Abstract

Controlled delivery of angiogenic factor sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) represents a promising strategy for promoting vascularization during tissue repair and regeneration. In this study, we developed an amphiphilic biodegradable polymer platform for the stable encapsulation and sustained release of S1P. Mimicking the interaction between amphiphilic S1P and its binding proteins, a series of polymers with hydrophilic poly(ethylene glycol) core and lipophilic flanking segments of polylactide and/or poly(alkylated lactide) with different alkyl chain lengths were synthesized. These polymers were electrospun into fibrous meshes, and loaded with S1P in generally high loading efficiencies (>90%). Sustained S1P release from these scaffolds could be tuned by adjusting the alkyl chain length, blockiness and lipophilic block length, achieving 35-55% and 45-80% accumulative releases in the first 8 h and by 7 days, respectively. Furthermore, using endothelial cell tube formation assay and chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay, we showed that the different S1P loading doses and release kinetics translated into distinct pro-angiogenic outcomes. These results suggest that these amphiphilic polymers are effective delivery vehicles for S1P and may be explored as tissue engineering scaffolds where the delivery of lipophilic or amphiphilic bioactive factors are desired.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Drug delivery, Amphiphilic copolymer, Sphingosine-1-phosphate, Tissue engineering

1. Introduction

Angiogenesis is essential for tissue development, function, maintenance, repair and regeneration [1-5], and impaired angiogenesis due to either injuries or diseases can severely impair these processes. For instance, disruption of vascular network as a result of orthopedic trauma compromises the ability to vascularize bone grafts, resulting in high clinical failure rates of bone graft-mediated repair of traumatic bone defects [6]. In pathological conditions such as diabetes, the microangiopathic complication/tissue ischemia also retards bone injury repair and graft healing [7, 8] as it disrupts the tightly coupled osteogenesis and angiogenesis processes [9]. Therefore, therapeutic strategies for promoting angiogenesis, particularly the formation of functional and stable vascular network, have long been sought after in scaffold-assisted tissue repair and regeneration.

Angiogenesis is a dynamic cascade of cellular and molecular events [10, 11] involving early-stage of lumen formation (e.g. increased blood vessel permeability, basement membrane degradation, endothelial cell (EC) migration, proliferation and further assembly into tubular structure) and later-stage of nascent EC tube stabilization and maturation (e.g. mural cells recruitment and new basement membrane deposition). The entire angiogenesis process is tightly regulated by a dynamic balance of pro-angiogenic factors and vessel-stabilizing factors [12]. Current strategies for recapitulating this process in-situ [5, 13, 14] involve the delivery of angiogenic stimuli, of which angiogenic growth factor such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the most intensively studied [15-17]. VEGF is a potent angiogenesis initiator that is also known to disrupt pericyte coverage and inhibit subsequent vessel stabilization [18], thus the delivery of exogenous VEGF alone often results in sub-optimal neovascularization characterized with immature “leaky” vessels. Therefore, the delivery of alternative/complementary signaling molecules promoting the formation of more extensive, stable and functional vascular network are highly desired. Phospholipid sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) has emerged as such a promising candidate because of its dual role as angiogenic stimulant and blood vessel stabilizer.

During the early stages of angiogenesis, S1P acts as a potent EC chemoattractant [19, 20], promoting EC proliferation, migration [21] and further assembly into tubes [22] while S1P receptor 1 (S1P1) negatively regulates vessel sprouting to prevent excessive sprouting [23, 24]. In the later stages of angiogenesis, S1P regulates vasculature remodeling and maturation by recruiting vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) and pericytes [25-28]. The local delivery of S1P or S1P analogue FTY 720 has been shown to enhance wound healing in diabetic rats [29], stimulate blood flow in ischemic limbs [30], and promote calvarial bone formation [31-33] and allograft incorporation [34, 35]. These studies support potential benefits of the delivery of S1P in improving the functional outcome of tissue repair.

A significant challenge for translating the S1P-based proangiogenic strategy to successful tissue repair is, however, the lack of a tunable sustained release system enabling the optimization of its release kinetics for maximal stimulation of vessel formation and maturation. Scaffolds being explored for S1P encapsulation include hydrophobic poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) thin films [31, 32]/microspheres [30] and hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels cross-linked by albumin [36]. While some of these scaffolds exhibited acceptable S1P loading efficiency, their intrinsic structures have limited direct interactions with the amphiphilic S1P, thus the tunability of S1P release kinetics. Recently a cellulose hollow fiber-based system enabling timed delivery of S1P following earlier release of VEGF was shown to result in greater recruitment of ECs and higher maturation index of formed vessels in a Matrigel plug model [37]. However, this delivery system required external manual regulation, which complicates its implementation for in vivo tissue regeneration. Overall, synthetic scaffolds demonstrating significantly improved S1P loading efficiency and more tunable S1P release kinetics is still lacking.

Structurally, S1P is an amphiphilic lysophospholipid comprised of a zwitterionic headgroup and a hydrophobic 18-carbon (C18) aliphatic tail. In circulating blood, S1P is released from platelets [38] in micromolar concentrations and most of the released S1P is stored by binding with albumin [20, 39] and lipoproteins such as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [40, 41]. Recent structural studies revealed that the interaction of S1P with HDL is mediated by HDL-associated apolipoprotein M (apoM). Specifically, apoM was shown to have an amphiphilic binding pocket with a polar entrance to grab the hydrophilic S1P headgroup and an inner lipophilic pocket to accommodate the C18 aliphatic tail [42, 43]. This amphiphilic interaction pattern is also observed with the bindings of S1P antagonist with S1P1 receptor [44] and S1P with S1P antibody [45]. Mimicking this interaction, here we hypothesize that an amphiphilic polymer scaffold incorporating both hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments could effectively bind S1P, translating into improved S1P loading efficiency. Furthermore, the release kinetics of the encapsulated S1P could possibly be tuned by adjusting the lipophilicity of the polymer. In this study, we test these hypotheses with a PLA-PEG-PLA (PELA)-based amphiphilic block copolymer platform [46] by incorporating alkylated lactides. By varying alkyl side chain lengths, blockiness and block lengths, we examine their impact on the encapsulation, release and angiogenic outcome of S1P delivery using a combination of EC tube formation assay and ex vivo chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and general instrumentation

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Growth factor reduced Matrigel was obtained from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA). Fertile chicken eggs were supplied by Charles River Labs (Wilmington, MA). All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and used as received unless otherwise stated. 2-Hydroxyhexadecanoic acid was synthesized from 2-bromohexadecanoic acid per literature protocols [47].

NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA-400 spectrometer. Molecular weights and polydispersity of polymers were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) on a Varian Prostar HPLC system equipped with two 5-mm PLGel MiniMIX-D columns and a PL-ELS2100 evaporative light scattering detector. Calibrations were performed with polystyrene standards (polymer laboratories). THF was used as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min.

