Abstract

Purpose

PET (positron emission tomography) is a noninvasive imaging technique, visualizing biological aspects in vivo. In animal models, the result of PET study can be affected more prominently than in humans by the animal conditions or drug pretreatment. We assessed the effects of anesthesia, body temperature, and pretreatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor on the results of [18F]N-3-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane ([18F]FP-CIT) PET in mice.

Methods

[18F]FP-CIT PET of C57BL/6 mice was performed in three different conditions: (1) anesthesia (isoflurane) with active warming (38°C) as a reference; (2) no anesthesia or warming; (3) anesthesia without warming at room temperature. Additional groups of mice pretreated with escalating doses of fluvoxamine (5, 20, 40, 80 mg/kg) were imaged in condition (1). The time activity curve and standardized uptake value of the striatum, cerebral cortex, and bone were compared among these conditions.

Results

In all conditions, radioactivities of the striatum and cortex tended to form a plateau after rapid uptake and washout, but that of bone tended to increase gradually. When anesthetized without any warming, all the mice developed hypothermia and showed reduced bone uptake with slightly increased striatal and cortical uptakes compared to the reference condition. In conditions without anesthesia, striatal and cortical uptakes were reduced, whereas the bone uptake showed no change. Pretreatment with fluvoxamine increased the striatal uptake and striatal specific to cortical non-specific uptake ratio, whereas the bone uptake was reduced.

Conclusion

Anesthesia, body temperature, and fluvoxamine affect the result of [18F]FP-CIT PET in mice by altering striatal and bone uptakes.

Keywords: [18F]FP-CIT, PET, Anesthesia, Temperature, Fluvoxamine, Mice

Introduction

PET is a noninvasive imaging technique using radiotracers to see and quantitatively measure various biological aspects of living subjects [1, 2]. Recent advances in PET technology have made it possible to image small animals [3]. Preclinical studies using small animal PET are rapidly increasing, since this modality makes it possible to image numerous biologic phenomena such as glucose metabolism, protein expression, neuroreceptor status, angiogenesis, hypoxia, apoptosis, and evaluation of treatment response in transgenic or disease models [4]. But the translation of animal studies into human requires caution because there are several differences between the species, such as metabolism. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of radiotracers in small animals may vary according to the species and also the animal conditions during the PET study. Generally, in vivo PET imaging of small animals, anesthesia is needed to prevent motion artifacts, and so is warming to prevent hypothermia or death of the animal [5–7]. However, anesthesia is known to have significant effects on the central nervous, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems [8]. An anesthetized mouse is particularly prone to hypothermia because of its high surface area-to-mass ratio. The effects of anesthesia and body temperature on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of radiotracers in mice may be more prominent than in humans since mice have approximately seven-fold higher basal metabolic rates per body weight than humans [9].

