Abstract

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis represents approximately 0.5% of all cancers among men in the United States and other developed countries. Although rare, it is associated with significant disfigurement, and only half of the patients survive beyond 5 years. Proper evaluation of both the primary lesion and lymph nodes is critical, because nodal involvement is the most important factor of survival. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Penile Cancer provide recommendations on the diagnosis and management of this devastating disease based on evidence and expert consensus.

Overview

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the penis is a rare disease, representing 0.4% to 0.6% of all malignant neoplasms among men in the United States and Europe.1 In 2012, the estimated number of new penile cancer cases in the United States was 1570, with 310 cancer-specific deaths predicted.2 The incidence is higher (up to 10%) among men in the developing countries of Asia, Africa, and South America. The most common age of presentation is between 50 and 70 years.3 Early diagnosis is of utmost importance, because this disease can result in devastating disfigurement and has a 5-year survival rate of approximately 50% (>85% for patients with negative lymph nodes and 29%–40% for patients with positive nodes, with the lowest survival rates at 0% for patients with pelvic lymph node (PLN) involvement).4 As the rarity of this disease makes it difficult to perform prospective, randomized trials, the NCCN Penile Cancer Panel relied on the experience of penile cancer experts to minimize the controversies associated with treating penile SCC and collectively lay a foundation to help standardize the management of the malignancy.

Risk Factors

In the United States, the median age of penile cancer diagnosis is 68 years, with an increased risk in men older than 50 years.5 Early detection is assisted by the ability to perform a good physical examination. Phimosis may hinder the ability to properly inspect the areas of highest incidence: the glans, inner preputial layer, coronal sulcus, and shaft. Men with phimosis carry an increased risk of 25% to 60%.3,6,7 A more recent review of penile SCC in the United States showed that 34.5% of patients had the primary lesion on the glans, 13.2% on the prepuce, and 5.3% in the shaft, with 4.5% overlapping and 42.5% unspecified.5 Other risk factors include balanitis, chronic inflammation, penile trauma, tobacco use, lichen sclerosus, poor hygiene, and a history of sexually transmitted diseases, especially HIV and human papillomavirus (HPV).3 Overall, 45% to 80% of penile cancers are related to HPV, with a strong correlation with types 16 and 18.3,6,8,9 Patients with HIV have an 8-fold increased risk, which may correspond to a higher incidence of HPV among men with HIV.10 Cigarette smokers are noted to be 3.0 to 4.5 times more likely to develop penile cancer.8,11 Patients with lichen sclerosus are noted to have a 2% to 9% risk of developing penile carcinoma.12–14 The incidence among patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus ultraviolet A is 286 times that of the general population. Therefore, these patients should be shielded during treatment, and any penile lesion should be closely monitored.15

Clinical Presentation

Most often penile SCC presents as a palpable, visible lesion on the penis, which may be associated with penile pain, discharge, bleeding, or a foul odor if the patient delays seeking medical treatment. The lesion may be characterized as nodular, ulcerative, or fungating, and may be obscured by phimosis. The patient may exhibit signs of more advanced disease, including palpable nodes and/or constitutional symptoms (eg, fatigue, weight loss).

Characterization and Clinical Staging

SCC is the most common variant of penile cancer. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia is a premalignant condition at high risk of developing into penile SCC.16 The AJCC recognizes 4 subtypes of SCC: verrucous, papillary squamous, warty, and basaloid.17 The verrucous subtype is believed to be of low malignant potential, whereas other variants reported, such as adenosquamous and sarcomatoid, have a worse prognosis.18,19 The primary lesion is further characterized by its growth pattern with superficial spread, nodular or vertical-phase growth, and a verrucous pattern. In addition to the penile lesion, evaluation of lymph nodes is also critical, because involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes (ILNs), the number and site of positive nodes, and extracapsular nodal involvement provide the strongest prognostic factors of survival.4,20

The AJCC TNM system for penile carcinoma has been used for staging, with the most recent update published in 2010. It was initially introduced in 1968 and was subsequently revised in 1978, 1987, and 2002.17,21–24 In the 2010 update, the AJCC has made the distinction between clinical and pathologic staging while eliminating the difference between superficial and deep inguinal metastatic nodes.17 Other changes to the 2010 TNM system include T1 subdivided into T1a and T1b determined by the presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion or poorly differentiated cancers; the T3 category is now limited to urethral invasion and T4 is limited to prostatic invasion; and stage II grouping includes T1b,N0,M0 and T2–3,N0,M0 (see Staging Table in these guidelines, available online, at NCCN.org [ST-1]). A grading system for SCC of the penis based on degree of cell anaplasia is defined as grade 1, well-differentiated (no evidence of anaplasia); grade 2, moderately differentiated (<50% anaplasia); and grade 3, poorly differentiated (>50% anaplastic cells).25 According to the AJCC, if no grading system is specified, a general system should be followed: GX, grade cannot be assessed; G1–3 as mentioned previously; and G4, undifferentiated.17 The overall degree of cellular differentiation with high-risk, poorly differentiated tumors is an important predictor factor for metastatic nodal involvement.26 The AJCC also recommends collection of site-specific factors, including the distinction between corpus spongiosum and corpus cavernosum involvement, the percentage of tumor that is poorly differentiated, the depth of invasion in verrucous carcinoma, the size of the largest lymph node metastasis, and HPV status.17

Table 1.

Individual Disclosures for the NCCN Penile Cancer Panel

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support | Advisory Boards, Speakers Bureau, Expert Witness, or Consultant | Patent, Equity, or Royalty | Other | Date Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neeraj Agarwal, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/3/12 |

| Matthew C. Biagioli, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 10/16/12 |

| Peter E. Clark, MD | None | Archimedes Pharma Ltd. | None | None | 8/28/12 |

| Mario A. Eisenberger, MD | Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Genentech, Inc.; Agensys, Inc.; and sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC | Ipsen | None | None | 8/31/12 |

| Richard E. Greenberg, MD | None | Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. | None | None | 3/26/13 |

| Harry W. Herr, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/28/12 |

| Brant A. Inman, MD, MSc | GlaxoSmithKline plc | None | None | None | 8/28/12 |

| Deborah A. Kuban, MD | None | None | Immtech International, Inc. | None | 8/28/12 |

| Timothy M. Kuzel, MD | Bayer AG; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CureTech; Eli Lilly and Company; GlaxoSmithKline; Merck & Co., Inc.; Novartis AG; Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Alton Pharma, Inc.; Argos Therapeutics, Inc.; and Biovex Group, Inc. | Celgene Corporation; Exelixis Inc.; Genentech, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline plc; Jannsen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Novartis AG; Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Affymax, Inc.; AVEO Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Prometheus Laboratories Inc. | None | None | 8/28/12 |

| Subodh M. Lele, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/28/12 |

| Jeff Michalski, MD, MBA | None | None | None | None | 8/13/12 |

| Lance C. Pagliaro, MD | None | None | None | None | 1/4/13 |

| Sumanta K. Pal, MD | None | Genentech, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline plc; Novartis AG; Pfizer Inc.; and sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC | None | None | 3/27/12 |

| Anthony Patterson, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/15/12 |

| Elizabeth R. Plimack, MD, MS | None | Amgen Inc. | None | None | 10/17/12 |

| Kamal S. Pohar, MD | None | None | None | None | 9/27/12 |

| Michael P. Porter, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 4/25/12 |

| Jerome P. Richie, MD | None | None | None | None | 5/2/12 |

| Wade J. Sexton, MD | Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. | Endo Pharmaceuticals | None | None | 8/3/12 |

| William U. Shipley, MD | None | None | Pfizer Inc. | None | 8/28/12 |

| Eric J. Small, MD | None | Dendreon Corporation | None | None | 9/24/12 |

| Philippe E. Spiess, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 5/4/12 |

| Donald L. Trump, MD | None | None | None | None | 5/17/12 |

| Geoffrey Wile, MD | None | None | None | None | 6/13/12 |

| Timothy G. Wilson, MD | None | Covidien | None | None | 1/6/12 |

The NCCN guidelines staff have no conflicts to disclose.

