Abstract

Female fertility is highly dependent on successful regulation of energy metabolism. Central processes in the hypothalamus monitor the metabolic state of the organism and, together with metabolic hormones, drive the peripheral availability of energy for cellular functions. In the ovary, the oocyte and neighboring somatic cells of the follicle work in unison to achieve successful metabolism of carbohydrates, amino acids, and lipids. Metabolic disturbances such as anorexia nervosa, obesity, and diabetes mellitus have clinically important consequences on human reproduction. In this article, we review the metabolic determinants of female reproduction and their role in infertility.

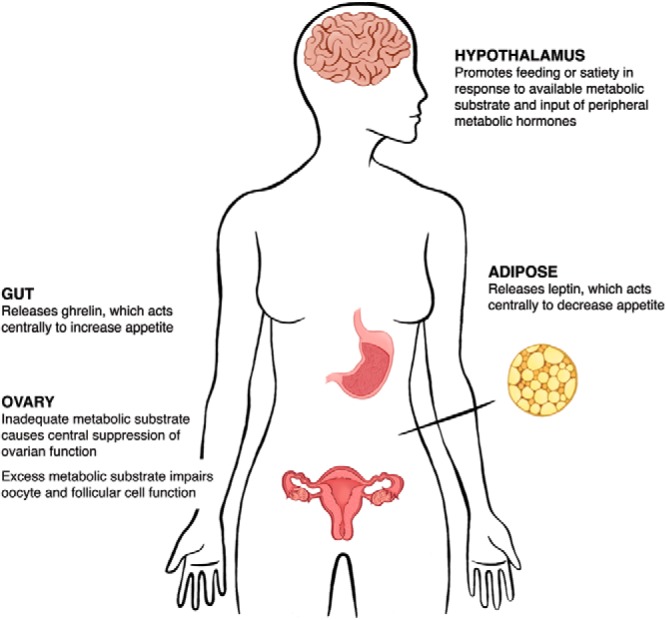

In the female, reproduction is a process requiring a large metabolic investment, with increased energy needs for the organism over the duration of a lengthy gestation and period of lactation. As such, the function of the female reproductive axis is influenced by the metabolic milieu of the organism, both at the whole-body and cellular level. Central regulation of metabolism, via the interplay between metabolic hormones and signals from specific neurons in the hypothalamus, impacts the amount and type of metabolic substrate available to peripheral organs, including the ovary (Figure 1). In the ovary, cellular metabolism relies upon the unique relationship between the oocyte and the surrounding follicular cells, using juxtacrine and paracrine interactions. After the oocyte is fertilized and an early preimplantation embryo is established, the need for tight metabolic control persists in order to avoid embryonic anomalies and demise.

Figure 1.

The regulation of metabolism is an essential component of successful female fertility. The hypothalamus promotes feeding or satiety in response to the availability of metabolic substrate. This central control of appetite is further regulated by the peripheral regulatory hormones leptin, primarily released from adipose tissue, and ghrelin, derived from the gut, which act directly on hypothalamic neurons to suppress and promote appetite, respectively. The resulting effects of these central and peripheral interactions optimally yield a metabolic context amenable to fertility. However, both inadequate and excess metabolic substrate can impair female fertility via direct and indirect effects on ovarian function.

The consequences of metabolic perturbations on reproductive physiology are borne out in several disease states, including anorexia nervosa (AN), diabetes, and obesity. In AN, the associated caloric restriction results in central suppression of the female reproductive axis. On the contrary, the caloric excesses of diabetes and obesity largely impair reproduction at the level of the cumulus-oocyte complex and in early embryonic development, where the excess metabolites lead to mitochondrial abnormalities and meiotic defects. Through the course of this review, we will discuss the regulation of metabolism in the female reproductive axis and summarize the data describing the clinical affect of alterations to these pathways.

Central and Endocrine Regulation of Metabolism: Implications for Female Reproduction

From single cells to complex organisms, maintenance of energy metabolism constitutes a fundamental homeostatic function required to sustain life. Importantly, complex organisms must also coordinate whole-body energy balance with that of cellular energetics. Therefore, the central nervous system and peripheral organs must be in constant communication to ensure energy supplies for cellular functions and protection against periods of energy scarcity.

In mammals, the hypothalamus, located in the basal part of the brain, plays a critical role in orchestrating whole-body energy homeostasis (Figure 2) (1). In the hypothalamus, a subset of neurons located in the arcuate nucleus that produce agouti-related peptide (Agrp) and neuropeptide-Y (NPY) (2–4) exerts a fundamental role in the promotion of feeding (5–7). The NPY/AgRP neurons are special in that their activity must be at the highest level when the whole body is lacking sufficient energy, such as during periods of food deprivation or fasting (8–12). Indeed, during negative energy balance, glucose levels are lower and NPY/AgRP neurons show increased firing (13).

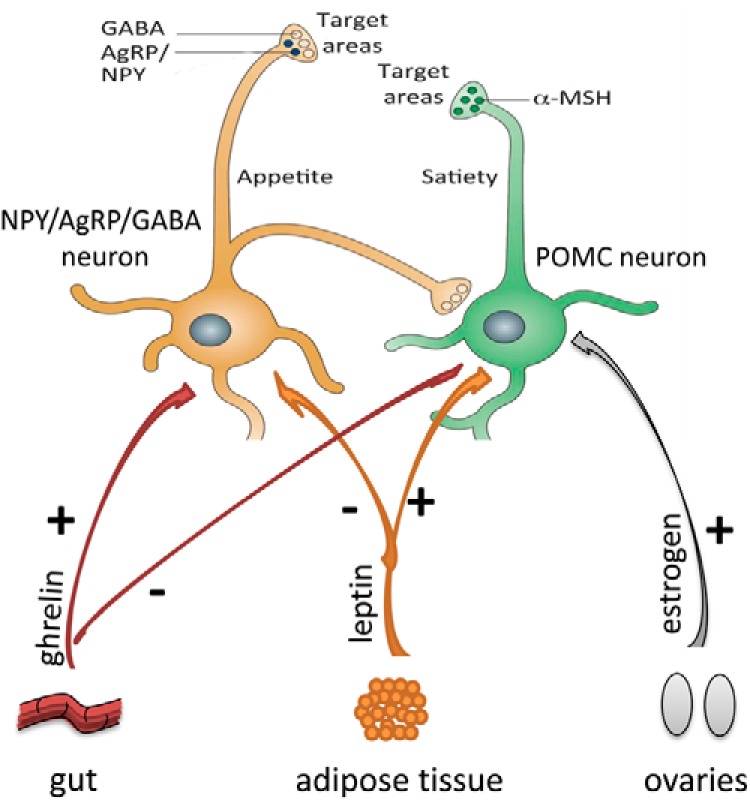

Figure 2.

Regulation of NPY/AgRP and POMC neuron activity via peripherally secreted hormones. Ghrelin secreted from gut during fasting increases firing of AgRP neurons and decreases action potential frequency of POMC neurons. Leptin secreted from adipose tissue increases activity of POMC neurons and diminishes activity of NPY/AgRP neurons. Estradiol increases excitatory input to POMC neurons. NPY/AgRP neurons also directly inhibit POMC perikarya.

Located near NPY/AgRP neurons, there is another population of cells that produce pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC neurons) and exert an opposite function (14, 15). Several studies have shown that POMC neurons increase their firing when glucose levels increase (16–18), consistent with the putative role of POMC cells as satiety signaling neurons (13). Activation of the POMC neurons (14, 19, 20) triggers the release of α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) from POMC axon terminals, which in turn activates melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R), leading to suppressed food intake (14) and increased energy expenditure. By contrast, promotion of the activity of NPY/AgRP neurons (14, 19–21) leads to release of AgRP, which antagonizes the effect of α-MSH on MC4R (4). The NPY/AgRP system not only antagonizes anorexigenic melanocortin cells at their target sites where MC4Rs are located, but also robustly and directly inhibits POMC perikarya (22–24). Such inhibition involves NPY as well as the small inhibitory AA neurotransmitter GABA (19, 22–25). This unidirectional (25, 26) interaction between the NPY/AgRP and POMC perikarya is significant because it provides tonic inhibition of the melanocortin cells whenever the NPY/AgRP neurons are active (23, 27). This anatomical organization might be the simplest explanation for why the baseline blueprint of feeding circuits is more likely to promote feeding rather than satiety. Although this bias toward a positive energy balance is a necessity from an evolutionary perspective, it is also a likely contributor to the etiology of metabolic disorders.