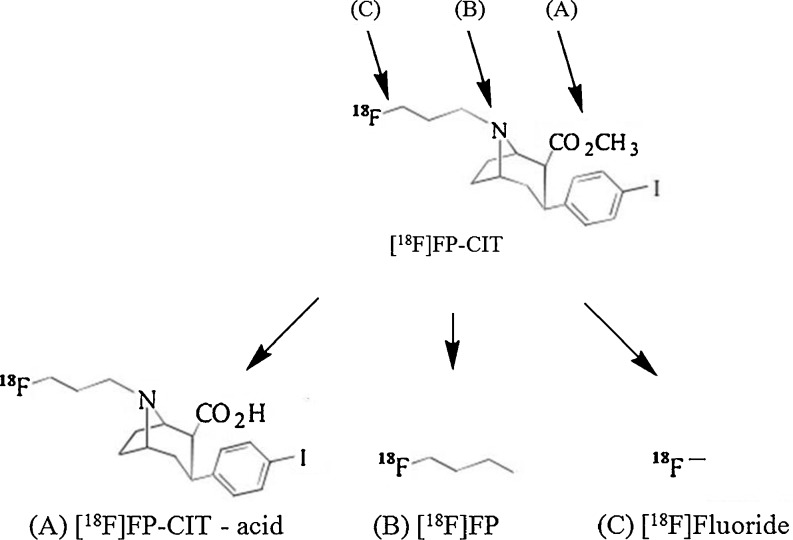

[18F]N-3-Fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane ([18F]FP-CIT) is a promising PET radiotracer for striatal dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging with several advantages including fast pharmacokinetics, relatively long half-life, hydrophilic metabolites, and high-resolution images of PET [10]. The radiometabolites of [18F]FP-CIT in vivo include the free carboxylic acid form of [18F]FP-CIT by esterase, [18F]fluoropropyl- by N-dealkylation, and [18F]fluoride ion by defluorination [11] (Fig. 1). Approximately 80–90 % of parent [18F]FP-CITs are rapidly metabolized into these polar radiometabolites [12], which cannot cross the blood–brain barrier, but the radioactivity of [18F]fluoride absorbed by bones such as the skull can spill into the neocortical region of the brain, which may compromise the results of PET [13]. Some of these metabolites are known to be formed primarily by the cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (CYP), which are easily affected by the metabolic condition of the animal, as mentioned above [14]. Thus, the inhibition of these metabolisms could improve the quality of the images and the quantitative analysis of [18F]FP-CIT PET because of the increase in net parent dose.

Fig. 1.

Possible radiometabolites of [18F]FP-CIT. (a) The hydrolysis of ester gives rise to [18F]FP-CIT acid, the major metabolite found in plasma. (b) The N-dealkylation by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes leads to the formation of [18F]fluoropropyl. (c) The defluorination by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes leads to the formation of [18F]fluoride

The defluorination of [18F]FCWAY, a 5-HT1A receptor radioligand, in rats was effectively prevented by pretreatment with miconazole, a CYP2E1 inhibitor [15]. Similarly, a different inhibitor, disulfiram, was fully effective in blocking the defluorination of [18F]FCWAY in human subjects, and as a result, brain 5-HT1A receptor imaging was greatly enhanced [16]. A successful application of this type of strategy will depend on the correct identification of the enzymes involved in the major step of radiotracer metabolism and the availability of safe and effective inhibitors of the identified enzymes. Recent studies of an adenosine A1 receptor radiotracer, [18F]CPFPX, demonstrated the feasibility of this approach. Oxidation of the cyclopentyl ring was established as the route of metabolism, and CYP1A2 was identified as the metabolizing enzyme [17]. Inhibition of this enzyme with fluvoxamine greatly reduced metabolism of radiotracers in human subjects [18].

[18F]FP-CIT, like other [18F]-labeled radiotracers mentioned above, may be metabolized by CYP isoenzymes. Fluvoxamine is not only a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) frequently used in depressive patients with Parkinson's disease (which is a main target disease of [18F]FP-CIT PET), but also an inhibitor of several CYP isoenzymes [19–21]. It could affect uptakes of [18F]FP-CIT in the brain directly, since [18F]FP-CIT binds not only to DAT, but also to serotonin transporters (SERT) [22]. Thus, we hypothesized that pretreatment with fluvoxamine could affect the results of [18F]FP-CIT PET in small animals and also in humans.

The goal of this study was to investigate the effects of the animal conditions during the PET study, such as the use of anesthetics, body temperature, and pretreatment with fluvoxamine, on the [18F]FP-CIT PET result.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation

All animal handling was performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and the Use Committee of the Asan Institute for Life Science. Twenty-four normal C57BL/6 mice aged 8 weeks and weighing 23–27 g were used.

Definition of Animal Conditions and Pretreatment with Fluvoxamine

Prescan animal conditions are summarized in Table 1. Group 1 was kept under anesthesia and warming (38°C) during 120 min of dynamic imaging, which was defined as a reference condition. Group 2 was kept alert without anesthesia or warming during the 90-min uptake period, and then anesthetized and warmed during the 30-min scan period to avoid hypothermia. Group 3 was kept under anesthesia at room temperature (20°C) without any warming.

Table 1.

Summary of animal conditions

| Group | n | Anesthesia | Warming | Fluvoxamine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2 | 4 | No | No | No |

| 3 | 4 | Yes | No | No |

| 4 ∼ 7 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

n Number of animals per group

Groups 4–7, for the evaluation of the influence of fluvoxamine pretreatment, were imaged under reference condition with pretreatment with escalating doses of fluvoxamine (5, 20, 40, 80 mg/kg). Fluvoxamine was continuously infused through the tail vein for 30 min before the injection of [18F]FP-CIT.

