Abstract

Pharmacotherapy based on 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) is a preferred treatment for ulcerative colitis, but variable patient response to this therapy is observed. Inflammation can affect therapeutic outcomes by regulating the expression and activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes; its effect on 5-ASA metabolism by the colonic arylamine N-acetyltransferase (NAT) enzyme isoforms is not firmly established. We examined if inflammation affects the capacity for colonic 5-ASA metabolism and NAT enzyme expression. 5-ASA metabolism by colonic mucosal homogenates was directly measured with a novel fluorimetric rate assay. 5-ASA metabolism reported by the assay was dependent on Ac-CoA, inhibited by alternative NAT substrates (isoniazid, p-aminobenzoylglutamate), and saturable with Km (5-ASA) = 5.8 μM. A mouse model of acute dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) colitis caused pronounced inflammation in central and distal colon, and modest inflammation of proximal colon, defined by myeloperoxidase activity and histology. DSS colitis reduced capacity for 5-ASA metabolism in central and distal colon segments by 52 and 51%, respectively. Use of selective substrates of NAT isoforms to inhibit 5-ASA metabolism suggested that mNAT2 mediated 5-ASA metabolism in normal and colitis conditions. Western blot and real-time RT-PCR identified that proximal and distal mucosa had a decreased mNAT2 protein-to-mRNA ratio after DSS. In conclusion, an acute colonic inflammation impairs the expression and function of mNAT2 enzyme, thereby diminishing the capacity for 5-ASA metabolism by colonic mucosa.

Keywords: drug metabolism, fluorescence, dextran sulfate sodium, myeloperoxidase, kinetics, enzymatic assay, inflammatory bowel disease, enzyme isoform

the two major inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease, afflict 1.4 million individuals in the United States (USA) and 2.2 million in Europe (42). To induce and maintain mucosal healing of the colonic mucosa, the major goal of UC therapy is to reduce or eliminate colonic inflammation. For mild to moderate inflammation, therapy based on the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory compound 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) is frequently prescribed. In information compiled by the National Institutes of Health from the 2004 Verispan database of prescriptions filled at retail pharmacies in the USA, 5-ASA or its prodrugs accounted for 44% of Crohn's disease prescriptions and 81% of UC prescriptions (23). It is not well understood how 5-ASA induces its anti-inflammatory effect on colonic mucosa, but multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including inhibition of intestinal macrophage chemotaxis (47), inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine release (25), inhibition of cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin pathways (28), inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activation (20), agonist of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (55), upregulation of the heat shock protein (heme oxygenase-1 enzyme) expression and activity (9, 22, 33), and antioxidative and free radical scavenger action (3, 53, 58). Although 5-ASA therapy is well tolerated and effective in patients with mild to moderate inflammation, many patients are refractory to this therapy or undergo relapse when 5-ASA is used to maintain remission (24). For this reason, and because of the undesirability of long-term corticosteroid use as the next level of UC therapy (46), there is strong interest in understanding the basis for variable outcomes with 5-ASA.

A long-standing hypothesis is that variable therapeutic outcomes are the result of variable 5-ASA metabolism among patients. After 5-ASA administration, the N-acetylation of 5-ASA produces the major metabolite (Ac-5-ASA), which can be detected in colonic tissue, colonic lumen, plasma, and urine along with minor metabolites (2, 19, 60). 5-ASA is known to act locally in the intestinal mucosa, since its efficacy is more closely correlated to drug mucosal concentration rather than blood concentration (17). This has focused attention on 5-ASA metabolism by N-acetyltransferase (NAT) enzymes in colonic mucosa.

Arylamine N-acetyltransferases are phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes that catalyze the transfer of an acetyl moiety from acetyl-coenzyme A (Ac-CoA), or another acetyl donor, to the nitrogen (N-acetylation) or oxygen atom of numerous aromatic and heterocyclic amine drugs such as the antihypertensive hydralazine, antitubercular isoniazid, and antibacterial sulfonamides (23, 30, 52). NATs have been identified in numerous species, including humans (7) and mice (39) where two functional NAT isoforms have been described. Human NAT-1 (hNAT1) is the ortholog of mouse NAT-2 (mNAT2); and human NAT-2 (hNAT2) is the ortholog of mouse NAT-1 (mNAT1) (57). A third NAT has also been identified. In humans, it is a pseudogene (NATP) (7) and in mice an expressed but relatively inactive mNAT3 isoform (22). There is functional homology between the human and mouse orthologs of isoforms 1 and 2 at the level of tissue distribution, developmental expression, substrate specificity, sequence similarity, and molecular structure (57). The hNAT1/mNAT2 isoform is expressed in a wide range of tissues, including liver, colon, small intestine, placenta, lungs, kidney, bladder, blood, and skin (11, 18, 32, 59). In contrast, hNAT2/mNAT1 is expressed mainly in liver, small intestine, and colon (13, 14, 29, 32, 35).

It remains an open question how 5-ASA metabolism affects drug efficacy against colitis. It has been difficult to link the outcomes of 5-ASA therapy to NAT gene polymorphisms that produce rapid or slow acetylation (27, 31, 54) because the human and mouse colon express both NAT isoforms (11, 18, 32, 64), and 5-ASA is a substrate for both NAT isoforms (22, 38). It also remains unclear whether 5-ASA or its metabolite is an active moiety of therapy. In both cell-free and intact-cell assays, 5-ASA is more potent as an antioxidant than Ac-5-ASA (1, 4, 26, 58), but the two compounds have been reported to have similar potency at inhibiting lipoxygenase (5), eicosanoid production (21), interferon-γ action (13, 14), lipid peroxidation (67), and scavenging HOCl (63). While topical application of Ac-5-ASA to the colon may be of limited or no therapeutic value (61, 66), negative findings may be explained by the slow uptake of Ac-5-ASA vs. 5-ASA by colonocytes (37). Conceptually, unless both 5-ASA and Ac-5-ASA are equally effective as anti-inflammatory drugs, changes in NAT activity are predicted to change the efficacy of 5-ASA therapy.

Inflammation is known to change activity of many enzymes and transporters that affect therapeutic drugs (8, 45, 51, 62, 65); therefore, for drug efficacy, it is important to know if this central feature of IBD is by itself affecting 5-ASA metabolism. Unfortunately, this has only been examined in small studies using IBD patients with diverse clinical status, and results are conflicting. It has been reported that IBD patients with active disease have a lowered plasma Ac-5-ASA-to-5-ASA ratio vs. healthy controls (19), but this conflicts with observations of others who saw no change in 5-ASA acetylation rates in colonic biopsy homogenates or isolated colonocytes from IBD patients (2, 36, 41). At present, we cannot firmly predict if decreased 5-ASA metabolism is a reproducible finding in inflamed tissue or if such a change in metabolism would improve or reduce the clinical benefit of 5-ASA therapy. In this study, we approach the first aspect of this uncertainty by validating a fluorimetric assay to directly measure Ac-5-ASA production and then use a murine acute colitis model to test if inflammation modulates colonic 5-ASA metabolic capacity and regulates expression of colonic NAT enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed and bred in facilities with controlled room temperature (70 ± 2°F), 30–70% humidity, and 14:10-h light-dark cycles. Mice were fed with standard pellet diet and tap water ad libitum. All experiments and protocols for animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Cincinnati.

Dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis.

Twelve-week-old mice received 2.5% wt/vol dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) (molecular weight 36–50 kDa; MP Biomedical, Solon, OH) dissolved in water for 5 days, then switched to regular drinking water for a subsequent 2 days, and killed. Age-matched control mice received regular water.

Colon tissue preparation.

After animal death, the entire colon was removed and placed immediately in ice-cold PBS (pH = 7.4), and then colon length was measured. Luminal contents were flushed out with cold PBS, and the gut was slit open longitudinally on the antimesenteric side. For the colitis study, the entire length of colon was then divided in half longitudinally, with one half used for histology and the other half used for biochemical analyses. For each use, colon tissue was divided into the following three sections: the area including all macroscopically visible rugae was designated as proximal colon; the remaining tissue was divided in two equal sections designated as central and distal colon (see Fig. 5A).

