Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of FP-CIT PET template-based quantitative analysis on F-18 FP-CIT PET in patients with de novo Parkinson’s disease (PD), compared with MR-based and manual methods. We also assessed the correlation of quantitative parameters of those methods with clinical severity of the disease.

Methods

Forty patients with de novo PD underwent both MRI and F-18 FP-CIT PET. Images were spatially normalized to a standardized PET template. Mean counts of 4 ROIs: putamen, caudate, occipital cortex and cerebellum, were obtained using the quantification program, Korean Statistical Probabilistic Anatomical Map (KSPAM). Putamen-to-caudate ratio (PCR), asymmetry index (ASI), specific-to-nonspecific ratios with two different references: to occipital cortex (SOR) and cerebellum (SCR) were compared. Parameters were also calculated from manually drawn ROI method and MR-coregistrated method.

Results

All quantitative parameters showed significant correlations across the three different methods, especially between the PET-based and manual methods. Among them, PET-based SOR and SCR values showed an excellent correlation and concordance with those of manual method. In relationship with clinical severity, only ASI achieved significantly inverse correlations with H&Y stage and UPDRS motor score. There was no significant difference between the quantitative parameters of both occipital cortex and cerebellum in all three methods, which implied that quantitation using PET-based method could be reproducible regardless of the reference region.

Conclusions

Quantitative parameters using FP-CIT PET template-based method correlated well with those using laborious manual method with excellent concordance. Moreover, PET-based quantitation was less influenced by the reference region than MR-based method. It suggests that PET-based method can provide objective and quantitative parameters quickly and easily as a feasible analysis in place of conventional method.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, F-18 FP-CIT PET, Template-based quantitative analysis, Korean statistical probabilistic anatomical map (KSPAM), Dopamine transporter (DAT)

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive damage of the dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra. Its functional neuroimaging has been developed to reveal the abnormalities in dopaminergic system of PD. Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) offered the opportunity of being an objective method to assess DAT availability. Many radiotracers have been also synthesized for those DAT imaging. Among them, N-3-fluoropropyl-2β-carboxymethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-nortropane, FP-CIT [1–5], is a high-affinity cocaine analog that binds specifically to DAT and suitable for both PET and SPECT imaging.

Fluorine-18 labeled FP-CIT is one of the widely used radiopharmaceuticals for DAT imaging, using the PET system which allows quantitative analysis with a better imaging quality and a higher count rate than the SPECT system. In current clinical practices, however, DAT images are generally interpreted by visual inspection [6, 7], thus, the results may be subjective and observer-dependent. Moreover, it can be difficult to identify the images with subtly localized or diffusely decreased FP-CIT uptake solely by the visual inspection. To quantify DAT activity, ROI method was used for data analysis, using fixed ROIs [8–11] or irregularly shaped ones with surface-fitting method [3, 12]. Manual delineation of slice-by-slice ROIs is laborious and time-consuming process and this is still dependent on the operator [13]. Moreover, it may be affected by signal loss of posterior putamen. In order to overcome these kinds of problems, there have been increased interests for the automatic approach which is accurate and reproducible [13–16].

Structural and functional brain maps provide effective information for the interpretation of complex brain data. Many methods including automated registration and segmentation have been developed to localize and display the functional brain regions. One of them is statistical probabilistic anatomical mapping (SPAM) [17–19]. SPAM is a well-known tool of an atlas-based volume of interest (VOI) to obtain the regional counts from the individual images which was spatially normalized into standardized brain templates. It can be used to delineate the brain regions statistically and objectively. However, it has not yet been established enough to yield the VOIs which are specific to FP-CIT PET.

