Abstract

The novel therapies thalidomide and bortezomib can cause peripheral neuropathy, a challenging adverse event that can affect quality of life and compromise optimal treatment for patients with multiple myeloma. At baseline, patients should be evaluated for signs and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy with a neurotoxicity assessment tool and educated about the symptoms and the importance of reporting them. Signs, symptoms, and the ability to perform activities of daily living should be evaluated regularly so that appropriate interventions can be employed if necessary. Specific management strategies for peripheral neuropathy are based on the grade of severity and on signs and symptoms; strategies include dose and schedule modifications, pharmacologic interventions, nonpharmacologic approaches, and patient education.

Novel therapies for multiple myeloma include the immunomodulatory drugs lenalidomide (Revlimid®, Celgene Corporation) and thalidomide (Thalomid®, Celgene Corporation) and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade®, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). The benefits of the agents for patients with multiple myeloma include increased response rates and longer survival times compared with conventional chemotherapy (Celgene Corporation, 2007a, 2007b; Ghobrial et al., 2007; Manochakian, Miller, & Chanan-Khan, 2007; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2007; Rajkumar et al., 2005; Richardson & Anderson, 2006; Richardson, Hideshima, Mitsiades, & Anderson, 2007). Two of the agents, thalidomide and bortezomib, are associated with the development of peripheral neuropathy, a side effect that can seriously affect quality of life and interfere with optimal treatment. Although rare, peripheral neuropathy can be life threatening, which can lead to serious medical conditions such as irregular heartbeat, hypotension, and shortness of breath (Armstrong, Almadrones, & Gilbert, 2005; Marrs & Newton, 2003; Shah, et al., 2004; Singhal & Mehta, 2001; Sweeney, 2002; Wickham, 2007).

The International Myeloma Foundation’s Nurse Leadership Board, in recognition of the need for specific recommendations on managing key side effects of novel antimyeloma agents, developed this consensus statement for the management of peripheral neuropathy associated with thalidomide and bortezomib (Bertolotti et al., 2007, 2008). It was developed for use by health-care providers in any type of medical setting. The recommendations outlined in this article, developed through evidence-based reviews and the consensus of the Nurse Leadership Board, are applicable for managing peripheral neuropathy.

Issue Statement

Peripheral neuropathy describes damage to the peripheral nervous system. Any injury, inflammation, or degeneration of peripheral nerve fibers can lead to peripheral neuropathy. The impaired function and symptoms depend on the type of nerves affected, which can be motor, sensory, or autonomic nerve fibers. Peripheral neuropathy can manifest as temporary numbness, tingling, paresthesias (pricking sensations), sensitivity to touch, or muscle weakness. Peripheral neuropathy also can cause more severe symptoms, such as burning pain, muscle wasting, paralysis, or organ dysfunction, and may adversely affect digestion, maintenance of blood pressure, and other bodily functions; in extreme cases, it can affect breathing and lead to organ failure (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [NINDS], 2007). The symptoms are related to possible damage to the autonomic nerves that control heart rate, blood pressure, and digestion, among other functions. Additional investigation is warranted to clarify the possible association of autonomic neuropathy with bortezomib (Orlowski et al., 2002; Shah et al., 2004) and thalidomide (Fahdi et al., 2004; Singhal & Mehta, 2001). Symptoms such as bradycardia or irregular heartbeat while on thalidomide or hypotension while on bortezomib therapy may indicate autonomic chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

Peripheral neuropathy associated with multiple myeloma is a well-known entity (Dispenzieri & Kyle, 2005). The incidence of clinically apparent peripheral neuropathy at diagnosis in patients with multiple myeloma has been reported to be less than 1%, 2%, or as high as 13% (Dispenzieri & Kyle, 2005; Plasmati et al., 2007; Ropper & Gorson, 1998). When comprehensive neurologic examination with electrophysiologic testing was performed in previously untreated patients with multiple myeloma, small-fiber neuropathy was found in 52% and large-fiber axonal neuropathy occurred in 9% of patients; the rate of electrophysiologic evidence of peripheral neuropathy has been reported as 39% (Anderson et al., 2006; Dispenzieri & Kyle). Peripheral neuropathy is a late complication in most patients with multiple myeloma. More than 80% of patients with multiple myeloma in the phase II trial of bortezomib who had received multiple prior therapies, but not prior bortezomib, had baseline peripheral neuropathy by neurologic examination (Richardson, Briemberg, et al., 2006).