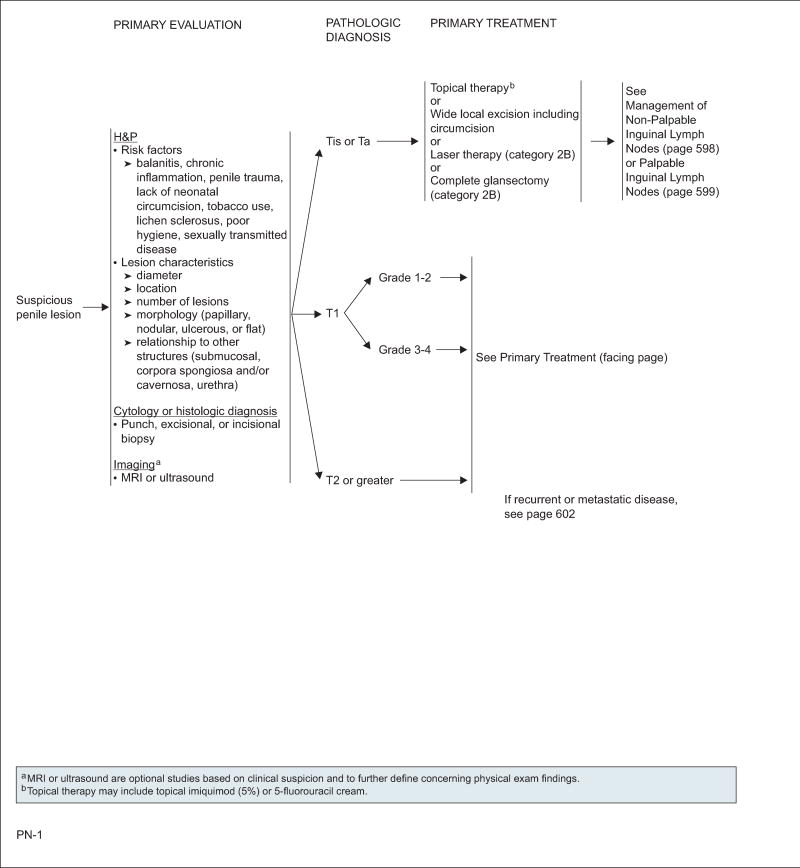

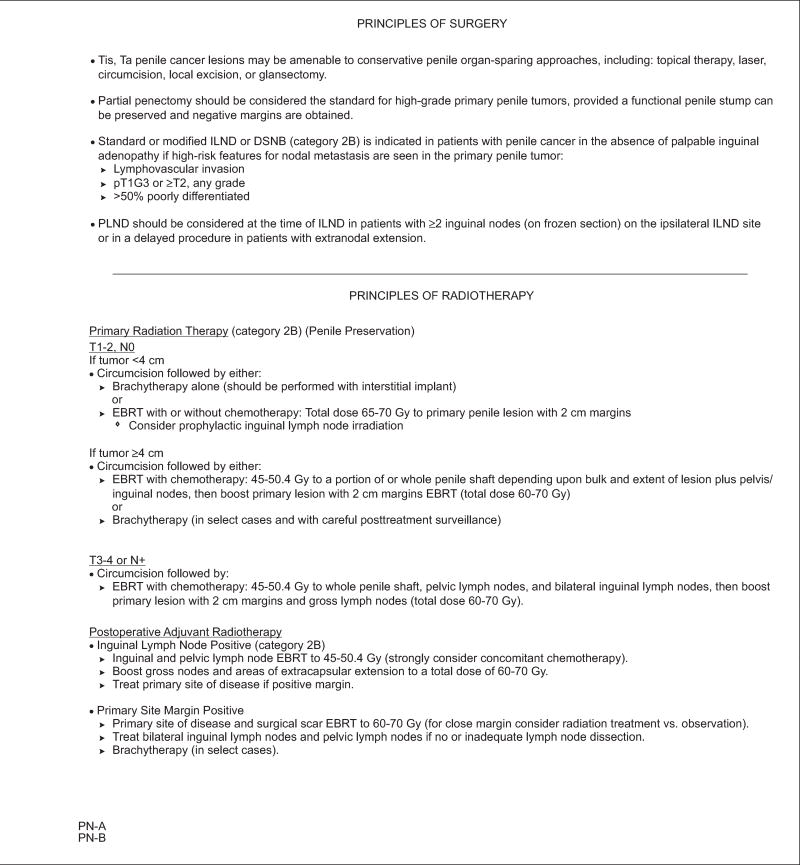

Management of Primary Lesions

Diagnosis

Evaluation of the primary lesion, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis will dictate the appropriate and adequate management of penile SCC, beginning with the first evaluation at presentation and then throughout follow-up. Vital to the initial management is a good physical examination of the penile lesions that remarks on the diameter of the lesions or suspicious areas; locations on the penis; number of lesions; morphology of the lesions; whether the lesions are papillary, nodular, ulcerous or flat; and relationship with other structures, including sub-mucosal, urethra, corpora spongiosa, and/or corpora cavernosa. To complete the initial evaluation, histologic diagnosis with a punch, excisional, or incisional biopsy is paramount in determining the treatment algorithm based on a pathologic diagnosis.17,27 This will provide information on the grade of the tumor and will assist in the risk stratification of the patient for regional lymph node involvement.27 MRI or ultrasound can be used to evaluate the depth of tumor invasion.28 For the evaluation of lymph nodes, see “Management of Regional Lymph Nodes,” this page.

NCCN Recommendations

Tis or Ta

For patients with penile carcinoma in situ or noninvasive verrucous carcinoma, penile-preserving techniques may be used, including topical imiquimod (5%) or 5-FU cream; circumcision and wide local excision such as Mohs surgery; laser therapy (category 2B) using carbon dioxide or neodynium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet; and complete glansectomy (category 2B). Among these, topical therapy29–31 and excisional organ-sparing surgery32 are the most widely used. Retrospective studies of laser therapy reported local recurrence rates of around 18% comparable to that of surgery, with good cosmetic and functional results.33,34 Glansectomy, removal of the glans penis, has also been studied, with no recurrence observed in some cases.35–38

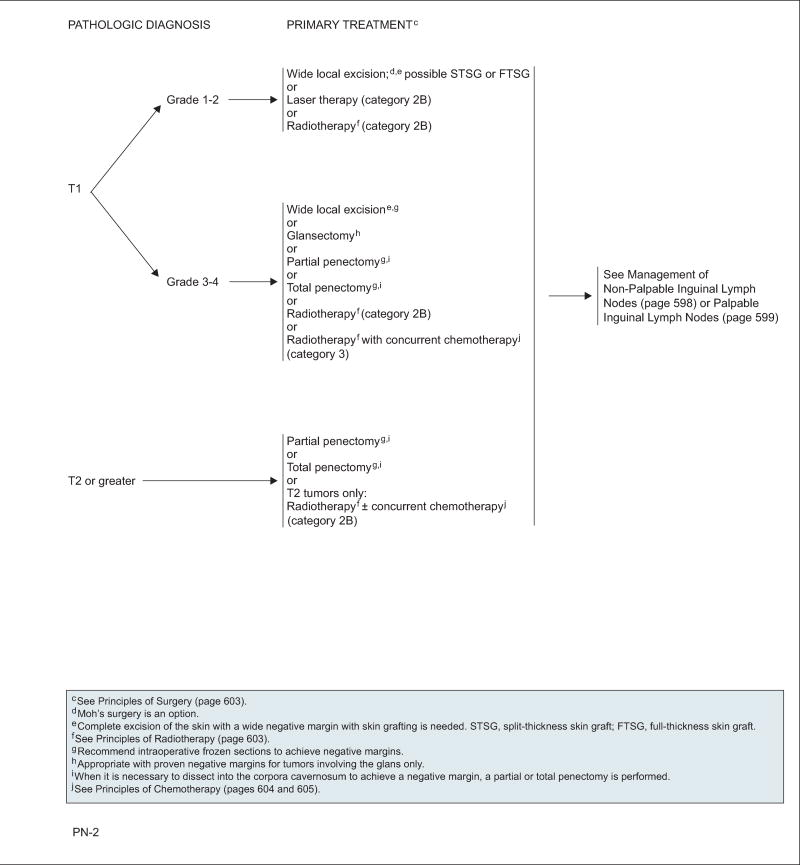

T1,G1–2

Careful consideration should be given to penile-preserving techniques if the patient is reliable regarding compliance with close follow-up. These techniques include wide local excision and Mohs surgery as an option plus reconstructive surgery39; laser therapy (category 2B)40; or radiotherapy (RT) delivered as external-beam RT (EBRT) or brachytherapy with interstitial implant (category 2B).41–45 Emphasis is placed again on patient selection and close follow-up, because the 2-year recurrence rate may reach up to 50%.46 Recent studies have shown that surgical margins of 5 to 10 mm are as safe as 2-cm surgical margins, and 10- to 20-mm margins provide adequate tumor control.47 Circumcision should always precede RT to prevent radiation-related complications.

