Abstract

The earliest archaeological remains of dwelling huts built by Homo sapiens were found in various European Upper Paleolithic open-air camps. Although floors of huts were found in a small number of cases, modern organization of the home space that includes defined resting areas and bedding remains was not discovered. We report here the earliest in situ bedding exposed on a brush hut floor. It has recently been found at the previously submerged, excellently preserved 23,000-year-old fisher-hunter-gatherers' camp of Ohalo II, situated in Israel on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. The grass bedding consists of bunches of partially charred Puccinellia confer convoluta stems and leaves, covered by a thin compact layer of clay. It is arranged in a repeated pattern, on the floor, around a central hearth. This study describes the bedding in its original context on a well preserved intentionally constructed floor. It also reconstructs on the basis of direct evidence (combined with ethnographic analogies) the Upper Paleolithic hut as a house with three major components: a hearth, specific working locales, and a comfortable sleeping area near the walls.

The houses of many contemporary hunter-gatherers have a hearth, as well as a clean and debris-free resting and sleeping area, covered for comfort by grasses, mats, carpets, etc. Within the house or immediately annexed to it, as part of the living area, are various task areas devoted to specific activities, especially those related to the preparation, consumption, or storage of food and those concerned with activities such as tool production or use (1, 2). This kind of divided living space represents a use of space that reflects attention to safety and health, as well as comfort, and may be what we think of as sophisticated living space standards similar to our own in certain respects but rarely visible in the prehistoric archaeological record.

Several components of human domestic behavior are well documented even in Middle Paleolithic cave sites (ca. 150,000-45,000 years ago), where simple hearths are preserved. Around the hearths, food remains such as bones and very rarely even seeds and fruits, as well as flint tools and their production waste, are sometimes concentrated in nonrandom patterns, reflecting activities carried out near the fire (3-5). However, the locations of areas devoted to resting and sleeping are not known, because bedding was not preserved. If there had been any floor coverings or bedding, they would have been made of perishables, and these substances do not readily lend themselves to preservation. Thus, a major component of the house, the sleeping/resting area, has never been clearly identified in a Middle Paleolithic site.

This paper presents the earliest archeological indication of a home space that includes bedding remains. Interestingly, it does not come from a cave site but rather from an open-air camp, Ohalo II (23,000-year-old site, Sea of Galilee, Israel). The in situ bedding remains were exposed on a brush hut floor, around a hearth, and with other facilities and residues. We begin by briefly addressing the issue of perishable materials in Paleolithic sites; we then present the Ohalo II Paleolithic camp and focus on the bedding and variety of finds from the brush hut intentionally constructed floors. Finally, a short comparison to European contemporaneous dwellings, Neolithic structures, and ethnographic examples shows that the Ohalo II remains provide the earliest Paleolithic case of a brush hut with evidence of domestic behavior including a central hearth and defined locations for eating, working, and sleeping.

Paleolithic Perishables

The Ohalo II perishables are unique and are a major focus of this paper, given the large quantity and wide variety of relevant materials that were preserved in their original context. However, the use of plant materials by humans during the Upper Paleolithic was undoubtedly common and had begun long before. Thus, wood was preserved in rare cases as early as the Lower Paleolithic period, as evidenced by various wooden objects that include polished items from Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, a 780,000-year-old site in the Jordan Valley (6, 7), and the long carefully sharpened wooden spears from Shoningen, a 400,000-year-old site in Germany (8). It is probable that during these early times, most manufactured wooden items were used for hunting, digging up roots, and other practical purposes (9). Evidence of earlier woodworking and possibly even the preparation of wooden implements by bifacial stone tools was recently provided with the presentation of 1.7- to 1.5-million-year-old artifacts from Peninj, Tanzania (10). Even in much later Upper Paleolithic sites, well preserved wooden objects are still extremely rare, although several have been found at Ohalo II.

Soft plant fibers associated with human use have a lower survival and preservation rate and an even lower chance than wood of surviving the vagaries of time. Indeed, direct indications for the use of fibers begin to appear in the archaeological record, in extremely small numbers and usually in a very fragmentary state, only at ≈26,000 years B.P. in Moravia (11). Inferences to clothing made of perishables that could have included plant fibers followed the study of European Upper Paleolithic female figurines, some of which appear to be clothed (12). Other remains have also been found, such as the charred fragments of a thick rope from Lascaux Cave, dated to ca. 17,000 B.P. (13). Larger quantities and a wider variety of remains of basketry, netting, and textiles are more commonly encountered only much later, in the early Holocene, as documented for sites in the Mediterranean Levant (14, 15) and in South and North America (16, 17).

