Abstract

careHPV, a lower-cost DNA test for human papillomavirus (HPV), is being considered for cervical cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries. However, not a single large-scaled study exists to investigate the optimal positive cutoff point of careHPV test. We pooled data for 9,785 women participating in two individual studies conducted from 2007 to 2011 in rural China. Woman underwent multiple screening tests, including careHPV on clinician-collected specimens (careHPV-C) and self-collected specimens (careHPV-S), and Hybrid Capture 2 on clinician-collected specimens (HC2-C) as a reference standard. The primary endpoint was cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe (CIN3+) (n = 127), and secondary endpoint was CIN2+ (n = 213). The area under the curves (AUCs) for HC2-C and careHPV-C were similar (0.954 versus 0.948, P = 0.166), and better than careHPV-S (0.878; P < 0.001 versus both). The optimal positive cutoff points for HC2-C, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S were 1.40, 1.74, and 0.85, respectively. At the same cutoff point, careHPV-C was not significantly less sensitive and more specific for CIN3+ than HC2-C, and careHPV-S was significantly less sensitive for CIN3+ than careHPV-C and HC2-C. Raising the cutoff point of careHPV-C from 1.0 to 2.0 could result in nonsignificantly lower sensitivity but significantly higher specificity. Similar results were observed using CIN2+ endpoint. careHPV using either clinician- or self-collected specimens performed well in detecting cervical precancer and cancer. We found that the optimal cutoff points of careHPV were 2.0 on clinician-collected specimens and 1.0 on self-collected specimens.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence and mortality of cervical cancer have decreased significantly in industrialized nations by establishing well-organized, cytology-based cervical cancer screening with timely follow-up of screen positives and treatment of precursor lesions (1). Such programs have been difficult to establish in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to well-documented issues: lack of the necessary infrastructure and quality control systems, only moderate sensitivity for precancerous lesions, and poor reliability (2, 3). The discovery that persistent cervical infections by approximately 13 high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) types cause virtually all cervical cancer and its immediate precursors everywhere in the world has led to the development of molecular tests for HPV detection. Clinical trials have demonstrated that HPV testing reduces the incidence of cervical cancer within 4 to 5 years (4, 5) and mortality due to cervical cancer within 8 years (6) compared to Pap testing.

There are several U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved HPV tests with high sensitivity for cervical precancer and cancer. However, for LMICs, simpler, more portable, and lower-cost HPV tests might be desirable to increase access to cervical cancer screening, especially in rural areas that may not have access to, or the logistics for, centralized testing.

Fortunately, a new test for HPV DNA (careHPV; Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD) has been developed that detects a pool of 14 HPV types in approximately 3 h at a cost of about $5 per test. Specialized training and education are not required to run the test. It has been evaluated in multiple countries and found that careHPV is a sensitive and reasonably specific screening test for cervical precancer and cancer (7–12). In 2012, the China Food and Drug Administration approved this test for cervical cancer screening (13).

The threshold of careHPV, recommended by the manufacturer, is the same as the one for Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2; Qiagen), the FDA-approved HPV test on which careHPV was based, at the relative light units/cutoff ratio (RLU/CO) of 1.0. Nevertheless, studies pointed out that raising the positive cutoff point of HC2 could achieve a better balance between the clinical sensitivity and specificity (14–16). HC2 and careHPV can test either clinician- or self-collected specimens.

One of the important advantages of using hrHPV testing for primary screening is the possibility of utilizing self-collected specimens. Although the use of self-collected specimens decreases the sensitivity for cervical precancer and cancer compared to clinically collected specimens (17, 18), its sensitivity is superior to that of visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and conventional cytology in detecting cervical precancer and cancer (17, 19). Furthermore, self-sampling does not require a clinic visit for specimen collection and thus might be used to increase population coverage (17, 20).

To examine the issue of the optimal cutoff points for careHPV testing on clinician- and self-collected specimens, we pooled data from almost 10,000 women participating in two early, population-based studies of careHPV conducted in rural China. Because women were screened with multiple tests, including careHPV testing on clinician- and self-collected specimens, and all screen-positive women underwent colposcopy and multiple biopsies, virtually all women with cervical precancer and cancer were referred to colposcopy, permitting the conduct of rigorous retrospective receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and optimal positive cutoff points determination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

In 2007, 2,530 women aged 30 to 54 years living in Wuxiang and Xiangyuan counties were enrolled in the Screening Technologies to Advance Rapid Testing (START) project (8). In 2010 and 2011, 7,541 women aged 25 to 65 years living in Yangcheng, Xinmi, and Tonggu counties were enrolled in the Screening Technologies to Advance Rapid Testing—Utility and Program (START-UP) project (9). Women who were sexually active, not pregnant, had an intact uterus and had no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), cervical cancer, or pelvic radiation were eligible for these two projects and the present study. Details on participants recruitment have been published elsewhere (8, 9).

The human subjects review boards of the Cancer Institute/Hosptial, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CICAMS) and the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH) approved the studies. All participants provided written informed consent before entry into the studies.

Study procedures.

The study procedures are described in detail elsewhere (8, 9). Briefly, for the START project, participants provided one self-collected specimen for careHPV testing (careHPV-S) and two clinician-collected specimens, one for careHPV testing (careHPV-C) and the other for liquid-based cytology (LBC) and HC2 testing. After that, VIA and colposcopy were performed with directed biopsies. Women who tested positive for any of HC2, LBC, careHPV-S, and careHPV-C tests underwent a second colposcopy with four-quadrant cervical biopsies and endocervical curettage (ECC) (8). For the START-UP project, participants provided one self-collected specimen for careHPV (careHPV-S) and HC2 testing (HC2-S) and two clinician-collected specimens, one for OncoE6 testing (Arbor Vita Corp., Fremont, CA), which detects the E6 oncoprotein of HPV16, -18, and/or -45, and one for careHPV (careHPV-C) and HC2 testing (HC2-C). After specimen collection, women also underwent VIA. Women who tested positive for any of the six screening tests performed (VIA, OncoE6, HC2-C, HC2-S, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S) were referred to colposcopy, and an approximately 10% random sample of the women who tested negative for all screening tests (screen-negative women) underwent a rigorous colposcopic evaluation that included using a biopsy protocol as previously described (21). In both studies, women were instructed in the method of self-sampling using a conical-shaped brush (Qiagen) (i.e., insert the brush into the vagina until a resistance was met and then rotate the device three times before withdrawal).