Peripheral neuropathy in patients with multiple myeloma is usually axonal, mixed sensorimotor; symptoms are symmetrical, distal, and progressive. The exact mechanism of the neuropathy in newly diagnosed myeloma is unknown but may be related to the paraprotein, weight loss, metabolic, or toxic factors associated with the malignancy (Tariman, 2005). Amyloidosis frequently is present in patients with multiple myeloma who have peripheral neuropathy, and deposition of amyloid damages nerves (Dispenzieri & Kyle, 2005; Ropper & Gorson, 1998).

Since the late 1990s, peripheral neuropathy has emerged as one of the most challenging and dose-limiting side effects associated with novel therapies for multiple myeloma, such as thalidomide and bortezomib. The incidence of therapy-induced peripheral sensory and motor neuropathy reported in the registration trial in patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma was 54% for all grades of severity. Thalidomide-associated peripheral neuropathy generally occurs following chronic therapy but may result from relatively short-term therapy and may be irreversible (Celgene Corporation, 2007b). In one group of patients, the severity of thalidomide-associated neuropathy appeared to be related to the duration of disease prior to treatment rather than the cumulative or daily dose of the drug (Tosi et al., 2005). Other investigators believe that the severity of peripheral neuropathy is related to higher cumulative dose of thalidomide and treatment duration (Mileshkin et al., 2006).

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy in patients receiving single-agent bortezomib in the phase III registration trial who had received other prior therapies was 36% for all grades of severity (Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2007). Bortezomib-associated peripheral neuropathy was found to be partially to fully reversible in most patients after dose modification or treatment discontinuation, but resolution of neuropathy could take as long as 48 weeks (Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Richardson, Briemberg, et al., 2006, 2007).

To date, the reported incidence of lenalidomide-associated peripheral neuropathy is low (2%–3%) (Celgene Corporation, 2007a; Richardson, Blood, et al., 2006; Weber et al., 2007).

All three novel therapies have been available for a relatively short time. How long-term exposures and cumulative doses may correlate with the development or reversibility of peripheral neuropathy for patients on long-term or maintenance therapy is unclear.

The Nurse Leadership Board’s Position on Peripheral Neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy has a significant impact on quality of life, including the physical, social, and psychological effects of unrelieved neuropathic pain.

Healthcare professionals, primarily nurses, should address peripheral neuropathy associated with thalidomide and bortezomib in a timely manner. Patients should be counseled and evaluated regularly for signs and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy.

Patients’ physical examination should include neurologic assessment with a neurotoxicity assessment tool (described later) at baseline, at the onset of worsening neuropathy, and at each consecutive encounter when clinically indicated, particularly while on therapy with thalidomide or bortezomib.

Patients should be examined at monthly intervals for the first three months of thalidomide therapy to detect early signs of neuropathy (e.g., numbness, tingling, pain in the hands and feet) and should be evaluated periodically thereafter during treatment. Electrophysiologic testing to measure sensory nerve action potential amplitudes at baseline and thereafter at six-month intervals should be considered for detection of asymptomatic neuropathy, which, if present, requires immediate discontinuation of thalidomide therapy (Celgene Corporation, 2007b).

Clinicians are responsible for integrating patient education concerning side effects, particularly early reporting of peripheral neuropathy, to avoid irreversible peripheral nerve damage.

Nurses should evaluate patients’ abilities to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) (e.g., dressing and feeding themselves) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), defined as secondary activities related to independent living and safety issues at home (e.g., avoiding injuries, falls, and burns that can result from decreased ability to sense objects in the environment or their temperatures). Nurses should employ interventions such as home healthcare services in patients with peripheral neuropathy that interferes with ADLs or IADLs.

