Abstract

Chronic inflammation is a potentially important physiological mechanism linking early life environments and health in adulthood. Elevated concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP)—a key biomarker of inflammation—predict increased cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk in adulthood, but the developmental factors that shape the regulation of inflammation are not known. We investigated birth weight and breastfeeding duration in infancy as predictors of CRP in young adulthood in a large representative cohort study (n = 6951). Birth weight was significantly associated with CRP in young adulthood, with a negative association for birth weights 2.8 kg and higher. Compared with individuals not breastfed, CRP concentrations were 20.1%, 26.7%, 29.6% and 29.8% lower among individuals breastfed for less than three months, three to six months, 6–12 months and greater than 12 months, respectively. In sibling comparison models, higher birth weight was associated with lower CRP for birth weights above 2.5 kg, and breastfeeding greater than or equal to three months was significantly associated with lower CRP. Efforts to promote breastfeeding and improve birth outcomes may have clinically relevant effects on reducing chronic inflammation and lowering risk for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in adulthood.

Keywords: population health, inflammation, developmental origins of health and disease, cardiovascular disease, health disparities

1. Introduction

The association between adverse environments in infancy and poor health in adulthood has been known for almost a century [1,2]. The key exposures, and the intervening mechanisms linking them to long run health outcomes, however, remain opaque. Research on the ‘fetal origins hypothesis’ has focused primarily on birth weight as a proxy for prenatal nutritional conditions and has consistently documented associations with adult cardiovascular and metabolic processes and outcomes [3–5].

Recently, chronic inflammation has become a major focus of epidemiological and clinical research on cardiovascular disease [6,7], as well as community-based research into the mechanisms linking social environments and health [8–11]. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a prototypical acute phase protein produced in response to pro-inflammatory cytokine signals, and it plays important roles in activating complement, promoting phagocytic activity and opsonizing bacteria, fungi and parasites—all activities that are central to innate immune defences [12–14]. However, chronic activation of inflammatory processes has been implicated in multiple aspects of atherosclerosis, including enhanced expression of cell adhesion molecules, leucocyte recruitment into subintimal space, uptake of cholesterol lipoproteins and fatty streak initiation, smooth muscle loss, and growth and destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques [7,15]. The precise pathophysiological role of CRP in these processes is not clear, but CRP is widely used as a sensitive, endpoint marker of systemic inflammation that is consistently associated with elevated risk for incident cardiovascular disease [16], type 2 diabetes [17], late-life disability [18] and all-cause mortality [19,20]. Levels of chronic inflammation are socially patterned in the USA, with significantly higher CRP concentrations in lower socioeconomic and disadvantaged race/ethnic groups [21–25].

The extent to which chronic inflammation in adulthood is influenced by exposures in infancy is not known. A handful of international cohort studies has correlated lower birth weight with higher adult CRP [26–29], suggesting that inflammation may serve as an intervening mechanism linking lower birth weight and elevated chronic disease risk later in life [4,5]. However, as with most observational cohort studies, residual confounding is a substantial concern: family socioeconomic status, for example, is strongly associated with birth outcomes, and may also establish trajectories of risk that predispose children to chronic disease in adulthood, independently of the prenatal environment [30].

Furthermore, correlated aspects of the postnatal environment, often overlooked in studies that focus on birth weight, may have lasting effects on inflammation. Breastfeeding provides nutritional and immunological support to infants following delivery and has sensitive period effects on immune development and metabolic processes related to obesity—two potential avenues of influence on adult CRP production [31,32]. Breastfeeding is of particular interest since current guidelines in the USA and the UK recommend exclusive breastfeeding to six months of age, and continued breastfeeding to at least 1 year [33,34]. Only a small proportion of infants currently meet these recommendations [34,35], with lower uptake for some race/ethnic groups and mothers with lower levels of education [36]. Parallel race- and education-based disparities in birth outcomes further motivate attention to early environments as potential contributors to disparities in health later in life [37,38].

We investigated birth weight and breastfeeding duration in infancy as predictors of CRP in young adulthood, using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). The size, longitudinal scope and national representation of the Add Health cohort provide an exceptional opportunity to investigate the early life determinants of inflammation and their relevance to population health. In addition, the study design enables us to estimate sibling comparison models that account for unmeasured characteristics of early environments that are common to siblings, and that simultaneously affect offspring birth weight, breastfeeding decisions, as well as trajectories of health. Sibling comparison models—a form of fixed-effects modelling—use differences between siblings as the independent and dependent variables to estimate regression model parameters [39]. As a consequence, any characteristics, observable or unobservable, that are shared by siblings are differenced out of the model. A sibling fixed-effects approach is particularly useful for our purposes since it implicitly controls for many of the factors that may bias the estimated impacts of birth weight and breastfeeding on adult CRP. In this way, we are able to address concerns regarding residual confounding, and the primary emphasis on birth weight, that have been raised with respect to prior research on the fetal origins hypothesis [30,40].