The Ohalo II Site

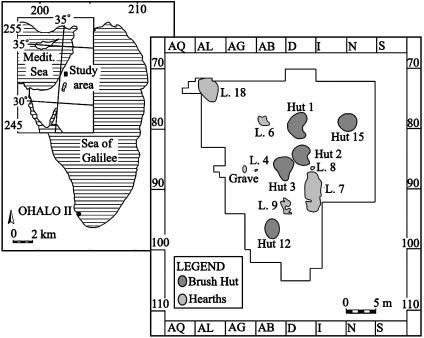

The Ohalo II site is located on the southwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel, at 212-213 m below mean sea level (Fig. 1). It was submerged during most of its history and even most of the 20th century. Since 1989, during 7 nonsuccessive years of severe drought and heavy pumping from the lake, the water level dropped far enough to expose the site and permit excavation.

Fig. 1.

Location map of Ohalo II on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel (Left), and a plan of the central area of excavation showing the location of brush huts, hearth concentrations, and a grave (Right).

The visible in situ remains of the prehistoric camp covered >2,000 m2, of which ≈500 were excavated. During excavation, we found the remains of six brush huts that had apparently burned down in antiquity (18, 19). The floors of four brush huts were fully excavated, whereas two others were largely sampled. All were rich with food remains, bones, seeds, fruits, and flint-knapping debris and were clearly distinct from the surrounding fine-grained lacustrine stone-free deposits (see below). All huts were generally oval in shape, with a north-south long axis.

Near the huts, six concentrations of open-air hearths were exposed. Each concentration included the remains of several hearths, sometimes partially overlapping. This phenomenon indicates that in each of these locations, fires were used at different times. Therefore, we can assume that camp life included cooking and other fire-related activities in specific open-air locations. Typical debris of food preparation and flint working was common near most hearths.

A grave of an adult male was discovered near the huts. The skeleton was buried in a flexed position, on the back, with hands folded on the chest (20). The man was 1.73 m tall and almost 40 years old at the time of death. Shoulder, elbow, forearm, and hand development indicate he was a right-handed thrower and thruster (possibly of spears directed at game or fish) (21). Anatomically, he shows affinities to the later Natufian (ca. 12,500-10,300 years B.P.) population.

There are 45 radiocarbon dates from the archaeological layer as well as from earlier and later sedimentological strata. The average age of 25 relevant 14C dates (all obtained from charcoal samples) is 19,470 years B.P., which is ≈23,000 years after calibrations (22, 23). No material remains belonging to other archaeological cultures were found.

Charred seeds and fruit were common in all parts of the camp. A sample of 90,000 specimens was studied, mostly from huts 1 and 3 (24, 25). It includes the remains of >100 species, of which wild cereals (such as wild barley, Hordeum spontaneum) are very common. The wide range of species, gathered and used during all seasons, reflects the presence of three distinct habitats: a local saline habitat, a nearby lakeshore habitat, and a Mediterranean open park-like forest, probably on the slopes surrounding the Sea of Galilee basin. The species diversity is very similar to plant communities growing in the Jordan Valley and surrounding hills today.

More than 8,000 mammal bones were studied, of which those of gazelles (Gazella gazella) were the most abundant. There are also bones of fallow deer, fox, and hare, among others (26). Bird bones of >80 species were identified, with waterfowl being the most common (27). The range of bird species represents at least three seasons of occupation. The bones found in greatest abundance at the site belong to small fish of the Cyprinidae and Cichlidae families (28). Thus, subsistence appeared to be based on a combination of fishing, hunting, and gathering of a wide range of species on a year-round basis. This conclusion is reasonable, given that water, a variety of terrestrial and aquatic food sources, and raw materials were permanently within reach of the lakeshore camp.

The lakeshore setting provided all subsistence requirements, and during periods of occupation, there was no apparent need to move the residential camp to other locations. However, our geological observations indicate intermittent episodes of occupation and inundation. The latter probably forced the inhabitants to abandon the camp during spells of high water levels. The entire sequence of occupations and inundations represents a relatively short period, most probably not more than several generations altogether. The last inundation was of a greater magnitude. Calm relatively deep water covered the site, and the immediate deposition of fine clay and silt layers began (29, 30). Together, the water and sediments sealed the site and protected the remains in situ for millennia. Since then, the rate of decomposition has been extremely low in the submerged anaerobic conditions and the preservation of the organic material has been excellent.