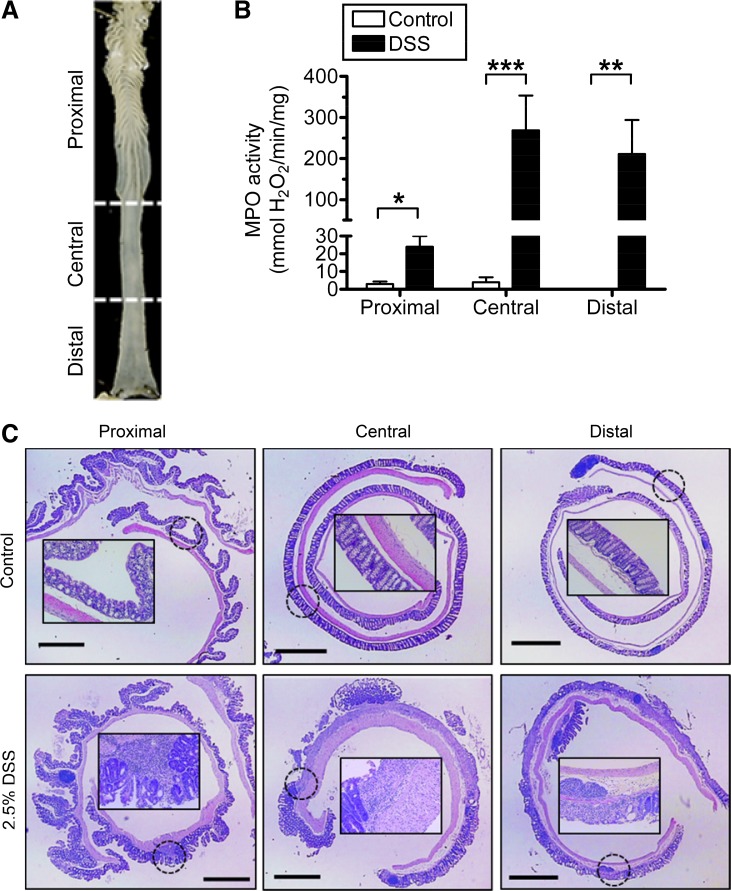

Fig. 5.

Segmental evaluation of granulocyte infiltration and histopathology after DSS. A: excised mouse colon, with markings and text to indicate the three colon sections used to evaluate longitudinal heterogeneity of colitis and 5-ASA metabolism. B: myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in mucosal homogenates from different colon segments. Control mice (white bars) were given normal drinking water. Acute colitis (black bars) was induced by addition of 2.5% DSS to drinking water for 5 days as described in materials and methods. Values are means ± SE for n = 6 (control) or n = 9 (DSS) mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 comparing DSS treatment vs. corresponding colon segment control. C: representative images of each colon section stained with hematoxylin and eosin showing histological alterations after colitis protocol; original magnifications ×20. The inset (×200) magnifies the general area indicated by the dotted circle. Bar = 1 mm.

Histology.

Full-thickness colonic tissue was staged as a Swiss roll (44), fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, transferred to 70% ethanol, and embedded in Paraplast (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Tissue sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and subjected to blinded evaluation by a pathologist.

Homogenate for biochemical analyses.

Colonic tissue was muscle stripped. Resultant mucosal sheets (in some cases divided into proximal, central, and distal sections as described) were homogenized in 300–500 μl of ice-cold Sorensen's sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 7.0) with 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors (mini Complete; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). An aliquot of homogenate was prepared for myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity measurement as described below, remaining homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 3 min at 4°C, and supernatants were separated into aliquots and stored at −80°C until use.

MPO activity.

MPO activity in colon mucosal homogenates was determined colorimetrically (40). Mucosa homogenate was mixed with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 6) and a final concentration of 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Homogenates were sonicated on ice for 15 s, subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles (liquid nitrogen-37°C water bath), and then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. MPO activity of supernatant was assayed at room temperature in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 6) containing 0.5 mM o-dianisidine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.0005% H2O2 (Fisher Scientific). Absorbance at 450 nm was recorded for the initial 2 min of the enzymatic reaction. MPO specific activity was calculated from rates of absorbance change, normalized to protein amount (bicinchoninc acid method; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), and assuming a molar extinction coefficient of 1.13 × 10−2/μmol·cm of oxidized o-dianisidine.

Assay of 5-ASA metabolism by NAT.

For routine assay, colon mucosal homogenate was diluted to 0.25–0.50 mg/ml in Sorensen's sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 7.0) and mixed with the NAT cofactor Ac-CoA (0.420 mM; Sigma-Aldrich). After equilibration 5 min at 30°C, 5-ASA (25 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to start the reaction. Rate of Ac-5-ASA production was measured for the initial 2 min of the enzymatic reaction in a fluorometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) at 312 nm excitation and 437 nm emission. NAT activity was calculated by reference to a standard curve of Ac-5-ASA fluorescence (0.010–1 μM; Pharmacia, Kalamazoo, MI) and normalized to sample protein.

Some experiments varied Ac-CoA (0–0.420 mM) or 5-ASA (0–50 μM). Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters were calculated by nonlinear regression curve fitting (Prism 4; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). In some experiments, reactions additionally contained isoniazid (0.01–10 mM) or p-aminobenzoylglutamate (p-ABG, 0.01–3 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich). Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were calculated by nonlinear regression curve fitting to a one-site competition binding equation (Prism 4). In some experiments testing enzyme stability, homogenates were frozen and thawed multiple times, before analysis.

Measurement of mNAT2 protein.

Colon mucosal homogenates were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were incubated with a blocking buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and then probed with rabbit antisera specific for mNAT2 protein (antiserum 195; Dr. E. Sim, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK) at 1:10,000 dilution (12) and Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-rabbit (1:5,000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Loading control was β-actin [primary antibody 1:20,000 mouse monoclonal (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), secondary antisera 1:10,000 Alexa Fluor 800 goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen)]. Blots were imaged and bands were quantified by an Odyssey Infrared Imager (Li-Cor Biosciences). Background-subtracted mNAT2 integrated intensity was normalized to β-actin to control for protein loading and then normalized vs. an internal control (liver homogenate) present in each gel to allow comparison between membranes.

Cytosolic and membrane protein fractions of colon mucosa homogenate from a distal section were created by a BioVision kit (Mountain View, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of mNAT2 mRNA.

Muscle-stripped colonic mucosa was collected before tissue homogenization. Total RNA was extracted (TRI Reagent; Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and then reverse transcribed (iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit; Bio-Rad). cDNA was amplified by real-time PCR using primers for mnat2 (41) and gapdh using a Fast SYBR Green Master Mix kit (AB Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a thermal cycler (StepOne Real-Time PCR System, with StepOne Software version 2.1; AB Applied BioSystems). Raw cycle threshold values (Ct values) obtained from mnat target samples were deducted from the Ct value obtained from internal control (gapdh) amplification and calculated relative to a positive control (liver), using the ΔΔCt method as follows: ΔΔCt = (Ct target − Ct target GAPDH) − (Ct liver − Ct liver GAPDH). Final relative values of mRNA abundance were calculated as 2−ΔΔCt.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE for n = 6–9 independent samples per mice per group. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used when SDs were equal between groups. When the SD between groups was significantly different, a nonparametric t-test was performed (Mann-Whitney test). Statistical significance was accepted when P < 0.05, P < 0.01, or P < 0.001. Statistical analyses were always performed comparing control vs. DSS treatment for each colon section. InStat software (version 3.01; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

