Abstract

Background

Changes in adverse-event rates among Medicare patients with common medical conditions and conditions requiring surgery remain largely unknown.

Methods

We used Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System data abstracted from medical records on 21 adverse events in patients hospitalized in the United States between 2005 and 2011 for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, or conditions requiring surgery. We estimated trends in the rate of occurrence of adverse events for which patients were at risk, the proportion of patients with one or more adverse events, and the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations.

Results

The study included 61,523 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (19%), congestive heart failure (25%), pneumonia (30%), and conditions requiring surgery (27%). From 2005 through 2011, among patients with acute myocardial infarction, the rate of occurrence of adverse events declined from 5.0% to 3.7% (difference, 1.3 percentage points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7 to 1.9), the proportion of patients with one or more adverse events declined from 26.0% to 19.4% (difference, 6.6 percentage points; 95% CI, 3.3 to 10.2), and the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations declined from 401.9 to 262.2 (difference, 139.7; 95% CI, 90.6 to 189.0). Among patients with congestive heart failure, the rate of occurrence of adverse events declined from 3.7% to 2.7% (difference, 1.0 percentage points; 95% CI, 0.5 to 1.4), the proportion of patients with one or more adverse events declined from 17.5% to 14.2% (difference, 3.3 percentage points; 95% CI, 1.0 to 5.5), and the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations declined from 235.2 to 166.9 (difference, 68.3; 95% CI, 39.9 to 96.7). Patients with pneumonia and those with conditions requiring surgery had no significant declines in adverse-event rates.

Conclusions

From 2005 through 2011, adverse-event rates declined substantially among patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure but not among those hospitalized for pneumonia or conditions requiring surgery. (Funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and others.)

Patient safety poses serious challenges to the health care system in the United States.1-5 Since 2001, nationwide efforts have focused on reducing in-hospital adverse events over the past decade. From 2001 through 2011, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) awarded approximately $532 million for research on patient safety.6 In July 2002, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (later renamed the Joint Commission) initiated National Patient Safety Goals and requirements for its accredited organizations. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement introduced the 100,000 Lives Campaign in 2004 and the 5 Million Lives Campaign in 2006.7,8 During the same time frame, important legislation regarding patient safety was signed into law,9-12 guidelines were changed to improve patient safety,13-15 and specific measurements of adverse events were developed.16,17

Extensive nationwide efforts have focused on improving care processes and outcomes, starting with Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction, in 1992,18,19 and those with congestive heart failure or pneumonia, in 1998.20 For patients undergoing surgery, the American College of Surgeons launched its National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in 1994 at veterans' hospitals and extended it to private-sector hospitals in 2001. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, initiated the Surgical Infection Prevention Project in 2002, and a consortium of government agencies and nongovernmental organizations established the Surgical Care Improvement Project in 2005, with the aim of reducing surgical complications.21 The cardiovascular care community, in particular, has embraced quality improvements for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure by launching national registries, developing performance measures and appropriate-use criteria, and initiating national quality-improvement campaigns.22,23

The effects of these efforts are not clear. Previous examinations of trends in patient safety were limited with respect to regions, measures, sample sizes, and data sources.24-28 Temporal changes in adverse-event rates on a national scale remain unknown. Meanwhile, hospitalization rates, 30-day mortality rates, care patterns, condition-specific procedure rates, and lengths of stay for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and conditions requiring surgery have changed over the past decades.29-33 Little is known about whether these changes and national quality-improvement efforts have affected the safety of patients hospitalized with these conditions. We used the Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System (MPSMS),34 a large database of information abstracted from medical records of a random sample of hospitalized patients, to assess trends in adverse-event rates among those hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, or conditions requiring surgery during the period from 2005 through 2011 across all states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico.

Methods

Study Sample

The MPSMS was initiated by the CMS in 2001 to monitor and track in-hospital adverse events among Medicare patients. MPSMS data are available for in-hospital adverse events from 2002 through 2011, with the exception of 2008, when no data were abstracted. The current 21 measures, jointly developed by federal agencies and private health care organizations, are considered to be indicators of safety and can be reliably abstracted from medical records (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org).34 From 2002 through 2007, the MPSMS randomly selected a sample from the CMS Hospital Payment Monitoring Program. The annual sample included approximately 26,000 Medicare medical records from more than 4000 hospitals for all medical conditions. In 2009, the AHRQ assumed leadership and funding of the MPSMS project. From 2009 through 2011, the MPSMS obtained all payer data from the CMS Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting program, including data for patients with acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, or conditions requiring surgery. During this transition, a new variable was added to the MPSMS data to determine whether Medicare was the primary payer.

