Abstract

Objectives

A previous pilot trial evaluating computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT4CBT) among 77 heterogeneous substance users (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, opioids) provided preliminary support for its efficacy in the context of a community-based outpatient clinic. Aims of the present trial were to conduct a more definitive trial in a larger, more homogeneous sample.

Methods

Randomized clinical trial in which 101 cocaine-dependent methadone maintained individuals were randomized to standard methadone maintenance or methadone maintenance with weekly access to CBT4CBT, with 7 modules delivered within an 8 week trial.

Results

Treatment retention and data availability were high and comparable across the treatment conditions. Participants assigned to the CBT4CBT condition were significantly more likely to attain three or more consecutive weeks of abstinence from cocaine (36 versus 17%, p<.05, OR=.36). The group assigned to CBT4CBT also had better outcomes on most dimensions, including urine specimens negative for all drugs, but these reached statistical significance only for the completer sample (N=69). Follow-up data collected 6 months after treatment termination were available from 93% of the randomized sample; these indicated continued improvement for those assigned to the CBT4CBTgroup, replicating previous findings regarding its durability.

Conclusions

This trial replicates earlier findings indicating CBT4CBT is an effective adjunct to addiction treatment with durable effects. CBT4CBT is an easily disseminable strategy for broadening the availability of CBT, even in challenging populations such as cocaine-dependent individuals enrolled in methadone maintenance programs.

Clinical trials.gov ID number NCT00350610

Introduction

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has a comparatively strong level of empirical support across a range of psychiatric disorders (1), including substance use disorders (2, 3). Despite evidence of positive and durable outcomes (4, 5), CBT remains rarely implemented in the range of settings where individuals with substance use disorders are treated (6). There are a number of obstacles to delivering CBT and other empirically validated therapies in clinical practice, including the limited availability of professional and specialty training programs that provide high quality training, supervision and certification in CBT (7); high rates of clinician turnover and lack of a CBT-trained workforce in many treatment settings (8); the relative complexity and cost of training clinicians in CBT (9, 10); as well as high case loads and limited resources in many settings. Moreover, for the addictions and other psychiatric disorders, available evidence suggests only a minority of individuals who could benefit from treatment actually receive high quality evidence based treatment (11). Hence, computer-assisted delivery of CBT, if demonstrated to be feasible and effective, could play an important role in broadening its availability, reducing costs, improving the quality and greatly extending the reach of treatment (12, 13).

The potential of computer-assisted therapies has led to a burgeoning of new internet and computer-assisted approaches for a range of psychiatric disorders (14). There are now meta-analytic evaluations of computer/internet interventions for multiple disorders, including depression(15), anxiety (16), illicit drugs (17), smoking (18), and alcohol (19). While generally positive and reporting effect sizes in the moderate range, these analyses and systematic reviews uniformly stress the highly variable methodological quality of the trials, with the most common weaknesses being limited adherence, high dropout rates, lack of adequate follow-up, reliance on self-reported outcomes, and inadequate replication (20, 21).

A preliminary randomized evaluation of computer based training for CBT (CBT4CBT) as an adjunct to standard addiction treatment compared it to standard treatment alone among 77 individuals seeking outpatient treatment for a range of substance use disorders (22). Participants were predominantly alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, or opioid dependent, with use of multiple substances reported by most participants (80%). At the end of the 8-week trial, participants assigned to the CBT4CBT condition submitted significantly more urine specimens that were negative for any type of drugs and tended to have longer continuous periods of abstinence during treatment. A six-month follow-up of 82% of the intention to treat sample indicated significantly better durability of effects of CBT4CBT over standard treatment, for both self-report and urinalysis data (23). Limitations of this preliminary study included the small sample size and highly heterogeneous sample that varied greatly in both type and severity of substance use at baseline.

In this report, we describe primary outcome results from a larger, randomized clinical trial of CBT4CBT in a more homogeneous, but highly challenging, clinical population, that is, cocaine-dependent methadone-maintained individuals. Cocaine use is among the most prevalent and intractable problems within methadone maintenance programs (24, 25), and is associated with a wide range of problems including HIV, Hepatitis C (HCV), and multiple other morbidities (26). Methadone treatment programs in the US face rapidly growing censuses, patients presenting with more complex and severe problems, and fewer resources with which to treat them.

