Abstract

Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) was shown recently to be promising for improving upper-limb function in children with cerebral palsy (CP). This study investigated the changes in cerebral perfusion with single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) after modified CIMT (child-friendly CIMT) in young hemiplegic girls. Two young children with left hemiplegic CP were studied with SPECT at rest before and after the CIMT period, and they also performed standardized upper motor function tests [Jebsen hand function test, quality of upper extremity skills test (QUEST), and dynamic electromyography (EMG)]. The cerebral perfusion SPECT revealed regional perfusion increase in the motor cortex area in the affected hemisphere, and the changes associated with functional gain. Our cases showed that intensive movement therapy appears to change local cerebral perfusion and SPECT could show these changes in children with hemiplegic CP.

Keywords: CIMT, Hemiplegic cerebral palsy, SPECT

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) describes a group of disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation that is attributed to persistent but non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain [1]. Spastic hemiplegia is a common form of CP which lead to disability with one side involvement and results from involvement of the motor cortex or white matter projections to and from the cortical sensorimotor areas of the brain.

Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is a physical rehabilitation method that has been used in chronic stroke patients based on Taub’s study [2] and was shown recently to be promising for improving upper-limb function in children with CP [3–5].

Brain reorganization was observed in patients with various types of peripheral lesion or injury of central nervous system. Many studies of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) for the evaluation of cortical reorganization in adult stroke patients have been published [6]. Positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) were also used to evaluate changes in cerebral metabolism and blood flow in adult stroke patients. However, few imaging studies have been conducted in children with CP after CIMT [7–9]. We report changes of cerebral blood flow in children with CP using brain SPECT after CIMT and confirmed the recovery of motor function.

Case Report

Two girls aged 6 and 7 years with left hemiplegic CP (patient 1 and 2, each) received CIMT over a 4-week period using a before and after design. Their parents gave informed consent and assent to the study.

The children were treated with a 4-week protocol of modified CIMT, which consisted of twice-weekly, 1-hour sessions of conventional rehabilitative therapy and the children wore a brace on their non-involved upper extremity for 6 h per day. Children were measured with SPECT before and after of the CIMT (within 1 wk). MRI was not done around the same time.

For the SPECT, a total of 7.4 MBq/kg of Tc-99 m ethylcysteine dimer (Neurolite, Dupont Pharma/Durham APS, Kastrup, Denmark) was intravenously injected into the patient in a quiet room. The SPECT images were obtained 10–20 min later with a three-head SPECT (MultiSPECT 3; Siemens Medical System, USA). Transaxial slices were reconstructed using a Butterworth filter, and a Chang attenuation correction was applied [10]. After the realignment of both SPECT images, each image was spatially normalized with the SPM2 (statistical parametric mapping; Institute of Neurology, University of London, UK) and Matlab 6.5 (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). SISCOM (subtraction ictal single photon emission computed tomography coregistered to magnetic resonance imaging) has been used to determine the differences of two images (before and after the CIMT). Perfusion changes of >10 % were regarded as significant, and the perfusion change map containing significant pixels was superimposed on a MRI template.

Jebsen hand function test and QUEST (Quality of upper extremity skills test) were performed to evaluate upper-extremity function before and after the CIMT [11]. Semmes-Weinstein monofilament and two-point discrimination were performed to evaluate sensory function. Dynamic EMG were also performed. All tests were performed within several days after CIMT.

