Abstract

Hibernoma is a rare benign but metabolically active tumor of brown fat origin, that can have cross-sectional imaging characteristics similar to those of other fat-containing tumors, such as lipomas and liposarcomas, and its presence can lead to false-positive interpretation by exhibiting increased F18-fluorodeoxyglucose (F18-FDG) activity. A 46-year-old woman was diagnosed with dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans underwent F18-FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) for detecting recurrence after excision. F18-FDG PET/CT showed incidental intense uptake in the back in addition to increased F18-FDG uptake at the previous lesion site. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of intense F18-FDG uptake in hibernoma in Korea.

Keywords: Hibernoma, Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberance, PET/CT

Introduction

Hibernomas are rare benign tumors of brown fat which can be distinguished histologically from other fatty tumors such as lipomas and liposarcomas. Hibernomas usually present as a heterogenous low-attenuation mass on computed tomography (CT), and as a T1 and T2 heterogenous mass on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Most hibernomas present as a painless mass and an incidental finding on physical examination or imaging. After resection, the tumors generally do not recur and not known to metastasize [1].

We present the case of a hibernoma that was incidentally detected by F18-fluorodeoxyglucose (F18-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT.

Case Report

A 46-year-old woman, who had undergone surgical removal of a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in the left retromastoid area in March 2011 presented for an evaluation of a recurrent palpable mass and two other back masses that she had noted several months earlier. In October 2011, F18-FDG PET/CT was performed. This revealed relatively mild F18-FDG uptake at the previous lesion site with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 2.75 (Fig. 1a, b). A 2 × 4 × 4.5-cm sized, hypermetabolic mass in the subcutaneous layer of the left back at the level of the 9th to 10th thoracic vertebra with SUVmax of 12.83 in a 1-h image (Fig. 2a–f) and 20.83 in a 2-h image (not shown), respectively. A subsequent contrast-enhanced MRI confirmed the location of the left back mass with heterogenous T1 and T2 hyperintensity (hypointense to adjacent subcutaneous fat) (Fig. 3a, b) and intense enhancement after contrast injection with a linear hyperintensity entering the mass (Fig. 3c, d). The mass was not suppressed on fat-saturation image (Fig. 3e). Ultrasonography demonstrated a 4.5-cm sized echogenic soft tissue mass with increased vascularity in the subcutaneous layer of the left back. The lower one of the two palpable back masses was a typical lipoma, as revealed by ultrasonography but was not demonstrated.

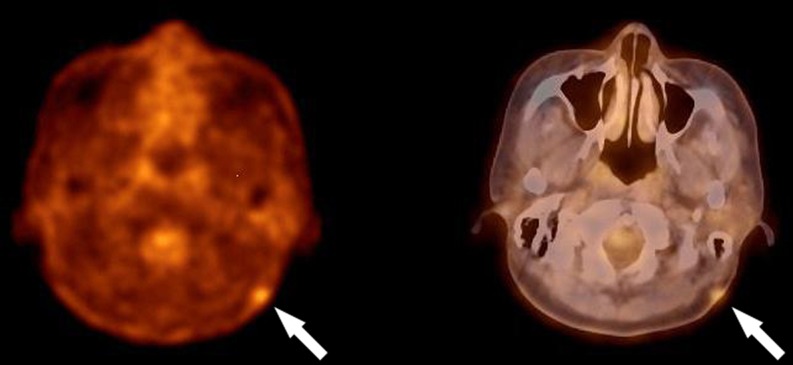

Fig. 1.

Transaxial F18-FDG PET/CT images show a recurrent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in the left retromastoid area with SUVmax of 2.75

Fig. 2.

Transaxial (a, b), sagittal (c, d) and coronal (e, f) F18-FDG PET/CT images show a 2 × 4 × 4.5-cm sized hypermetabolic mass in the subcutaneous layer of the left back at T9-T10 level with SUVmax of 12.83 in 1 h

Fig. 3.