Koo et al. [14] developed the standard templates of brain MRI and PET and statistical probabilistic maps for 89 brain regions of Korean healthy normal volunteers. A quantification program, called Korean SPAM (KSPAM), was developed by Lee et al. [15] to calculate the probability-weighted regional mean counts using Korean population data by Koo et al. We applied this automatic program to the quantification of DAT activity on F-18 FP-CIT PET. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the DAT density using SPAM on F-18 FP-CIT PET. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of FP-CIT PET template-based semiautomatic quantitative analysis in de novo idiopathic PD patients on F-18 FP-CIT PET, compared with MR-coregistrated and manually driven methods. For the purpose, we also assessed the correlations between the quantitative parameters using those methods and clinical measures of disease severity.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We retrospectively examined 40 consecutive de novo PD patients who underwent both MRI and F-18 FP-CIT PET/CT scans from June 2009 to June 2011. The diagnosis of idiopathic PD was confirmed by movement disorder specialists with general and neurological examinations according to the criteria of the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank. Patients were excluded if they had a history of head trauma, stroke, dementia, or other kinds of psychological disorders. Only patients who had not yet started any dopaminergic or anti-Parkinson’s medications were included in this study. Clinical severity of the disease was assessed with Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) stage [20], the motor part (III) of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) [21] and the duration of symptoms. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital.

Radiopharmaceutical Synthesis

F-18 FP-CIT was synthesized by electrophilic fluorination of FP-CIT (FutureChem, Seoul, Korea) with a protic solvent (t-butanol or t-amyl alcohol) as a reaction solvent and N-[3’-(tosyloxy)propyl]-2β -carbomethoxy-3β -(4’-iodophenyl)nortropane as a precursor, according to the method reported previously [22, 23]. Mean decay-corrected radiochemical yield was 42.5 ± 10.9 % after high-performance liquid chromatography purification. Its mean specific activity was 64.4 ± 4.5 GBq/mmol at the end of synthesis and the radiochemical purity was 98.5 ± 1.2 %.

F-18 FP-CIT PET/CT Imaging Acquisition

Patients received an intravenous injection of 185 MBq (5.0 mCi) of F-18 FP-CIT and then rested for approximately 2 h before undergoing scans. PET scans were acquired for 10 min with the patient’s eyes open in a dimly lit room with minimal auditory stimulation. Imaging acquisition was performed using a whole-body, high-resolution PET-CT scanner (Gemini TF, Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH) from the skull vertex to the base. PET scanner generates 90 contiguous transverse slices with an intrinsic resolution of 4.4 mm full-width half-maximum (FWHM) in all directions and an axial field of view of 18 cm. Attenuation correction was performed using a low-dose CT scan, 16-slice multidetector helical CT unit using the following parameters: 120 kVp; 30 mA; 0.5-s rotation time; 1.5-mm slice collimation, 2-mm scan reconstruction, with a reconstruction index of 2 mm; 60-cm field of view; 512 × 512 matrix. Acquired data were reconstructed iteratively using a three-dimensional row action maximum-likelihood algorithm (RAMLA) with low-dose CT datasets for attenuation correction in 3D mode.

Data Processing and Quantitation

Manual and two different semiautomatic methods were used in this study. Image processing and calculation were performed in Statistical Parametric Mapping 2 software (SPM2, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College of London, UK) in conjunction with MATLAB version 7.0 (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA) and FIRE (Functional Image REgistration, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea) program [24]. All the image datasets of CTI format were converted to ANALYZE format using the software MRIcro (www.mricro.com, Rorden and Brett, Columbia, SC).

Uptake indexes were obtained as mean counts per pixel, taking the specific area on striatum and the nonspecific areas on both occipital cortex and cerebellum into account. Putamen to caudate ratio (PCR) and asymmetry index (ASI) were measured as outcome parameters. Additionally, a ratio of specific to nonspecific uptake was calculated. These ratios were known as proportional to the DAT density and were derived by dividing the mean counts of each striatal region by average counts in the nonspecific reference regions according to the formulae:

|

|

|

|

Manual ROI Method

Using the FIRE program, the transaxial slices of PET images and corresponding T1 MR images were manually corrected for possible transverse and coronal inclinations and reoriented parallel to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line. We hand-drew ROIs on the PET frames, which are described in Fig. 1, using the reoriented MR images as an anatomical reference. The ROIs were drawn on the left and right sides of caudate, putamen, occipital cortex and cerebellum in each hemisphere on the three adjacent transaxial slices where the striata were best seen.

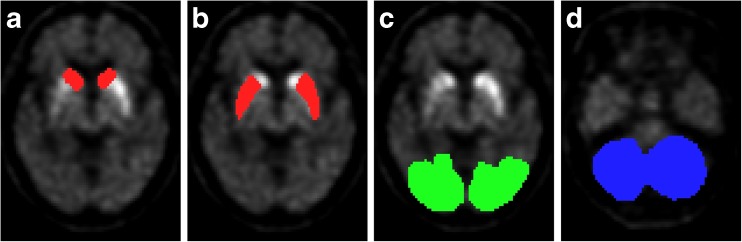

Fig. 1.