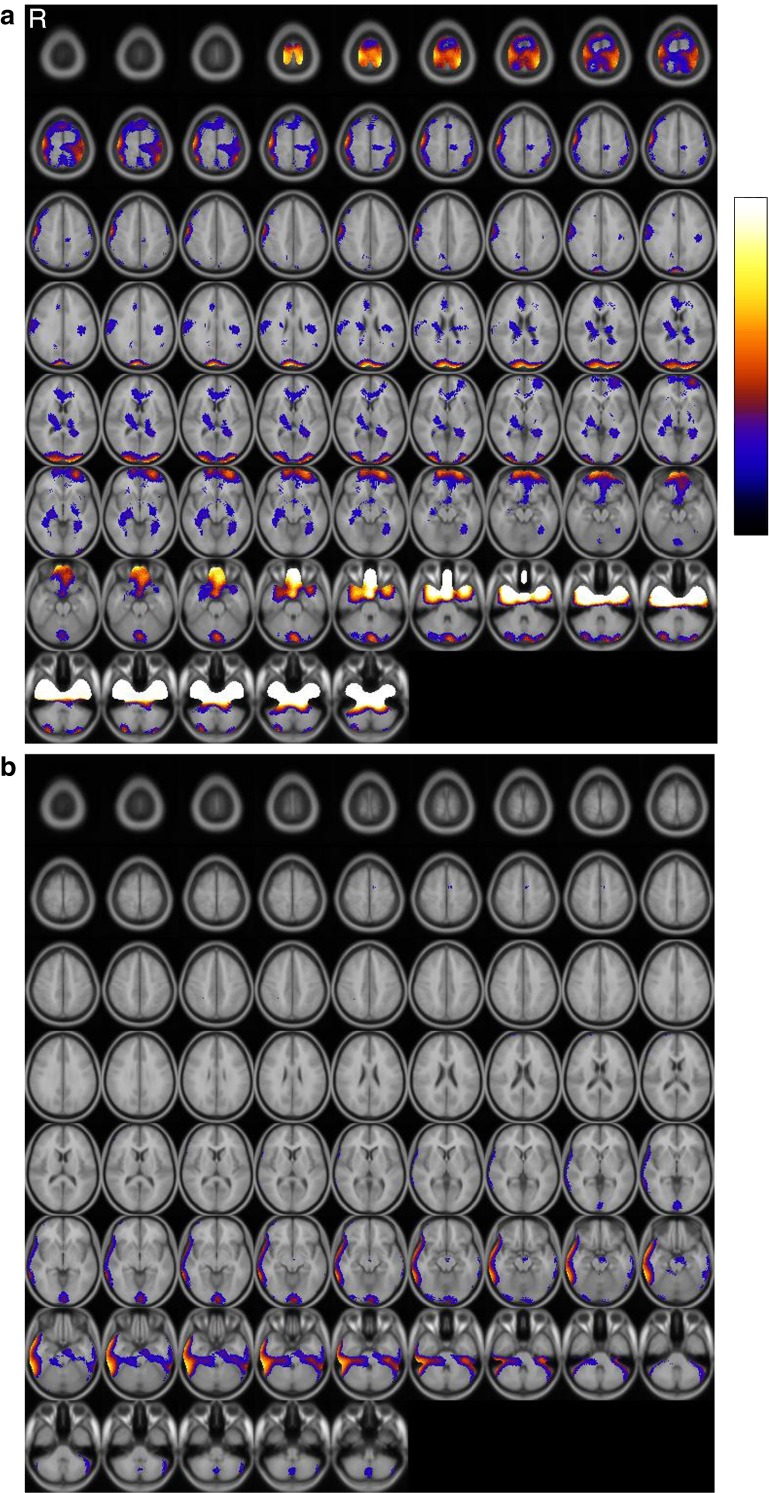

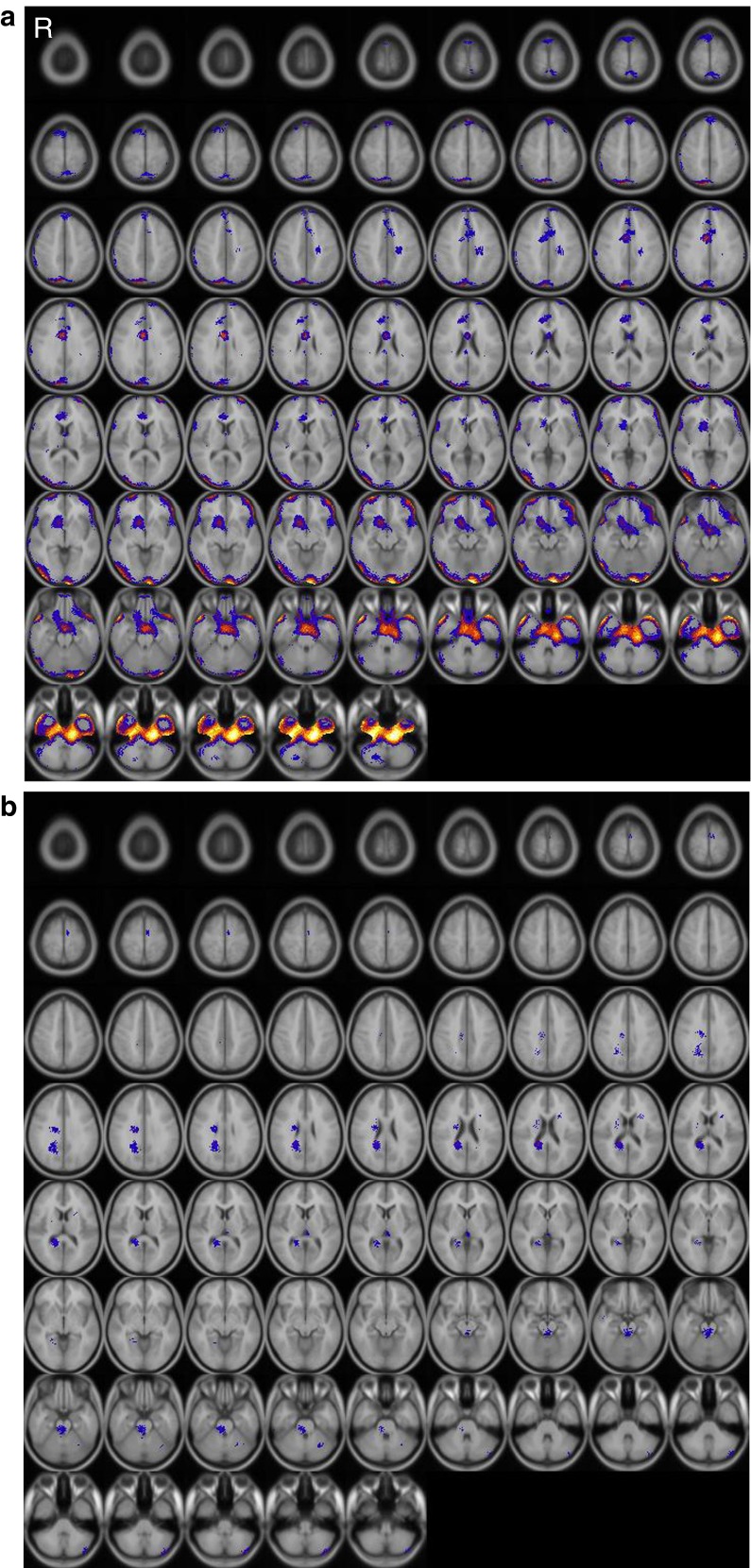

Baseline SPECT show relatively normal at each patient. After CIMT, regional cerebral perfusion increased in the both frontal lobes, left temporal lobe, both cerebellum and occipital lobes but decreased in the right frontotemporal area in patient 1. In patient 2, perfusion increased in the right frontal lobe, right limbic area and both occipital lobes, but decreased in the right white matter area. The SISCOM results are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

SISCOM result of patient 1 (Female, age 6, left hemiplegia). Brain areas showing significant changes in perfusion after CIMT. Regions of increased (a) and decreased perfusion (b) are indicated by color spots on the transaxial images. R, right

Fig. 2.

SISCOM result of patient 2 (Female, age 7, left hemiplegia). Brain areas showing significant changes in perfusion after CIMT. Regions of increased (a) and decreased perfusion (b) are indicated by color spots on the transaxial images. R, right

Improvements in upper-extremity function were found with the Jebsen hand function test and QUEST and, increased muscle activities in elbow extensors were observed with dynamic EMG during affected hand grip.

Discussion

CIMT is a rehabilitation method that improves motor recovery of the affected upper extremity in chronic stroke patients with mild-to-moderate hemiparesis [2, 12–15]. CIMT involves the intensive motor training of the stroke-affected limb coupled with restricted use of the unaffected limb [16, 17].

Recently, this method has been used in CP patients with hemiplegia. Intensive movement therapy appears to change local cerebral perfusion in areas known to participate in movement planning and execution. These changes might be a sign of active cortical reorganization processes after CIMT in young children with hemiplegic CP [18–20]. The mechanism of CIMT was not clearly defined, but increase of motivation, interlimb hypothesis, effect of intensive movement therapy, and brain flexibility have been assumed [16].

Many studies of fMRI or transcranial magnetic stimulation in chronic stroke patients have been conducted [16, 21, 22] and several studies with fMRI showed that cortical activation increases in the affected motor areas after CIMT [7, 21]. Berg et al. [23] reported that improved hand function after rehabilitation therapy is associated with increased fMRI activity in the premotor cortex and secondary somatosensory cortex contralateral to the affected hand and in the bilateral superior posterior cerebellar hemispheres. This suggests that altered recruitment of sensorimotor cortices and the cerebellum may contribute to recovery after this therapy.