Mice were anesthetized by 2% isoflurane inhalation. Warming was achieved by placing a mouse on an electric warming pad at least 30 min before [18F]FP-CIT injection. Rectal temperature was measured with a thermistor probe during the study.

Radiopharmaceutical Preparation

[18F]FP-CIT was synthesized by a one-step method with a protic solvent system [23]. The radiochemical yield was 52.2 ± 4.5%, the chemical purity 98.5 ± 1.2% and the specific activity 64.4 ± 4.5 GBq/μmol.

Animal PET Imaging and Analysis

Approximately 3.7 MBq (2.4–5.5) of [18F]FP-CIT was injected into each mouse through the tail vein. The injection mass of FP-CIT ranged from 37.3 to 85.4 pmol.

PET scans were performed using the microPET Focus120 system (Siemens, Inc., Knoxville, TN, USA) with resolutions of 1.18 mm (radial), 1.13 mm (tangential), and 1.44 mm (axial) at the center of the field of view [24]. Twenty-eight-frame dynamic PET scans (6 × 0.5 min, 7 × 1 min, 5 × 2 min, 10 × 10 min) were acquired after injection for 120 min, except in group 2, in which only static images were acquired for 30 min at 90-min post-injection, to keep the mouse in an alert state without anesthesia during the uptake period. Regions of interest (ROIs) were manually drawn over the bilateral striatum, frontal cortex and bone (cervical spine). The standardized uptake value (SUV) of each target was obtained from the last three frames of the dynamic study (90–120 min after injection) and calculated in the static images using the following formula: SUV = decay corrected tissue activity concentration (Bq/ml)/injected dose (Bq) × body weight (g).

Statistical Analysis

Results were presented as mean ± 1 SD. Differences among the groups were tested by Mann–Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with SPSS 17.0. Statistical significance was established at the level of 95%.

Results

Changes in Vital Signs According to Animal Condition During Uptake Period

When animals were kept under anesthesia for 90 min at room temperature (group 3), the rectal temperature dropped to 26.3°C ± 0.8°C, and the heart rate dropped to 278.8 ± 23.4 beat/min. This dramatic change of vital signs was prevented when mice were kept on a warming pad (group 1, 36.7°C ± 0.5°C, 305.8 ± 219.2 beat/min) or went without anesthesia (group 2, 36.6°C ± 0.6°C, 389.8 ± 56.9 beat/min).

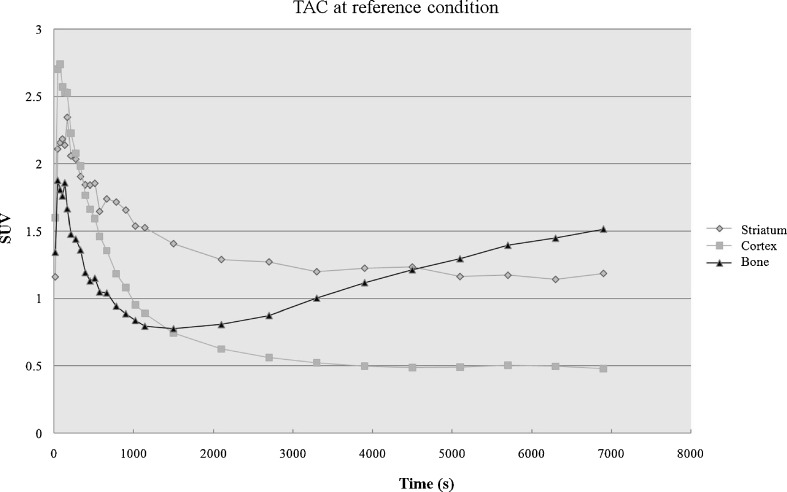

Influence of Anesthesia and Warming

Uptakes in the striatum, cortex, and bone were significantly different among groups (P < 0.05). The lowest striatal specific to cortical non-specific uptake ratio and the highest bone to striatal uptake ratio were seen in group 2. The lowest bone to striatal uptake ratio was seen in group 3, with no significant difference in the striatal specific to cortical non-specific uptake ratio compared to the reference condition. Under all experimental conditions including the reference condition, striatal and cortical activity tended to form a plateau after rapid uptake and washout, but the activity of the bone tended to increase gradually (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Time activity curve of the striatum, cortex, and bone uptake at reference condition (anesthesia with warming). SUV of the striatum and cortex show plateau after rapid uptake and washout, but SUV of the bone tended to increase gradually after rapid uptake and washout