Irregular shaped ROIs were manually drawn on the caudate (a), putamen (b), occipital lobe (c) and cerebellum (d) by the surface-fitting method

We also assessed the reproducibility of the manual method based on intra- and interoperator reliability for the ROI technique. For intra-operator variability, the measurements were repeated after an interval of 1 month by the same investigator, with no access to the initial results when performing the second ones. Two nuclear medicine physicians independently processed each dataset under the same setting for the inter-operator variability.

Semiautomatic MR and PET Template-Based VOI Methods

There are two different semiautomatic methods replacing ROI method. Firstly, PET images were coregistrated to their own T1-weighted MR images which could well visualize the boundaries of the grey and white matter with a better resolution. Then, fused PET/MR images were spatially normalized to an MRI template from ICBM using SPM2. Secondly, PET images were directly normalized into a standard stereotactic space [25] using the published brain template for F-18 FP-CIT binding [1]. Imaging processes are described in Fig. 2.

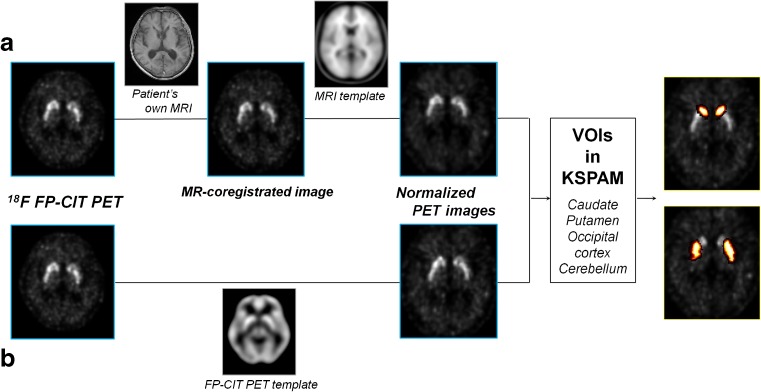

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of semiautomatic analysis. F-18 FP-CIT PET images are coregistrated to their own T1-weighted MR images and then spatially normalized to an MRI template (a). PET images are also directly normalized using the F-18 FP-CIT template (b). These two normalized PET images are applied to the automatic quantitative program, Korean Structural Statistical Probabilistic Anatomical Map (KSPAM). The mean counts of VOIs including caudate, putamen, occipital cortex and cerebellum obtained by using SPM2

To calculate the PET counts objectively, we applied the automatic quantitative program, Korean Structural Statistical Probabilistic Anatomical Map (KSPAM) [13], which is based on Korean standard brain atlas [14]. KSPAM consists of 89 volumes of interest (VOIs) images, including putamen, caudate nucleus, occipital cortex and cerebellum. Each image consists of the probabilities from 0 to 1 that belong to specific regions. And the mean counts of each VOI were multiplied using KSPAM. This calculation process was performed using SPM2.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to find the differences across the three methods. Relationships between the parameters from each method were determined with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (rho, rs). It was also used to assess the correlation between the parameters and clinical measures. Bland–Altman plots and concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) were evaluated for agreement analysis. In addition, interoperator and intra-operator reliability were estimated for reproducibility of manual ROI method using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) software was used for statistical analysis, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

Forty consecutive PD patients (14 men and 26 women, mean age of 68.7 years) were enrolled. All patients were confirmed by movement disorder specialists (Lee CN and Park KW) with a consensus. Disease severity was evaluated with H&Y stage as stage 1 of 13 patients, stage 1.5 of 2, stage 2 of 12, stage 2.5 of 6, and stage 3 of 7. The mean and SD of UPDRS motor score and the duration of symptoms were 20.2 ± 9.9 and 10 ± 13 months, respectively. No patients had abnormal finding on brain MRI, including the evidence of brain ischemia. The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.7 ± 9.3 [41–82]a |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (35 %), |

| Female | 26 (65 %) |

| H & Y stage | 1.90 ± 0.74a |

| Stage 1 | 13 (33 %) |

| Stage 1.5 | 2 (5 %) |

| Stage 2 | 12 (30 %) |

| Stage 2.5 | 6 (15 %) |

| Stage 3 | 7 (17 %) |

| UPDRS motor (III) score | 20.2 ± 9.9 [4–41]a |

| Symptom duration (months) | 19 ± 13 [3–48]a |

amean ± standard deviation [range]

