Abstract

Uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma can have conventional imaging characteristics similar to those of other uterine tumors, such as leiomyoma, leiomyosarcomas or hemangioendothelioma. Uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma exhibiting increased fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (F-18 FDG) activity can be misdiagnosed. A 61-year-old woman who was diagnosed with uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma underwent F-18 FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) as a part of the pretreatment work up for surgery. F-18 FDG PET/CT showed an intense F-18 FDG uptake in the uterus in addition to increased F-18 FDG uptake at the paraaortic and aortocaval lymph nodes. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of intense F-18 FDG uptake in uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma in Korea.

Keywords: Uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma, F-18 FDG, PET/CT

Introduction

Primary uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma is a very rare malignant tumor of the vascular endothelium that occurs predominately in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with uterine bleeding and anemia. Uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma usually present as an enhanced huge mass on computed tomography (CT), and as a marked heterogeneity on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with focal areas of high signal intensity, known as the “cauliflower-like appearance” on gadolinium-enhanced MRI. .

We present the case of a uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma that was preoperatively detected byfluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (F-18 FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT.

Case Report

A previous healthy 61-year-old woman presented with a 3 week history of vaginal bleeding and lower abdominal pain, and was referred for F-18 FDG PET/CT as a part of her preoperative evaluation in December 2012.

The patient underwent F-18 FDG PET/CT scan after 8 hours of fasting. F-18 FDG PET/CT scan was performed at 60 min after the intravenous administration of 370 MBq (10 mCi) of F-18 FDG using a PET/CT scanner (Biograph 6, Siemens Healthcare, Germany). Non-enhanced CT was performed for attenuation correction, and subsequently, emission scanning was performed from the skull base to the proximal thigh.

F-18 FDG PET/CT showed a 12 × 10 × 9-cm sized, huge heterogenous hypermetabolic lesion at the uterus involving uterine cervix. The uterine mass showed a mild to moderately increased metabolic activity, with a focal active portion in the uterine fundus and posterolateral region of uterus. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of the most metabolically active portion was 6.5. On the other hand, the other part of the mass, including internal hemorrhagic or necrotic components, showed a relatively isometabolic or hypometabolic uptake pattern (Figs. 1 and 2). Other areas of focal hypermetabolic lesions in aortocaval and paraaortic lymph nodes with SUVmax of 4.7 were observed on F-18 FDG PET/CT.

Fig. 1.

Transaxial (a, b) and coronal (c, d) F-18 FDG PET/CT images show a 12 × 10 × 9-cm sized heterogeneously hypermetabolic lesion in the fundus and posterolateral region of uterus with SUVmax of 6.5 in 1 hour

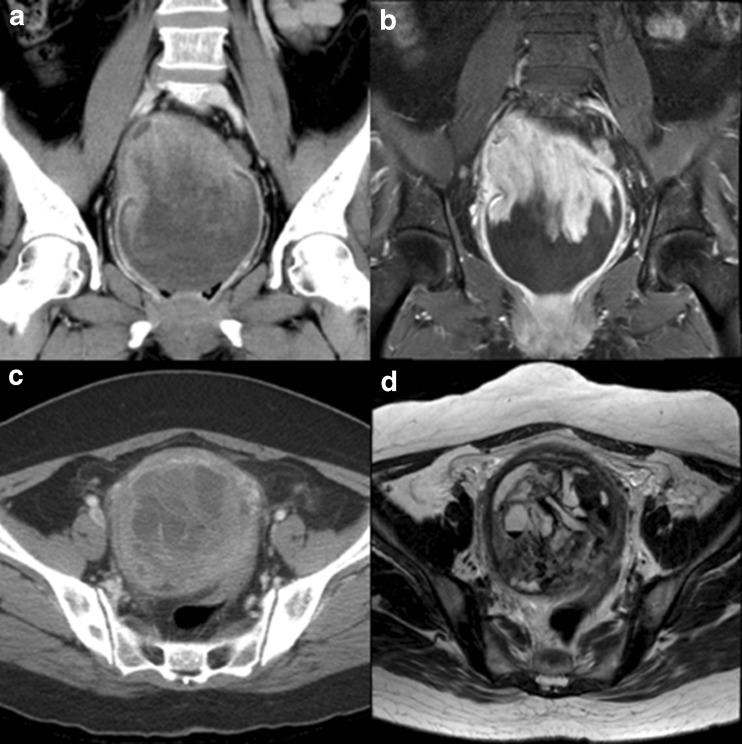

Fig. 2.

