Abstract

Cardiovascular adjustments to exercise are partially mediated by group III/IV (small to medium) muscle afferents comprising the exercise pressor reflex (EPR). However, this reflex can be inappropriately activated in disease states (e.g., peripheral vascular disease), leading to increased risk of myocardial infarction. Here we investigate the voltage-dependent calcium (CaV) channels expressed in small to medium muscle afferent neurons as a first step toward determining their potential role in controlling the EPR. Using specific blockers and 5 mM Ba2+ as the charge carrier, we found the major calcium channel types to be CaV2.2 (N-type) > CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) > CaV1.2 (L-type). Surprisingly, the CaV2.3 channel (R-type) blocker SNX482 was without effect. However, R-type currents are more prominent when recorded in Ca2+ (Liang and Elmslie 2001). We reexamined the channel types using 10 mM Ca2+ as the charge carrier, but results were similar to those in Ba2+. SNX482 was without effect even though ∼27% of the current was blocker insensitive. Using multiple methods, we demonstrate that CaV2.3 channels are functionally expressed in muscle afferent neurons. Finally, ATP is an important modulator of the EPR, and we examined the effect on CaV currents. ATP reduced CaV current primarily via G protein βγ-mediated inhibition of CaV2.2 channels. We conclude that small to medium muscle afferent neurons primarily express CaV2.2 > CaV2.1 ≥ CaV2.3 > CaV1.2 channels. As with chronic pain, CaV2.2 channel blockers may be useful in controlling inappropriate activation of the EPR.

Keywords: CaV2.2, CaV2.1, CaV2.3, dorsal root ganglia neurons, exercise pressor reflex

the group i (aα) and ii (Aβ) muscle afferents provide sensory information needed to guide motor activity (Houk 1974). The group III (Aδ) and IV (C) afferents transmit muscle pain signals and also mediate the exercise pressor reflex (EPR) (Kaufman and Hayes 2002), which is a critical neural mechanism that regulates the cardiovascular response to exercise (Kaufman and Hayes 2002). This reflex is clinically important because certain diseases, such as peripheral vascular disease and heart failure, can produce muscle ischemia that drives EPR activity, which can generate additional cardiac stress to increase the risk of myocardial infarction (Baccelli et al. 1999; Bakke et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2006). Here we investigate the voltage-dependent calcium (CaV) channels expressed in muscle afferent neurons as an initial step in understanding the role of these channels in controlling excitability of neurons that mediate the EPR.

CaV channels play a prominent role in neuronal excitability (Khosravani and Zamponi 2006). At synaptic terminals, they deliver the Ca2+ needed to induce the release of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters (Lisman et al. 2007). There are 10 genes that encode CaV channels (Catterall et al. 2005). In dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons, the evidence supports the expression of L-type (CaV1.2), P/Q-type (CaV2.1), N-type (CaV2.2), R-type (CaV2.3, also called E-type or α1E), and T-type (CaV3.2) (Vanegas and Schaible 2000; Zamponi et al. 2009). The importance of CaV2.2 channels in chronic pain has been highlighted by the success of the specific blocker ziconotide (SNX-111 or ω-conotoxin MVIIA) in the treatment of chronic pain in many patients (Elmslie 2004; Molinski et al. 2009). This intrathecally delivered drug blocks transmission from primary to secondary nociceptors by blocking presynaptic CaV2.2 channels (Motin and Adams 2008). While the effect of blocking presynaptic CaV channels is to reduce central nervous system excitability, blocking CaV channels can also increase neuronal excitability through reduced activation of closely associated Ca2+-activated potassium channels (Marrion and Tavalin 1998; Yu et al. 2010). Indeed, blocking CaV channels increases excitability of sensory neurons (Lirk et al. 2008). Thus it is important that we understand the CaV channels expressed in muscle afferent neurons, along with the modulation of these channels by molecular activators of the EPR. ATP is one of these activators, which works by acting on P2X receptors (Cui et al. 2011; Hayes et al. 2008). However, ATP can inhibit CaV channels by activation of G protein-coupled P2Y receptors (Filippov et al. 2003; Gerevich et al. 2004). Here we identify the CaV channels that are functionally expressed by muscle afferent neurons and show that ATP can inhibit the CaV current by reducing activity of CaV2.2 (N-type) channels. As with chronic pain, we show that CaV2.2 channels could be an important target for the treatment of symptoms resulting from excessive EPR activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of muscle afferent neurons.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight 150–400 g) were obtained from Hill Top Laboratories (Scottdale, PA). All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. The labeling and neuronal isolation followed previously described procedures (Ramachandra et al. 2012). Briefly, muscle afferent neurons were labeled by retrograde transport of the lipophilic dye DiI (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate) [100 μl of 1.5% DiI in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] that was injected into both left and right gastrocnemius muscles of anesthetized rats (ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine). Four to five days postinjection, the rats were killed with CO2 followed by decapitation. Neurons from the lumbar DRG L4 and L5 were isolated using an enzyme mixture of trypsin, collagenase, and DNAse and plated onto polylysine-coated glass coverslips. The isolated neurons were maintained overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in minimal essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Expressed CaV channels.

CaV2.3 channels (α1, β2A, and α2δ cDNA constructs, generous gifts from Dr. Henry L. Puhl, National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism) were heterologously expressed in LN229 cells by intranuclear microinjection at a ratio of 1:1:2. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Following cDNA injection, the cells were incubated overnight, and electrophysiological recordings were performed the next day.

Solutions.

Most DiI-positive DRG neurons were initially recorded in an external solution containing (in mM) 45 NaCl, 100 N-methyl d-glucosamine (NMG)·Cl, 4 MnCl2, 10 Na·HEPES, 10 glucose, and 0.0003 tetrodotoxin (TTX), with pH = 7.4 and osmolarity = 320 mosM, which was used to identify voltage-gated sodium (NaV) 1.8 expressing muscle afferent neurons (Ramachandra et al. 2012). When recording CaV current, the external solution was switched to a barium external solution containing (in mM) 145 NMG·Cl, 5 BaCl2, 10 NMG·HEPES, and 5 glucose, with pH = 7.4 and osmolarity = 320 mosM. The pipet solution contained (in mM) 104 NMG·Cl, 14 creatine·PO4, 6 MgCl2, 10 NMG·HEPES, 5 Tris·ATP, 10 NMG2·EGTA, and 0.3 Tris2·GTP, with pH 7.4 and osmolarity = 300 mosM.

For some experiments, the CaV currents in muscle afferent neurons were recorded in external Ca2+. NaV1.8 expressing muscle afferents were identified by expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein (Puhl and Ikeda 2008), as previously described (Hassan and Ruiz-Velasco 2013). Briefly, DRG neurons were microinjected with a cDNA plasmid containing the enhanced green fluorescent protein gene under control of the putative NaV1.8 promoter. The external solution for these experiments contained (in mM) 145 tetraethanolamine (TEA)·CH3SO3H, 10 TEA·HEPES, 10 CaCl2, 15 glucose, and 0.0003 TTX, pH 7.4, 325 mosM. The internal solution contained (in mM) 90 NMG·CH3SO3H, 25 TEA·CH3SO3H, 14 creatine·PO4, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, 20 CsOH, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, pH 7.2, 300 mosM. The expressed CaV2.3 channels were recorded in a solution containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 10 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with NaOH. The internal solution was the same as that used for muscle afferent neurons recorded in Ca2+.

Ion channel blockers were made up as stock solutions in either water or DMSO and diluted into the external solution to make the working concentration. All external solutions contained the same DMSO concentration (maximum 0.03%) so that the only change was presence or absence of the blocker. In experiments where Ca2+ was the charge carrier, 0.1 mg/ml cytochrome c was added to all external solutions to minimize potential binding of the peptide toxins to the capillary columns used for drug delivery. Solutions were applied using a gravity fed perfusion system with a solution exchange time of 2 s.

