Abstract

We investigated the association between circulating levels of 60 and 70 kDa heat-shock proteins (HSP60 and 70) and cardiovascular risk factors in postmenopausal women with or without metabolic syndrome (MetS). This cross-sectional study included 311 Brazilian women (age ≥45 years with amenorrhea ≥12 months). Women showing three or more of the following diagnostic criteria were diagnosed with MetS: waist circumference (WC) ≥88 cm, blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) <50 mg/dl, and glucose ≥100 mg/dl. Clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical parameters were collected. HSP60, HSP70, antibodies to HSP60 and HSP70, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were measured in serum. Student's t test, Kruskal–Wallis test, chi-square test, and Pearson correlation were used for statistical analysis. Of the 311 women, 30.9 % (96/311) were diagnosed with MetS. These women were, on average, obese with abdominal fat deposition and had lower HDL values as well as higher triglycerides and glucose levels. Homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistant (HOMA-IR) test values in these women were compatible with insulin resistance (P < 0.05). CRP and HSP60 concentrations were higher in women with MetS than in women without MetS (P < 0.05). HSP60, anti-HSP70, and CRP concentrations increased with the number of features indicative of MetS (P < 0.05). There was a significant positive correlation between anti-HSP70 and WC, blood pressure and HOMA-IR, and between CRP and WC, blood pressure, glucose, HOMA-IR, and triglycerides (P < 0.05). In postmenopausal women, serum HSP60 and anti-HSP70 concentrations increased with accumulating features of the metabolic syndrome. These results suggest a greater immune activation that is associated with cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women with metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Cardiovascular risk, Menopause, Metabolic syndrome, Heat-shock proteins

Introduction

The risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), especially coronary heart disease (CHD), increases throughout life. CVD is the primary cause of death in women (Mosca et al. 2007). It is the end result of a multifactorial process of progressive development, which involves various factors such as hypercholesterolemia, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, stress, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity (Kannel et al. 2004). CHD is frequently fatal, but more than half of women with CHD do not present with early symptoms (Mosca et al. 2007). Hence, the evaluation of risk factors in asymptomatic women who are predisposed to CHD is crucial for its prevention.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a term that has been used to describe the clustering of several cardiometabolic disorders including abdominal obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia (Schneider et al. 2006). Owing to the increasing prevalence of the characteristic features of the MetS, in particular obesity, the syndrome is now regarded as a significant public health problem (Zhang et al. 2008a). Health statistics in the USA have shown a prevalence of 33 % among adults (Ford et al. 2004). We observed a similar 39.6 % prevalence of MetS in postmenopausal women residing in southeastern Brazil (Nahas et al. 2009).

Visceral adipose tissue plays an important role in the accumulation of metabolic disorders and chronic inflammation related to MetS (Dandona et al. 2005; Sowers et al. 2007). Epidemiologic studies have revealed that the prevalence of MetS reaches its highest level in women above 60 years of age (Ford et al. 2004; Janssen et al. 2008). The same trend has also been shown with regard to morbidity and mortality from CVD (Go et al. 2013). As the criteria for MetS are also important cardiovascular risk factors, their occurrence in MetS is associated with a dramatic elevation of CVD risk (Lin et al. 2010; Mente et al. 2010). Thus, the identification of risks factors for MetS in postmenopausal women will allow for earlier detection and intervention in this population.

Studies suggest the involvement of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) (Pockley et al. 2000; Xu et al. 2000; Shamaei-Tousi et al. 2007; Ellins et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2008b) and their antibodies (Prohászka et al. 2001; Kocsis et al. 2002; Herz et al. 2006) in the development of CVD. HSPs are molecular chaperones that under physiological conditions facilitate protein transport, folding, and assembly. The serum concentrations of two HSPs, the 60-kDa HSP (HSP60) and the 70-kDa HSP (HSP70), are greatly increased in response to nonphysiological conditions such as inflammation, infection, ischemia, and hyperthermia, and the presence of toxic metabolites (Calderwood et al. 2007; Lu and Kakkar 2010). Inside the cell, these two HSPs prevent protein denaturation, eliminate terminally misfolded proteins, and prevent the induction of cell death by apoptosis (Gupta and Knowlton 2002). Both HSP60 and HSP70 are also released from cells during stressful conditions and bind to surface receptors on immune and epithelial cells, triggering an immune-inflammatory response (Zanin-Zhorov et al. 2006). Furthermore, HSP60 and HSP70 can also be detected in the serum of apparently healthy individuals (Dulin et al. 2010).

Clinical studies regarding HSPs and CVD are controversial. HSP60 and anti-HSP60 antibodies have been shown to be increased in serum of CVD patients and correlated with the progression and severity of the disease (Pockley et al. 2000; Zhu et al. 2001; Xiao et al. 2005; Shamaei-Tousi et al. 2007; Ellins et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2008b). HSP60 is a potential molecular activator of the majority of cells involved in CHD, including vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells and T and B lymphocytes, and is associated with both the development and worsening of atherosclerosis (Xu et al. 2000; Srivastava 2002; Zanin-Zhorov et al. 2006). Conversely, HSP70 was shown to protect against the development of CHD (Zhu et al. 2003). This might involve a reduction in inflammation, oxidation, and apoptosis and an improvement in the viability of vascular smooth muscle cells (Bielecka-Dabrowa et al. 2009). In the study of Pockley et al. (2002), high levels of anti-HSP70 antibodies have been positively correlated with CHD. Conversely, a decrease in antiHSP70 antibodies in CVD has been also been described (Herz et al. 2006; Dulin et al. 2010).

Only three studies have evaluated an association between HSP60 and HSP70 and CVD risk in both male and female MetS patients (Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. 2005; Armutcu et al. 2008; Gruden et al. 2013). There have been a lack of studies focusing solely on postmenopausal women, which are a high-risk population for CHD and MetS. The presence of HSP60 and HSP70 in postmenopausal women with MetS and their correlation with CVD risk is still obscure. Based on these considerations, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the association between serum HSP60 and HSP70 concentration and metabolic factors of cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women with and without MetS.