Brush Hut Floors

The floors of dwellings in Paleolithic camps are rarely preserved, and their identification by archaeologists is somewhat controversial. However, the identification of Paleolithic floors is a major research goal, because the remains on these floors attest to the variety of domestic activities carried out in the house. In many societies, such activities include food preparation, consumption, or storage, as well as tool production and use in a variety of subsistence-, social- and spiritual-related activities (1, 2). Less obvious archaeologically, but no less important, the remains on the floors can also be informative in terms of the arrangement and maintenance of resting and sleeping areas.

At Ohalo II, good preservation rendered possible field definition of floors, supported by geological studies and later analyses of artifact distributions. Here, floors were classified as dark anthropogenic layers that were oval-shaped and measured several centimeters thick, could be distinguished macroscopically and microscopically from surrounding layers and deposits by color and matrix and were rich in charcoal, bones, flints, and other everyday debris (30, 31). The floors of six oval brush huts were identified. Their lengths were 2-5 m, and they ranged between 5-13 m2 in area. In section, each was like a shallow bowl, slightly sunken below ground level (19, 32). Neither the floors nor the foundations of the walls were constructed with stones.

Hut 1

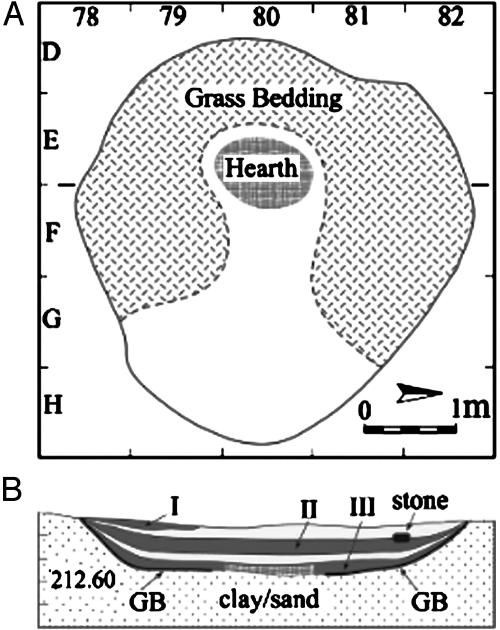

In hut 1, we found charred remains that formed a continuous oval line delimiting the floor (19). These remains included thick fragments (up to 5 cm in diameter) of tamarisk (Tamarix), willow (Salix), and oak (Quercus ithaburensis) branches, as well as smaller elements of a variety of species. The anthropogenic sediment in most of the huts was 10-20 cm thick. In hut 1, however, it was even thicker in the center, permitting us to distinguish three successive floors (Fig. 2). Between them were irregular layers of bright clay and silt, usually 3-5 cm thick, with few anthropogenic remains. The three floors were black (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and rich with remains of food processing and flint knapping, although the top floor was preserved on only one side of the hut.

Fig. 2.

Brush hut 1 at the Ohalo II camp. (A) Plan showing the floor III area and the distribution of the grass bedding (GB) around the ashes near the wall. In many ethnographic cases, it is common to find bedding around the walls and not in the center. (B) Section showing the position of floor III within the sequence of three floors (shaded, marked I-III) and the in-between layers (bright), and the location of the grass bedding at the bottom. Numbers on the left represent the height (in meters) below sea level.

The fully exposed second floor yielded, among other finds, a large flat in situ basalt stone positioned horizontally on a patch of yellow sand and carefully supported by several small pebbles. No such arrangement was documented elsewhere at the site. The large quantities of finds from this floor were meticulously studied and mapped. Discrete concentrations of identified seeds of several species lay around the stone. Products of flint knapping were also very common on the floor but showed no association with the flat stone. Rather, the highest concentration was found near the entrance and was composed of cores, and thousands of knapping products (especially bladelets), tools as well as an overwhelming quantity of minute debris and fragments (<1 cm). The overlapping distributions of large and tiny flints indicate no cleaning or sweeping of the floor. Around the concentration was an arch-shaped area with very few flints. This pattern resembles that created by two or three knappers sitting in a semicircle and manufacturing flint tools (31). Relatively large numbers of tools were found near the walls, and it is likely that the tools were either leaning against or hanging on the walls. Distinct concentrations of small fish vertebrae (mostly 2-5 mm in diameter) and other skeletal elements were found on the floor, possibly representing stored fish in hanging baskets that fell to the floor while the hut was burning (18).

We suggest that the distribution patterns of seeds, bones, and flints are not random. An accumulation of such a variety of remains by a natural postoccupation process would have created a different picture. First, most, if not all, light delicate materials (e.g., seeds, fish vertebrae, and tiny pieces of flint) would have been carried away by wave action or even strong winds and not preserved in large quantities on the floor. Second, the concentrations of seeds, flints, and fish bones do not overlap, indicating that the accumulation was not confined to depressions in the floor, into which all remains would have been carried by water. Because all remains were found on the same thin dark anthropogenic layer, which included the set of an in situ flat stone and its foundation, a nonanthropogenic agent responsible for the distinct distribution patterns should be ruled out.