HPV DNA testing.

HC2 and careHPV are signal amplification assays that combine antibody capture of HPV DNA and RNA probe hybrids and chemiluminescent signal detection which provide the RLU/CO as the semiquantitative measurement of viral load. The cutoff point of 1.0 RLU/CO (approximately equal to 1.0 pg of DNA/ml) was used for colposcopy referrals in both tests.

Pathology.

The CIN system was used for histology diagnosis. Pathologists in two projects were blinded to the clinical and laboratory information. In START, two pathologists from CICAMS independently reviewed every specimen with a third pathologist adjudicated between the discrepant diagnoses. All abnormal (CIN1 or worse) specimens and 10% randomly selected specimens of negatives were assessed by an external pathologist in Canada without knowledge of the Chinese diagnoses. The discordant diagnoses were reviewed by the Chinese and Canadian pathologists with sufficient discussions until a consensus diagnosis was reached. The worst of the histology findings, including directed, four-quadrant biopsies and ECC with concordant diagnoses, were used as the final diagnosis. Similarly, in START-UP project, primary diagnoses were provided by two CICAMS pathologists after reaching an agreement. A U.S. pathologist independently reviewed each initial biopsy or surgical specimen diagnosed as CIN2+, and any discordant diagnoses were settled from discussions with the Chinese pathologists. The final diagnosis was based on the worst of the concordant diagnosis of the directed, four-quadrant biopsies, ECC, and surgical specimens. The originally discordant rates for the two projects were 40.5% (15/37) and 46.7% (21/45) for CIN2 20.8% (19/24) and 23.3% (20/86) for CIN3, respectively.

Screening-negative women with no biopsy specimen taken or women with negative histology findings were classified as being negative for cervical neoplasia.

Statistical analysis.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe (CIN3+) and CIN2+ were used as the primary and secondary endpoints, respectively, to assess the accuracy of HC2-C, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S. When CIN3+ was used, all women with less than CIN3 diagnosis (including negative, CIN1, and CIN2) were deemed as histological negatives. The sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values (PPV), negative predictive values (NPV), positive likelihood ratios (PLR), and negative likelihood ratios (NLR) were calculated for cutoff points of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 10.0 RLU/CO. ROC analyses were used to describe the tests' accuracies by calculating the area under the curves (AUCs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), and the optimal positive cutoff points were initiated. The stratified analyses were done independently by median age (25 to 44 and 45 to 65). Nonparametric test was used to compare the differences of AUCs, and McNemar test was used to compare the differences between sensitivities and specificities at different cutoff points. SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and STATA 11.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) were used to analyze the data. Statistical significance was assessed by two-tailed tests at α level of 0.05. When three or more groups were compared, a Bonferroni-adjusted α was used to correct for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

A total of 10,071 women were screened, and 286 (2.8%) of them were excluded because of incomplete data (i.e., 119 were HPV positive, and 167 other tests were invalid or positive without a final diagnosis). Thus, 9,785 (97.2%) women were included in our analysis. The mean, median, and range of women's ages were 44.3 years (standard deviation = 8.3), 44 years, and 25 to 65 years, respectively. There were 248 (2.5%) CIN1, 86 (0.9%) CIN2, 116 (1.2%) CIN3, and 11 (0.1%) cancers diagnosed.

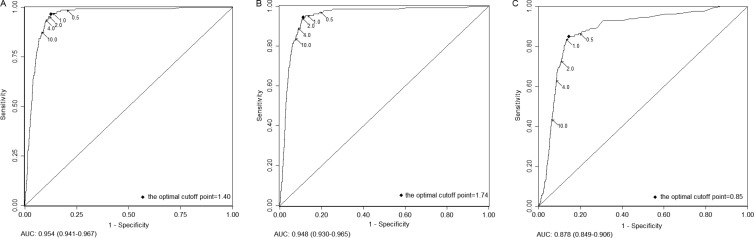

As is shown in Fig. 1, the performances of all three tests in detection of CIN3+ were good to excellent. The AUC was 0.954 (95% CI = 0.941 to 0.967), 0.948 (95% CI = 0.930 to 0.965), and 0.878 (95% CI = 0.849 to 0.906) for HC2-C, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S, respectively. There was no difference between the AUCs for HC2-C and careHPV-C (P = 0.166); the AUC for careHPV-S was less than those for HC2-C and careHPV-C (P < 0.001 for both). The optimal positive cutoff points were 1.40, 1.74, and 0.85 for HC2-C, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S, respectively, and the corresponding sensitivity and specificity were 96.85 and 87.39% for HC2-C, 94.49 and 88.76% for careHPV-C, and 85.04 and 85.74% for careHPV-S, respectively.

FIG 1.

ROC curves of HC2 on clinician-collected specimens and of careHPV on clinician-collected and self-collected specimens to detect CIN3+. (A) ROC curve of HC2 on clinician-collected specimens. (B) ROC curve of careHPV on clinician-collected specimens. (C) ROC curve of careHPV on self-collected specimens. The curves show the various combinations of cutoff points of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 10.0 directed by arrows. The solid diamond shows the optimal cutoff point on each curve. The ranges in parentheses are the 95% CIs of the AUC. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; CIN3+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe; AUC, area under the curve.