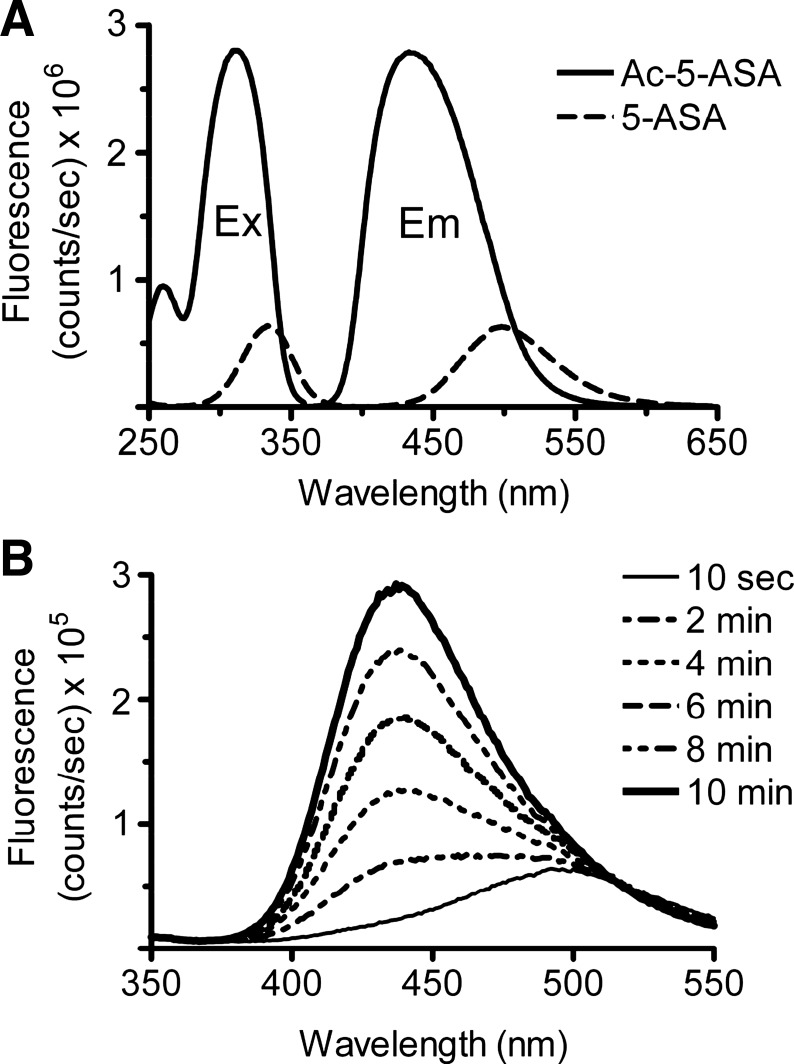

Our initial goal was to establish a simple, sensitive, and specific assay to measure colonic 5-ASA metabolism by NAT enzymes, since existing procedures to measure the Ac-5-ASA metabolite in biological matrixes are time consuming and expensive (16, 34, 48–50). We validated an assay based on the intrinsic fluorescence of Ac-5-ASA. As shown in Fig. 1A, 5-ASA and Ac-5-ASA are fluorescent molecules with distinct excitation and emission wavelengths, and 312 nm excitation with 437 nm emission preferentially detects Ac-5-ASA vs. 5-ASA. In the presence of the NAT cofactor Ac-CoA (420 μM) and the substrate 5-ASA (25 μM), the fluorescence immediately (10 s) after adding colon homogenate had an emission spectrum similar to 5-ASA (500 nm; Fig. 1B). The fluorescence intensity increased over time, with a peak emission wavelength similar to Ac-5-ASA (437 nm). To selectively report production of Ac-5-ASA against the background of 5-ASA fluorescence, linear rate of fluorescence increase at 437 nm emission was quantified for the initial 2 min of reaction.

Fig. 1.

Fluorescence detection of acetyl-5-aminosalicylic acid (Ac-5-ASA). Representative traces of fluorescence intensity vs. wavelength, recorded in a fluorometer cuvette as described in materials and methods. A: fluorescence excitation (Ex) and emission (Em) spectra of 100 μM Ac-5-ASA (solid line, peak excitation 312 nm, peak emission 437 nm) or 100 μM 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA, broken line, peak excitation 335 nm, peak emission 500 nm). Excitation spectra were recorded with 437 nm emission, and emission spectra were recorded with 312 nm excitation. Results show relative efficiency for detecting Ac-5-ASA metabolite vs. 5-ASA substrate. B: fluorescence produced over time by in vitro enzymatic reaction in the presence of 25 μM 5-ASA, 0.4 mM acetyl-coenzyme A (Ac-CoA), and whole colon mucosal homogenate. Ac-CoA was added at time 0, and emission spectra were collected at the indicated time.

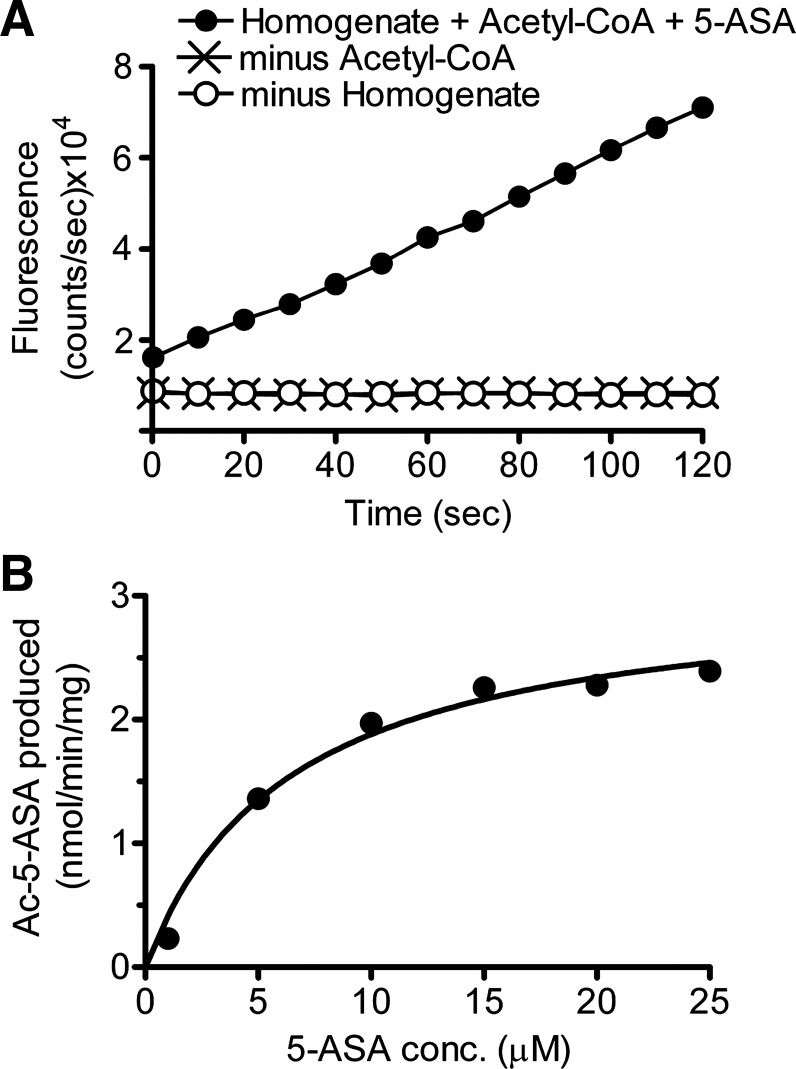

Experiments confirmed that the measured fluorescence increase was dependent on the presence of Ac-CoA, an exogenous source of enzyme (colon homogenate) (Fig. 2A), and was saturable by 5-ASA (Fig. 2B shows a representative experiment). In seven independent experiments using mucosal homogenates from the entire colon, the reaction displayed Michaelis-Menten kinetics with Km (5-ASA) = 5.8 ± 0.3 μM, and Vmax = 2.6 ± 0.2 μM·min−1·mg protein−1. Results confirmed that the assay selectively and quantitatively reported enzymatic acetylation of 5-ASA.

Fig. 2.

In vitro Ac-5-ASA production is via N-acetyltransferase (NAT) enzyme. A: representative time course of fluorigenic reaction when 25 μM 5-ASA is added at time 0 to mixtures that contain whole colon mucosal homogenate plus the NAT cofactor Ac-CoA (0.4 mM) (●), or incomplete mixtures missing either Ac-CoA (x) or colon homogenate (○). B: representative experiment showing calculated Ac-5-ASA production as a function of 5-ASA concentration added to the fluorigenic reaction at time 0 (in the presence of Ac-CoA and whole colon homogenate). Solid line is nonlinear regression fit to Michaelis-Menten kinetics of this individual experiment (Km = 6.4 μM, Vmax = 3.1 nmol·min−1·mg protein−1), with compiled outcomes from multiple experiments presented in results.

