Abstract

Endotracheal/endobronchial metastasis, which is from either primary bronchogenic carcinoma or a tumor of non-pulmonary origin, is a rare but life-threatening condition. Among the different locations in the tracheobronchial tree, the trachea is an extremely rare location for metastasis from extrapulmonary tumor. To the best of our knowledge, endotracheal metastasis that was clearly visualized by F-18 FDG PET/CT has not been previously reported. We herein report on a patient with a FDG-avid endotracheal eccentric mass that was confirmed as metastasis from rectal cancer.

Keywords: FDG PET-CT, Endotreacheal metastasis, Colorectal cancer

Introduction

The lung is a common organ for metastases from extrapulmonary tumors, and lung parenchymal metastasis sometimes infiltrates into the respiratory tree. On the other hand, endotracheal/endobronchial metastasis (EEM) is usually defined as primary involvement of the tracheobronchial epithelium, and this is a rare finding. Sorenson et al. reported the trachea is only involved by 5% of all the tumors in the respiratory tree [1]. Chest computed tomography (CT) is a rapidly improving modality, but it is not always able to find luminal lesions. Florine-18 (F-18) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) is a valuable modality in the field of oncology, yet there have been limited reports about a definite FDG-avid endotracheal metastatic tumor.

Case Report

A 76-year-old male patient was admitted due to dyspnea. He had been previously diagnosed with rectal cancer in April 2003. He underwent laparoscopic anterior resection for moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with a mucin component and perirectal lymph node metastases (pT3N2). The tumor was 6 × 4 cm in size with invasion to the venous, angiolymphatic and perineural spaces. In December 2003, ileostomy repair was performed, and subsequently five cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy (fluorouracil + leucovorin) were administered. The patient had a history of smoking (40 pack-years) and a long history of alcohol ingestion (10 times/month × 40 years), but he denied any significant family medical history or other past medical history. On 11 September 2007, RUL lobectomy and RLL wedge resection of the lung were done due to metastatic adenocarcinoma, and eight cycles of adjuvant capecitabine (Xeloda) treatment were performed until March 2008. In December 2008, he developed pulmonary thromboembolism in the bilateral lower lobes, and his symptom resolved with anticoagulant therapy. In March 2010, he was admitted because of recurred dyspnea. His vital signs were stable, and his physical examination was normal. F-18 FDG PET-CT showed a 1.5 × 1.5 cm sized FDG-avid RML mass (maxSUV = 3.3) and an eccentric mass in the left distal tracheal wall (Fig. 1a, b and d). Retrospectively, we found an endotracheal mass of the same size in the same location on the chest CT performed 2 weeks previously, but it was not recognized at that time. On bronchoscopy, there was a 2-cm-long eccentric mass in the left side wall of the distal trachea (Fig. 1c), and this was later revealed as metastatic adenocarcinoma. After 3 months of chemotherapy with oxaliplatin/capecitabine (Enoxatin/Xeloda), the lesion shrank greatly in size, as seen on CT (Fig. 2).

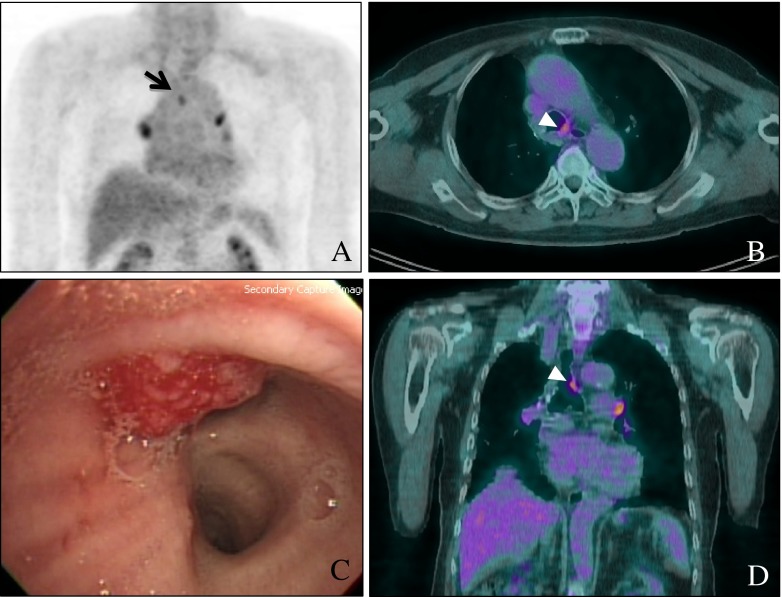

Fig. 1.

