Abstract

Current dental resin undergoes phase separation into hydrophobic-rich and hydrophilic-rich phases during infiltration of the over-wet demineralized collagen matrix. Such phase separation undermines the integrity and durability of the bond at the composite/tooth interface. This study marks the first time that the polymerization kinetics of model hydrophilic-rich phase of dental adhesive has been determined. Samples were prepared by adding varying water content to neat resins made from 95 and 99wt% hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA) and 5 and 1wt% (2,2-bis[4-(2-hydroxy-3-methacryloxypropoxy)phenyl1]-propane (BisGMA) prior to light curing. Viscosity of the formulations decreased with increased water content. The photo-polymerization kinetics study was carried out by time-resolved FTIR spectrum collector. All of the samples exhibited two-stage polymerization behavior which has not been reported previously for dental resin formulation. The lowest secondary rate maxima were observed for water content of 10-30%wt. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) showed two glass transition temperatures for the hydrophilic-rich phase of dental adhesive. The DSC results indicate that the heterogeneity within the final polymer structure decreased with increased water content. The results suggest a reaction mechanism involving both polymerization-induced phase separation (PIPs) and solvent-induced phase separation (SIPs) for the model hydrophilic-rich phase of dental resin.

Keywords: Phase separation, polymerization, hydrophilic-rich phase, dental adhesive

1. INTRODUCTION

The median clinical lifetime of composite dental restoration is 3 to 8 years compared to 5 to 15 years for mercury amalgam [1]. The primary factor in the premature failure of composite restorations is recurrent decay [2] and 80-90% of recurrent decay is located at the gingival margin [3]. At this margin, the adhesive and its seal to dentin provides the primary barrier between the tooth and environment [4]. The failure of the adhesive allows Streptococcus mutans and other cariogenic bacteria to penetrate the composite/tooth interface; the bacteria colonize the subsurface tissues of the tooth initiating recurrent decay. Based on clinical investigations, the most significant factor in the long-term success of the composite restoration is the integrity of the adhesive bond layer [5-7]

The factors limiting the durability of the adhesive bond layer include incomplete polymerization, partial infiltration of the demineralized dentin matrix, phase separation, and hydrolytic / enzymatic degradation of the adhesive as well as the underlying demineralized collagen [8-11]. Sub-optimal polymerization leads to loosely cross-linked domains that can be readily penetrated by water. Incomplete infiltration [12] leads to water retention within the collagen/adhesive interfacial zone. As the adhesive diffuses through the wet, demineralized dentin matrix, it undergoes phase separation into hydrophobic and hydrophilic-rich phases. [11, 13]. Water will diffuse into the loosely cross-linked or hydrophilic domains. Water promoted degradation of the bonds within the adhesive [14-17] may undermine the dentin/adhesive bond integrity. The exposed demineralized collagen underneath the hybrid layer, arising due to incomplete impregnation of the dentin by the resin also undergoes hydrolytic degradation [12, 18]. Investigation by Pashley et al. [19] has also suggested possible degradation of exposed collagen by host derived matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Degradation of the exposed demineralized dentin underneath the hybrid layer could also promote access of saliva and oral bacteria compromising the dentin/adhesive bond integrity.

Previous investigation has shown the presence of limited cross-linkable di-methacrylate monomers (BisGMA) and hydrophobic initiator in the hydrophilic-rich phase of the dentin adhesive under wet conditions [20]. If the hydrophilic –rich phase that arises due to the phase separation fails to undergo substantial polymerization, the functional groups in the system become trapped as residual monomers and unreacted pendant radicals. The leaching of these unreacted monomers into the surrounding tissues has been associated with cytotoxicity. For example the unreacted monomethacrylate component of the adhesive, hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA), can cause apoptosis, interfere with the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the expression of type I collagen by gingival fibroblasts [21-24].

Ye and colleagues developed a ternary phase diagram of model dentin adhesive composed of 2,2-bis[4-(2-hydroxy-3-methacryloxypropoxy)phenyl1]-propane (BisGMA), hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA) and water [25]. The ternary phase diagram provides valuable quantitative information regarding the miscibility of the three components, distribution ratio and phase partitioning. As noted in the phase diagram, the model hydrophilic-rich phase contains very little cross-linker and consists mostly of the mono-methacrylate component HEMA.

The objective of this study was to understand the photo-polymerization kinetics of model hydrophilic-rich phases of dental adhesive as a function of water content. In vitro continuous monitoring of the polymerization kinetics of model hydrophilic-rich phase in methacrylate-based dentin adhesive was investigated for the first time. We hypothesize that the lowest rate of polymerization will occur at a critical concentration of water.

2. MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1 Model Adhesive Compositions and Sample Preparation

The model adhesive consists of mono-methacrylate component, 2-Hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA) (Acros Organics), di-methacrylate component, 2,2-bis[4-(2-hydroxy-3-methacryloxypropoxy) phenyl1]-propane (BisGMA) (Polysciences, Washington PA, USA), camphorquinone (CQ) as a hydrophobic photosensitizer and ethyl 4-(dimethylamino)benzoate (EDMAB) as a hydrophobic reducing agent (both from Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA) [26]. Model hydrophilic-rich phases were prepared from neat resins consisting of HEMA/BisGMA containing 95 and 99wt% of HEMA (HB95NR and HB99NR respectively). To avoid spectral interference from water, deuterium oxide (D2O, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc., Andover MA, USA) was added to the neat resins. The final composition of the D2O was based on total final weight of the mixture. The concentration of CQ and EDMAB was kept constant to 0.5wt% each based on the total final weight. D2O content was varied from 0wt% to maximum single phase composition (phase boundary). The composition of the samples is given in table 1. Three samples for each formulation were prepared. The neat resin samples were prepared by adding 0.5wt% CQ and EDMAB each into desired wt% of HEMA. The mixture was agitated until CQ and EDMAB dissolved completely. Then the required wt% BisGMA was added and it was agitated overnight to form a homogeneous mixture of neat resin. Samples with D2O content less than maximum single phase composition were prepared by adding desired wt% of D2O to the neat resin. The formulations are shown in a ternary phase diagram (Fig.1a). Then 0.5wt% of CQ and EDMAB each were added to the mixture based on the weight of D2O. The final concentration of the photo-initiators, CQ and EDMAB was 0.5wt% each based on total weight of the mixture.