The activities of the orexigenic NPY/AgRP-producing neurons and the anorexigenic POMC/α-MSH-expressing neurons change in response to circulating glucose and free fatty acid levels that regulate AMP kinase (AMPK) activity and therefore conversion of AMP to ATP. In addition to circulating glucose and free fatty acids, the activities of NPY/AgRP and POMC neurons are also regulated by peripheral metabolic regulatory hormones including leptin, ghrelin, and insulin, which respond to the metabolic state of the organism. Leptin is a peptide hormone that is secreted primarily by the adipose tissue in proportion to adipose tissue mass and suppresses appetite (28). In the hypothalamus, leptin enhances firing of POMC cells via both pre- and postsynaptic modes of action (19), whereas the firing frequency of orexigenic NPY/AgRP neurons is diminished by leptin (29). By contrast, the gut-derived appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin is secreted in response to negative energy balance (eg fasting) and enhances the firing rate of NPY/AgRP neurons via a direct mechanism, whereas it decreases the action potential frequency of POMC cells predominantly by a presynaptic mode of action (30). The pancreas-derived hormone insulin was also shown to affect neuronal firing in the arcuate nucleus, an event that seems to be mediated by ATP-sensitive potassium channels (31).

The activities of NPY/AgRP and POMC neurons and metabolic hormones are required for the regulation of energy metabolism, as suggested by mouse knockout models (Table 1). The deficiency of POMC-derived peptides results in partially penetrant embryonic lethality. Moreover, these mice display obesity, defective adrenal development, and altered pigmentation (32). MC4R knockouts exhibit obesity, hyperphagia, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglycemia (33–36). Metabolic syndrome ensues in MC3R knockouts with increased adipose mass and decreased energy expenditure (37). There is an increased sensitivity to leptin and susceptibility to seizures in mice lacking NPY (38). Although early deletion of AgRP or both AgRP and NPY does not significantly alter energy metabolism, ablation of AgRP neurons in adult mice leads to significant AN and death (39–41). Mice homozygous for leptin mutation are obese and have high metabolic efficiency, impaired thermogenesis, short life span, and abnormalities in many organ systems including but not limited to cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, muscle, renal, and gastrointestinal systems (42). Similarly, mice deficient in leptin receptor are also obese, hyperinsulinemic, and hyperglycemic (43, 44). In contrast, ghrelin knockouts do not demonstrate phenotypical abnormalities on regular diet. However, they display increased utilization of fat as an energy substrate on a high-fat diet and enhanced glucose-induced insulin release (45, 46).

Table 1.

Knockout Phenotypes of Mice Lacking Key Molecules of Energy Metabolism

| Gene | General Phenotype | Reproductive Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| POMC | Obesity, defective adrenal development, and altered pigmentation (32) | Partially penetrant embryonic lethality (32) |

| NPY | Increased sensitivity to leptin and susceptibility to seizures (38) | Not reported |

| AgRP or AgRP/NPY | No significant alterations of energy metabolism in early deletion, significant AN, and death following ablation in adult mice (39–41) | Not reported |

| MC4R | Obesity, hyperphagia, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglycemia (33–36) | Not reported |

| MC3R | Increased adipose mass and decreased energy expenditure (37) | Not reported |

| Leptin/Leptin receptor | Obesity, high metabolic efficiency, hyperglycemia, impaired thermogenesis, infertility, short life span, and abnormalities in many organ systems (42–44) | Infertility, impaired folliculogenesis, follicle atresia (43, 44, 48) |

| Ghrelin | No phenotypic abnormalities on regular diet and increased utilization of fat as an energy substrate on a high fat diet (45, 46) | Not reported |

Although reproductive phenotype has not been reported for many of these knockouts, the probability that these models have abnormal reproduction is high considering that they have obesity, insulin resistance, and alterations of energy metabolism, abnormalities that are known to negatively affect reproduction in animal models and humans. Moreover, estradiol, a steroid hormone synthesized in female gonads, increases excitatory input to POMC neurons in wild-type rats and mice and is associated with decreased food intake and body weight gain, highlighting the importance of cross-talk between gonads and central hypothalamic neurons (47). A striking example of central metabolic deregulation and associated impaired reproduction is the leptin-knockout mice, characterized by female infertility and impaired folliculogenesis, associated with increased follicle atresia and granulosa cell apoptosis (48). AgRP neurons seem to play an important in the establishment of phenotype of leptin-deficient mice, as ablation of these neurons in moderately obese, adult Lepob/ob mice results in restoration of normal body weight and fertility (49, 50). Mice deficient in leptin receptor are also sterile (43, 44).

The Oocyte and Its Metabolism

To improve our understanding of the affect of central and endocrine metabolic regulation on female reproduction, it is necessary to delineate specific aspects of metabolic processes in the oocyte and early embryo.

Follicles in female gonads can be viewed as functional units that consist of oocytes and surrounding somatic granulosa and cumulus cells (Figure 3). Granulosa cells are somatic cells that surround the oocyte in early-stage (primordial, primary, secondary, early antral) follicles. In addition, in late-stage (late antral) follicles, they surround the follicular cavity as mural granulosa cells. Cumulus cells differentiate from granulosa cells in the final stages of follicle development and surround the oocyte in late-antral follicles. They are different from the mural granulosa cells in their function and gene expression pattern and are extruded from the follicle as part of the cumulus oophorus complex (COC) upon ovulation.

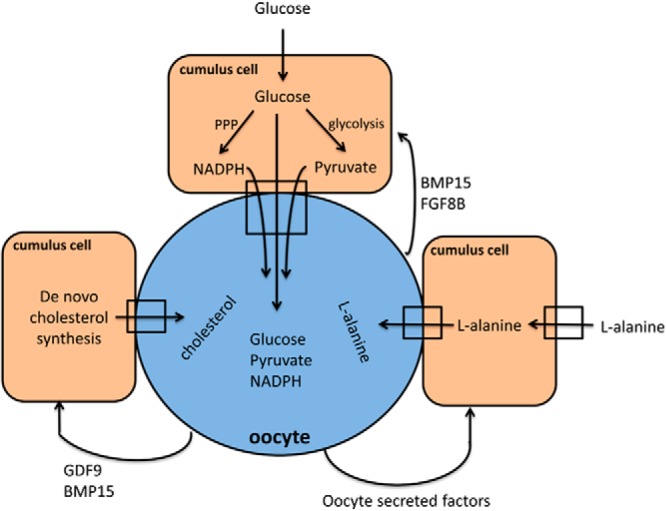

Figure 3.

Carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism in cumulus oocyte complexes. Glucose is taken up by cumulus cells and is converted to pyruvate via glycolysis, which then enters oocytes via gap junctions. Although glucose is also transported to the oocyte, its function is unknown and pyruvate is used as a major energy source. Cumulus cells also regulate redox status of oocytes by providing them with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, and transport de novo synthesized cholesterol and L-alanine taken from follicular fluid to the oocyte. Oocytes actively regulate these processes via secretion of growth factors.

During follicle development, oocyte and granulosa cells interact with each other to ensure the development of a competent oocyte, which can be fertilized and give rise to an embryo. Oocytes regulate the formation and activation of primordial follicles, follicle development (folliculogenesis), granulose-cell differentiation, and cumulus expansion. In return, granulosa cells provide nutritional support to the oocyte, regulate oocyte growth, maintain meiotic arrest, and play a role in suppression of transcription and induction of maturation (51, 52). To accomplish these complex tasks, granulosa cells and oocytes communicate with each other via juxtacrine and paracrine interactions (52, 53).

Interactions between the oocyte and the surrounding somatic cells that regulate oocyte metabolic function: gap junctions and paracrine interactions

Gap junctions are protein channels between two cells. They allow passage of small molecules (<1 kDa) and ions. Connexin proteins form a hemichannel on the surface of each cell and hemichannels on two adjacent cells connect to form a fully functional channel (54). Gap junctions exist between granulosa cells and oocytes, and also between adjacent granulosa cells (53). Gap junctions begin to form in primordial follicles during fetal development and expand as folliculogenesis proceeds postnatally (55, 56). The importance of gap junction communication between cells in follicles can be viewed in the context of animal knockout models of genes, which encode proteins comprising these channels. Loss of gap junctions between granulosa cells, as in the case of the connexin 43 (Cx43) knockouts, severely affects follicle development. Cx43 knockout follicles arrest at the early preantral stage of follicle development and produce incompetent oocytes (57). Connexin 37 (Cx37) is a protein that participates in the formation of gap junction channels on the surface of oocytes. Cx37 knockout ovaries demonstrate normal follicle development until the late-preantral stage; however, no late-antral (Graafian) follicle formation is observed. Moreover, follicle cells in these ovaries demonstrate early luteinization (58). It is not known which gap junctions on the surface of granulosa cells interact with Cx37 on oocytes, but Cx43 might be one of them. It is also worth noting that there are other connexin proteins, such as Cx32, Cx45, and Cx57, which are expressed in the ovaries but their functions have not yet been elucidated (53).