A refitting endeavor of the hut 1 flints is now under way. As yet, >100 pieces have been refitted, showing that knapping (as well as breakage) took place in the hut, and that flints were not washed into the floor depression after the hut was abandoned. Refitting of flints from hut 2 presents similar results, with >50 refitted pieces. Refitting of fire-shattered flint cores from hut 13 was also successful. There are several refits of basalt implements found on the hut floors. In addition, articulated animal bones were observed on some of the floors. Furthermore, large erect stones were found in one hut and near two other huts, and small erect stones were found under the floors of two huts (23, 32). The latter were set erect, as some kind of foundation or symbolic elements, before the time when the floors were used for accommodation purposes. Altogether, each of the field observations and research results (e.g., distribution patterns and flint refitting) provides independent support for our claim of in situ preservation on the Ohalo II hut floors (30-32).

Furthermore, thin sections of the hut 1 floors and the in-between layers, which were analyzed under an optical polarized light microscope, verify the presence of in situ floors (30, 33). The bottom floor, on which the bedding remains were preserved, is a complex depositional unit composed of pedogenetically reworked, bioturbated calcareous clay containing 10% silt, occasional rounded basaltic clasts, and abundant charcoal fragments. Charcoal occurred alongside weathered or heated bone chips, all juxtaposed with calcareous nodules and lacustrine foraminifera. The microscopic remains reveal an episode of hut occupation, during which small fragments of plant material and bones were trampled into the matrix and thereby underwent distinct depositional processes.

To conclude, the hut 1 floors attest to indoor knapping and use of flint and basalt, as well as to plant and animal food preparation/storage/consumption. On the same floors were several polished points made of gazelle bones, probably used for piercing soft materials, weaving, or as needles/pins. Furthermore, at least 40 Dentalium and 10 Columbella beads made of shell were preserved in hut 1. Both species are found in the Mediterranean Sea, attesting to long-range connections between the Ohalo II people and the coastal plain.

The Bedding Remains

Most of the bottom floor of hut 1 (≈7 m2) seems to have been covered with grasses, with only the central area of the hut devoid of such remains (Fig. 2). About1min diameter, this central area contained white ash mixed with charcoal fragments. No stones were found around or in the ashes. This is probably where a central hearth was occasionally burning. Hearths were not visible in other fully excavated huts.

The grass remains were laid in a planned arrangement (Fig. 3) near the walls and around the central hearth. Only the hearth and the entrance were devoid of the charred grasses. It is most probable that this arrangement reflects the original distribution pattern and is not the product of biased preservation. Importantly, flint and basalt implements, animal bones, and charred seeds were found in the layer on top of the grass covering, but almost none underneath it.

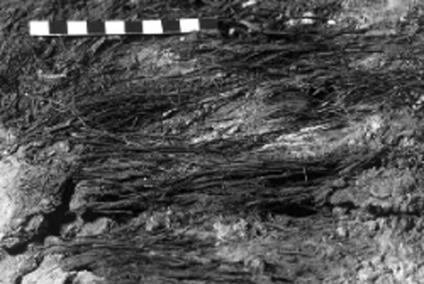

Fig. 3.

Grass bedding, in situ, on the bottom floor of brush hut 1 during excavation (scale in cm).

The preserved remains of the grass bedding consisted of a horizontal layer, up to 1 cm thick, of bunches of shoots (leaf-carrying stems), the longest of which measured ≈30 cm (Fig. 3). Generally found side by side, the shoots in the best-preserved location formed a shingle-like arrangement, in which the bases of one row overlapped the top of the leaves of the previous row. Some bunches lay at a 90° angle to others. In one location, several delicate stems were found in a probable loose warp and weft pattern, although the fragmentary nature does not permit a conclusive statement.

Because no roots were found on any of the grasses, which exhibit the full aboveground length typical of the species, we may speculate that the inhabitants used sharp flint tools to cut the grasses just above root level. Although the grasses appeared to have been spread flat on the floor without being tied, tiny charred remains of cords discovered elsewhere in the hut (18) suggest that the grasses might have been tied in large bundles for transport.