Interdisciplinary management of peripheral neuropathy based on available resources (e.g., pain service, neurology service, psychosocial service, physical therapy) is highly encouraged.

Nurses and cancer treatment facilities should adopt policies that facilitate interdisciplinary trials addressing neuropathy management.

Nurses should use adult verbal or nonverbal pain scales to assess neuropathic pain and follow pain management guidelines: the American Cancer Society (ACS) Pain Management Pocket Tool (ACS, 2005), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™ for adult cancer pain (NCCN, 2007), and the NCCN and ACS cancer pain treatment guidelines for patients (NCCN & ACS, 2005).

Adequate management of peripheral neuropathy will increase mobility and promote patient safety, increase therapy adherence, increase self-esteem, prevent unnecessary pain and discomfort, prevent muscle wasting, and improve quality of life (Colson, Doss, Swift, Tariman, & Thomas, 2004; Doss, 2006; Lonial, 2007; Tariman, 2005).

Toxicity Tools for Grading and Management

The severity of neuropathy, including adverse events related to neuropathic pain, can be quantified with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). The NCI CTCAE are used for identifying treatment-related adverse events to facilitate the evaluation of new cancer therapies, treatment modalities, and supportive measures. For most adverse events, the NCI CTCAE define grades 1–5 using unique clinical descriptions; each grade is assigned a severity: grade 1 is mild, grade 2 is moderate, grade 3 is severe, grade 4 is life threatening or disabling, and grade 5 defines death related to the adverse event. The grades may be used for monitoring neuropathy and determining the need for intervention. Under the NCI CTCAE version 3.0 category of neurology, neuropathic pain is graded as pain in the pain category. Table 1 defines the NCI CTCAE version 3.0 pain toxicity grades 1–4. Other types of neuropathies may be associated with the novel therapies, including motor and sensory neuropathies. They are graded in the CTCAE neurology category. In the pain category, no grade 5 toxicity (death) exists; however, both sensory and motor neuropathy can result in death (NCI, 2006).

Table 1.

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: Neuropathy and Paina

| ADVERSE EVENT | GRADE 1 (MILD) | GRADE 2 (MODERATE) | GRADE 3 (SEVERE) | GRADE 4 (LIFE THREATENING OR DISABLING) | GRADE 5 (DEATH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain in a specific body system (e.g., extremity) | Mild pain not interfering with function | Moderate pain; pain or analgesics interfering with function but not interfering with activities of daily living | Severe pain; pain or analgesics severely interfering with activities of daily living | Disabling | Not applicable |

| Neuropathy: motorb | Asymptomatic; weakness on examination or testing only | Symptomatic weakness interfering with function but not interfering with activities of daily living | Weakness interfering with activities of daily living; bracing or assistance to walk (e.g., cane, walker) indicated | Life threatening or disabling (e.g., paralysis) | Death |

| Neuropathy: sensoryb | Asymptomatic; loss of deep tendon reflexes or paresthesias (including tingling) but not interfering with function | Sensory alteration or paresthesias (including tingling) interfering with function but not with activities of daily living | Sensory alteration or paresthesias interfering with activities of daily living | Disabling | Death |

Neuropathic pain is graded as pain.

Cranial nerve motor or sensory neuropathy is graded as “Neuropathy: cranial” or “Neuropathy: sensory,” respectively.

Note. Based on information from National Cancer Institute, 2006.