Paracrine interaction, which is mediated via secreted molecules, is another important form of communication between oocytes and granulosa cells. Although oocytes and granulosa cells are thought to secrete a myriad of factors, only few of them have been functionally characterized. Three major molecules secreted from oocytes and affecting follicle development are growth differentiation factor-9 (GDF9), bone morphogenetic protein 15 (BMP15), and fibroblast growth factor 8B (FGF8B). In mice, granulosa cells in the primary follicles of Gdf9 knockouts fail to proliferate and these animals are infertile; their follicles do not develop beyond the early preantral stage (59). Bmp15 knockout mice demonstrate female subfertility with ovulation and fertilization defects (60). A recent study demonstrated that BMP15:GDF9 heterodimers are much more active than their respective homodimers in mouse and human, indicating that these molecules act in concert to regulate ovarian functions (61). FGF8B is secreted by oocytes and regulates glycolysis in cumulus cells (52, 62). Deletion of Fgf8b along with three other relatively low-expressed fibroblast growth factor (FGF) variants leads to abnormal pregastrular embryo development with anteroposterior axis abnormalities (63). However, the specific effect of FGF8B on fertility remains to be further investigated. A paracrine factor produced from granulosa cells and affecting oocyte development is Kit ligand (51, 52). Mutations that decrease the expression of Kit ligand lead to infertility with arrest in follicular development (64, 65).

Importantly, the number of molecules that mediate paracrine interactions within the follicle is likely to be higher than identified so far. Two of the recently investigated paracrine regulatory molecules are endothelin-1, which is secreted from granulosa cells and plays a role in the induction of oocyte maturation following LH surge (66), and IL-7, which is produced by the oocytes and inhibits granulosa cell apoptosis (67). It is also noteworthy that paracrine interactions within the follicle do not occur exclusively between granulosa cells and oocytes. These interactions also medicate communication between granulosa and cumulus cells (68) (see below).

In addition to their role in oocyte metabolism (discussed below), gap junctions and paracrine interactions act synergistically to regulate oocyte maturation, a key event in oocyte development. From birth until sexual maturation, mammalian oocytes remain arrested at the prophase of the first meiotic division within the follicles. Meiotic arrest is mediated via high cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels within the oocytes; gap junctions and paracrine interactions mediate the inhibition of oocyte Phosphodiesterase 3A (PDE3A), which degrades cAMP (69). Mural granulosa cells of the follicles secrete natriuretic peptide precursor (NPPC), which interacts with NPPC receptor (NPR2) on cumulus cells, resulting in the synthesis of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in cumulus cells. cGMP is then transferred to the oocyte via gap junctions, inhibits PDE3A, and maintains meiotic arrest (68). However, following the LH surge, the production of NPCC in granulosa cells decreases, which leads to decreased cGMP production in cumulus cells (70). Moreover, gap junctions between the oocytes and surrounding cumulus cells are closed, further decreasing oocyte cGMP concentration. As a result, the inhibition of PDE3A is relieved, PDE3A degrades cAMP, and meiosis resumes (71). This mechanism operates both in mouse and human follicles and it seems that oocytes play an active role in this process via secretion of paracrine factors which increase cumulus cell expression of NPR2 and Inosine-5′-monophosohate dehydrogenase, the rate limiting enzyme in cGMP production (72). Although the regulation of oocytes' meiotic status is much more complex than described (73), this example of paracrine and gap junction interactions in the follicles demonstrate that they act in concert to ensure the development of competent oocytes.

Glucose, amino acid, and lipid metabolism in the oocyte

Glucose

Carbohydrate metabolism is the best-characterized metabolic process in oocytes and preimplantation embryos (Figure 3). Denuded oocytes cannot utilize glucose and fail to mature in media where glucose is the only source of energy. In contrast, oocytes in COCs undergo maturation in the presence of glucose as the sole nutrient (74). These findings suggest that oocytes are unable to utilize glucose unless cumulus cells are there to help the process. Interestingly, insulin receptors and molecules responsible for insulin signaling are present in both oocytes and cumulus cells. However, although oocytes have the machinery for insulin signaling, they do not respond to insulin, whereas both human and mouse cumulus cells are insulin responsive (75).

Unlike glucose, pyruvate can be utilized by denuded oocytes. In fact, Pdha1 knockout oocytes, where the enzyme responsible for pyruvate metabolism (pyruvate dehydrogenase) is defective, fail to complete meiotic maturation and exhibit meiotic spindle and chromatin abnormalities (76). Together these findings suggest that cumulus cells in COCs take up glucose from the circulation and convert it to pyruvate, which is then transported to the oocyte via gap junctions or cumulus cell secretion (52, 77).

Importantly, while the expression of genes encoding enzymes responsible for glycolysis is almost undetectable in oocytes, they demonstrate a strong expression pattern in cumulus cells. In addition, oocyte-secreted factors dramatically increase the expression of these genes. Therefore, oocytes ensure the supply of pyruvate from cumulus cells by inducing the expression of genes important in glycolysis (62). Oocytes also secrete factors that induce glycolysis in preantral granulosa cells (62). In contrast, tricarboxylic acid cycle-stimulating effects of oocyte-secreted molecules is observed in cumulus cells but not in preantral granulosa cells (62). BMP15 and FGFB8 are paracrine factors that regulate glycolysis in cumulus cells (78). Although each of these factors does not affect glycolysis significantly on its own, the combination of two has a dramatic effect (52).

Glucose metabolism via the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) in cumulus cells is equally important for oocyte metabolism. PPP provides the glycolytic pathway with intermediates; in fact, some authors believe that glycolysis in cumulus cells is defective and entirely dependent on PPP. Moreover, PPP regulates intracellular redox status of the oocyte via production of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (79).

Importnantly, glucose from cumulus cells can enter oocytes via gap junctions (80). However, the biological importance of glucose in the oocyte, where the expression of glycolytic enzymes is minimal, remains to be determined.

Amino acids

Amino acids are not mere building blocks of proteins: they are also actively used in other processes such as nucleotide and glutathione synthesis and the regulation of pH and osmolality. They can also serve as cellular energy sources (81). The reproductive tract is rich in amino acids, especially glutamine, glycine, and alanine (82, 83). Supplementation of in vitro maturation media with amino acids improves quality and developmental potential of oocytes. LH increases glutamine metabolism in bovine oocytes, and glutamine positively affects oocyte maturation (84, 85). Glutamine also increases oocyte quality and maturation in pig and mouse oocytes (86, 87). Glycine is another important amino acid for fully grown oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Glycine transporter GLYT1 is activated during oocyte maturation, transports glycine into the cell, and plays an important role in cell volume regulation (88, 89). Leucine uptake increases as follicles develop from preantral to antral stage (90). Glycine and cysteine transport increases at the time of oocyte maturation, which may suggest the need for glutathione (91). Overall, oocytes with high amino acid turnover seemingly have low developmental potential in comparison to oocytes with low amino acid turnover (92–94).

Importantly, gap junctions and paracrine interactions between the oocyte and the cumulus cells are also important for amino acid transport into the oocyte. Oocytes promote the expression of Slc38a3, an L-alanine transporter, in cumulus cells. Although oocytes themselves do not express this carrier, by promoting its expression in cumulus cells, they ensure L-alanine delivery into the oocyte via gap junctions. Although the increase in L-alanine uptake observed in cumulus cells is clearly via secretion of paracrine factors by the oocyte, none of the identified factors so far play a role in this process (52, 95).