In the present trial, cocaine-dependent individuals stabilized on methadone were randomized to standard methadone maintenance (treatment as usual, TAU) or TAU plus CBT4CBT over a period of 8 weeks. Given the established efficacy of clinician-delivered CBT across a range of addictions (2, 3) and the very limited availability of empirically validated therapies in many community based settings, CBT4CBT was evaluated in terms of how it is most likely be used in these settings, that is, as a stand-alone addition to regular methadone services. The primary hypothesis was that individuals assigned to CBT4CBT would reduce their frequency of cocaine and other substance use and submit fewer positive urine toxicology screens than those randomized to TAU. We also hypothesized that the effects of CBT4CBT would be durable relative to TAU through a six-month follow-up. Finally, we compared the groups regarding effects of treatment on HIV risk behavior, as an HIV risk reduction component was added to CBT4CBT to address the high rate of drug- and sex-related risk behaviors in this population (27, 28).

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from individuals enrolled in one of the methadone maintenance programs of the APT Foundation, the largest provider of methadone maintenance services in New Haven, Connecticut. Participants were English-speaking adults, stabilized on methadone (same dose>2 months), who met DSM-IV criteria for current (within the past 30 days) cocaine dependence. As in our previous trial, exclusion criteria were minimized in order to facilitate recruitment of a broad and clinically representative group of individuals enrolled in this setting. Thus, individuals were excluded only if (1) they failed to meet DSM-IV criteria for current cocaine dependence, (2) had an untreated/unstabilized psychotic disorder or had current suicidal/homicidal ideation such that more intensive treatment was indicated, or (3) could not read at a 6th grade level (required for provision of written informed consent and completion of assessment instruments).

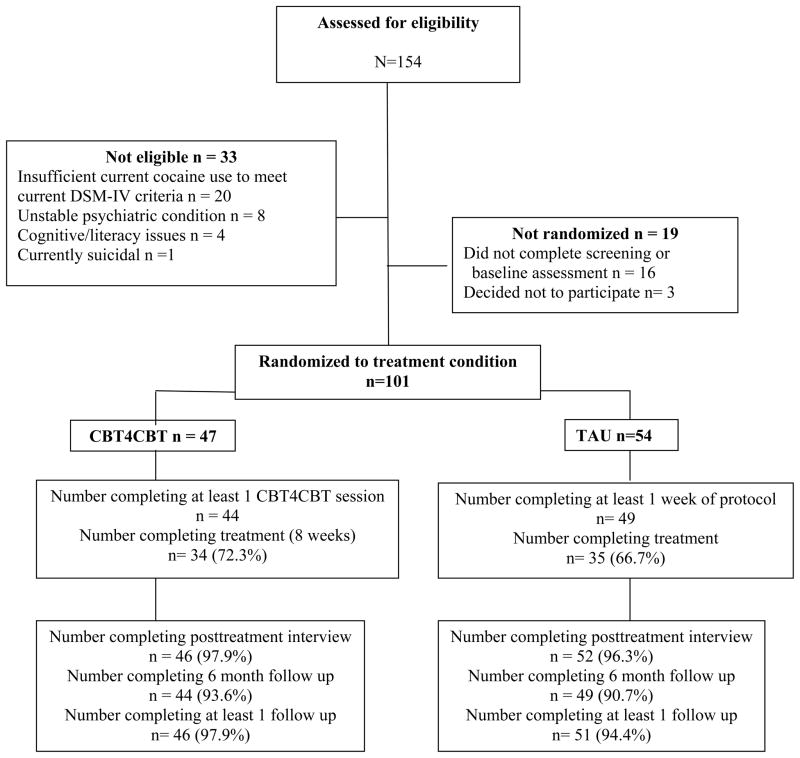

As shown in the CONSORT diagram (Figure 1), 101 of the 154 individuals screened were determined to be eligible for the study, provided written informed consent and were randomized. Following description of the study and provision of written informed consent approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigations Committee, participants were randomized to either TAU or CBT4CBT, using a computerized urn randomization program (29) to balance treatment groups with respect to gender, ethnicity, education level, and frequency of cocaine use at baseline.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram, flow of participants through study

Treatments

All participants were offered standard treatment at the clinic, which consisted of daily methadone maintenance and weekly group sessions. Participants also met twice weekly with an independent research assistant who collected urine specimens, assessed recent substance use and monitored other clinical symptoms. Those randomized to the CBT4CBT condition were provided access to the program on a dedicated computer in a private room within the clinic. The research assistant guided participants through their initial use of the CBT4CBT program and was available if needed to answer questions and assist participants each time they accessed the program. Participants accessed the program through an ID/password system to protect confidentiality.