Table 1.

Composition of each component in formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% and 99wt% HEMA

| wt% HEMA | wt% BisGMA | wt% D2O |

|---|---|---|

| Formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA | ||

| 94.95 ± 0.02 | 5.05 ± 0.02 | N/A |

| 84.95 ± 0.47 | 4.51 ± 0.04 | 10.54 ± 0.50 |

| 75.35 ± 0.60 | 4.00 ± 0.06 | 20.65 ± 0.65 |

| 65.92 ± 0.50 | 3.51 ± 0.07 | 30.57 ± 0.56 |

| 46.91 ± 0.22 | 2.50 ± 0.02 | 50.60 ± 0.23 |

| 39.95 ± 0.50 | 2.09 ± 0.03 | 57.97 ± 0.52 |

| Formulations made from neat resin containing 99wt% HEMA | ||

| 98.99 ± 0.01 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | N/A |

| 78.55 ± 0.86 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 20.64 ± 0.86 |

| 69.06 ± 0.13 | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 30.23 ± 0.13 |

| 49.00 ± 0.25 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 50.49 ± 0.26 |

| 29.2 ± 1.4 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 70.5 ± 1.4 |

*Photo-initiators CQ and EDMAB are both 0.5(wt)% in the samples above

Figure 1.

(a) Ternary phase diagram for water, BisGMA and HEMA. The dashed line exhibits the phase boundary line. The filled triangles and circles represent formulations made from Neat resins- HB95NR and HB99NR respectively. (b) Viscosity of liquid formulations shown by filled triangles and circles in the ternary phase diagram.

The miscibility limit for samples at maximum single phase composition was determined by cloud point detection [11]. For these samples D2O was added drop-wise to the neat resin until the mixture turned cloudy, then the neat resin was added drop-wise until the cloudy mixture turned clear. This was done carefully such that a single drop changed the appearance of the mixture. CQ and EDMAB were added to the mixture based on the weight of D2O so that the concentration of each will remain constant to 0.5wt% of the total weight of the mixture. Since the photo-initiators were hydrophobic, their addition to the mixture turned the solution cloudy again which was then back titrated with the neat resin until the mixture was clear. The final mixture was single phase solution containing maximum D2O (e.g. at miscibility limit) as indicated by the triangular and circular points on the phase boundary line in Fig. 1a.

2.2 Photo-Polymerization kinetics study

Polymerization kinetics was monitored in situ for approximately 2 hours using Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 400 Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR) with a resolution of 4 cm-1 in the ATR sampling mode. This technique was used previously to monitor the photo-polymerization kinetics [26-28]. The model hydrophilic-rich phases with varying D2O content were cured for 40s using dental curing light, Spectrum® 800, Dentsply, Milford, DE, USA at 550 mW/cm2. A fixed volume of 30μl of the sample was placed on the ATR crystal. A transparent coverslip was placed on the sample and the edges of the coverslip were sealed with tape to prevent evaporation of D2O. The decrease in band intensity ratio for intensity at 1637 cm-1 to that at 1716 cm-1 (carbonyl) was monitored continuously during the polymerization. The polymerization kinetics of three samples for each formulation was studied. The degree of conversion (DC) was determined using the following equation which was based on band intensity ratio before and after curing:

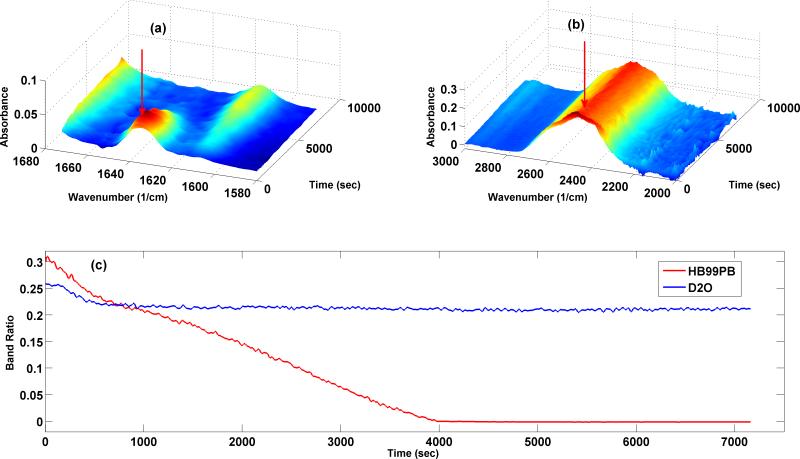

In order to reduce variables that may impact the polymerization kinetics study, the evaporation of D2O was prevented by sealing the sides of the cover slip with tape and the thickness of the sample on the ATR crystal was maintained constant by drawing 30 μl of the formulation for each measurement. For the kinetic study the light intensity was kept constant at 550 mW/cm2. Fig. 2 shows a representative profile for D2O and band ratio of C=C bond intensity to that of C=O bond. It can be seen that the D2O profile remained almost constant throughout whereas the band ratio decreased as the polymerization reaction continued. The slight decrease in D2O profile at the beginning may be due to the slight difference in diffusion (D2O is a small molecule compared with HEMA and BisGMA) from the center of the ATR crystal during the light curing. The rate of polymerization was determined by taking the first derivative of the time versus conversion curve.

Figure 2.

3D-surface plots of absorbance of (a) carbon-carbon double bond in methacrylate group of monomers and (b) D-O single bond in D2O during in-situ polymerization. (c) Band ratio of representative HB99PB formulation and intensity profile of D2O during in-situ polymerization. The profile for the latter stayed almost constant during polymerization eliminating the possibility of change in viscosity due to evaporation of D2O.

2.3 Measurement of viscosity

Brookfield DV-II +Pro viscometer with a cone/plate set up was used to measure the viscosity of the formulations at varying shear rate. For each formulation viscosity of three samples was measured at 25.0 ± 0.2 °C. The sample volume was kept constant to 0.5ml.