Measurement of ionic currents.

DiI-labeled DRG neurons were identified using a Nikon Diaphot microscope with epifluorescence and voltage-clamped using the whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Pipettes were pulled from glass capillaries (King Precision Glass, Claremont, CA) on a Sutter P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Currents were recorded using either an Axopatch 200A or 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and digitized with an ITC-18 data acquisition interface (Instrutech, Port Washington, NY). Experiments were controlled using S5 data acquisition software written by Dr. Stephen Ikeda (NIH/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Rockville, MD). Leak current was subtracted online using a P/4 protocol. Recordings were carried out at room temperature, and the holding potential was −80 mV.

Data analysis.

Data were analyzed using IgorPro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) running on a Macintosh computer. Cell diameter was calculated using the cell capacitance as previously described (Ramachandra et al. 2012). Group data were calculated as means ± SD throughout the paper. Student's T-test (unpaired, two-tailed) was calculated to determine significant differences (P < 0.05).

Immunocytochemistry.

Neurons were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 2% Tween 20, as previously described (Ramachandra et al. 2012). Neurons were labeled with primary antibodies for both NaV1.8 (mouse, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and CaV2.3 (rabbit, Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel) (1:500) and visualized using secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 IgG goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 635 IgG goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Images were captured using a Nikon ECLIPSE 80i epifluorescence microscope, and neurons were measured using ImageJ (rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html). Cell size was calculated and positive fluorescent labeling was determined, as described previously (Ramachandra et al. 2012).

Chemicals.

DiI, minimal essential medium, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, FBS, and penicillin/streptomycin were obtained from Invitrogen. TTX citrate, nifedipine (Nif), and SNX482 (SNX) were obtained from Ascent Scientific (Princeton, NJ). ω-Conotoxin GVIA (GVIA) and ω-agatoxin IVa (AgaIVa) were obtained from Bachem America (King of Prussia, PA). All other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

We were interested in determining the CaV channels that are functionally expressed in muscle afferent neurons. Consistent with previous work, we used pharmacology to determine the percentage of total CaV current generated by each channel type. CaV2.2 (N-type) was determined from block by 10 μM GVIA, CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) from block by 0.2 μM AgaIVa, CaV1.2 from block by 3 μM Nif and CaV2.3 (R-type) from block by 0.3 μM SNX (Fuchs et al. 2007; Huang et al. 1997; Ikeda and Matsumoto 2003; Lu et al. 2010; Ohnami et al. 2011). Using our 5 mM Ba2+ external solution, we found that the largest block was produced by GVIA (47 ± 19%, n = 20) > AgaIVa (25 ± 14%, n = 16) > Nif (13 ± 14%, n = 16) (Fig. 1). The block produced by each of these three drugs was significant (P < 0.05). However, SNX produced no significant block (−7 ± 11%, n = 6). This was surprising since previous work had shown SNX-sensitive currents in DRG neurons (Fang et al. 2007; Fuchs et al. 2007). Perhaps muscle afferent neurons fail to express CaV2.3 channels. However, 22 ± 16% (P < 0.05, n = 11) of the total CaV current was resistant to all blockers (resistant current). As expected, only block by GVIA was irreversible (Boland et al. 1994; Liang and Elmslie 2002).

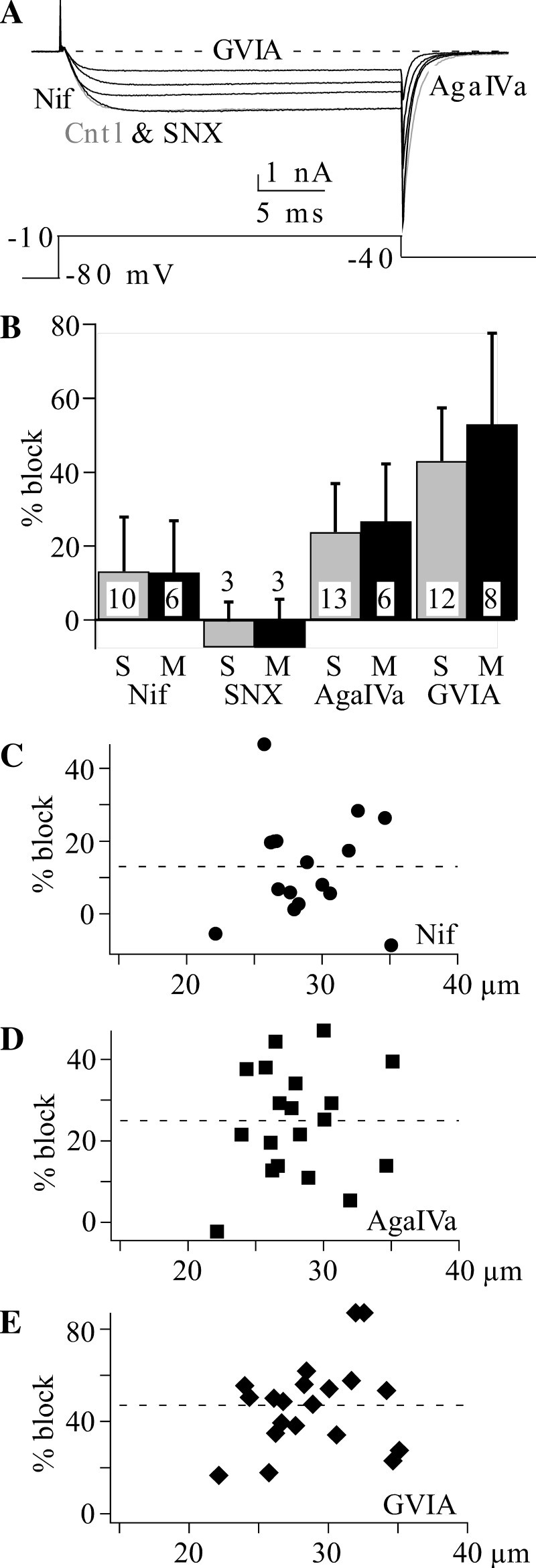

Fig. 1.

Voltage-dependent calcium (CaV) 2.2 channels generate the dominant CaV current in muscle afferent neurons. CaV current in 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) labeled muscle afferent neurons was measured using 5 mM Ba2+ external solution. A: example currents showing the effect of 0.3 μM SNX482 (SNX), 0.2 μM ω-agatoxin IVa (AgaIVa), 3 μM nifedipine (Nif), and 10 μM ω-conotoxin GVIA (GVIA). The voltage protocol is shown below the current traces. Cntl, control. B: comparison of mean ± SD calcium current block in small (S; 20–30 μm) vs. medium (M; 30–40 μm) muscle afferent neurons by the indicated blockers. The blocker concentrations are the same as indicated for A. C–E: the distribution of percentage block vs. neuron diameter for 3 μM Nif (C), 0.2 μM AgaIVa (D), and 10 μM GVIA (E). Note the different y-axis scale for GVIA. The dashed line indicates average block.

Previous work has shown differences in the percentage CaV current blocked by various specific blockers in small vs. medium or large DRG neurons (Fuchs et al. 2007; Scroggs and Fox 1992). Thus it appears that expression of CaV channel types can vary across classes of DRG neurons. Unmyelinated C-type and thinly myelinated Aδ-type cutaneous afferents have cell body diameters < 35 μm, with C fibers having diameters < 23 μm (Djouhri et al. 2003). However, muscle afferents were found to have larger soma diameters relative to cutaneous afferents (Hu and McLachlan 2003; Ramachandra et al. 2012). Thus we include muscle afferent neurons up to 40 μm in the group III (Aδ) and define small group IV (C) afferent neurons as those with cell diameters < 30 μm (Ramachandra et al. 2012, 2013). While the CaV current was significantly blocked by Nif, AgaIVa, and GVIA (but not SNX) in both groups, we found no differences in percentage block by any CaV channel blocker between small and medium neurons (Fig. 1B), which is consistent with previous findings from cutaneous afferents (Lu et al. 2010). In addition, the resistant current was not different between these two groups at 21 ± 12% (n = 7) of total CaV current in small neurons and 25 ± 24% (n = 4) in medium neurons. A more detailed examination of the CaV channel block data is shown using scatter plots (Fig. 1, C–E), which shows that there are no systematic differences among muscle afferent neurons ranging from 20 to 40 μm diameter. Thus neurons in both the group III (Aδ) and group IV (C) size range most prominently express CaV2.2 > CaV2.1 > CaV1.2 (Fig. 1).

