin biodegradation was assessed by its resistance to bacterial collagenase digestion. After the exposure to catechins and biomechanical analysis, the same specimens were dried in a vacuum desiccator containing anhydrous calcium sulfate for 24 hrs at room temperature and the mass (M1) was obtained on an analytical balance (XS105DU, Mettler Toledo Inc., Columbus, OH, USA). Then, beams were re-hydrated in distilled water for 1 hr and incubated with type I bacterial collagenase (100 μg/ml C. histolyticum) (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.2 M ammonium bicarbonate pH 7.9 at 37 °C for 24 hrs under constant agitation (160 rpm). After digestion, beams were washed, dried as described before and the final mass (M2) was obtained. Dentin biodegradation rates (R) were determined by the following formula: R (%) = 100 – (M2×100)/M1; where M1 is the biomodified dentin matrix dry mass and M2 is the dry mass after bacterial collagenase digestion. Data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Games-Howell post hoc tests (α = 0.05).

2.4. Inhibition of Proteases

A recombinant human enzyme MMP-9 (Anaspec Inc., Freemont, CA), a generic MMP assay kit (SensoLyte® 520 generic MMP assay kit fluorimetric, Anaspec Inc.) and a CT-B assay kit (SensoLyte® 440 cathepsin B assay kit fluorimetric, Anaspec Inc.) were selected to evaluate the inhibition of MMPs and CTs by the catechins. Assays were performed in 96-well microplates. The recombinant enzymes were pre-incubated with 0.65%, 0.065% and 0.0065% C, CG, GCG, EC, ECG, EGC and EGCG, individually, for 15 min at room temperature before adding the substrates. The positive control groups were MMP-9 and CT-B only, without catechins, while the negative controls were MMP-9 incubated with EDTA (2 mM), a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor, and CT-B incubated with 1 μM Ac-LVK-CHO, the inhibitor supplied in the kit. The fluorescence was read at baseline, after 4 and 24 hrs of incubation in triplicate with microplate readers using Ex/Em = 490 nm/520 nm (Synergy 2 BioTek, Winooski, VT, US) for MMP-9 and Ex/Em = 354 nm/442 nm for CT-B (VictorTM X5, PerkinElmer Inc., Downers Grove, IL, US). Fluorescence at the different time points was determined by subtracting background fluorescence and was expressed in arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU). Activity was expressed in percentage of inhibition according to the positive control groups activity after 4 hrs of incubation. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way and one way ANOVA and Games Howell post hoc tests (α = 0.05).

3. Results

The two-way ANOVA test depicted statistically significant difference in E between groups before and after treatment with catechins (p < 0.001) and among the different catechins (p < 0.001). Dentin treated with CG, GCG, ECG and EGCG presented significantly higher E than that treated with C, EC and EGC. These last three groups showed no statistical difference when compared to the control group (Table 1). Significant differences among catechins were observed for E fold increase (p < 0.001). The highest results were observed for EGCG, followed by ECG, CG and GCG. C, EC and EGC showed fold increase similar to the control group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the apparent modulus of elasticity (E), E fold increase and resistance to collagenase digestion after treatment with 0.65% catechins for 1 hour. Mean (standard deviation) (n = 15).

| Group | Modulus of Elasticity (E) (MPa) | Fold Increase | Biodegradation rates (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After treatment | |||

| Control | 4.24 (0.99)A, B | 5.61 (2.01)B | 1.35 (0.42)D | 75.29 (16.40)D |

| C | 3.66 (1.19)A,B | 6.56 (1.92)B | 1.83 (0.34)C | 50.48 (18.76)C |

| CG | 5.05 (1.59)A | 21.93 (6.02)A | 4.54 (1.12)B | 12.57 (3.10)A |

| GCG | 5.07 (1.36)A | 22.63 (8.90)A | 4.43 (0.95)B | 10.15 (3.18)A |

| EC | 3.53 (1.36)A, B | 5.42 (1.75)B | 1.58 (0.36)C, D | 62.17 (17.76)C, D |

| ECG | 3.56 (1.21)A, B | 16.58 (4.10)A | 4.93 (1.19)B | 7.36 (5.54)A |

| EGC | 3.34 (0.58)B | 6.07 (1.97)B | 1.80 (0.41)C, D | 27.75 (12.44)B |

| EGCG | 3.37 (0.92)B | 21.47 (5.53)A | 6.52 (1.14)A | 7.01 (5.71)A |

C: (+)-catechin, CG: (−)-catechin gallate, GCG: (−)-gallocatechin gallate, EC: (−)-epicatechin, ECG: (−)-epicatechin gallate, EGC: (−)-epigallocatechin, and EGCG: (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. All groups showed significant increase in E after biomodification when compared to baseline (p < 0.001). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups (columns) (p < 0.05).