2.4 Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) study

Homogeneous solution of each formulation was placed in a low mass DSC pan to the brim and then it was covered using glass coverslip. The sample was then cured for 40s using the same dental curing light at 550 mW/cm2. Three samples for each formulation were prepared. The samples were left overnight. The glass coverslips were removed and the samples were then placed in a vacuum chamber at 37°C to evaporate the D2O. The mass of the sample was measured at specific time intervals until a constant mass was reached. Modulated Temperature DSC (MTDSC) was carried out using TA instruments model DSC Q200. The method for MTDSC was comparable to the technique used previously to determine the thermal behavior of dental adhesive cured in the presence of ethanol [27]. The temperature was modulated sinosoidally with an amplitude of 2°C every 60s in presence of purged nitrogen gas at a flow rate of 40ml/min. Temperature was varied from -10°C to 200°C. Samples were heated and cooled at 3°C/min. Two heating/cooling cycles were carried out for each sample analysis. The data were analyzed using Universal Analysis software (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE).

Sample name, ‘HBxD2Oy’ means that the formulation has been made by adding y%wt of D2O into HEMA/BisGMA (HB) neat resin containing x%wt of HEMA. Sample names with ‘PB’ means these samples are at the phase boundary (PB).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Polymerization kinetic study of model hydrophilic-rich phase

In the case of formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA, the D2O content was varied from 0wt% to miscibility limit which was 57.96wt%. Table 1 shows the composition of all of the components in these formulations. Fig. 3 shows the representative results from the kinetic study for these formulations. All of the samples exhibited substaintial degree of conversion (Fig. 3a). The formulation with 10-30wt%t D2O content showed lower secondary rate maxima (Fig. 3b and c). A decreasing trend for the initial polymerization rate with the increase in D2O content (Fig. 3c) was observed for formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA. Formulations made from neat resin containing 99wt% HEMA exhibited a similar result. In this case, the lower secondary rate maxima was observed at D2O content of 20wt% (Fig. 4b). Fig. 4a shows that the formulations made from neat resin with 99wt% HEMA also exhibit substantial degree of conversion and the representative rate profile for these formulations are given in Fig. 4b. The D2O content in this case was also varied from 0wt% to miscibility limit which was 70.54wt%. Table 1 exibits the composition of the formulations made from neat resin containing 99wt% HEMA and table 2 summarizes the average degree of conversion and rate of polymerization. In case of formulations beyond 20wt% D2O content made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA, the secondary rate maxima increased with the addition of D2O content.

Figure 3.

(a) Degree of conversion and (b) rate of polymerization of formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA for varying D2O content. The error bars are not in the figures, but the standard deviation for the final degree of conversion and rate maxima are given in Table 2. (c) Initial and secondary rate maxima as a function of D2O content for formulations made from 95wt% HEMA. Secondary rate maxima decreases until D2O content of 20wt%, then it increases with D2O content and the initial rate maxima decreases with increase in D2O content.

Figure 4.

(a) Degree of conversion and (b) rate of polymerization of formulations made from neat resin containing 99wt% HEMA for varying D2O content. The error bars are not in the figures, but the standard deviation for the final degree of conversion and rate maxima are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Average degree of conversion and rate of polymerization for each formulation

| Formulation name | Degree of conversion in 2hrs (%) | Initial rate of polymerization (s−1) × 103 | Secondary rate maxima (s−1) × 104 | Appearance after polymerization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA | ||||

| HB95NR | 66.0 ± 0.9 | 47.0 ± 2.1 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | Clear |

| HB95D2O10 | 78.6 ± 6.9 | 47.0 ± 6.0 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | Almost clear |

| HB95D2O20 | 87.3 ± 2.5 | 37.8 ± 5.6 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | Almost clear |

| HB95D2O30 | 78 ± 12 | 30.5 ± 3.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | Translucent |

| HB95D2O50 | 99.5 ± 0.8 | 20.1 ± 4.5 | 3.0 ± 0.7 | Turbid white |

| HB95PB | complete | 16.6 ± 4.7 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | Turbid white |

| Formulations made from neat resin containing 99wt% HEMA | ||||

| HB99NR | 67.5 ± 2.2 | 46.1 ± 2.9 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | Clear |

| HB99D2O20 | 63.3 ± 9.9 | 34.9 ± 2.6 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | Almost clear |

| HB99D2O30 | 95.1 ± 2.3 | 35.9 ± 4.8 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | Translucent |

| HB99D2O50 | 88 ± 11 | 20.0 ± 6.3 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | Turbid white |

| HB99PB | complete | 19.4 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | Turbid white |

3.2 Viscosity study

It was observed that as D2O content increased, the viscosity of the formulations decreased as shown in Fig. 1b. Formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA possessed higher viscosity compared to formulations from neat resin containing 99wt% HEMA with similar D2O content. The viscosity for formulations prepared from 95wt% HEMA varied from 3.8 cP to 8.2 cP. In the case of formulations made from 99wt% HEMA, it varied from 2.8 cP to 6.6 cP.