The floor covering was made up of several thousand shoots. When excavated, the shoots were extremely fragile and tended to crumble on handling. After examining the morphology and anatomy of all of the plant components, we identified one species as the grass used almost exclusively for the covering: Puccinellia, probably Puccinellia convoluta (Hornem.) P. Fourr., belonging to a group of closely related tufted perennials named Puccinellia gigantea (Grossh.) Grossh. s.l. (34, 35) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Micrograph of a Puccinellia confer convoluta shoot with the basal part of the flowering stem crowded by open leaf sheaths. Visible on both sides are the short narrow outer leaf sheaths. The uppermost sheaths firmly clasp the peduncle with their overlapping margins, and some leaf sheaths still retain their scabridulous margins. The fibrous roots are missing.

Most of the shoots are somewhat bent at the base, with a slender erect stem measuring 1.0-1.5 mm in diameter (Fig. 4). The leaf blades are linear, with numerous minute teeth along their margins. The glumes are lanceolate, acute, and shorter than the lemmas. Anatomical studies reveal that the shoots are somewhat oval in cross section, with a cavity at the center. The epidermis is subtended by a continuous zone of fibers, and numerous columns of assimilatory tissue are embedded in the sclerenchyma. A cross section of the leaf blade shows that most of the vascular bundles are small and not conspicuously angular in outline. Bulliform cells are clearly present (36). The ensemble of features is characteristic of Puccinellia.

Adhering to the top and bottom of the grass layer, a compacted crust-like material was noted. In thin sections, the grass tissues are closely associated with this material, which consists of a mixture of charred remains and calcareous clay that varies in thickness from 1 to 7 mm (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Charred grass fragments are packed in the clay matrix with a density that suggests intentional compaction. When handled, the compacted crust-like layer peels off in a continuous strip. No such material was found adhering to any other of the abundant plant specimens at the site.

Two tentative explanations for the origin of the substance are offered at present. It is possible that hides or furs were placed on top of the grass cover, and while the hut was burning, fats or other organic compounds were melted and then embedded with clay in-between and especially over the grasses, creating the observed crust. Alternatively, the inhabitants used an unknown material that included a sticky, compact, clayey substance to protect and keep together the tightly arranged grasses, thereby creating a simple, thin, two-layer “mat.” We believe that only a protective layer would explain why the delicate grass material is preserved almost in its entirety in an undisturbed arrangement, despite trampling during constant use of the floor, destruction of the hut by fire, and the same area's reoccupation, with a second floor constructed only months or so later. Such preservation would have been almost impossible without a protective layer.

Both field and microscope studies strongly suggest that the grasses, along with the adhering compacted layer, did not constitute a collapsed roof. This is supported by the lack of grass remains above the central hearth. Had the grasses been a part of the roof, they should have covered the ashes of the hearth, too. Moreover, material remains of mundane activities are rare under the grass layer and abundant above it in all parts of the floor. Thus, the grass layer formed an in situ floor covering (as suggested by petrographic thin sections) placed at an early phase of hut use. It was probably used for sleeping, but also for comfort during daily activities carried out in the hut.

The season in which the grasses were gathered is difficult to determine. Because the species is perennial, plants gathered during any season would include dry stems from previous seasons, green parts, and some ears. However, botanical (24, 25) and faunal (27) remains from hut 1 and other huts represent all four seasons and thus suggest that the camp was occupied year-round.

The best-preserved bedding in the site was found on the bottom floor of hut 1. However, in the same hut, a distinct microscopic layer of horizontal grass fragments was also found on the second floor (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Furthermore, the floor in each of two other huts (huts 3 and 12; see Fig. 1) exhibited a continuous millimeter-thick black layer at the bottom. In both of these huts, the layer was situated above the bedrock clay, under the typical debris of everyday activities and always within the boundary of the hut. Also in both, it was preserved near the walls and not in the center. Thus, the inhabitants appear to have covered the floor with plant material in at least three huts. In hut 1, the bottom bedding was well preserved, whereas the grass cover on a later floor in the same hut was visible only in microscopic thin sections. In all three huts, the grass layers were preserved in situ but only as a compact black layer (except for the bottom floor of hut 1), with no identifiable details regarding the species or arrangement of the grasses. It is possible that in these cases, the grass layer was not protected in the same manner as the bedding from the bottom floor of hut 1, and therefore preservation is not as good.

Bedding and Perishables

To create their bedding, the Ohalo II people chose a grass species characterized by dense bunches of soft delicate stems, which was growing in nearby saline soil. At the same time in Upper Paleolithic European sites, plant fibers were being used for manufacturing various products, as evidenced by the small clay fragments with impressions of cordage, textile, and basketry found at Moravian sites (11) and the female figurines wearing clothing and headgear found at other European sites (12). The suggestion that some of the clay fragments with fiber impressions could represent “floor coverings or sitting/sleeping platform coverings” (37) is possible, although it is based on very small fragments, none of which were found in situ as part of a floor.