T1,G3–4, T≥2

These lesions typically require more extensive surgical intervention with partial or total penectomy depending on the characteristics of the tumor and depth of invasion.27 Intraoperative frozen sectioning is recommended to achieve negative surgical margins. If the tumor encompasses less than half the glans and the patient agrees to very close observation, then a more conservative approach, such as wide local excision or glansectomy, may be considered. The patient should understand that they have an increased risk for recurrence and that the potential exists that a repeat wide local excision may be needed should a local recurrence be noted, provided there is no invasion of the corpora cavernosa.34,38 A clear and frank discussion should be conducted with the patient regarding the likelihood that a partial or total penectomy will be required should a larger or more invasive lesion be present.

Tumor size is an important factor when choosing RT as treatment. Because the average length of the glans is approximately 4 cm, this serves as a cutpoint to reduce the risk of undertreating cavernosal lesions. In a study of 144 patients with penile cancer restricted to the glans treated with brachytherapy, larger tumors, especially those greater than 4 cm, are associated with higher risk of recurrence.48 A high 10-year cancer-specific survival rate of 92% was achieved in this series.

The NCCN panel reached nonuniform consensus on the use of RT as primary therapy. For T1,G3–4 tumors, RT is a category 2B recommendation, whereas RT with concurrent chemotherapy is a category 3 recommendation. For T2 tumors, RT with or without chemotherapy is a category 2B option. RT should be given after circumcision has been performed.

For tumors smaller than 4 cm, brachytherapy with interstitial implant or EBRT with or without chemotherapy are viable options. Prophylactic ILN irradiation should be considered if selecting EBRT. For tumors 4 cm or larger, EBRT combined with chemotherapy may be used. Brachytherapy may still be appropriate in select cases, but careful monitoring is necessary as the risks of complications and failures increase.49 Crook et al45 reported a 10-year cause-specific survival of 84% in 67 patients with T1–2 (select cases of T3) penile lesions treated with primary brachytherapy.

Postsurgical RT to the primary tumor site may be considered for positive margins.

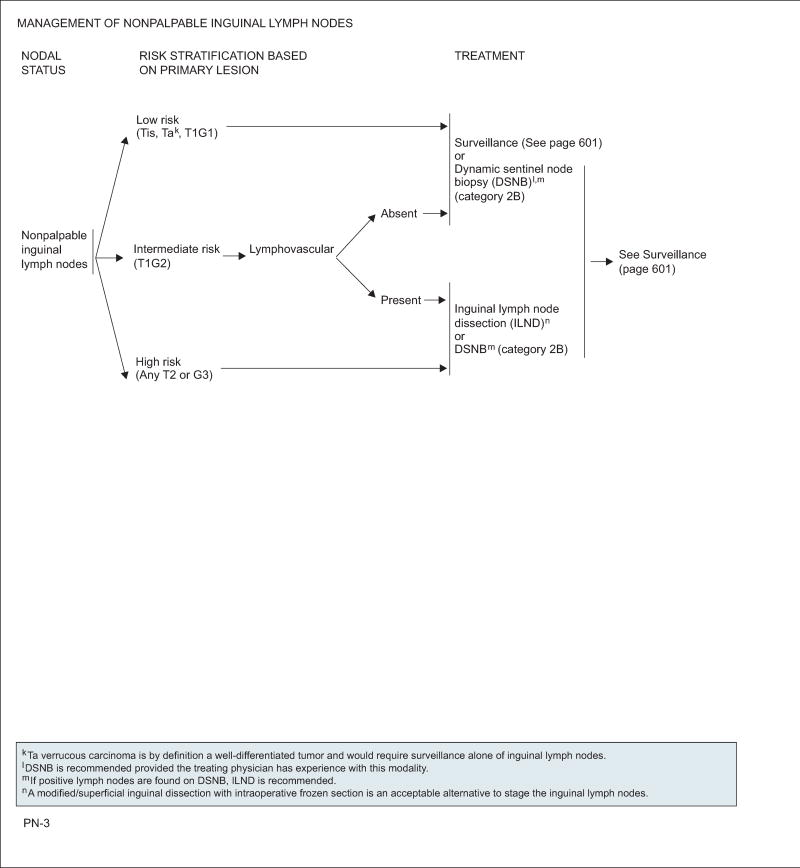

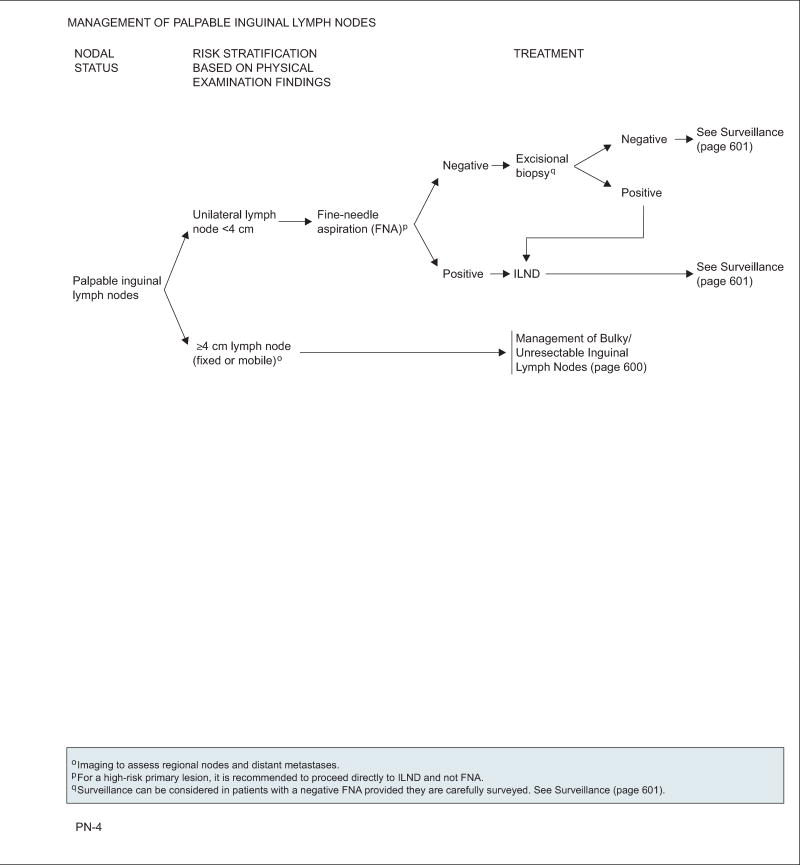

Management of Regional Lymph Nodes

Evaluation and Risk Stratification

The presence and extent of regional ILN metastases has been determined to be the single most important prognostic indicator in determining long-term survival in men with invasive penile SCC.20 Evaluation of the groin and pelvis is an essential component of the metastatic workup of a patient. The involvement of the ILN can be clinically evident (ie, palpable vs nonpalpable), adding to the difficulty in management. Clinical examination for ILN involvement should attempt to evaluate and assess for palpability, number of inguinal masses, unilateral or bilateral, dimensions, mobility or fixation of nodes or masses, relationship to other structures (eg, skin, Cooper ligaments), and edema of the penis, scrotum, and/or legs.50,51 Crossover drainage from left to right and vice versa does occur and is reproducible with lymphoscintigraphy.4,52 The physical examination should describe the diameter of nodes or masses, unilateral or bilateral localization, number of nodes identified in each inguinal, and the relationship to other structures (eg, skin, Cooper ligament), with respect to infiltration and perforation. CT or MRI for palpable disease may be used to assess the size, extent, location, and structures that are in proximity to the ILN, and the presence of pelvic and retro-peritoneal lymph nodes and distant metastasis. CT and MRI are limited in patients with nonpalpable disease.50,53 Although studies have examined the use of nanoparticle-enhanced MRI, PET/CT, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT, their small sample size requires validation in larger prospective studies.54–57 When considering one imaging modality to evaluate the stage of the primary lesion and lymph node status, MRI seems to be the best choice to not only enhance but also potentially replace the physical examination in patients in whom the inguinal region is difficult to assess (eg, morbidity, previous chemo/RT).54,58