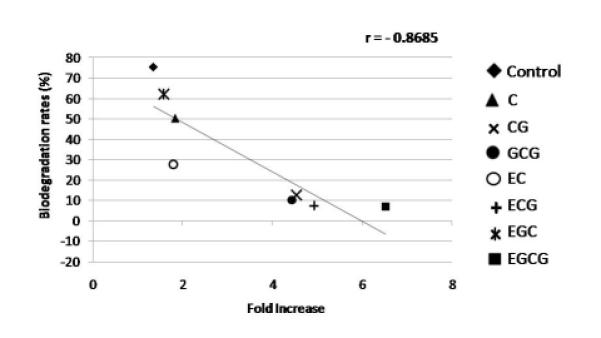

Statistically significant lower biodegradation rates were observed for EGCG, ECG, GCG and CG, followed by EGC and C. There was no significant difference between EC and control (Table 1). A very strong negative correlation was observed between fold increase and biodegradation rates (Figure 2) (p = 0.005).

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation coefficient (r) comparing fold increase and biodegradation rates (%) observed for all monomeric catechins.

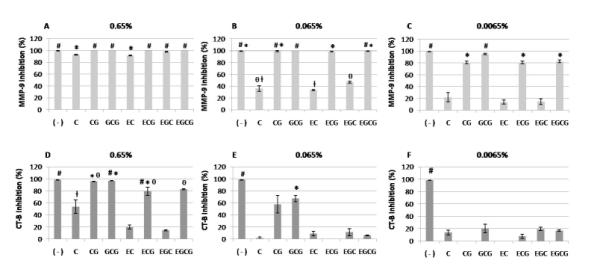

The inhibition of proteases by each catechin is presented in Figure 3. Both MMP-9 and CT-B showed decrease in activity when pre-treated with catechins from baseline up to 24 hrs (data not shown). At 4 hrs of incubation, two-way ANOVA showed statistically significant differences between monomeric catechins and their concentrations, for both MMP-9 and CT-B (p < 0.001). The results of inhibition of MMP-9 demonstrated differences between the catechins (p < 0.001); however, the inhibition pattern was concentration dependent. All catechins showed decrease in MMP-9 activity at 0.65% and 0.065% (Figure 3A and 3B). On the other hand, at 0.0065%, only CG, GCG, ECG and EGCG were able to inhibit MMP-9 (Figure 3C). Regardless of the concentration, galloylated catechins showed more than 80% of inhibition of MMP-9. The effects on CT-B activity were different for all catechins at any concentration (p < 0.001), however significant inhibition was observed for most only at 0.65% (Figure 3D). CT-B was not inhibited by EC and EGC.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of proteases (%) after incubation with different concentrations of each catechin (after 4 hrs of incubation). A: inhibition of MMP-9 by 0.65% catechins; B: inhibition of MMP-9 by 0.065% catechins; C: inhibition of MMP-9 by 0.0065% catechins; D: inhibition of CT-B by 0.65% catechins; E: inhibition of CT-B by 0.065% catechins; F: inhibition of CT-B by 0.0065% catechins. ( − ): negative control group (inhibitor), C: (+)-catechin, CG: (−)-catechin gallate, GCG: (−)-gallocatechin gallate, EC: (−)-epicatechin, ECG: (−)-epicatechin gallate, EGC: (−)-epigallocatechin, and EGCG: (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Bars with symbols show statistical significant differences when compared to positive control groups (MMP-9 and CT-B) (p < 0.05). Different symbols indicate statistical significant differences between catechins (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The present study determined the effectiveness of all important monomeric catechins, which are typically present in polyphenol-rich extracts, and contributes to a better understanding of their interaction with different extracellular matrix components. It was observed that monomeric catechins with galloyl moieties most effectively increase the modulus of elasticity and reduce collagen biodegradation rates. At the same time, MMP-9 activity showed significant reduction for all concentrations when incubated with galloylated catechins. The same effect was observed for CT-B at high concentration. Therefore, both tested hypotheses were confirmed.