2. Material and methods

(a). Participants and study design

Data come from the first and fourth waves of the US National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, a large, nationally representative study of the social, behavioural and biological linkages defining health trajectories from adolescence through to adulthood [41]. The Wave 1 in-home interview was conducted in 1994–1995 with a stratified random sample of 20 745 seventh through to 12th graders attending a nationally representative sample of 80 middle and high schools. Of this initial sample, 17 670 parents were also interviewed at Wave 1. Conducted in 2007–2008, Wave 4 provided both interview and biomarker data on 15 701 of the original study participants when they were 24–32 years old. Procedures for data access and analysis were implemented as approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University, and in agreement with the sensitive data security plan approved by Add Health data managers.

(b). Measurement of C-reactive protein

Prior validation studies in the USA have demonstrated that high-sensitivity CRP concentrations are relatively stable within individuals across time, with levels of variability that are comparable to total cholesterol, thereby supporting the use of a single CRP measure to indicate chronic levels of systemic inflammation [42,43]. We measured CRP in dried blood spot (DBS) samples—drops of capillary whole blood collected on filter paper (Whatman #903) following simple finger stick—that were collected from 94% of participants as part of the Wave 4 in-home interview [44]. DBS sampling has recently been incorporated into several population-based surveys like Add Health, building on its longstanding application in routine neonatal screening programmes [45]. CRP was quantified based on modifications to a high-sensitivity protocol previously validated for use with DBS samples [46]. Results are reported as serum equivalent values, calculated from a conversion factor derived from the analysis of 80 matched serum and DBS samples. Prior validation of assay performance indicates that the DBS CRP method produces results that are comparable to gold standard serum-based clinical methods [46].

(c). Independent variables

Information on participant birth weight and duration of breastfeeding was based on maternal recall in the Wave 1 parental interview. For breastfeeding duration, parents were asked, ‘For how long was [child's name] breastfed?’ and chose from seven categories: less than three months, three to six months, 6–9 months, 9–12 months, 12–24 months, greater than 24 months or never breastfed. Owing to small sample sizes for the categories above six months, for our analyses we consolidated responses of six months or more into ‘6–12 months’ and ‘greater than 12 months’. Breastfeeding duration was entered into regression models as a series of indicator variables, with no breastfeeding serving as the omitted reference group. Birth weight was entered as a continuous variable and a squared term after preliminary analyses suggested a nonlinear association between birth weight and CRP. In addition to these primary independent variables, non-fixed-effects models included a comprehensive set of sociodemographic and contextual variables collected during Wave 1 (e.g. gender, race/ethnicity, parental education) and health behaviour variables at Wave 4 known to influence inflammation (e.g. smoking, oral contraceptive use). Waist circumference at Wave 4 was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm at the superior border of the iliac crest [44].

(d). Data analysis

Complete data were available for n = 10 422 participants. The majority of cases with incomplete data were missing information concerning the key independent variables of breastfeeding duration (missing for n = 2352) and birth weight (missing for n = 2592). Studies measuring CRP as a biomarker of chronic, low-grade inflammation typically remove from the analysis individuals with acute elevations in CRP owing to infection around the time of blood collection since these values do not represent baseline levels of inflammatory activity that are predictive of subsequent risk for chronic disease [7]. For this analysis, we excluded individuals reporting symptoms of infection in the two weeks preceding blood collection (n = 3337), based on the presence of any of the following self-reported symptoms: cold or flu-like symptoms (22.4% of sample), fever (4.3%), night sweats (4.0%), nausea/vomiting/diarrhoea (7.5%) and/or frequent urination (2.7%). High rates of symptoms—particularly cold or flu-like symptoms—may be due in part to reporting bias, but prior to constructing the summary infectious symptoms variable we confirmed that each symptom was associated with significantly elevated concentrations of CRP in our sample. For example, median CRP was 2.81 mg l−1 for individuals reporting cold/flu-like symptoms, in comparison with 1.81 mg l−1 for those not reporting cold/flu symptoms. Pregnant women (n = 363) were also excluded, resulting in a final sample of n = 6951. Analyses were implemented in Stata (v. 12, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) with Add Health longitudinal sampling weights, which adjust for complex sample design, selection and non-response.

Following previous research [27,47], we implemented a stepwise series of models to isolate the independent associations of birth weight and breastfeeding with CRP in young adulthood. First, we estimated bivariate associations between birth weight and log-transformed CRP (base 10), and between breastfeeding and log CRP, using weighted least-squares regression. Preliminary analyses indicated that the association between birth weight and log CRP was approximately linear across the range of birth weights, with the exception of values at the very low end of the birth weight distribution. We therefore included a quadratic term (birth weight2) to account for this nonlinearity. We then included a series of Wave 1 and 4 control variables, representing factors that may confound associations between early environments and adult CRP. In a final model, we added waist circumference at Wave 4 to evaluate central adiposity as a potential mediator of early environment effects on inflammation. Preliminary analyses indicated that patterns of association were similar for males and females, with no evidence for statistically significant interactions between birth weight or breastfeeding duration and CRP.