Material and methods

Study population and design

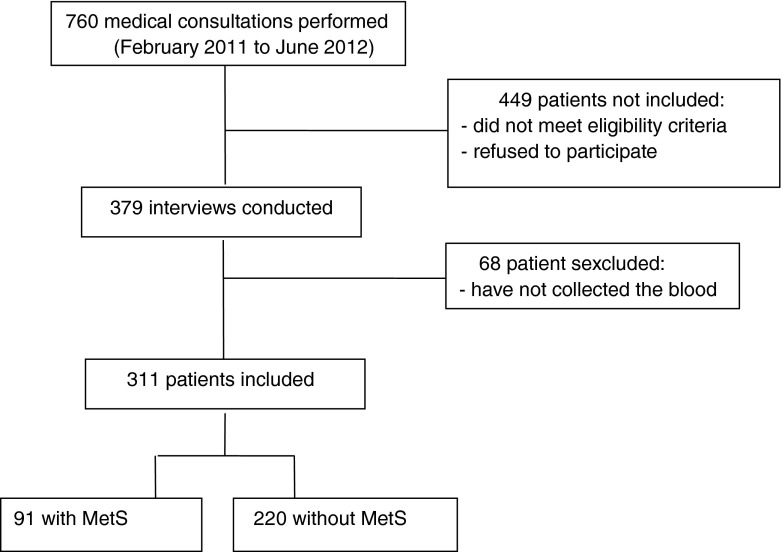

This is a clinical, analytical, cross-sectional, and comparative study. The study population was postmenopausal women, aged 45–70 years, attending a public outpatient center in a university hospital in Southeastern Brazil from February 2011 to June 2012. Sample size estimation was based on the study by Ellins et al. (2008) who detected elevated serum HSP60 values in 27.4 % of participants. Considering this frequency, with a 5 % level of significance and a 10 % type II error (90 % test power), the need to evaluate at least 303 participants was estimated. Women whose last menstruation was at least 12 months prior to study initiation and age ≥45 years old were included. The exclusion criteria were (1) known high cardiovascular risk due to existing or preexisting CHD, cerebrovascular arterial disease, abdominal aortic stenosis or aneurysm, peripheral artery disease, and chronic kidney disease and (2) history of hepatitis B and C, acute infection, lower genital tract infection, chronic inflammatory or autoimmune diseases (ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.), cancer, and addiction to either alcohol or illicit drugs. Figure 1 describes the 311 women that were included. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Botucatu Medical School, Sao Paulo State University/UNESP.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of women included in the study

Methodology

During the consultation, all subjects underwent individual interviews in which the following data were collected: age, time since menopause, current smoking, use of hormone therapy, personal history of hypertension, diabetes, and physical activity, as well as family history of CHD (acute myocardial infarction in 1st degree relative male aged <55 years and females aged <65 years). Blood pressure was measured using a standard aneroid sphygmomanometer on the right arm with patients in the sitting position, forearm resting at the level of the precordium, and the palm of the hand facing upwards, after a 5-min rest. Smokers were defined as persons who reported smoking regardless of the number of cigarettes smoked. Women who practiced aerobic physical exercise of moderate intensity for at least 30 min, five times a week (150/min/week) or resistance exercise three times a week were considered to be active. Women showing three or more of the following diagnostic criteria proposed by the US National Cholesterol Education Program/Adult Treatment Panel III (Adult Treatment Panel III 2001) were diagnosed as positive for MetS: waist circumference >88 cm, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol <50 mg/dl, blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg or under therapy, and fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dl or under therapy.

Assessment of cardiovascular risk

According to cardiovascular risk, study participants were allocated into three groups: high risk, intermediate risk, and low risk. Women with diabetes were considered to be at high cardiovascular risk. For women free of diabetes or known atherosclerotic disease, 10-year absolute risk of developing CHD was calculated based on the Framingham Risk Score (FRS), which includes age, total cholesterol, HDL, systolic blood pressure, and smoking status. Individual global scores were obtained by summing up the points for each risk factor. The points obtained were transcribed into a table including CHD relative risk and 10-year absolute risk (Wilson et al. 1998). Risk was classified as low (score ≤19; 10-year risk <10 %), intermediate (score of 20–22; 10-year risk of 10–20 %), or high (score ≥23; 10-year risk >20 %). Diabetes was defined as fasting blood glucose >126 mg/dl and/or use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents (American Diabetes Association 2006).

Anthropometry

The anthropometric data included weight, height, body mass index (BMI = weight/height2) and WC. Weight and height were determined with a standard balance beam scale (max. 150 kg, 0.1 kg accuracy) and portable wall anthropometer (0.1 cm accuracy), respectively, with patients wearing lightweight clothes and no shoes. BMI was classified according to the system used by the World Health Organization (2002): lower than 25 kg/m2 was defined as normal, from 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 as overweight, and above 30 kg/m2 as obesity. Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the lowest rib and the top of the iliac crest. The patients were advised to remain in the orthostatic position and the reading was performed at the moment of exhalation. This measurement was performed by a single evaluator (Nahas, EAP). Any WC exceeding 88 cm was considered elevated (Blümel et al. 2012).