Approximately 17,500 records were acquired from 4000 hospitals for 2009, and 34,000 were acquired from approximately 1400 randomly selected hospitals for 2010 and 2011. Of the 1400 hospitals, each contributed an approximately equal number of records to the MPSMS (Appendix A in the Supplementary Appendix). The CMS Clinical Data Abstraction Center abstracted all medical records. The agreement rates between abstraction and re-abstraction ranged from 94% to 99% for data elements used to identify adverse events.34-37 Because data on all 21 measures were available beginning in 2005, we restricted our sample to all Medicare patients 65 years of age or older who had acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, or conditions requiring surgery and who were discharged between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2011. This approach excluded 77.6% of the records from 2005 through 2007 and 48.4% of the records from 2009 through 2011 but facilitated the comparison of data across all years.

In-Hospital Adverse Events

We divided the 21 events for which patients were at risk during hospitalization into four clinical categories: adverse drug events, general events, hospital-acquired infections, and postprocedural events (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Appendix B in the Supplementary Appendix provides algorithms for the measures.

There were three composite outcomes for the 21 measures: the rate of occurrence of adverse events for which patients were at risk (e.g., although all patients were at risk for falls, only patients who received warfarin were at risk for a warfarin-associated adverse event), the proportion of patients with one or more adverse events, and the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations. The unit of analysis was at the individual adverse-event level for the first outcome and at the patient level for the other two outcomes (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). If an adverse event could be counted more than once (e.g., some cases of postoperative pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia), only one was included in the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations. Using the 2010–2011 data, we assessed the association of adverse events with in-hospital mortality and length of stay.

Statistical Analysis

We fitted a linear mixed-effects model with a Poisson link function to evaluate the trend in the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations. We fitted the mixed model with a logit link function to evaluate trends in the rate of occurrence of adverse events and the proportion of patients with one or more adverse events. All models were fitted with state-specific random intercepts to account for within-state and between-state variations and were adjusted for patient characteristics (age, sex, race, and coexisting conditions). All models included an ordinal time variable that ranged from 0 to 5, corresponding to years 2005 (time = 0) through 2011 (time = 5), with 2008 excluded, to represent the annual change in adverse-event rates. The odds ratios for the time variable were converted to relative risk ratios with the use of the method of Zhang and Yu38 to report the relative risk reduction in adverse-event rates. Models were fitted for each condition separately. Analyses were conducted with the use of SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute). To facilitate data presentation and increase the sample in the baseline period, patient characteristics and adverse-event rates were reported in 2-year intervals: 2005–2006, 2007–2009 (excluding 2008), and 2010–2011; these represent the baseline, midpoint, and end-of-study periods.

Results

Study Sample

The final study sample included 61,523 patients — 11,399 with acute myocardial infarction, 15,374 with congestive heart failure, 18,269 with pneumonia, and 16,481 with conditions requiring surgery — from 2005 through 2011 and across a total of 4372 hospitals. No hospital was included in every year — that is, none of the hospitals had one or more cases for all four conditions in all 6 years (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). For all years combined, there were 612 patients with acute myocardial infarction (5.4%), 70 with congestive heart failure (0.5%), and 100 with pneumonia (0.5%) who underwent at least one surgical procedure and were therefore also included in the subsample of patients with conditions requiring surgery. Coexisting conditions increased over time across the four conditions (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). In 2010–2011, the top five principal discharge diagnoses in surgical patients were osteoarthritis and allied disorders (39%), fracture of the neck of the femur (10%), malignant neoplasm of the colon (5%), acute myocardial infarction (5%), and other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease (4%). This pattern did not change substantially over the study period.

All hospitalized patients were at risk for at least 2 adverse events: falls and pressure ulcers acquired during hospitalization. The number of events per hospitalization for which patients were at risk varied according to the condition and patient attributes, ranging from 2 to 18, but remained similar over the study period (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The percentage of patients at risk varied over the study period according to the adverse event (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). In 2010–2011, approximately 52% of patients with acute myocardial infarction, 37% with congestive heart failure, 41% with pneumonia, and 100% with conditions requiring surgery were at risk for 7 or more adverse events during hospitalization (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Trends in Adverse-Event Rates