As described earlier (22), the CBT4CBT program was user-friendly and required no previous experience with computers nor reading skills (any material presented in text was also read by an on-screen narrator) and collected no protected health information (PHI). The program was media-rich, using games, cartoons, quizzes and other interactive exercises to teach and model effective use of skills and strategies. At its core was a series of videos which, for each topic, present connected scenes of engaging characters, portrayed by professional actors. These characters first experience a common risky situation or problem and then, after the skill is presented as described above, demonstrate using the targeted skill to successfully negotiate that situation without resorting to drug use.

Assessments

Participants were assessed before treatment, twice weekly during treatment, at the 8-week treatment termination point, and 1, 3, and 6 months after the termination point by a research assistant. Participants were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (30) prior to randomization to establish substance use and other psychiatric diagnoses. The Substance Use Calendar, similar to the Timeline Follow Back (31), was administered weekly during treatment to collect day-by-day self-reports of drug and alcohol use for the 28-day period prior to randomization, as well as throughout the 56-day treatment phase and the 6-month follow-up. HIV risk behaviors were assessed using the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB) (32).

Participant self-reports of drug use were verified through urine toxicology screens that were obtained at every assessment visit. Of 875 urine specimens collected during the treatment phase of the study (between days 4 and 56), the majority (84.7%) were consistent with participant self-report; only 106 (12%) were positive for cocaine in cases where the participant had denied recent use during the 3 day period that cocaine metabolites are typically detectable in urine. Finally, given that a weakness of the computerized therapy literature is the lack of attention to potential adverse events associated with computerized therapies (20, 21), possible adverse events and hospitalizations were monitored and reviewed regularly by the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) using procedures worked out in previous multisite behavioral trials (33).

Data analyses

The primary outcome measures were change in self-reported drug use over time (days of cocaine use by week), results of urine toxicology screens (operationalized as the percentage of drug-negative urine samples collected during treatment) and attainment of three or more weeks of continuous abstinence, a variable found in multiple trials to be predictive of better long-term cocaine outcomes (34). Secondary outcomes included reductions in self-reported HIV risk behaviors. The principal data analytic strategy was random effects regression analysis for the longitudinal outcome (days of cocaine use by week during the 8 weeks of active treatment) and analysis of variance for the other primary outcome variables (percent of urine specimens negative for cocaine, as well as for all other drugs; self-reported abstinence) for the 101 participants who were randomized to treatment (intention to treat), the 93 participants who initiated treatment (treatment-exposed), and the 69 who completed treatment. Follow up data was evaluated using a single piecewise random effect regression model (35) to assess change from pretreatment through follow up including treatment phase and associated interactions as independent variables. Results were highly consistent across analysis subsamples.

Results

Sample description

Table 1 presents baseline demographic characteristics and substance use and psychiatric diagnoses of the 101 randomized participants. Of these, 60% were female, 30% identified themselves as African American, 60% as European-American, and 8% as Latin American. Most (88%) were single or divorced, 89% were unemployed, and 71% had completed high school. The majority (77%) received some public assistance and 17% were on probation or parole. Participants used cocaine an average of 15 days a month and had been using for approximately 11 years. They reported using marijuana for about 2.5 days per month, and alcohol less than 1 day per month. ANOVA and chi-square analyses indicated no significant differences by treatment condition on these and other baseline variables as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline variables by treatment assignment, N= 101

| Categorical variables | CBT4CBT1 n=47 |

TAU 2 n=54 |

F or X2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n or mean | % or SD | n or mean | % or SD | |||