At Ohalo II, several cord fragments were discovered on the second floor of hut 1 (18). These attest to the presence of local fiber technology, possibly representing rope use, basketry, and netting. Tens of double-notched pebbles and the plethora of fish remains probably indicate the presence of fishing technology that included simple fishing nets composed of plant fibers and stone weights (38). However, although the preservation of delicate plant tissues is excellent at the site, no remains of woven mats were identified. It is therefore possible that the Ohalo II grass floor coverings represent the first stage of bedding, whereas fully woven mats evolved only millennia later.

Upper Paleolithic Dwellings

The Upper Paleolithic material remains demonstrate what could be termed a “revolution” in many aspects of technology, economy, social organization, and spiritual life (39). Within this sphere of innovations, the archaeological evidence includes open-air camps with dwelling remains. In the better-preserved sites, several dwellings are found together, similar to each other in dimensions and shape. The structures are commonly round or oval, built of local materials such as stones (for wall foundations), large bones, or wood and thatch. Hides were probably used as well, although no remains have been preserved.

In Eastern Europe, especially in the Russian Plain, round dwellings constructed of heavy mammoth bones were common in many sites (40). These had an inner diameter of 2-5 m, with storage pits placed outside. The Ohalo II huts are similar in size and shape to many of these northern huts. Small shallow hearths were found outside and even inside some of the European dwellings. Food preparation and flint knapping took place inside, too, at least in some cases. In a minority of sites, excavations exposed very large shallow pits with an inner line of small hearths, and an area exceeding 100 m2 (41). If these were indeed dwellings, they were probably occupied by much larger-sized groups than that of a nuclear family.

In Western Europe (France, for example), paved and stone-lined rectangular or subrectangular areas were interpreted as floors or hut foundations (42). The floor areas were usually 6-15 m2. Of particular interest is the site of Pincevent, where the location and size of small round dwellings were reconstructed according to the distribution patterns of flints and bones and not by the remains of defined walls or floors (43). In sum, dwellings with an indoor or annexed hearth, and sometimes with identifiable indoor working areas, have been preserved in several European sites. However, a dwelling with all three components, a hearth, a defined working area, and a preserved sleeping area with bedding, was found only at Ohalo II.

In the Mediterranean Levant, dwelling remains that are contemporaneous with or even thousands of years later than the Ohalo II finds are very rare and ambiguous in nature, because no full contours of walls or floors are clearly preserved. Indeed, the earliest stone foundations of walls appear in several Natufian open-air camps and cave sites (44, 45). The remains of Natufian structures are typically oval or circular and contain debris of domestic activities; built indoor hearths have also been found in many cases. Although tens of Natufian structures have been excavated, no grass floor coverings or mats have been found.

Discussion

Evidence of floor covering in the house is extremely scarce in sites of the Upper Paleolithic period. In the Mediterranean Levant, the remains of matting, weaving, and textile production have been discovered at several Neolithic sites, with the earliest specimens dating almost 10,000 years later than the remains at Ohalo II. For example, impressions of large round mats were preserved on floors and courtyards in Pre-Pottery Neolithic Jericho (14), where the long stems and wide leaves of reeds were commonly used. The fabrics, baskets, and mats from the somewhat later Nahal Hemar desert cave (ca. 9,000 years B.P.) constitute by far the largest, best-preserved, and most varied assemblage of any Levantine Neolithic site (15).

In the Americas, the oldest remains of fiber-based technology include cordage, basketry, textile, and netting; they are found across the continents, from Monte Verde in Chile (dated to the 11-10th millennia B.C., ref. 16) to many sites in North America. The oldest remains of mats from North America were recently reported from Nevada, dated to 10,500 calendar years B.P. (17).

The practice of covering floors with mats, rugs, and carpets has parallels in many recent and contemporary hunter-gatherer and non-Western societies throughout the world. Also common is the choice of fresh local grasses, whose proximity demands a minimum of effort, for producing floor coverings and bedding that provide comfort and insulation from harsh temperatures, as well as a pleasant fragrance (46, 47). In fact, grass floor coverings even appear in cases where mats, carpets, or blankets are used (48). The 19th and 20th centuries still witnessed the practice of placing a simple bedding material, such as a grass floor covering, all along the walls of a room (48-50) and arranging bunches of stems with leaves in straight parallel sets (51).