Between 2005 and 2011, observed adverse-event rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction and those with congestive heart failure declined significantly for all three outcomes: the rate of occurrence of adverse events for which patients were at risk declined by 1.3 percentage points (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7 to 1.9), from 5.0% to 3.7% (acute myocardial infarction), and by 1.0 percentage points (95% CI, 0.5 to 1.4), from 3.7% to 2.7% (congestive heart failure); the proportion of patients with one or more adverse events declined by 6.6 percentage points (95% CI, 3.3 to 10.2), from 26.0% to 19.4% (acute myocardial infarction), and by 3.3 percentage points (95% CI, 1.0 to 5.5), from 17.5% to 14.2% (congestive heart failure); and the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations declined by 139.7 (95% CI, 90.6 to 189.0), from 401.9 to 262.2 (acute myocardial infarction), and by 68.3 (95% CI, 39.9 to 96.7), from 235.2 to 166.9 (congestive heart failure) (P<0.01 for trend for all comparisons). The rates of occurrence of adverse events among patients with pneumonia and those with conditions requiring surgery did not change. Patients with conditions requiring surgery had slight decreases and patients with pneumonia had slight increases in the other two outcomes. Figure S2 in the Supplementary Appendix shows the relative changes in adverse-event rates between 2005 and 2011 for the three outcomes. Table 1 shows the observed 2-year combined adverse-event rates.

Table 1.