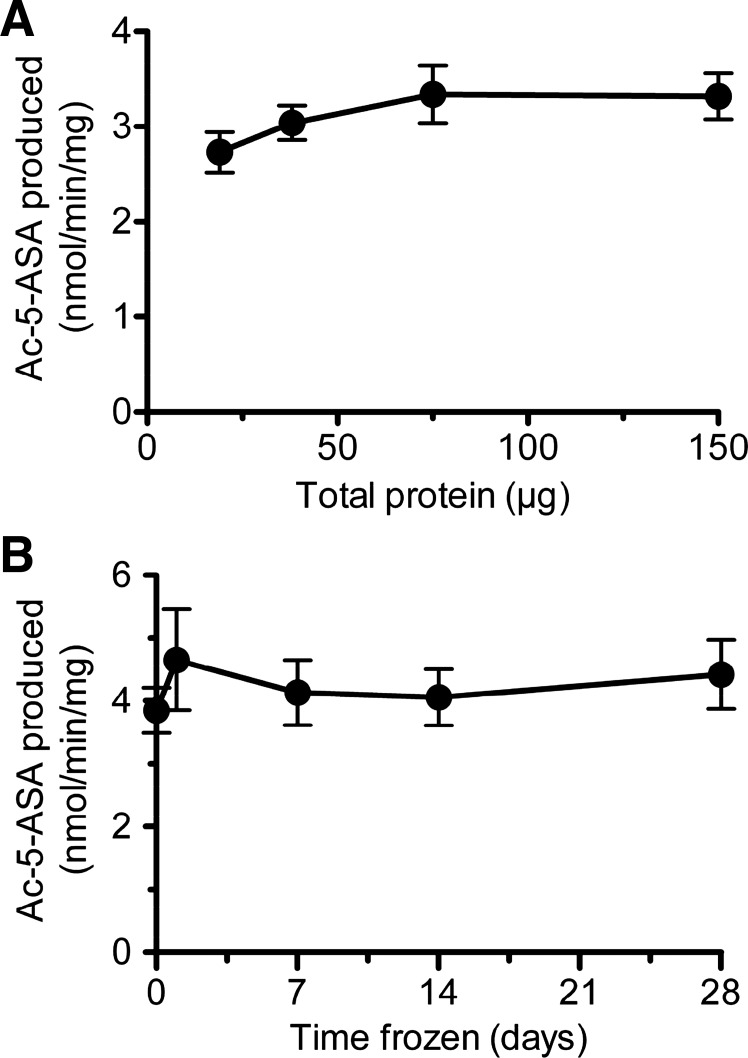

Experiments tested the sensitivity and stability of the measurement. As shown in Fig. 3A, the assay reports comparable NAT activity values with input colonic protein from 20 to 150 μg. Results also showed that 5-ASA acetylation rate was not affected when colonic homogenates were kept frozen at −80°C for up to 4 wk before assay (Fig. 3B). However, enzyme stability was compromised when homogenates were exposed to repeated thaws over the same time interval, with a 14% decrease in activity on the second thaw and a 65% decrease on the fourth thaw (data not shown). All subsequent studies were performed using 75 μg input protein from tissue assayed either fresh or after a single freezing.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity and stability of 5-ASA metabolism measurement. A: metabolic conversion of 5-ASA to Ac-5-ASA is measured in response to varying amounts of whole colon homogenate. Means ± SE, n = 5 mice. B: 5-ASA metabolism measured in fresh homogenates (day 0), or in the same homogenates thawed one time after the indicated time frozen at −80°C. Means ± SE, n = 4 mice.

DSS-induced colitis.

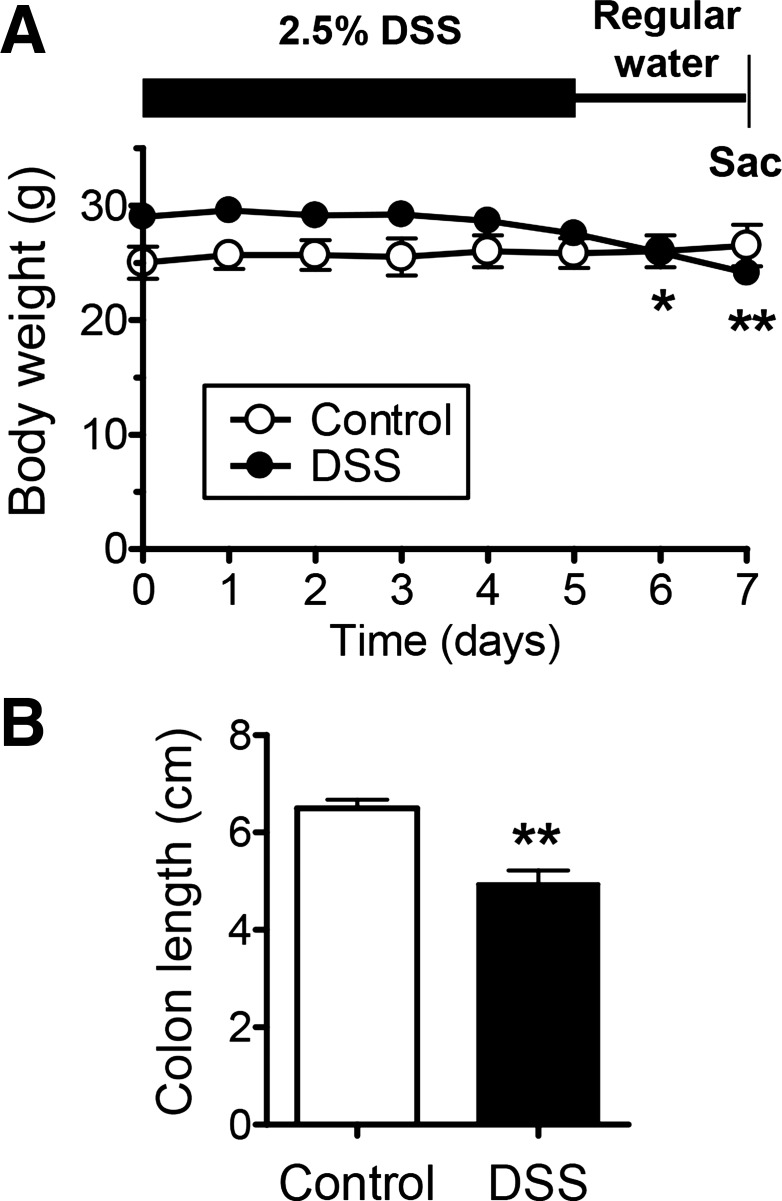

We induced colitis in mice by administration of 2.5% DSS in drinking water for 5 days followed by 2 days of regular drinking water before animal death. A low dose of DSS was used to produce modest damage and hopefully reveal differential sensitivity to injury along the colon length. Treated mice had softened stools and anal bleeding. These changes were accompanied by a modest loss of body weight (Fig. 4A) and colonic shortening compared with controls (Fig. 4B). The small effect on these somewhat nonspecific parameters was likely due to the low concentration of DSS that may have more limited toxic effects.

Fig. 4.

Confirmation and characterization of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. Colitis was induced by replacing regular drinking water with 2.5% DSS for 5 days and then returning to regular drinking water for 2 days before animal death. A: daily weight record of mice getting regular water (control) or 2.5% DSS (DSS) as described above. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. day 0 using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's posttest. B: measured length of excised colon. **P < 0.01 vs. control group. Means ± SE, n = 6 (control) or n = 9 (DSS).

After excision, the colon was divided into three segments (Fig. 5A) so that analyses could be performed in each segment. Figure 5B shows granulocyte infiltration in the mucosa [measured by MPO enzyme activity (40)] increased in each segment after DSS treatment, with the least effect in the proximal colon. MPO activity in the control groups was near the limit of assay detection (2.9 ± 1.4, 3.9 ± 2.7, and 0.1 ± 0.1 mmol H2O2·min−1·mg protein−1 in proximal, central, and distal, respectively, n = 6). Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections (Fig. 5C) confirmed segmental heterogeneity of colitis in four mice. Results demonstrate the most severe colitis in central and distal segments.

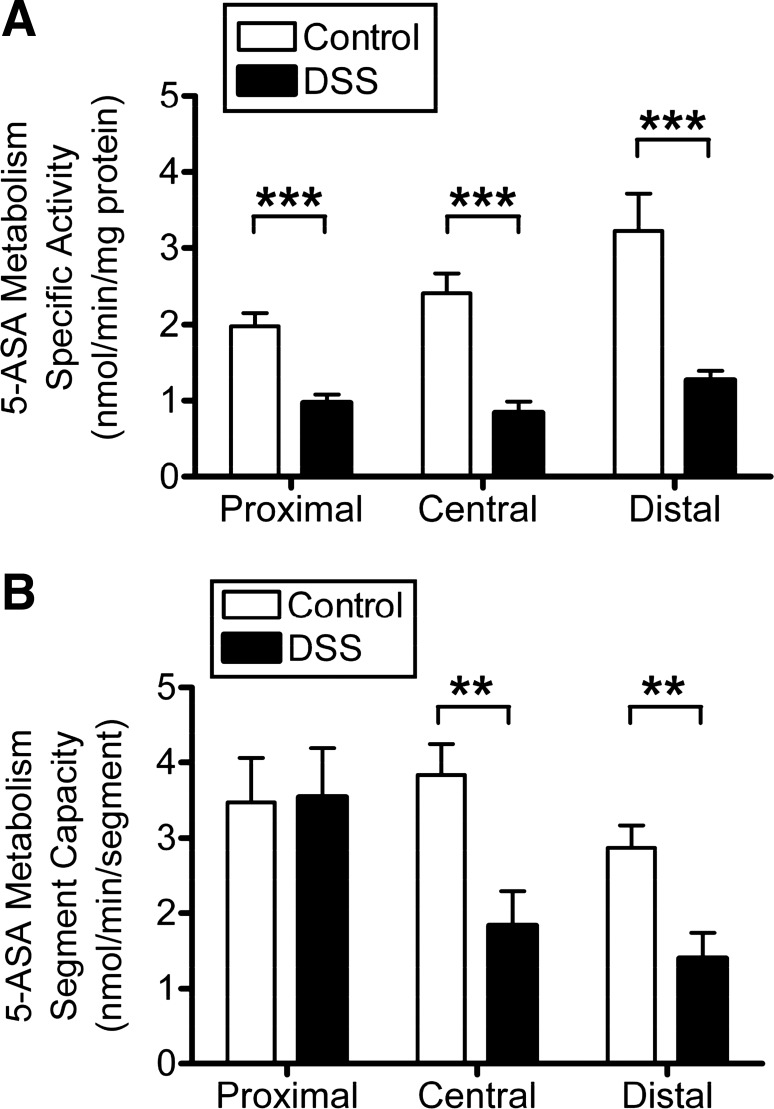

Effect of DSS colitis on mucosal NAT activity.