| Number (percent) female | 28 | 59.6% | 33 61.1% | .025 | .87 | |

| Ethnicity, number (%) | ||||||

| European American | 28 | 59.6 | 33 | 61.1 | 2.57 | .63 |

| African-American | 16 | 34 | 14 | 25.9 | ||

| Latin American | 3 | 6.4 | 5 | 9.3 | ||

| Native American, other | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.9 | ||

| Number (%) completed high school | 31 | 66 | 41 | 75.9 | 1.22 | .27 |

| Number (%) never married/living alone | 41 | 87.2 | 48 | 88.9 | 0.07 | .80 |

| Number (%) unemployed | 43 | 91.5 | 47 | 87 | 0.51 | .47 |

| Number (%) on probation or parole | 7 | 14.9 | 10 | 18.5 | 0.24 | .63 |

| Number (%) major depression - Lifetime3 | 15 | 31,9 | 14 | 25.9 | 0.44 | .51 |

| Number (%) anxiety disorder -Lifetime | 16 | 34 | 16 | 29.6 | 0.23 | .63 |

| Number (%) current alcohol use disorder | 1 | 2.2 | 3 | 5.7 | 0.77 | .38 |

| Continuous variables | ||||||

| Age, years | 42.7 | 9.5 | 41.3 | 9.7 | 0.55 | .46 |

| Years of regular cocaine use | 12.6 | 7.1 | 10.6 | 9.6 | 1.34 | .25 |

| Days of cocaine use, past 28 | 15.5 | 9.5 | 13.9 | 9.3 | 0.79 | .38 |

| Days of heroin use, past 28 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 5.2 | 0.77 | .38 |

| Days of marijuana use, past 28 | 1.8 | 5.3 | 3.1 | 7.2 | 1.06 | .31 |

| Days of alcohol use, past 28 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.60 | .44 |

| Age of first use of cocaine | 20.0 | 5.3 | 20.1 | 5.1 | 0.00 | .99 |

| ASI Medical Composite4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.13 | .72 |

| ASI Employment Composite | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.46 | .50 |

| ASI Alcohol Composite | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.89 | .35 |

| ASI Cocaine Composite | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.37 | .55 |

| ASI Other Drug Composite | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.04 | .31 |

| ASI Legal Composite | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.83 | .36 |

| ASI Family Composite | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.59 | .45 |

| ASI Psychological Composite | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.19 | .28 |

| Days paid for working, past 28 | 3.4 | 6.7 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 0.38 | .54 |

| Lifetime number of arrests | 11.7 | 14.0 | 11.0 | 14.4 | 0.06 | .82 |

| Number of prior outpatient treatment episodes | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 6.2 | 0.36 | .55 |

| Number of prior inpatient treatment episodes | 4.2 | 6.4 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 1.04 | .31 |

| Methadone dose at baseline, mg | 84.02 | 28.32 | 83.4 | 27.4 | 0.01 | .91 |

Note.

CBT4CBT indicates access to computer program in addition to standard methadone maintenance and counseling.

TAU indicates Standard methadone maintenance and counseling.

Indicates DSM-IV diagnosis from SCID interviews.

Indicates ASI composite score. Scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater severity of problems. All statistical tests are two-tailed.

Treatment implementation, retention and data availability by condition

Of the 93 individuals who initiated the protocol, 69 (74%) completed the 8-week treatment protocol (34 in CBT4CBT, 35 in TAU, NS). Post-treatment data was collected from 98 individuals (97% of the intention-to-treat sample). Regarding rates of follow-up, 96% of the intention to treat sample was reached for at least one follow-up, and 92% were reached for the 6-month follow-up, as the vast majority (97%) were still enrolled in the methadone program. Hence, analyses of the primary substance use outcomes were not constrained by differential rates of attrition nor data availability. Regarding adverse events, there were no participant deaths during the trial and rates of serious adverse events (typically overnight hospitalizations) did not differ by treatment condition either within treatment or during follow-up (see Table 2). None were determined to be protocol-related by the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB).

Table 2.