Uptake Indexes

Uptake indexes obtained from the three different analyses, that is, PET-based, MR-based and manual methods had significant differences between them (P < 0.001) as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3. Among those comparisons, PET-based method showed similar ranges of values as manual method in most of the evaluated parameters. PET-based SOR and SCR were 1.87 ± 0.51 and 2.46 ± 0.69, of which figures were higher than the values from manual method (1.69 ± 0.46 and 2.21 ± 0.62). On the other hand, MR-based method showed broader ranges of distribution and higher values of means in PCR and ASI (1.07 ± 0.28 and 14.41 ± 14.16), compared to the rest two methods. And as for SOR and SCR values (1.10 ± 0.38 and 1.57 ± 0.54), those of MR-based method were lower than the others. In addition, manual contouring method was reproducible with a fair to high ICC values (0.70–0.94) in both inter- and intra-operator. Reliability was lower in PCR and ASI, however SOR and SCR showed good repeatability within and between the observers despite its subjectivity. The results for intra- and inter-operator reliability of each parameter are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Parameters of F-18 FP-CIT uptake of each method

| PET-based | MR-based | Manual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 1.07 ± 0.28 | 0.90 ± 0.15 |

| ASI | 8.79 ± 6.08 | 14.41 ± 14.16 | 12.24 ± 8.45 |

| SOR | 1.87 ± 0.51 | 1.10 ± 0.38 | 1.69 ± 0.46 |

| SCR | 2.46 ± 0.69 | 1.57 ± 0.54 | 2.21 ± 0.62 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation

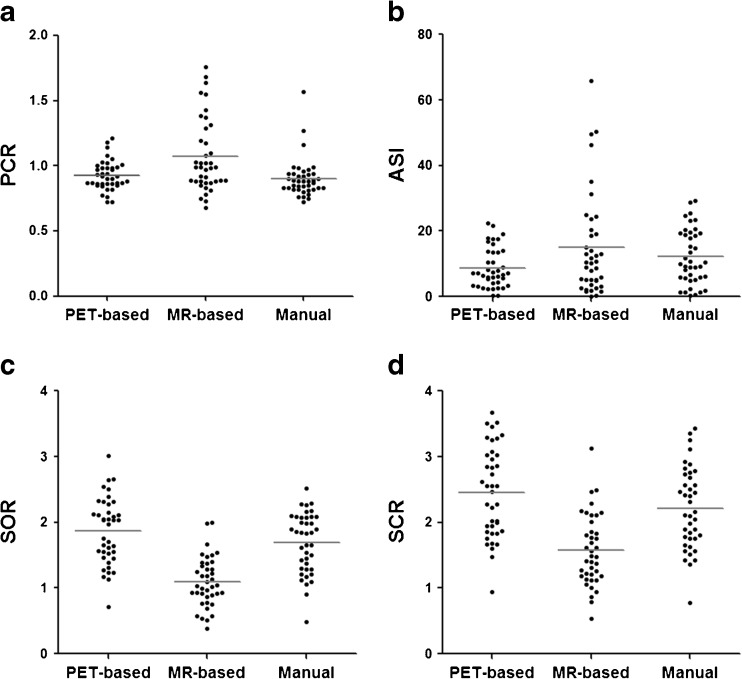

Fig. 3.

Scatterplots of PCR (a), ASI (b), SOR (c) and SCR (d) between three methods. PET-based method showed similar ranges of values with manual method in most of the evaluated parameters. Horizontal bars indicate means

Table 3.