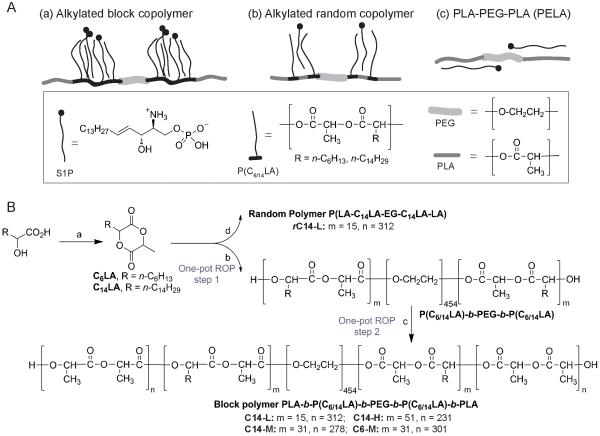

2.2. Design rationale of the amphiphilic polymers and alkylated lactide monomers

PLA-PEG-PLA (PELA)-based amphiphilic copolymer-based platform is designed to enable interactions between the polar S1P headgroup and the hydrophilic PEG segment, as well as the lipophilic S1P tail with the hydrophobic PLA blocks. By inserting alkylated polylactides to PELA either in discrete blocks between the PEG core and the PLA ends or randomly with the PLA blocks, we hope to further enhance S1P binding via hydrophobic interactions between the aliphatic side chains and the S1P lipid tail (Fig. 1A). It is worth noting that complete elimination of PLA from the amphiphilic copolymers (i.e. substituting two PLA blocks in PELA with alkylated polylactides) tended to result in copolymers with lower molecular weight liquids (Table S1) that are unsuitable for electrospinning fabrication of bulk scaffolds. Three distinct design elements were altered to allow the scaffolds to interact with S1P with varied affinities: the alkyl side chain lengths (C6 vs. C14), distribution (random copolymers with alkyl side chains spreading out vs. block copolymers with the alkyl side chains more densely clustered), and presentation density (low, medium and high alkylated repeating units relative to PEG core).

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of possible interactions between S1P and the amphiphilic polymers. (B) Synthetic schemes for the alkylated lactides and amphiphilic polymers. Reagents and conditions: (a) 2-bromopropionyl bromide (1.05 eq.), Et3N (2.0 eq.), acetone, rt for 0.5 h, then filtered; Et3N (2.0 eq.), 65 °C for 2 h. (b) PEG20K, Sn(Oct)2, 150 °C, 30 min. (c) D,L-lactide, 150 °C, 60 min. (d) PEG20K, D,L-lactide, Sn(Oct)2, 150 °C, 60 min.

The design of 3-methyl-6-alkyl-1,4-dioxane-2,5-diones as alkylated lactide monomers was motivated by their biocompatible degradation products, -hydroxyl fatty acids, that are present in plants and mammals [48, 49]. The choice of mono-instead of bi-alkylated lactides was due to the concern that the excessive steric hindrance of the latter that may compromise the ring-opening polymerization efficiency.

2.3. Monomer syntheses

2.3.1. 3-Methyl-6-hexyl-1,4-dioxane-2,5-dione (C6LA)

The monomer synthesis was carried out following a protocol modified over literature [47, 50, 51]. To an ice-bath chilled acetone solution (150 mL) of 2-hydroxyoctanoic acid (5.0 g, 31.21 mmol) and Et3N (8.71 mL, 62.42 mmol) was slowly added 2-bromopropionyl bromide (3.43 mL, 32.77 mmol). The white suspension was then stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h before it was filtered. The obtained white residue was further washed with acetone twice to give a combined light yellow filtrate of a total volume of 300 mL, to which was added Et3N (8.71 mL, 62.42 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 65 °C for 2 h before it was cooled to room temperature and concentrated to 50 mL under reduced pressure. The concentrate was filtered, further concentrated and diluted with a mixture of n-hexane and EtOAc (n-hexane/EtOAc = 3/1, 150 mL), and passed through a short silica gel column to give the crude product, which was recrystallized twice with n-hexane to yield a white solid racemic monomer (1.85 g, 27.7% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.02 (m, 1H), 4.90 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 2H), 1.67 (m, 3H), 1.61 (m, 2H), 1.52 (m, 6H), 0.88 (m, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.77, 167.15, 77.11, 76.03, 72.73, 72.48, 32.15, 31.68, 31.62, 30.23, 28.97, 28.74, 24.84, 24.52, 22.71, 22.68, 17.77, 16.07, 14.24, 14.21 ppm.

2.3.2. 3-Methyl-6-tetradecyl-1,4-dioxane-2,5-dione (C14LA)

The monomer C14LA was prepared in a similar fashion from 2-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid instead of 2-hydroxyoctanioic acid. Recrystalized racemic product (white solid) was obtained in a 43.1% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.01 (m, 1H), 4.89 (m, 1H), 2.02 (m, 2H), 1.68 (m, 3H), 1.52 (m, 2H), 1.30 (m, 22H), 0.87 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.71, 167.08, 77.13, 76.05, 72.49, 32.15, 30.26, 29.91, 29.90, 29.88, 29.87, 29.82, 29.79, 29.71, 29.67, 29.59, 29.53, 29.47, 29.33, 29.10, 24.90, 24.59, 22.92, 17.80, 16.10, 14.36 ppm.

2.4. Polymer syntheses

The synthesis of amphiphilic copolymers was conducted using one-pot ring opening polymerization (ROP) by sequential (for block copolymer) or simultaneous (for random copolymer) addition of the respective monomers. The polyethylene glycol (PEG, 20,000 Dalton) was dried by azeotropic distillation with toluene. The D,L-lactide was freshly purified by recrystallization with ethyl acetate twice. Catalyst stannous octoate, Sn(Oct)2, was prepared as a stock solution in anhydrous toluene, and added in equivalent molar ratio to PEG. The feeding ratio of D,L-lactide, C6LA or C14LA monomers to PEG varied based on the target polymer compositions as described in Table S1 and Table 1. 1H NMR spectra of intermediates and crude products were taken to ensure that the monomer conversions were >90% for each step. The yields and GPC characterizations (Mn, PDI) of the triblock and pentablock copolymers are summarized in Table S1 and Table 1.

Table 1.

Properties of amphiphilic pentablock and random copolymers

| Abbreviation | Polymer Composition a | C6/14LA: EG (mol: mol) |

Yield (%) | MnGPC | PDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding | Incorporated b | |||||

| Pentablock copolymers | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| C14-L | LA312-(C14LA)15-EG454-(C14LA)15-LA312 | 1 : 15.1 | 1 : 17.2 | 107,282 | 1.47 | |

| C14-M | LA278-(C14LA)31-EG454-(C14LA)31-LA278 | 1 : 7.3 | 1 : 8.3 | 86.9 | 79,687 | 1.51 |

| C14-H | LA231-(C14LA)51-EG454-(C14LA)51-LA231 | 1 : 4.4 | 1 : 5.4 | 90.2 | 66,963 | 1.55 |

| C6-M | LA301-(C6LA)31-EG454-(C6LA)31-LA301 | 1 : 7.3 | 1 : 7.2 | 88.9 | 81,059 | 1.48 |

|

| ||||||

| Random copolymer | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| rC14-L | LA312-(C14LA)15-EG454-(C14LA)15-LA312 | 1 : 15.1 | 1 : 19.0 | 88.0 | 69,251 | 1.49 |

Subscripts refer to the number of repeating units for the respective blocks.

Based on 1H NMR integration ratio of the (CH2CH2O) signal from the PEG to the terminal CH3 signal from the C14 or C6 aliphatic side chains.