Laboratory tests

Blood samples were collected from each subject, after 12 h of fasting. After centrifugation to remove the clot, samples underwent biochemical analysis immediately and a serum aliquot was frozen and kept at −80 °C for the HSP determinations. Triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), HDL, glucose, and C-reactive protein (CRP) measurements were processed by an automated analyzer, Model Vitros 950®, by the colorimetric dry chemistry method (Johnson & Johnson®, Rochester, NY, USA). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald formula in which total cholesterol is subtracted from the sum of HDL cholesterol and triglycerides, with the result being divided by five, which shows a usage limitation when TG values exceed 400 mg/dl. The values considered to be optimal were TC <200 mg/dl, HDL >50 mg/dl, LDL <100 mg/dl, TG <150 mg/dl, glucose <100 mg/dL, and CRP <1.0 mg/dl. Insulin was quantified using Immulite System® (DPC®, USA), which uses a solid-phase chemiluminescence immune assay, and assessed in the designated automatic analyzer for the quantitative reading. The normality rate ranged from 6.0 to 27.0 μIU/ml. To evaluate insulin resistance (IR), we used a method that was based on statistical measurement of two plasma components (insulin and fasting glucose). Homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistant (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the formula: insulin mU/ml × fasting glucose mg/dl / 405. IR was defined as HOMA-IR >2.7 (Geloneze et al. 2006).

Serum HSP60 and HSP70 and anti-HSP60 and anti-HSP70 antibodies

Serum concentrations of HSP60, HSP70, anti-HSP60 IgG, and anti-HSP70 IgG antibodies were assessed by ELISA immunoassays kits (Assay Designs®, Stressgen, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Analytical sensitivity was as follows: HSP60 = 3.13 ng/ml, HSP70 = 0.09 ng/ml, anti-HSP60 = 2.88 ng/ml, and anti-HSP70 = 6.79 ng/ml. Intra- and inter-assay variation coefficients were lower than 10 %. All evaluations were performed by the same researcher (Orsatti CL), to minimize inter-assay variations.

Statistical analysis

Variables were registered in tables according to the presence or absence of MetS. Quantitative data were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Values were expressed as means and standard deviation (SD) of the mean or, in the case of non-normally distributed data, as median and interquartile range. Data that were normally distributed were analyzed using the Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data found to be non-normally distributed were analyzed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test. The frequencies of categorical data were compared using the chi-square test. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bivariate correlations between the HSP and CRP concentration and possible cardiovascular risk factors and individual components of the MetS were performed using Pearson's rank correlation coefficients. Serum HSP60, HSP70, anti-HSP60, anti-HSP70, and CRP values were log transformed before using the Pearson correlation. The analyses were performed by using the Statistical Analyses System, version 9.2, by the Research Support Group (GAP) of the Botucatu Medical School, whose members provided methodological assistance and conducted the statistical procedures.

Results

In our study population, 30.9 % (96/311) of the women were positive for MetS. Table 1 shows the comparison between clinical and laboratorial characteristics of women with and without MetS. Both groups were similar in age, age and time since menopause, average values for cholesterol total, and LDL. As expected, patients with MetS were on average obese with abdominal fat deposition and presented with lower HDL values as well as higher triglycerides and glucose values when compared to the control group (P < 0.05). They also had HOMA-IR test values compatible with IR (>2.7). FRS percentage showed that both groups were classified as low risk for CHD; however, this was higher in women with MetS (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Women with MetS stated that they had lower exercise practice and higher incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in their family history when compared to the control group (7.7 vs. 22.3 % and 13.2 vs. 5.0 %, respectively; P < 0.05). FRS revealed a higher frequency of women classified as low risk in the control group (89.8 %) when compared to women with MetS (55.2 %) (P < 0.05). There were no differences in smoking status and the use of hormone replacement therapy (data not shown).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and laboratory characteristics of 311 postmenopausal women, with or without (control) metabolic syndrome (MetS)

| Characteristics | MetS (n = 96) | Control (n = 215) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55.4 (6.7) | 54.0 (6.7) | 0.060 |

| Age at menopause, years | 47.9 (4.5) | 47.4 (4.2) | 0.404 |

| Time of menopause, years | 6.0 (3.0–10.0) | 5.0 (2.0–10.0) | 0.133b |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.2 (4.4) | 27.7 (4.6) | <0.0001 |

| WC, cm | 105.0 (11.3) | 89.5 (10.5) | <0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 139.4 (16.4) | 124.3 (15.6) | <0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 85.6 (11.9) | 77.7 (10.1) | <0.0001 |

| FRS, % | 4.0 (2.0–11.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | <0.0001 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 107.3 (20.9) | 88.6 (10.8) | <0.0001 |

| Insulin, μIU/ml | 16.4 (12.3–21.5) | 6.8 (5.4–9.3) | <0.0001b |

| HOMA-IR | 4.3 (3.1–6.2) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) | <0.0001b |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 212.1 (37.4) | 198.2 (34.6) | 0.070 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 43.7 (7.8) | 56.8 (11.4) | <0.0001 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 124.5 (31.7) | 117.5 (33.6) | 0.102 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 209.5 (168.0–263.0) | 119.0 (92.5–152.5) | <0.0001b |

Date are presented as mean (SD) or median (IQ) range

MetS metabolic syndrome, BMI body mass index, WC waist circumference, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FRS Framingham risk score, HOMA-IR homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistant, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein

aSignificantly different between groups (P < 0.05; independent t test for normally distributed data)

bKruskal–Wallis test for non-normal distribution data

The comparison between immune-inflammatory markers in women with and without MetS is shown in Table 2. Median CRP and HSP60 concentrations were higher in women with MetS when compared to the control group (P < 0.05). There were no differences between groups in HSP70, anti-HSP60, and anti-HSP70 levels (Table 2). Serum HSP60, CRP, and anti-HSP70 concentrations steadily increased in women exhibiting more features of the MetS (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of serum C-reactive protein and heat-shock protein values in 311 postmenopausal women, with or without (control) metabolic syndrome (MetS)

| Variables | MetS (n = 96) | Control (n = 215) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP, mg/dl | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 0.5 (0.2–0.6) | <0.0001 |

| HSP60, ng/ml | 13.9 (6.3–18.0) | 11.2 (5.7–16.2) | 0.033 |

| Anti-HSP60, ng/ml | 48.0 (26.3–87.9) | 40.4 (24.6–80.7) | 0.916 |

| HSP70, ng/ml | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 0.903 |

| Anti-HSP70, ng/ml | 4.8 (2.3–7.2) | 4.6 (2.8–7.1) | 0.922 |

Date are presented as median (IQ) range

CRP C-reactive protein, HSP heat-shock protein

aSignificantly different between groups (P < 0.05; Kruskal–Wallis test)

Table 3.