This series of models was then repeated using sibling fixed effects regression for the subset of full biological siblings in the dataset (n = 698, with 346 sibling groups comprised of 340 pairs and six sibling trios). These models included only those control variables that differed across siblings. All analyses were repeated to evaluate the sensitivity of results to alternative strategies for handling acute elevations in CRP. In particular, we implemented models excluding outlier values for CRP (greater than 25 mg l−1), and models including covariates for infectious symptoms to adjust for acute inflammation, rather than excluding these observations from the analytic sample.

3. Results

Overall, 44.8% of participants were breastfed as infants for some amount of time, with large differences in initiation and duration across race/ethnic and education groups (tables 1 and 2). Mean birth weight in the sample was 3.38 kg (7.45 lbs), with significant differences across race/ethnic and education groups as well (table 2). Median CRP concentration was 2.08 mg l−1 for the entire sample and 1.69 mg l−1 for the analytic sample. The analytic sample excluded participants with infectious symptoms at the time of blood collection, as values associated with acute inflammatory responses do not represent baseline levels of chronic inflammation that are predictive of subsequent disease risk [7].

Table 1.

Composition of the analytic sample. (n = 6951. All estimates use sampling weights.)

| per cent | |

|---|---|

| sex | |

| male | 54.0 |

| female | 46.0 |

| race/ethnicity | |

| latino/a | 11.2 |

| white (non-latino) | 71.9 |

| black (non-latino) | 13.1 |

| asian (non-latino) | 2.5 |

| native american (non-latino) | 0.7 |

| other (non-latino) | 0.7 |

| parent education | |

| less than high school | 13.1 |

| high school diploma/general educational development (GED) | 31.4 |

| some college | 21.3 |

| college degree | 23.2 |

| more than college | 10.9 |

| breastfeeding duration | |

| never | 55.2 |

| less than three months | 14.0 |

| three to six months | 10.4 |

| 6–12 months | 13.4 |

| greater than 12 months | 7.1 |

| birth control pill | 14.8 |

| daily smoker | 24.9 |

| first born child | 63.2 |

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between demographic factors and birth weight, and duration of breastfeeding (n = 6951).

| birth weight (kg) |

never breastfed |

breastfed for less than three months |

breastfed for greater than three months |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (s.e.) | p-valuea | % (s.e.) | p-valueb | % (s.e.) | p-valueb | % (s.e.) | p-valueb | |

| sex | ||||||||

| female | 3.31 (0.02) | 56.4 (1.8) | 13.0 (0.9) | 30.6 (1.6) | ||||

| male | 3.43 (0.01) | 54.1 (1.7) | 14.9 (1.0) | 30.9 (1.5) | ||||

| difference | <0.001 | 0.145 | 0.105 | 0.828 | ||||

| race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| latino/a | 3.38 (0.04) | 47.6 (2.7) | 18.2 (2.0) | 34.5 (2.4) | ||||

| white (non-latino) | 3.42 (0.01) | 53.1 (1.8) | 14.4 (0.9) | 32.6 (1.7) | ||||

| black (non-latino) | 3.19 (0.02) | 79.5 (2.2) | 7.8 (1.2) | 12.7 (1.6) | ||||

| asian (non-latino) | 3.15 (0.07) | 30.0 (4.8) | 10.6 (3.2) | 59.6 (5.6) | ||||

| native american (non-latino) | 3.43 (0.14) | 55.7 (10.3) | 17.7 (9.2) | 26.6 (7.6) | ||||

| other (non-latino) | 3.43 (0.11) | 27.1 (8.1) | 38.4 (10.5) | 34.5 (9.0) | ||||

| difference | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| birth order | ||||||||

| first born | 3.36 (0.01) | 55.2 (1.7) | 15.0 (0.9) | 29.8 (1.5) | ||||

| not first born | 3.42 (0.02) | 55.0 (1.8) | 12.5 (1.1) | 32.6 (1.8) | ||||

| difference | 0.010 | 0.845 | 0.068 | 0.082 | ||||

| parent education | ||||||||

| less than high school | 3.31 (0.04) | 70.8 (2.8) | 10.5 (1.5) | 18.7 (2.2) | ||||

| high school diploma/GED | 3.35 (0.02) | 67.7 (1.8) | 11.4 (1.0) | 20.8 (1.4) | ||||

| some college | 3.38 (0.02) | 54.0 (2.1) | 18.2 (1.5) | 27.8 (1.7) | ||||

| college degree | 3.41 (0.02) | 43.4 (2.0) | 15.5 (1.4) | 41.1 (2.0) | ||||

| more than college | 3.44 (0.02) | 27.3 (2.5) | 14.7 (1.5) | 58.0 (2.8) | ||||

| difference | 0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| total | 3.38 | 55.2 | 14.1 | 30.8 | ||||

aBirth weight p-values reflect t-tests for sex and birth order, ANOVA for race/ethnicity and parent education.

bBreastfeeding p-values reflect χ2-tests.