PET and SPECT were also used to evaluate changes in cerebral metabolism and blood flow in adult stroke patients. These methods measure regional cerebral blood flow changes elicited by stimulation or activation of neurological or behavioral functions, and changes in regional cerebral blood flow reflect changes in underlying neuronal activity.

A previous study of SPECT in chronic stroke patients with CIMT showed increased perfusion in the precentral gyrus, premotor cortex (BA 6), frontal cortex, and superior frontal gyrus (BA 10) of the affected hemisphere and in the superior frontal gyrus (BA 6) and cingulated gyrus (BA 31) of the unaffected hemisphere [8]. In the cerebellum, increased perfusion was seen bilaterally. These areas are known to be involved with movement planning and execution. Decreased perfusion in the lingual gyrus (BA 18) in the affected hemisphere and in the middle frontal gyrus (BA 8/10), fusiform gyrus (BA 20), and inferior temporal gyrus (BA 37) in the unaffected hemisphere were observed. These areas might have been hyperperfused before therapy in an effort to compensate for disturbed activity of the affected hemisphere and possibly of the attentional drive from the unaffected hemisphere. Thus, decreased perfusion might indicate a change toward relative inactivity in the mentioned areas.

Functional brain reorganization in the bilateral sensory and motor systems was previously shown by PET [9, 24]. Wittenberg et al. [9] showed greater activation of the primary motor cortex, supplementary motor cortex and cerebellum in patients (before therapy) than in healthy volunteers when movement of the affected fingers was contrasted with rest.

Few imaging studies after CIMT have been conducted in children with CP. Few reports of the use of fMRI in pediatric CP patient have been published; cortical reorganization after CIMT was observed in a child with hemiplegia [20, 25]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging showed bilateral sensorimotor activation before and after therapy and a shift in the laterality index from ipsilateral to contralateral hemisphere after therapy [20]. We used SPECT to study changes in brain perfusion after CIMT in pediatric CP patients to evaluate the effects of CIMT. Intensive movement therapy appears to change local cerebral perfusion in areas known to participate in movement planning and execution. These changes might be a sign of active cortical reorganization processes after CIMT in young children with hemiplegic CP. We showed improved hand function after CIMT with corresponding changes in cerebral perfusion on SPECT. Regional cerebral perfusion increased in the frontal area, occipital area of the affected hemisphere and in the cerebellum and occipital, temporal areas of the unaffected hemisphere, but decreased in the frontotemporal and white matter area of the affected hemisphere. Two patients showed partially different perfusion changes. Kim et al. [7] also reported that the area and pattern of reorganization were patient dependent. We assumed that these differences depend on the degree of impairment, however, the factors influencing the individual pattern of reorganization may need to be further clarified.

Although it is inappropriate to compare our results with those of adult stroke patients, increased perfusion in various areas of the sensory and motor cortices known to participate in movement planning and execution, moreover improvement of motor function after CIMT also affects cortical reorganization in pediatric CP. Increased perfusion in unaffected side as well as affected side and in auditory and visual cortices indicate that reorganization can occur in unaffected side in pediatric patients and suggest good prognosis and has high compensatory potential [26, 27]. We reasoned that decreased perfusion is caused by relatively decreased activity of compensatory increase due to functional improvement of motor execution related area after CIMT.

Our cases showed changes in regional cerebral blood flow and maybe support the mechanism of cortical reorganization in pediatric CP patients after CIMT, however further studies are needed including large number of patients and comparing with fMRI study to determine the role of the SPECT.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the 2012 Yeungnam University Research Grant.