Adverse Events from 2005–2006 to 2010–2011.*

| Event | Acute Myocardial Infarction | Congestive Heart Failure |

Pneumonia | Conditions Requiring Surgery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2006 | 2007 and 2009† | 2010–2011 | 2005–2006 | 2007 and 2009† | 2010–2011 | 2005–2006 | 2007 and 2009† | 2010–2011 | 2005–2006 | 2007 and 2009† | 2010–2011 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| number of events/total number (percent) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Adverse drug events | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with digoxin | 0/85 | 2/124 (1.6) | 7/398 (1.8) | 1/514 (0.2) | 1/393 (0.3) | 5/963 (0.5) | 0/310 | 3/370 (0.8) | 5/628 (0.8) | 1/187 (0.5) | 3/126 (2.4) | 1/215 (0.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with hypoglycemic agents | 72/550 (13.1) | 100/866 (11.5) | 325/3033 (10.7) | 162/1062 (15.3) | 152/1288 (11.8) | 497/3946 (12.6) | 121/1012 (12.0) | 224/1685 (13.3) | 460/3921 (11.7) | 181/1613 (11.2) | 152/1650 (9.2) | 270/2710 (10.0) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with IV heparin | 96/540 (17.8) | 78/625 (12.5) | 216/2123 (10.2)‡ | 24/189 (12.7) | 15/132 (11.4) | 40/301 (13.3) | 17/99 (17.2) | 10/95 (10.5) | 63/284 (22.2) | 146/567 (25.7) | 66/258 (25.6) | 140/437 (32.0)§ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with LMW heparin and factor Xa inhibitor | 47/566 (8.3) | 54/962 (5.6) | 158/3658 (4.3)‡ | 32/731 (4.4) | 27/973 (2.8) | 95/3317 (2.9) | 40/750 (5.3) | 50/1571 (3.2) | 192/4081 (4.7) | 195/1605 (12.1) | 181/2055 (8.8) | 414/3748 (11.0) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with warfarin | 12/150 (8.0) | 16/231 (6.9) | 40/693 (5.8) | 29/727 (4.0) | 24/798 (3.0) | 85/2335 (3.6) | 38/426 (8.9) | 35/683 (5.1) | 130/1441 (9.0) | 130/1555 (8.4) | 72/1420 (5.1) | 154/2056 (7.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| General events | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers | 69/1360 (5.1) | 114/2223 (5.1) | 409/7816 (5.2) | 154/2689 (5.7) | 162/3268 (5.0) | 511/9417 (5.4) | 262/2889 (9.1) | 404/4900 (8.2) | 987/10,480 (9.4) | 256/4814 (5.3) | 243/4855 (5.0) | 485/7594 (6.4)¶ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Inpatient falls | 17/1360 (1.3) | 34/2223 (1.5) | 62/7816 (0.8)¶ | 36/2689 (1.3) | 46/3268 (1.4) | 111/9417 (1.2) | 40/2889 (1.4) | 81/4900 (1.7) | 134/10,480 (1.3) | 79/4814 (1.6) | 75/4855 (1.5) | 90/7594 (1.2)§ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hospital-acquired infections | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile infection | 4/587 (0.7) | 5/955 (0.5) | 15/3484 (0.4) | 8/1283 (0.6) | 4/1642 (0.2) | 21/4878 (0.4) | 28/2850 (1.0) | 33/4841 (0.7) | 83/10,361 (0.8) | 22/4703 (0.5) | 17/4781 (0.4) | 33/7558 (0.4) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Central catheter–associated bloodstream infections | 4/205 (2.0) | 3/273 (1.1) | 8/743 (1.1) | 3/124 (2.4) | 0/101 | 2/338 (0.6) | 0/40 | 1/38 (2.6) | 2/109 (1.8) | 21/1175 (1.8) | 14/1039 (1.3) | 22/1489 (1.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Catheter-associated UTIs | 50/586 (8.5) | 40/780 (5.1) | 167/2673 (6.2) | 87/1147 (7.6) | 67/1284 (5.2) | 192/3459 (5.6)§ | 40/952 (4.2) | 57/1416 (4.0) | 138/3171 (4.4) | 131/3959 (3.3) | 146/3905 (3.7) | 238/6357 (3.7) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| MRSA infections | 0/1348 | 1/2179 (<0.1) | 5/7629 (0.1) | 4/2653 (0.2) | 0/3190 | 4/9179 (<0.1) | 3/2728 (0.1) | 4/4612 (0.1) | 8/9808 (0.1) | 13/4776 (0.3) | 1/4793 (<0.1) | 9/7507 (0.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus | 0/1359 | 0/2219 | 0/7794 | 1/2678 (<0.1) | 0/3253 | 3/9383 (<0.1) | 0/2855 | 2/4861 (<0.1) | 10/10,384 (0.1) | 5/4802 (0.1) | 3/4834 (0.1) | 5/7574 (0.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Postoperative pneumonia | 4/151 (2.6) | 8/156 (5.1) | 28/334 (8.4)§ | 3/54 (5.6) | 3/27 (11.1) | 0/26 | 3/6 (50.0) | 1/10 (10.0) | 10/30 (33.3) | 107/4559 (2.3) | 99/4652 (2.1) | 237/7248 (3.3)‡ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 5/57 (8.8) | 7/78 (9.0) | 19/191 (9.9) | 3/21 (14.3) | 0/15 | 1/49 (2.0)§ | 8/50 (16.0) | 5/48 (10.4) | 24/193 (12.4) | 16/167 (9.6) | 11/167 (6.6) | 33/310 (10.6) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Postprocedural events | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with femoral-artery puncture for catheter-based angiographic procedures | 31/747 (4.1) | 22/967 (2.3) | 56/2586 (2.2)¶ | 2/165 (1.2) | 1/113 (0.9) | 6/359 (1.7) | 0/18 | 0/22 | 0/75 | 14/482 (2.9) | 4/363 (1.1) | 10/566 (1.8) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with hip replacement | 0/2 | 1/1 (100.0) | 2/3 (66.7) | NA | NA | 0/1 | NA | 0/2 | 0/3 | 43/826 (5.2) | 68/938 (7.2) | 164/1649 (9.9)‡ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Events associated with knee replacement | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 42/1254 (3.3) | 44/1336 (3.3) | 115/2158 (5.3)¶ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Contrast-induced nephropathy associated with catheter-based angiography | 75/744 (10.1) | 117/938 (12.5) | 354/2570 (13.8)¶ | 41/184 (22.3) | 16/103 (15.5) | 45/345 (13.0)¶ | 6/60 (10.0) | 3/19 (15.8) | 19/69 (27.5)§ | 116/528 (22.0) | 82/367 (22.3) | 169/577 (29.3)¶ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mechanical complications associated with central catheters | 9/241 (3.7) | 7/344 (2.0) | 27/965 (2.8) | 3/164 (1.8) | 8/171 (4.7) | 22/560 (3.9) | 15/341 (4.4) | 22/472 (4.7) | 64/1570 (4.1) | 38/1374 (2.8) | 25/1235 (2.0) | 64/1845 (3.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Postoperative cardiac events ∥ | 18/169 (10.7) | 4/169 (2.4) | 13/356 (3.7)¶ | 1/69 (1.4) | 0/29 | 1/31 (3.2) | 1/61 (1.6) | 0/37 | 5/74 (6.8) | 90/4712 (1.9) | 46/4764 (1.0) | 100/7460 (1.3)§ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Postoperative venous thromboembolic events | 0/169 | 0/169 | 1/356 (0.3) | 0/69 | 0/29 | 1/31 (3.2) | 1/61 (1.6) | 0/37 | 0/74 | 50/4712 (1.1) | 15/4764 (0.3) | 42/7460 (0.6)¶ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| All events | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall event rate | 513/10,976 (4.7) | 613/16,482 (3.7) | 1912/55,221 (3.5)‡ | 594/17,212 (3.5) | 526/20,077 (2.6) | 1642/58,335 (2.8)‡ | 623/18,397 (3.4) | 935/30,619 (3.1) | 2334/67,236 (3.5) | 1696/53,184 (3.2) | 1367/53,157 (2.6) | 2795/84,112 (3.3)§ |