Table 3 presents results from the weighted least-squares regression models and documents significant differences in adult CRP associated with race/ethnicity and parental education (model 1). In particular, higher CRP concentrations among African Americans, and among individuals from households with less educated parents, are consistent with prior research in the USA [48]. There is a significant, but nonlinear, association between birth weight and CRP in adulthood (model 2). This association strengthens when breastfeeding duration (model 4), other control variables (model 5) and waist circumference (model 6) are considered. For the small proportion of birth weights of less than 2.8 kg (12.9%), the association between birth weight and CRP is positive, while above 2.8 kg the association is negative. Predicted CRP in adulthood for individuals born at 2.8 kg is 2.60 mg l−1 (95% confidence interval (CI): 2.41, 2.80), compared with 2.36 mg l−1 (95% CI: 2.20, 2.52) for individuals born 1 kg heavier, a 9.2% decrease in adult CRP.

Table 3.

Coefficients and standard errors from weighted least-squares regression models predicting log CRP, n = 6951. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, +p < 0.10.)

| model 1 |

model 2 |

model 3 |

model 4 |

model 5 |

model 6 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | |

| birth weight (kg) | 0.180+ | (0.094) | 0.218* | (0.093) | 0.195* | (0.089) | 0.224** | (0.079) | ||||

| birth weight2 | −0.032* | (0.014) | −0.036* | (0.014) | −0.030* | (0.013) | −0.040** | (0.012) | ||||

| never breastfed | reference | reference | reference | reference | ||||||||

| breastfed less than three months | −0.084** | (0.027) | −0.083** | (0.027) | −0.065* | (0.028) | −0.041 | (0.026) | ||||

| three to six months | −0.125** | (0.028) | −0.126** | (0.028) | −0.104** | (0.029) | −0.051* | (0.024) | ||||

| 6–12 months | −0.166** | (0.031) | −0.165** | (0.031) | −0.126** | (0.031) | −0.074** | (0.024) | ||||

| greater than 12 months | −0.149** | (0.041) | −0.147** | (0.040) | −0.120** | (0.038) | −0.068* | (0.033) | ||||

| male | −0.206** | (0.017) | −0.162** | (0.020) | −0.191** | (0.016) | ||||||

| white (non-latino) | reference | reference | reference | |||||||||

| latino/a | 0.048 | (0.029) | 0.066* | (0.030) | 0.050* | (0.025) | ||||||

| black (non-latino) | 0.060* | (0.027) | 0.048+ | (0.028) | 0.039 | (0.024) | ||||||

| asian (non-latino) | −0.228** | (0.041) | −0.196** | (0.042) | −0.114** | (0.031) | ||||||

| native american (non-latino) | 0.206** | (0.154) | 0.198 | (0.160) | 0.026 | (0.094) | ||||||

| other (non-latino) | −0.034 | (0.092) | −0.029 | (0.091) | 0.001 | (0.075) | ||||||

| parent's education: less than high school | reference | reference | reference | |||||||||

| parent's education: high school | 0.009 | (0.029) | 0.006 | (0.029) | 0.014 | (0.025) | ||||||

| parent's education: some college | −0.020 | (0.033) | −0.015 | (0.034) | 0.008 | (0.029) | ||||||

| parent's education: college graduate | −0.081* | (0.033) | −0.062+ | (0.035) | −0.009 | (0.026) | ||||||

| parent's education: more than college | −0.119** | (0.036) | −0.079* | (0.037) | −0.029 | (0.031) | ||||||

| first born child | 0.008 | (0.020) | 0.002 | (0.016) | ||||||||

| daily smoker | 0.032 | (0.022) | 0.057** | (0.019) | ||||||||

| birth control pill | 0.134** | (0.026) | 0.230** | (0.022) | ||||||||

| waist circumference (cm) | 0.016** | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| r2 | 0.051 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.066 | 0.297 | ||||||

In unadjusted models, and after accounting for birth weight (models 3 and 4), breastfeeding duration is a significant predictor of lower CRP in young adulthood. The pattern of coefficients suggests a threshold association between breastfeeding duration and CRP, with substantially lower concentrations of CRP for individuals breastfed for three months or longer. Associations were attenuated, but remained statistically significant, with the addition of baseline covariates representing potentially confounding influences (model 5). When waist circumference in adulthood was added to the model, associations between breastfeeding duration and CRP were attenuated further but remained statistically significant (model 6). The significant associations between CRP and race/ethnicity and parental education reported in model 1 are substantially reduced in magnitude when birth weight and breastfeeding duration are considered in the models.

Waist circumference is a well-established predictor of chronic inflammation [49], and prior research has documented protective effects of breastfeeding in preventing overweight and obesity in adulthood [50]. These associations suggest that waist circumference represents a plausible mediator of the effects of breastfeeding on inflammation. Accordingly, we conducted Sobel–Goodman tests of statistical mediation [51]. Results indicate that adult waist circumference accounted for 37.3% (p = 0.07), 50.8% (p < 0.001), 41.2% (p < 0.001), and 43.6% (p < 0.01) of the association between adult CRP and breastfeeding durations of less than three months, three to six months, 6–12 months and greater than 12 months, respectively, relative to non-breastfed individuals.