Lipids

Intracellular lipids can be a potential endogenous energy source for the oocytes. Several lines of evidence show that lipids are important for oocyte maturation and early embryonic development, especially in farm animals (96). Inhibition of beta oxidation blocks meiotic resumption in mouse (97). Moreover, bovine and pig oocytes consume triglycerides (98, 99), and mouse oocytes up-regulate the expression of enzymes required for beta oxidation during maturation (100). However, the expression of genes required for cholesterol biosynthesis is minimal in oocytes. Therefore, oocytes are defective in their ability to synthesize cholesterol (101). Moreover, they lack the receptors of cholesterol uptake, high-density lipoprotein or low-density lipoprotein, and cannot take it up from follicular fluid either (102, 103). Cholesterol in the oocytes originates from cumulus cells. Studies show that cholesterol transported to the oocytes is mainly de novo synthesized, although cumulus cell uptake of follicular cholesterol with subsequent transfer to the oocyte is also possible (101). Oocytes induce the expression of genes required for cholesterol biosynthesis in cumulus cells and then cholesterol is transferred to the oocyte via gap junctions. Oocyte up-regulation of de novo cholesterol synthesis is via the paracrine and possibly juxtacrine communication. GDF-9 and BMP-15 are important paracrine factors affecting cumulus cell cholesterol metabolism (101).

Metabolism of the Preimplantation Embryo

Oxygen utilization is low in cleavage stage embryos, increases in blastocysts, and returns to preblastocyst levels following implantation (96, 104). This increase in oxygen consumption during blastocyst formation might be due to increased demand for ATP. ATP is required for protein synthesis and for ATP-dependent membrane pumps, which are necessary for blastocyst cavity formation (96, 105). Importantly, reactive oxygen species are generated as byproducts of oxygen metabolism and may have detrimental effects on embryos at high concentrations. Furthermore, reduction in oxygen concentration in embryo cultures was demonstrated to positively affect embryo development (106, 107).

Pyruvate seem to be the main energy source for cleavage stage embryos because they have poor glycolytic ability. Early-stage embryos transport pyruvate and lactate via monocarboxylate transporters on their membranes (108). Blastocysts, on the other hand, can efficiently metabolize glucose and convert it to lactate (109). Interestingly, blastocysts are insulin sensitive, with glucose transporter 8 (GLUT8) mediating insulin's effects on embryos (110). Other types of GLUT have also been identified in embryos such as GLUT1 and GLUT3. GLUT3 knockouts display embryonic lethality with increased apoptosis in blastocysts (111), and deficiency of GLUT1 results in fetal abnormalities (112). Too much glucose in systemic circulation, as is seen in diabetes, down-regulates GLUTs on embryonic cells, increases apoptosis in embryos, and leads to adverse fetal outcomes (108).

Amino acids (AAs) play similar roles in embryos when compared with oocytes. However, in addition to the aforementioned effects in oocytes, they have some extra functions in embryos. Embryos seem to consume glutamine and arginine and produce alanine consistently across species during preimplantation development (81, 113). Glutamine consumption dramatically increases at blastocyst stage, which improves embryo development in different species (114, 115). Histidine is secreted by human embryos and can serve as a signaling molecule through its conversion to histamine. This signaling function may be important in implantation (116). Nitric oxide is generated from Arginine and plays an important role in embryo development and establishment of pregnancy (117, 118). Alanine is important in pH regulation, and several additional AAs were demonstrated to be important in osmolarity regulation (119). AA uptake and secretion profiles show significant differences between fresh vs. cryopreserved, and in vitro vs. in vivo –grown embryos, highlighting the effects of assisted reproductive techniques on embryo metabolism (120, 121). Moreover, AA turnover in the culture media, perhaps in combination with other embryo assessment methods (morphology, genetics etc.,), may be an important indicator of embryo viability in in vitro fertilization (IVF) (81, 122, 123).

Although lipids are important endogenous energy sources for embryo development, little is known about lipid metabolism in embryos. Embryos that have small lipid stores, such as mice, are more dependent on nutrient provision in comparison to embryos with large lipid stores per volume unit, such as pig and sheep (96, 124). Most available data on lipids during embryo development is regarding their importance in postimplantation embryos and fetuses (125, 126). Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis is teratogenic and causes brain abnormalities in the developing rat offspring (127). Moreover, lipids are required for steroid synthesis and play important roles in brain development and signaling pathways, such as Wnt and Hedgehog (128, 129).

Effect of Calorie Restriction on Female Reproduction

Calorie restriction (CR) is the reduction of calorie intake. Calorie restriction with the maintenance of optimum nutrition was demonstrated to increase life span (average and maximum) and decrease age-related diseases in a number of species, including mammals (130, 131). Although positive effects of CR on aging are undisputable in rodents, convincing primate data are yet to be obtained (132). The most widely accepted theory on how CR leads to extended life span is that CR reduces the generation of reactive oxygen species that damage the mitochondria and are detrimental for the cell (130).

It is believed that an energy tradeoff exists between reproduction and life span. Energy investment in reproduction increases the chances of the conservation of the genetic material of the organism. Aging occurs as a side effect of this energy investment in reproduction instead of somatic maintenance. In other words, more energy could have been spent on somatic maintenance and this would have increased the fitness of the organism; however, in a natural environment where extrinsic forces such as predation and unfavorable climate changes were an important issue, this was not a selected trait (133, 134). In CR animals, more energy is allocated toward somatic maintenance and away from reproduction, because in the absence of adequate food in the environment, the survival of the offspring (because of the lack of energy sources) and the mother (because of the high energy demands of pregnancy and lactation) is unlikely. In fact, in mice and rats, CR decreases sperm counts and increases the number of abnormal sperm (135). Moreover, CR reduces fecundity in rodents and leads to anovulation in female mice (133, 136). Interestingly, however, follicular depletion rate decreases in these mice (136). This is also observed in the case of chemotherapy treatment of CR rats. CR protects ovaries from the damage of chemotherapeutic agents; CR rats have more primordial follicles in their ovaries following chemotherapy when compared with controls. It is thought that this effect is due to the reduced recruitment of primordial follicles and a decrease in oxidative stress, which is in line with the evidence that CR results in reduced fertility (137). These mechanisms provide a survival advantage for the species; in times of famine, by extending the reproductive life span, animals may postpone reproduction until they reach a more favorable environment.

How aging and reproduction are interlinked is yet to be determined, but effects of CR on hypothalamus and neuroendocrine system are worthy of investigation (134, 138). The abundance or lack of nutrients affects the neuroendocrine system, both in its prenatal development and postnatal function. For example, maternal nutrition affects the time of pubertal onset in female rats, where offspring of mothers who were fed with high-fat or CR diet exhibit early-pubertal onset (139). Moreover, postnatal CR delays sexual maturation in male rhesus monkeys (140). Some authors, however, argue that the existence of energy tradeoff between reproduction and life span is not entirely true because there are only minor differences in the gene expression in gonads of CR mice as detected by microarray. Furthermore, the genes that show differential expression are not involved in energy metabolism (141).

In humans, very little data are available on CR and its effect on reproduction. AN, an eating disorder that primarily affects women during adolescence and young adulthood with an estimated prevalence of 0.9% in United States (142) provides one model for CR in humans. It is a psychosomatic disorder where the perception of bodyweight and/or shape is disturbed and patients are extremely underweight (below minimal weight for age and height) with numerous medical and psychological complications (143, 144). AN has significant implications for reproduction. Most patients with AN report absence of menstruation at some point during the course of their illness; the hypothalamic origin of this amenorrhea is reflected in decreased blood concentrations of gonadotropins and estrogens and in the restoration of menses with GnRH injections (145–148). However, fertility rates of women with a history of AN are not different from the general population (149–152). Although some studies have reported no differences in pregnancy complications between women with AN history and general population (152), others have reported an increase in miscarriage and cesarean section rates (150) and a slight increase in antepartum hemorrhage rates (151). Mothers with AN consistently give birth to babies with lower birth weight compared with controls (143, 150–152). Although there are no data available on the menopausal age of women with a history of AN, it would be interesting to see whether they exhibit delayed menopause and whether there is a relationship between the duration of active AN and menopausal age, considering that CR decreases the rate of follicle depletion in animal models.

Effect of Calorie Excess, Obesity, and Diabetes on Female Reproduction

Although CR has important consequences for human reproduction, the effect of calorie excess is of greater concern in modern industrial societies. In the United States, for example, 55.8% of all women age 20–39 years are overweight or obese, according to National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2009 and 2010 (153). For many of these women, their elevated body mass indices are a result of excess caloric intake coupled with restricted activity levels. Excess body weight and caloric intake have negative effects on reproduction, as do the related metabolic conditions of diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (Table 2). It is worth noting that the interplay between caloric excess and reproductive function is not the exclusive domain of females. For instance, paternal body weight and caloric intake have been shown to correlate with reduced sperm quality (154) and impaired embryonic development in both mouse (155) and human (156). However, the focus of the remainder of this section will be on the effects of maternal metabolic disturbance and obesity on ovulation, conception, and early pregnancy.