Evaluation of reproducibility obtained from manually-driven method

| Intra-operator reliability | Inter-operator reliability | |

|---|---|---|

| PCR | 0.70 (0.46–0.84) | 0.78 (0.61–0.88) |

| ASI | 0.73 (0.51–0.85) | 0.76 (0.57–0.87) |

| SOR | 0.90 (0.81–0.94) | 0.83 (0.68–0.90) |

| SCR | 0.94 (0.89–0.97) | 0.91 (0.84–0.95) |

Values are intraclass correlation coefficients, and data in parentheses are 95 % limits of agreement

Feasibility of FP-CIT PET Template-Based Method

We found statistically significant correlation between all parameters obtained from three different methods. Coefficients of correlation are shown in Table 4. PET-based method showed good correlation with manual method, which was more remarkable in ASI (rs = 0.63, P < 0.001), SOR (rs = 0.89, P < 0.001) and SCR (rs = 0.94, P < 0.001). When we compared PET-based method to manual method, SOR and SCR values yielded good agreements with high CCC values (CCC = 0.83, 0.87, respectively). Bland-Altman plots also showed consistent results with concordance analysis. In the relationship of PET and MR-based methods, we found better correlation and agreement in PCR (rs = 0.77, P < 0.001, and CCC = 0.43) than the former comparison. They also had fair agreement with each other in SOR and SCR (CCC = 0.34, both). Concordance of measuring the ratios of striatum and cerebellum in PET and MR was lower than those in PET and manual methods. In regards to the reference region, specific to nonspecific ratios with both occipital cortex and cerebellum showed excellent CCC values and coherent Bland-Altman plots, when compared PET-based to both manual and MR-based method. Coefficients of concordance and Bland-Altman analysis are described in Table 5.

Table 4.

Correlations of F-18 FP-CIT parameters between the methods

| PET-based vs. manual | PET-based vs. MR-based | MR-based vs. manual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | 0.32 (P = 0.045)* | 0.77 (P < 0.001)* | 0.27 (P = 0.088) |

| ASI | 0.63 (P < 0.001)* | 0.52 (P = 0.001)* | 0.38 (P = 0.015)* |

| SOR | 0.89 (P < 0.001)* | 0.89 (P < 0.001)* | 0.77 (P < 0.001)* |

| SCR | 0.94 (P < 0.001)* | 0.72 (P < 0.001)* | 0.63 (P < 0.001)* |

Values are Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rs). Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05)

Table 5.

Agreement levels between the methods

| PET-based vs. manual | PET-based vs. MR-based | |

|---|---|---|

| PCR | ρc = 0.30 | ρc =0.43 |

| 0.02 (−0.03/0.07) | −0.15 (−0.21/−0.08) | |

| ASI | ρc =0.539 | ρc =0.31 |

| −3.45 (−5.56/−1.35) | −6.13 (−10.45/−1.82) | |

| SOR | ρc =0.83 | ρc =0.34 |

| 0.17 (0.10/0.25) | 0.77 (0.69/0.85) | |

| SCR | ρc =0.87 | ρc =0.34 |

| 0.25 (0.17/0.32) | 0.89 (0.73/1.04) |

Lin’s concordance correlation coefficients (ρc) are shown in first row of each parameter

Results from Bland-Altman approach are given in second row, and values are mean differences with 95 % limits of agreement in parentheses

Correlation with Clinical Severity

Most of the correlations didn’t show statistical significance except for ASI value. PET-based ASI was inversely and significantly correlated with UPDRS motor score (rs = −0.31, P = 0.048). For the correlative analysis of H&Y stage, as there were only 2 patients in H&Y 1.5, we regrouped the patients into three groups: 1.0 and 1.5 for stage 1+; 2.0 and 2.5 for stage 2+; and stage 3. ASI achieved significant negative correlation with simplified H&Y stage groups in all three methods (rs = −0.35, −0.34, −0.43 for PET, MR and manual method, respectively). However, there was no additional significant parameter correlating with clinical measures. Correlations of significant parameters with clinically measured severity are shown in Fig. 4.