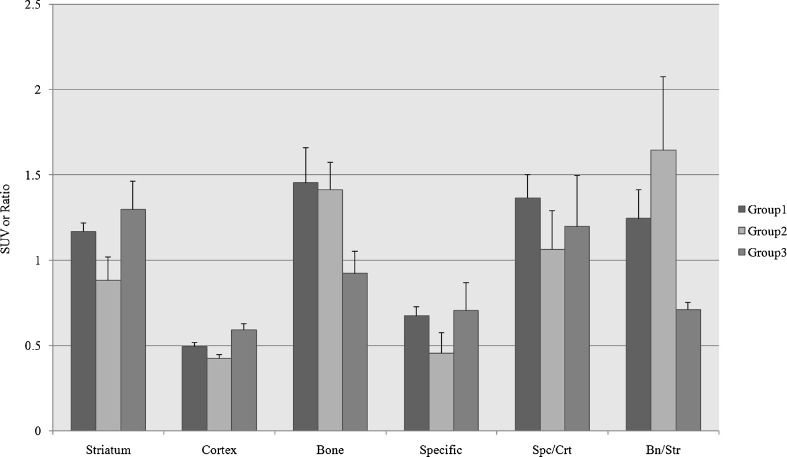

Figure 3 shows typical examples of PET scans in groups 1–3 acquired under the various conditions. The results of the quantitative data are summarized in Fig. 4. Group 2 (no anesthesia without warming) showed reduced striatal and cortical uptakes at 90 min after injection (P < 0.05), but no significant change in the bone uptake (P = 0.564) when compared to the reference condition. Group 3 (anesthesia without warming) showed markedly reduced bone uptake (P < 0.05), with increased cortical uptake (P < 0.05) and an increased tendency in striatal uptake (P = 0.248), even though statistically insignificant.

Fig. 3.

PET images of each condition at post-injection 90 min (left top: coronal, right top: sagittal, left bottom: axial, right bottom: MIP image). (a) PET images obtained under anesthesia with warming, which is the reference condition, shows faint striatal uptake (arrowhead) and strong bone uptake (arrow). (b) In a condition of neither anesthesia nor warming, PET image shows faint uptake in the striatum (arrowheads) and prominent uptake in the bone (arrow). (c) PET image acquired under anesthesia without warming shows increased striatal uptake (arrowhead) but reduced bone uptake (arrow), compared to the reference condition

Fig. 4.

SUV or SUV ratios of target organs in each group. Compared to group 1 (anesthesia with warming, reference), group 2 (no anesthesia or warming) shows reduced striatal and cortical uptakes, and no significant change in the bone uptake. Group 3 (anesthesia without warming) shows markedly reduced bone uptake with slightly increased striatal and cortical uptakes compared to the reference condition. (Specific: striatal specific activity; Spc/Crt: striatal specific activity/cortical non-specific activity; Bn/Str: bone activity/striatal activity)