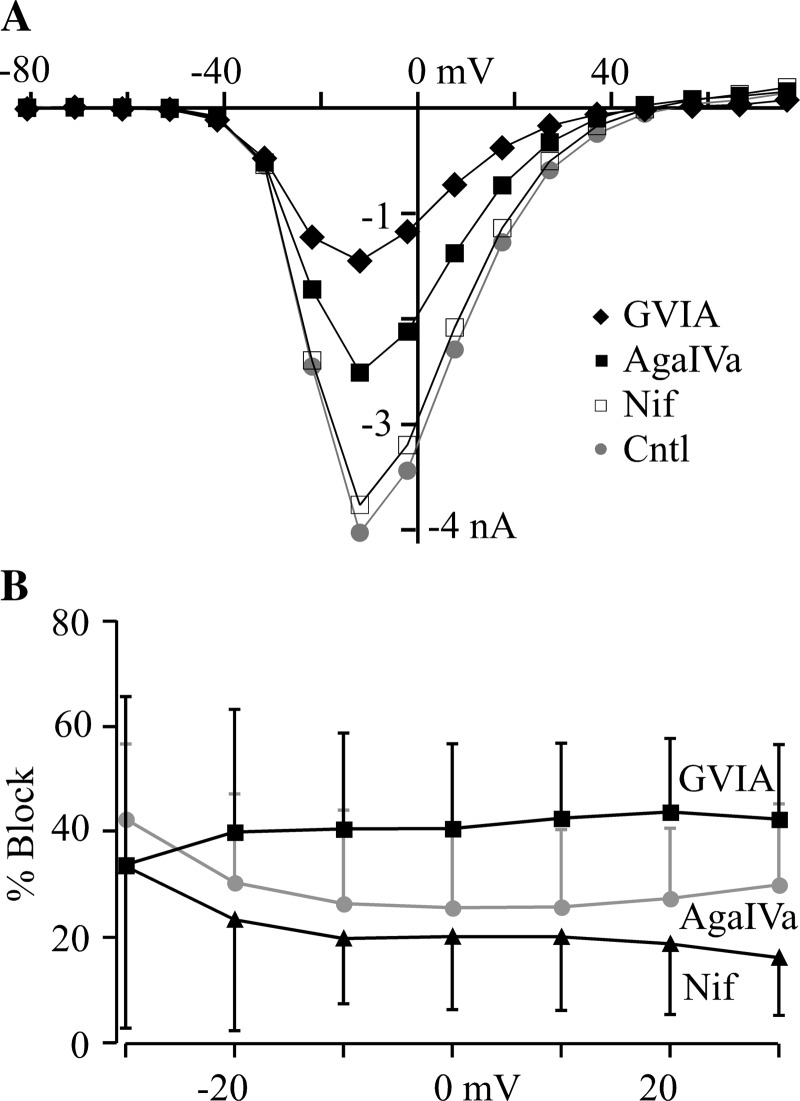

The functional expression of CaV3 (T-type) channels in DRG neurons has been demonstrated (Ikeda and Matsumoto 2003; Jagodic et al. 2008; Scroggs and Fox 1992), but we failed to observe evidence of CaV3 currents in our recordings in Ba2+. Such currents are characterized by low-voltage activation (less than −30 mV) and rapid inactivation (Scroggs and Fox 1992). To quantitatively determine whether CaV3 currents contributed to the total CaV current, we calculated the percentage inhibition over a range of voltages for each of the three blockers that produced significant inhibitions. CaV3 currents would be revealed by the relatively smaller block at hyperpolarized voltages where CaV3 channels dominate (Ikeda and Matsumoto 2003; Jagodic et al. 2008; Scroggs and Fox 1992). Using our standard holding potential (−80 mV), we found no significant difference in the inhibition at −30 vs. +30 mV produced by any of our blockers (Fig. 2). It was not possible to do this analysis using more hyperpolarized voltages, since −30 mV was the most hyperpolarized voltage to produce measureable current. Under these conditions, it appears that CaV3 channels do not significantly contribute to total CaV current in muscle afferent neurons.

Fig. 2.

Voltage-independent block by CaV channel blockers. A: current-voltage relationships from a muscle afferent neuron in the presence of either 3 μM Nif, 0.2 μM AgaIVa, or 10 μM GVIA. CaV currents were measured in 5 mM Ba2+ at the end of 25-ms voltage steps to the indicated voltage. B: the mean inhibition (±SD) for each CaV channel blocker is shown over voltages ranging from −30 to 30 mV. The currents were measured as described for A. There was no statistical difference between the block at −30 mV vs. that at 30 mV for each blocker (n = 5 for each blocker).

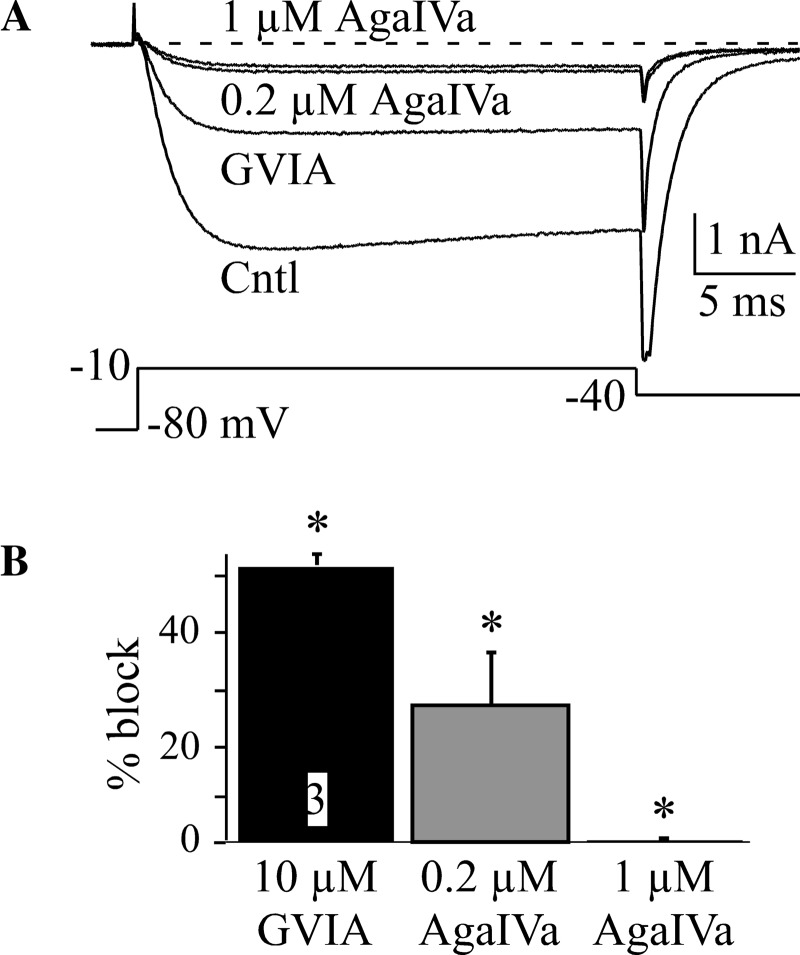

CaV2.1 (P/Q) currents are typically blocked using submicromolar concentrations of AgaIVa (Fuchs et al. 2007; Huang et al. 1997), since CaV2.2 channels have been shown to be blocked by 1 μM AgaIVa (Sidach and Mintz 2000). However, Q-currents are a CaV2.1 isoform that is less sensitive to AgaIVa block and is typically blocked using micromolar AgaIVa concentrations (Randall and Tsien 1995; Sidach and Mintz 2000). We wondered if a component of our resistant current (22% of total CaV current) was contributed by Q-channels. Therefore, we compared block of muscle afferent CaV current in 0.2 vs. 1 μM AgaIVa after block by GVIA to remove the CaV2.2 component (Fig. 3). In these neurons, GVIA blocked 50 ± 2% of current, and 0.2 μM AgaIVa blocked 26 ± 9% of current, but increasing AgaIVa to 1 μM blocked only an additional 4 ± 1% of current. Thus a weakly AgaIVa-sensitive CaV2.1 channel type (e.g., Q-current) does not substantially contribute to resistant current in muscle afferent neurons.