Treatment process variables and serious adverse events (SAEs) by treatment assignment

| Variable | CBT4CBT N=47 |

TAU N=54 |

F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N or Mean | Sd or % | N or mean | Sd or % | |||

| Days In treatment (maximum =56) | 46.7 | 17.2 | 43.9 | 19.9 | 0.58 | .45 |

| Urine specimens provided | 9.5 | 5.0 | 10.8 | 2.8 | 1.81 | .18 |

| Total individual sessions within treatment | 3.7 | 1.8 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 0.8 | .38 |

| Total group sessions within treatment | 6.3 | 8.6 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 0.3 | .56 |

| Number (%) of participants with 1 or more SAEs1 within treatment | 3 | 6.4 | 1 | 1.9 | 1.4 | .24 |

| Number (%) of participants with 1 or more SAEs during follow-up | 8 | 17 | 6 | 11.1 | 0.8 | .39 |

Note. SAEs included medical hospitalizations (asthma, heart conditions) or brief inpatient substance use detoxification or stabilization.

As shown in Table 2, levels of exposure to the standard counseling services offered in the program were also comparable in both groups, with those assigned to CBT4CBT completing a mean of 47 days and those assigned to TAU completing 44 days of the 56 day protocol. Of those who initiated the CBT4CBT program, the mean number of computer sessions completed was 5.1 (SD=2.3) of the 7 modules offered (73%). Participants spent an average of 35.0 (SD= 8.6) minutes per session working with each module and tended to complete the modules in the order presented (e.g., 44/44 participants completed Module 1 (patterns of use and functional analysis), 38 completed Module 2 (coping with craving), 34 completed Module 3 (refusing offers), 31 completed Module 4 (problem solving), 26 completed Module 5 (addressing cognitions), 28 completed Module 6 (decision making), and 23 completed the HIV risk reduction module. Most (84.1%) completed at least one of the 6 weekly homework assignments, and participants completed an average of 2.9 homework assignments (maximum=6; SD=2.2).

Effects of treatment on cocaine and other drug use: Within treatment and 6-month follow up

Within-treatment cocaine use outcomes were consistently better among the group assigned to CBT4CBT compared with those assigned to TAU alone. As shown in Table 3, for the intention to treat sample, significantly more individuals assigned to CBT4CBT attained three or more continuous weeks of abstinence from cocaine within treatment (36 versus 17%). They also submitted more urine specimens free from all drugs (23 versus 12%), as well as cocaine (24 versus 19%), but these differences fell short of statistical significance. The urine-based outcomes indicators that were not significant for the intention to treat sample did attain statistical significance for the completer sample, including percent of urine specimens testing negative for cocaine as well as all other illicit drugs, but should be interpreted cautiously. Self-reported percent days of abstinence from cocaine did not differ significantly across treatment conditions.

Table 3.

Primary outcomes: Cocaine and other drug use within treatment: Randomized sample by treatment assignment

| Variable | CBT4CBT | TAU | F or X2 | p | Effect size 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N or mean | % or Sd | n or mean | % or Sd | ||||

| Randomized sample (N=101) | N=47 | N=54 | |||||

| Percent days of abstinence, self-report | 65.3 | 29.4 | 56.6 | 31.6 | 1.97 | .16 | .28 |

| Percent cocaine-free urine samples | 24.4 | 35.5 | 19.0 | 28.7 | 2.36 | .13 | .19 |

| Percent drug-free urine samples | 22.5 | 30.3 | 11.9 | 24.0 | 3.45 | .06 | .44 |

| Number and percent of sample attaining 3 or more weeks of continuous abstinence | 17 | 36.2 | 9 | 17.0 | 4.77 | .03 | .36 |

| Completer sample N=69 | N=34 | N=35 | |||||

| Percent days of abstinence, self-report | 67.8 | 26.4 | 59.4 | 27.7 | 1.65 | .23 | .30 |

| Percent cocaine-free urine samples | 33.3 | 34,2 | 18.8 | 24.4 | 4.14 | .05 | .59 |

| Percent drug-free urine samples | 26.7 | 29.8 | 12.4 | 21.9 | 5.16 | .03 | .65 |

| Number and proportion of sample attaining 3 or more weeks of continuous abstinence | 11 | 32.4 | 3 | 8.0 | 6.03 | .01 | .20 |

Note.