Influence of Fluvoxamine Pretreatment

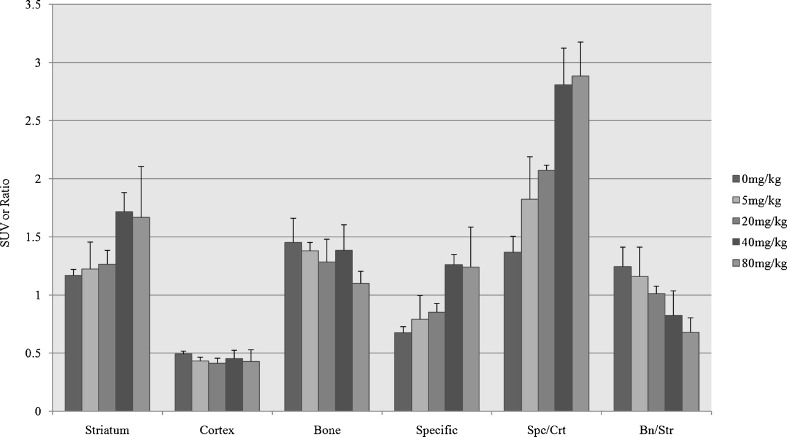

The results of the quantitative data are summarized in Fig. 5. A significant increase of striatal uptake was shown when the dose of fluvoxamine reached 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg (P < 0.05). No significant change of cortical uptake (P = 0.311) was seen. Bone uptake was reduced gradually as the dose of fluvoxamine increased, although this finding was not statistically significant (P = 0.220). There was a gradual increase in the striatal specific to cortical non-specific activity ratio, but a gradual decrease in the bone to striatal uptake ratio (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

SUV or SUV ratios of target organs with escalating dose (0, 5, 20, 40, 80 mg/kg) of fluvoxamine. Serially increased striatal uptake, especially at the dose of 40 mg/kg, without significant changes in the cortical uptake can be seen along with gradually reduced bone uptake as the fluvoxamine dose increases. There also was an increase in the striatal specific to cortical non-specific activity ratio (Spc/Crt), whereas the bone to striatal uptake ratio (Bn/Str) decreased. (Specific: striatal specific activity; Spc/Crt: striatal specific activity/cortical non-specific activity; Bn/Str: bone activity/striatal activity)

Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of anesthesia and temperature of small animals on the results of [18F]FP-CIT PET imaging study. Fluvoxamine, an anti-depressant SSRI frequently used in Parkinson's disease, was also explored to see its effect on the results of [18F]FP-CIT PET. The chief finding of this study was that bone uptake was markedly decreased along with a slight increase in striatal and cortical uptake when the mice were anesthetized without any warming. Without anesthesia or warming, there was a significant decrease in striatal and cortical uptake without any significant change in bone uptake. When the dose of fluvoxamine was raised, it induced a significant increase in striatal uptake, no change in cortical uptake, and a decrease in bone uptake in relation to the dose.

Under anesthesia without any warming, all the mice developed hypothermia. The zone of thermoneutrality in mice lies between 30°C and 34°C. In this range of temperature, the body temperature is controlled by heat convection, and no active processes are necessary for maintenance. At room temperature, mice need to generate heat by the activation of brown adipose tissue and muscle activities to maintain a stable body temperature. Accordingly, basal metabolic rates have been shown to be two times higher at room temperature than at the zone of thermoneutrality [25]. Like most chemical reactions, the rate of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction decreases as the temperature falls. A 10 °C fall in temperature will reduce the activity of most enzymes by 50 to 100%. Variations in temperature as small as 1 or 2° may induce changes of 10 to 20% in the results. Thus, it is inferred that decreased enzyme activity in the whole body due to hypothermia resulted in the reduced production of the metabolite ([18F]fluoride), supported by decreased bone uptake and the preserved parent [18F]FP-CIT uptake in the striatum. Therefore, hypothermia under 30°C will improve the image quality and quantitative results of PET, but it is not physiologic and cannot be used in routine procedures because of its potential to cause unstable vital signs and even possible death in small animals during the study.

The striatal uptake and striatal specific to cortical non-specific activity ratio in the alert condition were significantly decreased without any changes in bone uptake, which suggest inversely that anesthesia per se increases the striatal uptake and striatal specific to cortical non-specific activity ratio. There is much evidence that isoflurane moves the DAT into the cytoplasm so that it inhibits the binding of the DAT-specific tracers [26–29], which is not concordant with our result. The discordance could be explained by the diversity of the examined tissues (in vitro vs. in vivo studies and Rhesus monkeys vs. rats or mice) or by the different concentrations of isoflurane.