Consideration must be given to whether the primary lesion showed any adverse prognostic factors. If one or more of these high-risk features is present, then pathologic ILN staging must be performed. Up to 25% of patients with nonpalpable lymph nodes harbor micrometastases.25 Therefore, several predictive factors have been evaluated to help predict the presence of occult lymph node metastasis.46,59 Slaton et al25 concluded that patients with pathologic stage T2 or greater were at significant risk (42%–80%) of nodal metastases if they exhibited greater than 50% poorly differentiated cancer and/or vascular invasion, and therefore an inguinal lymph node dissection (ILND) should be recommended.4,25 These factors can then further define patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups for lymph node metastasis.18,60,61 The European Association of Urology determined risk stratification groups for patients with nonpalpable ILNs, and validated this in both univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors. Patients can be stratified according to stage and/or grade into risk groups based on the likelihood of harboring occult node-positive disease, with the low-risk group defined as patients with Tis, Ta,G1–2 or T1,G1; the intermediate-risk group as those with T1,G2; and the high-risk group as those with T2 or G3.51,60

Dynamic Sentinel Node Biopsy

The work by Cabanas62 used lymphangiograms and anatomic dissections to evaluate the sentinel lymph node drainage for penile cancer with nonpalpable ILNs. This technique has been shown to have false-negative rates as high as 25%; therefore, it is no longer recommended.51,63 Advancements have been made with the dynamic sentinel node biopsy (DSNB) technique developed for penile cancer by the Netherlands Cancer Institute using lymphoscintigraphy and performed with tech-netium99m-labeled nanocolloid and patent blue dye isosulfan blue.64,65 Initially, this technique was associated with a low sensitivity and high false-negative rate (16%–43%).66–69 Refinement of the technique to improve the false-negative rate includes serial sectioning and immunohistochemical staining of pathologic specimens, preoperative ultrasonography with and without fine-needle aspiration cytology, and exploration of groins in which no sentinel node is visualized on intraoperative assessment, achieving a decrease in false-negative rate from 19% to only 5%.64,70 Using fine-needle aspiration with ultrasound can increase the diagnostic yield in metastasis greater than 2 mm in diameter.53,71 Crawshaw et al72 used ultrasound with DSNB and noted improved accuracy in identifying patients with occult lymph node metastases. With modification of the NCI protocol, Hadway et al73 were able to achieve a similar false-negative rate (5%) with an 11-month follow-up. Secondary to the technical challenges associated with DSNB, to be accurately and reliably performed, it is recommended that DSNB be performed at tertiary care referral centers where at least 20 procedures are performed per year.64,74 It should be noted that DSNB is not recommended in patients with palpable ILNs.50

Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection

The most frequent site of metastasis is the ILN, typically presenting as palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy. Management of the ILN with ILND has been fraught with great fears of surgical morbidity.51,75 Early treatment of lymph node involvement has been shown to have a positive impact on survival, except if the patient has bulky nodal spread or other sites of metastases.76,77 Palpable lymphadenopathy at diagnosis does not warrant an immediate ILND. Of the patients with palpable disease, 30% to 50% of these cases will be secondary to inflammatory lymph node swelling instead of metastatic disease.59 Although the distinction between reactive lymph nodes and metastatic disease may be made after a 6-week course of antibiotics, fine-needle aspiration is becoming the most favored approach among many penile cancer experts.4,50 In this setting, antibiotics are useful if the patient has a suspected underlying cellulitis at the site of palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy and future site of ILND.4,50,78

In attempts to decrease the morbidity associated with standard ILND, Catalona79 pioneered a modified lymphadenectomy surgical approach in 1988. This technique uses a shorter skin incision, limiting the field of inguinal dissection through excluding the area lateral to the femoral artery and caudal to the fossa ovalis, with preservation of the saphenous vein and elimination of the need to transpose the sartorius muscle while providing an adequate therapeutic effect. This technique is commonly reserved for patients with a primary tumor that places them at increased risk for inguinal metastasis and clinically negative groins on examination.78 The modified technique has shown a decrease in complications by preserving the saphenous vein and leaving the sartorius muscle in place. Contemporary modified ILND should include the central and superior zones of the inguinal region because these sections were not included in the dissection, leading to a false-positive rate of 15%.80,81 If nodal involvement is detected on frozen section, the surgical procedure should be converted to a standard extended lymphadenectomy.

A standard extended lymphadenectomy may be considered if the patient has resectable metastatic adenopathy, although recent studies would favor a neoadjuvant chemotherapy approach followed by surgical consolidation.82,83 Generally, the procedure follows the primary tumor treatment by 4 to 6 weeks. Again during this time, antibiotics may be administered if an overlying cellulitis is suspected at the future surgical site. The extent of the standard ILND includes the superficial and deep ILNs. The boundaries of the dissection are defined by the superior margin of the external ring to the anterior superior iliac spine, laterally from the anterior superior iliac spine extending 20 cm inferiorly and medially to a line drawn from the pubic tubercle 15 cm downward.78 Typically it is recommended to keep the patient on bed rest for 48 to 72 hours, especially after myocutaneous flaps or the repair of large skin defects. The drains are removed when drainage is less than 30 to 50 mL/d, usually 3 to 17 days postoperatively.78,84 Consideration should be given to keeping the patient on a suppressive dose of an oral cephalosporin (or other gram-positive–covering broad-spectrum antibiotic) for several weeks postoperatively in an attempt to decrease the risk of wound-related issues and minimize the risk for overall complications.78

Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) includes the lymph nodes along the external iliac vessels and in the obturator fossa (up to 12–20 nodes). Crossover from one pelvic side to the other has not been observed, unlike crossover at the inguinal level.4 The limits of the PLND include the iliac bifurcation for proximal, ilioinguinal nerve for lateral, and obturator nerve for medial boundary.51,78 Consideration should be given to performing a PLND only among patients with 2 or more positive ILNs, extracapsular nodal extension, or poorly differentiated metastases, as highlighted in a retrospective study by Lont et al.85

Advances in Surgical Approach: Video/Endoscopy

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, including video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy (VEIL) or robotic-assisted laparoscopy, offer the potential for fewer cutaneous complications while attempting to maintain comparable oncologic outcomes.86–88 The endoscopic approach was initially described by Bishoff et al89 in 2003, with a subcutaneous modified inguinal lymphadenectomy in 2 cadaveric models. The patient selection for VEIL includes those who warrant an open procedure, such as those 1) with palpable lymphadenopathy and 2) with nonpalpable nodes and a T2 or greater primary tumor in the presence of high-grade features and/ or vascular invasion. The lymph node template is as described by Catalona79 for the modified inguinal lymphadenectomy; a difference is that this technique does not always preserve the saphenous vein. The boundaries of the dissection include the sartorius muscle laterally, the adductor longus muscle medially, and the inguinal ligament and spermatic cord superiorly. Tobias-Machado et al86 modified the technique from Bishoff’s series and selected patients with nonpalpable ILNs for their first successful report. In another series,87 they reported that they obtained good results with VEIL, meaning that they were able to dissect and excise the same number of nodes in patients who had an open procedure on one groin and a VEIL procedure on the other groin. The patients reported increased pain with the open procedure compared with the laparoscopic approach. This series of 10 patients recorded no recurrences or cases of disease progression with a mean follow-up of 18.7 months. Subsequently, these investigators88 presented a comparative study of 20 groins that underwent VEIL and 10 that underwent an open procedure. This series had complication rates of 70% for the open procedure and 20% for the VEIL procedure, with no recurrences at median follow-up of 33 months. Sotelo et al90 also used the endoscopic approach in 8 patients (14 lymphadenectomies) and noted no perioperative or wound-related complications, with 3 groins (23%) developing a lymphocele. Minimally invasive techniques show promise, with reduced complication rates while preserving the principles of oncologic surgery. Nevertheless, the open surgical approach currently should be considered the standard, and laparoscopic approaches will require validation in larger surgical series and longer follow-up before they can be recommended.