Fig. 3.

Little or no Q-current in muscle afferent neurons. CaV current from muscle afferent neurons was recorded in 5 mM Ba2+ external solution. A: example currents from a muscle afferent neuron in Cntl, 10 μM GVIA, 0.2 μM AgaIVa, and 1 μM AgaIVa. B: the mean (±SD) percentage block by GVIA and the two concentrations of AgaIVa tested on the same neurons. The number of cells tested is indicated in the GVIA bar. *CaV current was significantly blocked.

The absence of SNX-sensitive CaV current was puzzling. We wondered if our use of Ba2+ as the charge carrier was the problem, since it was previously demonstrated that R-like CaV current was enhanced when Ca2+ was the charge carrier (Boland et al. 1994; Liang and Elmslie 2001). Using the same blockers, we redid our study using a 10 mM Ca2+ external solution. In addition, we used a cumulative blocker application strategy to better gauge the resistant current (Fig. 4). It should be noted that, under these recording conditions (HP −80 mV), we observed T-type currents, but only in ∼10% of muscle afferent neurons. The percentage block by Nif, GVIA, and SNX was statistically similar (P > 0.05) to that in Ba2+, and the resistant current was also similar between Ca2+ and Ba2+ (P > 0.05). However, the block by AgaIVa was smaller in Ca2+ (13 ± 2%) vs. Ba2+ (25 ± 14%). We do not understand the reasons for the smaller AgaIVa block in Ca2+, but it is clear that Ca2+ did not enhance SNX-sensitive current, as we predicted.

Fig. 4.

CaV current block in external Ca2+ is similar to that in Ba2+. A: an example time course for CaV current block in 10 mM external Ca2+. This experiment utilized cumulative blocker application to better determine the size of the resistant current (Resistant). The blocker concentrations are indicated and were the same as those used when recording in external Ba2+. B: the average (±SD) percentage block by each CaV channel blocker. *CaV current was significantly blocked. The number of cells tested is indicated in each bar.

As a positive control for SNX, we tested 0.3 μM SNX on CaV2.3 channels heterologously expressed in LN229 cells. The recordings were done using a 10 mM Ca2+ external solution, and SNX blocked 93 ± 8% (n = 3) of the expressed current. Thus two possible explanations for the absence of a SNX effect on muscle afferent neurons are that CaV2.3 channels are not expressed by these neurons, or the expressed CaV2.3 channels are insensitive to SNX.

CaV2.3 in muscle afferent neurons.

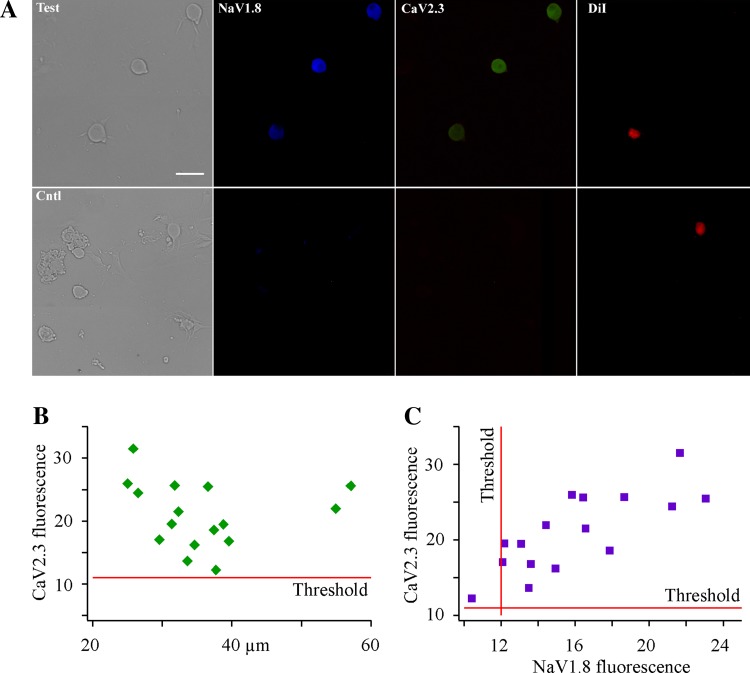

SNX has been used in many experiments to define CaV2.3 current, but not all CaV2.3 channels are sensitive to SNX (Tottene et al. 2000). To determine whether CaV2.3 channels were expressed in muscle afferent neurons, we exposed isolated DRG neurons to a rabbit CaV2.3 antibody. For consistency with our electrophysiological recordings, we also tested for the presence of NaV1.8 using a specific mouse antibody. We found that all muscle afferent neurons were positively labeled by the CaV2.3 antibody (Fig. 5, A and B), and all but one of these neurons were also labeled by the NaV1.8 antibody (Fig. 5C). Most of the identified muscle afferent neurons had soma diameters between 20 and 40 μm, which overlaps with the electrophysiological recordings. Thus muscle afferent neurons appear to express CaV2.3 channels.

Fig. 5.

Immunocytochemistry shows CaV2.3 channels expressed in muscle afferent neurons. A: the upper four images show sensory neurons stained with both voltage-gated sodium (NaV) 1.8 and CaV2.3 antibodies. The bright-field (left) image shows the three neurons, and the DiI panel (right) shows the one labeled muscle afferent neuron in this field. All three neurons were positive for both NaV1.8 and CaV2.3. The white bar in the bright-field image indicates 50 μm. The lower four images show NaV1.8 and CaV2.3 controls along with bright-field (left) image and the DiI image showing one labeled muscle afferent neuron. B: there is no correlation between CaV2.3 label intensity and muscle afferent neuron size. The threshold line was determined from measurement of Cntl muscle afferent neurons (e.g., lower images in A). The units for the Y-axis are arbitrary fluorescence units. C: comparison of CaV2.3 label intensity vs. that of NaV1.8 in muscle afferent neurons. The threshold lines were determined from Cntl muscle afferent neurons. Only one CaV2.3-positive muscle afferent neuron was negative for NaV1.8.

We also wanted to test if these channels were functional, but our blocker (SNX) did not work. One strategy was to use roscovitine, which is a CaV2-specific agonist (Buraei et al. 2005, 2007). While roscovitine affects many ion channels (Buraei et al. 2007; Ganapathi et al. 2009; Yarotskyy and Elmslie 2007, 2012), it uniquely affects CaV2 channels by slowing deactivation (Buraei et al. 2005, 2007), which produces slow tail currents (Fig. 6). For these experiments, we tested the effect of 100 μM roscovitine after blocking CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 with 0.2 μM AgaIVa and 10 μM GVIA, respectively. Figure 6A shows the effect of roscovitine to inhibit step current and slow deactivation of total CaV current (before block of CaV2.1 and 2.2). After toxin application, the tail current is still reversibly slowed by roscovitine (Fig. 6, B and C). The roscovitine-induced inhibition was similar before and after applications of the toxins, with average reductions of 39 ± 15% and 52 ± 18% for control and in toxins, respectively. The slowed deactivation shows that functional CaV2 channels produce current in the presence of AgaIVa and GVIA. The similar inhibition before and after toxin application suggests that roscovitine did not reverse toxin block to reveal CaV2.2 or 2.1 channels, which would have been caused either by an increase in step current or a decrease in inhibition. The most likely conclusion is that SNX-resistant CaV2.3 channels comprise a large fraction of the resistant CaV current in small to medium muscle afferent neurons.