The discovery at Ohalo II of a complex bedding, composed of thick grass bunches arranged in a tile-like manner and attached to each other by a compact layer of clay substance, is the earliest in situ example of the common modern practice of making the sleeping area comfortable. This was achieved by creating a soft layer on the floor, but only near the walls and not in the center. The Ohalo II remains reveal new aspects of life during the Upper Paleolithic period, indicating that technologies and routine activities did not focus exclusively on activities directly related to survival. The new finds are not surprising, because several aspects of the Ohalo II camp are similar to those recorded in ethnography (1, 2). They do confirm that by that time, comfort in the home was also an important consideration, as it is for us today. People invested in their sleeping area by bringing bundles of one chosen grass species and constructing sophisticated bedding with the use of an adhesive substance. Other parts of the covered floor were used for tool preparation and food processing around the hearth, near the hut entrance, or next to a large flat stone. This conception and organization of the domestic space are similar to the modern home.

No grass bedding remains were found in contemporaneous European sites, probably due to poor preservation conditions, lack of suitable species, or a preference for skins and furs in the colder zones. True woven mats, which can be viewed as a further development of the first bedding reported here, are not found before the Middle Eastern Neolithic period. The mats were made in a tight warp and woof pattern and were much stronger than the Ohalo II grass bedding. The Neolithic mats were portable, thus facilitating transportation from the place of manufacture to the house and increasing cleanliness by allowing the dirt to be shaken off outside. The Ohalo II bedding and associated finds, preserved in situ on the same floor, add to our understanding of the organization of the indoor house space and the origin of a variety of modern domestic behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ofer Bar-Yosef, Anna Belfer-Cohen, and Paul Goldberg for improving an early version of the manuscript, and Yossi Zaidner for contribution during field and laboratory work. The drawings in Figs. 1 and 2 were made by Sapir Ad (Zinman Institute of Archaeology) and Bella Burdman (Zinman Institute of Archaeology), and Fig. 4 represents a photograph by Yaaqov Langzam (Bar Ilan University). E.W. is the MacCurdy Postdoctoral Fellow of the Department of Anthropology, Harvard University. The Ohalo II project was generously supported by the Irene Levi Sala Care Archaeological Foundation, the Israel Academy of Science (Grant 831/0), the Jerusalem Center for Anthropological Studies, the L. S. B. Leakey Foundation, the M. Stekelis Museum of Prehistory in Haifa, the MAFCAF Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and the Israel Antiquities Authority.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.O'Connell, J. F. (1987) Am. Antiq. 52, 74-108. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, R. B. & DeVore, I. (1976). Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers. Studies of the !Kung San and Their Neighbours (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 3.Bar-Yosef, O., Vandermeersch, B., Arensburg, B., Belfer-Cohen, A., Goldberg, P., Laville, H., Meignen, L., Rak, Y., Speth, J. D., Tchernov, E., Tillier, A.-M. & Weiner, S. (1992) Curr. Anthropol. 33, 497-550. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaquero, M. & Pasto, I. (2001) J. Arch. Sci. 28, 1209-1220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rigaud, J.-P., Simek, J. F. & Ge, T. (1995) Antiquity 69, 902-912. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goren-Inbar, N., Belitzki, S., Verosub, K., Werker, E. Kislev, M. E., Heimann, A., Carmi, I. & Rosenfeld, A. (1992) Q. Res. 38, 117-128. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goren-Inbar, N., Werker, E. & Feibel, C. S. (2002) The Acheulian Site of Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel: The Wood Assemblage (Oxbow, Oxford).

- 8.Thieme, H. (1997) Nature 385, 807-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bamford, M. K. & Henderson, Z. L. (2003) J. Arch. Sci. 30, 637-651. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominguez-Rodrigo, M., Serrallonga, J., Juan-Tresserras J., Alcala L. & Luque, L. (2001) J. Hum. Evol. 40, 289-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soffer, O., Adovasio, J. M., Illingworth, J. S., Amirkhanov, H. A., Praslov, N. D. & Street, M. (2000) Antiquity 74, 812-821. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adovasio, J. M., Soffer, O., Hyland, D. C., Illingworth, J. S., Klima, B. & Svoboda, J. (2001) Archa. Ethno. Anthropol. 2, 48-65. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leroi-Gourhan, A. (1982) Sci. Am. 246, 80-88.6281879 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenyon, K. M. (ed.). (1981) Excavations at Jericho (British School of Archeology, Jerusalem), Vol. III.

- 15.Bar-Yosef, O. & Alon, D. (1988) 'Atiqot 15, 31-43. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adovasio, J. M. (1997) in Monte Verde: A Late Pleistocene Settlement in Chile, ed. Dillehay, T. D. (Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC), pp. 221-228.

- 17.Fowler, C. S., Hattori, E. M. & Dansie, A. J. (2000) in Beyond Cloth and Cordage: Archaeological Textile Research in the Americas, eds. Drooker, P. B. & Webster, L. D. (Univ. of Utah Press, Salt Lake City), pp. 119-139.