2.4.1 Pentablock copolymer PLA312-b-P(C14LA)15-b-PEG454-b-P(C14LA)15-b-PLA312 (C14-L)

PEG (600 mg, 0.03 mmol) and C14LA (300 mg, 0.92 mmol) were combined in a Schlenk vessel (10 mL), which was dried at 150 °C for 0.5 h under vacuum. After being cooled to room temperature, the reaction vessel was purged with argon, and Sn(Oct)2 solution (0.03 mmol) was added and the solvent was evaporated. The mixture was heated at 150 °C for 0.5 h to allow polymerization of the alkylated lactide, followed by the addition of D,L-lactide (2700 mg, 18.73 mmol) under argon. The melt mass was allowed to polymerize at 150 °C for another 1 h before it was quenched by exposure to air at room temperature. The crude product was purified by dissolving in chloroform and precipitating in ice-cold methanol. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.17 (m, 90H), 3.64 (s, 138H), 1.51 (m, 345H), 0.87 (t, J = 6.80 Hz, 6H) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.81, 169.62, 169.56, 169.52, 169.34, 70.77, 69.39, 69.20, 32.14, 29.93, 29.59, 22.91, 16.96, 16.89, 14.35 ppm.

2.4.2. Pentablock copolymer PLA278-b-P(C14LA)31-b-PEG454-b-P(C14LA)31-b-PLA278 (C14-M)

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.18 (m, 38H), 3.64 (s, 66H), 1.54 (m, 179H), 0.87 (t, J = 6.80 Hz, 6H) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.81, 169.56, 169.34, 70.78, 69.39, 69.20, 32.15, 29.93, 29.59, 22.91, 16.97, 16.89, 14.35 ppm.

2.4.3. Pentablock copolymer PLA231-b-P(C14LA)51-b-PEG454-b-P(C14LA)51-b-PLA231 (C14-H)

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.17 (m, 26H), 3.63 (s, 43H), 1.54 (m, 147H), 0.87 (t, J = 6.80 Hz, 6H) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.81, 169.56, 169.53, 169.34, 70.78, 69.39, 69.20, 32.14, 29.93, 29.89, 29.59, 22.91, 16.95, 16.89, 14.34 ppm.

2.4.4. Pentablock copolymer PLA301-b-P(C6LA)31-b-PEG454-b-P(C6LA)31-b-PLA301 (C6-M)

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.15 (m, 38H), 3.63 (s, 58H), 1.58 (m, 155H), 0.86 (t, J = 6.80 Hz, 6H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.83, 169.62, 169.55, 169.53, 169.34, 70.76, 69.38, 69.19, 31.70, 22.72, 16.94, 16.87, 14.23 ppm.

2.4.5. Random copolymer P[LA312-(C14LA)15-EG454-(C14LA)15-LA312] (rC14-L)

PEG (600 mg), C14LA (300 mg) and D,L-lactide (2700 mg) were combined in a Schlenk vessel, and dried at 150 °C under vacuum for 0.5 h. The Sn(Oct)2 solution (0.03 mmol) was then added and the solvent was evaporated. The mixture was allowed to polymerize under argon at 150 °C for 1 h. The polymerization was quenched by exposure to air at room temperature and purified by dissolving in chloroform and precipitating in ice-cold methanol. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.17 (m, 93H), 3.63 (s, 152H), 1.54 (m, 370H), 0.87 (t, J = 6.80 Hz, 6H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.83, 169.56, 169.35, 70.75, 69.38, 69.19, 32.12, 29.89, 29.56, 22.89, 16.95, 16.88, 14.34 ppm.

2.4.6. Triblock copolymer PLA347-PEG454-PLA347 (PELA)

PEG (1000 mg, 0.05 mmol) and D,L-lactide (5000 mg, 34.69 mmol) were combined in a Schlenk vessel and dried under vacuum for 0.5 h. The mixture was allowed to polymerize at 150 °C for 45 min, following the addition of Sn(Oct)2 solution (0.05 mmol) under argon. The polymerization was quenched and the polymer was purified as described above. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.17 (m, 3.87H), 3.64 (s, 5.77H), 1.55 (m, 12H) ppm.

2.5. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis

The DSC analysis was carried out on a Q200 Modulated DSC (TA Instruments), which was calibrated with indium and sapphire standards prior to use. Under nitrogen atmosphere, each specimen (10 mg) was heated at a rate of 10.00 °C/min from −90 °C to 150 °C, then cooled to −90 °C at the same rate before being heated back to 150 °C. Thermal transitions detected during the second heating cycle were used for data interpretation.

2.6. Mesh fabrication by electrospinning

The dried polymers were dispersed in a mixed solvent of chloroform and D,D-dimethylformamide (4:1 v/v) at a concentration of 25% (w/v) overnight. The polymers were electrospun into fibrous meshes by ejecting respective polymer solution through a blunt 22 gauge needle at a rate of 1.7 mL/h under 12 kV to a grounded Al-receiving plate set at 15 cm apart from the needle tip. 1H NMR analysis of the mesh dissolved in CDCl3 confirmed that there was no detectable residue D,D-dimethylformamide. The meshes were further dried in house vacuum overnight.

2.7. Scanning electronic microscopy (SEM)

The dried meshes were sputter coated with 4-nm gold and imaged on a Quanta 200 FEG MKII scanning electron microscope (FEI Inc., Hillsboro, OR) under high vacuum at 5 kV. The average fiber diameter was quantified from 50 randomly selected fibers in the micrograph acquired under 1000× magnification using ImageJ (NIH).

2.8. Fabrication of dense polymer films by solvent casting

In a typical procedure, the respective polymer (200 mg) was first dissolved in chloroform (4 mL) to obtain a clear solution, which was then cast into a 40 mm × 70 mm rectangle Teflon mold. The solvent was allowed to evaporate at room temperature overnight before the casted film was further dried under house vacuum and lifted off from the mold.

2.9. Water contact angle measurements

The water contact angle was determined with the sessile drop technique on a CAM 200 goniometer (KSV Instruments, Finland) connected with a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. Deionized water droplets were deposited on the surface of electrospun or solvent-cast specimen. The contact angles from left and right side of each droplet were recorded at 30 sec following the initial water contact. Seven measurements from 3 specimens were taken for each electrospun mesh type and ten measurements were taken for each solvent-cast film.

2.10. Mesh porosity determination

To determine the porosity of the electrospun mesh, circular specimens of the same diameter (6.3 mm; n = 3) were cut from electrospun meshes and the respective solvent-cast films using a puncher. The porosity (%) of each mesh was calculated based on its weight relative to that of the solvent-cast film, adjusted by their respective thickness measured by a digital caliper: porosity (%) = [1- (Weight mesh × thickness film) / (weight film × thickness mesh)] × 100%.

2.11. S1P loading

The electrospun meshes were punched into circles of 6.3 mm in diameter, weighed and sterilized with UV irradiation (254 nm, 1 h for each side). Fresh S1P solutions in PBS were carefully loaded onto each mesh (for S1P release study: 5 μL of 0.76-μg/μL solution to achieve 3.8-μg S1P loading per mesh; for tube formation assay: 2 or 10 μL of 0.19-μg/μL solution to achieve 0.38-μg or 1.90-μg S1P loading per mesh). The S1P-loaded meshes were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and 4 °C for another 4 h before they were air-dried in laminar flow hood overnight.

For CAM assay, pre-hydrated meshes were lyophilized, UV-sterilized, cut into circles of 3 mm in diameter and loaded with 0.5-μg S1P (1 μL of 0.5-μg/μL S1P solution in PBS) per mesh. The S1P-loaded meshes were then incubated and air-dried as described above.