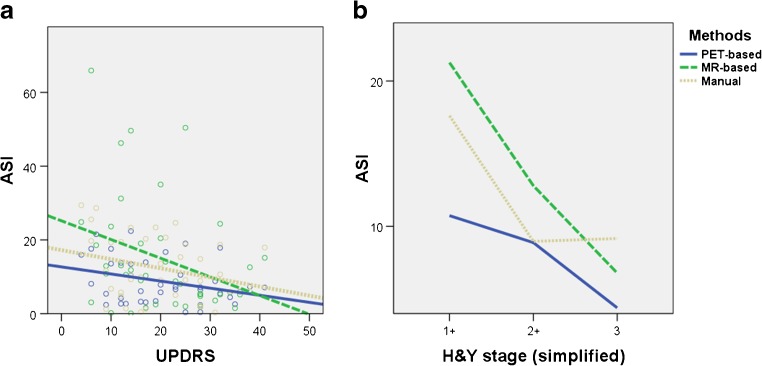

Fig. 4.

Correlation of ASI values with clinical measurements. ASI values are plotted against the clinical measurements: UPDRS motor score (a), and simplified H&Y stage (b). PET-based ASI shows an inverse regression line with UPDRS motor score (r s = −0.31, P = 0.048). ASI tends to decrease with increasing H&Y stage in all three methods with correlation coefficients of −0.35, −0.34, −0.43, respectively. (P = 0.027, 0.032, 0.006, respectively). Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05)

Discussion

In this study, we examined a group of de novo PD patients and compared the striatal uptake values from three different methods. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that PET template-based semiautomatic method was reliable and reproducible in measuring the DAT density of de novo PD patients. PET-based semiautomatic quantitative values were comparable with those estimated from MR-based and manual method, with good correlation and agreement between the methods. These results indicate that this automated analysis for basal ganglia quantitation works properly and also saves time and efforts in clinical fields.

There are several studies which used the semiautomatic analysis to evaluate the DAT density of PD patients in comparison with manual ROI method. In an article published by Takada et al. [26], the semiautomatic method using a calculation program was compared with the manual ROI method, in which they drew the irregular-shaped regions on coregistrated MR/SPECT images. It showed fair linear correlation with manual method, which was useful to discriminate between PD and essential tremors (ET) patients. Calvini et al. [27] reported that the automatic VOI showed significantly lower striatal uptake in PD patients versus controls and also correlated with clinical score far more than conventional ROI method.

Our study suggested that the semiautomatic PET-based method was useful for the quantification of F-18 FP-CIT uptake. It showed good correlation and agreement with manual method, which was remarkable in specific to nonspecific ratios. It also showed a significant correlation with clinical severity than the other two methods. However, the correlation and consistency were lower in PCR between PET-based and manual method and we found rather better results from comparing with PET and MR-based PCR values. These are speculated to be caused by the differences in the definition of ROI and VOI. Semiautomatic method had three-dimensional volume of striatum, whereas the manual method calculated the counts on only three slices of PET images. It was possible that the ROI of striatum, especially in caudate nucleus, could not represent the true counts of whole striatum. Also, the correlation and concordance of MR-based method generally decreased more, compared to the rest of two methods. It seemed that the raw data could have been distorted through a couple of imaging processes, which led to unsatisfied results. Consequently, semiautomatic PET-based method made it possible to save time and improve accuracy without altering the basic quality of images as compared to the conventional ROI analysis. It might be of value for quantitative analysis of DAT imaging in routine clinical fields.

There had been some controversies concerning the relationship between DAT imaging and clinical measures of disease severity. Many studies [3, 7, 28–30] reported a significant inverse correlation of striatal FP-CIT uptake or ratio with the clinical motor severity. On the other hand, some other studies [6, 31] mentioned that there was no significant clinical correlation. In our data, we found that the striatal asymmetry was inversely correlated with the disease severity of both H&Y stage and UPDRS motor score, supporting that the more the disease progressed, the similar both striatal uptake appeared. Specific to nonspecific ratios, SOR and SCR, tended to describe inverse correlation with clinical measures, but they couldn’t achieve statistical significance. More investigations and follow-up studies are needed to establish the significance of quantitative measurement.

We also compared quantitative values of PET-based method using two different nonspecific areas and found a good agreement between the occipital cortex and cerebellum. It was presumed that the choice of nonspecific area might influence the calculation of DAT activity, because FP-CIT is not fully affinitive to DAT and known to partially bind to serotonin transporter (SERT) as well. In a study by Ortega Lozano et al. [9], they chose three nonspecific areas of cerebellum, occipital cortex and midbrain according to the different concentration of serotonin receptors and found the greatest predictive capacity to differentiate the Parkinsonism was the occipital cortex. In our results, there was no significant difference of reference region, which implied that all the methods were reliable and reproducible enough to measure the counts of occipital cortex and cerebellum. In further analysis of Bland–Altman plots, however, we recognized that the mean difference of measuring occipital cortex was much closer to zero than cerebellum in comparison of PET-based method vs. both manual and MR-based method. In other words, though the difference of the reference regions were not significant, it could be preferable to choose the occipital cortex considering the slightly better performance in SOR values.