Serum C-reactive protein and heat-shock protein values in 311 postmenopausal women with cumulative features of the metabolic syndrome (MetS)

| Features of MetS | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n) | 41 | 79 | 95 | 46 | 34 | 16 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.5 (0.3–0.6) | 0.5 (0.3–0.6) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.8a (0.5–1.4) | 1.1a (0.7–1.7) |

| HSP60, ng/ml | 10.6 (4.1–16.5) | 10.1 (4.4–16.0) | 11.6 (6.7–16.6) | 11.7 (6.7–15.6) | 13.7a (8.7–18.0) | 14.6a (8.1–17.7) |

| Anti-HSP60, ng/ml | 45.5 (26.3–66.0) | 43.5 (24.2–68.2) | 51.2 (30.8–83.7) | 49.1 (29.5–91.3) | 41.4 (22.8–94.7) | 47.0 (18.3–80.8) |

| HSP70, ng/ml | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) |

| Anti-HSP70, ng/ml | 4.6 (1.8–7.3) | 4.3 (2.2–6.7) | 4.6 (2.8–7.0) | 4.9 (2.4–7.1) | 5.5 (3.4–7.1) | 6.2a (2.6–8.4) |

Date are presented as median (IQ) range

CRP C-reactive protein, HSP heat-shock protein

a P < 0.05; ANOVA

Correlations between serum CRP and HSP values with metabolic cardiovascular risk factors in postmenopausal women with or without MetS are shown in Table 4. There was a positive correlation between HSP70 levels and age and time since menopause only in the control group. There was a positive correlation between anti-HSP70 levels and WC, arterial systolic and diastolic pressures, and HOMA-IR only in the MetS group. CRP levels were correlated with age, BMI, WC, arterial systolic and diastolic pressures, glucose, and HOMA-IR in the MetS group and with age, time since menopause, BMI, WC, arterial systolic pressure, glucose, and HOMA-IR in the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 4). There was no correlation with CRP, HSP70, and anti-HSP70 with other risk factors such as age at menopause, FRS%, and HDL (P > 0.05). Also, there were no correlations between HSP60 and anti-HSP60 and all the metabolic risk factors assessed.

Table 4.

Correlations (r) between serum C-reactive protein and heat-shock protein (HSP) values with metabolic cardiovascular risk factors in 311 postmenopausal women, with (n = 96) or without (control, n = 215) metabolic syndrome (MetS)

| Risk factors | HSP60 | Anti-HSP60 | HSP70 | Anti-HSP70 | CRP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetS | Control | MetS | Control | MetS | Control | MetS | Control | MetS | Control | |

| Age, years | –0.14 (0.18) | 0.02 (0.77) | –0.04 (0.69) | –0.07 (0.33) | 0.10 (0.32) | 0.33 (<0.0001) | 0.11 (0.29) | 0.06 (0.35) | 0.17 (0.04) | 0.20 (0.003) |

| Time of menopause, years | –0.18 (0.09) | 0.06 (0.41) | 0.02 (0.82) | –0.01 (0.91) | 0.02 (0.86) | 0.29 (<0.0001) | 0.09 (0.41) | 0.07 (0.29) | 0.14 (0.17) | 0.19 (0.004) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | –0.15 (0.15) | 0.04 (0.55) | 0.06 (0.53) | 0.09 (0.18) | 0.10 (0.32) | –0.05 (0.49) | 0.12 (0.28) | 0.02 (0.97) | 0.28 (0.008) | 0.26 (<0.001) |

| WC, cm | –0.18 (0.09) | 0.09 (0.18) | –0.11 (0.29) | 0.02 (0.74) | 0.09 (0.41) | –0.11 (0.10) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.09) | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.27 (<0.0001) |

| SBP, mmHg | 0.001 (0.99) | –0.03 (0.63) | –0.06 (0.54) | 0.10 (0.14) | –0.03 (0.72) | 0.06 (0.42) | 0.26 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.24 (0.004) |

| DBP, mmHg | 0.14 (0.19) | 0.03 (0.57) | 0.07 (0.47) | 0.08 (0.23) | 0.02 (0.87) | 0.01 (0.96) | 0.31 (0.003) | 0.13 (0.08) | 0.30 (0.003) | 0.13 (0.06) |

| Glucose, mg/dl | –0.07 (0.51) | 0.01 (0.89) | 0.009 (0.99) | –0.06 (0.39) | –0.09 (0.39) | 0.05 (0.46) | 0.10 (0.37) | 0.04 (0.60) | 0.38 (0.0002) | 0.32 (<0.0001) |

| HOMA-IR | –0.09 (0.42) | 0.06 (0.42) | 0.11 (0.31) | –0.07 (0.33) | –0.09 (0.37) | –0.01 (0.98) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.18 (0.08) | 0.42 (<0.0001) | 0.30 (<0.0001) |

| LDL, mg/dl | 0.05 (0.63) | 0.08 (0.19) | 0.15 (0.14) | –0.03 (0.70) | –0.11 (0.28) | 0.17 (0.12) | 0.05 (0.65) | 0.01 (0.80) | 0.04 (0.68) | 0.05 (0.44) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 0.17 (0.16) | 0.04 (0.53) | 0.13 (0.23) | –0.03 (0.66) | 0.03 (0.76) | 0.14 (0.23) | 0.09 (0.37) | 0.04 (0.50) | 0.14 (0.17) | 0.06 (0.38) |

Data are presented as r value and P value in parentheses. Data presented in Bold are significant

MetS metabolic syndrome, BMI body mass index, WC waist circumference, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FRS Framingham risk score, HOMA-IR homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistant, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein

a P < 0.05; Pearson correlation

Discussion

While the presence of MetS is associated with an increased risk of CHD, there is only limited evidence that the risk is greater than that conferred by each MetS component individually (Lin et al. 2010; Mente et al. 2010). In the current study, serum HSP60, anti-HSP70, and CRP concentrations increased in association with the number of MetS-associated factors present in individual women. These results suggest a greater immune activation, which is associated with cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women with MetS. Our data indicate that anti-HSP70 antibody and CRP are associated with the classical cardiovascular risk factors.