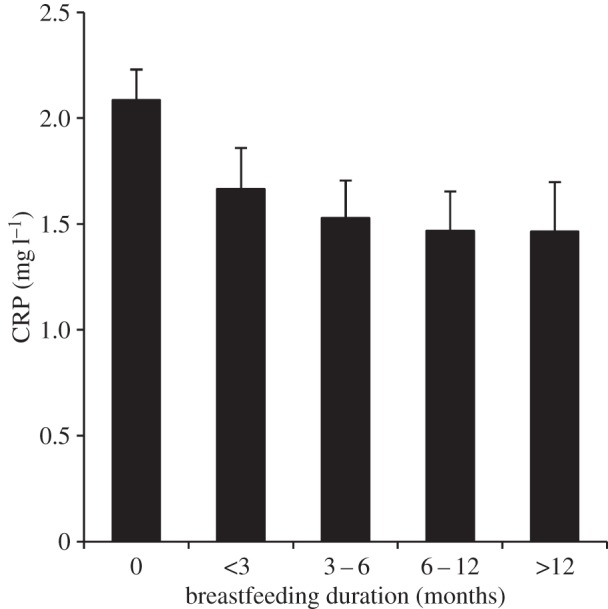

Figure 1 presents the association between breastfeeding duration and CRP, without adjustment for waist circumference. Compared with individuals not breastfed, CRP concentrations were 20.1%, 26.7%, 29.6% and 29.8% lower among individuals breastfed for less than three months, three to six months, 6–12 months and greater than 12 months, respectively.

Figure 1.

Predicted CRP values by breastfeeding duration. Note: values are based on coefficients from table 3, model 5 (n = 6951). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 4 presents results from fixed-effects sibling models. As might be expected from the smaller sample size and more limited variation in dependent and independent variables, standard errors are considerably larger than in table 3. Differences in birth weight across siblings significantly predicted differences in adult CRP concentration, with a nonlinear pattern of association similar to results from the full sample. The quadratic peak in the sibling models was approximately 2.5 kg, with a positive association between birth weight and CRP below this threshold, and a negative association above. Based on the sibling comparisons, predicted CRP in adulthood for individuals born at 2.5 kg is 2.83 mg l−1 (95% CI: 2.24, 3.42), compared with 2.15 mg l−1 (95% CI: 1.67, 2.62) for individuals born 1 kg heavier, a 24.0% difference.

Table 4.

Coefficients and standard errors from fixed-effects sibling comparison models predicting log CRP, n = 698. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, +p < 0.10.)

| model 1 |

model 2 |

model 3 |

model 4 |

model 5 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | |

| birth weight (kg) | 0.619+ | (0.343) | 0.675* | (0.062) | 0.740* | (0.340) | 0.649* | (0.313) | ||

| birth weight2 | −0.130* | (0.054) | −0.138** | (0.054) | −0.143** | (0.053) | −0.128** | (0.049) | ||

| breastfed ≥3 months (versus <3 months) | −0.222+ | (0.134) | −0.232+ | (0.132) | −0.271* | (0.130) | −0.215+ | (0.120) | ||

| male | −0.200** | (0.063) | −0.247** | (0.059) | ||||||

| birth control pill | 0.064 | (0.082) | 0.076 | (0.076) | ||||||

| daily smoker | −0.117 | (0.072) | −0.092 | (0.067) | ||||||

| first born child | −0.013 | (0.054) | −0.019 | (0.050) | ||||||

| waist circumference (cm) | 0.013** | (0.002) | ||||||||

| R2, within sibling groups | 0.045 | 0.008 | 0.053 | 0.099 | 0.235 | |||||

| R2, between sibling groups | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.0004 | 0.006 | 0.264 | |||||

| R2, overall | 0.0001 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.257 | |||||

Owing to the more limited variation in breastfeeding duration between siblings than in the full population, we chose three months as a single cut-point based on results in table 3 (25 sibling pairs and one sibling trio contained siblings on both sides of the three month breastfeeding cut-point, for a subsample of n = 53 ‘discordantly fed’ participants). The estimated magnitude of the association between breastfeeding duration and CRP is larger than in table 3, with a statistically significant association between longer breastfeeding and lower adult CRP after covariate adjustment (model 4). According to this model, predicted CRP in adulthood is 2.25 mg l−1 (95% CI: 1.79, 2.72) in siblings breastfed less than three months, compared with 1.21 mg l−1 (95% CI: 0.70, 1.71) for those breastfed three months or longer, a 46.2% difference in adult CRP concentrations.

Finally, we evaluated the robustness of these results to alternative strategies for controlling for infectious symptoms around the time of blood collection. Specifically, we repeated our analyses using an indicator variable to control for the presence of infectious symptoms, rather than excluding individuals with infectious symptoms from the analytic sample. We also considered a series of models that excluded individuals with CRP > 25 mg l−1 (n = 295) to eliminate potential influence of outlier values. Results from least-squares regression models were very similar for breastfeeding duration, both in terms of magnitude and significance of the associations with CRP. Birth weight coefficients were also similar, but attenuated in magnitude. Results from sibling comparison models were similar, although the coefficients for the association between CRP and birth weight and breastfeeding greater than three months were substantially smaller in magnitude in the fully adjusted model.