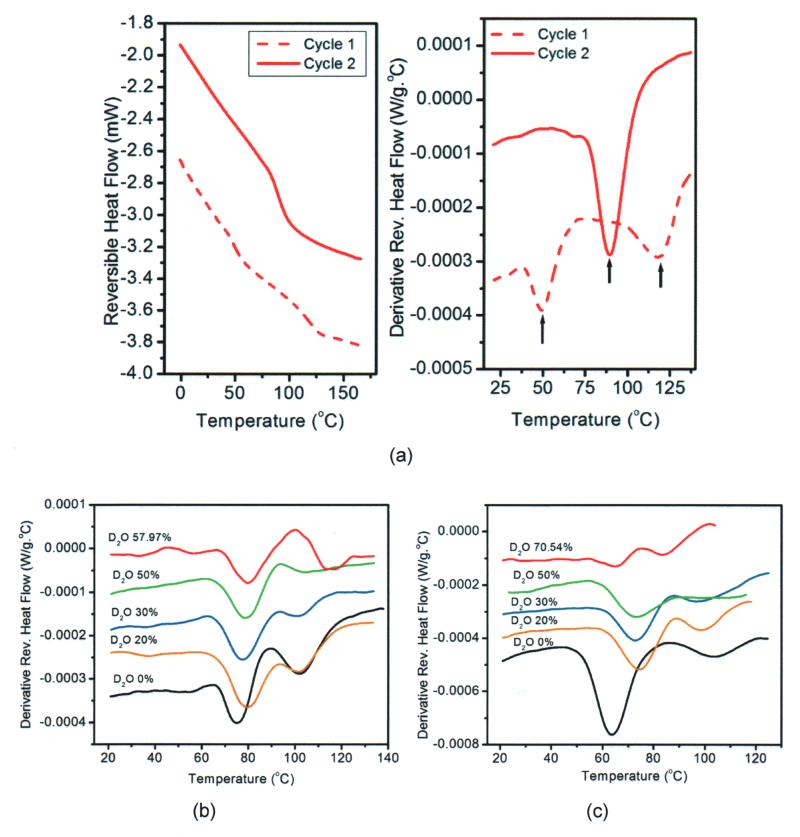

3.3 Determination of glass transition temperature

Representative result for moduluated DSC (MTDSC) with first and second heating cycles for the sample HB95NR is shown in Fig. 5a. The glass transition temperatures were determined from the derivative of the reversible heat flow signal. Fig. 5b and c shows representative DSC results for all the formulations made from 95 and 99wt% HEMA respectively. Table 3 summarizes the average glass transition temperatures for the formulations. It was observed that the heterogeneity within the samples decreased with increasing D2O content until near the micibility limit for formulations made from both types of neat resins. For neat resin with 95 and 99wt% HEMA, two glass transition temperatures were observed for the initial heating cycle. With increase of D2O content the difference between the two glass transition temperatures reduced until they merged and became one at 50wt% D2O content for formulations made from 95 and 99wt% HEMA, respectively. At miscibility limit the samples showed increasing heterogeneity and they exhibited two glass transition temperatures. For all the formulations structural rearrangement occurred during the second heating cycle reducing the heterogeneity within the samples and causing them to exhibit one glass transition temperature in between the two glass transition temperatures or higher than the single or second glass transition temperature for the first heating cycle. Table 3 shows the glass transition temperatures obtained from both the cycles.

Figure 5.

(a) Reversible heat flow signals for cycle 1 and 2 of polymer sample made from formulation HB95NR and the derivative of reversible heat flow signals showing the glass transition temperature for the two cycles. Differential scanning calorimetric study of polymer samples for formulations with varying D2O content made from neat resins containing (b) 95wt% HEMA and (c) 99wt% HEMA. Presence of the two glass transition peak indicates heterogeneity within the samples.

Table 3.

Glass transition temperature (Tg) of polymer samples made from formulations studied

| Formulation name | First Tg, (°C) during initial heating cycle | Second Tg, (°C) during initial heating cycle | Tg, (°C) during second heating cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formulations made from neat resin containing 95wt% HEMA | |||

| HB95NR | 76.0 ± 0.5 | 106.0 ± 3.4 | 102.7 ± 3.5 |

| HB95D2O20 | 76.9 ± 3.6 | 103.4 ± 7.1 | 106.6 ± 1.6 |

| HB95D2O30 | 79.2 ± 3.1 | 101.2 ± 1.4 | 105.0 ± 3.3 |

| HB95D2O50 | 80.3 ± 1.9 | N/A | 104.0 ± 2.7 |

| HB95PB | 78.5 ± 0.5 | 108.8 ± 6.8 | 105.1 ± 2.2 |

| Formulations made from neat resin containing 99wt% HEMA | |||

| HB99NR | 63.2 ± 3.1 | 101.8 ± 0.6 | 93.4 ± 1.6 |

| HB99D2O20 | 72.0 ± 1.5 | 98.1 ± 0.7 | 98.7 ± 1.9 |

| HB99D2O30 | 76.3 ± 2.7 | 99.2 ± 1.8 | 99.5 ± 1.1 |

| HB99D2O50 | 79.7 ± 3.6 | N/A | 101.1 ± 2.8 |

| HB99PB | 71 ± 8 | 87.3 ± 7.7 | 101.0 ± 1.9 |

4. DISCUSSIONS

In the wet bonding technique, the demineralized collagen matrix stays excessively wet. As a result during infiltration, the current dental adhesive undergoes physical separation into hydrophobic and hydrophilic-rich phases [11]. Previous study has shown that the hydrophobic components of the dental adhesive (BisGMA, CQ and EDMAB) are present in minimal amount in the hydrophilic-rich phase [20]. This study focused on the in situ kinetics of polymerization reaction of model hydrophilic-rich phases and their resultant structures.

The model hydrophilic-rich phases were prepared by adding D2O to neat resins containing 95 and 99wt% HEMA. To simplify the compositions and to gain an initial understanding of polymerization behavior, this work only focused on the model dentin adhesives. Commercial adhesives contain solvents but we used neat resin without volatile solvent because it is possible that under clinical condition the majority of the solvent may evaporate leaving behind mostly water. BisGMA is the cross-linkable component that imparts desirable mechanical properties to the adhesive upon polymerization. Since this is present in very low quantity in the model hydrophilic-rich phases, the resultant polymer may be more susceptible to degradation because it will consist of mostly linear polymer chains.

Physical phase separation of dental resin in presence of water was reported earlier [11, 29] but there had been very few investigations regarding phase separation during polymerization for dental resin [30]. The time scale (up to 2 hours) of in-situ observation of the photo-polymerization kinetics has not been reported before. It is important to understand the polymerization mechanism of model hydrophilic-rich phase of dental resin since this domain may influence the durability of the dentin/adhesive bond.

Our results indicate that the model hydrophilic-rich phase undergoes both polymerization- and solvent-induced phase separation during curing. Polymerization induced phase separation (PIPs) occurs within a homogenous solution of non-reactive component in reactive monomers during polymerization [31, 32]. Initially during polymerization of the model hydrophilic-rich phase without D2O, the polymer is soluble in the monomer mixture. As polymerization continues the polymer domain separates from the monomer mixture. PIPs has application in producing multiphase composite materials [33] and it is used in the preparation of polymer liquid crystal (PDLC) [34]. The latter is used in optical switches, variable transmittance windows and reflective displays [35]. In the presence of a solvent, the polymer that forms during curing undergoes phase separation into solvent-rich and polymer-rich phases known as solvent induced phase separation (SIPs) [36, 37].