Indicates effect size expressed as Cohen’s d for means and odds ratio for proportions (Proportion of sample attaining 3 or more weeks of abstinence)

Longitudinal outcomes, that is, change in frequency of cocaine use by time, which paralleled those of the ‘static’ summary outcomes (percent negative urines, percent days abstinent), are presented in Figure 2. Random effects regression analyses indicated a significant effect for time, indicating reduction of frequency of cocaine use over the course of treatment for the sample as a whole (F (df 1, 792.6)=42.5, p<.001) as well as significant treatment group by time effect (F (df 1,792)=10.8, p=.002), indicating greater reduction in cocaine use by time for the participants assigned to CBT4CBT compared to TAU.

Figure 2.

Frequency of cocaine use by month, within treatment (months 0–2) and follow-up (months 3–8), estimates From random regression analyses by treatment assignment

The follow-up outcomes indicated relative durability of the effects of CBT4CBT through the 6 month follow up; these are also illustrated in Figure 2. These piecewise random effect regression analyses indicate a significant overall reduction in frequency of cocaine use by month from baseline assessment through the 6 month follow up (log F=35.92, p <.001), where, as expected, the rate of change within treatment was greater than the rate of change during follow up (effect of phase F = 4.41, p = .04). Overall, participants assigned to the CBT4CBT condition had a greater reduction in cocaine use compared to those assigned to TAU (group by log time 8.49, p < .001).

Effects on HIV Risk behavior

To evaluate possible effects of the addition of the HIV/STD risk reduction module, self-reported levels of risk were evaluated with the Risk Assessment Battery (32). Although overall risk levels were low, and analysis of group by time effects did not attain statistical significance, there was a marked decrease in self-reported drug risk behavior for those assigned to CBT4CBT relative to TAU. This effect did not persist during follow-up, however. Sex risk behaviors did not change appreciably in either condition.

Discussion

This randomized clinical trial of CBT4CBT as an adjunct to methadone maintenance therapy for 101 cocaine-dependent individuals indicated improved cocaine and drug use outcomes relative to standard methadone maintenance treatment (TAU). Those assigned to CBT4CBT were significantly more likely to attain 3 or more consecutive weeks of abstinence within treatment, an outcome indicator associated with better long-term cocaine use outcomes and general functioning across multiple trials. Results of a 6-month follow-up also indicated significant enduring benefit of CBT4CBT relative to TAU over time. Effects on percent of urine specimens negative for all illicit drugs also approached statistical significance.

To our knowledge, this represents the first replication, via randomized clinical trial, of a computer-assisted therapy for addiction (20). This is significant because replication studies, while critical to the advancement of science (36), are comparatively rare in the clinical science literature (37) Moreover, evidence standards for both pharmacologic and behavioral therapies require replication before a therapy can be considered evidence-based (38). Furthermore, we found these favorable outcomes for CBT4CBT when used with a particularly highly challenging population, methadone-maintained cocaine-dependent individuals, many of whom used other drugs in addition to cocaine. Other than Contingency Management, there have been few behavioral or pharmacologic treatments to find a positive effect, much less a durable one, in this population (39). Finally, while the overall magnitude of reduction of drug use in this sample was modest, results do compare favorably with those of recent randomized trials in this population (39–41); and effect sizes were comparable with those found in the initial trial of CBT4CBT (range .45–59).

The durability of effects of CBT4CBT reported for the initial trial (23), and consistent with clinician-delivered CBT (4), was also replicated here. Few if any other behavioral therapies, and no pharmacologic therapies for cocaine dependence, have demonstrated durable effects once terminated. As addictions are a chronic relapsing condition, durability of effects is a particularly important feature of any empirically validated therapy (42).

The effect of the HIV risk reduction module on risk behavior in this sample was more mixed. As it was the last module delivered, only half of those assigned to CBT4CBT completed it (22/44). Level of self-reported drug-related risk behaviors as assessed by the RAB fell to 0 in the CBT4CBT group by the end of treatment, but analyses did not indicate statistically significant differences by treatment condition. An ongoing trial is evaluating the efficacy of this module, delivered alone, on frequency of high risk behaviors in comparison to standard HIV risk reduction groups in the context of a methadone maintenance program.