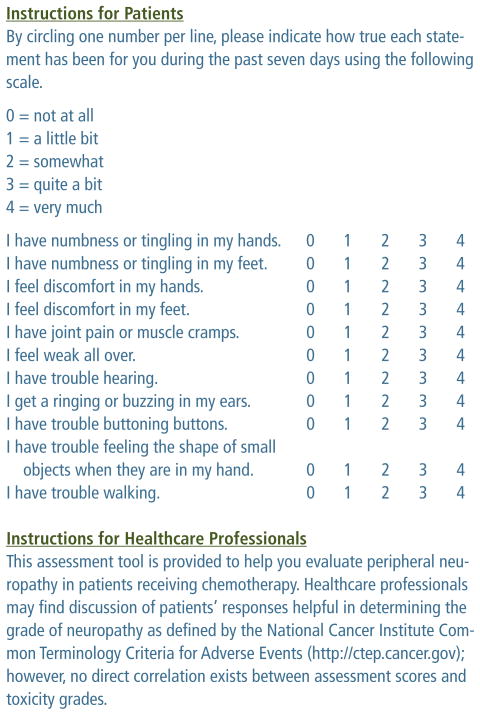

Neurotoxicity Assessment Tool

Figure 1 shows a neurotoxicity assessment tool that can be used by healthcare providers to assess peripheral neuropathy in their patients, including those with multiple myeloma. Healthcare providers can discuss with patients their responses to the questions in the assessment tool to determine the CTCAE grade of any neurotoxicities they are experiencing, although the assessment scores do not correlate with CTCAE toxicity grades (Cavaletti et al., 2003; Cella et al., 1993; Cornblath et al., 1999; NCI, 2006).

Figure 1.

Neurotoxicity Assessment Tool

Note. Based on information from Calhoun et al., 2000; Cella, 1997; Cella et al., 1993.

Management of Peripheral Neuropathy

All patients should receive a baseline assessment with the neurotoxicity assessment tool prior to initiating therapy with thalidomide or bortezomib. Although patients with multiple myeloma can present with neuropathy at diagnosis, the neuropathy can be the result of other comorbidities, such as diabetes, amyloidosis, or HIV infection (NINDS, 2007). At baseline, patients should receive education about the symptoms of peripheral neuropathy and the importance of reporting the symptoms to their healthcare providers.

The following supplements, based on anecdotal evidence at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, also are recommended: B-complex vitamins, including B1, B6, and B12 (at least 400 mcg); and folic acid 1 mg daily (Colson et al., 2004). Further investigation is warranted to determine the efficacy of the supplements.

Specific recommendations for the management of peripheral neuropathy, if and when it occurs, are based on the grade of severity and the associated signs and symptoms. Table 2 describes management strategies for patients taking thalidomide, and Table 3 describes management strategies for patients taking bortezomib. The strategies include recommendations for dose and schedule modifications, pharmacologic interventions, non-pharmacologic approaches, and education. Painful neuropathy is not as common with thalidomide as with bortezomib, so the pain management strategies are less likely to be needed for patients taking thalidomide.

Table 2.

Management of Peripheral Neuropathy Associated With Thalidomide Therapy

| TOXICITYGRADEa OR SYMPTOMS |

EXAMINATIONS | DOSE AND SCHEDULE MODIFICATIONS |

PHARMACEUTICAL INTERVENTIONS |

NONPHARMACEUTICAL APPROACHES |

EDUCATION RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (mild) | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool | Continue therapy. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Educate patient to notify clinicians immediately if peripheral neuropathy worsens. |

| Grade 2 (moderate) | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool | If symptoms are intermittent, continue therapy; if they are continuous, stop therapy and observe whether symptoms persist. If symptoms resolve, restart therapy at a reduced dose. | Consider tricyclic antidepressants; may try amino acidsb (e.g., acetyl L-carnitine, L-glutamine, alpha-lipoic acid on an empty stomach) | For intermittent symptoms, gentle massage of affected areas with cocoa butter or capsaicin cream | Educate patient to notify clinicians immediately if peripheral neuropathy worsens. |

| Grade 3 (severe) | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool; nerve conduction studies | Hold therapy until peripheral neuropathy resolves to baseline. If symptoms resolve, restart therapy at a reduced dose. | Make certain patient is on amino acidsb (e.g., acetyl L-carnitine, L-glutamine, alpha-lipoic acid on an empty stomach). Consider using gabapentin, pregabalin, duloxetine hydrochloride, or tricyclic antidepressants. May apply lidocaine patch 5% to affected area every 12 hoursc | Arrange for a home health referral to review safety at home. Assess needs for assistance with activities of daily living. | Provide education on decreased sensation in extremities and safety issues. Family members must assess hot and cold temperatures if patient is unable to do so. |

| Grade 4 (life threatening or disabling) | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool | Discontinue therapy permanently. | Consider using gaba-pentin, pregabalin, duloxetine hydrochloride, or tricyclic antide-pressants. May apply lidocaine patch 5% to affected area every 12 hoursc | Refer patient for pain management and neurology consultation. Assess needs for assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. Refer to physical therapy or occupational therapy. | Provide education on decreased sensation in extremities and safety issues. Family members must assess hot and cold temperatures if patient is unable to do so. |