A secondary rate maximum was observed for all the formulations studied here. Bimodal rate was observed previously for the polymerization of methacrylate system [38-41]. According to Horie and colleagues [40], the reactivity of pendant double bonds in a propagating polymer radical was lower than that of free monomers causing their concentration to increase during the polymerization. These pendant groups led to localized regions of higher cross-linking density which formed micro-gels and triggered a secondary gel effect within the micro-gel [40]. Yu and co-authors [41] suggested that some pendant double bonds became trapped within the micro-gel, limiting their availability for reaction and that these species would become reactive in propagation at some point during the reaction leading to secondary maxima or triggering a second Trommsdorff effect. Li and colleagues [42] observed formation of macro-gel at the beginning of secondary rate maxima for a dilute methacrylate system (HEMA/diethylene glycol dimethacrylate(DEGDMA)) under low light intensities and near the end of first rate maxima under higher light intensities.

The results from the current investigation suggest that the secondary rate maxima may also be associated with PIPs and SIPs. Based on the results of the thermal analysis and polymerization kinetics investigations, a polymerization mechanism involving PIPs and both PIPs/SIPs (Fig. 6) is proposed for the dilute dental resins studied here. Fig. 6a illustrates the possible polymerization mechanism involving only PIPs for the neat resin samples. It is likely that for the neat resins (HB95NR and HB99NR), after auto-acceleration, localized regions of higher degree of conversion and/or cross-linking density are formed. These isolated regions form micro-gels or polymer particles. As polymerization continues within the micro-gel, it grows in size and may precipitate out due to polymerization induced phase separation (PIPs) as shown by schematic B in Fig. 6a, entrapping reactive species (unreacted monomer, free radicals, etc.). Since the viscosities of the neat resins are far lower than the hydrophobic-rich phase [43], reactive species are still able to diffuse into the micro-gel. At some point the growth of the micro-gels may become diffusion controlled and they become swollen with diffused reactive species. It is likely that diffusion will increase the overall available reactive species within the micro-gel and cause a second Trommsdorff effect giving rise to the secondary rate maxima. The micro-gel and its surroundings will continue to polymerize to form higher and lower cross-linked regions within the polymer and at a later stage, the micro-gel may start to form a network with the surrounding matrix (schematic C in Fig. 6a) giving rise to the final polymer structure (schematic D in Fig 6a).

Figure 6.

Schematic showing possible polymerization reaction involving (a) polymerization-induced phase separation (PIPs), (b) solvent-induced phase separation (SIPs) and PIPs both. The mechanism in (a) is representative for neat resin and that in (b) is for formulations containing more than 30wt% water content. The resultant structure will be heterogeneous with higher and lower cross-linking density as indicated by the presence of two glass transition temperatures. The final structure in (b) will have water droplets dispersed throughout which may lead to gradual plasticization and hydrolysis of the ester linkages within the polymer.

A separate mechanism involving both PIPs and SIPs for dilute dental resin containing D2O as solvent is proposed (Fig. 6b). Prior to polymerization, the samples were homogeneous single phase solutions of monomer and solvent (D2O) as shown by schematic E in Fig. 6b. Immediately after auto-acceleration, isolated regions of increased monomer/polymer conversion and/or higher cross-linking density form which represent the micro-gels. As polymerization continues within the micro-gels, they grow in size. At some point the miscibility limit of the polymer in monomer and the solvent may cross the polymer phase boundary line. It is likely that the micro-gel then precipitates out due to PIPs and SIPs (schematic F in Fig. 6b). The formulations studied here have low viscosity, allowing the reactive species to diffuse into the micro-gels easily and resulting in the secondary rate shown by the region FH of the polymerization kinetic graph in Fig. 6b. During the later stage of polymerization (region GH of polymerization kinetic graph in Fig. 6b), the micro-gels may form a network with the surrounding loosely cross-linked matrix. During this time the miscibility of the polymer matrix in D2O may exceed the limit causing D2O to separate as droplets as shown in schematic G in Fig. 6b. The final structure could be composed of higher and lower cross-linked regions with solvent droplets dispersed within the matrix (schematic H in Fig. 6b). The two glass transition temperatures shown as an inset within the polymerization kinetic graph in Fig. 6a and b could be attributed to the higher and lower cross-linked regions.

The solubility of polymer is expected to be higher within monomer solution compared to solvent such as D2O. Therefore it is possible that the size of the micro-gels that precipitate out in the neat resin is smaller than those in the solvent. This may result in shorter diffusion path for the reactive species to diffuse into the micro-gels allowing the secondary rate maxima to appear earlier for neat resins. With the addition of D2O in the neat resin, the size of the micro-gels that precipitate out increases, reducing the rate of diffusion of the reactive species into the micro-gels. This may cause the secondary rate maxima to be delayed with the increase in D2O content. The monomer concentration decreases with increasing D2O content which may also contribute to a delay in the secondary rate maxima. In the case of formulations at the miscibility limit, the D2O content is so high that immediate precipitation may occur following exposure to the curing light. Under these circumstances, the secondary rate maxima will appear earlier than the formulation with 50wt% D2O despite the slow diffusion of the reactive species and reduced monomer concentration.

For all the formulations containing D2O, it is likely that the micro-gel will precipitate out due to both PIPs and SIPs. As D2O is added to the dilute neat resins, the viscosity and monomer concentration will decrease. This will cause the distance between reactive species and monomers to increase [42]. Therefore despite the increased mobility of the reactive species due to reduced viscosity, the secondary rate maxima decreased until D2O content of 20wt%. In the case of formulations containing less than 20wt% D2O, the micro-gel could be initially soluble in the D2O. This could reduce the availability of entrapped reactive species within the micro-gel by allowing them to readily diffuse out of the micro-gel. This may subsequently decrease the second Trommsdroffs effect. It is possible that for formulations containing less than 20wt% D2O, precipitation of the micro-gel is due mainly to PIPs.