In this study, a MetS occurrence of 30.9 % was identified in postmenopausal women seen at a public healthcare center. Although this finding may not extrapolate to the general population, it is in line with other studies. MetS prevalence in postmenopausal women has been reported to reach 35.1 % in Latin America women (not including Brazil) (Royer et al. 2007), 33 % in the USA (Ford et al. 2004), and 27.3 % in China (Ding et al. 2007). The prevalence of obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes has increased among Brazilian women of different socioeconomic and cultural status (Piegas et al. 2003). Thus, regardless of their ethnic origin, the prevalence of MetS is high in postmenopausal women (Janssen et al. 2008; Nahas et al. 2009; Blümel et al. 2012).

Despite the high incidence of MetS in our participants, the Framingham score risk assessment revealed a population at low absolute risk (<10 %) for development of coronary events in 10 years. This result is in agreement with other studies that specifically evaluated postmenopausal women and demonstrated them to be a population of low cardiovascular risk when assessed in isolation by FRS (Pelletier et al. 2009; Agrinier et al. 2010; Nahas et al. 2013). It is recognized that menopause significantly changes the profile of cardiovascular risk (Pappa and Alevizaki 2012). Hence, we have to be alert, as previously stated (Lakoski et al. 2007; Lambrinoudaki et al. 2013), to the risk scores that are exclusively based on traditional risk factors, since they underestimate cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women.

The dominant underlying risk factors for MetS appear to be abdominal obesity and insulin resistance (Dandona et al. 2005). The biological mechanisms between IR and metabolic risk factors, at the molecular level, are not fully understood and appear to be complex. Most people with insulin resistance have abdominal obesity (Zhang et al. 2008a). Obesity can be considered as a low-grade inflammatory condition (Gregor and Hotamisligil 2011). Inflammation related to obesity may also be connected to the increased risk of CHD among obese persons (Musaad and Haynes 2007; Wildman et al. 2011). Increased fat cell mass (i.e., obesity) is associated with higher levels of CRP in postmenopausal women (Piché et al. 2005; Barinas-Mitchell et al. 2001). It has been suggested that the increase in abdominal adipose tissue deposition observed at menopause represents an important source of cytokine production, which would in turn stimulate hepatic CRP production (Piché et al. 2005). The present study found a strong relationship between CRP, adiposity index, and IR in patients with MetS. This result is compatible with a mechanism whereby inflammation induces IR (Gregor and Hotamisligil 2011), thus leading to clinical and biochemical manifestations of MetS (Lann and LeRoith 2007).

In line with previous studies (Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. 2005; Nahas et al. 2009; Wildman et al. 2011; Belfki et al. 2012), we found that CRP concentrations rose with an increase in the number of features of MetS. These other investigators have also reported a positive correlation between CRP and fasting glucose, HOMA-IR, triglycerides, and blood pressure and a negative correlation with HDL cholesterol. CRP is an inflammatory biomarker whose levels are higher in postmenopausal women (Ridker et al. 2000; Wildman et al. 2011). CRP concentration is associated with traditional CVD risk factors and is being considered as an emerging CVD risk factor (Young et al. 2013). It is also a predictive factor for AMI, stroke, and sudden death (Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. 2007). Hence, a simple CRP concentration measurement should be performed during an evaluation of cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women with MetS.

Several common characteristics of CVD risk and MetS such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia have been associated with increased levels of some HSPs (Pockley et al. 2002; Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. 2005, 2007; Shamaei-Tousi et al. 2007). In the current study, serum HSP60 and anti-HSP70 concentrations rose with accumulating features of the MetS, although this was not the case for HSP70 and anti-HSP60. The underlying cellular mechanisms of anti-HSP70 antibody rise in patients with accumulating features of MetS remain elusive. However, it is likely to reflect a relatively greater exposure to extracellular HSP70, possibly triggered by MetS-associated oxidative stress (Armutcu et al. 2008, Gruden et al. 2013), which is a known inducer of extracellular HSP70 release (Zhang et al. 2010). This is in agreement with Chung et al. (2008) who observed in obese patients with type 2 diabetes reduced HSP70 expression in insulin-sensitive tissues and linked this downregulation to the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. It has been suggested that HSP70 is an integral component of a cycle that, when induced, results in the development of DM (Hooper and Hooper, 2009). The cycle operates as follows: (a) induction of inflammation promotes development of insulin resistance; (b) impaired insulin signaling leads to a reduced ability to express HSP70; (c) this results in decreased ability of HSP70 to protect cells and enhance survival under nonphysiological conditions; and (d) the resulting cell damage leads to increased tissue damage, including to pancreatic islet cells, and a further induction of pro-inflammatory immunity (Hooper and Hooper, 2009).