Fig. 6.

Roscovitine (Rosc)-induced slowed deactivation reveals functional CaV2 channels in the presence of GVIA and AgaIVa. All currents were recorded in 5 mM Ba2+. A: a muscle afferent neuron shows the effect of Rosc on CaV2 currents (no toxins present). Rosc (100 μM) slowed deactivation (black trace) compared with Cntl and recovery (Recov; gray traces). B: current traces from the same muscle afferent neuron as shown in A recorded in 10 μM GVIA and 0.2 μM AgaIVa. Rosc (100 μM) (black trace) slowed deactivation compared with Cntl (Toxin) and Recov (gray traces). C: a single exponential equation was fit to the deactivating currents at −40 mV to determine the deactivation τ in presence of toxin (GVIA and AgaIVa) and toxin + 100 μM Rosc. The average deactivation τ (±SD) is shown. *Significant slowing of deactivation induced by Rosc. The number of muscle afferent neurons tested is indicated in the middle bar.

As a second test, we examined the Ni2+ sensitivity of the resistant current. It has been demonstrated in major pelvic ganglion neurons that SNX-resistant R-current is blocked by Ni2+ with an IC50 (22 μM) similar to that of expressed CaV2.3 channels (21 μM) (Won et al. 2006). Using Ba2+ as the charge carrier, we tested the dose response for Ni2+ block of total CaV current and calculated an IC50 = 246 μM (n = 3–4 neurons), which is expected for CaV currents dominated by CaV2.2 and 2.1 channels (Liang and Elmslie 2001; Zamponi et al. 1996). However, following application of 1 μM GVIA to block the dominant CaV2.2 current, the Ni2+ block IC50 did not change with IC50 = 319 μM (n = 7–8 neurons), which was against our expectation of a decrease in IC50. It has been previously reported that the Ni2+ sensitivity of CaV2.3 current was ∼300 μM when recorded in 10 mM Ba2+, but < 30 μM when recorded in 10 mM Ca2+ (Zamponi et al. 1996). In addition, the Ni2+-sensitive R-current of major pelvic ganglion neurons was recorded in 10 mM Ca2+ (Won et al. 2006). Therefore, we reexamined the Ni2+ block of CaV currents recorded in 10 mM Ca2+. We found that the Ni2+ block of the resistant current (Nif, GVIA, and AgaIVa) recorded in Ca2+ was much more potent than when recorded in Ba2+ with IC50 = 4.4 μM (n = 2 to 5) and the maximum block = 64%. The potent Ni2+ block suggests that the majority of the resistant current (64%) was generated by the activity of CaV2.3 channels.

ATP modulates CaV2.2 channels.

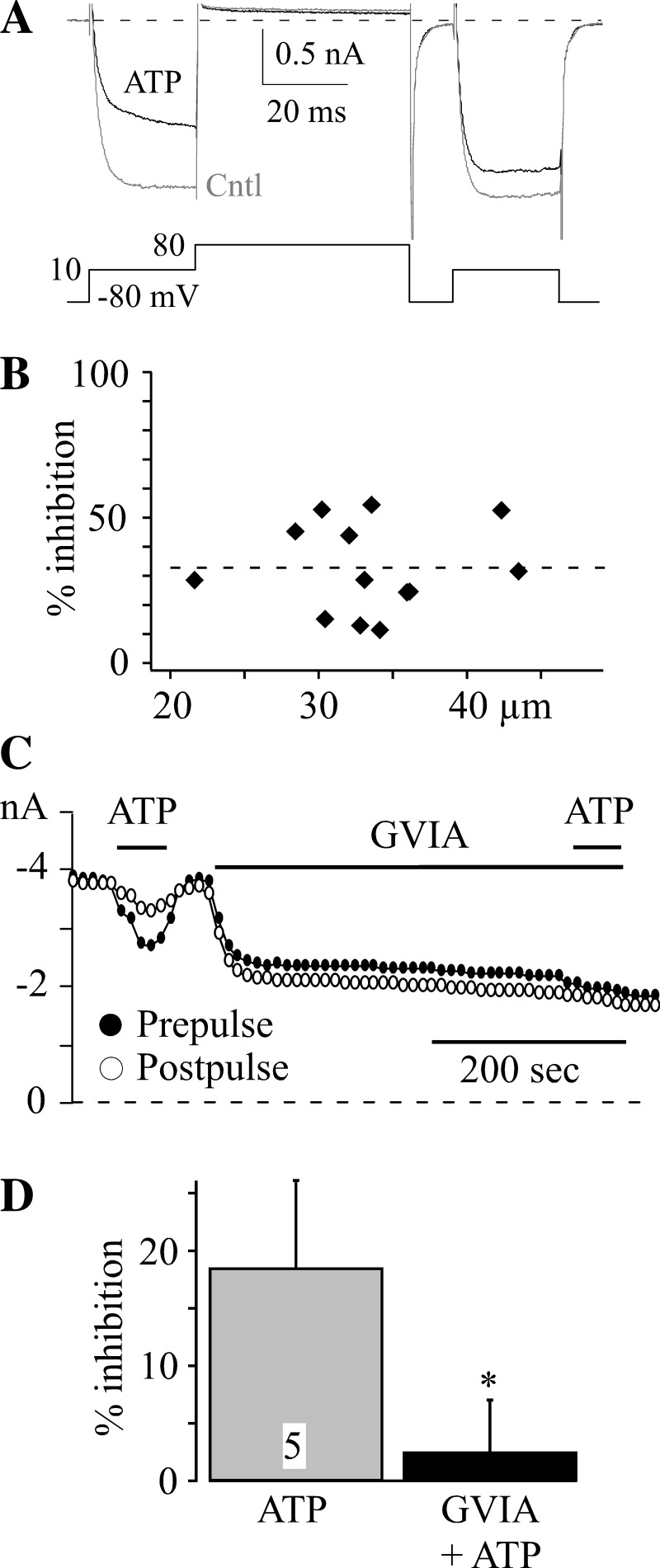

ATP helps to generate the EPR by activating P2X ionotropic receptors (Cui et al. 2011; Hayes et al. 2008), but ATP modulation of the reflex is also possible by activation of G protein-coupled P2Y receptors. ATP has been shown to inhibit CaV currents by activation of P2Y receptors (Filippov et al. 2003; Gerevich et al. 2004), so we tested the effect on muscle afferent CaV currents (Fig. 7). G protein-mediated inhibition of CaV2 currents is often found to be voltage dependent in that the inhibition is temporarily reversed by brief, strong depolarization (Elmslie et al. 1990; Ikeda 1991). ATP (10 μM) produced an average 32 ± 15% (n = 13) (Fig. 7B) inhibition of CaV current that was reversed following strong depolarization (Fig. 7A). In addition, there was no clear difference in the percentage inhibition observed among neurons with diameters ranging from 22 to 48 μm (Fig. 7B). Previous reports have demonstrated CaV2.2 (N-type) to be a major target of G protein-mediated inhibition (Elmslie et al. 1990; Gerevich et al. 2004; Ikeda 1991), but other CaV2 channels can be modulated as well (Colecraft et al. 2000; Meza and Adams 1998). Thus we determined the effect of GVIA on ATP modulation (Fig. 7D). Prior to GVIA application, ATP inhibited current (prepulse) by an average of 19 ± 8%, while the inhibition was reduced to an average of 3 ± 4% following GVIA block of CaV2.2 channels in the same five neurons. CaV2.2 channels are the primary CaV channel target for ATP-induced inhibition in muscle afferent neurons.