Beyond 30wt% D2O content, the micro-gel may precipitate out rapidly since SIPs becomes dominant with increasing D2O content. Addition of D2O beyond 30wt% facilitates precipitation of more micro-gels which would cause reactive species to be trapped in close proximity. Moreover with the addition of D2O, the mobility of monomers and reactive species is enhanced due to a decrease in viscosity. This would allow more monomers and reactive species to diffuse into the micro-gels causing the availability of these species within the micro-gels to be more than those in formulations containing less than 30wt% D2O. It is likely that the increasing trend of the secondary rate maxima for D2O content beyond 20wt% is due to enhanced micro-gel precipitation caused by SIPs and increased mobility of monomers/reactive species. This could also be attributed to the complete degree of conversion within 2 hours for formulations with very high D2O content such as 50%wt and miscibility limit.

The large standard deviation in the rate of polymerization could be attributed to high sensitivity of the sample to its surroundings during polymerization and presence of dissolved oxygen within the sample. These issues could make it difficult to control the polymerization process within the sample.The neat resins (HB95NR and HB99NR) always exhibited lower degree of conversion than the formulations with D2O. This could be due to precipitation of limited micro-gel and higher viscosity during curing imposing greater restriction on the motion of monomers/reactive species compared to formulations containing D2O. The higher viscosity of the formulations made from neat resin with 95wt% HEMA compared to those from neat resin with 99wt% HEMA could be attributed to the higher composition of BisGMA in the case of formulations from neat resin containing 95%wt HEMA.

The appearance of samples from neat resins and those from formulations with 10 and 20wt% D2O were transparent during polymerization. For these solutions micro-gel precipitation was likely due mainly to PIPs. The phase separation during polymerization was not visible. The appearance of samples during curing was translucent for formulation with 30wt% D2O and turbid for formulations containing above 30wt% D2O. For formulations with D2O content above 30wt%, SIPs might have played the dominant role in precipitation of micro-gel. Higher D2O content could have enhanced the size of the micro-gel that precipitated out leading to micron-scale phase separation during polymerization.

The polymer samples from neat resins exhibited two glass transition temperatures implying the presence of higher and lower cross-linked regions. The existence of the two glass transition temperatures in dental polymer was reported previously using the modulated DSC technique [27]. For the neat resins, PIPs resulted in polymer and monomer rich phases during curing. The polymer rich phase may represent micro-gel with higher cross-linking density and the monomer rich phase results in loosely cross-linked regions around the micro-gels. This composition could account for the two glass transition temperatures observed for the neat resins. As D2O content in the formulations is increased, the difference between the two glass transition temperatures decreases. This may indicate that the heterogeneity within the polymer samples reduces with increasing D2O content. The solutions become more dilute with the addition of D2O and during its polymerization SIPs may cause formation of two distinct regions, solvent and polymer-rich phases. In the case of formulations containing D2O, our results indicate that in the final structure the difference in cross-linking density within the polymer rich phase (micro-gel during early stage of polymerization) and solvent rich phase becomes subtle causing the two glass transition temperatures to approach each other or to merge to become one. In the case of samples cured in the presence of intermediate amount of water, such as HB95D2O50 and HB99D2O50, the two glass transition temperatures merged to form one, indicating reduced heterogeneity within the structure.

Lovell and colleagues attributed the heterogeneity within the dental polymer network to diffusion limitation, cyclizations and micro-gel formation [44]. Primary cyclization occurs when a pendant double bond reacts intramolecularly with a radical on the same propagating chain [44]. Primary cyclization enhances micro-gel formation but does not contribute to cross-linking density [44] and thus it is possible that with the increase in D2O content within the formulation, micro-gel formation is enhanced with more primary cyclization but cross-linking density within the micro-gel is not increased. This can reduce the differences in cross-linking density between micro-gels and the surrounding matrix causing the two glass transition temperatures to approach each other or merge.

At the miscibility limit solvent induced phase separation (SIPs) becomes dominant leading to increased formation of polymer rich phases, i.e. distinct regions of higher cross-linking. Hence at the miscibility limit, two glass transition temperatures were observed but the two glass transition temperatures were very close compared to the neat resin indicating that cyclization might have played the major role in the formation of the micro-gel. The glass transition temperature (Tg) of polyHEMA is about 100°C [45, 46]. Except for HB95NR the second Tg was approximately 100°C indicating that the higher cross-linked regions consisted mostly of polyHEMA with some cross-linking. The increased concentration of BisGMA in HB95NR led to increased crosslinking and higher second Tg. The first Tg represented the loosely cross-linked regions (matrix); the composition of the matrix is likely to be polyHEMA.

Both monomers and D2O could act as plasticizers lowering the Tg. Since the formulations containing D2O showed higher degree of conversion than the neat resins, there could be less residual monomer in the polymer sample causing the first Tg to be higher than that for neat resins. Formulations with high D2O content exhibited complete degree of conversion and thus plasticization within these samples could have been due to the presence of D2O only. After the first cycle of heating, rearrangements within the structures may have reduced the heterogeneity and hence for the second cycle of heating, only one glass transition temperature is observed for all formulations. The glass transition temperatures for the second cycle varied within a range very close to 105°C for HB95 series and 100°C for HB99 series, respectively, in the case of all formulations except for the neat resins. The glass transition temperature for second cycle was lower for the neat resins which could be due to their incomplete degree of conversion compared to formulations containing D2O.

D2O droplets in the final polymer structure that may arise from hydrophilic-rich phase (schematic G in Fig. 6b) may be retained or evaporated leaving pores within the structure. Previous investigation using Micro-X-ray tomography showed the presence of pores in control formulation (HEMA 45wt%/BisGMA 55wt%) of dental resin when cured in presence of water [47]. Under clinical conditions, the loosely cross-linked regions and pores/water droplets within the polymer network may promote oral fluid penetration into the polymer leading to plasticization and degradation. Fluid can also be forced to enter the polymer by pulpal pressure but the above mentioned factors may enhance the overall fluid flow into the polymer. The series of cascading events prompted by the diffusion of fluid may lead to failure of the bond at the composite/tooth interface and ultimately, failure of the composite restoration.