Table 1 shows the performance for HC2-C, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S at specific cutoff points in the range of 0.5 to 10.0, as well as for the optimal cutoff point for each test to detect CIN3+. The increase of the positive cutoff point from 0.5 to 10.0 decreased the sensitivity by ca. 10%, while increased the specificity by ca. 10% for HC2-C and careHPV-C. However, changing the positive cutoff point for careHPV-S had a large impact on sensitivity for detecting CIN3+ (i.e., the sensitivity decreased from 86.61 to 43.31%), while the specificity increased from 80.10 to 93.68%. To achieve similar sensitivity and NPV as HC2-C at 1.0 RLU/CO, the careHPV-C cutoff point should be set at 0.5, with a relative specificity, PPV, and PLR of 0.94, 0.74, and 0.72, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio of Hybrid Capture 2 on clinician-collected specimens and of careHPV on clinician-collected and self-collected specimens at a series of cutoff points to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe diagnosesa

| Test and cutoff point | No. of HPV-positive specimens (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | PLR | NLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC2-C | |||||||

| 0.50 | 2,085 (21.3) | 98.43 | 79.71 | 6.00 | 99.97 | 4.85 | 0.020 |

| 1.00 | 1,457 (14.9) | 96.85 | 86.19 | 8.44 | 99.95 | 7.01 | 0.037 |

| 1.40 | 1,341 (13.7) | 96.85 | 87.39 | 9.17 | 99.95 | 7.68 | 0.036 |

| 2.00 | 1,257 (12.8) | 95.28 | 88.24 | 9.63 | 99.93 | 8.10 | 0.054 |

| 4.00 | 1,113 (11.4) | 93.70 | 89.71 | 10.69 | 99.91 | 9.10 | 0.070 |

| 10.00 | 942 (9.6) | 87.40 | 91.40 | 11.78 | 99.82 | 10.16 | 0.138 |

| careHPV-C | |||||||

| 0.50 | 1,982 (20.3) | 96.85 | 80.75 | 6.21 | 99.95 | 5.03 | 0.039 |

| 1.00 | 1,401 (14.3) | 95.28 | 86.75 | 8.64 | 99.93 | 7.19 | 0.054 |

| 1.74 | 1,206 (12.3) | 94.49 | 88.76 | 9.95 | 99.92 | 8.40 | 0.062 |

| 2.00 | 1,165 (11.9) | 93.70 | 89.17 | 10.21 | 99.91 | 8.65 | 0.071 |

| 4.00 | 999 (10.2) | 88.98 | 90.83 | 11.31 | 99.84 | 9.70 | 0.121 |

| 10.00 | 820 (8.4) | 83.46 | 92.61 | 12.93 | 99.77 | 11.29 | 0.179 |

| careHPV-S | |||||||

| 0.50 | 2,032 (20.8) | 86.61 | 80.10 | 5.41 | 99.78 | 4.35 | 0.167 |

| 0.85 | 1,485 (15.2) | 85.04 | 85.74 | 7.27 | 99.77 | 5.96 | 0.175 |

| 1.00 | 1,398 (14.3) | 83.46 | 86.62 | 7.58 | 99.75 | 6.24 | 0.191 |

| 2.00 | 1,121 (11.5) | 72.44 | 89.35 | 8.21 | 99.60 | 6.80 | 0.309 |

| 4.00 | 900 (9.2) | 62.99 | 91.51 | 8.89 | 99.47 | 7.42 | 0.404 |

| 10.00 | 665 (6.8) | 43.31 | 93.68 | 8.27 | 99.21 | 6.86 | 0.605 |

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2) on clinician-collected specimens (HC2-C) and of careHPV on clinician-collected (careHPV-C) and self-collected specimens (careHPV-S) at a series of cutoff points to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe diagnoses (CIN3+) were determined. Boldface type highlights the performance at the optimal cutoff point; underlined values highlight the manufacturer-recommended cutoff point.

The clinical performance of the three tests in detection of CIN2+ is similar to that of CIN3+ (Table 2). The optimal cutoff points were 1.40, 1.68, and 0.80 for HC2-C, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio of Hybrid Capture 2 on clinician-collected specimens and of careHPV on clinician-collected and self-collected specimens to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or more severe diagnosesa

| Test and cutoff point | No. of HPV-positive specimens (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | PLR | NLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC2-C | |||||||

| 0.50 | 2,085 (21.3) | 98.59 | 80.41 | 10.07 | 99.96 | 5.03 | 0.018 |

| 1.00 | 1,457 (14.9) | 96.24 | 86.92 | 14.07 | 99.90 | 7.36 | 0.043 |

| 1.40* | 1,341 (13.7) | 96.24 | 88.13 | 15.29 | 99.91 | 8.11 | 0.043 |

| careHPV-C | |||||||

| 0.50 | 1,982 (20.3) | 95.31 | 81.41 | 10.24 | 99.87 | 5.13 | 0.058 |

| 1.00 | 1,401 (14.3) | 92.02 | 87.41 | 13.99 | 99.80 | 7.31 | 0.091 |

| 1.68 | 1,215 (12.4) | 91.08 | 89.33 | 15.97 | 99.78 | 8.54 | 0.100 |

| 1.74* | 1,206 (12.3) | 90.61 | 89.42 | 16.00 | 99.77 | 8.56 | 0.105 |

| careHPV-S | |||||||

| 0.50 | 2,032 (20.8) | 84.98 | 80.66 | 8.91 | 99.59 | 4.39 | 0.186 |

| 0.80 | 1,522 (15.6) | 80.75 | 85.90 | 11.30 | 99.50 | 5.73 | 0.224 |

| 0.85* | 1,485 (15.2) | 80.28 | 86.27 | 11.52 | 99.49 | 5.85 | 0.229 |

| 1.00 | 1,398 (14.3) | 79.34 | 87.16 | 12.09 | 99.48 | 6.18 | 0.237 |

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2) on clinician-collected specimens (HC2-C) and of careHPV on clinician-collected (careHPV-C) and self-collected specimens (careHPV-S) at a series of cutoff points to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or more severe diagnoses (CIN2+) were determined. Boldface type highlights the performance at the optimal cutoff point; underlined values highlight the manufacturer-recommended cutoff point. The area under the curve for HC2-C was 0.956 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.947 to 0.966), for careHPV-C was 0.946 (95% CI = 0.933 to 0.959), and for careHPV-S was 0.875 (95% CI = 0.852 to 0.898). *, Optimal cutoff point for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe diagnoses.