Isoflurane is not only an anesthetic agent that affects neurotransmitter receptors, but is also an inhibitor of CYP2E1, which is a common mediator of drug defluorination in mammals [30], and it may have interactions with the defluorination of [18F]FP-CIT. However, our result showed that there were no significant changes between bone uptakes of anesthetized mice and alert ones, which is different from other studies demonstrating successful inhibitions of defluorination of [18F]FCWAY with the use of CYP2E1 inhibitors such as miconazole and disulfiram [15, 16]. Our results suggest that the inhibition of CYP2E1 by isoflurane may have a weak influence on the defluorination of [18F]FP-CIT. The increased striatal DAT activity and specific to non-specific activity ratio may be explained by the decreased production of metabolites from [18F]FP-CIT as a consequence of a significant decrease of the general biological metabolism, since anesthesia has broad effects on the central nervous system and the cardiovascular system [8]. Pretreatment with fluvoxamine induced a significant increase in the striatal uptake and striatal specific to cortical non-specific activity ratio, while causing a gradual decrease in bone uptake. This finding suggests that fluvoxamine may inhibit the defluorination of [18F]FP-CIT. The rate limiting step of defluorination in [18F]FP-CIT is N-dealkylation, because [18F]FP- is rapidly defluorinated to [18F]fluoride by beta-elimination [31]. Because CYP3A4, which is inhibited by fluvoxamine [32], is involved in the N-dealkylation step [33, 34], fluvoxamine may decrease the defluorination of [18F]FP-CIT. The increase in striatal uptake was probably due to the rather preserved amount of the unmetabolized parent [18F]FP-CIT delivered to specific sites when compared to untreated group. The increased specific to non-specific uptake ratio may be attributed to the following explanations. One explanation is that the cortical DAT density may be too low to make a significant difference in the cortical uptake despite the escalation of fluvoxamine doses. Another explanation is that the increased cortical DAT binding of [18F]FP-CIT may be attenuated by the inhibition of cortical SERT binding because of the SSRI effect of fluvoxamine.

The limitations of this study are the rather small number of experimented animals and the usage of normal mice instead of parkinsonism models. Also, further in vivo and in vitro radiometabolite studies should be done in the future.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that anesthesia, body temperature, and pretreatment with fluvoxamine affect the result of [18F]FP-CIT PET study in mice by altering the striatal and bone uptakes.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant (07–405) from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Seoul, Korea

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jones T. The imaging science of positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 1996;23(7):807–813. doi: 10.1007/BF00843711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones T. The role of positron emission tomography within the spectrum of medical imaging. Eur J Nucl Med. 1996;23(2):207–211. doi: 10.1007/BF01731847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatziioannou AF. Molecular imaging of small animals with dedicated PET tomographs. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29(1):98–114. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tornai MP, Jaszczak RJ, Turkington TG, Coleman RE. Small-animal PET: advent of a new era of PET research. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(7):1176–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budinger TF, Benaron DA, Koretsky AP. Imaging transgenic animals. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:611–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherry SR, Gambhir SS. Use of positron emission tomography in animal research. ILAR J. 2001;42(3):219–232. doi: 10.1093/ilar.42.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green MV, Seidel J, Vaquero JJ, Jagoda E, Lee I, Eckelman WC. High resolution PET, SPECT and projection imaging in small animals. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2001;25(2):79–86. doi: 10.1016/S0895-6111(00)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao S, Verkman AS. Analysis of organ physiology in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279(1):C1–C18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleiber M. The fire of life: an introduction to animal energetics. Huntington, NY: R.E. Krieger; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Booij J, Tissingh G, Winogrodzka A, van Royen EA. Imaging of the dopaminergic neurotransmission system using single-photon emission tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with parkinsonism. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26(2):171–182. doi: 10.1007/s002590050374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaly T, Dhawan V, Kazumata K, Antonini A, Margouleff C, Dahl JR, et al. Radiosynthesis of [18F] N-3-fluoropropyl-2-beta-carbomethoxy-3-beta-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane and the first human study with positron emission tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23(8):999–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8051(96)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundkvist C, Halldin C, Ginovart N, Swahn CG, Farde L. [18F] beta-CIT-FP is superior to [11C] beta-CIT-FP for quantitation of the dopamine transporter. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24(7):621–627. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8051(97)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pike VW. PET radiotracers: crossing the blood–brain barrier and surviving metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(8):431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giron MC, Portolan S, Bin A, Mazzi U, Cutler CS. Cytochrome P450 and radiopharmaceutical metabolism. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52(3):254–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipre DN, Zoghbi SS, Liow JS, Green MV, Seidel J, Ichise M, et al. PET imaging of brain 5-HT1A receptors in rat in vivo with 18F-FCWAY and improvement by successful inhibition of radioligand defluorination with miconazole. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(2):345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryu YH, Liow JS, Zoghbi S, Fujita M, Collins J, Tipre D, et al. Disulfiram inhibits defluorination of (18)F-FCWAY, reduces bone radioactivity, and enhances visualization of radioligand binding to serotonin 5-HT1A receptors in human brain. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(7):1154–1161. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.039933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matusch A, Meyer PT, Bier D, Holschbach MH, Woitalla D, Elmenhorst D, et al. Metabolism of the A1 adenosine receptor PET ligand [18 F]CPFPX by CYP1A2: implications for bolus/infusion PET studies. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33(7):891–898. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bier D, Holschbach MH, Wutz W, Olsson RA, Coenen HH. Metabolism of the A(1)1 adenosine receptor positron emission tomography ligand [18 F]8-cyclopentyl-3-(3-fluoropropyl)-1-propylxanthine ([18 F]CPFPX) in rodents and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(4):570–576. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen KG, Poulsen HE, Doehmer J, Loft S. Kinetics and inhibition by fluvoxamine of phenacetin O-deethylation in V79 cells expressing human CYP1A2. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;76(4):286–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumann P. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31(6):444–469. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVane CL, Gill HS. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine: applications to dosage regimen design. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(Suppl 5):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sihver W, Drewes B, Schulze A, Olsson RA, Coenen HH. Evaluation of novel tropane analogues in comparison with the binding characteristics of [18 F]FP-CIT and [131I]beta-CIT. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34(2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SJ, Oh SJ, Chi DY, Kang SH, Kil HS, Kim JS, et al. One-step high-radiochemical-yield synthesis of [18 F]FP-CIT using a protic solvent system. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34(4):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JS, Lee JS, Im KC, Kim SJ, Kim SY, Lee DS, et al. Performance measurement of the microPET focus 120 scanner. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(9):1527–1535. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon CJ. Temperature regulation in laboratory rodents. Cambridge England ; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 1993.