Table 2.

Effect of Diabetes Mellitus, Caloric Excess, and Obesity on Female Reproduction

| State | Effects in Mouse Model | Effects in Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | Granulosa cells | |

| Increased apoptosis (151) | Increased rates of miscarriage (155) | |

| Decreased expression of connexin43 (151) | Increased rates of congenital anomalies in offspring (155) | |

| Oocytes | ||

| Decreased AMPK activity (152) | ||

| Decreased ATP (152) | ||

| Abnormal mitochondrial structure (153) | ||

| Decreased mitochondrial function (153) | ||

| Increased rates of aneuploidy (153) | ||

| Blastocyst | ||

| Increased apoptosis in inner cell mass (154) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | Oocytes | |

| Impaired chromatin remodeling (156) | Increased rates of anovulation (155) | |

| Decreased mitochondrial function (157) | Increased rates of miscarriage (155) | |

| Increased rates of apoptosis (157) | ||

| Decreased rates of fertilization (157) | Increased rates of congenital anomalies in offspring (155) | |

| Blastocyst | ||

| Increased apoptosis in inner cell mass (158) | ||

| Caloric excess | Granulosa cells | |

| Increased apoptosis (164–166) | Increased rates of ovulatory infertility (161–163) | |

| Oocytes | ||

| Decreased maturation (164–166) | ||

| Decreased mitochondrial function (164–166) | ||

| Increased rates of meiotic defects (167) | ||

| Decreased rates of fertilization (164–166) | ||

| Obesity | Granulosa cells | |

| Increased apoptosis (166) Oocytes Increased mitochondrial abnormalities (169) Increased rates of aneuploidy (166) |

Increased rates of anovulation (155) Decreased success at spontaneous conception (171) Decreased IVF success Fewer oocytes (172) More oocyte spindle defects (168) Increased rates of cycle cancellation (173) Decreased rates of clinical pregnancy and live birth (174) Increased risk of miscarriage (175–176) |

Diabetes is a clinically important example of the effect of excess metabolic substrate on reproductive function. Much as it does to other organs throughout the body, hyperglycemia has several deleterious effects on the ovary. The cumulus-oocyte complex has been studied in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes, in which streptozotocin was used to destroy pancreatic β cells and thereby induce hyperglycemia. In this model, the granulosa cells of the ovary have higher levels of apoptosis when compared with controls. In addition, diabetic mice have decreased expression of Cx43 in their cumulus-oocyte complexes, altering the metabolic exchange between cumulus cells and the oocyte (157). At the level of the oocyte, the hyperglycemia found in the streptozotocin mouse model results in both decreased levels of ATP and decreased AMPK activity. These metabolic disturbances correlate with delayed oocyte maturation, as measured by germinal vesicle breakdown. Pharmacologic AMPK activation with 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) partially restores oocyte maturation, suggesting that AMPK to some extent mediates this effect (158). Further work in the same mouse model revealed abnormal mitochondrial structure and function, wherein the tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolism was found to be less effective, underlying the decreased ATP levels in diabetic oocytes. These mitochondrial abnormalities also correlate with defects in spindle formation and chromosome organization during meiosis, which lead to increased rates of aneuploid oocytes (159). The metabolic dysfunction that begins in the diabetic oocyte continues in early embryonic development, where hyperglycemia induces decreased glucose uptake. This leads to apoptosis in the inner cell mass of the mouse blastocyst, a phenomenon that can be rescued by exogenous insulin administration and restoration of euglycemia (160).

Hyperinsulinemia, as seen in type 2 diabetes, also results in metabolic alterations with negative consequences on the oocyte and preimplantation embryo (161). Excess insulin in oocyte culture media has been shown to cause impaired chromatin remodeling in a murine model, mediated through phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase (162). Insulin-resistant mouse oocytes also have decreased mitochondrial function, increased rates of apoptosis, and decreased rates of fertilization (163). Furthermore, hyperinsulinemia can decrease embryonic glucose uptake, leading to inner-cell mass apoptosis. In a murine model, the increased apoptosis and decreased implantation of embryos cultured in the presence of high levels of IGF-I (164) can be rescued with metformin (165), similar to the benefits of metformin at reducing rates of first trimester miscarriage in patients with the insulin-resistant pathophysiology of PCOS (166).

Caloric excess caused by the quantity and type of dietary intake is another important metabolic cause of impaired fertility. Diets high in carbohydrates, especially those with high glycemic index, are associated with increased risk of ovulatory infertility (167), as are diets high in trans fatty acids (168) and animal protein (169). Although the diet high in glycemic content may mediate its reproductive effects directly as result of hyperglycemia or indirectly via altered insulin sensitivity and androgen levels, as in PCOS, the diet high in trans fatty acids likely impairs fertility via lipotoxicity (170). Free fatty acids are susceptible to oxidative damage; the resultant reactive oxygen species can disrupt the function of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria and lead to programmed cell death in a variety of cells, including the granulosa cells and oocytes. This process leads to increased follicular apoptosis, delayed oocyte maturation, and decreased fertilization rates in mice fed a high-fat diet (170–172). Further compounding these effects are meiotic defects and mitochondrial abnormalities in the oocytes of mice on a high-fat diet, similar to those seen in the diabetic mouse model, which likely add increased aneuploidy and early miscarriage to the reproductive obstacles created by a high-fat diet (173).

Obesity leads to adverse reproductive outcomes via many of the same pathways as diabetes and high-calorie/high-fat diets, with deleterious impacts on ovarian function and oocyte/embryo quality, plus several additional mechanisms, including endocrinologic perturbation and abnormal secretion of adipokines. Like in the diabetic and high fat diet mouse models, spindle defects are more common in oocytes obtained from failed IVF cycles from obese patients than from normal-weight controls (174). This once again correlates with increased rates of follicular cell apoptosis, oocyte aneuploidy, and mitochondrial abnormalities (172, 175). In addition, the follicular fluid of obese women has increased levels of insulin and lipids, which are associated with poor oocyte quality (176). The net effects of these problems manifest as subfertility when attempting to conceive spontaneously during ovulatory cycles (177); reduced success with IVF conception, with fewer oocytes collected (178), increased cycle cancellation rate (179), and decreased clinical pregnancy and live birth rates (180); and an increased miscarriage rate for obese and overweight women, as noted in meta-analyses of spontaneous and IVF pregnancies together (181) and spontaneous pregnancies alone (182). It does not seem that the miscarriage rate in overweight and obese women is secondary to impaired endometrial implantation, as a recent meta-analysis of outcomes for obese women using IVF with donor oocytes did not demonstrate any differences in rates of implantation, miscarriage, or live birth when compared with women of normal weight (183). Beyond the functional and qualitative changes within the oocyte in obese women, reproductive function is further hindered by several endocrinologic disturbances of obesity. Hyperinsulinemia of obesity is commonly seen in conjunction with hyperandrogenemia and PCOS, resulting in irregular menses and chronic anovulation (184). The decreased amplitude of LH pulses in obesity results in diminished luteal stimulation (185). Finally, as described earlier, the adipokine leptin is released from adipocytes and acts on the hypothalamus, by suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (186), and on the ovary, by inhibiting follicular growth (187).

With such varied mechanisms for reduced fertility in obese patients, and considering the decreased success of IVF in these women, some of the greatest hope for improved reproductive success lies in weight loss. Several small cohort studies have been carried out to investigate the benefits of exercise and dietary modification on fertility, some of which have been promising (188, 189). However, a Cochrane Review of the randomized controlled trials of lifestyle modifications for overweight and/or PCOS infertility patients did not reveal any data to support this simple intervention (190). A large, randomized controlled trial called the “LIFESTYLE study” has been begun in The Netherlands to better assess the clinical benefit of weight loss for these patients' reproductive health (191). Bariatric surgery has also drawn interest as a method of weight loss for improved fertility outcomes. The studies assessing its efficacy, however, are small, observational, and/or retrospective, so additional prospective studies will provide a better understanding of the fertility benefit to this approach (192–194).