DSS treatment caused a significant decrease of 5-ASA metabolism (NAT specific activity normalized to protein) in each mucosal segment (48, 62, and 58% decrease in proximal, central, and distal, respectively) compared with the healthy control segment (Fig. 6A). However, we also observed that DSS treatment produced an increase in total mucosal protein content, most prominently in proximal and central segments (data not shown). Therefore, we also quantified total enzyme activity per colon region. This value describes the total capacity for enzymatic conversion encountered by a drug traversing the gut segment. In this alternate analysis (Fig. 6B), no change of enzyme capacity was observed in the proximal colon because of DSS treatment, but central and distal colonic segments had decreased enzyme capacity (52 and 51% decrease in central and distal, respectively). Together, these results demonstrate that DSS colitis can decrease 5-ASA metabolism in more distal gut segments and suggest a segmental heterogeneity in this response that qualitatively correlates with colitis severity.

Fig. 6.

Effect of DSS colitis on 5-ASA metabolism. Fluorimetric NAT activity assay compares mucosal enzyme activity in control mice (white bars) vs. those exposed to DSS (black bars). Excised colon was divided into proximal, central, and distal segments (see Fig. 5A), and their mucosa homogenate was analyzed separately. Means ± SE for n = 6 (control) or n = 9 (DSS). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 comparing DSS treatment vs. corresponding colon segment control. A: NAT metabolism of 5-ASA normalized to the homogenate protein used in the assay. B: NAT metabolism of 5-ASA summed to estimate the total enzyme activity within a given segment, based on the total amount of protein extracted from each colon segment.

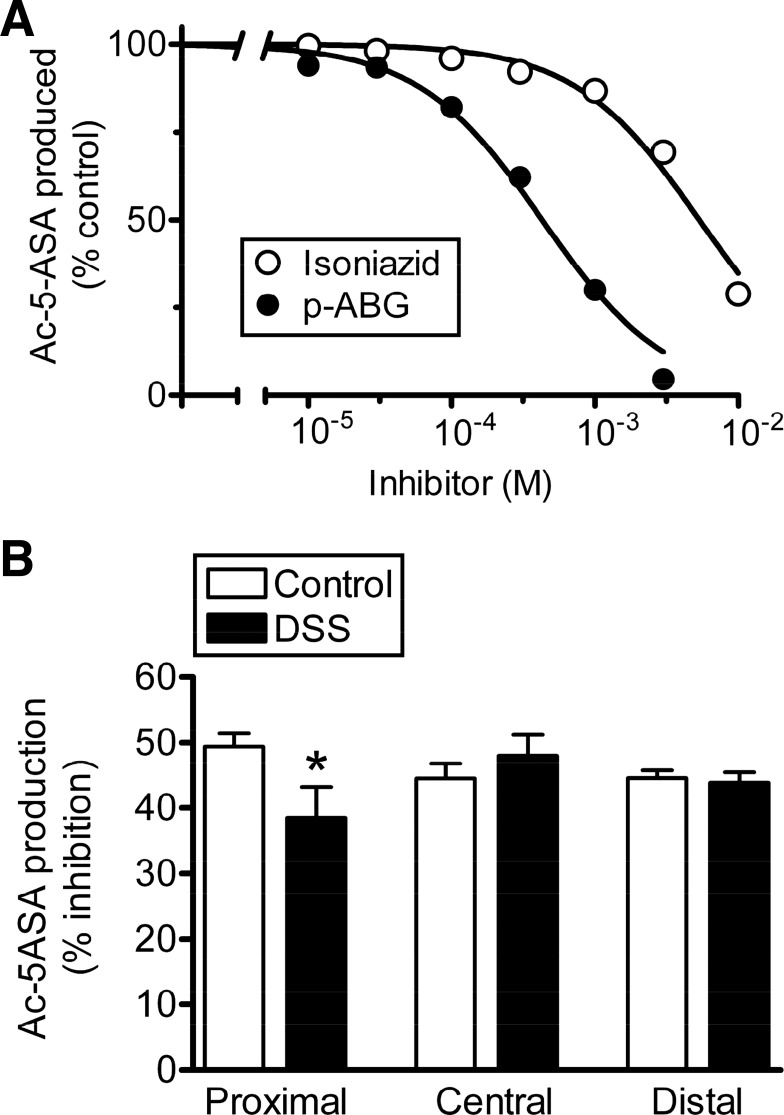

Because 5-ASA is a substrate for all mouse and human NAT isoforms (8, 22, 38) and colonic mucosa expresses at least mNAT1 and mNAT2 (11, 18, 32, 64), we questioned if the basis for altered 5-ASA acetylation during colitis was a change in the contributing mNAT isoform(s). We used substrates shown to be selective for the recombinant mNAT1 (isoniazid) or mNAT2 (p-ABG) (22) and used them as competitive inhibitors of 5-ASA metabolism. In normal colon, both compounds decreased 5-ASA metabolism in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7A), suggesting that at least one of the substrates is not perfectly isoform specific or that 5-ASA metabolism in healthy colon is mediated by both enzymes. As shown in Table 1, the observed IC50 (isoniazid) is a poor match with the predicted IC50 for rat NAT1 (4.5-fold different), but the observed IC50 (p-ABG) is close to the predicted IC50 for the human ortholog of mNAT2 (1.5-fold different). The good curve fits to a single inhibitory site model in Fig. 7A, combined with the analysis of inhibitor potency, suggest that mNAT2 mediates 5-ASA metabolism in the colonic mucosa. Next, we tested if 5-ASA metabolism is more or less sensitive to p-ABG after DSS colitis, as would be predicted if disease shifted the relative contributions of mNAT1 vs. mNAT2 to 5-ASA metabolism. In Fig. 7B, the observed IC50 p-ABG concentration was used (436 μM), and the percent inhibition of Ac-5-ASA production was compared between healthy and colitis tissues. DSS caused the proximal colon to be less sensitive to p-ABG, but no changes were caused by DSS in central or distal colon. In a similar protocol, DSS did not cause any difference in isoniazid sensitivity within any segment (data not shown). Results suggest that, at least in central and distal colon, the acetylation of 5-ASA is mediated by mNAT2 in both healthy and inflamed colon.

Fig. 7.

Potency of isoform-specific NAT substrates to block 5-ASA metabolism in healthy and inflamed colonic mucosa. A: Ac-5-ASA production was measured in the presence of the indicated concentration of a selective substrate for mNAT1 (isoniazid, ○) or mNAT2 [p-aminobenzoylglutamate (p-ABG), ●] as a competitive inhibitor. For each homogenate, results were normalized to the values of Ac-5-ASA production observed in the absence of any inhibitory substance (control). Curves are nonlinear regression fits to a one-site competition binding model, with best-fit values of the inhibitor concentration giving 50% inhibition presented in Table 1. Means ± SE (error bars are smaller than symbols), n = 4 homogenates for each compound. B: Ac-5-ASA production measured in the absence (control) vs. presence of 436 μM p-ABG, and the percent inhibition calculated for homogenates made from healthy colon (white bars) or those exposed to DSS (black bars). Results were measured separately for proximal, central, and distal colon segments as indicated. Means ± SE, n = 6–7 (control) or n = 4–6 (DSS). *P < 0.05 comparing DSS treatment vs. corresponding control.

Table 1.

IC50 values for NAT substrates

| NAT substrate | Observed IC50* | Predicted IC50# |

|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid (mNAT1) | 5,338 ± 411 | 1,182 |

| p-ABG (mNAT2) | 436 ± 22 | 689 |

Units are μM.

Values are mean ± SE; values determined from the experiments compiled in Fig. 7A.

Predicted half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated assuming competition between 25 μM 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and the test compounds. This calculation used the observed IC50, the observed Km (5-ASA) = 5.81 μM, and either the Km (isoniazid) for rat N-acetyltransferase (NAT) 1 [223 μM (56)] or the Km [p-aminobenzoylglutamate (p-ABG)] for human NAT1 that is the mouse NAT2 ortholog [130 μM (43)]. Predicted IC50 = [1 + (25−6/5.8−6)]·Km (competitor).