Fig. 7.

ATP inhibits CaV2.2 channels in muscle afferent neurons. All currents were recorded in 10 mM Ca2+. A: the inhibition of CaV current induced by 10 μM ATP (black trace) compared with Cntl (gray trace) recorded from a muscle afferent neuron. The inhibition is transiently reversed by strong depolarization (+80 mV), which can be seen by comparing the prepulse (before the +80-mV step) and postpulse (following the +80-mV step) currents. B: there was no clear differences in ATP (10 μM) induced inhibition in small (<30 μm) vs. medium (30–40 μm) vs. large (>40 μm) muscle afferent neurons. The percent inhibition of prepulse current measured from 13 muscle afferent neurons is plotted vs. neuron diameter. C: the ATP (10 μM) inhibition is blocked by preapplication of 10 μM GVIA. This time course shows the inhibition induced by ATP prior to GVIA application and little or no ATP response in the presence of GVIA. The prepulse (solid circle) and postpulse (open circle) current amplitudes are plotted. D: the average (±SD) inhibition induced by 10 μM ATP is shown before (ATP) and during (GVIA + ATP) application of 10 μM GVIA. *ATP response in GVIA is significantly different from that in Cntl. The number of muscle afferent neurons tested is indicated.

DISCUSSION

We have identified the CaV channels that generate CaV current in muscle afferent neurons along with examining the modulation of that current by ATP. The results demonstrate that, regardless of using external Ba2+ or Ca2+, CaV2.2 channels dominate by generating 40–50% of the total CaV current. CaV2.1 channels generated between 13 and 25% of the current, while CaV1.2 channels generated ∼15% of the total current. The CaV2.3 channel blocker SNX had no effect on muscle afferent CaV current, while the portion of the current that was resistant to all blockers averaged ∼25% of the total current. Using roscovitine and Ni2+, we demonstrated that the majority of resistant current is generated by CaV2.3, which shows that the current generated by this channel type is roughly equal to that generated by CaV2.1. In the small to medium neurons recorded in our study, there was no difference in CaV channel expression between these two groups. ATP inhibited CaV current by activation of G protein-coupled receptors, and that inhibition primarily targeted CaV2.2 channels. Based on the neuronal size and the expression of NaV1.8 by these neurons (Ramachandra et al. 2012), we conclude that group IV (C) and group III (Aδ) neurons primarily express CaV2.2 channels that are inhibited by extracellular ATP.

CaV channels in sensory neurons.

The percentage of CaV channel types comprising the total current in our work matches well with most studies on small- and medium-diameter sensory neurons with CaV2.2 > CaV2.1 = CaV2.3 > CaV1.2 (Huang et al. 1997; Lu et al. 2010). However, Scroggs and Fox (1992) found a much larger block by 2 μM nimodipine (53%) in small sensory neurons (20–27 μm) and a much smaller block (7%) in medium-sized neurons (33–38 μm) than we and others have observed. The source of this difference is unclear, but it is possible that there is a population of DRG neurons in which CaV1.2 channels dominate.

One important issue when using blockers to identify component channels is the specificity and concentration of the chosen compounds. The blockers used in this study were the same as used in many previous studies. GVIA is a highly specific blocker of CaV2.2 channels, but the concentration we used was higher than some other studies (Fuchs et al. 2007; Huang et al. 1997; Lu et al. 2010; Scroggs and Fox 1992). Early studies of CaV2.3 showed this channel was reversibly blocked by 5 μM GVIA when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Zhang et al. 1993), but we did not observe a reversible component to the GVIA block in our studies. In addition, GVIA has been shown to be specific for CaV2.2 in neurons at concentrations up to 100 μM (Boland et al. 1994; Elmslie 1997). Finally, the percentage CaV current blocked by GVIA in our study was similar to that in studies using lower concentrations (Huang et al. 1997; Lu et al. 2010). The higher GVIA concentration in our study was used to ensure we could obtain data from multiple blockers applied to the same neuron. GVIA is a very high-affinity blocker, but the access to the blocking site is highly sensitive to divalent cation concentration (Boland et al. 1994; Liang and Elmslie 2002; Wagner et al. 1988). Thus the blocking rate is much lower in higher divalent cation concentrations (Boland et al. 1994; Liang and Elmslie 2002; Wagner et al. 1988) and also much slower in Ca2+ vs. Ba2+ (Liang and Elmslie 2001). Thus our data collection when using 10 mM Ca2+ was greatly enhanced by the fast block achieved using a higher GVIA concentration. Unlike GVIA, there is evidence that Nif and AgaIVa lose selectivity at higher concentrations. Nif has been shown to block non-L-type CaV currents at 10 μM (Jones and Jacobs 1990), which was one reason for our use of 3 μM. We were also able to achieve fast block of L-type channels using this Nif concentration. AgaIVa is highly specific for CaV2.1 channels at submicromolar concentrations, but CaV2.2 channels are blocked at concentrations ≥ 1 μM (Sidach and Mintz 2000). Thus, like other studies, we utilized 0.2 μM AgaIVa for most of our experiments. However, the Q-type variant of CaV2.1 is less sensitive to AgaIVa than the P-type variant (Bourinet et al. 1999; Randall and Tsien 1995). Thus, when determining if lower affinity CaV2.1 channel variants were expressed in muscle afferents, we preblocked CaV2.2 channels with GVIA, which allowed us to show that only 4% of the total CaV current could be attributed to Q-like CaV2.1 channels. Since resistant current comprises ∼25% of CaV current, our results suggest that Q-like CaV2.1 channels generate ∼16% (4%/25%) of resistant current.

Current that is resistant to the classic CaV channel blockers (e.g., GVIA, AgaIVa, and Nif) was originally termed R-current (Randall and Tsien 1995). The identification of CaV2.3 (α1E) fit the characteristics of R-current, and this channel type was called R-type (Zhang et al. 1993). SNX was identified as a blocker of CaV2.3 channels, but only a subpopulation of those channels was sensitive to this blocker (Tottene et al. 2000). We found that 22–27% of our CaV current was resistant to the classic CaV channel blockers, but that current was also insensitive to SNX. Two obvious possibilities were that CaV2.3 channels were not expressed in muscle afferent neurons, or SNX-insensitive variants were expressed in these neurons. We conclude that CaV2.3 channels are expressed in muscle afferent neurons, but these channels are insensitive to SNX, regardless of whether Ca2+ or Ba2+ was used to record current. This conclusion is based on three lines of evidence. First, muscle afferent neurons were labeled by a CaV2.3 antibody. Second, the deactivation of CaV current in the presence of GVIA and AgaIVa was slowed by roscovitine. GVIA and AgaIVa block CaV2.2 and 2.1, respectively, and roscovitine has been shown to specifically slow deactivation of CaV2 channels, including CaV2.3 channels (Buraei et al. 2007). A small component (∼16%) of this effect can be attributed to the Q-like current, but the robust roscovitine response supports expression of CaV2.3 in muscle afferent neurons. Finally, the potent Ni2+ block of the resistant current recorded in 10 mM Ca2+ (IC50 = 4.4 μM) is consistent with the majority (64%) of that current being generated by the activity of CaV2.3 channels (Won et al. 2006). The difference in Ni2+ blocking affinity in Ca2+ vs. Ba2+ external solutions is also consistent with the current being generated by CaV2.3 channels (Zamponi et al. 1996).

ATP modulation of CaV2.2 channels.