Summary and Conclusions

Metabolism plays a crucial role in the physiology and pathophysiology of the female reproductive axis. The central regulation of mammalian metabolism relies upon hypothalamic neurons and peripheral hormones to communicate the overall metabolic status of the organism whereas the ovarian metabolic pathways utilize paracrine and juxtacrine interactions between the oocyte and follicular cells to achieve successful cellular metabolism. Because utilization of fuels in all tissues of the body are greatly regulated by the hypothalamic melanocortin system, additional research on the influence of these brain circuits on metabolic principles of the female reproductive axis under normal and impaired metabolic conditions is warranted. It will also be important to determine whether cell biological characteristics of various fuels unmasked recently in the melanocortin system (195–197) bears relevant shifts in fuel preference of tissues of the female reproductive system. With these new advances in hand, it may be that new avenues of medical interventions can be delivered to promote successful child bearing in diverse age groups.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01 HD59909 from National Institutes of Health/NICHD (to E.S.) and NIH Director's Pioneer Award DP1 DK098058 (to T.L.H.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- α-MSH

- α-melanocyte stimulating hormone

- AA

- amino acid

- Agrp

- agouti-related peptide

- AMPK

- adenosine 5′-monophosphate kinase

- AN

- anorexia nervosa

- BMP15

- bone morphogenetic protein 15

- cAMP

- cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- COC

- cumulus oophorus complex

- CR

- calorie restriction

- Cx

- connexin

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factor

- FGF8B

- fibroblast growth factor 8B

- GDF9

- growth differentiation factor-9

- GLUT

- glucose transporter

- IVF

- in vitro fertilization

- MC4R

- melanocortin receptor 4

- NPPC

- natriuretic peptide precursor

- NPR1

- NPPC receptor

- NPY

- neuropeptide-Y

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- PDE3A

- Phosphodiesterase 3A

- POMC

- pro-opiomelanocortin

- PPP

- pentose phosphate pathway.