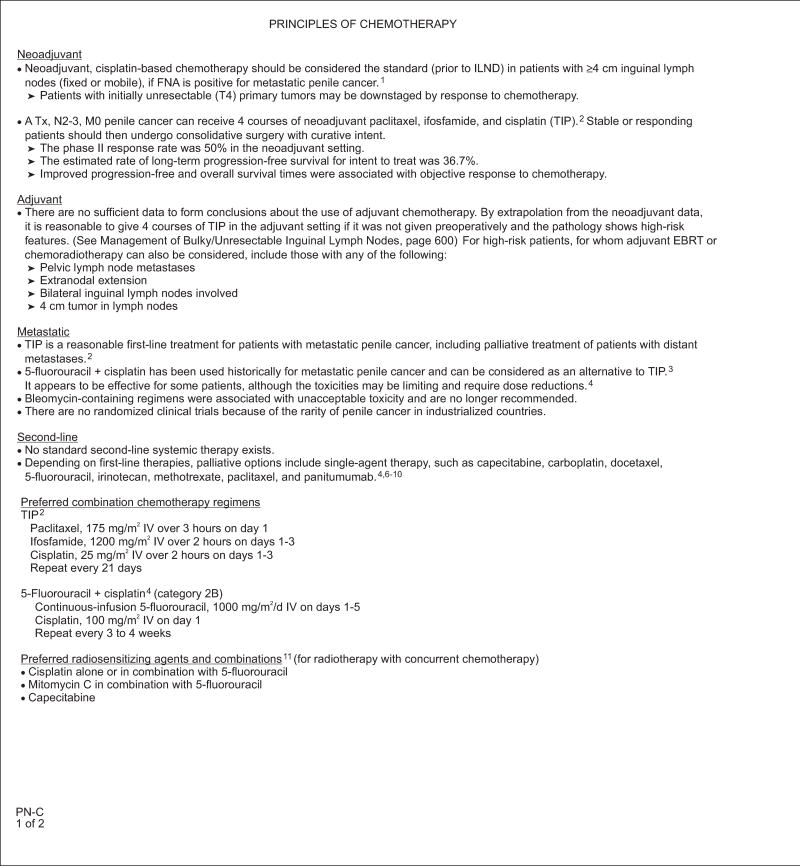

Chemotherapy

A patient who presents with resectable bulky disease will rarely be cured with a single treatment modality. Consideration should be given to neoadjuvant chemotherapy if ILNs are 4 cm or greater. One of the most commonly used neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy regimens is a combination of bleomycin, methotrexate, and cisplatin (BMP).91 Patients who may benefit from surgical consolidation would be those who had a stable, partial, or complete response after systemic chemotherapy, thus increasing their potential for disease-free survival.82,83 Recently, Pagliaro et al92 performed a phase II clinical trial in 30 patients with stage N2 or N3 (stage III or IV) penile cancer without distant metastases receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin. In their series, 50% of patients were noted to have a clinically meaningful response, and 22 (73.3%) subsequently underwent surgery. An improved time to progression and overall survival were associated with chemotherapy responsiveness (P<.001 and P=.001, respectively), absence of bilateral residual tumor (P=.002 and P=.017, respectively), and absence of extranodal extension (P=.001 and P=.004, respectively) or skin involvement (P=.009 and P=.012, respectively).

NCCN Recommendations

Nonpalpable Nodes

Most low-risk patients and intermediate-risk patients without lymphovascular invasion are followed with a surveillance protocol, because the probability of occult micrometastases in ILNs is less than 17%.60,93 For patients in the high-risk group (T2 or G3) and intermediate-risk patients with lymphovascular invasion, a modified or radical inguinal lymphadenectomy is strongly recommended, because occult metastatic disease ranges between 68% and 73%.46,60,93 If positive nodes are present on the frozen section, then a superficial and deep inguinal lymphadenectomy should be performed (with consideration of a PLND).

Because DSNB is currently not widely practiced in the United States, it is a category 2B option for examining nonpalpable nodes to determine the need for a modified lymphadenectomy in place of predictive factors.94,95 This technique should be performed in tertiary care referral centers with substantial experience. DSNB is not recommended for Ta tumors, because observation alone of the inguinal lymph nodes is sufficient for these well-differentiated lesions in the absence of palpable adenopathy.

Unilateral Palpable Nodes <4 cm

Fine-needle aspiration of the lymph nodes is considered standard for these patients. However, the panel recommends omitting the procedure for patients with high-risk primary lesions to avoid delay of lymphadenectomy. A negative fine-needle aspiration biopsy should be confirmed with an excisional biopsy. Alternatively, careful surveillance may be considered following a negative fine-needle aspiration. Positive findings from either procedure warrant an immediate ILND.

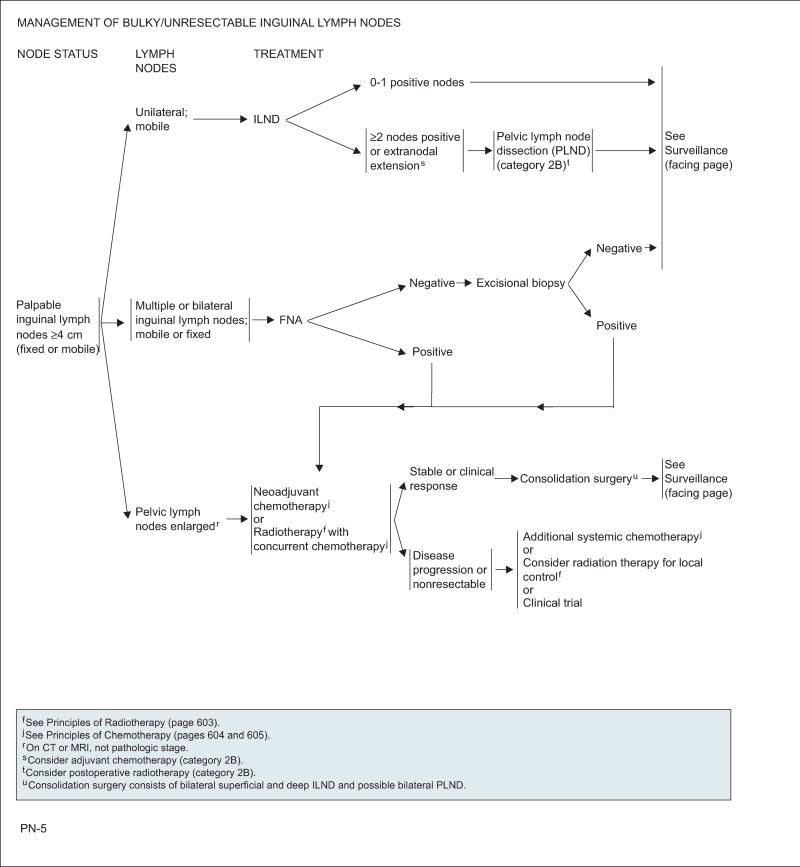

Palpable Nodes ≥4 cm (Fixed or Mobile)

Large, unilateral, mobile nodes are amenable to standard or modified ILND. No further treatment is necessary when only a single node or none is confirmed. Management is controversial otherwise. Category 2B is assigned to adjuvant chemotherapy when extranodal extension is found. PLND with or without postoperative radiation is also a category 2B recommendation in the presence of 2 or more positive inguinal nodes on the ipsilateral ILND site or extranodal involvement.

Patients with abnormal PLNs on imaging (CT or MRI) should receive either systemic chemotherapy or concurrent chemoradiation with consideration of a confirmatory percutaneous biopsy or PET/CT. Those whose disease responds to therapy or who become stable should undergo bilateral superficial and deep ILND and bilateral PLND if possible. For unresectable cases or on disease progression, patients may consider the following options: additional systemic chemotherapy, local-field radiation, or participation in a clinical trial.

In the case of multiple or bilateral ILNs, patients should undergo a fine-needle aspiration of the lymph nodes regardless of whether these are mobile or fixed. A negative result should be confirmed with excisional biopsy. If results are again negative, the patient should be closely followed. Patients with a positive aspiration or biopsy should be managed the same as those with enlarged PLNs.