Contrast-enhanced MRI images show the left back mass in subcutaneous layer at T9-T10 level with heterogenous T1 and T2 hyperintensity (hypointense to adjacent subcutaneous fat) (a, b) and intense enhancement with a linear hyperintensity entering the mass (c, d). The mass is not suppressed on fat-saturation image (e)

A marginal tumor resection was performed and the tumor was removed with its capsule. Macroscopically, the mass was gray-tan in color and had a thin capsule and lobulation; invasion into adjacent structures was not seen. The tumor was diagnosed as hibernoma. Microscopic examination showed the tumor to be composed of round or polygonal multivacuolated cells and mature adipose cells, and many small vessels were observed in the tissues. Atypia of nuclei or mitotic activity were not identified (Fig. 4). Left retromastoid and the other back masses were also resected. They were diagnosed as recurrent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and lipoma, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Microscopic view of the tumor shows round or polygonal multivacuolated cells and mature adipose cells, and many small vessels

Discussion

Hibernoma is a rare, slow-growing, benign tumor that was originally described in 1906 by Merkel who named it “pseudolipoma.” Gery was eventually credited with the term “hibernoma” in 1914, when he recognized the tumor’s similarity to brown fat in hibernating animals [1]. Two types of adipose tissue are present in the body; white adipose tissue, which acts as insulation and an energy depot, and brown adipose tissue, which has the ability to generate heat in response to cold exposure (non-shivering thermogenesis) or ingestion of food (diet thermogenesis) [2]. Because it as a major producer of heat and contains a large number of mitochondria, brown fat is highly metabolic, and intense, increased uptake of F18-FDG in areas of brown fat can be seen [3]. Yeung et al. [3] found that 3.7 % of patients had uptake in areas of brown fat, the SUV ranging from 1.9 to 20. Brown fat is found most commonly in the neck, chest near large vessels, axillae, perinephric region, and intercostal spaces and along the spine and paraaortic muscles. It is most prominent in newborns and diminishes with age to virtually disappear in adults. It once was thought that the most common site of hibernoma was residual areas of brown fat. Review of the soft-tissue registry of the Armed Forces Institute, however, showed that the most common location was the thigh, with 30 % of cases occurring there. Various hypotheses are put forward to explain the origin of hibernoma at those sites where brown fat is not present in adults. In these cases, ectopic brown fat, migration of fat precursors, or abnormal differentiation of mesenchymal cells may be responsible. The review also showed a slight male predominance, although hibernomas have been classically described in the literature as being more common among women [4]. Hibernomas occur in the subcutis or rarely, in the muscle [1]. It is estimated that 1.6 % of benign lipomatous tumors have a hibernomatous component [5]. Benign lipomatous lesions are grouped into five major categories: lipoma, variants of lipoma, lipomatous tumor, infiltrating lipoma, and hibernoma [6]. Grossly, hibernomas are well circumscribed, lobulated, and partially encapsulated. The cut surface can vary from yellow to brown and may be mucoid with rare areas of hemorrhage. Unlike classical lipomas, which are composed of univacuolated adiposities with peripheral nuclei, hibernomas contain multi-vacuolated adiposities with central nuclei, rich in mitochondria, and are associated with capillary proliferation and fibrovascular septa. The likelihood of confusing hibernomas with other tumors is minimal [4].