Fluorine (F)-18 Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) maximal intensity projection (MIP) (a), axial (b) and coronal (d) images of this patient show a FDG-avid endotracheal mass (maxSUV 2.4); (c) shows the bronchoscopic findings, and the mass was later revealed to be metastatic adenocarcinoma originating from rectal cancer

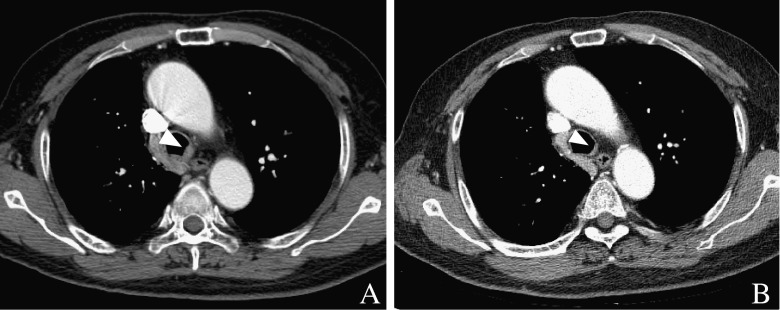

Fig. 2.

The enhanced chest CT axial and coronal images at a 3-month interval. (a) Shows the initial axial image of the endotracheal mass and (b) is the same image 3 months later. The initial mass, which is FDG-avid, is enhanced similarly to the adjacent azygous vein, and it could be regarded as a vascular structure in the mediastinum. The endotracheal mass was much reduced in size after chemotherapy

Discussion

EEM is usually regarded as a bronchoscopically diagnosed metastatic involvement of the tracheobronchial tree, and the tumor originates from a histolgically verified extrapulmonary primary malignancy. The trachea is involved in only 5% of EEMs [1], and tracheal metastasis is also extremely rare in patients with primary lung cancer. Chong et al. reported only 6 patients with EEM out of 1,372 (0.44%) patients with surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer [4].

The common primary neoplasms causing EEM are breast, kidney and colorectal cancers [1, 6]. Sarcoma, uterine cervix cancer and melanoma are also among the most frequent primaries that cause EEM. Rare primary diagnoses include cancers of the thyroid gland, urinary bladder, testicle, prostate gland, uterine corpus, penis, head and neck, salivary glands, ovary, stomach, liver and olfactory nerve, plasmacytoma, malignant chondroid syringoma, ampullary adenoma and neuroblastoma [1, 3].

One-third of EEM patients have two or more pulmonary symptoms of cough, dyspnea and hemoptysis. Twenty percent of the patients show no symptoms. Chest X-ray findings are mostly abnormal, and frequent findings are atelectasis, visible tumor and multiple nodules. The symptoms and X-ray findings are all non-specific [1].

Even though this current patient showed concurrent lung metastasis, it has been reported that 27% of the patients have EEM as the only manifestation of malignant disease without other signs of disease dissemination from the previously treated extrapulmonary primary tumor [1]. The average time till diagnosing EEM is 4 years after the initial diagnosis of the primary neoplasm, which is a relatively long lead time compared to the average progression in these solid tumors. In our patient, the lead time was also 5 years after the initial confirmation of rectal cancer [1], yet the cause of the EEM was not definitely proved.

In this patient, the F-18 FDG PET/CT showed FDG-avidity (maxSUV = 2.4) in the endotracheal mass, but the radiologists could not recognize this lesion on chest CT. If an endotracheal tumor is well enhanced, then it can mimic adjacent vascular structures in the mediastinum [7], so it can be easily missed. F-18 FDG PET/CT can recognize this lesion without confusing it with vascular structures as well as other benign lesions such as phlegm [4].

The results from other studies [1, 2] suggest that EEM may not necessarily indicate a poor outcome and should not be a deterrent to surgery. Surgery for EEM should be considered if it is technically feasible and if the performance status is not too poor [5]. Good palliation has also been obtained with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, brachytherapy and cryotherapy. The intraluminal polypoid mass of our patient was nearly resolved with chemotherapyEnoxatin/Xeloda (oxaliplatin/capecitadine), and he is still under treatment.

The possibility of EEM should be considered in the differential diagnosis of respiratory obstructive symptoms, even if the patient's symptoms have other causes, and especially if the patient has a prior history of malignancy. In addition, EEM by itself is a life-threatening condition, yet it has a relatively good prognosis. Therefore, clinical suspicion is of paramount importance for routine surveillance of metastasis in cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sorensen JB. Endobronchial metastases from extrapulmonary solid tumors. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:73–79. doi: 10.1080/02841860310018053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romain C. Endobronchial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinomas: clinical and endoscopic characteristics and patient prognosis. Oncology. 2007;73:395–400. doi: 10.1159/000136794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akoglu S. Endobronchial metastases from extrathoracic malignancies. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22:587–591. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-5787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong S. Tracheal metastasis of lung cancer: CT findings in six patients. AJR. 2006;186:220–224. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepherd MP. Endobronchial metastatic disease. Thorax. 1982;37:362–365. doi: 10.1136/thx.37.5.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgartner WA, Mark JB. Metastatic malignancies from distant sites to the tracheobronchial tree. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;79:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeung MY. Bronchial carcinoid tumors of the thorax: spectrum of radiologic findings. RadioGraphics. 2002;22:351–365. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.2.g02mr01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]