Grades per National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (National Cancer Institute, 2006)

Suggested doses: acetyl-L-carnitine 1 g IV for 10 consecutive days or 1 g PO three times a day for eight weeks; alpha-lipoic acid: 600 mg per day IV five days a week for three weeks; glutamine: 10 mg PO three times a day 24 hours after chemotherapy for four days (Visovsky et al., 2007)

Refer to patient instructions (Endo Pharmaceuticals, 2006).

Table 3.

Management of Peripheral Neuropathy Associated With Bortezomib Therapy

| TOXICITY GRADEa OR SYMPTOMS | EXAMINATIONS | DOSE AND SCHEDULE MODIFICATIONS | PHARMACEUTICAL INTERVENTIONS | NONPHARMACEUTICAL APPROACHES | EDUCATION RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (mild) | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool. Assess peripheral neuropathy before each dose of bortezomib. | Continue therapy | Not applicable | Not applicable | Educate patient to notify clinicians immediately if peripheral neuropathy worsens. |

| Grade 1 with pain or grade 2 | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool | Reduce dose to 1 mg/m2 | Consider starting gaba-pentin or pregabalin. May try amino acidsb (e.g., acetyl L-carnitine, alpha-lipoic acid with food). May apply lidocaine patch 5% to affected area every 12 hoursc. | For intermittent symptoms, gentle massage of affected areas with cocoa butter | Educate patient to notify clinicians immediately if peripheral neuropathy worsens. |

| Grade 3 (severe) | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool; nerve conduction studies | Hold therapy until peripheral neuropathy resolves to baseline, then restart at 0.7 mg/m2; consider changing treatment schedule to once per weekd. | Start gabapentin, pregabalin, duloxetine hydrochloride, or tricyclic antidepressants. | Arrange for a home health referral to review safety at home. Assess need for assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. | Educate about decreased sensation in extremities and safety issues at home such as poor lighting and loose rugs. Patient should avoid driving. Family members must assess hot and cold temperatures if patient is unable to do so. |

| Grade 4 (life threatening or disabling) | Nerve sensory examination of extremities using neurotoxicity assessment tool; nerve conduction studies | Discontinue therapy. | Not applicable | Refer patient for pain management and neurology consultation. Refer to physical therapy or occupational therapy. Assess needs for assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. | Educate about decreased sensation in extremities and safety issues at home such as poor lighting and loose rugs. Patient should avoid driving. Family members must assess hot and cold temperatures if patient is unable to do so. |

Grades per National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (National Cancer Institute, 2006)

Suggested doses: acetyl-L-carnitine 1 g IV for 10 consecutive days or 1 g PO three times a day for eight weeks or 500 mg twice a day increasing to as much as 2,000 mg per day as tolerated; alpha-lipoic acid 600 mg/day IV five days a week for three weeks or 300–1,000 mg a day with food; glutamine 10 mg PO three times a day 24 hours after chemotherapy for four days (Colson et al., 2004; Visovsky et al., 2007)

Refer to patient instructions (Endo Pharmaceuticals, 2006).

No evidence exists for the efficacy of this regimen.

Patients receiving thalidomide should be examined at monthly intervals for the first three months of therapy to detect early signs of neuropathy (e.g., numbness, tingling, pain in the hands and feet) and should be evaluated periodically thereafter during treatment. Electrophysiologic testing to measure sensory nerve action potential amplitudes at baseline and thereafter at six-month intervals should be considered for detection of asymptomatic neuropathy. If asymptomatic neuropathy is present, thalidomide should be discontinued immediately and reinitiated only if neuropathy returns to baseline status. Medications known to be associated with neuropathy, such as cisplatin and vincristine, should be used with caution or avoided if possible in patients receiving thalidomide (Celgene Corporation, 2007b).