2.12. S1P release

The S1P-loaded specimens (n = 3) were placed in 200 μL of PBS solution containing 0.2% fatty acid-free-bovine serum albumin (FAF-BSA) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. FAF-BSA was added to stabilize the released S1P and prevent them from aggregating to ensure their detection by ELISA. We showed that in the absence of BSA, S1P standards became less detectable by ELISA. With the supplementation of 0.2% or 0.4% BSA, S1P standard remained consistently detected by ELISA. Thus, 0.2% FAF-BSA was chosen for the release study. At specific time points (5 min, 8 h, 1, 3, 5 and 7 days), the release solutions were collected, and fresh PBS solution with 0.2% FAF-BSA was added for continued incubation. The collected solutions were stored at −80°C until time of quantification. The released S1P concentration was quantified using a sphingosine 1 phosphate assay kit (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT) following the vendor’s instruction. The S1P loading efficiency (%) was calculated as: (initial S1P loading - released S1P at 5 min) / initial S1P loading × 100%

2.13. Tube formation Assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, ATCC, passage 6), were cultured on gelatin-coated plates in M199 medium with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 3 ng/mL bFGF, 5 units/mL heparin and 100 U/100 μg/mL Pen/Strep at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The 96-well culture plate was coated with 50 μL/well growth factor reduced Matrigel and incubated at 37 °C for 0.5 h to allow Matrigel to solidify. Then HUVECs suspended in 100 μL of M199 medium with 0.1% FBS and 100 U/100 μg/mL Pen/Strep were seeded on the Matrigel at 2 × 104 cells/well. After 30 min of cell attachment, PBS solutions of S1P or S1P-loaded meshes were carefully added to each well, followed by continued incubation at 37 °C for 17 h. After removing the meshes and culture media, the HUVECs were fixed with 10% formalin saline solution and imaged with an Axiovert 40 CFL microscope equipped with a QImaging camera at 25× and 100× magnifications. The total tube length in each well (n = 3-4) was quantified by ImageJ (NIH).

2.14. Chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay

An ex-ovo CAM assay was used to examine the pro-angiogenic effects of S1P-loaded meshes. Briefly, fertile chicken eggs were incubated blunt side up at 37 °C in 70% humidity for 3 days, and rotated three times daily. Then the eggs were wiped with 70% ethanol, carefully cracked into 100-mm Petri dishes, and incubated for another 7 days. Sterilized circular meshes loaded with 0.5-μg S1P or PBS control were carefully placed on the CAM, and the embryos were cultured for 3 more days. The morphology of blood vessels surrounding the implants was photo-documented via a stereomicroscope by a digital camera (DFC 295, Leica) at 16× magnification. The CAM surrounding the mesh was then fixed with 10% formalin solution in PBS, flipped, and imaged at 25× magnification.

2.15. Data analysis

All quantitative data are plotted as mean ± standard derivation. Student’s t-tests were employed for statistical analysis. Significance level was set as p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of alkylated monomers and amphiphilic copolymers

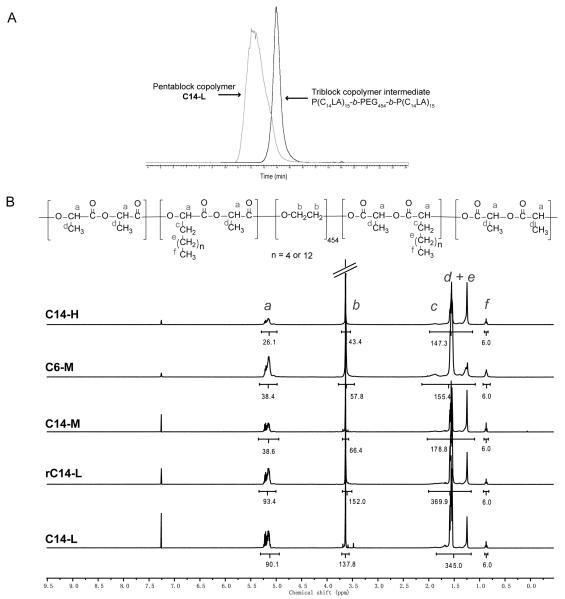

The mono-alkylated lactides C6LA and C14LA were prepared using a two-step process (Fig. 1B) with an overall moderate yield (largely limited by the intramolecular condensation step) that is consistent with literature. With a targeted molecular weight of 120 kD for all pentablock and random copolymers, melt ROP using PEG20K as a macromolecular initiator and Sn(Oct)2 as catalyst (Fig. 1B) was carried out by simultaneous (for random polymer) or sequential (for block copolymers) addition of alkylated lactides and D,L-lactide (Fig. 1B). PELA of the same targeted molecular weight was also prepared. All polymers were obtained in good yields with high monomer conversions (>90%) and reasonable molecular weight distributions, with PDI of 1.1-1.2 for most triblock copolymers (Table S1) and 1.4-1.5 for pentablock copolymes (Table 1). Decreased number-average molecular weights were observed for triblock copolymers containing increasing theoretical lengths of C14-alkylated blocks (Table S1). GPC comparison of a typical triblock intermediate and final crude pentablock product supported the narrow molecular distributions and high conversions (Fig. 2A). 1H NMR integration also supported an overall excellent (80-100%) incorporation of alkylated monomers (Fig. 2B and Table 1). It appeared to be more challenging to obtain high molecular weight random copolymers than the block copolymers (e.g. MnGPC of rC14-L was 1.5-fold lower than that of the C14-L of same targeted molecular weights).

Figure 2.

(A) GPC chromatograms of triblock copolymer intermediate P(C14LA)15-b-PEG454-b-P(C14LA)15 (Mn = 34,653, PDI = 1.13) and crude pentablock copolymer PLA312-b-P(C14LA)15-b-PEG454-b-P(C14LA)15-b-PLA312 (C14-L, Mn = 113,463, PDI = 1.47). (B) 1H NMR spectra of the pentablock and random copolymers.

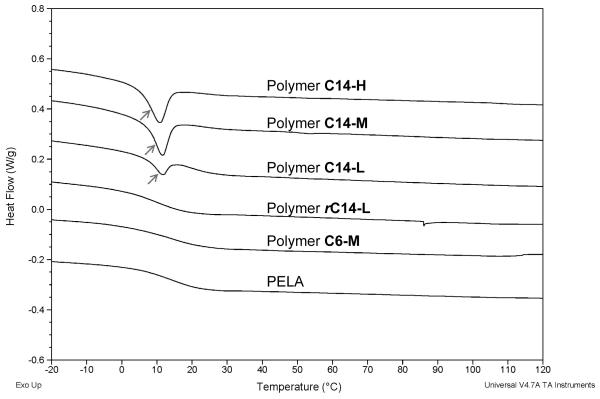

The thermal properties of polymers were examined by DSC to reveal hydrophobic chain-chain interactions, characterized by a thermal transition associated with the aggregation and disassociation of the alkylated side chains. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure S2, an endothermic peak at 10.86 °C, 11.63 °C and 11.75 °C was detected for C14-alkylated pentablock copolymer C14-H, C14-M and C14-L, respectively, supporting the hydrophobic chain-chain interactions within these amphiphilic pentablock copolymers. However, no such thermal transition was detected in PELA, short chain polymer C6-M or random polymer rC14-L. This thermal transition was also observed in the C14-triblock polymers, but not in the C6-triblock copolymer or PELA (Fig. S1), besides the major endothermic peak at 55-65 °C attributable to PEG crystallization/melting [46].

Figure 3.

DSC spectra of PELA, pentablock and random copolymers.