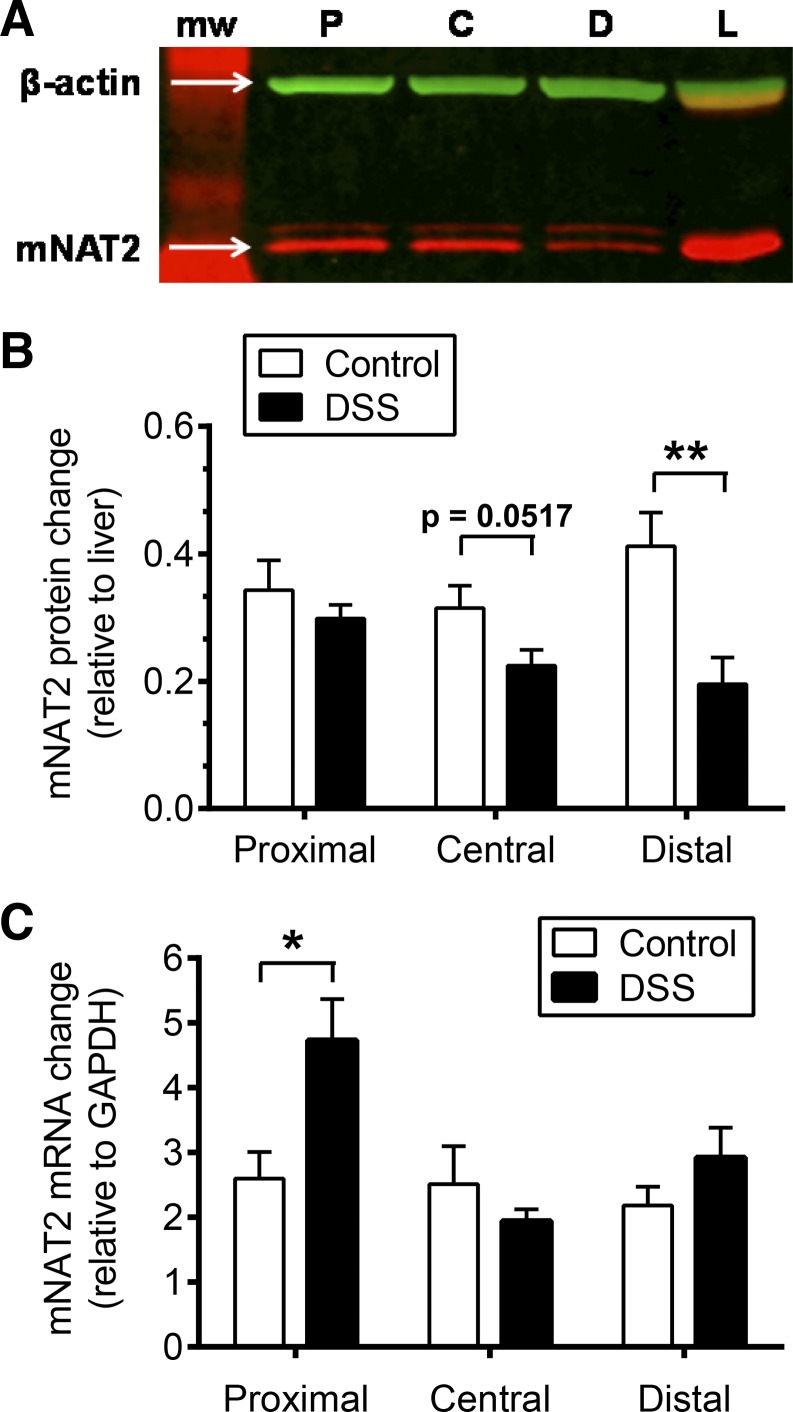

Effect of DSS colitis on mNAT2 protein and mnat2 mRNA.

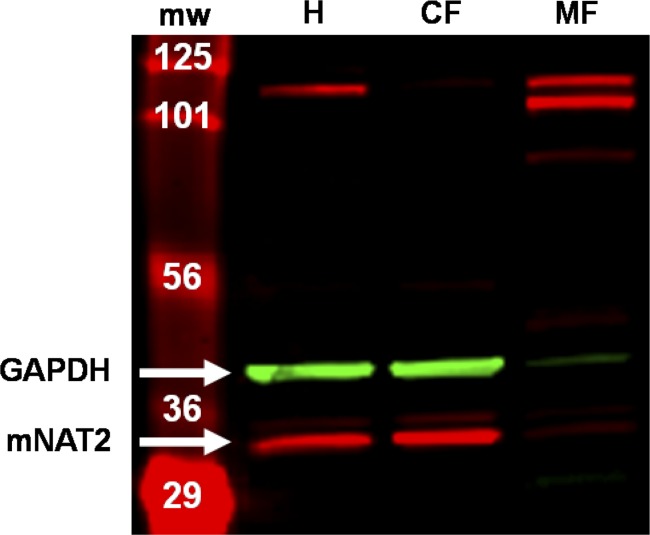

We quantified mNAT2 by Western blot. The mNAT2 antisera identified two bands in total mucosal homogenate from healthy mice (Fig. 8H), with the predicted mNAT2 band at 31 kDa separating into the cytosolic fraction but not membrane fraction. The pattern of mNAT2 protein expression correlated with enzymatic activity where 5-ASA acetylation was 2.14 ± 0.33 and 5.77 ± 0.75 nmol·min−1·mg−1 in total and cytosolic fractions, respectively, whereas activity was deenriched in the membrane fraction (0.13 ± 0.00 nmol·min−1·mg−1). Based on those data, the lower predominant band was measured as representative for mNAT2.

Fig. 8.

Detection of mNAT2 protein in cellular fractions. Representative Western blot membrane visualized on a Li-Cor Odyssey Infrared Imager showing mNAT2 protein (lower predominant red band) and GAPDH (green band) detected on separated proteins of total homogenate (H) and cellular fractions (CF, cytosolic; MF, membrane) from distal colon mucosa of a healthy mouse. NAT2 protein was detected with antisera 195 (kindly provided by Dr. E. Sim, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK). MW, molecular weight marker.

DSS colitis caused a significant reduction in mNAT2 protein in distal colon (54%), a 29% reduction in the central segment that approached significance, and no change in the proximal segment (Fig. 9, A and B).

Fig. 9.

Effect of DSS colitis on mNAT2 protein and mRNA levels. A: representative Western blot showing mNAT2 protein (red band) and β-actin (green band) detected on proximal (P), central (C), and distal (D) colon mucosa homogenates from a mouse with DSS colitis. mNAT2 protein was detected with antisera 195, previously validated in mouse tissues (12). L, liver homogenate. B and C: mucosal colonic tissue from healthy animals (control, white bars) was compared with those with DSS colitis (DSS, black bars) with separate analysis of proximal, central, and distal colon segments as indicated. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 comparing DSS treatment vs. corresponding colon segment control. B: Western blot analyses. β-Actin was used as loading control, and liver homogenate was used as a standard for comparison between blots. Means ± SE, n = 6 (control) or n = 9 (DSS). C: real-time RT-PCR measured mnat2 mRNA of colonic mucosa. For quantification, internal control (GAPDH) and positive control (liver) were used, and data were analyzed by the ΔΔCt method. Means ± SE, n = 4 (control) or n = 7 (DSS).

Real-time RT-PCR analysis measured mnat2 mRNA abundance.

Results showed no significant effect of DSS colitis on mnat2 mRNA abundance in central and distal segments; however, the proximal segment had a significant 1.8-fold increase of mnat2 mRNA level (Fig. 9C). These results suggest that posttranscriptional regulation of mNAT2 protein may explain any reduced NAT activity in central and distal colon and may also explain the reduced ratio of mNAT2 protein/mRNA in the proximal colon segment.

DISCUSSION

IBD disorders expose patients to the consequences of chronic and episodic inflammation of the gut. The drug 5-ASA has been used for decades (in many formulations) as an anti-inflammatory drug to treat mild to moderate UC and Crohn's disease. The pharmacokinetics of the drug include its conversion to N-acetyl 5-ASA as the major metabolite, along with other minor metabolites (2, 19, 60). Whereas inflammation affects therapeutic outcomes by regulating the expression, activity, and functions of many drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters (45, 51, 62, 65), human studies have produced only conflicting reports of whether colonic inflammation affects 5-ASA metabolism (2, 19, 36). We therefore tested in mice if acute inflammation affects N-acetylation of 5-ASA, and the expression and function of the NAT enzymes mediating this metabolic conversion.

We developed, validated, and applied a novel fluorimetric rate assay that directly measured production of Ac-5-ASA by NAT enzymes. A limitation of the rate assay format is that it is not suitable to measure steady-state amounts of Ac-5-ASA in tissue extracts. However, the assay reports enzyme activity, is based on the intrinsic fluorescence of Ac-5-ASA, and does not require any processing or chemical conversion of this NAT enzyme product. This is a divergence from prior work that uses NAT isoform-specific surrogate substrates to measure NAT enzyme activity, and is important because of recent information that both human and mouse orthologs of NAT1 and NAT2 can metabolize 5-ASA (22, 38). Our results with two isoform-selective NAT substrates (22, 38) suggested that mNAT2 mediated the observed 5-ASA metabolism in both healthy and inflamed colon.