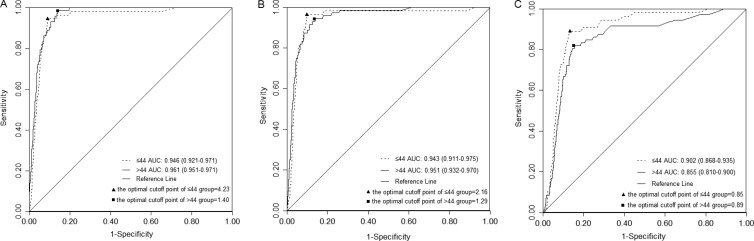

We conducted a simple stratified analysis by median age (i.e., 25 to 44 and 45 to 65) to explore the impact of age on the optimal cutoff point and performance (Fig. 2 and Table 3). For each test, no statistical significance between the AUCs of younger and older women was found (0.946 versus 0.961 [P = 0.251] for HC2-C, 0.943 versus 0.951 [P = 0.688] for careHPV-C, and 0.902 versus 0.855 [P = 0.105] for careHPV-S), but the optimal cutoff points were different (4.23 versus 1.40 for HC2-C and 2.16 versus 1.29 for careHPV-C) except careHPV-S (0.85 versus 0.89). Higher cutoff points in both age groups for tests using clinician-collected specimens improved accuracy by improving specificity (i.e., reducing the false-positive fraction). Conversely, for careHPV-S, slightly lower cutoff points in both age groups improved accuracy by increasing sensitivity (i.e., reducing the false-negative fraction).

FIG 2.

ROC curves of HC2 on clinician-collected specimens and of careHPV on clinician-collected and self-collected specimens to detect CIN3+ by age. (A) ROC curve of HC2 on clinician-collected specimens by age. The optimal cutoff point for women younger than 44 years is 4.23, with a sensitivity of 94.55% (95% CI = 85.15 to 98.13) and a specificity of 90.67% (95% CI = 89.85 to 91.43%); the optimal cutoff point is 1.40 in women older than 44 years, with the sensitivity of 98.61% (95% CI = 92.54 to 99.75%) and a specificity of 86.09% (95% CI = 85.04 to 87.07%). (B) ROC curve of careHPV on clinician-collected specimens by age. The optimal cutoff point for women younger than 44 years is 2.16, with a sensitivity of 96.36% (95% CI = 87.68 to 99.00%) and a specificity of 90.42% (95% CI = 89.59 to 91.19%); the optimal cutoff point is 1.29 in women older than 44 years, a the sensitivity of 94.44% (95% CI = 86.57 to 97.82%) and a specificity of 86.44% (95% CI = 85.41 to 87.41%). (C) ROC curve of careHPV on self-collected specimens by age. The optimal cutoff point for women younger than 44 years is 0.85, with a sensitivity of 89.09% (95% CI = 78.17 to 94.90%) and a specificity of 86.78% (95% CI = 85.83 to 87.68%); the optimal cutoff point is 0.89 in women older than 44 years, with a sensitivity of 81.94% (95% CI = 71.52 to 89.13%) and a specificity of 84.73% (95% CI = 83.65 to 85.75%). The solid triangle indicates the optimal cutoff point for each test in women younger than 44 years, and the solid square indicates the optimal cutoff point for each test in women older than 44 years. The ranges in parentheses are the 95% CIs of the AUC. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; CIN3+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more server; AUC, area under ROC curve.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio of Hybrid Capture 2 on clinician-collected specimens and of careHPV on clinician-collected and self-collected specimens at a series of cutoff points to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe diagnoses (CIN3+), stratified by median age (≤44 years [n = 5,221] and >44 years [n = 4,564])a

| Test, age group (yr), and cutoff point | No. of HPV-positive specimens (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | PLR | NLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC2-C | |||||||