4. Discussion

Clinicians, researchers and policy-makers increasingly emphasize the importance of prenatal and early postnatal environments in influencing physiological function and health over the life course [4,52]. In this analysis, we document large disparities in birth weight and rates of breastfeeding associated with race/ethnicity and education level. We present evidence that lower birth weight and shorter durations of breastfeeding both predict elevated concentrations of CRP in young adulthood, indicating increased risk for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases that are major health burdens in the USA and the UK. Clinical trials have demonstrated that statin therapy reduces CRP in healthy adults by 14.8–17.4% [53–55]. Our results suggest that the effects of breastfeeding on adult CRP are comparable, or larger, in magnitude.

Advantages of our study include the use of a large, nationally representative sample and the application of sibling fixed-effects models that account for hard-to-measure attributes that may otherwise confound associations between early environments and adult health. A limitation of our study is the application of maternal recall to collect information on birth weight and breastfeeding duration. However, prior validation studies indicate that maternal reports of birth weight correlate highly with birth records, and that breastfeeding initiation and duration are also reported with high validity and reliability [56,57]. In addition, similar to other epidemiological studies of inflammation [17,58,59], the Add Health study uses a single CRP measure to assess baseline levels of inflammation, which makes it more difficult to differentiate acute from chronic, low-grade inflammatory activity. Multiple CRP values would be preferable, but we use infectious symptoms to control for the predominant source of acute activation in young adults.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to document an association between birth weight and CRP in sibling comparison models, which eliminate a wide range of potentially confounding influences on adult CRP and increase our confidence in concluding that aspects of the prenatal environment have effects on the regulation of inflammation that last into adulthood. At birth weights above 2.5–2.8 kg, we find a negative association between birth weight and CRP, consistent with prior studies [26–29,60]. We are not aware of previous research documenting positive associations between CRP and birth weight at the low end of the birth weight distribution, but it is not clear if prior studies adequately considered the possibility of nonlinear associations. Since lower birth weights in the USA are typically associated with shorter gestation, it is possible that pre-term delivery is contributing to this pattern of results. Unfortunately, the Add Health study did not collect information on gestational age, so exploring this issue in greater depth remains for future research. Regardless, a large body of epidemiological research has documented associations between birth weight and risk for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases later in life [4,5], and our results point towards chronic inflammation as a potentially important intervening mechanism.

While the prenatal environment has been the primary focus of research on the fetal origins hypothesis, postnatal feeding decisions may provide additional opportunities for intervention, particularly given low rates of extended breastfeeding in the USA and the UK. Our findings are consistent with prior studies in New Zealand and Scotland [61,62] and are important in demonstrating negative associations between breastfeeding duration and CRP concentration in a large representative sample of adults in the USA. Results from sibling comparison models are particularly compelling in that they control for many characteristics of families—observed or unobservable—that may bias estimates of the impact of breastfeeding on adult CRP. Although the relatively small number of discordant siblings cautions against over-interpretation, it is worth noting that the magnitude of the association between breastfeeding duration and CRP was substantially larger in the sibling comparison models. Consumption of breast milk in infancy may have lasting effects on inflammation by shaping regulatory pathways during sensitive periods of immune development [63,64]. Effects of breastfeeding may also be indirect, through programming of metabolic pathways that reduce the accumulation of body fat and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [49,50].

Lower birth weights and shorter durations of breastfeeding are associated with elevated concentrations of CRP in young adulthood. Efforts to improve birth outcomes, and to increase the initiation and duration of breastfeeding in accordance with current recommendations, may reduce levels of chronic inflammation in adulthood and lower risk for chronic degenerative diseases of ageing. A focus on environments early in development may also help address social disparities in population health outcomes in adulthood, which run parallel to, and perhaps derive in part from, social disparities in birth weight and breastfeeding behaviour [38,65].

Acknowledgements

This project's contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Special acknowledgement is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design.

Data accessibility

Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth).

Funding statement

This project was supported by grant no. R01HD053731 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health. This research was funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. T.W.M. also acknowledges research support as a Fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, program in Child and Brain Development.