We used a mouse model of acute colitis induced by low DSS and documented the presence of a segmentally heterogeneous colitis so that we could evaluate the segmental heterogeneity of 5-ASA acetylation. In future work, it will be important to ask if similar results are observed in chronic colitis models that more closely resemble human IBD, nonmouse models, and in colitides induced by nonchemical means. DSS treatment reduced Ac-5-ASA production, and we observed that DSS caused a decrease in the ratio of mNAT2 protein/mRNA, suggesting posttranscriptional downregulation of mNAT2 during colitis. This posttranscriptional regulation occurs even during a modest inflammation in the proximal colon, where we observed an increase in mnat2 mRNA but no change in mNAT2 protein. More severe inflammation in the central and distal colon correlated with a significant decrease in total 5-ASA metabolism within a gut segment and a reduction in mNAT2 protein, whereas the observation of posttranscriptional regulation was common among all segments. After DSS, epithelial loss was not noted in the proximal colon by pathological assessment (data not shown), and mnat2 mRNA levels were sustained in all colon segments, so results suggest that reduced NAT activity was not due to loss of epithelial cells after DSS exposure.

Our results suggest that DSS reduces colonic 5-ASA metabolism by decreasing mNAT2 protein translation or stability, as well as potentially decreasing enzymatic efficiency (turnover number). This may be due to inflammatory mediators, or a response to the cellular stress from DSS. Butcher et al. also reported evidence for posttranscriptional regulation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which downregulate hNAT1 activity (the mNAT2 ortholog) after exposure to enzyme substrates (10). Other work shows that activity of recombinant hNAT1 protein is directly inhibited by reaction of biological oxidants with a cysteine in the enzyme active site (6, 15). In contrast, when a mixture of proinflammatory cytokines is added to human cholangiocarcinoma cells for 48 h, hNAT1 activity and mRNA are reduced in parallel (8), an outcome that we did not observe in isolated mouse colonic tissue. We speculate that the observed posttranscriptional regulation of colonic mNAT2 activity may be mediated by increased reactive oxygen species in the inflammatory state.