Coronal (a) and tranaxial (c) contrast-enhanced CT images show a enhanced mass in the fundus and posterolateral region of uterus. Coronal contrast-enhanced MRI (b) images show a high signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI in the utreus. Transaxial contrast-enhanced MRI (d) images show a high signal intensity, known as the “cauliflower-like appearance”on T2-weighted MRI in the utreus

A contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT demonstrated a 10-cm sized enhanced huge round heterogenous solid mass with internal multifocal cystic elements. A subsequent gadolinium-enhanced MRI confirmed the location of the uterine mass, with heterogenous T1 and T2 hyperintensity with cauliflower-like appearance. In addition, multifocal hemorrhagic components and internal cystic elements were detected.

A total hysterectomy with bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy, paraaortic lymph node dissection, and washing cytology was performed, and the tumor was removed with positive resection margin.

Macroscopically, the mass was poorly circumscribed tan to gray in color and it was friable, soft and partly hemorrhagic or necrotic. Invasion into adjacent structures was not seen. The tumor was diagnosed as epithelioid angiosarcoma. Microscopic examination showed the tumor was composed of marked pleomorphism and extensive tumor necrosis. The tumor involved serosa and myometrium of the uterus; its atypia of mitotic activity was more than 25 mitoses/10 high power fields. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis with positive staining of CD 10, CD 31, and CD 34, and negative staining of desmin and smooth muscle actin, which were expressed in muscle origin sarcoma.

The resected paraaortic lymph nodes had no evidence of metastasis.

The patient was undergoing radiotherapy and supportive care after surgery.

Discussion

Epithelioid angiosarcoma is a very rare tumor, accounting for less than 2 % of all sarcomas [1]. In contrast to conventional angiosarcoma, epithelioid angoisarcoma has been defined as a unique morphologic subtype of angiosarcoma, in which the malignant endothelial cells have a predominantly (or exclusively) epithelioid appearance [2]. Although epithelioid angiosarcomas can arise from any blood or lymph vessel, they most commonly arise on the face, scalp, [3] soft tissues, breast, spleen, liver and bone [4].

In the uterus, epithelioid angiosarcomas are extremely rare and have been reported to originate in the uterus, cervix, fallopian tube, ovary, parametrium, broad ligament and vagina [5]. What was to be later termed epithelioid angiosarcoma was first reported by Klob of Europe in 1864 [6].

Most women who develop uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma are postmenopausal. The commonest presenting symptom is abnormal vaginal bleeding that can range from menorrhagia and intermenstrual bleeding in premenopausal women to postmenopausal bleeding in the older patients. Subsequent to abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic examination detected an enlarged uterus presenting as a pelvic mass in almost all cases [7–11].

There are characteristic pathological findings grossly and microscopically. Grossly, the tumor is composed of whitish or grayish hemorrhagic tissue with areas of necrosis or calcification. It can sometimes have a lobulated pattern [9, 10].

Microscopically, the tumors contain irregular rudimentary vascular channels lined by atypical glandular or cuboidal cells. These lining cells show significant pleomorphism and nuclear hyperchromatism, with frequent mitotic figures. In addition, there are numerous solid areas with cells that exhibit eosinophilic cytoplasm with occasional vacuolization and round nuclei. Binucleated and multinucleated giant tumor cells are also present [7, 10].

Immunohistochemical staining is positive for the endothelial cell markers CD31,

CD34, and Factor VIII, supporting the diagnosis of primary uterine angiosarcoma [12], but muscle markers such as actin, desmin, and S-100 protein are usually all negative [13].