However, data regarding the levels of HSP60 and HSP70 or their corresponding antibodies in patients with MetS are scarce. Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. (2005) evaluated 237 patients with dyslipidemia and other features of MetS (60 % males, 55.2 ± 0.9 years) and 135 healthy controls participants (50 % males, 48.9 ± 1.3 years). Compared to the controls, the patients had higher anti-HSP60 and anti-HSP70 levels and elevated CRP concentrations. In a clinical case–control study, Armutcu et al. (2008) observed a decrease in HSP70 levels, which was associated with an increase in CRP in 36 MetS patients of both genders when compared to 33 healthy control participants. Gruden et al. (2013), in a cross-sectional case–control study, evaluated 180 patients (61 % males, 60.9 ± 8.6 years) with MetS without CVD as well as 136 controls (53.5 % males, 54.6 ± 6.5 years). They found that anti-HSP70 antibody levels were significantly higher in MetS patients than in control, regardless of age or gender. Excess body weight was likely a major determinant of this rise in anti-HSP70 antibody levels (Gruden et al. 2013). However, there are no reported data concerning circulating HSP60 and HSP70 or their corresponding antibody levels in postmenopausal women with MetS.

In the current study, significantly higher serum HSP60 concentrations were found in subjects with MetS, and anti-HSP70 levels were found to be positively correlated with WC, blood pressure, and HOMA-IR, which are risk factors for CVD and MetS. Our study is in agreement with previous studies that have shown an association between circulating anti-HSP70 antibody levels and single parameters of the MetS, such as hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia (Pockley et al. 2002; Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. 2007). Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. (2007) have investigated the association between obesity indices and HSP antibody titers in 170 healthy participants. Obese patients had significantly higher plasma anti-HSP60, anti-HSP65, and anti-HSP70 concentrations when compared to overweight and normal weight subjects. The high antibody titers to HSP60, HSP65, and HSP70 in obese subjects without established coronary disease may be related to a heightened state of immunoactivation associated with obesity (Ghayour-Mobarhan et al. 2007). On the other hand, Dulin et al. (2010) reported decreases in serum HSP70 and anti-HSP70 levels in patients with established CVD. This could be explained by circulating immune complex formation and both could be proposed as a biomarker for the progression of atherosclerotic disease (Dulin et al. 2010). Similar results were shown by Zhang et al. (2010) in patients with CHD. These discrepant results might be related to both different patient profiles and different inclusion criteria. In the present study, we have purposely selected patients with MetS, without known CVD. However, the clinical significance of such increased anti-HSP levels is yet to be clarified.

Our results collaborate earlier studies (Snoeckx et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2008b) in which there was no correlation between CRP and both HSP60 and HSP70 levels. These data suggest that CRP and HSPs might influence or reflect the risk of CVD through different mechanisms. A control case study of 1,003 patients (40–79 years old) with established CHD and 1,003 healthy controls showed that the average value for HSP60 was higher in CHD patients. However, there was no significant association between HSP60 with CHD risk factors such as gender, smoking, weight, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and CRP values (Zhang et al. 2008b). Another study of 456 Spanish patients (218 men and 234 women, 40–60 years old) also did not show a correlation between plasma concentrations of HSP70, anti-HSP70, and anti-HSP60 and classical cardiovascular risk factors or CRP values (Dulin et al. 2010).

It is generally accepted that expression of HSPs is an early and sensitive biomarker of cell stress. These proteins have a critical role in maintaining cells in a normal homeostatic state and facilitating their recovery from adverse stress (Snoeckx et al. 2001). HSP60 and HSP70 expressions have been evaluated in relation to many clinical conditions, including hypertension and atherosclerosis (Pockley et al. 2002; Ellins et al. 2008). However, the mechanism related to a change in HSP60 and HSP70 concentrations and levels of their antibodies in MetS had not previously been determined in postmenopausal women. In the present study, we observed a strong association between individual coronary risk factors and accumulating features of MetS with HSP60 and anti-HSP70 concentrations in postmenopausal women with MetS. Further studies are required to determine causal relationships and elucidate underlying mechanisms for this association.

There are certain limitations to a cross-sectional study. It restricts our ability to assess temporal relationships between HSPs and their antibody levels and MetS and to identify causal biological mechanisms underlying this association. Secondly, the presence of CHD was assessed based on clinical data, and therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that some CHD patients might have been erroneously included. On the other hand, there is no previous data on HSP60 and HSP70 and their antibodies and MetS in postmenopausal women. Therefore, this study might be used as a reasonable starting point to approach this issue.

In conclusion, in postmenopausal women, serum HSP60 and anti-HSP70 concentrations increased with accumulating features of the MetS. There was a correlation between serum anti-HSP70 values and metabolic factors of cardiovascular risk. These results suggest a greater immune activation that is associated with cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women with metabolic syndrome.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), process number 2009/14884-2. The authors have no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in the products or instruments described in this article.