Our study had the most fundamental limitation that there was no reference “gold standard” in diagnosing PD. In clinical situation, evaluation of PD is widely dependent on clinical assessments, therefore, we had to compare the quantitative values of our methods with those scores of clinical severity. However, the degree of clinical severity, which is commonly used with H&Y stage scale and UPDRS score, might not strictly represent the true severity. These could be one of the reasons that we couldn’t find the significant correlation with SOR and SCR values.

Another limitation of this study was that we did not compare the quantitative parameters to the normal controls or other groups of different disease entities. Our study was aimed to evaluate the feasibility of PET-based semiautomatic analysis. However, if we took the normal reference data into consideration, it could help us to comprehend the results of our study and also strengthen the value of PET-based method in DAT imaging. Further studies would be needed.

Conclusion

FP-CIT PET template-based semiautomatic method was useful to estimate the extents of nigrostriatal dopaminergic loss in patients with de novo PD. It showed a good correlation with manual ROI method with a very high degree of concordance. ASI calculated by PET-based method was also a significant clinical parameter predicting the disease severity. Above all, PET-based method quantitatively exhibited the striatal uptake in a quick way with reducing the efforts. It seemed that the PET template-based semiautomatic method can be a feasible method enough to take the place of laborious conventional analysis and provide objective and comparable parameters to explore and differentiate the disease in clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by Korea University Research Special Grants (2011-K1131781, 2011-K1132941). We had no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