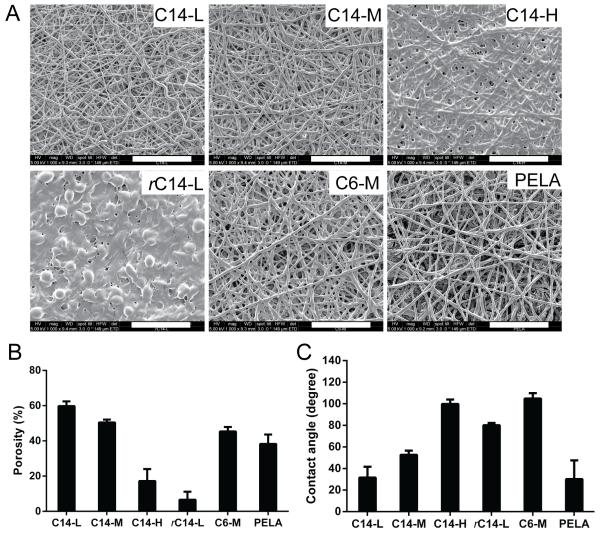

3.2. Polymer fibrous mesh fabrication and characterization

The amphiphilic polymers were electrospun into fibrous meshes. As shown in Figure 4A, PELA, C6-M, C14-L and C14-M meshes were composed of randomly arranged microfibers free of beading, with an average fiber diameter of 1.76 ± 0.25 μm, 2.03 ± 0.60 μm, 1.18 ± 0.46 μm and 1.66 ± 0.37 μm, respectively. High-content alkyl side chain incorporation as in the case of C14-H resulted in partial fusion of the fibers, likely driven by hydrophobic interactions between the alkylated segments of contacting fibers at the ambient temperature. The random copolymer rC14-L mesh did not exhibit distinctive fiber morphology, but rather appeared to be composed of fused beading structures, suggesting that this copolymer did not possess optimal physical characteristics (e.g. viscosity) for electrospinning. The quantification of porosity of the electrospun meshes relative to the respective dense solvent-cast films by weight (Fig. 4B) revealed the highest porosity (~60%) for the C14-L mesh, 40-50% porosity for the C14-M, C6-M and PELA meshes, whereas <20% and <10% porosity for C14-H and rC14-L, consistent with the morphologies revealed by SEM micrographs (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) SEM micrographs, (B) calculated mesh porosity (by methods described in section 2.10; n = 3) and (C) water contact angles (n = 7) of electrospun fibrous meshes. Scale bar = 50 μm.

To examine how the varying surface morphology/porosity and intrinsic hydrophilicity of the polymers translate into differential water wettability, the water contact angles of both electrospun meshes and the respective dense solvent-cast films were measured. Among all dense solvent-cast films (Fig. S3), PELA and rC14-L exhibited significantly lower water contact angle than others, suggesting relatively higher hydrophilicity for PELA and rC14-L. The difference in water contact angles among the dense C14-L, C14-M and C14-H solvent-cast film, however, was not dramatic. The electrospun C14-L, C14-M and C14-H meshes, on the other hand, exhibited significant increases in water contact angles (Fig. 4C), accompanying the decreasing porosity of these electrospun fiber meshes (Fig. 4B), as the content of C14-alkyl side chains increased, supporting significant contributions of surface porosity to the water wettability of the meshes. Overall, C14-L and PELA meshes were the most wettable by water (contact angles ~30°), while the C14-H and C6-M meshes were the least wettable among all (water contact angle ~100°). The least porous (<10%) yet one of the most hydrophilic (Fig. S3) rC14-L electrospun mesh exhibited a water contact angle (~80°) between that of C14-H and C14-M meshes, supporting that surface porosity and polymer hydrophilicity synergistically contribute the overall wettability of the fibrous mesh.

3.3. In-vitro S1P loading and release

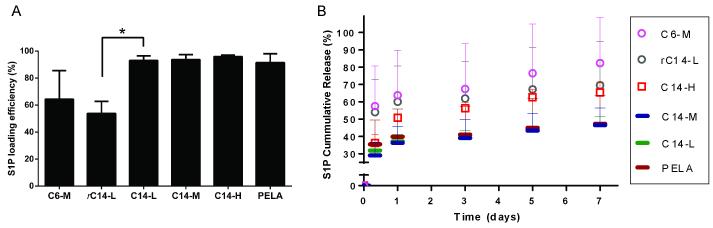

The S1P loading efficiency and release profile were determined using S1P competitive ELISA (R2 = 0.970 for standard curve). As shown in Figure 5A, the S1P loading efficiencies for PELA and C14-alkylated block copolymer meshes, determined as the percentage of S1P retained on the meshes after 5-min incubation in PBS with 0.2% FAF-BSA, were all above 90%, while the rC14-L and C6-M meshes displayed a much lower loading efficiency of 64% and 54%, respectively.

Figure 5.

(A) S1P loading efficiencies (n = 3) on polymeric fibrous meshes and (B) their cumulative releases over time (n = 3) in PBS with 0.2% FAF-BSA.

The percentages of cumulative release of S1P at various time points were determined relative to the amount retained on the respective meshes at 5 min. As shown in Figure 5B, mesh rC14-L exhibited similar S1P early release kinetics as C6-M while meshes C14-L, C14-M shared similar profiles as that of PELA. However, in consideration of its inferior electrospinability (e.g. tendency to bead) and poor S1P loading efficiency, the random copolymer rC14-L was deemed unsuitable for S1P delivery and excluded from further investigations in the current study. Among the rest of the electrospun meshes, C6-M released significantly more S1P (~55%) than C14-block copolymer (C14-L, -M, -H) or PELA meshes (30-35%) during the first 8 h, followed by a slower yet continuing release (Fig. 5B). A total of ~80% S1P was released from C6-M, ~65% from C14-H, and ~45% from PELA and C14-M by day 7 was accomplished (Fig. 5B).

Overall, PELA, C14-L and C14-M (Fig. 5B, bar symbols) exhibited the slowest releases over 7 days, C14-H exhibited the most sustained release (Fig. 5B, square symbols), while C6-M led to a higher burst release of S1P (Fig. 5B, circle symbols). Among the alkylated copolymers well-suited for electrospinning, C14-M, C14-H and C6-M were thus chosen for further investigation as to whether/how the three distinctive release profiles may translate into differential in vitro angiogenic outcomes by tube formation assays. Given the unalkylated nature, the PELA mesh, although with similar S1P release profile as C14-M, was also included in the tube formation assay.

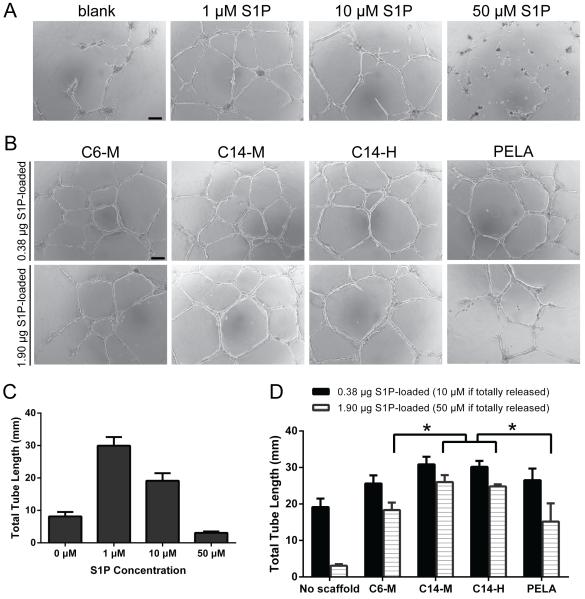

3.4. Tube formation assay

HUVEC tube formation assay was employed to evaluate the pro-angiogenic activity of released S1P in vitro [52]. We first showed that in the absence of a polymer carrier, the total tube length increased with the direct supplement of 1-μM S1P, however, such proangiogenic effect was compromised at the higher concentration of 10-μM S1P. Furthermore, the direct exposure of HUVEC-Matrigel culture to a very high concentration of 50-μM S1P significantly inhibited tube formation (resulted from a dramatic inhibition of cell mobility) compared to no-S1P control (Figs. 6A and 6C).

