Abstract

Although sunitinib shows a high response rate in patients with untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), quite a few patients show no therapeutic effect. Therefore, it is crucial to distinguish the patients who respond to sunitinib from those who do not as early as possible after the administration of the therapy. We herein report a case of mRCC in which 11C-acetate (AC) positron emission tomography (PET) showed an early therapeutic effect of sunitinib treatment 4 weeks after its administration.

Keywords: 11C-acetate, Positron emission tomography, Therapeutic effect, Renal cell carcinoma, Sunitinib

Introduction

Although sunitinib shows a high response rate in patients with untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), quite a few patients show no therapeutic effect. Therefore, it is crucial to distinguish the patients who respond to sunitinib from those who do not as early as possible after the administration of sunitinib therapy. We herein report a case of mRCC in which 11C-acetate (AC) positron emission tomography (PET) showed an early therapeutic effect of sunitinib 4 weeks after its administration.

Case Report

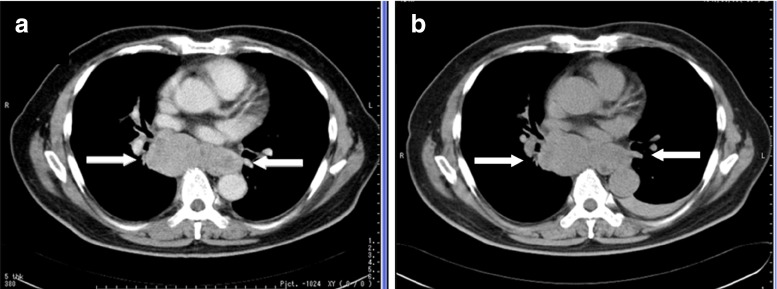

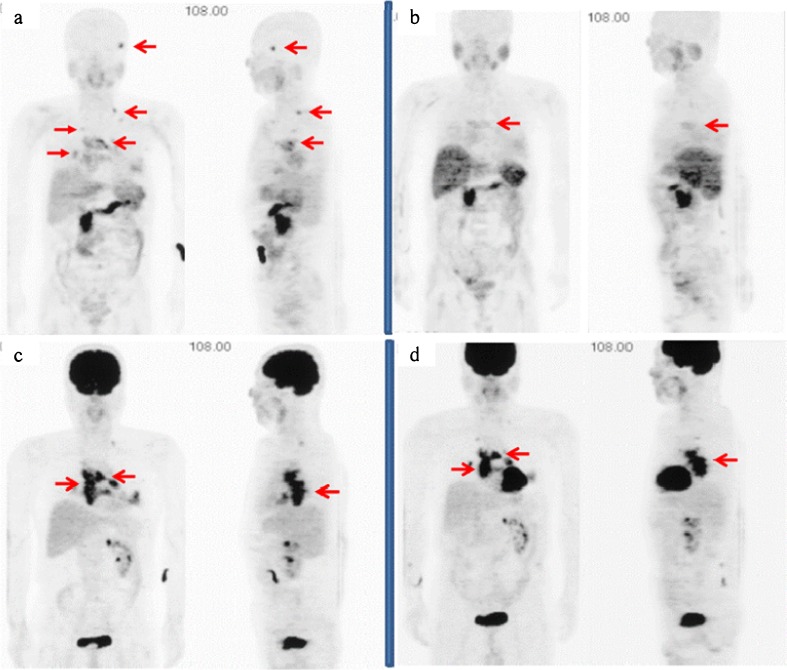

A 58-year-old man underwent a right laparoscopic nephrectomy for a T1bN0M0 renal tumor in March 2006, and the tumor was histologically confirmed to be a pT1b grade-2 clear-cell carcinoma. He received interferon alfa (6 M units × 3/week) for 6 months after the surgery as adjuvant therapy; however, the tumor recurred bilaterally at the lungs, left adrenal gland and mediastinal lymph nodes (LNs). Meanwhile, he exhibited a cough and hoarseness, which were caused by recurrent nerve paralysis due to the mediastinal LN mass (arrows in Fig. 1a). CT also showed a left adrenal mass that was considered to be a new metastatic lesion. He underwent 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) PET and AC PET for further evaluation of recurrent cancer lesions. The PET imaging was approved by the Internal Review Board of our institute. This patient gave written informed consent for having AC and FDG PET imaging performed. AC PET delineated an osseous lesion at his left temporal bone as well as the lung and LN (arrows in Fig. 2a), which was confirmed as osseous metastasis by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This osseous lesion was not recognized by FDG PET (Fig. 2c). The patient received oral sunitinib (Sutent; Pfizer Inc., New York) at 50 mg in a 4-weeks-on/2-weeks-off regimen from September 2008. After the first cycle of sunitinib therapy, all the metastatic cancer lesions were evaluated. The longitudinal diameter of temporal bone lesions detected by MRI decreased from 14 mm prior to therapy to 11 mm afterward. The rest of the lesions detected by CT stayed the same size (arrows in Fig. 1b). FDG PET demonstrated almost equal tracer uptake for the mediastinal LN by visual inspection (Fig. 2d). On the other hand, AC PET showed the disappearance of tracer uptake for the temporal bone and decreased tracer uptake for the mediastinal LN after the first cycle of sunitinib (Fig. 2b). After the second cycle of sunitinib therapy, the sizes of the mediastinal LNs had not changed; however, the density of the central part of the tumor on CT decreased, which suggests a potential for tumor necrosis. The clinical response was judged to be stable disease, and another cycle of sunitinib therapy was performed. After the third cycle of the therapy, all the lesions detected by CT and MRI increased in size. The patient was judged to have disease progression, and sunitinib therapy was terminated.