ATP is an important regulator of the EPR (Cui et al. 2011; Hanna and Kaufman 2003; Hayes et al. 2008) primarily via activation of ionotropic P2X receptors (Cui et al. 2011; Hanna and Kaufman 2004; Hayes et al. 2008). While it is clear that activation of G protein-coupled P2Y receptors cannot generate the EPR (Hayes et al. 2008), it is possible that activation of these receptors could modulate the reflex. One potential mechanism for that modulation is via CaV channels. ATP has been shown to inhibit CaV2.2 channels by activation of P2Y receptors (Filippov et al. 2003; Gerevich et al. 2004). Since the majority of neurons recorded for this study had small to medium diameters and all expressed NaV1.8, these neurons are likely group III and IV neurons that participate in the EPR (Kaufman and Hayes 2002). Thus we were interested in the effect of ATP on CaV current in our muscle afferent neurons. We found that ATP inhibited CaV current, and this inhibition primarily involved CaV2.2 channels. While we did not specifically test the involvement of P2Y receptors, there is no doubt that the inhibition is mediated via activation of G protein-coupled receptors. G protein-mediated inhibition of CaV2 channels is characterized by rapid reversal following strong depolarization (Elmslie 1992; Ikeda 1991; Meza and Adams 1998), which was exhibited by the ATP-induced inhibition of CaV current in our study. In addition, this type of inhibition is specifically mediated by the G protein βγ-subunit (Ikeda 1996). Thus ATP activation of G protein-coupled receptors (likely P2Y) inhibits CaV2.2 channels in muscle afferent neurons by G protein βγ-subunits binding directly to the channels (Elmslie and Jones 1994; Zamponi and Snutch 1998).

CaV2.2 channels are one of the primary CaV channel types that trigger excitatory neurotransmitter release from nociceptor synaptic terminals in the dorsal horn (Elmslie 2004; Vanegas and Schaible 2000; Zamponi et al. 2009), which is the reason for the clinical effectiveness of the CaV2.2 channel blocker ziconotide in controlling pain in chronic pain patients (Elmslie 2004; Snutch 2005; Zamponi et al. 2009). Activation of P2Y receptors in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord was shown to inhibit nociceptor synaptic transmission by inhibition of CaV2.2 (N-type channels), which was associated with reduced pain responses (Gerevich et al. 2004). Thus activation of P2Y receptors on group III and/or IV muscle afferent synaptic terminals could inhibit CaV2.2 channel activity to reduce cardiovascular effects of the EPR. These results also suggest that intrathecal application of ziconotide could be used to treat excessive EPR activity resulting from peripheral vascular disease or heart failure (Baccelli et al. 1999; Bakke et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2006).

CaV channel control of neuronal excitability.

CaV channel activity can produce either an increase or decrease in neuronal excitability, depending on the Ca2+-sensitive proteins activated by the Ca2+ influx. As discussed above, inhibition of CaV channels in excitatory presynaptic terminals (e.g., primary sensory neurons) inhibits excitability. On the other hand, inhibition of CaV channel activity can also lead to enhanced neuronal excitability through reduced activation of Ca2+-activated potassium channels (Marrion and Tavalin 1998; Yu et al. 2010). In a animal models of chronic pain, a reduction of CaV2.2 currents in small DRG neurons (Fuchs et al. 2007), and small to medium cutaneous afferent neurons (Lu et al. 2010) has been demonstrated. This reduction leads to enhanced excitability, which may help to produce chronic pain (Hogan et al. 2008; Lirk et al. 2008). The prominent expression of CaV2.2 channels by group III and IV neurons suggests that peripheral application of ziconotide or GVIA could enhance action potential activity in these neurons to increase EPR-induced effects on the cardiovascular system. However, natural activators could achieve the same effect. The ATP level in muscle has been demonstrated to depend on muscle contraction (Li et al. 2003; Mortensen et al. 2011), and the concentration (10 μM) is consistent with that used in this study (Li et al. 2003). If P2Y receptors and CaV2.2 channels are expressed on afferent endings in skeletal muscle, muscle released ATP could enhance the EPR via inhibition of CaV2.2 channels.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant AR-059397 (K. S. Elmslie and V. Ruiz-Velasco).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.R., S.G.M., V.R.-V., and K.S.E. conception and design of research; R.R., B.H., S.G.M., J.D., M.F., and V.R.-V. performed experiments; R.R., B.H., S.G.M., J.D., M.F., V.R.-V., and K.S.E. analyzed data; R.R., B.H., S.G.M., J.D., M.F., V.R.-V., and K.S.E. interpreted results of experiments; R.R., S.G.M., V.R.-V., and K.S.E. prepared figures; R.R., V.R.-V., and K.S.E. drafted manuscript; R.R., B.H., S.G.M., J.D., M.F., V.R.-V., and K.S.E. edited and revised manuscript; R.R., B.H., S.G.M., J.D., M.F., V.R.-V., and K.S.E. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Annette Dolphin for suggesting that we consider a non-SNX486 pharmacological test for functional CaV2.3 channels.

REFERENCES

- Baccelli G, Reggiani P, Mattioli A, Corbellini E, Garducci S, Catalano M. The exercise pressor reflex and changes in radial arterial pressure and heart rate during walking in patients with arteriosclerosis obliterans. Angiology 50: 361–374, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke EF, Hisdal J, Jorgensen JJ, Kroese A, Stranden E. Blood pressure in patients with intermittent claudication increases continuously during walking. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 33: 20–25, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland LM, Morrill JA, Bean BP. Omega-conotoxin block of N-type calcium channels in frog and rat sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci 14: 5011–5027, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Soong TW, Sutton K, Slaymaker S, Mathews E, Monteil A, Zamponi GW, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Splicing of alpha 1A subunit gene generates phenotypic variants of P- and Q-type calcium channels. Nat Neurosci 2: 407–415, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Anghelescu M, Elmslie KS. Slowed N-Type Calcium Channel (CaV2.2) deactivation by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor roscovitine. Biophys J 89: 1681–1691, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Schofield G, Elmslie KS. Roscovitine differentially affects CaV2 and Kv channels by binding to the open state. Neuropharmacology 52: 883–894, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Perez-Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 411–425, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colecraft HM, Patil PG, Yue DT. Differential occurrence of reluctant openings in G-protein-inhibited N- and P/Q-type calcium channels. J Gen Physiol 115: 175–192, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Leuenberger UA, Blaha C, King NC, Sinoway LI. Effect of P2 receptor blockade with pyridoxine on sympathetic response to exercise pressor reflex in humans. J Physiol 589: 685–695, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouhri L, Fang X, Okuse K, Wood JN, Berry CM, Lawson SN. The TTX-resistant sodium channel Nav1.8 (SNS/PN3): expression and correlation with membrane properties in rat nociceptive primary afferent neurons. J Physiol 550: 739–752, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS. Calcium channel blockers in the treatment of disease. J Neurosci Res 75: 733–741, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS. Calcium current modulation in frog sympathetic neurones: multiple neurotransmitters and G proteins. J Physiol 451: 229–246, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS. Identification of the single channels that underlie the N-type and L-type calcium currents in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci 17: 2658–2668, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS, Jones SW. Concentration dependence of neurotransmitter effects on calcium current kinetics in frog sympathetic neurones. J Physiol 481: 35–46, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS, Zhou W, Jones SW. LHRH and GTP-gamma-S modify calcium current activation in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. Neuron 5: 75–80, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z, Park CK, Li HY, Kim HY, Park SH, Jung SJ, Kim JS, Monteil A, Oh SB, Miller RJ. Molecular Basis of Cav2.3 calcium channels in rat nociceptive neurons. J Biol Chem 282: 4757–4764, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippov AK, Simon J, Barnard EA, Brown DA. Coupling of the nucleotide P2Y4 receptor to neuronal ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 138: 400–406, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A, Rigaud M, Sarantopoulos CD, Filip P, Hogan QH. Contribution of calcium channel subtypes to the intracellular calcium signal in sensory neurons: the effect of injury. Anesthesiology 107: 117–127, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathi SB, Kester M, Elmslie KS. State-dependent block of HERG potassium channels by R-roscovitine: implications for cancer therapy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C701–C710, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerevich Z, Borvendeg SJ, Schröder W, Franke H, Wirkner K, Nörenberg W, Fürst S, Gillen C, Illes P. Inhibition of N-type voltage-activated calcium channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons by P2Y receptors is a possible mechanism of ADP-induced analgesia. J Neurosci 24: 797–807, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna RL, Kaufman MP. Activation of thin-fiber muscle afferents by a P2X agonist in cats. J Appl Physiol 96: 1166–1169, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna RL, Kaufman MP. Role played by purinergic receptors on muscle afferents in evoking the exercise pressor reflex. J Appl Physiol 94: 1437–1445, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan B, Ruiz-Velasco V. The kappa-opioid receptor agonist U-50488 blocks Ca2+ channels in a voltage- and g protein-independent manner in sensory neurons. Reg Anesth Pain Med 38: 21–27, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SG, McCord JL, Kaufman MP. Role played by P2X and P2Y receptors in evoking the muscle chemoreflex. J Appl Physiol 104: 538–541, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Q, Lirk P, Poroli M, Rigaud M, Fuchs A, Fillip P, Ljubkovic M, Gemes G, Sapunar D. Restoration of calcium influx corrects membrane hyperexcitability in injured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Anesth Analg 107: 1045–1051, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houk J. Feedback control of muscle: a synthesis of the peripheral mechanisms. In: Medical Physiology, edited by Mountcastle VB. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1974, p. 668–677 [Google Scholar]