It is noted that this study was carried out at room temperature instead of body temperature and we used neat resin without volatile solvent. Although these impede a direct correlation to the clinical condition, the results provide clear evidence that water-induced /polymerization-induced phase separation in adhesive should be considered in the development of future materials. The results from this work support previous conclusions that water-compatible crosslinkable comonomers should be included in adhesive formulations to address the defects that form in adhesives exposed to the wet, oral environment [20, 25, 29, 43, 48, 49]. Inclusion of hydrophilic cross-linker in the dental adhesive will result in the presence of more cross-linker in the hydrophilic-rich phase following phase separation under clinical conditions. It is likely that this composition will have a positive impact on the crosslink density of the hydrophilic-rich phase. Higher crosslink density will reduce the vulnerability of the hydrophilic-rich phase to hydrolytic degradation.

This paper also alerts dentists to factors that may negatively impact the bond formed at the tooth/adhesive interface and factors that have previously received limited attention. Knowledge of the phenomenon described in this paper alerts the dentist to the importance of isolating those areas that are particularly susceptible to high concentrations of water, e.g. the gingival margin. In class II and V composite restorations, recurrent decay is most often localized at the gingival margin and is linked to failure of the bond between the tooth and composite and increased levels of the cariogenic bacterium, Streptococcus mutans, localized around the perimeter of these materials [9, 50, 51].