Fig. 1.

a CT showed a mediastinal lymph node mass. b All lesions stayed the same size after the first cycle of sunitinib

Fig. 2.

a AC PET delineated an osseous lesion at the left temporal bone as well as the lung and lymph nodes. b AC PET showed the disappearance of tracer uptake for the left temporal bone and decreased tracer uptake for the mediastinal lymph nodes after the first cycle of sunitinib. c This osseous lesion was not recognized by FDG PET. d FDG PET demonstrated almost equal tracer uptake for the mediastinal lymph nodes by visual inspection

Discussion

Sunitinib is an oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which has shown its efficacy as a second-line therapy for patients with cytokine-refractory mRCC [1, 2]. Even though progression-free survival was longer in patients with mRCC who received sunitinib than in those receiving interferon alfa, the response rate with sunitinib in patients with mRCC was reported to be 31% for partial response and 48% for stable disease in the phase III trial [2]. Therefore, it is crucial to distinguish the patients who respond to sunitinib from those who do not as early as possible after the administration of sunitinib therapy. FDG PET has been attempted in the evaluation of tumor response to molecular targeting therapy including sunitinib [3, 4]. However, FDG PET has some limitations in evaluating the early effects of cancer therapy, such as its high uptake in tumors early after therapy and its relatively low accumulation in RCC tumor tissue [5–7]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that PET with AC, which is presumed to be an important probe of the anabolic pathway of metabolism in cancer tissue, shows marked uptake in renal cell carcinoma [8–10]. In our case, the longitudinal diameter of temporal bone lesions detected by MRI decreased from 14 mm prior to therapy to 11 mm, and the rest of the lesions detected by CT showed no change in size after the first cycle of sunitinib therapy. FDG PET demonstrated almost equal tracer uptake for mediastinal LN according to visual inspection, whereas AC PET showed the disappearance of tracer uptake for the left temporal bone and decreased tracer uptake for mediastinal LN after the first cycle of sunitinib. This decreased uptake of AC is considered to be due to the therapeutic effect of sunitinib, because the size of temporal bone lesions decreased after the first cycle of the therapy. Although there was no histological confirmation of metastatic renal cancer for the lesions evaluated by PET, they were considered to be recurrent cancer diseases according to the patient’s clinical course of renal cell carcinoma. There is a case report of a patient with mRCC who received sunitinib therapy and whose therapy response was assessed by AC PET [11]. The patient with mRCC was treated with sunitinib, then AC and FDG PET were performed before and 2 weeks after initiation of sunitinib therapy. Two weeks after sunitinib administration, AC PET showed disappearance of the metabolic uptake in liver recurrence. At the end of the first cycle of therapy, CT showed partial response for the same lesion. This is an interesting report; however, the mRCC they assessed was FDG-negative tumor. The usefulness of FDG PET in evaluating the therapy response of mRCC to sunitinib needs to be assessed, because FDG PET has been reported to be valuable in monitoring tumor therapy as well as in predicting tumor prognosis. In conclusion, we report a patient with mRCC who was treated with sunitinib after failure of cytokine therapy. Our case suggests that AC PET is a possible imaging option for assessing the early therapeutic effect of sunitinib in patients with mRCC.

Acknowledgments

The PET imaging was partially supported by a 21st Century COE Grant (Medical Science) and by a Grant-in Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, Curti BD, George DJ, Hudes GR, et al. Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA. 2006;295:2516–2524. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria SC, Macapinlac HA, Burgess MA, Patel SR, et al. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1753–1759. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prior JO, Montemurro M, Orcurto MV, Michielin O, Luthi F, Benhattar J, et al. Early prediction of response to sunitinib after imatinib failure by 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:439–445. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubota R, Kubota K, Yamada S, Tada M, Ido T, Tamahashi N. Microautoradiographic study for the differentiation of intratumoral macrophages, granulation tissues and cancer cells by the dynamics of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:104–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haberkorn U, Bellemann ME, Brix G, Kamencic H, Morr I, Traut U, et al. Apoptosis and changes in glucose transport early after treatment of Morris hepatoma with gemcitabine. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:418–425. doi: 10.1007/s002590100489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyakita H, Tokunaga M, Onda H, Usui Y, Kinoshita H, Kawamura N, et al. Significance of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) for detection of renal cell carcinoma and immunohistochemical glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) expression in the cancer. Int J Urol. 2002;9:15–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shreve P, Chiao PC, Humes HD, Schwaiger M, Gross MD. Carbon-11-acetate PET imaging in renal disease. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1595–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimoto M, Waki A, Yonekura Y, Sadato N, Murata T, Omata N, et al. Characterization of acetate metabolism in tumor cells in relation to cell proliferation: acetate metabolism in tumor cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28:117–122. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8051(00)00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyama N, Okazawa H, Kusukawa N, Kaneda T, Miwa Y, Akino H, et al. 11C-Acetate PET imaging for renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:422–427. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maleddu AM, Pantaleo MA, Castellucci P, Astorino M, Nanni C, Nannini M, et al. 11C-acetate PET for early prediction of sunitinib response in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Tumori. 2009;95:382–384. doi: 10.1177/030089160909500320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]