- 18.Nadel, D., Danin, A., Werker, E., Schick, T., Kislev, M. E. & Stewart, K. (1994) Curr. Anthropol. 35, 451-458. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadel, D. & Werker, E. (1999) Antiquity 73, 755-764. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadel, D. & Hershkovitz, I. (1991) Curr. Anthropol. 32, 631-635. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershkovitz, I., Spiers, M. S., Frayer, D., Nadel, D., Wish-Baratz, S. & Arensburg, B. (1995) Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 96, 215-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadel, D., Carmi, I. & Segal, D. (1995) J. Arch. Sci. 22, 811-822. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadel, D., ed.. (2002) Ohalo II—A 23,000 Year-Old Fisher-Hunter-Gatherers' Camp on the Shore of the Sea of Galilee (Hecht Museum, Haifa, Israel).

- 24.Kislev, M. E., Nadel, D. & Carmi, I. (1992) Rev. Palaeobot. Palyn. 73, 161-166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kislev, M. E., Simchoni, O. & Weiss, E. (2002) in Ohalo II: A 23,000 Year-Old Fisher-Hunter-Gatherers' Camp on the Shore of the Sea of Galilee, ed. Nadel, D. (Hecht Museum, Haifa, Israel), pp. 21-23.

- 26.Rabinovich, R. (2002) in Ohalo II—A 23,000 Year-Old Fisher-Hunter-Gatherers' Camp on the Shore of the Sea of Galilee, ed. Nadel, D. (Hecht Museum, Haifa, Israel), pp. 24-27.

- 27.Simmons, T. & Nadel, D. (1998) Int. J. Osteoarch. 8, 79-96. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zohar, I. (2002) in Ohalo II—A 23,000 Year-Old Fisher-Hunter-Gatherers' Camp on the Shore of the Sea of Galilee, ed. Nadel, D. (Hecht Museum, Haifa, Israel), pp. 28-31.

- 29.Belitzky, S. & Nadel, D. (2002) Geoarcheology 17, 453-464. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsatskin, A. & Nadel, D. (2003) Geoarcheology 18, 409-432. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadel, D. (2001) Lithic. Technol. 26, 118-137. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nadel, D. (2003) Archa. Ethnol. Anthropol. Euroasia 13, 34-48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courty, M.-A., Goldberg, P. & Macphail, R. (1989) Soils and Micromorphology in Archaeology (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K.).

- 34.Davis, P. H. (1985) Flora of Turkey (University Press, Edinburgh), Vol. 9, p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsvelev, N. N. (1983) Grasses of the Soviet Union (Amerind, New Delhi), pp. 760-761.

- 36.Metcalfe, C. R. (1960) in Anatomy of the Monocotyledons, 1. Gramineae (Clarendon Press, Oxford), pp. 415-418.

- 37.Soffer, O., Adovasio, J. M. & Hyland, D. C. (2000) Archa. Ethnol. Anthropol. Euroasia 1, 37-47. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadel, D. & Zaidner, Y. (2002) J. Israel Prehist. Soc. 32, 49-72. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bar-Yosef, O. (2002) Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 31, 363-393. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soffer, O. & Praslov, N. D. (1993) From Kostenki to Clovis. Upper Palaeolithic-Palaeo-Indian Adapatations (Plenum, New York).

- 41.Grigor'ev, G. P. (1967) Curr. Anthropol. 8, 344-349. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaussen, J. (1980) Le Paléolithique Supérieur de Plein Air en Périgord (Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris).

- 43.Leroi-Gourhan, A. & Brezillon, M. (1972) Feuilles de Pincevent: Essai d'Analyse Ethnographique d'un Habitat Magdalenien (Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris), Section 36.

- 44.Bar-Yosef, O. (1998) Evol. Anthropol. 6, 159-177. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belfer-Cohen, A. (1991) Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 20, 167-186. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levine, D. N. (1965) in Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopian Culture (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago), pp. 62, 246.

- 47.Mair, L. P. (1934) in An African People in the Twentieth Century (Russell, New York), pp. 84, 108.

- 48.Barrett, S. A. (1916) in Pomo Buildings (Bryan, Washington, DC), p. 10.

- 49.Stern, T. (1965) The Klamath Tribe: A People and their Reservation, (Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle).

- 50.Chapman, A. (1982) in Drama and Power in a Hunting Society: The Selk'nam of Tierra del Fuego (Cambridge Univ. Press, New York), pp. 27-28.

- 51.Roscoe, J. (1966) in The Baganda: An Account of Their Native Customs and Beliefs (Macmillan, London), pp. 89, 376.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.