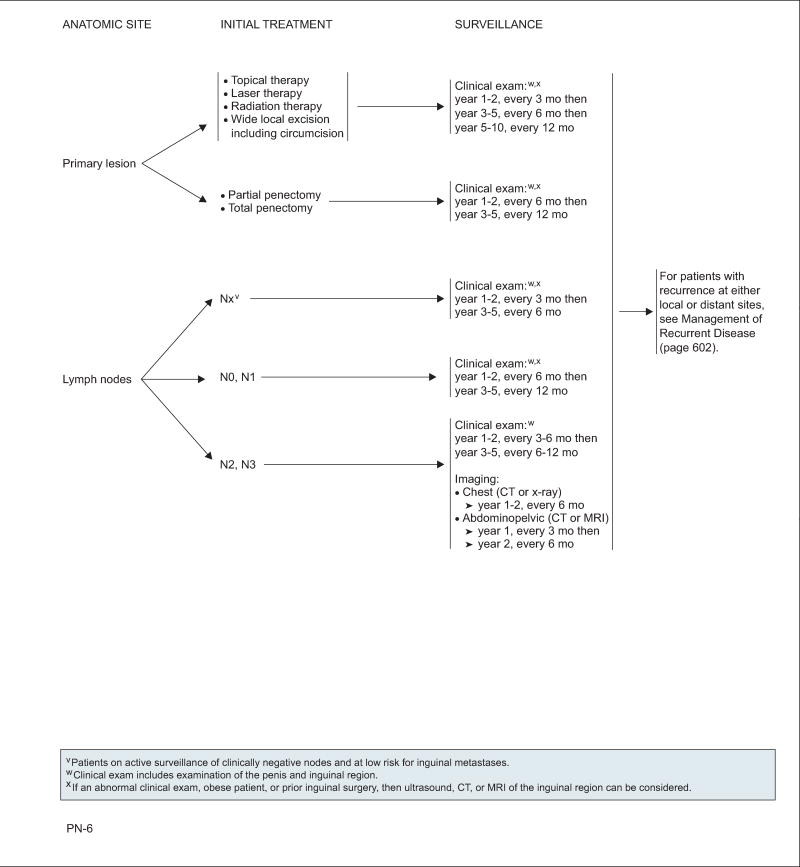

Surveillance

Initial treatment of the primary tumor and lymph nodes dictates the follow-up schedule (see algorithm, pages 596–605). A large retrospective review of 700 patients found that penile-sparing therapies carry a significantly higher risk of local recurrence (28%) than partial or total penectomy (5%) and thus require closer surveillance.96 Patients without nodal involvement had a regional recurrence rate of 2% compared with 19% for patients with N+ disease. Of all recurrences, 92% were detected within 5 years of primary treatment.

Follow-up for all patients includes a clinical examination of the penis and inguinal region. Imaging is not routinely indicated for early disease (except for patients who are obese or who have undergone inguinal surgery, because physical examination may be challenging), but may be used on abnormal findings. For patients with N2 or N3 disease, imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvic area is recommended.

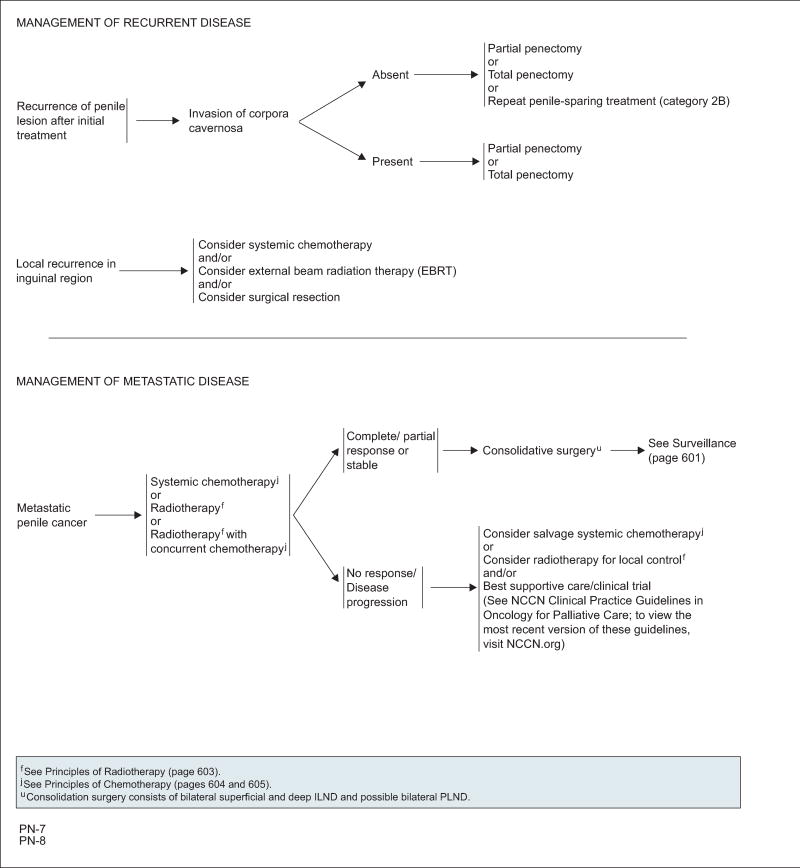

Recurrence

Invasion of the corpora cavernosa is an adverse finding after initial organ-sparing treatment that warrants partial or total penectomy.97,98 For primary tumor recurrences without corpora cavernosa infiltration, salvage penile-sparing options can be considered (category 2B).

A recurrence in the inguinal region carries a poor prognosis (median survival <6 months), and optimal management remains elusive. Possible salvage options include systemic chemotherapy, EBRT, surgery, or a combination thereof.50,99

Metastatic Disease

Imaging of the abdomen and pelvis should be obtained when metastasis is suspected to evaluate for pelvic and/or retroperitoneal lymph nodes. PLN metastases is an ominous finding, with a 5-year survival rate of 0% to 66% for all cases and 17% to 54% for microscopic invasion only, with the mean 5-year survival being approximately 10%.4,100–104 In patients with ILN metastases, 20% to 30% will have PLN metastases.4 This can be further characterized such that if 2 to 3 ILNs are involved, there is a 23% probability of PLN involvement. With 3 or more ILNs this probability increases to 56%.105

Pettaway et al106 evaluated the treatment options for stage IV penile cancer—clinical stage N3 (deep inguinal nodes or pelvic nodes) or M1 disease (distant metastases)—including chemotherapy, RT, and inguinal lymphadenectomy. Cisplatin-based regimens (paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin or, alternatively, 5-FU plus cisplatin) are the most active first-line systemic chemotherapy regimens. The panel did not recommend regimens containing bleomycin because of high toxicity. Those patients with a proven objective response to systemic chemotherapy are amenable to consolidative ILND with curative potential or palliation. However, surgical consolidation should not be performed on patients who experience progression during systemic chemotherapy, except to provide local symptomatic control. Preoperative RT may also be given to patients who have lymph nodes 4 cm or greater without skin fixation to improve surgical resectability and decrease local recurrence. For patients with unresectable inguinal or bone metastases, RT may provide a palliative benefit after chemotherapy. Salvage systemic chemotherapy may also be considered on disease progression. Best supportive care remains an option for these advanced cases.

Summary

SCC of the penis is a disease that mandates prompt medical/surgical intervention and patient compliance to obtain the most favorable outcomes. A thorough history and physical is the initial step in this process, followed by a biopsy of the primary lesion to establish a pathologic diagnosis. Accurate clinical staging allows for a comprehensive treatment approach to be devised, thus optimizing therapeutic efficacy and minimizing treatment-related morbidity. Prognostic factors help predict whether lymph node metastases are suspect in the absence of any palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy. When clinically indicated, an ILND has curative potential, particularly when performed early, with contemporary surgical series showing its reduced morbidity.

NCCN Penile Cancer Panel Members

*Peter E. Clark, MD/Chairω

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

Neeraj Agarwal, MD‡

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

Matthew C. Biagioli, MD, MS§

Moffitt Cancer Center

Mario A. Eisenberger, MD†ω

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins

Richard E. Greenberg, MDω

Fox Chase Cancer Center

Harry W. Herr, MDω

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Brant A. Inman, MD, MScω

Duke Cancer Institute

Deborah A. Kuban, MD§

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Timothy M. Kuzel, MD‡

Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

Subodh M. Lele, MD≠

UNMC Eppley Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

Jeff Michalski, MD, MBA§

Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine

Lance C. Pagliaro, MD†

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Sumanta K. Pal, MD†

City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center

Anthony Patterson, MDω

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/ The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

*Elizabeth R. Plimack, MD, MS†

Fox Chase Cancer Center

Kamal S. Pohar, MDw

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute

Michael P. Porter, MD, MSω

University of Washington/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

Jerome P. Richie, MDω

Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

Wade J. Sexton, MDω

Moffitt Cancer Center

*William U. Shipley, MD§ω

Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center

Eric J. Small, MD†ω

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

Philippe E. Spiess, MD, MSω

Moffitt Cancer Center

Donald L. Trump, MD†

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

Geoffrey Wile, MD

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

Timothy G. Wilson, MDω

City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center

NCCN Staff: Mary Dwyer, MS, and Maria Ho, PhD

KEY:

*Writing Committee Member

Specialties: ωUrology; ≠Pathology; †Medical Oncology; ‡Hematology/Hematology Oncology; §Radiotherapy/ Radiation Oncology

Footnotes

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way.