- 26.Eckenhoff RG, Fagan D. Inhalation anaesthetic competition at high-affinity cocaine binding sites in rat brain synaptosomes. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73(6):820–825. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.6.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodman MM, Kilts CD, Keil R, Shi B, Martarello L, Xing D, et al. 18 F-labeled FECNT: a selective radioligand for PET imaging of brain dopamine transporters. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8051(99)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsukada H, Nishiyama S, Kakiuchi T, Ohba H, Sato K, Harada N, et al. Isoflurane anesthesia enhances the inhibitory effects of cocaine and GBR12909 on dopamine transporter: PET studies in combination with microdialysis in the monkey brain. Brain Res. 1999;849(1–2):85–96. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Votaw J, Byas-Smith M, Hua J, Voll R, Martarello L, Levey AI, et al. Interaction of isoflurane with the dopamine transporter. Anesthesiology. 2003;98(2):404–411. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200302000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kharasch ED, Thummel KE. Identification of cytochrome P450 2E1 as the predominant enzyme catalyzing human liver microsomal defluorination of sevoflurane, isoflurane, and methoxyflurane. Anesthesiology. 1993;79(4):795–807. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199310000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welch MJ, Katzenellenbogen JA, Mathias CJ, Brodack JW, Carlson KE, Chi DY, et al. N-(3-[18 F]fluoropropyl)-spiperone: the preferred 18 F labeled spiperone analog for positron emission tomographic studies of the dopamine receptor. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1988;15(1):83–97. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(88)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bondy B, Spellmann I. Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotics: useful for the clinician? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(2):126–130. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f69f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi K, Yamamoto T, Chiba K, Tani M, Shimada N, Ishizaki T, et al. Human buprenorphine N-dealkylation is catalyzed by cytochrome P450 3A4. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26(8):818–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tateishi T, Krivoruk Y, Ueng YF, Wood AJ, Guengerich FP, Wood M. Identification of human liver cytochrome P-450 3A4 as the enzyme responsible for fentanyl and sufentanil N-dealkylation. Anesth Analg. 1996;82(1):167–172. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199601000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]