5. CONCLUSION

The polymerization kinetics of model hydrophilic-rich phases cured in the presence of varying concentrations of D2O was determined using Fourier Transform Infrared spectrophotometer. The polymerization kinetics of the model hydrophilic-rich phase was influenced by both polymerization-induced phase separation and solvent-induced phase separation. Lowest secondary rate maxima was observed for D2O content of 10-30wt% (critical D2O content). With further increase in D2O, solvent induced phase separation becomes increasingly dominant facilitating the precipitation of microgel or polymer particles during curing. This phenomenon may have contributed to the increase in secondary rate maxima above 20wt% D2O content. The polymer samples from the model hydrophilic-rich phases were hetereogenous with regions of higher and lower cross-link structure. Although all model hydrophilic-rich phase exhibited a substantial degree of conversion in the presence of sufficient photo-initiator, the resultant polymer will still be loosely cross-linked compared to the hydrophobic-rich phase due to the presence of a limited amount of cross-linker BisGMA. This study indicates possible water droplet retention or pore formation within the polymer from hydrophilic-rich phase. Although pulpal pressure may cause fluid permeation into the dental polymer, presence of loosely cross-linked regions, water droplets/pore within the polymer may facilitate the overall fluid flow into the dentin/adhesive interface enhancing plasticization, hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation of the dental polymer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This investigation was supported by Research Grant: R01DE14392 (PS) and R01 DE022054 (PS, JSL) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernardo M, Luis H, Martin MD, Leroux BG, Rue T, Leitão J, et al. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite posterior restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:775–83. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mjor IA, Dahl JE, Moorhead JE. Age of restorations at replacement in permanent teeth in general dental practice. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2000;58:97–101. doi: 10.1080/000163500429208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Carrera C, Chen R, Li J, Lenton P, Rudney JD, et al. Degradation in the dentin– composite interface subjected to multi-species biofilm challenges. Acta Biomaterialia. 2014;10:375–83. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roulet JF. Benefits and disadvantages of tooth-coloured alternatives to amalgam. Journal of Dentistry. 1997;25:459–73. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(96)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donmez N, Belli S, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Ultrastructural correlates of in vivo/in vitro bond degradation in self-etch adhesives. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:355–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kermanshahi S, Santerre JP, Cvitkovitch DG, Finer Y. Biodegradation of resin-dentin interfaces increases bacterial microleakage. J Dent Res. 2010;89:996–1001. doi: 10.1177/0022034510372885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer P, Ye Q, Park J, Topp EM, Misra A, Marangos O, et al. Adhesive/Dentin interface: the weak link in the composite restoration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:1989–2003. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliades G, Vougiouklakis G, Palaghias G. Heterogeneous distribution of single-bottle adhesive monomers in the resin–dentin interdiffusion zone. Dental Materials. 2001;17:277–83. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(00)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santerre J, Shajii L, Leung B. Relation of dental composite formulations to their degradation and the release of hydrolyzed polymeric-resin-derived products. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine. 2001;12:136–51. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santini A, Miletic V. Quantitative micro - Raman assessment of dentine demineralization, adhesive penetration, and degree of conversion of three dentine bonding systems. European journal of oral sciences. 2008;116:177–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer P, Wang Y. Adhesive phase separation at the dentin interface under wet bonding conditions. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2002;62:447–56. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto M, Nagano F, Endo K, Ohno H. A review: biodegradation of resin–dentin bonds. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2011;47:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toledano M, Yamauti M, Osorio E, Monticelli F, Osorio R. Characterization of micro-and nanophase separation of dentin bonding agents by stereoscopy and atomic force microscopy. Microscopy and Microanalysis. 2012;18:279. doi: 10.1017/S1431927611012621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrilho MRdO Tay FR, Pashley DH, Tjäderhane L. Marins Carvalho R. Mechanical stability of resin–dentin bond components. Dental Materials. 2005;21:232–41. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiaraputt S, Mai S, Huffman B, Kapur R, Agee K, Yiu C, et al. Changes in resin-infiltrated dentin stiffness after water storage. Journal of dental research. 2008;87:655–60. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feitosa VP, Leme AA, Sauro S, Correr-Sobrinho L, Watson TF, Sinhoreti MA, et al. Hydrolytic degradation of the resin-dentine interface induced by the simulated pulpal pressure, direct and indirect water aging. Journal of Dentistry. 2012;40(12):1134–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yiu C, King N, Pashley D, Suh B, Carvalho R, Carrilho M, et al. Effect of resin hydrophilicity and water storage on resin strength. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5789–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto M, Tay FR, Ohno H, Sano H, Kaga M, Yiu C, et al. SEM and TEM analysis of water degradation of human dentinal collagen. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2003;66B:287–98. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Yiu C, Hashimoto M, Breschi L, Carvalho RM, et al. Collagen Degradation by Host-derived Enzymes during Aging. Journal of Dental Research. 2004;83:216–21. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye Q, Park J, Parthasarathy R, Pamatmat F, Misra A, Laurence JS, et al. Quantitative analysis of aqueous phase composition of model dentin adhesives experiencing phase separation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2012;100:1086–92. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang H-H, Guo M-K, Kasten FH, Chang M-C, Huang G-F, Wang Y-L, et al. Stimulation of glutathione depletion, ROS production and cell cycle arrest of dental pulp cells and gingival epithelial cells by HEMA. Biomaterials. 2005;26:745–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falconi M, Teti G, Zago M, Pelotti S, Breschi L, Mazzotti G. Effects of HEMA on type I collagen protein in human gingival fibroblasts. Cell biology and toxicology. 2007;23:313–22. doi: 10.1007/s10565-006-0148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paranjpe A, Bordador L, Wang M-y, Hume W, Jewett A. Resin monomer 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) is a potent inducer of apoptotic cell death in human and mouse cells. Journal of dental research. 2005;84:172–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spagnuolo G D'Antò V, Cosentino C, Schmalz G, Schweikl H, Rengo S. Effect of N-acetyl-l-cysteine on ROS production and cell death caused by HEMA in human primary gingival fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1803–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye Q, Park J, Laurence J, Parthasarathy R, Misra A, Spencer P. Ternary phase diagram of model dentin adhesive exposed to over-wet environments. Journal of dental research. 2011;90:1434–8. doi: 10.1177/0022034511423398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye Q, Park J, Topp E, Wang Y, Misra A, Spencer P. In vitro performance of nano-heterogeneous dentin adhesive. Journal of dental research. 2008;87:829–33. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye Q, Spencer P, Wang Y, Misra A. Relationship of solvent to the photopolymerization process, properties, and structure in model dentin adhesives. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2007;80:342–50. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye Q, Wang Y, Williams K, Spencer P. Characterization of photopolymerization of dentin adhesives as a function of light source and irradiance. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2007;80:440–6. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer P, Wang Y, Walker M, Wieliczka D, Swafford J. Interfacial chemistry of the dentin/adhesive bond. Journal of Dental Research. 2000;79:1458–63. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790070501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye Q, Wang Y, Spencer P. Nanophase separation of polymers exposed to simulated bonding conditions. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2009;88B:339–48. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo K. The morphology and dynamics of polymerization-induced phase separation. European polymer journal. 2006;42:1499–505. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murata K, Anazawa T. Morphology and mechanical properties of polymer blends with photochemical reaction for photocurable/linear polymers. Polymer. 2002;43:6575–83. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keizer HM, Sijbesma RP, Jansen JF, Pasternack G, Meijer E. Polymerization-induced phase separation using hydrogen-bonded supramolecular polymers. Macromolecules. 2003;36:5602–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boots H, Kloosterboer J, Serbutoviez C, Touwslager F. Polymerization-induced phase separation. 1. Conversion-phase diagrams. Macromolecules. 1996;29:7683–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nwabunma D, Chiu H-W, Kyu T. Morphology development and dynamics of photopolymerization-induced phase separation in mixtures of a nematic liquid crystal and photocuratives. Macromolecules. 2000;33:1416–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey BM, Hui V, Fei R, Grunlan MA. Tuning PEG-DA hydrogel properties via solvent-induced phase separation (SIPS). Journal of materials chemistry. 2011;21:18776–82. doi: 10.1039/C1JM13943F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shibayama M, Morimoto M, Nomura S. Phase separation induced mechanical transition of poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)/water isochore gels. Macromolecules. 1994;27:5060–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anseth KS, Wang CM, Bowman CN. Reaction behaviour and kinetic constants for photopolymerizations of multi (meth) acrylate monomers. Polymer. 1994;35:3243–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook WD. Photopolymerization kinetics of oligo (ethylene oxide) and oligo (methylene) oxide dimethacrylates. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 1993;31:1053–67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horie K, Otagawa A, Muraoka M, Mita I. Calorimetric investigation of polymerization reactions. V. Crosslinked copolymerization of methyl methacrylate with ethylene dimethacrylate. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Chemistry Edition. 1975;13:445–54. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Q, Nauman S, Santerre J, Zhu S. UV photopolymerization behavior of dimethacrylate oligomers with camphorquinone/amine initiator system. Journal of applied polymer science. 2001;82:1107–17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, Lee LJ. Photopolymerization of HEMA/DEGDMA hydrogels in solution. Polymer. 2005;46:11540–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park J, Ye Q, Topp EM, Misra A, Kieweg SL, Spencer P. Effect of photoinitiator system and water content on dynamic mechanical properties of a light-cured bisGMA/HEMA dental resin. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2010;93A:1245–51. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovell LG, Berchtold KA, Elliott JE, Lu H, Bowman CN. Understanding the kinetics and network formation of dimethacrylate dental resins. Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 2001;12:335–45. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Co kun M, Demirelli K, Ahmetzade MA. Synthesis, Characterization, and Polymerization of New Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate Containing Cyclobutane Ring. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A. 1997;34:429–38. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kopecek J. Hydrogels: From soft contact lenses and implants to self-assembled nanomaterials. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:5929–46. doi: 10.1002/pola.23607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park J, Ye Q, Singh V, Kieweg SL, Misra A, Spencer P. Synthesis and evaluation of novel dental monomer with branched aromatic carboxylic acid group. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2012;100B:569–76. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spencer P, Ye Q, Park J, Topp EM, Misra A, Marangos O, et al. Adhesive/Dentin Interface: The Weak Link in the Composite Restoration. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2010;38:1989–2003. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh V, Misra A, Parthasarathy R, Ye Q, Park J, Spencer P. Mechanical properties of methacrylate-based model dentin adhesives: Effect of loading rate and moisture exposure. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2013;101:1437–43. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hansel C, Leyhausen G, Mai UE, Geurtsen W. Effects of various resin composite (co)monomers and extracts on two caries-associated micro-organisms in vitro. J Dent Res. 1998;77:60–7. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leinfelder KF. Do restorations made of amalgam outlast those made of resin-based composite? J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:1186–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]