|

| ||||||||||||

| ≥1 Event per hospitalization | 338/1360 (24.9) | 453/2223 (20.4) | 1420/7816 (18.2)‡ | 463/2689 (17.2) | 456/3268 (14.0) | 1375/9417 (14.6)¶ | 495/2889 (17.1) | 763/4900 (15.6) | 1832/10,480 (17.5) | 1041/4814 (21.6) | 956/4855 (19.7) | 1721/7594 (22.7) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| No. of events per 1000 hospitalizations** | 377.2 | 275.8 | 244.6‡ | 220.9 | 161.0 | 174.4‡ | 215.6 | 190.8 | 222.7§ | 352.3 | 281.6 | 368.1‡ |

IV denotes intravenous, LMW low-molecular-weight, MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, NA not available, and UTI urinary tract infection.

Data for 2007 and 2009 do not include data for 2008.

P<0.001 for linear trend from 2005–2006 to 2010–2011.

P<0.05 for linear trend from 2005–2006 to 2010–2011.

P<0.01 for linear trend from 2005–2006 to 2010–2011.

Postoperative cardiac events include events after cardiac and noncardiac surgeries.

If an adverse event could be counted more than once (e.g., some cases of postoperative pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia), only one was included in the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations.

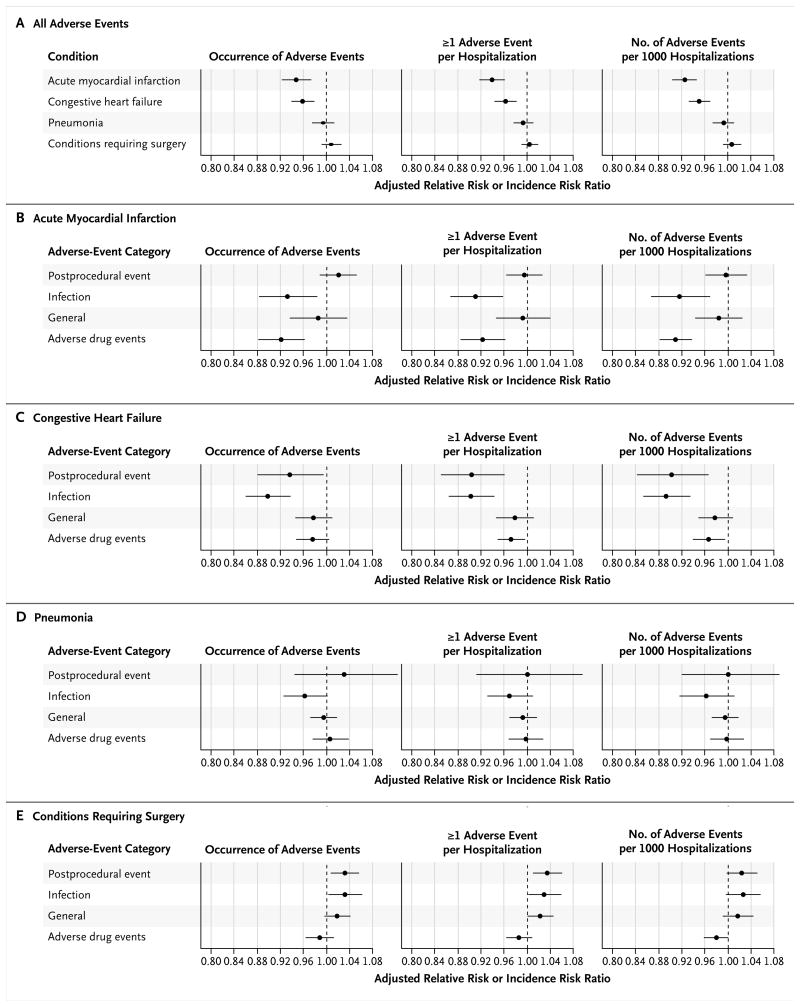

The findings did not change substantially when patient characteristics and geographic differences were taken into account. Among patients with acute myocardial infarction and those with congestive heart failure, respectively, the adjusted annual declines in the rate of occurrence of adverse events were 5.27% (95% CI, 2.70 to 7.77) and 4.02% (95% CI, 1.95 to 6.04), and the adjusted annual declines in the percentage of patients with one or more adverse events were 6.13% (95% CI, 3.86 to 8.36) and 3.68% (95% CI, 1.74 to 5.59). The adjusted annual declines in the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations were 7.55% (95% CI, 5.40 to 9.65) among patients with acute myocardial infarction and 4.84% (95% CI, 2.92 to 6.73) among patients with congestive heart failure. Adjusted adverse-event rates among patients with pneumonia showed slight declines and the rates among patients with conditions requiring surgery showed slight increases for all three outcomes; none of these changes were significant (Fig. 1A). When all four conditions were combined, the adjusted annual decline in the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations was 4.7% (95% CI, 3.7 to 5.6). The stratified analysis showed considerable variation in the trends of adverse-event rates across sex and racial subgroups (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 1. Adjusted Annual Changes in Adverse-Event Rates, Overall and According to Type of Adverse Event.