| ≤44 | |||||||

| 0.50 | 960 (18.4) | 96.36 | 82.44 | 5.52 | 99.95 | 5.49 | 0.044 |

| 1.00 | 688 (13.2) | 94.55 | 87.69 | 7.56 | 99.93 | 7.68 | 0.062 |

| 2.00 | 601 (11.5) | 94.55 | 89.37 | 8.65 | 99.94 | 8.90 | 0.061 |

| 4.00 | 538 (10.3) | 94.55 | 90.59 | 9.67 | 99.94 | 10.05 | 0.060 |

| 4.23 | 534 (10.2) | 94.55 | 90.67 | 9.74 | 99.94 | 10.13 | 0.060 |

| 10.0 | 453 (8.7) | 85.45 | 92.14 | 10.38 | 99.83 | 10.87 | 0.158 |

| >44 | |||||||

| 0.50 | 1125 (24.6) | 100.00 | 76.56 | 6.40 | 100.00 | 4.27 | 0.000 |

| 1.00 | 769 (16.8) | 98.61 | 84.46 | 9.23 | 99.97 | 6.35 | 0.016 |

| 1.40 | 696 (15.2) | 98.61 | 86.09 | 10.20 | 99.97 | 7.09 | 0.016 |

| 2.00 | 656 (14.4) | 95.83 | 86.93 | 10.52 | 99.92 | 7.33 | 0.048 |

| 4.00 | 575 (12.6) | 93.06 | 88.69 | 11.65 | 99.87 | 8.23 | 0.078 |

| 10.00 | 489 (10.7) | 88.89 | 90.54 | 13.09 | 99.80 | 9.40 | 0.123 |

| careHPV-C | |||||||

| ≤44 | |||||||

| 0.50 | 999 (19.1) | 98.18 | 81.71 | 5.41 | 99.98 | 5.37 | 0.022 |

| 1.00 | 669 (12.8) | 96.36 | 88.08 | 7.92 | 99.96 | 8.08 | 0.041 |

| 2.00 | 564 (10.8) | 96.36 | 90.11 | 9.40 | 99.96 | 9.74 | 0.040 |

| 2.16 | 548 (10.5) | 96.36 | 90.42 | 9.67 | 99.96 | 10.06 | 0.040 |

| 4.00 | 481 (9.2) | 89.09 | 91.64 | 10.19 | 99.87 | 10.65 | 0.119 |

| 10.00 | 394 (7.5) | 81.82 | 93.24 | 11.42 | 99.79 | 12.11 | 0.195 |

| >44 | |||||||

| 0.50 | 983 (21.5) | 95.83 | 79.65 | 7.02 | 99.92 | 4.71 | 0.052 |

| 1.00 | 732 (16.0) | 94.44 | 85.22 | 9.29 | 99.90 | 6.39 | 0.065 |

| 1.29 | 677 (14.8) | 94.44 | 86.44 | 10.04 | 99.90 | 6.97 | 0.064 |

| 2.00 | 601 (13.2) | 91.67 | 87.97 | 10.86 | 99.85 | 7.62 | 0.095 |

| 4.00 | 523 (11.4) | 88.89 | 89.81 | 12.24 | 99.80 | 8.73 | 0.124 |

| 10.0 | 429 (9.4) | 84.72 | 91.83 | 14.22 | 99.73 | 10.37 | 0.167 |

| careHPV-S | |||||||

| ≤44 | |||||||

| 0.50 | 997 (19.1) | 89.09 | 81.65 | 4.92 | 99.86 | 4.86 | 0.134 |

| 0.85 | 732 (14.0) | 89.09 | 86.78 | 6.69 | 99.87 | 6.74 | 0.126 |

| 1.00 | 693 (13.2) | 87.27 | 87.54 | 6.93 | 99.85 | 7.00 | 0.145 |

| 2.00 | 550 (10.5) | 72.73 | 90.15 | 7.27 | 99.68 | 7.38 | 0.303 |

| 4.00 | 446 (8.5) | 67.27 | 92.10 | 8.30 | 99.62 | 8.51 | 0.355 |

| 10.00 | 323 (6.2) | 43.64 | 94.22 | 7.43 | 99.37 | 7.55 | 0.598 |

| >44 | |||||||

| 0.50 | 1044 (22.8) | 84.72 | 78.18 | 5.84 | 99.69 | 3.88 | 0.195 |

| 0.89 | 745 (16.3) | 81.94 | 84.73 | 7.92 | 99.66 | 5.37 | 0.213 |

| 1.00 | 721 (15.7) | 80.56 | 85.29 | 8.04 | 99.64 | 5.48 | 0.228 |

| 2.00 | 585 (12.8) | 72.22 | 88.17 | 8.89 | 99.50 | 6.11 | 0.315 |

| 4.00 | 464 (10.1) | 59.72 | 90.66 | 9.27 | 99.30 | 6.39 | 0.444 |

| 10.00 | 350 (7.6) | 43.06 | 92.92 | 8.86 | 99.03 | 6.08 | 0.613 |

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2) on clinician-collected specimens (HC2-C) and of careHPV on clinician-collected (careHPV-C) and self-collected specimens (careHPV-S) at a series of cutoff points to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe diagnoses (CIN3+), stratified by median age (≤44 years [n = 5,221] and >44 years [n = 4,564]), were determined. Boldface type highlights the performance at the optimal cutoff point; underlined values highlight the manufacturer-recommended cutoff point.

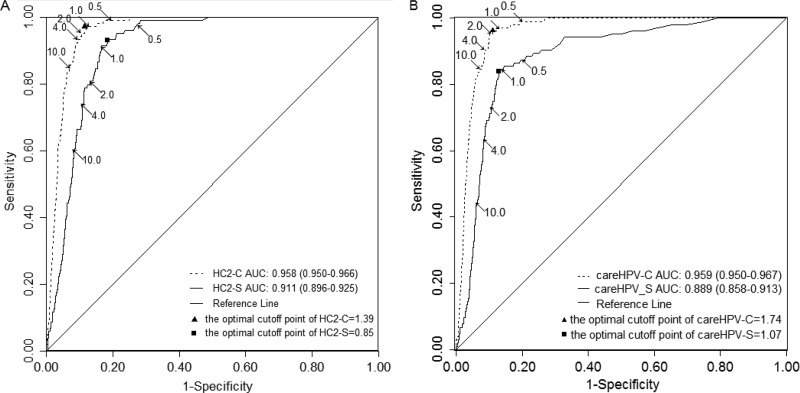

In a subset analysis restricted to the START-UP project, for which the HC2-S was also available, we observed the optimal cutoff point for HC-S was lower than that of HC2-C, as it was for careHPV-S and careHPV-C, and the sensitivity of HC2-S was lower than that of HC2-C (Fig. 3). At a given cutoff point, HC2-S was more sensitive but less specific than careHPV-S, and at cutoff points for comparable sensitivity or specificity, HC2-S had superior specificity or sensitivity, respectively, compared to careHPV-S.

FIG 3.