Conclusions

Patients with multiple myeloma are at risk for developing peripheral neuropathy from their disease, its treatment, and co-morbid conditions. In addition to thalidomide and bortezomib, many conventional chemotherapy agents that patients with multiple myeloma may receive can cause peripheral neuropathy. Therefore, healthcare professionals must monitor patients closely for the adverse effect so that patient care and treatment can be managed effectively. This will result in more effective treatment and better quality of life (Lonial, 2007). The Oncology Nursing Society position on cancer pain management states that all patients with cancer have a right to pain prevention and management and that all healthcare professionals are accountable for effective pain management (Oncology Nursing Society, 2004). The recommendations presented in this article will help achieve those goals.

At a Glance.

The novel agents thalidomide and bortezomib can cause peripheral neuropathy, a challenging adverse event that can affect quality of life and compromise optimal treatment for patients with multiple myeloma.

Patients should be evaluated for signs and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy with a neurotoxicity assessment tool at baseline and periodically reassessed during treatment.

Management strategies include dose and schedule modifications, pharmacologic interventions, nonpharmacologic approaches, and patient education.

Patient Education Sheet: Preventing Peripheral Neuropathy From Novel Agents for Multiple Myeloma.

KEY POINTS

Peripheral neuropathy is a change in feeling in the arms, hands, fingers, legs, feet, toes, or other body parts. It can be a symptom of multiple myeloma or related to the use of medications to treat myeloma, such as novel therapies thalidomide and bortezomib. Managing peripheral neuropathy can reduce pain and other symptoms and can allow you to receive the best treatment for your myeloma. Your healthcare provider may change your dose or medication schedule to help manage your symptoms.

SYMPTOMS OF PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY

You may have the following symptoms in toes and feet, fingers and hands, or lips.

Numbness

Tingling

Burning pain

Muscle weakness

Sensitivity to touch

Prickling sensations

Sensation of cold in feet

Always report symptoms early to your healthcare team.

You may have an examination before treatment and at various times during treatment to see whether you have any symptoms of neuropathy. It is important to know when neuropathy affects your daily activities.

Two types of neuropathies exist: sensory and motor. The symptoms you should monitor and report to your healthcare provider are as follows.

-

Sensory

Tingling, numbness, or pain in your hands or feet

Trouble hearing; ringing or buzzing in your ears

Weakness all over

-

Motor

Trouble fastening buttons

Difficulty opening jars or feeling the shape of small objects in your hand

Trouble walking

MANAGING THE SYMPTOMS

The following suggestions may help you with symptoms of peripheral neuropathy. Always check with your healthcare provider before taking new medications.

Massage the affected area with cocoa butter.

Take B-complex vitamins.

Take folic acid supplements.

Take amino acid supplements.

If symptoms become more severe, your healthcare provider may recommend the following.

Pain medication or other medication for nerve pain relief

Stopping treatment for a period of time

Lowering the dose of treatment

Physical therapy

Taking care of peripheral neuropathy symptoms will allow you to move more easily and safely, carry out your daily activities, and prevent unnecessary pain and discomfort.

Note. For more information, please contact the International Myeloma Foundation (1-800-452-CURE; www.myeloma.org). The foundation offers the Myeloma Manager® Personal Care Assistant® computer program to help patients and healthcare providers keep track of information and treatments. Visit http://manager.myeloma.org to download the free software.

Note. Patient education sheets were developed in June 2008 based on the International Myeloma Foundation Nurse Leadership Board’s consensus guidelines. They may be reproduced for noncommercial use.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Brian G.M. Durie, MD, and Robert Kyle, MD, for critical review of the manuscript and Lynne Lederman, PhD, medical writer for the International Myeloma Foundation, for assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Joseph D. Tariman, Email: jtariman@u.washington.edu, Predoctoral fellow in the Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems Department in the School of Nursing at the University of Washington in Seattle. Member of the speakers bureau for Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Ginger Love, Clinical nurse coordinator at University Hematology Oncology in Cincinnati, OH. Member of the speakers bureaus for Celgene Corporation and Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Emily McCullagh, Autologous transplant coordinator at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, NY.