References

- 1.van Munster JC, Maathuis KG, Haga N, Verheij NP, Nicolai JP, Hadders-Algra M. Does surgical management of the hand in children with spastic unilateral cerebral palsy affect functional outcome? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:385–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taub E, Miller NE, Novack TA, Cook EW, 3rd, Fleming WC, Nepomuceno CS, et al. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rostami HR, Azizi Malamiri R. Effect of treatment environment on modified constraint-induced movement therapy results in children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(1):40–44. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.585214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoare B, Imms C, Carey L, Wasiak J. Constraint-induced movement therapy in the treatment of the upper limb in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: a Cochrane systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:675–685. doi: 10.1177/0269215507080783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakzewski L, Carlon S, Shields N, Ziviani J, Ware RS, Boyd RN. Impact of intensive upper limb rehabilitation on quality of life: a randomized trial in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:415–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall RS, Perera GM, Lazar RM, Krakauer JW, Constantine RC, DeLaPaz RL. Evolution of cortical activation during recovery from corticospinal tract infarction. Stroke. 2000;31:656–661. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YH, Park JW, Ko MH, Jang SH, Lee PK. Plastic changes of motor network after constraint-induced movement therapy. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:241–246. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kononen M, Kuikka JT, Husso-Saastamoinen M, Vanninen E, Vanninen R, Soimakallio S, et al. Increased perfusion in motor areas after constraint-induced movement therapy in chronic stroke: a single-photon emission computerized tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1668–1674. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittenberg GF, Chen R, Ishii K, Bushara KO, Eckloff S, Croarkin E, et al. Constraint-induced therapy in stroke: magnetic-stimulation motor maps and cerebral activation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2003;17:48–57. doi: 10.1177/0888439002250456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang LT. A method for attenuation correction in radionuclide computed tomography. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1978;25:638–43. doi: 10.1109/TNS.1978.4329385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haga N, van der Heijden-Maessen HC, van Hoorn JF, Boonstra AM, Hadder-Algra M. Test-retest and inter-and intrareliability of the quality of the upper-extremity skills test in preschoolage children with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1686–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkel A, Kopp B, Muller G, Villringer K, Villringer A, Taub E, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy for motor recovery in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:624–628. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miltner WH, Bauder H, Sommer M, Dettmers C, Taub E. Effects of constraint-induced movement therapy on patients with chronic motor deficits after stroke: a replication. Stroke. 1999;30:586–592. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winstein CJ, Prettyman MG. Constraint-induced therapy for functional recovery after brain injury: unraveling the key ingredients and mechanisms. In: Baudry M, Bi X, Schreiber SS, editors. Synaptic plasticity: Basic mechanisms to clinical applications. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2005. pp. 281–328. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf SL. Revisiting constraint-induced movement therapy: are we too smitten with the mitten? Is all nonuse “learned”? and other quandaries. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1212–1223. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawaki L, Butler AJ, Leng X, Wassenaar PA, Mohammad YM, Blanton S, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy results in increased motor map area in subjects 3 to 9 months after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22:505–513. doi: 10.1177/1545968308317531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaechter JD, Kraft E, Hilliard TS, Dijkhuizen RM, Benner T, Finklestein SP, et al. Motor recovery and cortical reorganization after constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke patients: a preliminary study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2002;16:326–338. doi: 10.1177/154596830201600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charles J, Gordon AM. A critical review of constraint-induced movement therapy and forced use in children with hemiplegia. Neural Plast. 2005;12:245–261. doi: 10.1155/NP.2005.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon AM, Charles J, Wolf SL. Methods of constraint-induced movement therapy for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: development of a child-friendly intervention for improving upper-extremity function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:837–844. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutcliffe TL, Gaetz WC, Logan WJ, Cheyne DO, Fehlings DL. Cortical reorganization after modified constraint-induced movement therapy in pediatric hemiplegic cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1281–1287. doi: 10.1177/0883073807307084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwakkel G, Meskers CG, van Wegen EE, Lankhorst GJ, Geurts AC, van Kuijk AA, et al. Impact of early applied upper limb stimulation: the EXPLICIT-stroke programme design. BMC Neurol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarkka IM, Kononen M, Pitkanen K, Sivenius J, Mervaalat E. Alterations in cortical excitability in chronic stroke after constraint-induced movement therapy. Neurol Res. 2008;30:504–510. doi: 10.1179/016164107X252519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansen-Berg H, Dawes H, Guy C, Smith SM, Wade DT, Matthews PM. Correlation between motor improvements and altered fMRI activity after rehabilitative therapy. Brain. 2002;125:2731–2742. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelles G, Jentzen W, Jueptner M, Muller S, Diener HC. Arm training induced brain plasticity in stroke studied with serial positron emission tomography. NeuroImage. 2001;13:1146–1154. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cope SM, Liu XC, Verber MD, Cayo C, Rao S, Tassone JC. Upper limb function and brain reorganization after constraint-induced movement therapy in children with hemiplegia. Dev Neurorehabil. 2010;13(1):19–30. doi: 10.3109/17518420903236247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eyre JA, Smith M, Dabydeen L, Clowry GJ, Petacchi E, Battini R, et al. Is hemiplegic cerebral palsy equivalent to amblyopia of the corticospinal system? Ann Neurol. 2007;62(5):493–503. doi: 10.1002/ana.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krägeloh-Mann I. Imaging of early brain injury and cortical plasticity. Exp Neurol. 2004;190(Suppl 1):S84–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]