ROC curves of HC2 and careHPV on clinician-collected and self-collected specimens to detect CIN3+. (A) ROC curve of HC2 on clinician- and self-collected specimens. (B) ROC curve of careHPV on clinician- and self-collected specimens. The analysis is for START-UP project only. The curves show the various combinations of cutoff points of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 10.0 as indicated by arrows. The solid triangle is the optimal cutoff point on clinician-collected specimens and the solid square is the optimal cutoff point on self-collected specimens for each test. The ranges in parentheses are the 95% CIs of the AUC. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; CIN3+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or above; AUC, area under ROC curve.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the optimal cutoff point of the new, rapid HPV DNA test, careHPV, with a large number of CIN3+ endpoints. In general, the clinical performance of careHPV test on clinician-collected specimens was similar to that of the HC2 test on clinician-collected specimens at the same positive cutoff point, while careHPV testing of self-collected specimens showed good but lower test accuracy than the use of clinician-collected specimens, presumably due to poorer sampling of the cervical lesions and/or increased sampling of clinically irrelevant vaginal and vulvar HPV infections. The poorer clinical performance of HPV DNA testing on self-collected specimens versus clinician-collected specimens observed in this analysis for careHPV on all specimens, as well as HC2 and careHPV on the subset of specimens from START-UP project, is consistent with other studies conducted in China (17) and elsewhere (22, 23).

Although the threshold for careHPV has been set by the manufacturer, it is worth considering the programmatic implications of such a decision. In this population, at the 1.0 cutoff point for careHPV-C, 1,432 out of every 10,000 women screened would be labeled as HPV positive and required clinical follow-up, within the HPV-positive women only 14.0% having CIN2+ and 8.6% having CIN3+ who need treatment. Lowering the cutoff point of careHPV-C to 0.5 to achieve the same sensitivity as HC2-C would result in an additional ∼600 women being labeled as HPV positive to find 2 additional CIN3+ per 10,000 women screened, or approximately 300 false positives to every one true positive (i.e., CIN3+). Conversely, raising the cutoff point to 2.0 would result in missing 2 CIN3+ per 10,000 women but would reduce the number of false positives by 240 per 10,000, or an ∼17% reduction in the referral rate for clinical management. Translated into ∼500 million women who need to be screened in rural China, nearly 12 million of them would be rid of unnecessary referrals. In that case, considerable health resources would be saved. Based on these data, we suggest that increasing the cutoff point for careHPV-C to 2.0 may represent a good trade-off for LMICs where there are limited numbers of clinical personnel to provide the necessary clinical management.

Although HPV tests on self-collected specimens would not perform as well as the tests on clinician-collected specimens, it could be used as a complementary tool for the current cervical cancer screening programs to reach women who cannot access clinics (17). We observed a moderate sensitivity of 83.46% and specificity of 86.49% in detecting CIN3+ at 1.0 positive cutoff point by careHPV-S. Increasing the cutoff point resulted in significant reductions in sensitivity. Therefore, we recommended the current use of 1.0 cutoff point as the best threshold for careHPV test for self-collected specimens.

Since missing an invasive cancer has more clinical impact than missing a CIN3, which might be picked up in a second round of screening, we paid attention to each invasive cancer. First, all 11 women with invasive cancer were asymptomatic, and 3 of them were even negative for an VIA test. Second, we found that of the 11 invasive cancers, none were missed by careHPV-C at the 2.0 cutoff point, and two were missed by careHPV-S at the 1.0 cutoff point. Therefore, we hypothesized that the missed cancers by careHPV-S testing were the likely result of poorer sampling of the cancers (22, 23).

Cervical cancer is a disease that progresses gradually from HPV infection, which includes cytologic (e.g., low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion) and histologic (CIN1) manifestations, to cervical precancer, best represented by CIN3, and finally to invasive cervical cancer over a period of time approximately 20 to 25 years on average (24). We wanted to see whether different clinical performances and cutoff points could be found in women with different age groups without the interference from the disease prevalence (25). This may be relevant to programs that target narrower age ranges that address programmatic considerations, such as focusing on younger ages to find more CIN3 and less cancer because of a lack of cancer management health services. Therefore, we stratified our data by median age (44 years) with 1.1% CIN3+ prevalence in the younger group and 1.6% in the older group to maximize the statistical power. For all tests, the sensitivity did not vary in two age groups at a change in cutoff point from 0.5 to 10.0, while the specificity was consistently higher in women younger than 44 years. This is in line with a pooled analysis previously done in China (26). Since only persistent HPV infections could lead to severe cervical lesions (27) and younger women are easier to clear their infections (28), a higher cutoff point may be adopted in younger women to reduce false-positive rates. In our study, raising the cutoff point in younger women, we may definitely observe an increase in specificity without much decrease in sensitivity. The same sensitivity as 1.0 RLU/CO for each test among the total population could be reached by only shifting the cutoff point to 4.0 for HC2-C and 2.0 for careHPV-C among women younger than 44 years (data not show). However, the combination would lead to significant increase in specificity and decrease in test positive rate, which, in turn, could reduce at least 1% overdiagnosis and 1% false positives compared to the performance at the 1.0 RLU/CO cutoff point among the total population.

Based on the fact that sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV only reflect population characteristics and are not independent of disease prevalence, we also assessed the likelihood ratios of each test which could be used at the individual level directly (29). We found that the PLR of careHPV-C at the 2.0 cutoff point and careHPV-S at the 1.0 cutoff point were 8.65 and 6.24, respectively, which increased the probability of cervical precancer and cancer ca. 40 and 35% (30) when the tests showed positive results. In that case, the cutoff point could play an important role at both population and individual levels. Furthermore, Meijer et al. (31) raised the requirements of a new HPV test: (i) the clinical sensitivity of the new test for CIN2+ were not <90% of the HC2, (ii) the clinical specificity for CIN2+ were not <98% of the HC2, and (iii) the agreement with HC2 were not <87%. In our study, when using the performance of HC2-C at the 1.0 cutoff point to detect CIN3+ as the standard, the performance of careHPV-C at the 2.0 cutoff point met all of the requirements. However, the sensitivity at the 1.0 cutoff point of careHPV-S was 86.2% of HC2's sensitivity (83.46% versus 96.85%), while the specificity and concordance can achieve the requirements. As a consequence, we can use the 2.0 cutoff point for the careHPV-C test and the 1.0 cutoff point for the careHPV-S in the cervical cancer screening practice to get a relatively good performance.