Panel A shows changes in overall adverse-event rates according to the condition, and Panels B through E show changes in rates for each condition according to the type of adverse event. The changes in the rate of occurrence of adverse events and in the proportion of patients with one or more adverse events are expressed as adjusted relative risk ratios for the ordinal time variable, ranging from 0 to 5, corresponding to year 2005 to year 2011 (except 2008). The change in the number of adverse events per 1000 hospitalizations is expressed as an adjusted incidence risk ratio for the ordinal time variable. A relative risk ratio or incidence risk ratio of less than 1.0 indicates a decline in adverse events over time. The horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

With respect to the type of adverse event, infection-related adverse events declined significantly for all three outcomes among patients with acute myocardial infarction and those with congestive heart failure. Drug-related adverse-event rates declined significantly among patients with acute myocardial infarction (all three outcomes) and among those with congestive heart failure (two of three outcomes); postprocedural adverse events improved substantially among patients with congestive heart failure (all three outcomes). However, rates of infection-related and postprocedural adverse events increased significantly among patients with conditions requiring surgery (Fig. 1E); surgical-site infections are not among the seven infection-related MPSMS measures.

Association of Adverse Events with In-Hospital Mortality and Length of Stay

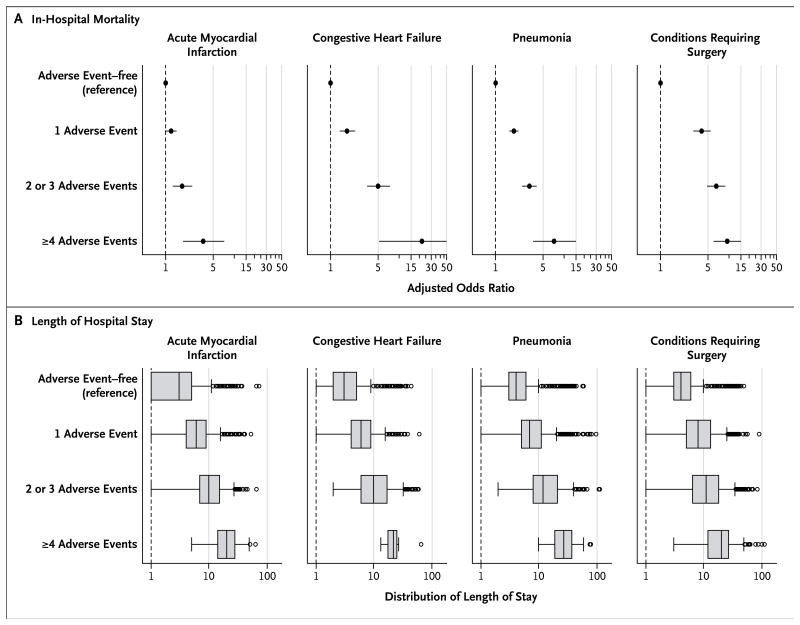

In 2010–2011, the observed mortality for patients who had one or more adverse events versus patients who did not have any adverse events was 11.0% versus 7.7% among patients with acute myocardial infarction, 6.7% versus 3.1% among those with congestive heart failure, 15.9% versus 7.4% among those with pneumonia, and 8.3% versus 1.0% among those with conditions requiring surgery (P<0.001 for all comparisons). This difference in mortality according to status with respect to adverse events did not change over the study period, despite significant reductions in in-hospital mortality and length of stay over time. The adjusted odds ratio for death among patients with one or more adverse events, as compared with patients with no adverse events, was 1.24 (95% CI, 1.01 to 1.51) for acute myocardial infarction, 1.77 (95% CI, 1.36 to 2.29) for congestive heart failure, 1.86 (95% CI, 1.60 to 2.16) for pneumonia, and 4.08 (95% CI, 3.06 to 5.44) for conditions requiring surgery. Figure 2A shows the adjusted odds of in-hospital death according to the number of adverse events. Patients who had adverse events also had significantly longer hospital stays than patients who did not have adverse events (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Association of Adverse Events with In-Hospital Mortality and Length of Stay, on the Basis of 2010–2011 Data.