The CT, MRI, ultrasonography, angiography, and F18-FDG PET imaging of hibernomas reflect their histopathology and the relative amount of brown fat and white fat [1, 7–23]. The masses are often heterogenous on MRI and CT with characteristics similar but not identical to those of fat. Hibernomas demonstrate well-defined margins on CT and attenuation between fat and skeletal muscle, depending on the tumor’s lipid content. Multiple vessels are often seen coursing through the mass, with enhancement of soft tissue components after the administration of intravenous contrast medium [1, 8, 9]. MRI also reflects the tumor’s lipid content; some investigators note a correlation between the histological subtype and MRI appearance. One series distinguished between “lipoma-like” and “non-lipoma-like” hibernomas. Lipoma-like hibernomas were isointense to fat on T1-weighted images, predominately homogenous and isointense to fat on T2-weighted images, and displayed no enhancement, or mild homogenous enhancement, or thin, serpentine vessels internally. Non-lipoma-like hibernomas were isointense to mildly hypointense to fat on T2-weighted images, and moderately to markedly inhomogeneous on postcontrast T1-weighted images, showing either diffuse prominent enhancement or intense enhancement in vessels or septa [17]. MR angiography may demonstrate marked vascularity [8]. Saito et al. [19] reported that the signal intensity of a hibernoma was not suppressed on a T2-weighted fat suppression image. The ultrasonographic appearance of hibernoma has been a hyperechoic mass with some hypervascularity and enlarged vessels on Doppler imaging [20, 21]. Only a few reports of conventional angiography of hibernomas are present in the literature. These authors found the tumors to display hypervascularity, with multiple large feeding vessels, but to lack the neovascularity expected in malignant neopla [1, 10, 11]. In our case, a linear hyperintensity entering the enhancing back mass in a contrast-enhanced MRI may be a supplying vessel that was not confirmed by angiography. Hibernomas usually demonstrate intense F18-FDG accumulation [1, 7, 13–18], which has been attributed to the high rate of metabolism of these tumors as precursors of brown fat and should not be regarded as evidence of a malignancy. Hibernomas have been detected incidentally on technetium-99m tetrofosmin myocardial perfusion studies performed in patients with chest pain, appearing as mass-like areas of increased uptake [16, 22].

The differential diagnosis for the CT or MRI findings of hibernoma includes lipoma and liposarcoma. These findings are not reliable for distinguishing well-differentiated liposarcoma from benign fatty tumors. Although definitive differentiation of hibernomas from well-differentiated liposarcomas is often not possible on imaging, well-differentiated liposarcomas tend to have neither the diffuse enhancement and prominent vascularity of some non-lipoma-like hibernomas nor the fine serpentine vascularity in the setting of a homogenously fatty mass characteristic of many lipoma-like hibernomas. Lipomas consistently show a low F18-FDG uptake (SUV < 2.0). F18-FDG PET of lipsarcomas show low to intermediate F18-FDG uptake and SUV values not significantly higher than those of benign lesions [16]. However, a considerable overlap in SUV was observed between many benign and malignant soft tissue lesions. These F18-FDG PET results indicate that SUV may not accurately reflect the malignant potential of soft tissue tumors, but, rather, might implicate cellular components in the lesions. In a series of 57 patients, Suzuki et al. [18] evaluated F18-FDG uptake within fatty tumors. They found that benign tumors such as lipoma exhibited no increased uptake and that liposarcomas exhibited increased uptake, the SUV ranging from 0.1 to 6.0, depending on the grade of the tumor.

The imaging findings of our case were not characteristic of a benign tumor and suggested a worrisome diagnosis of metastasis because of recurrent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans at the previous operation site.

Core needle biopsy has not been recommended in cases of suspected hibernoma due to the tumor’s hypervasculariy [7, 21]. The treatment consists of complete surgical resection and the postoperative prognosis is excellent [1, 4, 14, 23]. In the AFIP series there were no recurrence with an average of 7.7 years of follow-up in 66 patients [4]. Ogilvie et al. [24] reported two cases of recurrent and bleeding hibernomas after intralesional excision

In summary, we reported a case of incidentally detected hypermetabolic hibernoma that could result in a false-positive interpretation by exhibiting intense F18-FDG activity with a SUV similar to that of malignant tumor during a follow-up study of a recurrent dermatofibrosacoma protuberans.