An important limitation of our study is that not every single participant was biopsied, which could result in missing CIN2+ or CIN3+ cases. Therefore, we may have overestimated the clinical sensitivity of the HPV DNA tests. Our results are deemed to be relatively rather than absolutely accurate. However, we took the following measures to minimize the verification bias. Participants with any positive result of screening tests had at least one biopsy result. In START, a combination of HPV DNA tests, LBC, VIA, and colposcopy was used to determine the results which screened as negative, which, in turn, lowered the risk of losing any high-grade cervical lesions (32). In START-UP, although no cytology was performed, the combination of six tests (i.e., VIA, OncoE6, HC2-C, HC2-S, careHPV-C, and careHPV-S) could act as a safeguard against sending all CIN2+ to colposcopy. Meanwhile, we randomly selected 10% of results that screen negative for colposcopy evaluation and found no cervical lesions in those women. We acknowledge that the HPV prevalence and CIN3+ prevalence are age dependent, but the stratified analysis by median age could not provide enough information on the impact of age. Larger studies or pooling of more studies will be necessary to look at the effects of age on the performance of careHPV in detail and the age-specific optimal cutoff points.

In conclusion, our study found careHPV testing on clinician-collected specimens to be as accurate as HC2 testing on clinician-collected specimens and better than careHPV testing on self-collected specimens. The optimal cutoff points of careHPV were 2.0 on clinician-collected specimens and 1.0 on self-collected specimens. Raising the cutoff point of HPV tests, as administered by clinicians, can lead to better clinical results among younger females. With its low cost, high accuracy, and shorter operating time, careHPV test is a viable alternative for large scale cervical cancer prevention screening programs in China and in other developing countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the members of these two projects from PATH, CICAMS, and the Maternal and Children's Hospitals in the Xiangyuan, Wuxiang, Yangcheng, Xinmi, and Tonggu counties of China. We also thank all of the participants in these two studies.

The START and START-UP Projects are funded by grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