References

- 1.Ma Y, Dhawan V, Mentis M, Chaly T, Spetsieris PG, Eidelberg D. Parametric mapping of [18F]FPCIT binding in early stage Parkinson’s disease: a PET study. Synapse. 2002;45:125–133. doi: 10.1002/syn.10090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazumata K, Dhawan V, Chaly T, Antonini A, Margouleff C, Belakhlef A, et al. Dopamine transporter imaging with fluorine-18-FPCIT and PET. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1521–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Zuo CT, Jiang YP, Guan YH, Chen ZP, Xiang JD, et al. 18F-FP-CIT PET imaging and SPM analysis of dopamine transporters in Parkinson’s disease in various Hoehn & Yahr stages. J Neurol. 2007;254:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh M, Kim JS, Kim JY, Shin KH, Park SH, Kim HO, et al. Subregional patterns of preferential striatal dopamine transporter loss differ in Parkinson disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and multiple-system atrophy. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:399–406. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh JK. Clinical significance of F-18 FP-CIT dual time point pet imaging in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;45:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s13139-011-0110-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun HJ. Clinical significance of 123I-IPT SPECT for the diagnosis of the Parkinson’s disease. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2003;34:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benamer TS, Patterson J, Grosset DG, Booij J, de Bruin K, van Royen E, et al. Accurate differentiation of parkinsonism and essential tremor using visual assessment of [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT imaging: the [123I]-FP-CIT study group. Mov Disord. 2000;15:503–510. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200005)15:3<503::AID-MDS1013>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acton PD, Newberg A, Plossl K, Mozley PD. Comparison of region-of-interest analysis and human observers in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease using [99mTc]TRODAT-1 and SPECT. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:575–585. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/3/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortega Lozano SJ, Martinez Del Valle Torres MD, Ramos Moreno E, Sanz Viedma S, Amrani Raissouni T, Jimenez-Hoyuela JM. Quantitative evaluation of SPECT with FP-CIT. Importance of the reference area. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2010;29:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tossici-Bolt L, Hoffmann SM, Kemp PM, Mehta RL, Fleming JS. Quantification of [123I]FP-CIT SPECT brain images: an accurate technique for measurement of the specific binding ratio. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1491–1499. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filippi L, Bruni C, Padovano F, Schillaci O, Simonetti G. The value of semi-quantitative analysis of 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in evaluating patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neuroradiol J. 2008;21:505. doi: 10.1177/197140090802100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim BS. The discriminating nature of dopamine transporter image in Parkinsonism: the competency of dopaminergic transporter imaging in differential diagnosis of Parkinsonism: 123I-FP-CIT SPECT study. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;41:272–279. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JS. Quantification of brain images using Korean standard templates and structural and cytoarchitectonic probabilistic maps. Korean J Nucl Med. 2004;38:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo BB. Developing a Korean standard brain atlas on the basis of statistical and probabilistic approach and visualization tool for functional image analysis. Korean J Nucl Med. 2003;37:162–170. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JS, Lee DS. Analysis of functional brain images using population-based probabilistic atlas. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2005;1:81–87. doi: 10.2174/1573405052953056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherfler C, Seppi K, Donnemiller E, Goebel G, Brenneis C, Virgolini I, et al. Voxel-wise analysis of [123I]beta-CIT SPECT differentiates the Parkinson variant of multiple system atrophy from idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 7):1605–1612. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi JY, Lee KH, Na DL, Byun HS, Lee SJ, Kim H, et al. Subcortical aphasia after striatocapsular infarction: quantitative analysis of brain perfusion SPECT using statistical parametric mapping and a statistical probabilistic anatomic map. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:194–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee TH, Kim SJ, Kim IJ, Kim YK, Kim DS, Park KP. Statistical parametric mapping and statistical probabilistic anatomical mapping analyses of basal/acetazolamide Tc-99 m ECD brain SPECT for efficacy assessment of endovascular stent placement for middle cerebral artery stenosis. Neuroradiol. 2007;49:289–298. doi: 10.1007/s00234-006-0188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee DS, Lee JS, Kang KW, Jang MJ, Lee SK, Chung JK, et al. Disparity of perfusion and glucose metabolism of epileptogenic zones in temporal lobe epilepsy demonstrated by SPM/SPAM analysis on 15O water PET, [18F]FDG-PET, and [99mTc]-HMPAO SPECT. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1515–1522. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.21801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/WNL.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fahn S, Elton R, Committee. MotUD . The unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: Fahn SMC, Calne DB, Goldstein M, editors. Recent developments in Parkinson’s disease. Florham Park: Macmillan Healthcare Information; 1987. pp. 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SJ, Oh SJ, Chi DY, Kang SH, Kil HS, Kim JS, et al. One-step high-radiochemical-yield synthesis of [18F]FP-CIT using a protic solvent system. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SJ, Oh SJ, Moon WY, Choi MS, Kim JS, Chi DY, et al. New automated synthesis of [18F]FP-CIT with base amount control affording high and stable radiochemical yield: a 1.5-year production report. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JS, Park KS, Lee DS, Lee CW, Chung JK, Lee MC. Development and applications of a software for Functional Image Registration (FIRE) Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;78:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takada S, Yoshimura M, Shindo H, Saito K, Koizumi K, Utsumi H, et al. New semiquantitative assessment of 123I-FP-CIT by an anatomical standardization method. Ann Nucl Med. 2006;20:477–484. doi: 10.1007/BF02987257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calvini P, Rodriguez G, Inguglia F, Mignone A, Guerra UP, Nobili F. The basal ganglia matching tools package for striatal uptake semi-quantification: description and validation. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1240–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishikawa T, Dhawan V, Kazumata K, Chaly T, Mandel F, Neumeyer J, et al. Comparative nigrostriatal dopaminergic imaging with iodine-123-beta CIT-FP/SPECT and fluorine-18-FDOPA/PET. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1760–1765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asenbaum S, Brücke T, Pirker W, Podreka I, Angelberger P, Wenger S, et al. Imaging of dopamine transporters with iodine-123-beta-CIT and SPECT in Parkinson’s disease. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rinne JO, Ruottinen H, Bergman J, Haaparanta M, Sonninen P, Solin O. Usefulness of a dopamine transporter PET ligand [18F]β-CFT in assessing disability in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:737–741. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.6.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hubbuch M, Farmakis G, Schaefer A, Behnke S, Schneider S, Hellwig D, et al. FP-CIT SPECT does not predict the progression of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Eur Neurol. 2011;65:187–192. doi: 10.1159/000324732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]