Stacey Sandifer, Staff RN at the Cancer Centers of the Carolinas in Greenville, SC.

References

- American Cancer Society. Pain management pocket tool. 2005 Retrieved September 10, 2007, from http://www.cancer.org/docroot/PRO/content/PRO_1_1_Pain_Management_Pocket_Tool.asp.

- Anderson K, Richardson P, Chanan-Khan A, Schlossman R, Munshi N, Oaklander A, et al. Single agent bortezomib in previously untreated multiple myeloma (MM): Results of a phase II multicenter study. 2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part 1 [Abstract] Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(18 Suppl):7504. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong T, Almadrones L, Gilbert MR. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32(2):305–311. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.305-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti P, Bilotti E, Colson K, Curran K, Doss D, Faiman B, et al. Nursing guidelines for enhanced patient care. Haematologica. 2007;92(Suppl 2):211. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti P, Bilotti E, Colson K, Curran K, Doss D, Faiman B, et al. Management of side effects of novel therapies for multiple myeloma: Consensus statements developed by the International Myeloma Foundation’s Nurse Leadership Board. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008;12(3 Suppl):9–12. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.S1.9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun EA, Fishman DA, Roland PY, Lurain JR, Chang CH, Cella D. Validity and selectivity of the FACT/GOG-Ntx [Abstract 1751] Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2000 Retrieved April 7, 2008, from http://www.asco.org/ASCO/Abstracts+%26+Virtual+Meeting/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=2&abstractID=202320.

- Cavaletti G, Boglium F, Marzorati L, Zincone A, Piatti M, Colombo N, et al. Grading of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity using the Total Neuropathy Scale. Neurology. 2003;61(9):1297–1300. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000092015.03923.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celgene Corporation. Revlimid® (lenalidomide) [Package insert] Summit, NJ: Author; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Celgene Corporation. Thalomid® (thalidomide) [Package insert] Summit, NJ: Author; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF. FACIT: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy. 1997 Retrieved September 24, 2007, from http://www.facit.org/qview/qlist.aspx.

- Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Serafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson K, Doss DS, Swift R, Tariman J, Thomas TE. Bortezomib, a newly approved proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma: Nursing implications. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2004;8(5):473–480. doi: 10.1188/04.CJON.473-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblath DB, Chaudhry V, Carter K, Lee D, Seysedadr M, Miernicki M, et al. Total Neuropathy Score. Validation and reliability study. Neurology. 1999;53(8):1660–1664. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.8.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA. Neurological aspects of multiple myeloma and related disorders. Best Practice and Research Clinical Haematology. 2005;18(4):673–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss DS. Advances in oral therapy in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2006;10(4):514–520. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.514-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Pharmaceuticals. Lidoderm® (lidocaine patch 5%) [Package insert] Chadds Ford, PA: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fahdi IE, Gaddam V, Saucedo JF, Kishan CV, Vyas K, Deneke MG, et al. Bradycardia during therapy for multiple myeloma with thalidomide. American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;93(8):1052–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghobrial J, Ghobrial IM, Mitsiades C, Leleu X, Hatjiharissi E, Moreau AS, et al. Novel therapeutic avenues in myeloma: Changing the treatment paradigm. Oncology. 2007;21(7):785–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonial S. Balancing efficacy and toxicity: Addressing peripheral neuropathy and enhancing quality of life. American Journal of Hematology/Oncology. 2007;6(4):194–196. [Google Scholar]