Figure 6.

Representative micrographs and total tube length quantifications (n = 3-4) of HUVEC-Matrigel cultures after 17 h exposure to free S1P solutions of varying concentrations (A & C) or polymer meshes preloaded with varying doses of S1P (B & D). Scale bar = 100 μm.

When S1P was delivered via the amphiphilic polymer scaffolds, more robust and uniform tube formations were observed. When S1P was loaded on C14-alkylated copolymer meshes at a dose equivalent to 10-μM upon 100% release, total tube lengths observed were equivalent to that observed upon supplementation of 1-μM free S1P (Figs. 6B and 6D). This observation supports that the amphiphilic polymer scaffolds effectively prevented the burst-release of high doses of S1P that could have been inhibitory to tube formations, with the C14-alkylated (C14-M) slightly more effective than the C6-alkylated counterpart (C6-M) or PELA. The benefit of slower and more sustained releases of S1P from C14-alkylated copolymer (C14-M & C14-H) meshes were more profoundly reflected when a higher loading dose of S1P was applied (equivalent to 50-μM S1P upon 100% release). The total tube length observed was longer than those stimulated with 10-μM free S1P. The C6-M and PELA meshes preloaded with the same high-dose S1P resulted in significantly shorter total tube lengths, although still comparable to that observed with the culture supplemented with 10-μM free S1P.

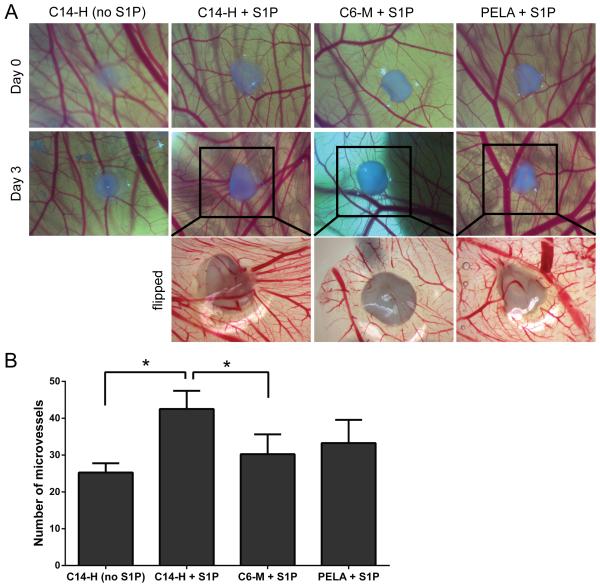

3.6 Ex-ovo chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay

To further explore the effect of S1P release kinetics on angiogenesis over a longer period (several days as opposed to 17 h in the HUVEC tube formation assay), three S1P-bearing amphiphilic groups (PELA, C6-M and C14-H) with distinct S1P release kinetics were subjected to the ex-ovo CAM assay. As representatively shown in Figure 7A (top and middle row), the S1P-loaded C14-H group induced the most noticeable shift of surrounding vessels towards the implant. This is also accompanied by the most pronounced neovessle growth observed with the group implanted with S1P-loaded C14-H mesh, as supported by the quantification of total microvessels surrounding the implants (Fig. 7B). In comparison, S1P-bearing C6-M meshes, which led to more burst early release of S1P than C14-H, induced less potent neovessel growth (Fig. 7B). The morphologies of the neovessels beneath the meshes were more clearly visualized from the flipped CAM images (Fig. 7A, bottom row; note that the flipped image for C14-H without S1P was not shown as the CAM was damaged during the “flipping” process).

Figure 7.

Ex-ovo angiogenic effects of amphiphilic polymer meshes preloaded with 0.5-μg S1P examined by CAM assay. (A) Representative photographs of the CAM surrounding the meshes with/without S1P (16× mag.) at day 0 and day 3, and the photographs of the flipped side of the harvested CAM on day 3 (25× mag.) of the boxed area. (B) Quantification of microvessel numbers surrounding each scaffold (n = 4).

4. Discussion

Angiogenesis is dynamically regulated by a number of angiogenic factors. Recapitulating their temporal and dose control in the delivery of exogenous angiogenic factors to stimulate tissue repair represents a significant challenge. The amphiphilic polymers reported in this study represent a biomimetic strategy to realize S1P immobilization and tunable sustained release through reversible amphiphilic interactions. These polymers were synthesized with conventional ROP and electrospun into fibrous meshes. Three C14-alkylated pentablock copolymers (C14-H, C14-M, C14-L) containing high, medium and low C14-block lengths relative to the hydrophilic PEG core, one C6-alkylated pentablock copolymer (C6-M) containing medium C6 block length, one C14-alkylated random copolymer (rC14-L), and the triblock copolymer PELA without alkyl side chains were subjected to detailed comparative studies.

Thermal analysis of the amphiphilic polymers by DSC revealed an endothermic peak at 10-12 °C ascribable to alkyl-alkyl aggregations in C14-block polymers, but not in the C6-block or C14-random copolymers (Fig 3). These observations suggest that adequate interactions between clustered (blocky) alkyl side chains of critical length is required for creating the hydrophobic “pocket” desired for trapping the lipid tail of S1P. SEM micrographs of the electrospun meshes (Fig 4A) and the porosities calculated from the weight ratios of the porous meshes to the dense films (Fig 4B) revealed varying fiber morphologies and porosities. While the C6-M, C14-M, C14-L and the unalkylated PELA meshes were characterized with medium (40-60%) porosity and well-defined fibers free of beading, the electrospun C14-H fibers exhibited some degrees of fusing, resulting in lower porosity (<20%). The random polymer rC14-L was unsuited for electrospinning, resulting in low-porosity (<10%) meshes lacing well-defined fiber morphology. The differential porosities, in combination with the intrinsic hydrophilicity of the amphiphilic copolymers as reflected by the water contact angles of the dense solvent-cast films (Fig S3), translated into significant differences in the wettability of the electrospun meshes (Fig. 4C).

The S1P loading efficiency and release kinetics was governed by both the thermal and physical properties of the alkylated amphiphilic polymer meshes. At room or body temperature, the intramolecular alkyl-alkyl aggregation is expected to undergo a dynamic equilibrium of association and disassociation, allowing S1P to be reversibly sequestered/released from the aggregated hydrophobic “pocket”, a characteristic desired for controlled and sustained release of S1P. Indeed, dynamic hydrophobic interactions appeared to have played a prominent role than the mesh porosity in ensuring high S1P loading efficiency with block copolymers with longer alkyl side chains (Fig. 5A, >90% loading efficiency for C14-L, C14-M and C14–H vs. ~55-65% for C6-M and rC14-L). The relatively low mesh porosity and wettability of C14-H electrospun mesh did not compromise its ability to support high S1P loading efficiency. The differential hydrophobic interactions between these amphiphilic alkylated polymers and S1P (Fig. 1A) also translated into distinct S1P release profiles (Fig. 5B). The less effective sequestering of S1P by the C6-M and rC14-L resulted in more rapid early release (~55% in the first 8 h) followed by substantial continued release (70-80% cumulative release in 7 days). C14-H displayed the most sustained and steady release of S1P, amounting to 35% in the first 8 h and 65% accumulative release by day 7. C14-M and C14-L exhibited very similar, and the slowest S1P release, totaling 30-35% in the first 8 h but no more than 10% additional S1P release in the next 7 days. The more substantial S1P release from mesh C14-H than those from C14-M or C14-L could in part be a result of its relatively low porosity (Fig. 4B) which may have resulted in S1P encapsulation more towards the surface (thus easier release). It is worth noting that due to the varying S1P loading methods, releasing conditions, detection methods adopted by literature reports [30, 34, 36], direct quantitative comparison of the S1P loading efficiency and release kinetics with literature carriers is difficult, although the high loading efficiency accomplished with our C14-alkylated system was excellent.