References

- Adult Treatment Panel III Executive Summary of The Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrinier N, Cournot M, Dallongeville J, Arveiler D, Ducimetière P, Ruidavets JB, Ferrières J. Menopause and modifiable coronary heart disease risk factors: a population based study. Maturitas. 2010;65(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of medical care in diabetes—2006. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(suppl 1):S4–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armutcu F, Ataymen M, Atmaca H, Gurel A. Oxidative stress markers, C-reactive protein and heat shock protein 70 levels in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Clin Chem LabMed. 2008;46(6):785–790. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barinas-Mitchell E, Cushman M, Meilahn EN, Tracy RP, Kuller LH. Serum levels of C-reactive protein are associated with obesity, weight gain and hormone replacement therapy in healthy postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(11):1094–1101. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.11.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfki H, Ben Ali S, Bougatef S, Ben Ahmed D, Haddad N, Jmal A, Abdennebi M, Ben Romdhane H. Relationship of C-reactive protein with components of the metabolic syndrome in a Tunisian population. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(1):e5–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielecka-Dabrowa A, Barylski M, Mikhailidis DP, Rysz J, Banch M. HSP 70 and atherosclerosis-protector or activator? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13(3):307–317. doi: 10.1517/14728220902725149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blümel JE, Legorreta D, Chedraui P, Ayala F, Bencosme A, Danckers L, Lange D, Espinoza MT, Gomez G, Grandia E, Izaguirre H, Manriquez V, Martino M, Navarro D, Ojeda E, Onatra W, Pozzo E, Prada M, Royer M, Saavedra JM, Sayegh F, Tserotas K, Vallejo MS, Zuñiga C, Collaborative Group for Research of the Climacteric in Latin America (REDLINC) Optimal waist circumference cutoff value for defining the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal Latin American women. Menopause. 2012;19(4):433–437. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318231fc79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood SK, Mambula SS, Gray PJ., Jr Extracellular heat shock proteins in cell signaling and immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113(1):28–39. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Nguyen AK, Henstridge DC, Holmes AG, Chan MH, Mesa JL, Lancaster GI, Southgate RJ, Bruce CR, Duffy SJ, Horvath I, Mestril R, Watt MJ, Hooper PL, Kingwell BA, Vigh L, Hevener A, Febbraio MA. HSP72 protects against obesity-induced insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1739–1744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705799105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P, Garg R. Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation. 2005;111(11):1448–1454. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158483.13093.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding OF, Hayashi T, Zhang XJ, Funami J, Ge L, Li J, Huang XL, Cao L, Zhang J, Akihisa I. Risks of CHD identified by different criteria of metabolic syndrome and related changes of adipocytokines in elderly postmenopausal women. J Diabetes Compl. 2007;21(5):315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin E, García-Barreno P, Guisasola MC. Extracellular heat shock protein 70 (HSPA1A) and classical vascular risk factors in general population. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15(6):929–937. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0201-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellins E, Shamaei-Tousi A, Steptoe A, Donald A, O'Meagher S, Halcox J, Henderson B. The relationship between carotid stiffness and circulating levels of heat shock protein 60 in middle-aged men and women. J Hypertens. 2008;26(12):2389–2392. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328313918b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokad AH. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2444–2449. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geloneze B, Repetto EM, Geloneze SR, Tambascia MA, Ermetice MN. The threshold value for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in an admixture population IR in the Brazilian Metabolic Syndrome Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;72(2):219–220. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Lamb DJ, Lovell DP, Livingstone C, Wang T, Ferns GAA. Plasma antibody titres to heat shock proteins-60, -65 and-70: their relationship to coronary risk factors in dyslipidaemic patients and healthy individuals. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2005;65(7):601–613. doi: 10.1080/00365510500333858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Taylor A, Lamb DJ, Ferns GA. Association between indices of body mass and antibody titres to heat-shock protein-60, -65 and -70 in healthy Caucasians. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(1):197–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(1):e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29(1):415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruden G, Barutta F, Pinach S, Lorenzati B, Cavallo-Perin P, Giunti S, Bruno G. Circulating anti-Hsp70 levels in nascent metabolic syndrome: the Casale Monferrato Study. Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2013;18(3):353–357. doi: 10.1007/s12192-012-0388-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Knowlton AA. Cytosolic heat shock protein 60, hypoxia, and apoptosis. Circulation. 2002;106(21):2727–2733. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000038112.64503.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz I, Rosso R, Roth A, Keren G, George J. Serum levels of anti heat shock protein 70 antibodies in patients with stable and unstable angina pectoris. Acute Card Care. 2006;8(1):46–50. doi: 10.1080/14628840600606950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper PL, Hooper PL. Inflammation, heat shock proteins, and type II diabetes. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14(2):113–115. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0073-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Powell LH, Crawford S, Lasley B, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Menopause and the metabolic syndrome: the study of women's health across the nation. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1568–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Wilson PWF. Concept and usefulness of cardiovascular risk profiles. Am Heart J. 2004;148(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis J, Veres A, Vatay A, Duba J, Karádi I, Füst G, Prohászka Z. Antibodies against the human heat shock protein hsp70 in patients with severe coronary artery disease. Immunol Invest. 2002;31(3–4):219–231. doi: 10.1081/IMM-120016242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakoski SG, Greenland P, Wong ND, Schreiner PJ, Herrington DM, Kronmal RA, Liu K, Blumenthal RS. Coronary artery calcium scores and risk for cardiovascular events in women classified as “low risk” based on Framingham Risk Score: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2437–2442. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrinoudaki I, Armeni E, Georgiopoulos G, Kazani M, Kouskouni E, Creatsa M, Alexandrou A, Fotiou S, Papamichael C, Stamatelopoulos K. Subclinical atherosclerosis in menopausal women with low to medium calculated cardiovascular risk. Int J Cardiol. 2013;164(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lann D, LeRoith D. Insulin resistance as the underlying cause for the metabolic syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91(6):1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JW, Caffrey JL, Chang MH, Lin YS. Sex, menopause, metabolic syndrome, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality-cohort analysis from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2010;95(9):4258–4267. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Kakkar V. The role of heat shock protein (HSP) in atherosclerosis: patho-physiology and clinical opportunists. Curr Med Chemistry. 2010;17(10):957–973. doi: 10.2174/092986710790820688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mente A, Yusuf S, Islam S, McQueen MJ, Tanomsup S, Onen CL, Rangarajan S, Gerstein HC, Anand SS, INTERHEART Investigators Metabolic syndrome and risk of acute myocardial infarction a case–control study of 26,903 subjects from 52 countries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(21):2390–2398. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bushnell C, Dolor RJ, Ganiats TG, Gomes AS, Gornik HL, Gracia C, Gulati M, Haan CK, Judelson DR, Keenan N, Kelepouris E, Michos ED, Newby LK, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Oz MC, Petitti D, Pinn VW, Redberg RF, Scott R, Sherif K, Smith SC, Jr, Sopko G, Steinhorn RH, Stone NJ, Taubert KA, Todd BA, Urbina E, Wenger NK, Expert Panel/Writing Group Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115(11):1481–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musaad S, Haynes EN. Biomarkers of obesity and subsequent cardiovascular events. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29(10):98–114. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahas EAP, Padoani NP, Nahas-Neto J, Orsatti FL, Tardivo AP, Dias R. Metabolic syndrome and its associated risk factors in Brazilian postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2009;12(5):431–438. doi: 10.1080/13697130902718168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahas EA, Andrade AM, Jorge MC, Orsatti CL, Dias FB, Nahas-Neto J. Different tools for estimating cardiovascular risk in Brazilian postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(10):921–925. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2013.819084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa T, Alevizaki M. Endogenous sex steroids and cardio- and cerebro-vascular disease in the postmenopausal period. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(2):145–156. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier P, Lapointe A, Laflamme N, Piche ME, Weisnagel SJ, Nadeau A, Lemieux S, Bergeron J. Discordances among different tools used to estimate cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(12):e413–e416. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70535-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piché ME, Lemieux S, Weisnagel SJ, Corneau L, Nadeau A, Bergeron J. Relation of high sensitivity C-protein, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and fibrinogen abdominal adipose tissue, blood pressure, and cholesterol and triglyceride levels in healthy postmenopausal women. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(1):92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piegas LS, Avezum A, Pereira JC, Neto JM, Hoepfner C, Farran JA, Ramos RF, Timerman A, Esteves JP, AFIRMAR Study Investigators Risk factors for myocardial infarction in Brazil. Am Heart J. 2003;146(2):331–338. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Wu R, Lemne C, Kiessling R, de Faire U, Frostegard J. Circulating HSP 60 is associated with early cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2000;36(2):303–373. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.36.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, de Faire U, Kiessling R, Lemne C, Thulin T, Frostegård J. Circulating heat shock protein and heat shock protein antibody levels in established hypertension. J Hypertens. 2002;20(9):1815–1820. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200209000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohászka Z, Duba J, Horváth L, Császár A, Karádi I, Szebeni A, Singh M, Fekete B, Romics L, Füst G. Comparative study on antibodies to human and bacterial 60 kDa heat shock proteins in a large cohort of patients with coronary heart disease and healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31(4):285–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Hennekenes CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other marker of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(12):836–843. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer M, Castelo-Branco C, Blümel JE, Chedraui PA, Danckers L, Bencosme A, Collaborative Group for Research of the Climacteric in Latin America The US national cholesterol education programme adult treatment panel III (NCEP ATP III): prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal Latin American women. Climacteric. 2007;10:164–170. doi: 10.1080/13697130701258895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JG, Tompkins C, Blumenthal RS, Mora S. The metabolic syndrome in women. Cardiol Res. 2006;14(6):286–291. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000233757.15181.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamaei-Tousi A, Halcox JP, Henderson B. Stressing the obvious? Cell stress and cell stress proteins in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74(10):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoeckx LH, Cornelussen RN, Van Nieuwenhoven FA, Reneman RS, Van Der Vusse GJ. Heat shock proteins and cardiovascular pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(4):1461–1497. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers MF, Zheng H, Tomey K, Karvonen-Gutierrez C, Jannausch M, Li X, Yosef M, Symons J. Changes in body composition in women over six years at midlife: ovarian and chronological aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):895–901. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P. Roles of heat-shock proteins in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(3):185–194. doi: 10.1038/nri749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2002) Diet, Nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. In: World Heath Organization. Geneva: WHO/FAO (Reports of WHO/FAO. Expert Consultation on diet, nutrition and prevention of chronic diseases)