CT and MRI have been used to detect and evaluate uterine malignancies including uterine angiosarcoma; the imaging findings of these tumors using these modalities are relatively established in the literature. The different diagnosis for the CT or MRI findings of uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma includes leimyoma and leiomyosarcoma. Radiologically, the most helpful sign in the characterization of uterine angiosarcoma is marked heterogeneity on T2-weighted MRI with focal areas of high signal intensity, known as the “cauliflower-like appearance.” In addition, findings of a strongly enhanced lesion on gadolinium-enhanced T1 weighted MRI and contrast-enhanced CT also support the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. [4]

F-18 FDG PET/CT experiences in imaging angiosarcoma at anterior mediastinum, vessel, epicardium and adrenal gland were reported. [14–17] These reports have described variable F-18 FDG avidity of epithelioid angiosarcoma, which were mild to intense in F-18 FDG uptake (SUVmax up to 9.7). To our knowledge, the F-18 FDG PET/CT findings of primary uterine angiosarcoma have not been previously reported.

We suggest that the heterogenous F-18 FDG uptake on F-18 FDG PET/CT can be a characteristic finding of epithelioid angiosarcoma. This finding can be explained by aggressiveness and early spread pattern of tumor, heterogenous composition of hemorrhage, necrosis, cystic formation and solid portions in epithelioid angiosarcoma.

In summary, we reported a case of rare uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma that could result in false-positive interpretation by exhibiting F-18 FDG activity with a SUVmax similar to leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma and/or hemangioendothelioma at pretreatment evaluation of uterine malignancy. F-18 FDG PET/CT could be a useful tool to evaluate an aggressiveness and/or heterogeneity of uterine epithelioid angiosarcoma, and to early detection of regional or distant metastasis in initial staging.

References

- 1.Abrahamson TG, Stone MS, Piette WW. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Adv Dermatol. 2001;17:279–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CDM. Diagnostic histopathology of tumors. 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited; 2007. pp. 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao J, Dekoven JG, Beatty JD, Jones G. Cutaneous angiosarcoma as a delayed complication of radiation therapy for carcinoma of the breast. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:532–538. doi: 10.1067/S0190-9622(03)00428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konishi Y, Sato H, Fujimoto T, Tanaka H, Takahashi O, Tanaka T. A case of primary uterine angiosarcoma: magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography findings. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:280–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendez LE, Joy S, Angioli R, Estape R, Penalver M. Primary uterine angiosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:272–276. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klob: Cited by Horgan E. Hemangioma of Uterus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1930;50:990.

- 7.Tallini G, Price FV, Carcangiu ML. Epithelioid angiosarcoma arising in uterine leiomyomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;100:514–518. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/100.5.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drachenberg CB, Faust FJ, Borkowski A, Papadimitriou JC. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the uterus arising in a leiomyoma with associated ovarian and tubal angiomatosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:388–389. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinonez GE, Paraskevas MP, Diocee MS, Lorimer SM. Angiosarcoma of the uterus: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:90–92. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90633-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ongkasuwan C, Taylor JE, Tang CK, Prempree T. Angiosarcomas of the uterus and ovary: clinicopathologic report. Cancer. 1982;49:1469–1475. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820401)49:7<1469::AID-CNCR2820490726>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purola E, Strandell R. Haemangioendothelioma of the uterus. Ann Chir Gynaecol Fenn. 1967;56:102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konishi Y, Sato H, Fujimoto T, Tanaka H, Takahashi O, Tanaka T. A case of primary uterine angiosarcoma:magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography findings. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:254–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witkin GB, Askin FB, Geratz JD, Reddick RL. Angiosarcoma of the uterus: a light microscopic, immunohistochemical and Ultrastructural study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1987;6:176–184. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tane S, Tanaka Y, Tauchi S, Uchino K, Nakai R, Yoshimura M. Radically resected epithelioid angiosarcoma that originated in the mediastinum. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;59:503–506. doi: 10.1007/s11748-010-0710-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmehl J, Scharpf M, Brechtel K, Kalender G, Heller S, Claussen CD, Lescan M. Epithelioid angiosarcoma with metastatic disease after endovascular therapy of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:190–193. doi: 10.1007/s00270-011-0219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derlin T, Clauditz TS, Habermann CR. Adrenal epithelioid angiosarcoma metastatic to the epicardium: diagnosis by 18 F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:914–915. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318262af6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepoutre-Lussey C, Rousseau A, Al Ghuzlan A, Amar L, Hignette C, Cioffi A, et al. Primary adrenal angiosarcoma and functioning adrenocortical adenoma: an exceptional combined tumor. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:131–135. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]