References

- 1.Little BP, Fintlemann FJ, Kenudson MM, Lanuti M, Shepard JO, Digumarthy SR. Intrathoracic hibernoma; a case with multimodality imaging correlation. J Thorac Imaging. 2011;26:W20–W22. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181e35acd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Himms-Hagen J. Thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue as an energy buffer. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1549–1558. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198412133112407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung HW, Grewal RK, Gonen M, Schoder H, Larson S. Patterns of F18-FDG uptake in adipose tissue and muscle: a potential sourse of false-positives for PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1789–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furlong MA, Famburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M. The morphologic spectrum of hibernoma: a clinocopathologic study of 170 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):809–814. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bancroft L, Kransdorf M, Peterson J, O'Connor M. Benign fatty tumors: classification, clinical course, imaging appearance and treatment. Skelet Radiol. 2006;35:719–733. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss S, Goldblum J. Benign lipomatous tumors. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. 4. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 2001. pp. 571–639. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertoghs M, VanSchil P, Rutsaert R. Intrathoracic hibernoma: report of two cases. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:367–370. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson S, Schwab C, Stauffer E, Banic A, Steinbach L. Hibernoma:imaging characteristics of a rare benign soft tissue tumor. Skelet Radiol. 2001;30:590–595. doi: 10.1007/s002560100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colville J, Feigin K, Antoneseu CR, Panic DM. Hibernoma: report emphasizing large lintratumoral vessels and high T1 signal. Skelet Radiol. 2006;35:547–550. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy MD, Caroll JF, Flemming DJ. From the archives of the AFIP: benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. Radiographics. 2004;24:1433–1466. doi: 10.1148/rg.245045120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLane RC, Meyer LC. Axillary hibernoma: review of the literature with report of a case examined angiographically. Radiology. 1978;127:673–679. doi: 10.1148/127.3.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ritchie DA, Aniq H, Davies AM. Hibernoma-correlation of histopathology and magnetic-resonance-imaging features in 10 cases. Skelet Radiol. 2006;35:579–589. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuchiya T, Osanai T, Ishikawa A, Kato N, Watanabe Y, Ogino T. Hibernomas show intense accumulation of FDG positron emission tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:333–336. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200603000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subramaniam RM, Clayton AC, Karantanis D, Collins DA. Hibernoma: 18FDG PET/CT imaging. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(6):569–570. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31805fe2a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CS, Feldstein JT, Caravelli JF, Yeung HW. False-positive findings on 18F-FDG PET/CT: differentiation of hibernoma and malignant fatty tumor on the bases of fluctuationg standardized uptake values. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1091–1096. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterton BE, Mensforth D, Coventry BJ, Cohen P. Hibernoma: intense uptake seen on Tc-99m tetrofosmin and FDG positron emission tomographic scanning. Clin Nucl Med. 2002;27:369–370. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoki J, Endo E, Watanabe H. FDG-PET for evaluating musculoskeletal tumors: a review. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8:435–441. doi: 10.1007/s10776-001-0539-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki R, Watanabe H, Takashi Y. PET evaluation of fatty tumors in the extremity: possibility of using the standardized uptake value(SUV) to differentiate benign tumors from liposarcoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2005;19:661–670. doi: 10.1007/BF02985114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito M, Tsuji Y, Murata H, Kanemitsu K, Makinodan A, Ikeda T, et al. Hibernoma of the right back. Orthopedics. 2007;30(6):495. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20070601-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baskurt E, Padgett DM, Matsumoto JA. Multiple hibernomas in a 1-month-old female infant. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1443–1445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallas KM, Vaughan L, Haghighi P, Resnick D. Hibernoma of the left axilla; a case report and review of MR imaging. Skelet Radiol. 2003;32:290–294. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oller JD, Gomez JD, Kortazar JF. Scapular hibernoma fortuituously discovered on myocardial perfusion imaging through Tc-99m tetrofosmin. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:69–70. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morta ACBS, Tunkel DE, Westra WH, Yousem DM. Imaging findings of a hibernoma of the neck. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1658–1659. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogilvie CM, Torbert JT, Hosalkar HS. Recurrence and bleeding in hibernomas. Clin Orthop. 2005;438:137–145. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000179589.27103.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]