- Manochakian R, Miller KC, Chanan-Khan AA. Clinical impact of bortezomib in frontline regimens for patients with multiple myeloma. Oncologist. 2007;12(8):978–990. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-8-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs J, Newton S. Updating your peripheral neuropathy “know-how. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2003;7(3):299–303. doi: 10.1188/03.CJON.299-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileshkin L, Stark R, Day B, Seymour JF, Zeldis JB, Prince HM. Development of neuropathy in patients with myeloma treated with thalidomide: Patterns of occurrence and the role of electrophysiologic monitoring. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(27):4507–4514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Velcade® (bortezomib) [Package insert] Cambridge, MA: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v.3.0. 2006 Retrieved August 8, 2007, from http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™: Adult cancer pain [v.1.2007] 2007 Retrieved September 20, 2007, from http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/pain.pdf.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network & American Cancer Society. Cancer pain: Treatment guidelines for patients. 2005 Retrieved September 20, 2007, from http://www.nccn.org/patients/patient_gls/_english/pdf/NCCN%20Pain%20Guidelines.pdf.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Peripheral neuropathy fact sheet. 2007 Retrieved October 23, 2007, from http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/peripheralneuropathy/detail_peripheralneuropathy.htm.

- Oncology Nursing Society. Cancer pain management [Position statement] 2004 Retrieved November 17, 2006, from http://www.ons.org/publications/positions/documents/pdfs/CancerPain.pdf.

- Orlowski RZ, Stinchcombe TE, Mitchell BS, Shea TC, Baldwin AS, Stahl S, et al. Phase I trial of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(22):4420–4427. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.01.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plasmati R, Pastorelli F, Cabo M, Petracci E, Zamagni E, Tosi P, et al. Neuropathy in multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide: A prospective study. Neurology. 2007;69(6):573–581. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267271.18475.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar SV, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Geyer SM, Kabat B, et al. Combination therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (Rev/Dex) for newly diagnosed myeloma. Blood. 2005;106(13):4050–4053. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PG, Anderson K. Thalidomide and dexamethasone: A new standard of care for initial therapy in multiple myeloma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(3):334–335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, Jagannath S, Zeldenrust SR, Alsina M, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(10):3458–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PG, Briemberg H, Jagannath S, Wen PY, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. Frequency, characteristics, and reversibility of peripheral neuropathy during treatment of advanced multiple myeloma with bortezomib. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(19):3113–3120. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PG, Briemberg H, Jagannath S, Wen PY, Schlossman RL, Doss D, et al. Reversible peripheral neuropathy during treatment of multiple myeloma with bortezomib: A case history. American Journal of Hematology/Oncology. 2007;6(4):189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Anderson KC. The emerging role of novel therapies for the treatment of relapsed myeloma. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2007;5(2):149–162. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropper AH, Gorson KC. Neuropathies associated with paraproteinemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(22):1601–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805283382207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MH, Young D, Kindler HL, Webb I, Kleiber B, Wright J, et al. Phase II study of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (PS-341) in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(18 Pt 1):6111–6118. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal S, Mehta J. Thalidomide in cancer: Potential uses and limitations. BioDrugs. 2001;15(3):163–172. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200115030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney C. Understanding peripheral neuropathy in patients with cancer: Background and patient assessment. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2002;6(3):163–166. doi: 10.1188/02.CJON.163-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariman JD. Thalidomide: Current therapeutic uses and management of its toxicities. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2003;7(2):143–147. doi: 10.1188/03.CJON.143-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariman JD. Multiple myeloma. In: Yarbro CH, Frogge MH, Goodman M, editors. Cancer nursing: Principles and practice. 6. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2005. pp. 1460–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Tosi P, Zamagni E, Cellini C, Plasmati R, Cangini D, Tacchetti P, et al. Neurological toxicity of long-term (> 1 yr) thalidomide therapy in patients with multiple myeloma. European Journal of Haematology. 2005;74(3):212–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visovsky C, Collins ML, Hart C, Abbott LI, Aschenbrenner JA. Oncology Nursing Society Putting Evidence Into Practice®: Peripheral neuropathy. 2007 doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.901-913. Retrieved October 19, 2007, from http://www.ons.org/outcomes/volume2/peripheral/pdf/PEPCardDet_peripheral.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, Wang M, Belch A, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(21):2133–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham R. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A review and implications for oncology nursing practice. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2007;11(3):361–376. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.361-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]