While gallocatechin (GC) could not be obtained in sufficient amounts for this study, the structure activity relationships evident from the present data indicate that GC would likely not add further insights. In addition, GC is mostly a very minor constituent in plant extracts. CG-, GCG-, ECG- and EGCG-treated dentin showed significantly high modulus of elasticity and reduced biodegradation rates, and the highest E fold increase was obtained by EGCG. Moreover, a significant correlation was observed for fold increased and biodegradation rates. Overall, this reveals that the increase in collagen stabilization depends on the specific chemical structures of the monomeric compounds. The stabilization of solubilized collagen by catechins has previously been suggested by indirect methods [14]. However, the present study shows the effect of catechins in the modification of the dentin matrix, leading to the formation of cross-links in an already highly cross-linked structure.

All catechins contain phenolic hydroxyl groups, which can interact with various proteins by forming multiple hydrogen bonds. It has been demonstrated that hydrogen bonds play an important role in collagen stabilization by PACs [15]. CG, GCG, ECG, and EGCG all have a greater hydrogen bonding capability than the other catechins due to the presence of three vicinal hydroxyl groups from the galloyl moiety (Figure 1). This might explain the significant increase in E and E fold increase observed in the present study. The hypothesis of more hydroxyl groups forming more hydrogen bonds is supported by the highest E fold increase observed for EGCG. The hydrogen bonds formed by EGCG and collagen could stabilize the collagen backbone in a similar way to that proposed for sugars [16].

While the monomers, GCG and EGCG, have identical planar structures, they differ in stereochemistry and constitute a C-3 epimeric pair (Figure 1). Their MM2 force field optimized 3D structures are represented in Figure 4, showing that in GCG, the A- and C-rings are in a near orthogonal position to the B- and D-rings, which are parallel to each other and can potentially interact via π-stacking. Due to the C-3 epimerism, the B- and D-rings assume anti-parallel orientation in the majority of the EGCG conformers, thus exhibiting an increased distance between the gallo B-ring and the gallic acid D-ring. These differences have also been highlighted in a recent study [8], albeit by reversing the assignment of the epimeric pair GCG and EGCG. While it is likely that these stereochemical structural features impact the collagen cross-linking ability of the monomeric catechins, it remains speculative to conclude that the B- and D-ring positions in EGCG could possibly explain the higher ability to form cross-links between more distant collagen microfibrils. Solution conformation studies on physiologic media and, more importantly, structural studies of monomers bound to dentin will be necessary to address these questions. Until then, the results from the present study allow the conclusion that EGCG is the most potent monomeric catechin with dentin cross-linking ability.

Figure 4.

Comparison of MM2 force field minimized three-dimensional structures of the galloylated catechin, (−)-gallocatechin gallate (GCG), and its C-3 epimer, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), shows the impact of the epimerism on the overall molecular shape. While GCG conformers are potentially stabilized via intramolecular π-stacking, the B- and D-rings in EGCG are anti-parallel.

Moreover, while CG, GCG, ECG and EGCG contain a galloyl moiety attached to the C-ring, the epimers GCG and EGCG contain an extra hydroxyl group on the B-ring due to their gallo type substitution (Figure 1). Our results show that the presence of a gallate moiety attached to carbon C-3 of the C-ring is more important for the dentin bioactivity of catechins than gallo-type substitution in the B-ring. Interestingly, the same pattern was reported for their antioxidant and proapoptotic effects in cancer cells [7]. In addition, the collagen amino acids composition might influence its interaction with catechins. Collagen molecule is mainly formed by a sequence of Gly-X-Y where X and Y residues are usually proline and hydroxyproline. It is still unknown which specific amino acids are involved in collagen interaction with catechins, and if there is any covalent bond formation between the PACs and collagen. Stronger interaction between galloylated catechins and a peptide (composed mainly of proline) was observed when compared to non-galloylated compounds [17], supporting the greater interaction between EGCG, ECG, GCG and CG observed in the present study. Catechins might interact with the pyrrolidine ring present in proline, contributing to form hydrophobic bonds to collagen. Although the galloyl moiety seems to be a key component on the catechins structure, gallic acid by itself does not have the same effect, showing weaker collagen binding potential and less protective effect against collagen degradation [14]. Hoy’s solubility parameters of catechins (data not shown) and dentin activity show a weak correlation, underlining the complexity of the chemical structure of the monomers.

The biodegradation rates and inhibition of proteases by catechins also depend on the presence of galloyl moieties as demonstrated by our results. The strong correlation observed between fold increase and biodegradation rates indicates a dependence of increased collagen resistance of digestion and high cross-linking formation. Catechins are well known for their ability to inhibit MMPs [18,19]. Moreover, it was demonstrated that bacterial collagenase can be inhibited by catechins, especially EGCG, and the mechanism of inhibition might be related to changes in conformation of collagenase induced by hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with the enzyme [20]. The inhibitory effects of catechins on MMP and CTs were assessed using human recombinant forms which may behave differently from proteases bound to collagen.