Interestingly, PELA displayed S1P loading and release kinetics similar to those of alkylated polymers C14-L and C14-M, despite its lack of alkylated side chains. One possible explanation may be that the amphiphilic PELA binds S1P through different mode of molecular interactions. We previously reported [46] that PELA could undergo a conformation rearrangement upon contact with water, exposing the hydrophilic PEG blocks to the polymer/water interface. Such a hydration-induced structural rearrangement may strengthen the hydrophobic interaction between its PLA blocks and the lipid tail of the S1P. For the alkylated amphiphilic copolymers, the mobility of the PLA segments may have been hindered due the steric constraints imposed by the aliphatic side chains, thereby minimizing S1P sequestration through this mechanism. This was supported by the differential changes in water contact angles of the amphiphilic meshes upon 24-h hydration (Fig. S4). Unlike PELA which exposed its hydrophilic PEG segments upon prior hydration to result in significant reduction in water contact angles [46], the alkylated amphiphilic polymers exhibited similar or slightly higher water contact angles, supporting that their PEG segments did not effectively expose to surface upon hydration.

The benefit of sustained delivery of S1P via a suitable scaffold was demonstrated in HUVEC-Matrigel tube formation assay and CAM assay. Unlike high doses (e.g. 50 μM) of free S1P solution that could pose inhibitory effect on tube formation [53], the same dose of S1P, when encapsulated/released by amphiphilic scaffolds, promoted EC tube formations. Such a benefit was more pronouncedly manifested by the C14-H and C14-M scaffolds than the C6-M mesh, which exhibited most rapid early release of S1P. Using a 3-day ex ovo CAM assay, we further demonstrated that C14-H mesh, with more sustained S1P release kinetics, led to significantly more neovessel formation and capillary bending/infiltration than the C6-M mesh. Collectively, these observations support that controlled S1P release can be functionally translated into pro-angiogenic activities both in vitro and ex ovo.

The tunable S1P loading efficiency, release profile, and in vitro and ex ovo pro-angiogenic activities enabled by the amphiphilic copolymer platform presented in this study provides a unique opportunity for optimizing angiogenesis for tissue repair/regeneration. Recently, we demonstrated superior aqueous stability, tensile elasticity, osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties of the bone mineral composites of amphiphilic copolymer PELA compared to those based on the hydrophobic PLA [46]. These benefits, likely retained with the amphiphilic copolymer platform presented here, may be combined with the controlled S1P delivery to synergistically promote osteogenesis and angiogenesis, thereby improving the outcome of scaffold-assisted bone repair. However, the in vivo efficacy of such a strategy will need to be rigorous examined using suitable animal models.