References

- 1. Dietrich MO, Horvath TL. Feeding signals and brain circuitry. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30(9):1688–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Broberger C, Johansen J, Johansson C, Schalling M, Hökfelt T. The neuropeptide Y/agouti gene-related protein (AGRP) brain circuitry in normal, anorectic, and monosodium glutamate-treated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(25):15043–15048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horvath TL, Bechmann I, Naftolin F, Kalra SP, Leranth C. Heterogeneity in the neuropeptide Y-containing neurons of the rat arcuate nucleus: GABAergic and non-GABAergic subpopulations. Brain Res. 1997;756(1–2):283–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ollmann MM, Wilson BD, Yang YK, et al. Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science. 1997;278(5335):135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen HY, Trumbauer ME, Chen AS, et al. Orexigenic action of peripheral ghrelin is mediated by neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein. Endocrinology. 2004;145(6):2607–2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark JT, Kalra PS, Crowley WR, Kalra SP. Neuropeptide Y and human pancreatic polypeptide stimulate feeding behavior in rats. Endocrinology. 1984;115(1):427–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zarjevski N, Cusin I, Vettor R, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Jeanrenaud B. Chronic intracerebroventricular neuropeptide-Y administration to normal rats mimics hormonal and metabolic changes of obesity. Endocrinology. 1993;133(4):1753–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hahn TM, Breininger JF, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Coexpression of Agrp and NPY in fasting-activated hypothalamic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(4):271–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kohno D, Sone H, Minokoshi Y, Yada T. Ghrelin raises [Ca2+]i via AMPK in hypothalamic arcuate nucleus NPY neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366(2):388–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sternson SM, Shepherd GM, Friedman JM. Topographic mapping of VMH –> arcuate nucleus microcircuits and their reorganization by fasting. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(10):1356–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takahashi KA, Cone RD. Fasting induces a large, leptin-dependent increase in the intrinsic action potential frequency of orexigenic arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y/Agouti-related protein neurons. Endocrinology. 2005;146(3):1043–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang Y, Atasoy D, Su HH, Sternson SM. Hunger states switch a flip-flop memory circuit via a synaptic AMPK-dependent positive feedback loop. Cell. 2011;146(6):992–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fioramonti X, Contié S, Song Z, Routh VH, Lorsignol A, Penicaud L. Characterization of glucosensing neuron subpopulations in the arcuate nucleus: integration in neuropeptide Y and pro-opio melanocortin networks? Diabetes. 2007;56(5):1219–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aponte Y, Atasoy D, Sternson SM. AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(3):351–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cone RD. Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(5):571–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ibrahim N, Bosch MA, Smart JL, et al. Hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons are glucose responsive and express K(ATP) channels. Endocrinology. 2003;144(4):1331–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parton LE, Ye CP, Coppari R, et al. Glucose sensing by POMC neurons regulates glucose homeostasis and is impaired in obesity. Nature. 2007;449(7159):228–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang R, Liu X, Hentges ST, et al. The regulation of glucose-excited neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus by glucose and feeding-relevant peptides. Diabetes. 2004;53(8):1959–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, et al. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411(6836):480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elias CF, Aschkenasi C, Lee C, et al. Leptin differentially regulates NPY and POMC neurons projecting to the lateral hypothalamic area. Neuron. 1999;23(4):775–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krashes MJ, Koda S, Ye C, et al. Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J Clin InvestJ Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1424–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dietrich MO, Antunes C, Geliang G, et al. Agrp neurons mediate Sirt1's action on the melanocortin system and energy balance: roles for Sirt1 in neuronal firing and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2010;30(35):11815–11825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tong Q, Ye CP, Jones JE, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Synaptic release of GABA by AgRP neurons is required for normal regulation of energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(9):998–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu Q, Howell MP, Cowley MA, Palmiter RD. Starvation after AgRP neuron ablation is independent of melanocortin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(7):2687–2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Atasoy D, Betley JN, Su HH, Sternson SM. Deconstruction of a neural circuit for hunger. Nature. 2012;488(7410):172–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horvath TL, Naftolin F, Kalra SP, Leranth C. Neuropeptide-Y innervation of beta-endorphin-containing cells in the rat mediobasal hypothalamus: a light and electron microscopic double immunostaining analysis. Endocrinology. 1992;131(5):2461–2467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu Q, Howell MP, Palmiter RD. Ablation of neurons expressing agouti-related protein activates fos and gliosis in postsynaptic target regions. J Neurosci. 2008;28(37):9218–9226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, et al. Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science. 1995;269(5223):543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van den Top M, Lee K, Whyment AD, Blanks AM, Spanswick D. Orexigen-sensitive NPY/AgRP pacemaker neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(5):493–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cowley MA, Smith RG, Diano S, et al. The distribution and mechanism of action of ghrelin in the CNS demonstrates a novel hypothalamic circuit regulating energy homeostasis. Neuron. 2003;37(4):649–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spanswick D, Smith MA, Mirshamsi S, Routh VH, Ashford ML. Insulin activates ATP-sensitive K+ channels in hypothalamic neurons of lean, but not obese rats. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(8):757–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yaswen L, Diehl N, Brennan MB, Hochgeschwender U. Obesity in the mouse model of pro-opiomelanocortin deficiency responds to peripheral melanocortin. Nat Med. 1999;5(9):1066–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balthasar N, Dalgaard LT, Lee CE, et al. Divergence of melanocortin pathways in the control of food intake and energy expenditure. Cell. 2005;123(3):493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huszar D, Lynch CA, Fairchild-Huntress V, et al. Targeted disruption of the melanocortin-4 receptor results in obesity in mice. Cell. 1997;88(1):131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rossi J, Balthasar N, Olson D, et al. Melanocortin-4 receptors expressed by cholinergic neurons regulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011;13(2):195–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sutton GM, Trevaskis JL, Hulver MW, et al. Diet-genotype interactions in the development of the obese, insulin-resistant phenotype of C57BL/6J mice lacking melanocortin-3 or -4 receptors. Endocrinology. 2006;147(5):2183–2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Butler AA, Kesterson RA, Khong K, et al. A unique metabolic syndrome causes obesity in the melanocortin-3 receptor-deficient mouse. Endocrinology. 2000;141(9):3518–3521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Erickson JC, Clegg KE, Palmiter RD. Sensitivity to leptin and susceptibility to seizures of mice lacking neuropeptide Y. Nature. 1996;381(6581):415–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qian S, Chen H, Weingarth D, et al. Neither agouti-related protein nor neuropeptide Y is critically required for the regulation of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(14):5027–5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005;310(5748):683–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu Q, Boyle MP, Palmiter RD. Loss of GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons to the parabrachial nucleus leads to starvation. Cell. 2009;137(7):1225–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD. Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. Obes Res. 1996;4(1):101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen P, Zhao C, Cai X, et al. Selective deletion of leptin receptor in neurons leads to obesity. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(8):1113–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McMinn JE, Liu SM, Dragatsis I, et al. An allelic series for the leptin receptor gene generated by CRE and FLP recombinase. Mamm Genome. 2004;15(9):677–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dezaki K, Sone H, Koizumi M, et al. Blockade of pancreatic islet-derived ghrelin enhances insulin secretion to prevent high-fat diet-induced glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 2006;55(12):3486–3493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wortley KE, Anderson KD, Garcia K, et al. Genetic deletion of ghrelin does not decrease food intake but influences metabolic fuel preference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(21):8227–8232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gao Q, Mezei G, Nie Y, et al. Anorectic estrogen mimics leptin's effect on the rewiring of melanocortin cells and Stat3 signaling in obese animals. Nat Med. 2007;13(1):89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hamm ML, Bhat GK, Thompson WE, Mann DR. Folliculogenesis is impaired and granulosa cell apoptosis is increased in leptin-deficient mice. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(1):66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dietrich MO, Horvath TL. AgRP neurons: the foes of reproduction in leptin-deficient obese subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(8):2699–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu Q, Whiddon BB, Palmiter RD. Ablation of neurons expressing agouti-related protein, but not melanin concentrating hormone, in leptin-deficient mice restores metabolic functions and fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(8):3155–3160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kidder GM, Vanderhyden BC. Bidirectional communication between oocytes and follicle cells: ensuring oocyte developmental competence. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88(4):399–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Su YQ, Sugiura K, Eppig JJ. Mouse oocyte control of granulosa cell development and function: paracrine regulation of cumulus cell metabolism. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27(1):32–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kidder GM, Mhawi AA. Gap junctions and ovarian folliculogenesis. Reproduction. 2002;123(5):613–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bloemendal S, Kück U. Cell-to-cell communication in plants, animals, and fungi: a comparative review. Naturwissenschaften. 2013;100(1):3–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Eppig JJ. Intercommunication between mammalian oocytes and companion somatic cells. Bioessays. 1991;13(11):569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mitchell PA, Burghardt RC. The ontogeny of nexuses (gap junctions) in the ovary of the fetal mouse. Anat Rec. 1986;214(3):283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ackert CL, Gittens JE, O'Brien MJ, Eppig JJ, Kidder GM. Intercellular communication via connexin43 gap junctions is required for ovarian folliculogenesis in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2001;233(2):258–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Simon AM, Goodenough DA, Li E, Paul DL. Female infertility in mice lacking connexin 37. Nature. 1997;385(6616):525–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dong J, Albertini DF, Nishimori K, Kumar TR, Lu N, Matzuk MM. Growth differentiation factor-9 is required during early ovarian folliculogenesis. Nature. 1996;383(6600):531–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yan C, Wang P, DeMayo J, et al. Synergistic roles of bone morphogenetic protein 15 and growth differentiation factor 9 in ovarian function. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15(6):854–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Peng J, Li Q, Wigglesworth K, et al. Growth differentiation factor 9:bone morphogenetic protein 15 heterodimers are potent regulators of ovarian functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(8):E776–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sugiura K, Pendola FL, Eppig JJ. Oocyte control of metabolic cooperativity between oocytes and companion granulosa cells: energy metabolism. Dev Biol. 2005;279(1):20–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Guo Q, Li JY. Distinct functions of the major Fgf8 spliceform, Fgf8b, before and during mouse gastrulation. Development. 2007;134(12):2251–2260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huang EJ, Manova K, Packer AI, Sanchez S, Bachvarova RF, Besmer P. The murine steel panda mutation affects kit ligand expression and growth of early ovarian follicles. Dev Biol. 1993;157(1):100–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kuroda H, Terada N, Nakayama H, Matsumoto K, Kitamura Y. Infertility due to growth arrest of ovarian follicles in Sl/Slt mice. Dev Biol. 1988;126(1):71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kawamura K, Ye Y, Liang CG, et al. Paracrine regulation of the resumption of oocyte meiosis by endothelin-1. Dev Biol. 2009;327(1):62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cheng Y, Yata A, Klein C, Cho JH, Deguchi M, Hsueh AJ. Oocyte-expressed interleukin 7 suppresses granulosa cell apoptosis and promotes oocyte maturation in rats. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(4):707–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhang M, Su YQ, Sugiura K, Xia G, Eppig JJ. Granulosa cell ligand NPPC and its receptor NPR2 maintain meiotic arrest in mouse oocytes. Science. 2010;330(6002):366–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu L, Kong N, Xia G, Zhang M. Molecular control of oocyte meiotic arrest and resumption. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2013;25(3):463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Kawamura N, et al. Pre-ovulatory LH/hCG surge decreases C-type natriuretic peptide secretion by ovarian granulosa cells to promote meiotic resumption of pre-ovulatory oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(11):3094–3101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang M, Xia G. Hormonal control of mammalian oocyte meiosis at diplotene stage. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(8):1279–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wigglesworth K, Lee KB, O'Brien MJ, Peng J, Matzuk MM, Eppig JJ. Bidirectional communication between oocytes and ovarian follicular somatic cells is required for meiotic arrest of mammalian oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(39):E3723–3729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sun QY, Miao YL, Schatten H. Towards a new understanding on the regulation of mammalian oocyte meiosis resumption. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(17):2741–2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Biggers JD, Whittingham DG, Donahue RP. The pattern of energy metabolism in the mouse oöcyte and zygote. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;58(2):560–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Purcell SH, Chi MM, Lanzendorf S, Moley KH. Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake occurs in specialized cells within the cumulus oocyte complex. Endocrinology. 2012;153(5):2444–2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Johnson MT, Freeman EA, Gardner DK, Hunt PA. Oxidative metabolism of pyruvate is required for meiotic maturation of murine oocytes in vivo. Biol Reprod. 2007;77(1):2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sutton-McDowall ML, Gilchrist RB, Thompson JG. The pivotal role of glucose metabolism in determining oocyte developmental competence. Reproduction. 2010;139(4):685–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sugiura K, Su YQ, Diaz FJ, et al. Oocyte-derived BMP15 and FGFs cooperate to promote glycolysis in cumulus cells. Development. 2007;134(14):2593–2603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Li Q, Miao DQ, Zhou P, et al. Glucose metabolism in mouse cumulus cells prevents oocyte aging by maintaining both energy supply and the intracellular redox potential. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(6):1111–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wang Q, Chi MM, Schedl T, Moley KH. An intercellular pathway for glucose transport into mouse oocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302(12):E1511–1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sturmey RG, Brison DR, Leese HJ. Symposium: innovative techniques in human embryo viability assessment. Assessing embryo viability by measurement of amino acid turnover. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17(4):486–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Harris SE, Gopichandran N, Picton HM, Leese HJ, Orsi NM. Nutrient concentrations in murine follicular fluid and the female reproductive tract. Theriogenology. 2005;64(4):992–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hugentobler SA, Diskin MG, Leese HJ, et al. Amino acids in oviduct and uterine fluid and blood plasma during the estrous cycle in the bovine. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74(4):445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Bilodeau-Goeseels S. Effects of culture media and energy sources on the inhibition of nuclear maturation in bovine oocytes. Theriogenology. 2006;66(2):297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zuelke KA, Brackett BG. Increased glutamine metabolism in bovine cumulus cell-enclosed and denuded oocytes after in vitro maturation with luteinizing hormone. Biol Reprod. 1993;48(4):815–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Downs SM, Hudson ED. Energy substrates and the completion of spontaneous meiotic maturation. Zygote. 2000;8(4):339–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hong J, Lee E. Intrafollicular amino acid concentration and the effect of amino acids in a defined maturation medium on porcine oocyte maturation, fertilization, and preimplantation development. Theriogenology. 2007;68(5):728–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Baltz JM, Tartia AP. Cell volume regulation in oocytes and early embryos: connecting physiology to successful culture media. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(2):166–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Baltz JM, Zhou C. Cell volume regulation in mammalian oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2012;79(12):821–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chand AL, Legge M. Amino acid transport system L activity in developing mouse ovarian follicles. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(11):3102–3108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pelland AM, Corbett HE, Baltz JM. Amino Acid transport mechanisms in mouse oocytes during growth and meiotic maturation. Biol Reprod. 2009;81(6):1041–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Collado-Fernandez E, Picton HM, Dumollard R. Metabolism throughout follicle and oocyte development in mammals. Int J Dev Biol. 2012;56(10–12):799–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hemmings KE, Leese HJ, Picton HM. Amino acid turnover by bovine oocytes provides an index of oocyte developmental competence in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(5):165, 161–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hemmings KE, Maruthini D, Vyjayanthi S, et al. Amino acid turnover by human oocytes is influenced by gamete developmental competence, patient characteristics and gonadotrophin treatment. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(4):1031–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Eppig JJ, Pendola FL, Wigglesworth K, Pendola JK. Mouse oocytes regulate metabolic cooperativity between granulosa cells and oocytes: amino acid transport. Biol Reprod. 2005;73(2):351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Leese HJ. Metabolism of the preimplantation embryo: 40 years on. Reproduction. 2012;143(4):417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Downs SM, Mosey JL, Klinger J. Fatty acid oxidation and meiotic resumption in mouse oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76(9):844–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ferguson EM, Leese HJ. Triglyceride content of bovine oocytes and early embryos. J Reprod Fertil. 1999;116(2):373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sturmey RG, Leese HJ. Energy metabolism in pig oocytes and early embryos. Reproduction. 2003;126(2):197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Dunning KR, Cashman K, Russell DL, Thompson JG, Norman RJ, Robker RL. Beta-oxidation is essential for mouse oocyte developmental competence and early embryo development. Biol Reprod. 2010;83(6):909–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Su YQ, Sugiura K, Wigglesworth K, et al. Oocyte regulation of metabolic cooperativity between mouse cumulus cells and oocytes: BMP15 and GDF9 control cholesterol biosynthesis in cumulus cells. Development. 2008;135(1):111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Sato N, Kawamura K, Fukuda J, et al. Expression of LDL receptor and uptake of LDL in mouse preimplantation embryos. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202(1–2):191–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Trigatti B, Rayburn H, Viñals M, et al. Influence of the high density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI on reproductive and cardiovascular pathophysiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(16):9322–9327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Houghton FD, Thompson JG, Kennedy CJ, Leese HJ. Oxygen consumption and energy metabolism of the early mouse embryo. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;44(4):476–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Houghton FD, Humpherson PG, Hawkhead JA, Hall CJ, Leese HJ. Na+, K+, ATPase activity in the human and bovine preimplantation embryo. Dev Biol. 2003;263(2):360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Fischer B, Bavister BD. Oxygen tension in the oviduct and uterus of rhesus monkeys, hamsters and rabbits. J Reprod Fertil. 1993;99(2):673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Orsi NM, Leese HJ. Protection against reactive oxygen species during mouse preimplantation embryo development: role of EDTA, oxygen tension, catalase, superoxide dismutase and pyruvate. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;59(1):44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Purcell SH, Moley KH. Glucose transporters in gametes and preimplantation embryos. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(10):483–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Leese HJ. Metabolic control during preimplantation mammalian development. Hum Reprod Update. 1995;1(1):63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Carayannopoulos MO, Chi MM, Cui Y, et al. GLUT8 is a glucose transporter responsible for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in the blastocyst. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(13):7313–7318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ganguly A, McKnight RA, Raychaudhuri S, et al. Glucose transporter isoform-3 mutations cause early pregnancy loss and fetal growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(5):E1241–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Heilig CW, Saunders T, Brosius FC, 3rd, et al. Glucose transporter-1-deficient mice exhibit impaired development and deformities that are similar to diabetic embryopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(26):15613–15618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Donnay I, Partridge RJ, Leese HJ. Can embryo metabolism be used for selecting bovine embryos before transfer? Reprod Nutr Dev. 1999;39(5–6):523–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Carney EW, Bavister BD. Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of amino acids on the development of hamster eight-cell embryos in vitro. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1987;4(3):162–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Chatot CL, Ziomek CA, Bavister BD, Lewis JL, Torres I. An improved culture medium supports development of random-bred 1-cell mouse embryos in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1989;86(2):679–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Wood GW, Hausmann EH, Choudhuri R, Dileepan KN. Expression and regulation of histidine decarboxylase mRNA expression in the uterus during pregnancy in the mouse. Cytokine. 2000;12(6):622–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Kim BH, Kim CH, Jung KY, Jeon BH, Ju EJ, Choo YK. Involvement of nitric oxide during in vitro fertilization and early embryonic development in mice. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27(1):86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sengupta J, Dhawan L, Lalitkumar PG, Ghosh D. Nitric oxide in blastocyst implantation in the rhesus monkey. Reproduction. 2005;130(3):321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Miyoshi K, Abeydeera LR, Okuda K, Niwa K. Effects of osmolarity and amino acids in a chemically defined medium on development of rat one-cell embryos. J Reprod Fertil. 1995;103(1):27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Jung YG, Sakata T, Lee ES, Fukui Y. Amino acid metabolism of bovine blastocysts derived from parthenogenetically activated or in vitro fertilized oocytes. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1998;10(3):279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Partridge RJ, Leese HJ. Consumption of amino acids by bovine preimplantation embryos. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1996;8(6):945–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Houghton FD, Hawkhead JA, Humpherson PG, et al. Non-invasive amino acid turnover predicts human embryo developmental capacity. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(4):999–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Brison DR, Houghton FD, Falconer D, et al. Identification of viable embryos in IVF by non-invasive measurement of amino acid turnover. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(10):2319–2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Sturmey RG, Reis A, Leese HJ, McEvoy TG. Role of fatty acids in energy provision during oocyte maturation and early embryo development. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44 Suppl 3:50–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Herz J, Farese RV., Jr The LDL receptor gene family, apolipoprotein B and cholesterol in embryonic development. J Nutr. 1999;129(2S Suppl):473S–475S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Woollett LA. Where does fetal and embryonic cholesterol originate and what does it do? Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:97–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Roux C, Wolf C, Mulliez N, et al. Role of cholesterol in embryonic development. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5 Suppl):1270S–1279S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Farese RV, Jr., Herz J. Cholesterol metabolism and embryogenesis. Trends Genet. 1998;14(3):115–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Willnow TE, Hammes A, Eaton S. Lipoproteins and their receptors in embryonic development: more than cholesterol clearance. Development. 2007;134(18):3239–3249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Anderson RM, Weindruch R. Metabolic reprogramming, caloric restriction and aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(3):134–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Omodei D, Fontana L. Calorie restriction and prevention of age-associated chronic disease. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(11):1537–1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Marchal J, Perret M, Aujard F. [Caloric restriction in primates: how efficient as an anti-aging approach?]. Med Sci (Paris). 2012;28(12):1081–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Holliday R. Aging is no longer an unsolved problem in biology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Nalam RL, Pletcher SD, Matzuk MM. Appetite for reproduction: dietary restriction, aging and the mammalian gonad. J Biol. 2008;7(7):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Brinkworth MH, Anderson D, McLean AE. Effects of dietary imbalances on spermatogenesis in CD-1 mice and CD rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 1992;30(1):29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Nelson JF, Gosden RG, Felicio LS. Effect of dietary restriction on estrous cyclicity and follicular reserves in aging C57BL/6J mice. Biol Reprod. 1985;32(3):515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Xiang Y, Xu J, Li L, et al. Calorie restriction increases primordial follicle reserve in mature female chemotherapy-treated rats. Gene. 2012;493(1):77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Shin BC, Dai Y, Thamotharan M, Gibson LC, Devaskar SU. Pre- and postnatal calorie restriction perturbs early hypothalamic neuropeptide and energy balance. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90(6):1169–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Sloboda DM, Howie GJ, Pleasants A, Gluckman PD, Vickers MH. Pre- and postnatal nutritional histories influence reproductive maturation and ovarian function in the rat. PloS One. 2009;4(8):e6744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Mattison JA, Lane MA, Roth GS, Ingram DK. Calorie restriction in rhesus monkeys. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38(1–2):35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Sharov AA, Falco G, Piao Y, et al. Effects of aging and calorie restriction on the global gene expression profiles of mouse testis and ovary. BMC Biol. 2008;6:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr., Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Hoffman ER, Zerwas SC, Bulik CM. Reproductive issues in anorexia nervosa. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;6(4):403–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Katz MG, Vollenhoven B. The reproductive endocrine consequences of anorexia nervosa. BJOG. 2000;107(6):707–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Braat DD, Schoemaker R, Schoemaker J. Life table analysis of fecundity in intravenously gonadotropin-releasing hormone-treated patients with normogonadotropic and hypogonadotropic amenorrhea. Fertil Steril. 1991;55(2):266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Carpenter SE. Psychosocial menstrual disorders: stress, exercise and diet's effect on the menstrual cycle. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;6(6):536–539 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Reid RL, Van Vugt DA. Weight-related changes in reproduction function. Fertil Steril. 1987;48(6):905–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]