Collagen degradation has been shown to be an important mechanism of decreasing the longevity of resin-dentin bonding [21]. Both inhibition of collagen-degrading enzymes and enhancement of collagen biomechanical properties have been demonstrated as effective alternatives to improve durability of adhesive restorations [12,22,23]. MMPs and CTs are proteolytic enzymes able to degrade collagen, and some members of these different families such as MMP-2, −3, −8 and −9, CT-B and CT-K are localized in dentin [24-29]. These enzymes are also involved in organic matrix degradation in caries progression [30,31]. The mechanisms of the inhibition of MMPs and CTs by catechins are still not completely understood. It was suggested that the inhibition might be either caused by EGCG binding to the catalytic site or to an allosteric site, by changing the enzyme conformation [19], or by a zinc-chelating effect [32]. EGCG has also been associated with the prevention of cardiovascular diseases by preserving lysosomal membranes and preventing the release of CTs [33].

EC inhibited MMP-9 activity at 0.65% (Figure 3A), but did not significantly affect digestion by bacterial collagenase. At the same concentration, EGC demonstrated low biodegradation rates and inhibition of MMP-9, but was not able to increase dentin mechanical properties. The present results support the hypothesis that a protective effect against collagen degradation by catechins might be related to different mechanisms, both the inhibition of proteolytic enzymes and changes in collagen structure. Moreover, a synergy between such mechanisms can be expected, with overlapping effects since cross-link formation stabilizes the collagen molecule and may also blocks enzymes cleavage sites [34]. For catechins in particular, these sites might be blocked by the gallate moieties present in CG, GCG, ECG and EGCG.

Conclusion

The presence of a galloyl moiety substantially enhances the dentin biomodification potential of the monomeric catechins. Galloylated catechins can inhibit both MMPs and CTs activity, and their inhibitory effect is concentration-dependent. EGCG might have superior clinical application due to its positive effects on both mechanical properties and stabilization of collagen against proteolytic degradation, showing inhibition of MMP even at 10- and 100-fold lower concentrations. Moreover, EGCG is a sufficiently abundant natural product and a sustainable resource.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH/NIDCR research grant (R01 DE21040).