- Wildman RP, Kaplan R, Manson JE, Rajkovic A, Connelly SA, Mackey RH, Tinker LF, Curb JD, Eaton CB, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Body size phenotypes and inflammation in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(7):1482–1491. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q, Mandal K, Schett G, Mayr M, Wick G, Oberhollenzer F, Willeit J, Kiechl S, Xu Q. Association of serum-soluble heat shock protein 60 with carotid atherosclerosis: clinical significance determined in a follow-up study. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2571–2576. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189632.98944.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Schett G, Perschinka H, Mayr M, Egger G, Oberhollenzer F, Willeit J, Kiechl S, Wick G. Serum soluble heat shock protein 60 is elevated in subjects with atherosclerosis in a general population. Circulation. 2000;102(1):14–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D, Camhi S, Wu T, Hagberg J, Stefanick M. Relationships among changes in C-reactive protein and cardiovascular disease risk factors with lifestyle interventions. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(9):857–863. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanin-Zhorov A, Cahalon L, Tal G, Margalit R, Lider O, Cohen IR. Heat shock protein 60 enhances CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell function via innate TLR signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):2022–2032. doi: 10.1172/JCI28423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhang C, Rexrode KM, vanDam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardio-vascular, and cancer mortality, 16 years of follow-up in US women. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1658–1667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, He M, Cheng L, Chen Y, Zhou L, Zeng H, Pockley AG, Hu FB, Wu T. Elevated heat shock protein 60 levels are associated with higher risk coronary disease in Chinese. Circulation. 2008b;118(25):2687–2693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.781856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Xu Z, Zhou L, Chen Y, He M, Cheng L, Hu FB, Tanguay RM, Wu T. Plasma levels of Hsp70 and anti-Hsp70 antibody predict risk to acute coronary syndrome. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15(5):675–686. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0180-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Quyyumi AA, Rott D, Csako G, Wu H, Halcox J, Epstein SE. Antibodies to human heat-shock protein 60 are associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease: evidence for an autoimmune component of atherogenesis. Circulation. 2001;103(8):1071–1075. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.8.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Quyyumi AA, Wu H, Csako G, Rott D, Zalles-Ganley A, Ogunmakinwa J, Halcox J, Epstein SE. Increased serum levels of heat shock protein 70 are associated with low risk of coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(6):1055–1059. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000074899.60898.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]