In conclusion, our study validates a reliable method to directly quantify Ac-5-ASA production that is sensitive enough to measure (at least in theory) 5-ASA metabolism in human colonic biopsies. Results show that, in mouse, an acute colonic inflammation impairs the expression and function of mNAT2 enzyme, thereby diminishing the capacity for 5-ASA metabolism. Even a modest inflammation can provoke alterations in the ratio of mNAT2 protein/mRNA. These initial results predict that inflammation will affect the efficacy of 5-ASA therapies against IBD, regardless of whether the effective moiety of therapy is 5-ASA or its metabolite Ac-5ASA. Important areas of future research are to learn whether intracellular drug or metabolite is more active in 5-ASA therapies, and if the same downregulation of 5-ASA metabolism occurs in chronic inflammation. With the use of the new method we introduce, these questions can now be addressed in mice with a confirmed defect in colonic 5-ASA metabolism, or in microscopic samples from human biopsies.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants P30-DK-078392 and UL1-TR-000077. NIH Grant P30-DK-078392 provided support for pathology assessment by Dr. Keith Stringer and statistical direction from Dr. Eileen King.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts (financial, professional or personal) of interest relevant to the conduct of this research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: V.R.-A. and M.H.M. conception and design of research; V.R.-A. performed experiments; V.R.-A. and M.H.M. analyzed data; V.R.-A. and M.H.M. interpreted results of experiments; V.R.-A. prepared figures; V.R.-A. drafted manuscript; V.R.-A. and M.H.M. edited and revised manuscript; V.R.-A. and M.H.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Edith Sim (Oxford, UK) for generously supplying NAT antibodies. We thank Drs. Ted Denson and Tara Wilson for providing protocols related to DSS treatment and supplying an initial aliquot of DSS to start the project. We acknowledge Dr. Andrea Matthis for help with mouse husbandry, Dr. Eitaro Aihara for help with qPCR, Dr. Manuba Matsuda for help with histology, and Chet Closson for technical assistance with the fluorometer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahnfelt-Ronne I, Nielsen OH. The antiinflammatory moiety of sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylic acid, is a radical scavenger. Agents Actions 21: 191–194, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allgayer H, Ahnfelt NO, Kruis W, Klotz U, Frank-Holmberg K, Soderberg HN, Paumgartner G. Colonic N-acetylation of 5-aminosalicylic acid in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 97: 38–41, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allgayer H, Hofer P, Schmidt M, Bohne P, Kruis W, Gugler R. Superoxide, hydroxyl and fatty acid radical scavenging by aminosalicylates. Direct evaluation with electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Biochem Pharmacol 43: 259–262, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allgayer H, Rang S, Klotz U, Bohne P, Retey J, Kruis W, Gugler R. Superoxide inhibition following different stimuli of respiratory burst and metabolism of aminosalicylates in neutrophils. Dig Dis Sci 39: 145–151, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allgayer H, Stenson WF. A comparison of effects of sulfasalazine and its metabolites on the metabolism of endogenous vs. exogenous arachidonic acid. Immunopharmacology 15: 39–46, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atmane N, Dairou J, Paul A, Dupret JM, Rodrigues-Lima F. Redox regulation of the human xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme arylamine N-acetyltransferase 1 (NAT1) Reversible inactivation by hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem 278: 35086–35092, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum M, Grant DM, McBride W, Heim M, Meyer UA. Human arylamine N-acetyltransferase genes: isolation, chromosomal localization, and functional expression. DNA Cell Biol 9: 193–203, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buranrat B, Prawan A, Sripa B, Kukongviriyapan V. Inflammatory cytokines suppress arylamine N-acetyltransferase 1 in cholangiocarcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol 13: 6219–6225, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burress GC, Musch MW, Jurivich DA, Welk J, Chang EB. Effects of mesalamine on the hsp72 stress response in rat IEC-18 intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 113: 1474–1479, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butcher NJ, Ilett KF, Minchin RF. Substrate-dependent regulation of human arylamine N-acetyltransferase-1 in cultured cells. Mol Pharmacol 57: 468–473, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung JG, Levy GN, Weber WW. Distribution of 2-aminofluorene and p-aminobenzoic acid N-acetyltransferase activity in tissues of C57BL/6J rapid and B6. A-NatS slow acetylator congenic mice. Drug Metab Dis 21: 1057–1063, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornish VA, Pinter K, Boukouvala S, Johnson N, Labrousse C, Payton M, Priddle H, Smith AJ, Sim E. Generation and analysis of mice with a targeted disruption of the arylamine N-acetyltransferase type 2 gene. Pharmacogenomics J 3: 169–177, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crotty B, Hoang P, Dalton HR, Jewell DP. Salicylates used in inflammatory bowel disease and colchicine impair interferon-gamma induced HLA-DR expression. Gut 33: 59–64, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crotty B, Rosenberg WM, Aronson JK, Jewell DP. Inhibition of binding of interferon-gamma to its receptor by salicylates used in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 33: 1353–1357, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dairou J, Atmane N, Dupret JM, Rodrigues-Lima F. Reversible inhibition of the human xenobiotic-metabolizing enzyme arylamine N-acetyltransferase 1 by S-nitrosothiols. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 307: 1059–1065, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vos M, Verdievel H, Schoonjans R, Beke R, De Weerdt GA, Barbier F. High-performance liquid chromatographic assay for the determination of 5-aminosalicylic acid and acetyl-5-aminosalicylic acid concentrations in endoscopic intestinal biopsy in humans. J Chromatogr 564: 296–302, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vos M, Verdievel H, Schoonjans R, Praet M, Bogaert M, Barbier F. Concentrations of 5-ASA and Ac-5-ASA in human ileocolonic biopsy homogenates after oral 5-ASA preparations. Gut 33: 1338–1342, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debiec-Rychter M, Land SJ, King CM. Histological localization of acetyltransferases in human tissue. Cancer Lett 143: 99–102, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dilger K, Trenk D, Rossle M, Cap M, Zahringer A, Wacheck V, Remmler C, Cascorbi I, Kreisel W, Novacek G. A clinical trial on absorption and N-acetylation of oral and rectal mesalazine. Eur J Clin Invest 37: 558–565, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egan LJ, Mays DC, Huntoon CJ, et al. , al e. Inhibition of interleukin-1-stimulated NF-kappaB RelA/p65 phosphorylation by mesalamine is accompanied by decreased transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem 274: 26448–26453, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eliakim R, Karmeli F, Chorev M, Okon E, Rachmilewitz D. Effect of drugs on colonic eicosanoid accumulation in active ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 27: 968–972, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Estrada-Rodgers L, Levy GN, Weber WW. Substrate selectivity of mouse N-acetyltransferases 1, 2, and 3 expressed in COS-1 cells. Drug Metab Dis 26: 502–505, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Everhart J. Inflammatory bowel diseases. In: The Burden of Digestive Diseases in the United States, edited by Everhart J. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford AC, Kane SV, Khan KJ, Achkar JP, Talley NJ, Marshall JK, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in Crohn's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 106: 617–629, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galvez J, Garrido M, Rodriguez-Cabezas ME. The intestinal anti-inflammatory activity of UR-12746S on reactivated experimental colitis is mediated through downregulation of cytokine production. Inflammatory Bowel Dis 9: 363–371, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grisham MB, Miles AM. Effects of aminosalicylates and immunosuppressive agents on nitric oxide-dependent N-nitrosation reactions. Biochem Pharmacol 47: 1897–1902, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hausmann M, Paul G, Menzel K, Brunner-Ploss R, Falk W, Scholmerich J, Herfarth H, Rogler G. NAT1 genotypes do not predict response to mesalamine in patients with ulcerative colitis. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie 46: 259–265, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkey CJ, Boughton-Smith NK, Whittle BJ. Modulation of human colonic arachidonic acid metabolism by sulfasalazine. Dig Dis Sci 30: 1161–1165, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hearse DJ, Weber WW. Multiple N-acetyltransferases and drug metabolism. Tissue distribution, characterization and significance of mammalian N-acetyltransferase. Biochem J 132: 519–526, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hein DW. Acetylator genotype and arylamine-induced carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 948: 37–66, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hein DW, Doll MA, Fretland AJ, Leff MA, Webb SJ, Xiao GH, Devanaboyina US, Nangju NA, Feng Y. Molecular genetics and epidemiology of the NAT1 and NAT2 acetylation polymorphisms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevention 9: 29–42, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hickman D, Pope J, Patil SD, Fakis G, Smelt V, Stanley LA, Payton M, Unadkat JD, Sim E. Expression of arylamine N-acetyltransferase in human intestine. Gut 42: 402–409, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horvath K, Varga C, Berko A, Posa A, Laszlo F, Whittle BJ. The involvement of heme oxygenase-1 activity in the therapeutic actions of 5-aminosalicylic acid in rat colitis. Eur J Pharmacol 581: 315–323, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hussain FN, Ajjan RA, Kapur K, Moustafa M, Riley SA. Once versus divided daily dosing with delayed-release mesalazine: a study of tissue drug concentrations and standard pharmacokinetic parameters. Alimen Pharmacol Ther 15: 53–62, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ilett KF, Ingram DM, Carpenter DS, Teitel CH, Lang NP, Kadlubar FF, Minchin RF. Expression of monomorphic and polymorphic N-acetyltransferases in human colon. Biochem Pharmacol 47: 914–917, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ireland A, Priddle JD, Jewell DP. Acetylation of 5-aminosalicylic acid by isolated human colonic epithelial cells. Clin Sci 78: 105–111, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ireland A, Priddle JD, Jewell DP. Comparison of 5-aminosalicylic acid and N-acetylaminosalicylic acid uptake by the isolated human colonic epithelial cell. Gut 33: 1343–1347, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawamura A, Graham J, Mushtaq A, Tsiftsoglou SA, Vath GM, Hanna PE, Wagner CR, Sim E. Eukaryotic arylamine N-acetyltransferase. Investigation of substrate specificity by high-throughput screening. Biochem Pharmacol 69: 347–359, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly SL, Sim E. Arylamine N-acetyltransferase in Balb/c mice: identification of a novel mouse isoenzyme by cloning and expression in vitro. Biochem J 302: 347–353, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krawisz JE, Sharon P, Stenson WF. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Assessment of inflammation in rat and hamster models. Gastroenterology 87: 1344–1350, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loehle JA, Cornish V, Wakefield L, Doll MA, Neale JR, Zang Y, Sim E, Hein DW. N-acetyltransferase (Nat) 1 and 2 expression in Nat2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319: 724–728, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loftus EV., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology 126: 1504–1517, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minchin RF. Acetylation of p-aminobenzoylglutamate, a folic acid catabolite, by recombinant human arylamine N-acetyltransferase and U937 cells. Biochem J 307: 1–3, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moolenbeek C, Ruitenberg EJ. The “Swiss roll”: a simple technique for histological studies of the rodent intestine. Lab Animals 15: 57–59, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan ET, Goralski KB, Piquette-Miller M, Renton KW, Robertson GR, Chaluvadi MR, Charles KA, Clarke SJ, Kacevska M, Liddle C, Richardson TA, Sharma R, Sinal CJ. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in infection, inflammation, and cancer. Drug Metab Disposition 36: 205–216, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy SJ, Wang L, Anderson LA, Steinlauf A, Present DH, Mechanick JI. Withdrawal of corticosteroids in inflammatory bowel disease patients after dependency periods ranging from 2 to 45 years: a proposed method. Alimen Pharmacol Ther 30: 1078–1086, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nielsen OH, Verspaget HW, Elmgreen J. Inhibition of intestinal macrophage chemotaxis to leukotriene B4 by sulphasalazine, olsalazine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. Alimen Pharmacol Ther 2: 203–211, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nobilis M, Vybiralova Z, Sladkova K, Lisa M, Holcapek M, Kvetina J. High-performance liquid-chromatographic determination of 5-aminosalicylic acid and its metabolites in blood plasma. J Chromatogr A 1119: 299–308, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palumbo G, Bacchi S, Primavera L, Palumbo P, Carlucci G. A validated HPLC method with electrochemical detection for simultaneous assay of 5-aminosalicylic acid and its metabolite in human plasma. Biomed Chromatogr 19: 350–354, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pastorini E, Locatelli M, Simoni P, Roda G, Roda E, Roda A. Development and validation of a HPLC-ESI-MS/MS method for the determination of 5-aminosalicylic acid and its major metabolite N-acetyl-5-aminosalicylic acid in human plasma. J Chromatogr B 872: 99–106, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petrovic V, Teng S, Piquette-Miller M. Regulation of drug transporters during infection and inflammation. Mol Interventions 7: 99–111, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pompeo F, Brooke E, Kawamura A, Mushtaq A, Sim E. The pharmacogenetics of NAT: structural aspects. Pharmacogenomics 3: 19–30, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reifen R, Nissenkorn A, Matas Z, Bujanover Y. 5-ASA and lycopene decrease the oxidative stress and inflammation induced by iron in rats with colitis. J Gastroenterol 39: 514–519, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ricart E, Taylor WR, Loftus EV, O'Kane D, Weinshilboum RM, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. N-acetyltransferase 1 and 2 genotypes do not predict response or toxicity to treatment with mesalamine and sulfasalazine in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 97: 1763–1768, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rousseaux C, Lefebvre B, Dubuquoy L, Lefebvre P, Romano O, Auwerx J, Metzger D, Wahli W, Desvergne B, Naccari GC, Chavatte P, Farce A, Bulois P, Cortot A, Colombel JF, Desreumaux P. Intestinal antiinflammatory effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid is dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Exp Med 201: 1205–1215, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schneck DW, Sprouse JS, Hayes AH, Jr, Shiroff RA. The effect of hydralazine and other drugs on the kinetics of procainamide acetylation by rat liver and kidney N-acetyltransferase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 204: 212–218, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sim E, Walters K, Boukouvala S. Arylamine N-acetyltransferases: from structure to function. Drug Metab Rev 40: 479–510, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simmonds NJ, Millar AD, Blake DR, Rampton DS. Antioxidant effects of aminosalicylates and potential new drugs for inflammatory bowel disease: assessment in cell-free systems and inflamed human colorectal biopsies. Alimen Pharmacol Ther 13: 363–372, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stanley LA, Mills IG, Sim E. Localization of polymorphic N-acetyltransferase (NAT2) in tissues of inbred mice. Pharmacogenetics 7: 121–130, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tjornelund J, Hansen SH, Cornett C. New metabolites of the drug 5-aminosalicylic acid. II. N-formyl-5-aminosalicylic acid. Xenobiotica 21: 605–612, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Hogezand RA, van Hees PA, van Gorp JP, van Lier HJ, Bakker JH, Wesseling P, van Haelst UJ, van Tongeren JH. Double-blind comparison of 5-aminosalicylic acid and acetyl-5-aminosalicylic acid suppositories in patients with idiopathic proctitis. Alimen Pharmacol Ther 2: 33–40, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vet NJ, de Hoog M, Tibboel D, de Wildt SN. The effect of inflammation on drug metabolism: a focus on pediatrics. Drug Discovery Today 16: 435–442, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.von Ritter C, Grisham MB, Granger DN. Sulfasalazine metabolites and dapsone attenuate formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine-induced mucosal injury in rat ileum. Gastroenterology 96: 811–816, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ware JA, Svensson CK. Longitudinal distribution of arylamine N-acetyltransferases in the intestine of the hamster, mouse, and rat. Evidence for multiplicity of N-acetyltransferases in the intestine. Biochem Pharmacol 52: 1613–1620, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitehouse MW. Abnormal drug metabolism in rats after an inflammatory insult. Agents Actions 3: 312–316, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Willoughby CP, Piris J, Truelove SC. The effect of topical N-acetyl-5-aminosalicylic acid in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 15: 715–719, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamada T, Volkmer C, Grisham MB. The effects of sulfasalazine metabolites on hemoglobin-catalyzed lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med 10: 41–49, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]