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5. References

- 1.Castellan CS, Bedran-Russo AK, Karol S, Pereira PNR. Long-term stability of dentin matrix following treatment with various natural collagen cross-linkers. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dos Santos PH, Karol S, Bedran-Russo AKB. Nanomechanical properties of biochemically modified dentin bonded interfaces. J Oral Rehab. 2011;38:541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguiar TR, Vidal C, Phansalkar RS, Todorova I, Napolitano JG, McAlpine JB, Chen SN, et al. Dentin biomodification potential depends on polyphenol source. J Dent Res. 2014 Feb 26; doi: 10.1177/0022034514523783. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monagas M, Gomez-Cordovés C, Bartolomé B, Laureano O, Da Silva JMR. Monomeric, oligomeric, and polymeric flavan-3-ol composition of wines and grapes from Vitis vinifera L. cv. Graciano, Tempranillo, and Cabernet Sauvignon. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:6475–6481. doi: 10.1021/jf030325+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narotzki B, Reznick AZ, Aizenbud D, Levy Y. Green tea: a promising natural product in oral health. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao J, Chen T, Cao H, Chen L, Yang F. Molecular property–affinity relationship of flavanoids and flavonoids for HSA in vitro. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:310–317. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braicu C, Pilecki V, Balacescu O, Irimie A, Neagoe IB. The relationships between biological activities and structure of flavan-3-ols. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:9342–9353. doi: 10.3390/ijms12129342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du GJ, Zhang Z, Wen XD, Yu C, Calway T, Yun CS, Wang CZ. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is the most effective cancer chemopreventive polyphenol in green tea. Nutrients. 2012;4:1679–1691. doi: 10.3390/nu4111679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goo HC, Hwang YS, Choi YR, Cho HN, Suh H. Development of collagenase-resistant collagen and its interaction with adult human dermal fibroblasts. Biomater. 2003;24:5099–5113. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang HR, Covington AD, Hancock RA. Structure-activity relationships in the hydrophobic interactions of polyphenols with cellulose and collagen. Biopolymers. 2003;70:403–413. doi: 10.1002/bip.10499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napolitano JG, Gödecke T, Lankin DC, Jaki BU, McAlpine JB, Chen SN, Pauli GF. Orthogonal analytical methods for botanical standardization: determination of green tea catechins by qNMR and LC-MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.06.017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellan CS, Pereira PN, Grande RHM, Bedran-Russo AK. Mechanical characterization of proanthocyanidin–dentin matrix interaction. Dent Mater. 2010;26:968–973. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedran-Russo AK, Pashley DH, Agee K, Drummond JL, Miescke KJ. Changes in stiffness of demineralized dentin following application of collagen crosslinkers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;86:330–334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson JK, Zhao J, Wong W, Burt HM. The inhibition of collagenase induced degradation of collagen by the galloyl-containing polyphenols tannic acid, epigallocatechin gallate and epicatechin gallate. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21:1435–1443. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He L, Mu C, Shi J, Zhang Q, Shi B, Lin W. Modification of collagen with a natural cross-linker, procyanidin. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;48:354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bann JG, Peyton DH, Bächinger HP. Sweet is stable: glycosylation stabilizes collagen. FEBS Letters. 2000;473:327–340. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarni-Machado P, Cheynier V. Study of non-covalent complexation between catechin derivatives and peptides by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2002;37:609–616. doi: 10.1002/jms.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demeule M, Brossard M, Pagé M, Gingras D, Béliveau R. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition by green tea catechins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1478:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng XW, Kuzuya M, Kanda S, Maeda K, Sasaki T, Wang QL, Tamaya-Mori N, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate binding to MMP-2 inhibits gelatinolytic activity without influencing the attachment to extracellular matrix proteins but enhances MMP-2 binding to TIMP-2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013;415:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madhan B, Krishnamoorthy G, Rao JR, Nair BU. Role of green tea polyphenols in the inhibition of collagenolytic activity by collagenase. Int J Biol Macromol. 2007;41:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Ruggeri A, Cadenaro M, Di Lenarda R, De Stefano Dorigo E. Dental adhesion review: aging and stability of the bonded interface. Dent Mater. 2008;24:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrilho MRO, Geraldeli S, Tay F, De Goes MF, Carvalho RM, Tjäderhane L, Reis AF, et al. In vivo preservation of the hybrid layer by chlorhexidine. J Dent Res. 2007;86:529–533. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castellan CS, Bedran-Russo AK, Antunes A, Pereira PNR. Effect of dentin bimodification using naturally derived collagen cross-linkers: one-year bond strength study. Int J Dent. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/918010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/918010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin-De Las Heras S, Valenzuela A, Overall CM. The matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase A in human dentin. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:757–765. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sulkala M, Tervahartiala T, Sorsa T, Larmas M, Salo T, Tjäderhane L. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) is the major collagenase in human dentin. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzoni A, Mannello F, Tay FR, Tonti GA, Papa S, Mazzotti G, Di Lenarda R, et al. Zymographic analysis and characterization of MMP-2 and -9 forms in human sound dentin. J Dent Res. 2007;86:436–440. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzoni A, Papa V, Nato F, Carrilho M, Tjäderhane L, Ruggeri A, Jr, Gobbi P, et al. Immunohistochemical and biochemical assay for MMP-3 in human dentine. J Dent. 2011;39:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tersariol IL, Geraldeli S, Minciotti CL, Nascimento FD, Pääkkönen V, Martins MT, Carrilho M, et al. Cysteine cathepsins in human dentin-pulp complex. J Endod. 2010;36:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vidal CMP, Tjäderhane L, Scaffa PM, Tersariol IL, Pashley D, Nader HB, Nascimento FD, et al. Abundance of MMPs and cysteine cathepsins in caries-affected dentin. J Dent Res. 2014;93:269–274. doi: 10.1177/0022034513516979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tjäderhane L, Larjaval H, Sorsa T, Uitto V, Lannas M, Salo T. The activation and function of host matrix metalloproteinases in dentin matrix breakdown in caries lesions. J Dent Res. 1998;77:1622–1629. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770081001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nascimento FD, Minciotti CL, Geraldeli S, Carrilho MR, Pashley DH, Tay FR, Nader HB, et al. Cysteine cathepsins in human carious dentin. J Dent Res. 2012;90:506–511. doi: 10.1177/0022034510391906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quesada IM, Bustos M, Blay M, Pujadas G, Ardèvol A, Salvadó MJ, Bladé C, et al. Dietary catechins and procyanidins modulate zinc homeostasis in human HepG2 cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devika PT, Prince PSM. Preventive effect of (−)epigallocatechin-gallate (EGCG) on lysosomal enzymes in heart and subcellular fractions in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarcted Wistar rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;172:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brás NF, Gonçalves R, Mateus N, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ, de Freitas V. Inhibition of pancreatic elastase by polyphenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:10668–10676. doi: 10.1021/jf1017934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]