The association between adverse events and in-hospital mortality (Panel A) is expressed as an adjusted odds ratio for each of the three dummy variables: one adverse event, two or three events, and four or more events, as compared with no adverse events. An odds ratio greater than 1 indicates that a patient with this characteristic is more likely to die during a hospitalization than a patient without any adverse events. The horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. The association between adverse events and length of stay (Panel B) is shown in box-and-whisker plots. The vertical line inside each box represents the median value; the left and right boundaries of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The left and right vertical lines outside each box (“whiskers”) represent the values that are 1.5 times below the 25th percentile and above the 75th percentile, respectively. The circles represent outliers.

Discussion

Patient safety is one of the top health care issues in the United States. In this study, we found that from 2005 to 2011, the in-hospital adverse-event rate declined significantly among patients with acute myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure for all three outcomes, but a similar reduction was not seen for patients with pneumonia and those with conditions requiring surgery. These declines might reflect overall national efforts to improve patient safety during the study period and secular trends in hospital quality-of-care improvements for acute myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure, because these conditions have been the focus of numerous national initiatives to improve care.18-20,22,23 Given the annual volume of approximately 350,000 and 750,000 hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure, respectively, among Medicare patients, these declines translate to approximately 81,000 in-hospital adverse events averted in 2010–2011 as compared with 2005–2006.

Although we found that adverse events, as a whole, declined significantly among patients with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure, several events — such as contrast-induced nephropathy, which has received little attention in patient-safety initiatives — increased significantly among patients with acute myocardial infarction, those with pneumonia, and those with conditions requiring surgery. In addition, there was no decline in ventilator-associated pneumonia (except in patients with congestive heart failure), and pressure ulcers increased in surgical patients and showed no significant change in medical patients, although both have received considerable national attention.

Although several measures to reduce surgical-site infections that are included in the Surgical Care Improvement Project and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program are not included in the MPSMS, our finding of an increased adverse-event rate among surgical patients indicates a continuing challenge and identifies an important target for patient-safety initiatives. Even though the mean age of patients with conditions requiring surgery was approximately 5 years younger than that of patients with congestive heart failure or acute myocardial infarction (75 vs. 80 years of age), an increasing number of elderly patients are undergoing surgical procedures. The volume of primary total knee arthroplasty increased by 161.5% from 1991 to 2010,33 and the number of mitral-valve surgeries performed in patients 84 years of age or older increased by 44% from 1999 to 2008.39

Our finding that there were substantial declines in adverse events among patients with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure extends the results of recent studies, which used different measurement approaches and did not target a specific medical condition. For example, Landrigan et al. reviewed 2341 admissions at 10 hospitals in North Carolina from 2002 to 2007 and found no significant changes in adverse events.24 Jain et al. found that the incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection declined by 62% from 2007 to 2010 at Veterans Affairs hospitals after a “MRSA bundle” was implemented in 2007.25 Downey et al. analyzed the inpatient claims data-base for the period from 1998 to 2007 on the basis of the AHRQ's 14 patient-safety indicators and reported that 7 indicators increased and 7 decreased.26 Our study represents a large and comprehensive investigation of national trends in patient safety for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, or conditions requiring surgery. The principal strengths of our work include the abstraction of data directly from medical records, the large number of patient-safety measures developed by national patient-safety experts in both the public and private sectors, and the use of the most recent national sample.

Our study has limitations that warrant discussion. First, the observed association between adverse events and longer hospital stays may simply reflect the greater opportunity for adverse events to develop during a longer stay. Second, we were unable to measure the daily risk of adverse events because the date of occurrence was missing for some events (Appendix D in the Supplementary Appendix). Third, since we focused on adverse events that were both detected and documented during the index hospitalization, we were unable to identify events that occurred but were not documented. Fourth, although we restricted our study sample to Medicare patients, a change in the sample design meant that from 2005 to 2009, data were representative of all patients discharged from acute-care hospitals, whereas from 2010 to 2011, approximately equal numbers of discharges were gathered from a random sample of acute-care hospitals. This latter sample may overrepresent patients discharged from smaller hospitals and may limit our ability to detect improvements over the study period. Other factors may also have affected our results. For example, more restrictive transfusion practices might have decreased our ability to detect anticoagulant-related events, and increasing attention to certain complications, such as Clostridium difficile infection, might have resulted in an increased frequency of testing and detection, independently of any change in actual rates.