© National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2013, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines and the illustrations herein may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Disclosures for the NCCN Penile Cancer Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines panel meeting, panel members review all potential conflicts of interest. NCCN, in keeping with its commitment to public transparency, publishes these disclosures for panel members, staff, and NCCN itself.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Penile Cancer Panel members can be found on page 615. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures are available on the NCCN Web site at NCCN.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, visit NCCN.org.

References

- 1.Pettaway CA, Lynch D, Jr, Davis D. Tumors of the penis. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi L, Novick AC, et al., editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 959–992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pow-Sang MR, Ferreira U, Pow-Sang JM, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of penile cancer. Urology. 2010;76:S2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horenblas S. Lymphadenectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Part 2: the role and technique of lymph node dissection. BJU Int. 2001;88:473–483. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez BY, Barnholtz-Sloan J, German RR, et al. Burden of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008;113:2883–2891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillner J, von Krogh G, Horenblas S, Meijer CJ. Etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2000:189–193. doi: 10.1080/00365590050509913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sufrin G, Huben R. Benign and malignant lesions of the penis. In: Gillenwater JY, Grayhack JT, Howards SS, Duckett JW, editors. Adult and Pediatric Urology. 2. Chicago: Mosby Year Book Medical Publishers; 1991. pp. 1997–2042. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Penile cancer: importance of circumcision, human papillomavirus and smoking in in situ and invasive disease. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:606–616. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkar FH, Miles BJ, Plieth DH, Crissman JD. Detection of human papillomavirus in squamous neoplasm of the penis. J Urol. 1992;147:389–392. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980–2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645–1654. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238411.75324.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maden C, Sherman KJ, Beckmann AM, et al. History of circumcision, medical conditions, and sexual activity and risk of penile cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:19–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Depasquale I, Park AJ, Bracka A. The treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans. BJU Int. 2000;86:459–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Micali G, Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Schwartz RA. Penile cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:369–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Mirri F, et al. Penile carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus: a multicenter survey. J Urol. 2006;175:1359–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern RS. Genital tumors among men with psoriasis exposed to psoralens and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) and ultraviolet B radiation. The Photochemotherapy Follow-up Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1093–1097. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004193221601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleeker MC, Heideman DA, Snijders PJ, et al. Penile cancer: epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention. World J Urol. 2009;27:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0302-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cubilla AL, Reuter V, Velazquez E, et al. Histologic classification of penile carcinoma and its relation to outcome in 61 patients with primary resection. Int J Surg Pathol. 2001;9:111–120. doi: 10.1177/106689690100900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guimaraes GC, Cunha IW, Soares FA, et al. Penile squamous cell carcinoma clinicopathological features, nodal metastasis and outcome in 333 cases. J Urol. 2009;182:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ficarra V, Akduman B, Bouchot O, et al. Prognostic factors in penile cancer. Urology. 2010;76:S66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barocas DA, Chang SS. Penile cancer: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging. Urol Clin North Am. 2010;37:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leijte JA, Gallee M, Antonini N, Horenblas S. Evaluation of current TNM classification of penile carcinoma. J Urol. 2008;180:933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leijte JA, Horenblas S. Shortcomings of the current TNM classification for penile carcinoma: time for a change? World J Urol. 2009;27:151–154. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobin LH, Wittekind C International Union against Cancer. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 6. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slaton JW, Morgenstern N, Levy DA, et al. Tumor stage, vascular invasion and the percentage of poorly differentiated cancer: independent prognosticators for inguinal lymph node metastasis in penile squamous cancer. J Urol. 2001;165:1138–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velazquez EF, Ayala G, Liu H, et al. Histologic grade and perineural invasion are more important than tumor thickness as predictor of nodal metastasis in penile squamous cell carcinoma invading 5 to 10 mm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:974–979. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181641365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pizzocaro G, Algaba F, Horenblas S, et al. EAU penile cancer guidelines 2009. Eur Urol. 2010;57:1002–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lont AP, Besnard AP, Gallee MPW, et al. A comparison of physical examination and imaging in determining the extent of primary penile carcinoma. BJU Int. 2003;91:493–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. A case of erythroplasia of queyrat treated with imiquimod 5% cream and excision. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:419–422. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.4.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroeder TL, Sengelmann RD. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the penis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:545–548. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taliaferro SJ, Cohen GF. Bowen’s disease of the penis treated with topical imiquimod 5% cream. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:483–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldman AS, McDougal WS. Long-term outcome of excisional organ sparing surgery for carcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2011;186:1303–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandieramonte G, Colecchia M, Mariani L, et al. Peniscopically controlled CO2 laser excision for conservative treatment of in situ and T1 penile carcinoma: report on 224 patients. Eur Urol. 2008;54:875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horenblas S, van Tinteren H, Delemarre JF, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. II. Treatment of the primary tumor. J Urol. 1992;147:1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morelli G, Pagni R, Mariani C, et al. Glansectomy with split-thickness skin graft for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:311–314. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Kane HF, Pahuja A, Ho KJ, et al. Outcome of glansectomy and skin grafting in the management of penile cancer. Adv Urol. 2011;2011:240824. doi: 10.1155/2011/240824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pietrzak P, Corbishley C, Watkin N. Organ-sparing surgery for invasive penile cancer: early follow-up data. BJU Int. 2004;94:1253–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatzichristou DG, Apostolidis A, Tzortzis V, et al. Glansectomy: an alternative surgical treatment for Buschke-Lowenstein tumors of the penis. Urology. 2001;57:966–969. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00942-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bissada NK, Yakout HH, Fahmy WE, et al. Multi-institutional long-term experience with conservative surgery for invasive penile carcinoma. J Urol. 2003;169:500–502. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000043808.58188.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frimberger D, Hungerhuber E, Zaak D, et al. Penile carcinoma. Is Nd:YAG laser therapy radical enough? J Urol. 2002;168:2418–2421. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azrif M, Logue JP, Swindell R, et al. External-beam radiotherapy in T1-2 N0 penile carcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2006;18:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crook J, Grimard L, Tsihlias J, et al. Interstitial brachytherapy for penile cancer: an alternative to amputation. J Urol. 2002;167:506–511. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rozan R, Albuisson E, Giraud B, et al. Interstitial brachytherapy for penile carcinoma: a multicentric survey (259 patients) Radiother Oncol. 1995;36:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(95)01574-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zouhair A, Coucke PA, Jeanneret W, et al. Radiation therapy alone or combined surgery and radiation therapy in squamous-cell carcinoma of the penis? Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:198–203. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crook J, Ma C, Grimard L. Radiation therapy in the management of the primary penile tumor: an update. World J Urol. 2009;27:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horenblas S, van Tinteren H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. IV. Prognostic factors of survival: analysis of tumor, nodes and metastasis classification system. J Urol. 1994;151:1239–1243. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minhas S, Kayes O, Hegarty P, et al. What surgical resection margins are required to achieve oncological control in men with primary penile cancer? BJU Int. 2005;96:1040–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Crevoisier R, Slimane K, Sanfilippo N, et al. Long-term results of brachytherapy for carcinoma of the penis confined to the glans (N- or NX) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1150–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crook J, Jezioranski J, Cygler JE. Penile brachytherapy: technical aspects and postimplant issues. Brachytherapy. 2010;9:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heyns CF, Fleshner N, Sangar V, et al. Management of the lymph nodes in penile cancer. Urology. 2010;76:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solsona E, Algaba F, Horenblas S, et al. EAU Guidelines on Penile Cancer. Eur Urol. 2004;46:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kroon BK, Valdes Olmos RA, van Tinteren H, et al. Reproducibility of lymphoscintigraphy for lymphatic mapping in patients with penile carcinoma. J Urol. 2005;174:2214–2217. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181813.43631.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes B, Leijte J, Shabbir M, et al. Non-invasive and minimally invasive staging of regional lymph nodes in penile cancer. World J Urol. 2009;27:197–203. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mueller-Lisse UG, Scher B, Scherr MK, Seitz M. Functional imaging in penile cancer: PET/computed tomography, MRI, and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18:105–110. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282f151fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scher B, Seitz M, Albinger W, et al. Value of PET and PET/CT in the diagnostics of prostate and penile cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2008;170:159–179. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-31203-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scher B, Seitz M, Reiser M, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT for staging of penile cancer. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1460–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tabatabaei S, Harisinghani M, McDougal WS. Regional lymph node staging using lymphotropic nanoparticle enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with ferumoxtran-10 in patients with penile cancer. J Urol. 2005;174:923–927. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000170234.14519.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caso JR, Rodriguez AR, Correa J, Spiess PE. Update in the management of penile cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2009;35:406–415. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382009000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pizzocaro G, Piva L, Bandieramonte G, Tana S. Up-to-date management of carcinoma of the penis. Eur Urol. 1997;32:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solsona E, Iborra I, Rubio J, et al. Prospective validation of the association of local tumor stage and grade as a predictive factor for occult lymph node micrometastasis in patients with penile carcinoma and clinically negative inguinal lymph nodes. J Urol. 2001;165:1506–1509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villavicencio H, Rubio-Briones J, Regalado R, et al. Grade, local stage and growth pattern as prognostic factors in carcinoma of the penis. Eur Urol. 1997;32:442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cabanas RM. An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer. 1977;39:456–466. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197702)39:2<456::aid-cncr2820390214>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pettaway CA, Pisters LL, Dinney CP, et al. Sentinel lymph node dissection for penile carcinoma: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. J Urol. 1995;154:1999–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leijte JA, Kroon BK, Valdes Olmos RA, et al. Reliability and safety of current dynamic sentinel node biopsy for penile carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2007;52:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Valdes Olmos RA, Tanis PJ, Hoefnagel CA, et al. Penile lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel node identification. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:581–585. doi: 10.1007/s002590100476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonzaga-Silva LF, Tavares JM, Freitas FC, et al. The isolated gamma probe technique for sentinel node penile carcinoma detection is unreliable. Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33:58–63. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382007000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kroon BK, Horenblas S, Meinhardt W, et al. Dynamic sentinel node biopsy in penile carcinoma: evaluation of 10 years experience. Eur Urol. 2005;47:601–606. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spiess PE, Izawa JI, Bassett R, et al. Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and dynamic sentinel node biopsy for staging penile cancer: results with pathological correlation. J Urol. 2007;177:2157–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tanis PJ, Lont AP, Meinhardt W, et al. Dynamic sentinel node biopsy for penile cancer: reliability of a staging technique. J Urol. 2002;168:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kroon BK, Horenblas S, Estourgie SH, et al. How to avoid false-negative dynamic sentinel node procedures in penile carcinoma. J Urol. 2004;171:2191–2194. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000124485.34430.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kroon BK, Horenblas S, Deurloo EE, et al. Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology before sentinel node biopsy in patients with penile carcinoma. BJU Int. 2005;95:517–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crawshaw JW, Hadway P, Hoffland D, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy using dynamic lymphoscintigraphy combined with ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in penile carcinoma. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:41–48. doi: 10.1259/bjr/99732265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hadway P, Smith Y, Corbishley C, et al. Evaluation of dynamic lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph-node biopsy for detecting occult metastases in patients with penile squamous cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2007;100:561–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ficarra V, Galfano A. Should the dynamic sentinel node biopsy (DSNB) be considered the gold standard in the evaluation of lymph node status in patients with penile carcinoma? Eur Urol. 2007;52:17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stancik I, Holtl W. Penile cancer: review of the recent literature. Curr Opin Urol. 2003;13:467–472. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000098068.73234.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kroon BK, Horenblas S, Lont AP, et al. Patients with penile carcinoma benefit from immediate resection of clinically occult lymph node metastases. J Urol. 2005;173:816–819. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154565.37397.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McDougal WS. Preemptive lymphadenectomy markedly improves survival in patients with cancer of the penis who harbor occult metastases. J Urol. 2005;173:681. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000153484.07200.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sharp DS, Angermeier KW. Surgery of penile and urethral carcinoma. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi L, Novick AC, et al., editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Catalona WJ. Re: Modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the penis with preservation of saphenous veins: technique and preliminary results. J Urol. 1988;140:836. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41838-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lopes A, Rossi BM, Fonseca FP, Morini S. Unreliability of modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for clinical staging of penile carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77:2099–2102. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960515)77:10<2099::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Protzel C, Alcaraz A, Horenblas S, et al. Lymphadenectomy in the surgical management of penile cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1075–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bermejo C, Busby JE, Spiess PE, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by aggressive surgical consolidation for metastatic penile squamous cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177:1335–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pagliaro LC, Crook J. Multimodality therapy in penile cancer: when and which treatments? World J Urol. 2009;27:221–225. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spiess PE, Hernandez MS, Pettaway CA. Contemporary inguinal lymph node dissection: minimizing complications. World J Urol. 2009;27:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lont AP, Kroon BK, Gallee MP, et al. Pelvic lymph node dissection for penile carcinoma: extent of inguinal lymph node involvement as an indicator for pelvic lymph node involvement and survival. J Urol. 2007;177:947–952. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tobias-Machado M, Tavares A, Molina WR, et al. Video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy (VEIL): minimally invasive resection of inguinal lymph nodes. Int Braz J Urol. 2006;32:316–321. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382006000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tobias-Machado M, Tavares A, Ornellas AA, et al. Video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy: a new minimally invasive procedure for radical management of inguinal nodes in patients with penile squamous cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177:953–957. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tobias-Machado M, Tavares A, Silva MN, et al. Can video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy achieve a lower morbidity than open lymph node dissection in penile cancer patients? J Endourol. 2008;22:1687–1691. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bishoff JT, Lackland AF, Basler JW, et al. Endoscopic subcutaneous modified inguinal lymph node dissection (ESMIL) for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003;169(Suppl):78. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sotelo R, Sanchez-Salas R, Carmona O, et al. Endoscopic lymphadenectomy for penile carcinoma. J Endourol. 2007;21:364–367. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.9971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haas GP, Blumenstein BA, Gagliano RG, et al. Cisplatin, methotrexate and bleomycin for the treatment of carcinoma of the penis: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Urol. 1999;161:1823–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pagliaro LC, Williams DL, Daliani D, et al. Neoadjuvant paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin chemotherapy for metastatic penile cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3851–3857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Theodorescu D, Russo P, Zhang ZF, et al. Outcomes of initial surveillance of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis and negative nodes. J Urol. 1996;155:1626–1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leijte JA, Hughes B, Graafland NM, et al. Two-center evaluation of dynamic sentinel node biopsy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3325–3329. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lont AP, Horenblas S, Tanis PJ, et al. Management of clinically node negative penile carcinoma: improved survival after the introduction of dynamic sentinel node biopsy. J Urol. 2003;170:783–786. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000081201.40365.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leijte JA, Kirrander P, Antonini N, et al. Recurrence patterns of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: recommendations for follow-up based on a two-centre analysis of 700 patients. Eur Urol. 2008;54:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chaux A, Reuter V, Lezcano C, et al. Comparison of morphologic features and outcome of resected recurrent and nonrecurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: a study of 81 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1299–1306. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a418ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ornellas AA, Nobrega BL, Wei Kin Chin E, et al. Prognostic factors in invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: analysis of 196 patients treated at the Brazilian National Cancer Institute. J Urol. 2008;180:1354–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Graafland NM, Moonen LM, van Boven HH, et al. Inguinal recurrence following therapeutic lymphadenectomy for node positive penile carcinoma: outcome and implications for management. J Urol. 2011;185:888–893. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lopes A, Bezerra AL, Serrano SV, Hidalgo GS. Iliac nodal metastases from carcinoma of the penis treated surgically. BJU Int. 2000;86:690–693. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pow-Sang JE, Benavente V, Pow-Sang JM, Pow-Sang M. Bilateral ilioinguinal lymph node dissection in the management of cancer of the penis. Semin Surg Oncol. 1990;6:241–242. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980060411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ravi R. Morbidity following groin dissection for penile carcinoma. Br J Urol. 1993;72:941–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sanchez-Ortiz RF, Pettaway CA. The role of lymphadenectomy in penile cancer. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Srinivas V, Morse MJ, Herr HW, et al. Penile cancer: relation of extent of nodal metastasis to survival. J Urol. 1987;137:880–882. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Culkin DJ, Beer TM. Advanced penile carcinoma. J Urol. 2003;170:359–365. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000062829.43654.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pettaway CA, Pagliaro L, Theodore C, Haas G. Treatment of visceral, unresectable, or bulky/unresectable regional metastases of penile cancer. Urology. 2010;76:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]