Strengths of this protocol included methodological features of importance for rigorous clinical trials of computer-assisted therapies (20, 21) and therapist-delivered behavioral therapies more broadly (38). These include randomization to treatment, follow-up at 6 months of 92% of the sample, assessment of primary outcome using both urine toxicology screen and validated self-report instruments, adequate sample size with intention to treat analyses of outcomes using appropriate statistical procedures, monitoring and reporting of adverse events, and requiring all participants to meet standardized diagnostic criteria for cocaine and opioid dependence. Moreover, in contrast to many computer-delivered interventions where low levels of adherence typically limit inferences that can be drawn regarding effectiveness (18, 20, 43), level of engagement with the CBT4CBT program was comparatively high, as participants completed an average of 73% of sessions offered.

This study had several limitations as well. First, CBT4CBT was evaluated as an add-on to treatment, and thus conditions were not balanced for time spent and attention. Further, it cannot yet be concluded that effects of CBT4CBT are comparable with those of individual clinician-delivered CBT. For the intention to treat sample, results of study treatments on rates on overall rates of cocaine and all-drug negative urine specimens approached, but did not reach statistical significance. However, rates of negative urine screens did reach statistical significance in the sample of treatment completers, highlighting the importance of retention in evaluation treatment outcomes. Moreover, these effects were seen in the context of participants also attending group and individual counseling at least once per week while the trial was ongoing.

Overall, this extension of an initial trial of CBT4CBT to a more homogeneous (in terms of all participants meeting criteria for current cocaine dependence in addition to opioid dependence) but highly challenging clinical population is another milestone in the validation of this cost-effective (44), easily disseminable approach. A major strength of the CBT4CBT approach itself is the ease of implementation, dissemination, and sustainability of the computer-assisted therapy. Given the multiple roadblocks to implementation of empirically supported therapies into practice, this study confirms that CBT4CBT may provide a safe, inexpensive, and sustainable option for doing so.

Next steps for this line of research include less tightly controlled effectiveness trials which address feasibility and clinical outcomes when delivered in clinical settings. Another line of research would involve evaluation of the efficacy of CBT4CBT with limited clinician involvement (that is, as a stand-alone approach rather than as a clinician extender); as well as direct comparisons of computer-delivered CBT4CBT with CBT when delivered by well trained and closely supervised clinicians, all of which are ongoing in our clinics. In addition, we are exploring the utility of the program when adapted for use by other clinical populations (alcohol-dependent, Spanish-speaking). Ultimately, we hope that carefully studied approaches like CBT4CBT may provide a new paradigm for treating a wide variety of addictive disorders in a broad range of settings.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R37-DA 015969 and P50-DA09241. We gratefully acknowledge the support of Amanda Schackell, Martha Wright, and Kim DiMeola of the APT Foundation and particularly the individuals who participated in this trial. Karen Hunkele, Liz Vollono, and Joanne Corvino provided critical support in implementing the trial and data analysis. We are deeply grateful for the creativity, skill, and resourcefulness of Rick Leone, Craig Tomlin, and Doug Forbush of Yale ITS MedMedia.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Carroll is a consultant to CBT4CBT LLC, which makes CBT4CBT available to qualified clinical providers and organizations on a commercial basis. Dr. Carroll works with Yale University to manage any potential conflicts of interest.

Literature cited

- 1.Roth A, Fonagy P. What Works for Whom? A Critical Review of the Psychotherapy Literature. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magill M, Ray LA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stud Alc Drugs. 2009;70:516–527. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, Gawin F. One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence. Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolin DF. Is cognitive-behavioral therapy more effective than other therapies? A meta-analytic review. Clin Psych Rev. 2010;30:710–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-Based Drug and Alcohol Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SE, Betts K, Mufson L, Fitterling H, Wickramaratne P. National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:925–934. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLellan AT, Meyers K. Contemporary addiction treatment. a review of systems problems for adults and adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sholomskas D, Syracuse G, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies for training clinicians in cognitive behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Carroll KM. Manual-guided cognitive behavioral therapy training: A promising method for disseminating empirically supported substance abuse treatments to the practice community. Psych Addict Behav. 2001;15:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance Use Conditions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Computer-assisted therapy in psychiatry: Be brave-it’s a new world. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:426–432. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greist JH. A promising debut for computerized therapies. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:793–795. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks IM, Cavanagh K, Gega L. Hands On Help: Computer-Aided Psychotherapy. Hove, UK: Psychol. Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V. Internet-based cognitive-behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:319–328. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tait RJ, Spijkerman R, Riper H. Internet and computer based interventions for cannabis use: A meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rooke S, Thorsteinsson E, Karpin A, Copeland J, Allsop D. Computer-delivered interventions for alcohol and tobacco use: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2010;105:1381–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Hewitt C, Hartley S, Godfrey C. Can stand-alone computer-based interventions reduce alcohol consumption? A systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:267–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiluk BD, Sugarman DE, Nich C, Gibbons CJ, Martino S, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. A methodological analysis of randomized clinical trials of computer-assisted therapies for psychiatric disorders: toward improved standards for an emerging field. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:790–799. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.So M, Yamaguchi S, Hashimoto S, Sado M, Furukawa TS, McCrone P. Is computerised CBT really helpful for adult depression? A meta-analytic reevaluation of CCBT for adult depression in terms of clinical implementation and methodological validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2013:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio T, Gordon MA, Portnoy GA, Rounsaville BJ. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction. A randomized clinical trial of ‘CBT4CBT’. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:881–888. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, Rounsaville BJ. Enduring effects of a computer-assisted training program for cognitive-behavioral therapy: A six-month follow-up of CBT4CBT. Drug Alco Depend. 2009;100:178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shottenfeld RS. Methadone maintenance treatment. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD, editors. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008. pp. 289–208. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowinson JH, Marion I, Joseph H, Langrod J, Salsitz EA, Payte JT, Dole VP. Methadone maintenance. In: Lowinson J, Ruiz P, Millman RB, Langrod JG, editors. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 4. 2005. pp. 616–633. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ball JC, Ross A. The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLellan AT, Arndt IO, Metzger D, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. JAMA. 1993;269:1953–1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margolin A, Avants SK, Warburton LA, Hawkins KA, Shi J. A randomized clinical trial of a manual-guided risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive injection drug users. Health Psychol. 2003;22:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, DelBoca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;(Suppl 12):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Patient Edition. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navaline HA, Snider EC, Petro CJ, Tobin D, Metzger D, Alterman AI, Woody GE. An automated version of the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB): Enhancing the assessment of risk behaviors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10 (supplement 2):281–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petry NM, Roll JM, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Stitzer M, Peirce JM, Blaine J, Kirby KC, McCarty D, Carroll KM. Serious adverse events in randomized psychosocial treatment studies: safety or arbitrary edicts? J Consul Clin Psychol. 2008;76:1076–1082. doi: 10.1037/a0013679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins ST, Wong CJ, Badger GJ, Haug-Ogden DE, Dantona RL. Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and one year follow-up. J Consult Clinl Psychol. 2000;68:64–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applying Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jasny BR, Chin G, Chong L, Vignieri S. Again, and again, and again.....: Introduction to the Special Section on Data Replication and Reproducibility. Science. 2011:334. doi: 10.1126/science.334.6060.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makel M, Plucker JA, Hegarty B. Replications in psychology research: How often do they really occur? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012:7. doi: 10.1177/1745691612460688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peirce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine JD, Kellog S, Satterfield F, Schwartz M, Krasnansky J, Pencer E, Silva-Vazquez L, Kirby KC, Royer-Malvestuto C, Roll JM, Cohen A, Copersino ML, Kolodner K, Li R for the Clinical Trials Network. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: A National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Arch Genl Psychiatry. 2006;63:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poling J, Oliveto A, Petry NM, Sofuoflu M, Gonsai K, Gonzalez G, Martell B, Kosten TR. Six-month trial of bupropion with contingency management for cocaine dependence in a methadone-maintained population. Arch Genl Psychiatry. 2006;63:219–228. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petry NM, Martin B. Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine- and opioid-abusing methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:398–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuijpers P, Marks IM, Van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, Andersson G. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Cog Behav Ther. 2009;38:66–82. doi: 10.1080/16506070802694776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olmstead TA, Ostrow CD, Carroll KM. Cost-effectiveness of computer-assisted training in cognitive-behavioral therapy as an adjunct to standard care for addiction. Drug Alc Depend. 2010;110:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]