5. Conclusion

Emulating the amphiphilic interactions of angiogenic lipid S1P with its natural binding proteins, we developed an electrospun amphiphilic degradable copolymer platform for high-efficiency S1P loading and sustained release. By incorporating alkylated polylactides with 6- or 14-carbon side chains to amphiphilic triblock copolymer PLA-PEG-PLA (PELA) in varying spatial distributions (block vs. random) and clustering densities (high, medium and low), we demonstrated that S1P release profiles can be tuned. In general, alkylated random copolymers were found to exhibit inferior electrospinability and S1P loading efficiency (~50% vs. >90%) compared with the block copolymers. Furthermore, C6-alkylated block copolymers were found to lead to more rapid early release of S1P (55% in 8 h and 80% in 7 days) comparing with C14-alkylated block copolymers. More sustained and steady release of S1P (35% in 8 h and 65% in 7 days) was accomplished with the C14-block copolymer with long alkylated block length. Much slower release (30-35% in 8 h and 45% in 7 days) was observed with C14-alklyated block copolymer with medium alkylated block length and the unmodified PELA. The interactions between the alkylated amphiphilic copolymers and the S1P appeared to be primarily governed by the tendency of the alkylated side chains and the S1P lipid tail to aggregate (with longer alkyl chains and higher clustering density being more effective in sequestering S1P). By contrast, in the absence of the alkylated side chains, enhanced aggregation of the hydrophobic PLA blocks of PELA upon hydration may be a more dominant factor for the hydrophobic encapsulation of S1P. These distinctive S1P release profiles also translated into varying pro-angiogenic effects in vitro (HUVEC tube formation assay) and ex ovo (CAM assay) in a S1P dose-dependent manner. The benefit of more sustained release of S1P was clearly demonstrated with relatively high S1P encapsulation dose where high concentration of S1P resulting from their burst release could result in inhibitory rather than stimulatory effect on EC tube formations. CAM assay over three days confirmed the proangiogenic and chemotactic effect of S1P-bearing amphiphilic scaffolds. The C14-block copolymer mesh with longer alkylated block length, when encapsulated with S1P and placed on CAM, most effectively induced local neovessel formation and infiltration. Overall, this amphiphilic degradable copolymer platform represents a promising tool for mechanistic investigations of dose and temporal effects of S1P delivery on angiogenesis outcome. Furthermore, it can be exploited for controlled delivery of S1P and other hydrophobic or amphiphilic biomolecules for a wide range of guided tissue regeneration applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01AR055615. The authors would like to thank Artem B. Kutikov for assistance with SEM and Dr. Pingsheng Liu for assistance with contact angle measurements.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Carano RA, Filvaroff EH. Angiogenesis and bone repair. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:980–9. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02866-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Laschke MW, Harder Y, Amon M, Martin I, Farhadi J, Ring A, et al. Angiogenesis in tissue engineering: breathing life into constructed tissue substitutes. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2093–104. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Harris GM, Rutledge K, Cheng Q, Blanchette J, Jabbarzadeh E. Strategies to direct angiogenesis within scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:3456–65. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319190011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Novosel EC, Kleinhans C, Kluger PJ. Vascularization is the key challenge in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:300–11. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nguyen LH, Annabi N, Nikkhah M, Bae H, Binan L, Park S, et al. Vascularized bone tissue engineering: approaches for potential improvement. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:363–82. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ito H, Koefoed M, Tiyapatanaputi P, Gromov K, Goater JJ, Carmouche J, et al. Remodeling of cortical bone allografts mediated by adherent rAAV-RANKL and VEGF gene therapy. Nat Med. 2005;11:291–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Abaci A, Oguzhan A, Kahraman S, Eryol NK, Unal S, Arinc H, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on formation of coronary collateral vessels. Circulation. 1999;99:2239–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.17.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Waltenberger J. Impaired collateral vessel development in diabetes: potential cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:554–60. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kanczler JM, Oreffo RO. Osteogenesis and angiogenesis: the potential for engineering bone. Eur Cell Mater. 2008;15:100–14. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v015a08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell. 2011;146:873–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jain RK. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med. 2003;9:685–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Baiguera S, Ribatti D. Endothelialization approaches for viable engineered tissues. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cenni E, Perut F, Baldini N. In vitro models for the evaluation of angiogenic potential in bone engineering. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:21–30. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Said SS, Pickering JG, Mequanint K. Advances in growth factor delivery for therapeutic angiogenesis. J Vasc Res. 2013;50:35–51. doi: 10.1159/000345108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mehta M, Schmidt-Bleek K, Duda GN, Mooney DJ. Biomaterial delivery of morphogens to mimic the natural healing cascade in bone. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1257–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tayalia P, Mooney DJ. Controlled growth factor delivery for tissue engineering. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3269–85. doi: 10.1002/adma.200900241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Greenberg JI, Shields DJ, Barillas SG, Acevedo LM, Murphy E, Huang J, et al. A role for VEGF as a negative regulator of pericyte function and vessel maturation. Nature. 2008;456:809–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].English D, Welch Z, Kovala AT, Harvey K, Volpert OV, Brindley DN, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate released from platelets during clotting accounts for the potent endothelial cell chemotactic activity of blood serum and provides a novel link between hemostasis and angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2000;14:2255–65. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0134com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yatomi Y, Ohmori T, Rile G, Kazama F, Okamoto H, Sano T, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a major bioactive lysophospholipid that is released from platelets and interacts with endothelial cells. Blood. 2000;96:3431–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kimura T, Watanabe T, Sato K, Kon J, Tomura H, Tamama K, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates proliferation and migration of human endothelial cells possibly through the lipid receptors, Edg-1 and Edg-3. Biochem J. 2000;348(Pt 1):71–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lee MJ, Thangada S, Claffey KP, Ancellin N, Liu CH, Kluk M, et al. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. 1999;99:301–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shoham AB, Malkinson G, Krief S, Shwartz Y, Ely Y, Ferrara N, et al. S1P1 inhibits sprouting angiogenesis during vascular development. Development. 2012;139:3859–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.078550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gaengel K, Niaudet C, Hagikura K, Lavina B, Muhl L, Hofmann JJ, et al. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor S1PR1 restricts sprouting angiogenesis by regulating the interplay between VE-cadherin and VEGFR2. Dev Cell. 2012;23:587–99. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Takuwa Y, Du W, Qi X, Okamoto Y, Takuwa N, Yoshioka K. Roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in angiogenesis. World J Biol Chem. 2010;1:298–306. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i10.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Paik JH, Skoura A, Chae SS, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of N-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2392–403. doi: 10.1101/gad.1227804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, Mi Y, Deng CX, Hobson JP, et al. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:951–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Allende ML, Yamashita T, Proia RL. G-protein-coupled receptor S1P1 acts within endothelial cells to regulate vascular maturation. Blood. 2003;102:3665–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kawanabe T, Kawakami T, Yatomi Y, Shimada S, Soma Y. Sphingosine 1-phosphate accelerates wound healing in diabetic mice. J Dermatol Sci. 2007;48:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Qi X, Okamoto Y, Murakawa T, Wang F, Oyama O, Ohkawa R, et al. Sustained delivery of sphingosine-1-phosphate using poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based microparticles stimulates Akt/ERK-eNOS mediated angiogenesis and vascular maturation restoring blood flow in ischemic limbs of mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;634:121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sefcik LS, Petrie Aronin CE, Wieghaus KA, Botchwey EA. Sustained release of sphingosine 1-phosphate for therapeutic arteriogenesis and bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2869–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Petrie Aronin CE, Sefcik LS, Tholpady SS, Tholpady A, Sadik KW, Macdonald TL, et al. FTY720 promotes local microvascular network formation and regeneration of cranial bone defects. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1801–9. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Das A, Tanner S, Barker DA, Green D, Botchwey EA. Delivery of S1P receptor-targeted drugs via biodegradable polymer scaffolds enhances bone regeneration in a critical size cranial defect. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34779. doi/10.1002/jbm.a.34779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Petrie Aronin CE, Shin SJ, Naden KB, Rios PD, Jr., Sefcik LS, Zawodny SR, et al. The enhancement of bone allograft incorporation by the local delivery of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor targeted drug FTY720. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Huang C, Das A, Barker D, Tholpady S, Wang T, Cui Q, et al. Local delivery of FTY720 accelerates cranial allograft incorporation and bone formation. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:553–66. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1217-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wacker BK, Scott EA, Kaneda MM, Alford SK, Elbert DL. Delivery of sphingosine 1-phosphate from poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1335–43. doi: 10.1021/bm050948r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tengood JE, Kovach KM, Vescovi PE, Russell AJ, Little SR. Sequential delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor and sphingosine 1-phosphate for angiogenesis. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7805–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:753–63. doi: 10.1038/nri2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Aoki S, Yatomi Y, Ohta M, Osada M, Kazama F, Satoh K, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate-related metabolism in the blood vessel. J Biochem. 2005;138:47–55. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Murata N, Sato K, Kon J, Tomura H, Yanagita M, Kuwabara A, et al. Interaction of sphingosine 1-phosphate with plasma components, including lipoproteins, regulates the lipid receptor-mediated actions. Biochem J. 2000;352:809–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sachinidis A, Kettenhofen R, Seewald S, Gouni-Berthold I, Schmitz U, Seul C, et al. Evidence that lipoproteins are carriers of bioactive factors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2412–21. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.10.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Arkensteijn BW, Berbee JF, Rensen PC, Nielsen LB, Christoffersen C. The apolipoprotein m-sphingosine-1-phosphate axis: biological relevance in lipoprotein metabolism, lipid disorders and atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:4419–31. doi: 10.3390/ijms14034419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Christoffersen C, Obinata H, Kumaraswamy SB, Galvani S, Ahnstrom J, Sevvana M, et al. Endothelium-protective sphingosine-1-phosphate provided by HDL-associated apolipoprotein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9613–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103187108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hanson MA, Roth CB, Jo E, Griffith MT, Scott FL, Reinhart G, et al. Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2012;335:851–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1215904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wojciak JM, Zhu N, Schuerenberg KT, Moreno K, Shestowsky WS, Hiraiwa M, et al. The crystal structure of sphingosine-1-phosphate in complex with a Fab fragment reveals metal bridging of an antibody and its antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17717–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906153106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kutikov AB, Song J. An amphiphilic degradable polymer/hydroxyapatite composite with enhanced handling characteristics promotes osteogenic gene expression in bone marrow stromal cells. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:8354–64. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ercole F, Graichen FHM, Kyi S, O’Shea MS, Warden AC. WO 2009/127012 A1 Polyurethanes. 2009

- [48].Kishimoto Y, Radin NS. Occurrence of 2-Hydroxy Fatty Acids in Animal Tissues. J Lipid Res. 1963;4:139–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Foulon V, Sniekers M, Huysmans E, Asselberghs S, Mahieu V, Mannaerts GP, et al. Breakdown of 2-hydroxylated straight chain fatty acids via peroxisomal 2-hydroxyphytanoyl-CoA lyase: a revised pathway for the alpha-oxidation of straight chain fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9802–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Trimaille T, Gurny R, Moller M. Poly(hexyl-substituted lactides): novel injectable hydrophobic drug delivery systems. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80:55–65. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Trimaille T, Möller M, Gurny R. Synthesis and ring-opening polymerization of new monoalkyl-substituted lactides. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2004;42:4379–91. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lee OH, Kim YM, Lee YM, Moon EJ, Lee DJ, Kim JH, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces angiogenesis: its angiogenic action and signaling mechanism in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264:743–50. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kohno T, Igarashi Y. Attenuation of cell motility observed with high doses of sphingosine 1-phosphate or phosphorylated FTY720 involves RGS2 through its interactions with the receptor S1P. Genes Cells. 2008;13:747–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.