In conclusion, from 2005 to 2011, rates of in-hospital adverse events declined significantly among patients with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure but not among patients with pneumonia or conditions requiring surgery. Although this suggests that national efforts focused on patient safety have made some inroads, the lack of reductions across the board is disappointing. We report these events to provide much-needed current and past data on the rates of adverse events and in the hope that future efforts to prevent patient harm will be increasingly effective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a contract from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Department of Health and Human Services (HHSA290201200003C), and a grant from the Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01HL105270-04, to Dr. Krumholz).

We thank all the previous and current Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System team members for their contributions to this work; Changqin Wang, M.D., and Behnood Bikdeli, M.D., from the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale–New Haven Hospital and Yale University, for their comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript; Sheila Eckenrode, R.N., C.P.H.Q., project manager at Qualidigm, for her leadership; and Anila Bakullari, B.S., research associate at Qualidigm, for her administrative support.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the official views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: what have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293:2384–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinton HR, Obama B. Making patient safety the centerpiece of medical liability reform. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2205–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher TH, Studdert D, Levinson W. Disclosing harmful medical errors to patients. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2713–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient safety challenge grants. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings.

- 7.Berwick DM, Calkins DR, McCannon CJ, Hackbarth AD. The 100,000 Lives Campaign: setting a goal and a deadline for improving health care quality. JAMA. 2006;295:324–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCannon CJ, Hackbarth AD, Griffin FA. Miles to go: an introduction to the 5 Million Lives Campaign. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:477–84. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-109publ41/html/PLAW-109publ41.htm.

- 10.The National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation Act. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-109s1784is/pdf/BILLS-109s1784is.pdf.

- 11.The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-109s1932enr/pdf/BILLS-109s1932enr.pdf.

- 12.Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ85/html/PLAW-110publ85.htm.

- 13.Smith SC, Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:216–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell TR, Jones RS. American College of Surgeons remains committed to patient safety. Am Surg. 2006;72:1005–9. 1021–30, 1133–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parry G, Cline A, Goldmann D. Deciphering harm measurement. JAMA. 2012;307:2155–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas EJ, Petersen LA. Measuring errors and adverse events in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:61–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krumholz HM, Radford MJ, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Aspirin in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in elderly Medicare beneficiaries: patterns of use and outcomes. Circulation. 1995;92:2841–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA. 1998;279:1351–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jencks SF, Huff ED, Cuerdon T. Change in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, 1998-1999 to 2000-2001. JAMA. 2003;289:305–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.305. Erratum, JAMA 2002;289:2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stulberg JJ, Delaney CP, Neuhauser DV, Aron DC, Fu P, Koroukian SM. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and the association with postoperative infections. JAMA. 2010;303:2479–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonow RO, Bennett S, Casey DE, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with chronic heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Heart Failure Clinical Performance Measures) endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1144–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Rumsfeld JS, et al. A call to ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network): a national effort to promote timely clinical feedback and support continuous quality improvement for acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:491–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.847145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2124–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1004404. Erratum, N Engl J Med 2010;363:2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain R, Kralovic SM, Evans ME, et al. Veterans Affairs initiative to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1419–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downey JR, Hernandez-Boussard T, Banka G, Morton JM. Is patient safety improving? National trends in patient safety indicators: 1998-2007. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:414–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levinson DR. Adverse events in hospitals: methods for identifying events. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General; Mar, 2010. Report no. OEI-06-08-00221 http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-08-00221.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg MD, Haviland AM, Yu H, Farley DO. Safety outcomes in the United States: trends and challenges in measurement. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:739–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Chen J, et al. Reduction in acute myocardial infarction mortality in the United States: risk-standardized mortality rates from 1995-2006. JAMA. 2009;302:767–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Normand SLT, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998-2008. JAMA. 2011;306:1669–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh RW, Normand SLT, Wang Y, Barr CD, Dominici F. Geographic disparities in the incidence and outcomes of hospitalized myocardial infarction: does a rising tide lift all boats? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:197–204. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.962456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA. 2012;307:1405–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308:1227–36. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt DR, Verzier N, Abend SL, et al. Fundamentals of Medicare patient safety surveillance: intent, relevance and transparency. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/advances/vol2/Hunt.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huddleston JI, Maloney WJ, Wang Y, Verzier N, Hunt DR, Herndon JH. Adverse events after total knee arthroplasty: a national Medicare study. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(Suppl):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metersky ML, Hunt DR, Kliman R, et al. Racial disparities in the frequency of patient safety events: results from the National Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System. Med Care. 2011;49:504–10. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fc218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyder CH, Wang Y, Metersky ML, et al. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: results from the national Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1603–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodson JA, Wang Y, Desai MM, et al. Outcomes for mitral valve surgery among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 1999 to 2008. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:298–307. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.