- Hu P, McLachlan EM. Selective reactions of cutaneous and muscle afferent neurons to peripheral nerve transection in rats. J Neurosci 23: 10559–10567, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CS, Song JH, Nagata K, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T. Effects of the neuroprotective agent riluzole on the high voltage-activated calcium channels of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282: 1280–1290, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Matsumoto S. Classification of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in trigeminal ganglion neurons from neonatal rats. Life Sci 73: 1175–1187, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR. Double-pulse calcium channel current facilitation in adult rat sympathetic neurones. J Physiol 439: 181–214, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature 380: 255–258, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Joksovic PM, Lee W, Nelson MT, Naik AK, Su P, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. Upregulation of the T-type calcium current in small rat sensory neurons after chronic constrictive injury of the sciatic nerve. J Neurophysiol 99: 3151–3156, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SW, Jacobs LS. Dihydropyridine actions on calcium currents of frog sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci 10: 2261–2267, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MP, Hayes SG. The exercise pressor reflex. Clin Auton Res 12: 429–439, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravani H, Zamponi GW. Voltage-gated calcium channels and idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Physiol Rev 86: 941–966, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, King NC, Sinoway LI. ATP concentrations and muscle tension increase linearly with muscle contraction. J Appl Physiol 95: 577–583, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Elmslie KS. E(f)-current contributes to whole-cell calcium current in low calcium in frog sympathetic neurons. J Neurophysiol 86: 1156–1163, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Elmslie KS. Rapid and reversible block of N-type calcium channels (CaV 2.2) by omega-conotoxin GVIA in the absence of divalent cations. J Neuroscience 22: 8884–8890, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lirk P, Poroli M, Rigaud M, Fuchs A, Fillip P, Huang CY, Ljubkovic M, Sapunar D, Hogan Q. Modulators of calcium influx regulate membrane excitability in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Anesth Analg 107: 673–685, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Raghavachari S, Tsien RW. The sequence of events that underlie quantal transmission at central glutamatergic synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 597–609, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SG, Zhang XL, Luo ZD, Gold MS. Persistent inflammation alters the density and distribution of voltage-activated calcium channels in subpopulations of rat cutaneous DRG neurons. Pain 151: 633–643, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrion NV, Tavalin SJ. Selective activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by co-localized Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurons. Nature 395: 900–905, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meza U, Adams B. G-protein-dependent facilitation of neuronal alpha1A, alpha1B, and alpha1E Ca channels. J Neurosci 18: 5240–5252, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinski TF, Dalisay DS, Lievens SL, Saludes JP. Drug development from marine natural products. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8: 69–85, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen SP, Thaning P, Nyberg M, Saltin B, Hellsten Y. Local release of ATP into the arterial inflow and venous drainage of human skeletal muscle: insight from ATP determination with the intravascular microdialysis technique. J Physiol 589: 1847–1857, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motin L, Adams DJ. Omega-conotoxin inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission evoked by dorsal root stimulation in rat superficial dorsal horn. Neuropharmacology 55: 860–864, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnami S, Tanabe M, Shinohara S, Takasu K, Kato A, Ono H. Role of voltage-dependent calcium channel subtypes in spinal long-term potentiation of C-fiber-evoked field potentials. Pain 152: 623–631, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl HL, Ikeda SR. Identification of the sensory neuron specific regulatory region for the mouse gene encoding the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.8. J Neurochem 106: 1209–1224, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra R, McGrew SY, Baxter JC, Howard JR, Elmslie KS. NaV1.8 channels are expressed in large, as well as small, diameter sensory afferent neurons. Channels (Austin) 7: 34–37, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra R, McGrew SY, Baxter JC, Kiveric E, Elmslie KS. Tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-dependent sodium (NaV) channels in identified muscle afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol 108: 2230–2241, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall A, Tsien RW. Pharmacological dissection of multiple types of Ca2+ channel currents in rat cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci 15: 2995–3012, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Calcium current variation between acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons of different size. J Physiol 445: 639–658, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidach SS, Mintz IM. Low-affinity blockade of neuronal N-type Ca channels by the spider toxin omega-agatoxin-IVA. J Neurosci 20: 7174–7182, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SA, Mitchell JH, Garry MG. The mammalian exercise pressor reflex in health and disease. Exp Physiol 91: 89–102, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snutch TP. Targeting chronic and neuropathic pain: the N-type calcium channel comes of age. NeuroRx 2: 662–670, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottene A, Volsen S, Pietrobon D. Alpha(1E) subunits form the pore of three cerebellar R-type calcium channels with different pharmacological and permeation properties. J Neurosci 20: 171–178, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas H, Schaible HG. Effects of antagonists to high-threshold calcium channels upon spinal mechanisms of pain, hyperalgesia and allodynia. Pain 85: 9–18, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Snowman A, Biswas A, Olivera B, Snyder S. Omega-conotoxin GVIA binding to a high-affinity receptor in brain: characterization, calcium sensitivity, and solubilization. J Neurosci 8: 3354–3359, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won YJ, Whang K, Kong ID, Park KS, Lee JW, Jeong SW. Expression profiles of high voltage-activated calcium channels in sympathetic and parasympathetic pelvic ganglion neurons innervating the urogenital system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 317: 1064–1071, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarotskyy V, Elmslie KS. Roscovitine inhibits CaV3.1 (T-type) channels by preferentially affecting closed-state inactivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340: 463–472, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarotskyy V, Elmslie KS. Roscovitine, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, affects several gating mechanisms to inhibit cardiac L-type (CaV1.2) calcium channels. Br J Pharmacol 152: 386–395, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Maureira C, Liu X, McCormick D. P/Q and N channels control baseline and spike-triggered calcium levels in neocortical axons and synaptic boutons. J Neurosci 30: 11858–11869, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, Bourinet E, Snutch TP. Nickel block of a family of neuronal calcium channels: subtype- and subunit-dependent action at multiple sites. J Membr Biol 151: 77–90, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, Lewis RJ, Todorovic SM, Arneric SP, Snutch TP. Role of voltage-gated calcium channels in ascending pain pathways. Brain Res Rev 60: 84–89, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, Snutch TP. Decay of prepulse facilitation of N type calcium channels during G protein inhibition is consistent with binding of a single Gbeta subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 4035–4039, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JF, Randall AD, Ellinor PT, Horne WA, Sather WA, Tanabe T, Schwarz TL, Tsien RW. Distinctive pharmacology and kinetics of cloned neuronal Ca2+ channels and their possible counterparts in mammalian CNS neurons. Neuropharmacology 32: 1075–1088, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]