References

- 1.Forsdahl A. 1977. Are poor living conditions in childhood and adolescence an important risk factor for arteriosclerotic heart disease? Br. J. Prev. Soc. Med. 31, 91–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kermack WO, McKendrick AG, McKinlay PL. 1934. Death rates in Great Britain and Sweden: some general regularities and their significance. Lancet 226, 698–703. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)92530-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJP, Osmond C. 1986. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet 1, 1077–1081. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91340-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. 2008. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl. J. Med. 359, 61–73. ( 10.1056/NEJMra0708473) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker DJ. 1994. Mothers, babies and diseases in later life. London, UK: BMJ Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridker PM, Cook N. 2004. Clinical usefulness of very high and very low levels of C-reactive protein across the full range of Framingham risk scores. Circulation 109, 1955–1959. ( 10.1161/01.cir.0000125690.80303.a8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson TA, et al. 2003. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice. Circulation 107, 499–511. ( 10.1161/01.CIR.0000052939.59093.45) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crimmins EM, Finch CE. 2006. Infection, inflammation, height, and longevity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 498–503. ( 10.1073/pnas.0501470103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller GE, Chen E, Fok AK, Walker H, Lim A, Nicholls EF, Cole S, Kobor MS. 2009. Low early-life social class leaves a biological residue manifested by decreased glucocorticoid and increased proinflammatory signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 14 716–14 721. ( 10.1073/pnas.0902971106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor SE, Lehman BJ, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE. 2006. Relationship of early life stress and psychological functioning to adult C-reactive protein in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 819–824. ( 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDade TW, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. 2006. Psychosocial and behavioral predictors of inflammation in middle-aged and older adults: the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychosom. Med. 68, 376–381. ( 10.1097/01.psy.0000221371.43607.64) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballou SP, Kushner I. 1992. C-reactive protein and the acute phase response. Adv. Internal Med. 37, 313–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black S, Kushner I, Samols D. 2004. C-reactive protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48 487–48 490. ( 10.1074/jbc.R400025200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Clos TW. 2000. Function of C-reactive protein. Ann. Med. 32, 274–278. ( 10.3109/07853890009011772) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg AH, Scherer PE. 2005. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 96, 939–949. ( 10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Shih J, Matias M, Hennekens CH. 1998. Prospective study of C-reactive protein and the risk of future cardiovascular events among apparently healthy women. Circulation 98, 731–733. ( 10.1161/01.CIR.98.8.731) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. 2001. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 286, 327–334. ( 10.1001/jama.286.3.327) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo H-K, Bean JF, Yen C-J, Leveille SG. 2006. Linking C-reactive protein to late-life disability in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J. Gerontol. A-Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 380–387. ( 10.1093/gerona/61.4.380) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenny NS, Yanez ND, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Hirsch CH, Tracy RP. 2007. Inflammation biomarkers and near-term death in older men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 165, 684–695. ( 10.1093/aje/kwk057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger WH, Heimovitz H, Cohen HJ, Wallace R. 1999. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am. J. Med. 106, 516–512. ( 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00066-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alley DE, Seeman TE, Ki Kim J, Karlamangla A, Hu P, Crimmins EM. 2006. Socioeconomic status and C-reactive protein levels in the US population: NHANES IV. Brain Behav. Immun. 20, 498–504. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.10.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nazmi A, Victora CG. 2007. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differentials of C-reactive protein levels: a systematic review of population-based studies. BMC Public Health 7, 212 ( 10.1186/1471-2458-7-212) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranjit N, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, Cushman M, Hanyu N, Seeman T. 2007. Socioeconomic position, race/ethnicity, and inflammation in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation 116, 2383–2390. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706226) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDade TW, Lindau ST, Wroblewski K. 2011. Predictors of C-reactive protein in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. J. Gerontol. B-Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 66, 129–136. ( 10.1093/geronb/gbq008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemingway H, Shipley M, Mullen MJ, Kumari M, Brunner E, Taylor M, Donald AE, Deanfield JE, Marmot M. 2003. Social and psychosocial influences on inflammatory markers and vascular function in civil servants (The Whitehall II study). Am. J. Cardiol. 92, 984–987. ( 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00985-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. 2007. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1319–1324. ( 10.1073/pnas.0610362104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDade TW, Rutherford J, Adair L, Kuzawa CW. 2010. Early origins of inflammation: microbial exposures in infancy predict lower levels of C-reactive protein in adulthood. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1129–1137. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.1795) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sattar N, McConnachie A, O'Reilly D, Upton MN, Greer IA, Smith GD, Watt G. 2004. Inverse association between birth weight and C-reactive protein concentrations in the MIDSPAN Family Study. Arterioscl. Throm. Vas. 24, 583–587. ( 10.1161/01.atv.0000118277.41584.63) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzoulaki I, et al. 2008. Size at birth, weight gain over the life course, and low-grade inflammation in young adulthood: northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 29, 1049–1056. ( 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn105) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer MS. 2000. Invited commentary: association between restricted fetal growth and adult chronic disease: it is causal? Is it important? Am. J. Epidemiol. 152, 605–608. ( 10.1093/aje/152.7.605) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanks N, Lightman SL. 2001. The maternal-neonatal neuro-immune interface: are there long-term implications for inflammatory or stress-related disease? J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1567–1573. ( 10.1172/JCI14592) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metzger MW, McDade TW. 2010. Breastfeeding as obesity prevention in the United States: a sibling difference model. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 22, 291–296. ( 10.1002/ajhb.20982) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Academy of Pediatrics. 2012. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 129, e827–e841. ( 10.1542/peds.2011-3552) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNICEF United Kingdom. 2013. Government recommendations See http://www.unicef.org.uk/BabyFriendly/About-Baby-Friendly/Breastfeeding-in-the-UK/Government-recommendations/.

- 35.CDC. 2012. Breastfeeding report card 2012, United States See http://www.cdcgov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard2htm.

- 36.Li R, Darling N, Maurice E, Barker L, Grummer-Strawn LM. 2005. Breastfeeding rates in the United States by characteristics of the child, mother, or family: the 2002 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics 115, e31–e37. ( 10.1542/peds.2004-0481) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. 2010. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 39, 263–272. ( 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braveman P, Barclay C. 2009. Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics 124(Suppl. 3), S163–S175. ( 10.1542/peds.2009-1100D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wooldridge JM. 2006. Introductory econometrics, 3. Mason, OH: Aufl Thomson South-Western. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paneth N, Susser M. 1995. Early origin of coronary heart disease (the Barker hypothesis). Br. Med. J. 310, 411–412. ( 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.411) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris KM.2011. Design features of Add Health. See http://www.cpcuncedu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/design%20paper%20WI-IVpdf .