J.J. was the director of the study and received all of the tests used in the study as a donation from the manufacturing companies (Qiagen and Arbor Vita Corp.). M.H.S. is a consultant in a clinical trial design and implementation and/or has served as an expert pathologist for clinical trials for Merck, Roche, Becton Dickinson, Qiagen, Gen-Probe, Hologic, Ventana Medical Systems, and MTM Laboratories. P.E.C. has received commercial HPV tests for research at a reduced or no cost from Roche, Qiagen, Norchip, and MTM. P.E.C. is a paid consultant for Becton Dickinson, GE Healthcare, and Cepheid and has received a speaker's honorarium from Roche. P.E.C. is a paid consultant for Immunexpress on sepsis diagnostics and is compensated as a member of a Merck Data and Safety Monitoring Board for HPV vaccines. L.-N.K., Y.-L.Q., F.-H.Z., W.C., M.V., X.Z., P.B., P.P., P.B., R.P., J.L., and F.C. declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, Walter SD, Hanley J, Ferenczy A, Ratnam S, Coutlée F, Franco EL, Canadian Cervical Cancer Screening Trial Study Group 2007. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:1579–1588. 10.1056/NEJMoa071430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sankaranarayanan R, Budukh AM, Rajkumar R. 2001. Effective screening programmes for cervical cancer in low- and middle-income developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 79:954–962 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denny L, Sankaranarayanan R. 2006. Secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 94:S65–S70. 10.1016/S0020-7292(07)60012-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, van Kemenade FJ, Bulkmans NW, Heideman DA, Kenter GG, Cuzick J, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ. 2012. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 13:78–88. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70296-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, Confortini M, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro A, Ghiringhello B, Girlando S, Gillio-Tos A, De Marco L, Naldoni C, Pierotti P, Rizzolo R, Schincaglia P, Zorzi M, Zappa M, Segnan N, Cuzick J, New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group 2010. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 11:249–257. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM, Hingmire S, Malvi SG, Thorat R, Kothari A, Chinoy R, Kelkar R, Kane S, Desai S, Keskar VR, Rajeshwarkar R, Panse N, Dinshaw KA. 2009. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:1385–1394. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenzi AT, Fregnani JH, Possati-Resende JC, Neto CS, Villa LL, Longatto-Filho A. 2013. Self-collection for high-risk HPV detection in Brazilian women using the careHPVTM test. Gynecol. Oncol. 131:131–134. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.07.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao YL, Sellors JW, Eder PS, Bao YP, Lim JM, Zhao FH, Weigl B, Zhang WH, Peck RB, Li L, Chen F, Pan QJ, Lorincz AT. 2008. A new HPV-DNA test for cervical-cancer screening in developing regions: a cross-sectional study of clinical accuracy in rural China. Lancet Oncol. 9:929–936. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70210-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao FH, Jeronimo J, Qiao YL, Schweizer J, Chen W, Valdez M, Lu P, Zhang X, Kang LN, Bansil P, Paul P, Mahoney C, Berard-Bergery M, Bai P, Peck R, Li J, Chen F, Stoler MH, Castle PE. 2013. An evaluation of novel, lower-cost molecular screening tests for human papillomavirus in rural China. Cancer Prev. Res. 6:938–948. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gage JC, Ajenifuja KO, Wentzensen N, Adepiti AC, Stoler M, Eder PS, Bell L, Shrestha N, Eklund C, Reilly M, Hutchinson M, Wacholder S, Castle PE, Burk RD, Schiffman M. 2012. Effectiveness of a simple rapid human papillomavirus DNA test in rural Nigeria. Int. J. Cancer 131:2903–2909. 10.1002/ijc.27563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ngou J, Magooa MP, Gilham C, Djigma F, Didelot MN, Kelly H, Yonli A, Sawadogo B, Lewis DA, Delany-Moretlwe S, Mayaud P, Segondy M, HARP Study Group 2013. Comparison of careHPV and hybrid capture 2 assays for detection of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in cervical samples from HIV-1-infected African women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:4240–4242. 10.1128/JCM.02144-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trope LA, Chumworathayi B, Blumenthal PD. 2013. Feasibility of community-based careHPV for cervical cancer prevention in rural Thailand. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 17:315–319. 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31826b7b70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin CE, Sellors J, Shi JF, Ma L, Qiao YL, Ortendahl J, O'Shea MK, Goldie SJ. 2010. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cervical cancer prevention based on a rapid human papillomavirus screening test in a high-risk region of China. Int. J. Cancer 127:1404–1411. 10.1002/ijc.25150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clavel C, Masure M, Bory JP, Putaud I, Mangeonjean C, Lorenzato M, Nazeyrollas P, Gabriel R, Quereux C, Birembaut P. 2001. Human papillomavirus testing in primary screening for the detection of high-grade cervical lesions: a study of 7932 women. Br. J. Cancer 84:1616–1623. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulmala SM, Syrjänen S, Shabalova I, Petrovichev N, Kozachenko V, Podistov J, Ivanchenko O, Zakharenko S, Nerovjna R, Kljukina L, Branovskaja M, Grunberga V, Juschenko A, Tosi P, Santopietro R, Syrjänen K. 2004. Human papillomavirus testing with the hybrid capture 2 assay and PCR as screening tools. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2470–2475. 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2470-2475.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sargent A, Bailey A, Turner A, Almonte M, Gilham C, Baysson H, Peto J, Roberts C, Thomson C, Desai M, Mather J, Kitchener H. 2010. Optimal threshold for a positive hybrid capture 2 test for detection of human papillomavirus: data from the ARTISTIC trial. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:554–558. 10.1128/JCM.00896-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao FH, Lewkowitz AK, Chen F, Lin MJ, Hu SY, Zhang X, Pan QJ, Ma JF, Niyazi M, Li CQ, Li SM, Smith JS, Belinson JL, Qiao YL, Castle PE. 2012. Pooled analysis of a self-sampling HPV DNA test as a cervical cancer primary screening method. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 104:178–188. 10.1093/jnci/djr532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, Suonio E, Dillner L, Minozzi S, Bellisario C, Banzi R, Zhao FH, Hillemanns P, Anttila A. 2014. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 15:172–183. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70570-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazcano-Ponce E, Lorincz AT, Cruz-Valdez A, Salmerón J, Uribe P, Velasco-Mondragón E, Nevarez PH, Acosta RD, Hernández-Avila M. 2011. Self-collection of vaginal specimens for human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer prevention (MARCH): a community-based randomised controlled trial. Lancet 378:1868–1873. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61522-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorincz A, Castanon A, Wey Lim AW, Sasieni P. 2013. New strategies for human papillomavirus-based cervical screening. Womens Health 9:443–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pretorius RG, Zhang WH, Belinson JL, Huang MN, Wu LY, Zhang X, Qiao YL. 2004. Colposcopically directed biopsy, random cervical biopsy, and endocervical curettage in the diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia II or worse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 191:430–434. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia F, Barker B, Santos C, Brown EM, Nuño T, Giuliano A, Davis J. 2003. Cross-sectional study of patient- and physician-collected cervical cytology and human papillomavirus. Obstet. Gynecol. 102:266–272. 10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00517-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sellors JW, Lorincz AT, Mahony JB, Mielzynska I, Lytwyn A, Roth P, Howard M, Chong S, Daya D, Chapman W, Chernesky M. 2000. Comparison of self-collected vaginal, vulvar, and urine samples with physician-collected cervical samples for human papillomavirus testing to detect high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. CMAJ 163:513–518 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, Garcia FA, Moriarty AT, Waxman AG, Wilbur DC, Wentzensen N, Downs LS, Jr, Spitzer M, Moscicki AB, Franco EL, Stoler MH, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Myers ER, American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society for Clinical Pathology 2012. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 137:516–542. 10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leeflang MM, Bossuyt PM, Irwig L. 2009. Diagnostic test accuracy may vary with prevalence: implications for evidence-based diagnosis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62:5–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao FH, Lin MJ, Chen F, Hu SY, Zhang R, Belinson JL, Sellors JW, Franceschi S, Qiao YL, Castle PE, Cervical Cancer Screening Group in China 2010. Performance of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA testing as a primary screen for cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from 17 population-based studies from China. Lancet Oncol. 11:1160–1171. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70256-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. 2007. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 370:890–907. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai CH, Chao A, Chang CJ, Chao FY, Huang HJ, Hsueh S, Lin CT, Cheng HH, Huang CC, Yang JE, Wu TI, Chou HH, Chang TC. 2008. Host and viral factors in relation to clearance of human papillomavirus infection: a cohort study in Taiwan. Int. J. Cancer 123:1685–1692. 10.1002/ijc.23679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giard RWM, Hermans J. 1996. The diagnostic information of tests for the detection of cancer: the usefulness of the likelihood ratio concept. Eur. J. Cancer 32A:2042–2048. 10.1016/S0959-8049(96)00282-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGee S. 2002. Simplifying likelihood ratios. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 17:646–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Castle PE, Hesselink AT, Franco EL, Ronco G, Arbyn M, Bosch FX, Cuzick J, Dillner J, Heideman DA, Snijders PJ. 2009. Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int. J. Cancer 124:516–520. 10.1002/ijc.24010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright TC, Jr, Schiffman M. 2003. Adding a test for human papillomavirus DNA to cervical-cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:489–490. 10.1056/NEJMp020178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]