- 42.Macy EM, Hayes TE, Tracy RP. 1997. Variability in the measurement of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: implications for reference intervals and epidemiological applications. Clin. Chem. 43, 52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ockene IS, Matthews CE, Rifai N, Ridker PM, Reed G, Stanek E. 2001. Variability and classification accuracy of serial high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurements in healthy adults. Clin. Chem. 47, 444–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Entzel P, Whitsel EA, Richardson A, Tabor J, Hallquist S, Hussey J, Halpern CT, Harris KM.2009. Cardiovascular and anthropometric measures. See http://www.cpcuncedu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/Wave%20IV%20cardiovascular%20and%20anthropometric%20documentation%20110209pdf .

- 45.McDade TW, Williams S, Snodgrass JJ. 2007. What a drop can do: dried blood spots as a minimally invasive method for integrating biomarkers into population-based research. Demography 44, 899–925. ( 10.1353/dem.2007.0038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDade TW, Burhop J, Dohnal J. 2004. High sensitivity enzyme immunoassay for C reactive protein in dried blood spots. Clin. Chem. 50, 652–654. ( 10.1373/clinchem.2003.029488) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucas A, Fewtrell MS, Cole TJ. 1999. Fetal origins of adult disease: the hypothesis revisited. Br. Med. J. 319, 245–249. ( 10.1136/bmj.319.7204.245) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pollitt RA, Kaufman JS, Rose KM, Diez-Roux AV, Zeng DL, Heiss G. 2007. Early-life and adult socioeconomic status and inflammatory risk markers in adulthood. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 22, 55–66. ( 10.1007/s10654-006-9082-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaffler A, Muller-Ladner U, Scholmerich J, Buchler C. 2006. Role of adipose tissue as an inflammatory organ in human diseases. Endocr. Rev. 27, 449–467. ( 10.1210/er.2005-0022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harder T, Bergmann R, Kallischnigg G, Plagemann A. 2005. Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 162, 397–403. ( 10.1093/aje/kwi222) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. 2002. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 7, 83 ( 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halfon N, Hochstein M. 2002. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Q 80, 433–479. ( 10.1111/1468-0009.00019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Pfeffer MA, Sacks F, Braunwald E. 1999. Long-term effects of pravastatin on plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. The cholesterol and recurrent events (CARE) investigators. Circulation 100, 230–235. ( 10.1161/01.CIR.100.3.230) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Clearfield M, Downs JR, Weis SE, Miles JS, Gotto AM., Jr 2001. Measurement of C-reactive protein for the targeting of statin therapy in the primary prevention of acute coronary events. N Engl. J. Med. 344, 1959–1965. ( 10.1056/NEJM200106283442601). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albert MA, Danielson E, Rifai N, Ridker PM. 2001. Effect of statin therapy on C-reactive protein levels: the pravastatin inflammation/CRP evaluation (PRINCE): a randomized trial and cohort study. JAMA 286, 64–70. ( 10.1001/jama.286.1.64) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomeo CA, Rich-Edwards JW, Michels KB, Berkey CS, Hunter DJ, Frazier AL, Willett WC, Buka SL. 1999. Reproducibility and validity of maternal recall of pregnancy-related events. Epidemiology 10, 774–777. ( 10.1097/00001648-199911000-00022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li R, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. 2008. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutr. Rev. 63, 103–110. ( 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00128.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. 2000. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl. J. Med. 342, 836–843. ( 10.1056/nejm200003233421202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring J, Ridker PM. 2004. C-reactive protein levels among women of various ethnic groups living in the United States (from the Women's Health Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 93, 1238–1242. ( 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhuiyan AR, Srinivasan SR, Chen W, Azevedo MJ, Berenson GS. 2011. Influence of low birth weight on C-reactive protein in asymptomatic younger adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. BMC Res. Notes 4, 71 ( 10.1186/1756-0500-4-71) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams M, Williams S, Poulton R. 2006. Breast feeding is related to C-reactive protein concentration in adult women. J. Epidemiol. Commun. H 60, 146–148. ( 10.1136/jech.2005.039222) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rudnicka AR, Owen CG, Strachan DP. 2007. The effect of breastfeeding on cardiorespiratory risk factors in adult life. Pediatrics 119, e1107–e1115. ( 10.1542/peds.2006-2149) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McDade TW. 2012. Early environments and the ecology of inflammation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17 281–17 288. ( 10.1073/pnas.1202244109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Field CJ. 2005. The immunological components of human milk and their effect on immune development in infants. J. Nutr. 135, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuzawa CW, Sweet E. 2009. Epigenetics and the embodiment of race: developmental origins of US racial disparities in cardiovascular health. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 21, 2–15. ( 10.1002/ajhb.20822) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth).