Abstract

Microbially influenced corrosion (MIC) of iron (Fe0) by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) has been studied extensively. Through a mechanism, that is still poorly understood, electrons or hydrogen (H2) molecules are removed from the metal surface and used as electron donor for sulfate reduction. The resulting ferrous ions precipitate in part with the sulfide produced, forming characteristic black iron sulfide. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens can also contribute to MIC. Incubation of pipeline water samples, containing bicarbonate and some sulfate, in serum bottles with steel coupons and a headspace of 10% (vol/vol) CO2 and 90% N2, indicated formation of acetate and methane. Incubation of these samples in serum bottles, containing medium with coupons and bicarbonate but no sulfate, also indicated that formation of acetate preceded the formation of methane. Microbial community analyses of these enrichments indicated the presence of Acetobacterium, as well as of hydrogenotrophic and acetotrophic methanogens. The formation of acetate by homoacetogens, such as Acetobacterium woodii from H2 (or Fe0) and CO2, is potentially important, because acetate is a required carbon source for many SRB growing with H2 and sulfate. A consortium of the SRB Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough and A. woodii was able to grow in defined medium with H2, CO2, and sulfate, because A. woodii provides the acetate, needed by D. vulgaris under these conditions. Likewise, general corrosion rates of metal coupons incubated with D. vulgaris in the presence of acetate or in the presence of A. woodii were higher than in the absence of acetate or A. woodii, respectively. An extended MIC model capturing these results is presented.

Keywords: microbially influenced corrosion, acetogens, methanogens, sulfate-reducing bacteria, microbial community, pyrosequencing

Introduction

Corrosion failures occur in water-transporting pipelines, when the anodic dissolution of iron (Fe0 → Fe2+ + 2e−) is coupled to the cathodic reduction of oxygen (2H+ + ½O2 + 2e− → H2O). Pipelines are generally subject to high corrosion rates, if oxygen is readily available as an electron acceptor. To limit corrosion, water transported through these pipelines is degassed and is kept anaerobic through the addition of chemical oxygen scavengers such as sodium bisulfite (SBS). Protons are reduced at the cathode (2H+ + 2e− → H2), instead of oxygen, under the resulting anaerobic conditions. This generally results in much lower corrosion rates, e.g., with linear polarization resistance (LPR) abiotic carbon steel corrosion rates of 0.26 and 0.11 mm/yr were observed under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, respectively, in a defined medium (Caffrey et al., 2008).

Hydrogenotrophic microorganisms consume cathodic hydrogen in a process that may contribute to microbially influenced corrosion (MIC). Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), using cathodic hydrogen to reduce sulfate to sulfide, are often associated with MIC. A mechanism, in which corrosive SRB remove electrons directly from the iron surface, has been proposed recently (Dinh et al., 2004; Enning et al., 2012). The resulting sulfide precipitates as characteristic, black iron sulfide, whereas the excess ferrous iron forms precipitates as iron carbonate, when bicarbonate is present (4Fe0 + 5H+ + 3HCO−3 + SO2−4 → FeS + 3FeCO3 + 4H2O).

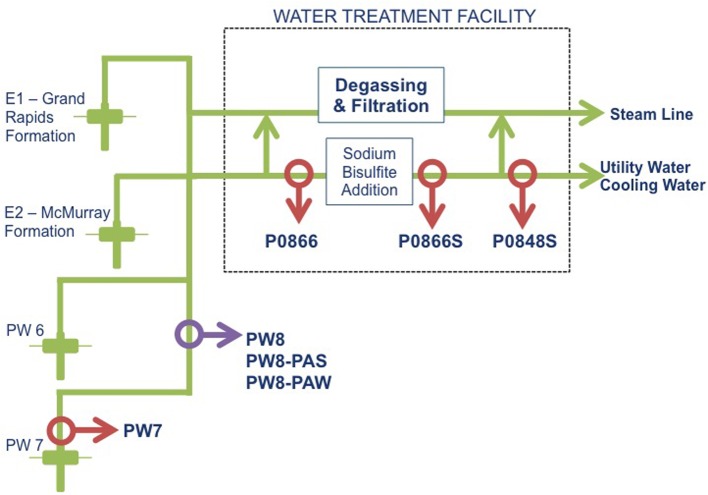

In the absence of sulfate, hydrogenotrophic methanogens can contribute to MIC by catalyzing 4Fe0 + 5H+ + 5HCO−3 → CH4 + 4FeCO3 + 3H2O (Dinh et al., 2004; Uchiyama et al., 2010). Methanogenesis with associated MIC was also demonstrated in a pipeline system, which transports brackish water (~5 g/L of NaCl) from the Grand Rapids and McMurray (GM) formations (Figure 1) for use in bitumen production by steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD), as shown by Park et al. (2011). This water lacked sulfate, but contained high concentrations of bicarbonate. SBS was injected in this system to decrease corrosion rates. Interestingly, injection of SBS led to a drastic change in microbial community composition, which was dominated by Desulfocapsa (class Deltaproteobacteria) downstream from the SBS injection point (Park et al., 2011). Desulfocapsa derives energy for growth from the disproportionation of bisulfite into sulfate and sulfide (Finster et al., 2013) and this organism clearly took advantage of a situation where low concentrations of bisulfite are provided continuously.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the water pipeline system from the SAGD site. Samples were collected at various points. Water was drawn up (PW7), taken to a water treatment facility (P0866) and treated with sodium bisulfite (P0866S and P0848S). A corrosion failure led to the collection of a pipe sample (PW8-PAS), which was transported with associated water (PW8-PAW). A water sample was also taken at this point (PW8).

During further studies of MIC-associated methanogenesis at this SAGD water distribution system we found that concentrations of acetate of up to 1 mM were also produced, suggesting involvement of hydrogenotrophic acetogens, catalyzing (4Fe0 + 6HCO−3 + 5H+ → CH3COO− + 4FeCO3 + 4H2O). These microorganisms normally produce acetate from hydrogen and carbon dioxide (Hu et al., 2013; Straub et al., 2014). We obtained another set of samples from a fresh water well from the same SAGD site (Figure 1: PW7). Water samples from this well had low concentrations of NaCl (0–200 ppm) and sulfate (0–64 ppm) and high concentrations of bicarbonate (500 ppm), as indicated in Table 1. These were used to further explore the possible production of acetate from steel as a novel MIC reaction.

Table 1.

Water chemistry of samples obtained for this study.

| Sample | pH | Sulfate | Sulfide | Ferrous iron | Acetate | Bicarbonatea | Sodiuma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PW7 | 7.59 | 0 | 0.5 | 4.64 | 0 | 530 | 81 |

| P0866 | 7.51 | 64.2 | 0.36 | 0 | 0 | 510 | 60 |

| P0866S | 7.32 | 5.08 | 0.03 | 5.3 | 0 | 520 | 100 |

| P0848S | 7.47 | 5.95 | 0.03 | 3.3 | 0 | 530 | 230 |

| PW8 | 6.73 | 34.87 | 0 | 2.33 | 12.15 | NDb | NDb |

| PW8-PAW | 6.89 | 26.52 | 0 | 5.65 | 6.17 | NDb | NDb |

| PW8-PAS | 6.71 | 62.36 | 1.52 | 1546 | 18.66 | NDb | NDb |

All concentrations are in ppm (mg/L).

Data provided by company;

Not determined.

Materials and methods

Field samples

Field samples were acquired from the utility water system at a SAGD site in northern Alberta. Water samples (2 L) were shipped in 1 L Nalgene (VWR International, Edmonton, AB) bottles filled to the brim to exclude oxygen. Sample PW7 was a freshwater sample from near the well-bore region with a temperature of 11°C. Sample P0866, was immediately upstream of the water treatment facility, where SBS was injected and was between 20 and 25°C. Samples P0866S and P0848S were taken downstream from this facility (Figure 1). All samples were stored in a Coy (Grass Lake, MI) anaerobic hood with an atmosphere of 90% N2 and 10% CO2 (N2-CO2, Praxair, Calgary, AB). A pipe segment representing a corrosion failure was also obtained, along with water sample PW8 from this site (Figure 1). The pipe segment was shipped in a bucket, together with pipe-associated water (PW8-PAW). Pipeline associated solids (PW8-PAS) were obtained by scraping the pipe segment in the anaerobic hood and suspending the scrapings in 0.2 μm filtered PW8-PAW, representing 10% of the internal volume of the pipe segment, as described elsewhere (Park et al., 2011). Upon arrival, 1 L of each water sample was filtered using a 0.2 μm Millipore nylon membrane (VWR International, Edmonton, AB) to collect biomass. This was immediately frozen at −80°C for use in DNA extraction.

While some water chemistry data were provided with the samples (bicarbonate, sodium), their chemical composition was characterized further. Sulfide concentrations were assessed colorimetrically using N, N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (Trüper and Schlegel, 1964). Aqueous ferrous iron concentrations were assessed using a colorimetric assay using ferrozine (Park et al., 2011). Ammonium concentrations were assayed using the indophenol method and the pH of the samples was measured using a Thermo Scientific Inc. Orion 370 model pH meter (VWR International, Mississauga, ON). To measure acetate concentrations, a high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) from Waters (Mississauga, ON), model 515, equipped with a Waters 2487 model UV detector set at 220 nm and an organic acid column (250 × 4.6 mm, Alltech Prevail, Guelph, ON) eluted with 25 mM KH2PO4 of pH of 2.5 was used. Samples (1 mL) were centrifuged at 13,300 rpm for 5 min, 300 μ L of the resulting supernatant was acidified using 20 μ L of 1 M H3PO4, and eluted at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. Sulfate concentrations were monitored using a Waters 600 model HPLC equipped with a Waters 432 conductivity detector and an IC-PAK anion column (150 × 4.6 mm, Waters) eluted with 24% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, 2% butanol, and 2% borate-gluconate concentrate. Following centrifugation 100 μ L of the sample supernatant was added to 400 μ L of the acetonitrile solution and eluted at 2 mL/min.

Two carbon steel coupons (American Society for Testing and Materials, ASTM a366, containing 0.015% carbon, 5 × 1 × 0.1 cm) were incubated with 50 mL of each water sample in a 120 mL serum bottle. The coupons were cleaned according to National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE) protocol RP0775-2005. The coupons were polished with 400 grit sandpaper, washed in a dibutylthiourea solution for 2 min, followed by a saturated bicarbonate solution for 2 min. The coupons were briefly rinsed in deionized water and then acetone and quickly dried in a stream of air. The coupons were weighed three times using an analytical balance and the average weight was recorded as the starting weight. The serum bottles were sealed with a headspace containing N2-CO2. During incubation, headspace methane and aqueous acetate concentrations were monitored. For methane measurements, 0.2 mL of the headspace was sampled periodically using a syringe that had been flushed with N2-CO2 and injected into a Hewlett-Packard (Mississauga, ON) model 5890 gas chromatograph at 150°C, equipped with a flame-ionizing detector set to 200°C and a stainless steel column (0.049 × 5.49 cm, Porapak R 80/100, Supelco, Oakville, ON). Following incubation, surface deposits were removed from each coupon using a non-scratching wipe. The coupons were cleaned according to the NACE protocol and again weighed three times. The weight loss (Δ W) was converted into a general corrosion rate (CR, mm/year) by the equation: CR = 87600 × Δ W/A × T × D where A is the coupon surface area (cm2), T is the incubation time (hours), and D is steel density (7.85 g/cm3), as described previously (Park et al., 2011).

Field sample enrichments

Two carbon steel coupons (ASTM a366) were incubated in 50 mL of anaerobic Coleville synthetic brine (CSB-K) medium (Callbeck et al., 2013) in sealed 120 mL serum bottle microcosms with N2-CO2. Each microcosm was anaerobically inoculated with 2.5 mL of each field sample (5% inoculum of field sample). As a control, two corrosion coupons were incubated anaerobically with 50 mL of medium only. The incubation periods lasted between 8 and 16 weeks at 32°C, under constant shaking at 100 rpm. During this time, concentrations of methane were measured using gas chromatography and concentrations of acetate were measured using HPLC. For incubations with PW8, PW8-PAW, or PW8-PAS only corrosion rates were determined from metal weight loss. For incubations involving samples PW7, P0866, P0866S, and P0848S, biomass was also collected from each microcosm. The metal coupons were removed from the microcosm and washed with CSB-K medium to remove any unattached material. The coupons were gently scraped with a blade and the resulting biomass was considered representative of the biofilm population. The coupons were then cleaned according to the NACE protocol, and general corrosion rates were determined.

DNA isolation from the field samples and enrichments

Biomass, collected from each field sample and from the biofilm fractions, was used for DNA extraction. DNA was extracted, using a bead-beating procedure outlined by the manufacturer of the FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA). DNA was eluted using 10 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.5 (Buffer EB from the QIAquick kit, Qiagen, Toronto, ON). The concentration of DNA extracted from each sample was quantified using the Qubit Fluorometer, and Quant-iT™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON).

Community analysis by pyrosequencing

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes from isolated community DNA was performed using primers 926Fw (AAACTYAAAKGAATTGRCGG) and 1392R (ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC) using the Taq Polymerase I Kit (Qiagen, Toronto, ON). PCR was for 5 min at 95°C, followed by 20 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 45 s at 55°C, and 90 s at 72°C and finally 7 min at 72°C. A second PCR step used FLX titanium amplicon primers 454_RA_X and 454T_FwB for an additional 10 cycles. These have the sequences for primers 926Fw and 1392R at their 3′ ends. Primer 454T_RA_X has a 25 nucleotide A-adaptor (CGTATCGCCTCCCTCGCGCCATCAG) and a 10 nucleotide multiplex identifier barcode sequence X. Primer 454T_FwB has a 25 nucleotide B-adaptor sequence (CTATGCGCCTTGCCAGCCCGCTCAG). The resulting 16S rRNA PCR amplicons were purified and sent for pyrosequencing to the Genome Quebec and McGill University Innovation Centre (Montreal, QC). Pyrosequencing was done using a Genome Sequencer FLX Instrument, using a GS FLX Titanium Series Kit XLR70 (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Laval, QC). Pyrosequencing and bioinformatic analysis of the sequences obtained have all been described elsewhere (Park et al., 2011; Soh et al., 2013).

Analysis of pure cultures of an SRB and an acetogen

Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough and Acetobacterium woodii (DSM 1030) were used as model SRB and acetogen strains, respectively and were grown in Widdel-Pfennig (WP) medium with 10 mM sulfate and 30 mM NaHCO3 (Caffrey et al., 2007). Microcosms were inoculated with a culture of A. woodii, a culture of D. vulgaris, a co-culture of both strains, or no inoculum. A fifth microcosm containing a culture of D. vulgaris was amended with 3 mM acetate. Incubations were in 160 mL serum bottles containing 40 mL of medium and a headspace of 80% H2 and 20% CO2 Growth was measured by determining the optical density at 600 nm using a Shimadzu model 1800 UV spectrophotometer (Mandel, Guelph, ON) and by monitoring concentrations of acetate, sulfate, and sulfide.

To test corrosivities of these cultures, two carbon steel corrosion coupons (ASTM a366) were added to each of the microcosms. The headspace of these microcosms was either 80% H2 and 20% CO2, 16% H2 and 84% CO2 or N2-CO2, as indicated. Concentrations of acetate and sulfate were measured during incubation. Following incubation, the coupons were cleaned as per NACE protocol, metal weight loss was determined and this was converted into general corrosion rates.

Results

Methane and acetate production from steel coupons

The samples obtained from the water gathering system for a SAGD facility are indicated in Figure 1. Relative to samples obtained previously from the GM formations (Park et al., 2011), these had lower concentrations of NaCl (0–200 ppm, compared to 4000–6000 ppm for GM) and higher concentrations of sulfate (0–64 ppm, as compared to 0–2 ppm for GM). Both sets of samples had high bicarbonate concentrations (520 ppm, as compared to 400–1600 ppm for GM). Sulfide (0–1.5 ppm), ammonium (not shown) and acetate (0–19 ppm) were present in low concentrations (Table 1). Ferrous iron was low, except in the pipe-associated solids sample (Table 1: PW8-PAS), which had 1546 ppm, indicative of corrosion (Park et al., 2011).

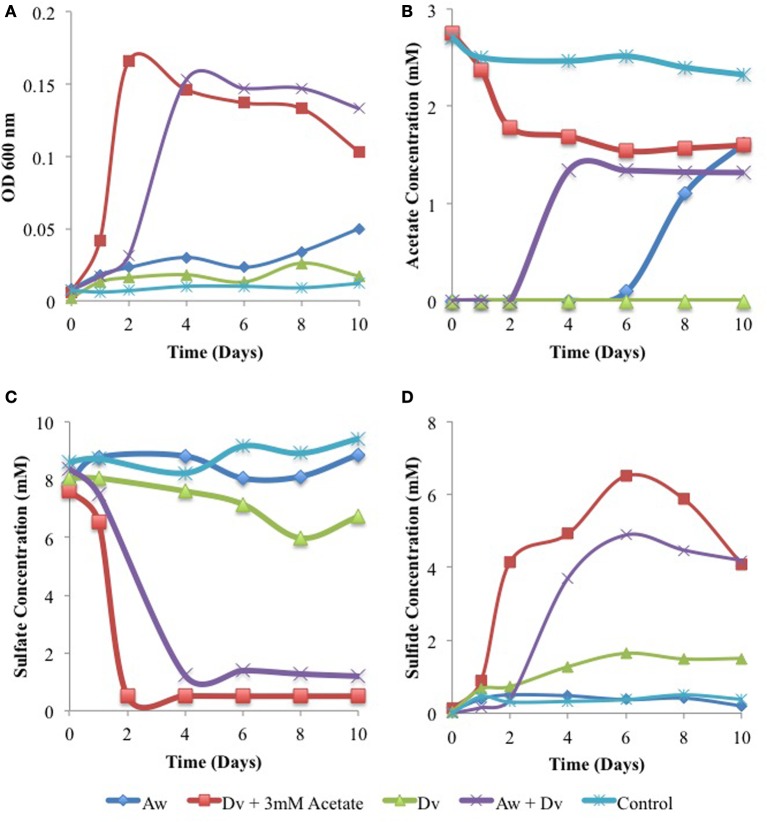

Incubation of samples P0866, P0866S, and P0848S with carbon steel coupons and a headspace of N2-CO2 for 70 days gave formation of 2.3, 1.0, or 2.6 mM headspace methane, respectively (Figure 2A). No significant methane was formed in incubations with sample PW7 or the water-only control. Weight loss corrosion rates were higher (p < 0.00032) for incubations with samples P0866, P0866S, and P0848S (Figure 2B: average 0.018 ± 0.0040 mm/yr, n = 6) than with sample PW7 or the water-only control (Figure 2B: average 0.0060 ± 0.00091 mm/yr, n = 4). The formation of acetate was evaluated in a separate experiment indicating formation of 0.45 to 3.2 mM acetate in the aqueous phase of these incubations, whereas no acetate was formed in the water-only control (Figure 2C). Neither methane nor acetate were formed in the absence of steel coupons (results not shown).

Figure 2.

Methane production (A) was monitored as field samples were incubated in the presence of carbon steel coupons and the associated corrosion rates (B) were determined using metal weight loss. Acetate production (C) was monitored in an independent incubation of these field samples in the presence of carbon steel coupons. Data represent results from separate incubations with two coupons each.

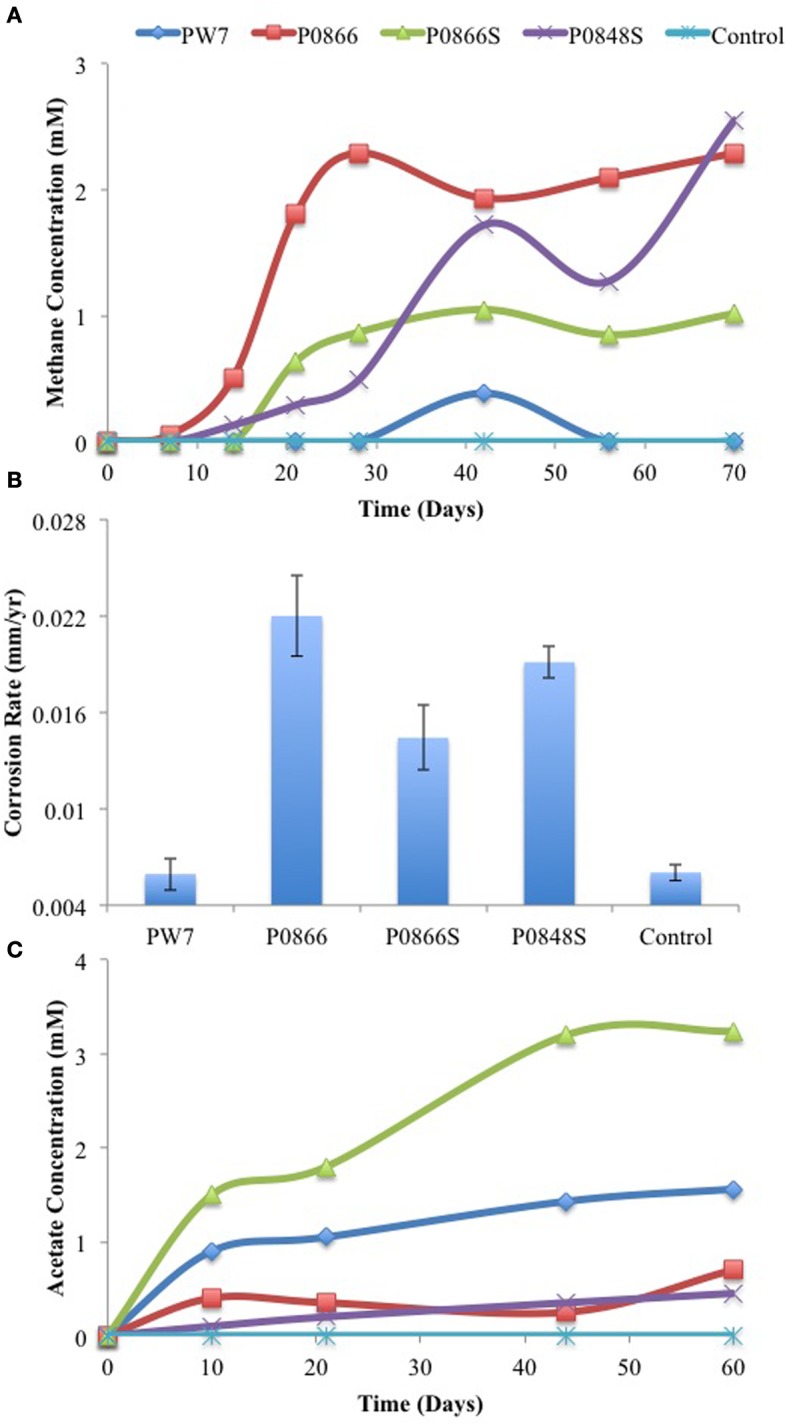

In a variation of this experiment serum bottles with 70 mL CSB-K medium, containing carbon steel coupons, 30 mM of bicarbonate and a headspace of N2-CO2 were inoculated with 3.5 ml of field sample. Acetate and methane were monitored as a function of time, and weight loss corrosion was determined at the end of the experiment. Production of up to 0.6 mM acetate was seen for all samples. This appeared to precede production of methane and go through a maximum (Figure 3A). Production of 1.9 to 3.0 mM headspace methane was observed with all samples, except P0866 (Figure 3B). The biofilms present on the coupons were isolated prior to processing of the coupons for measuring weight loss corrosion. The corrosion rates observed for incubations with samples PW7, P0866S, and P0848S (average 0.0068 ± 0.0012 mm/year, n = 6) were higher (p < 0.00076) than those with P0866 and the medium control (average 0.0035 ± 0.00031 mm/year, n = 4), as shown in Figure 3C. Hence, although both acetate and methane were formed as part of the corrosion process, the formation of headspace methane appeared to be correlated with the corrosion rate, i.e., P0866S, the sample with the highest corrosion rate (0.0083 mm/yr) also had the highest headspace methane concentration (3.0 mM).

Figure 3.

Field samples were incubated in CSB-K medium with carbon steel coupons. Acetate (A) and methane (B) concentrations were monitored during incubation. Corrosion rates (C) were determined from metal weight loss. Data represent results from separate incubations with two coupons each.

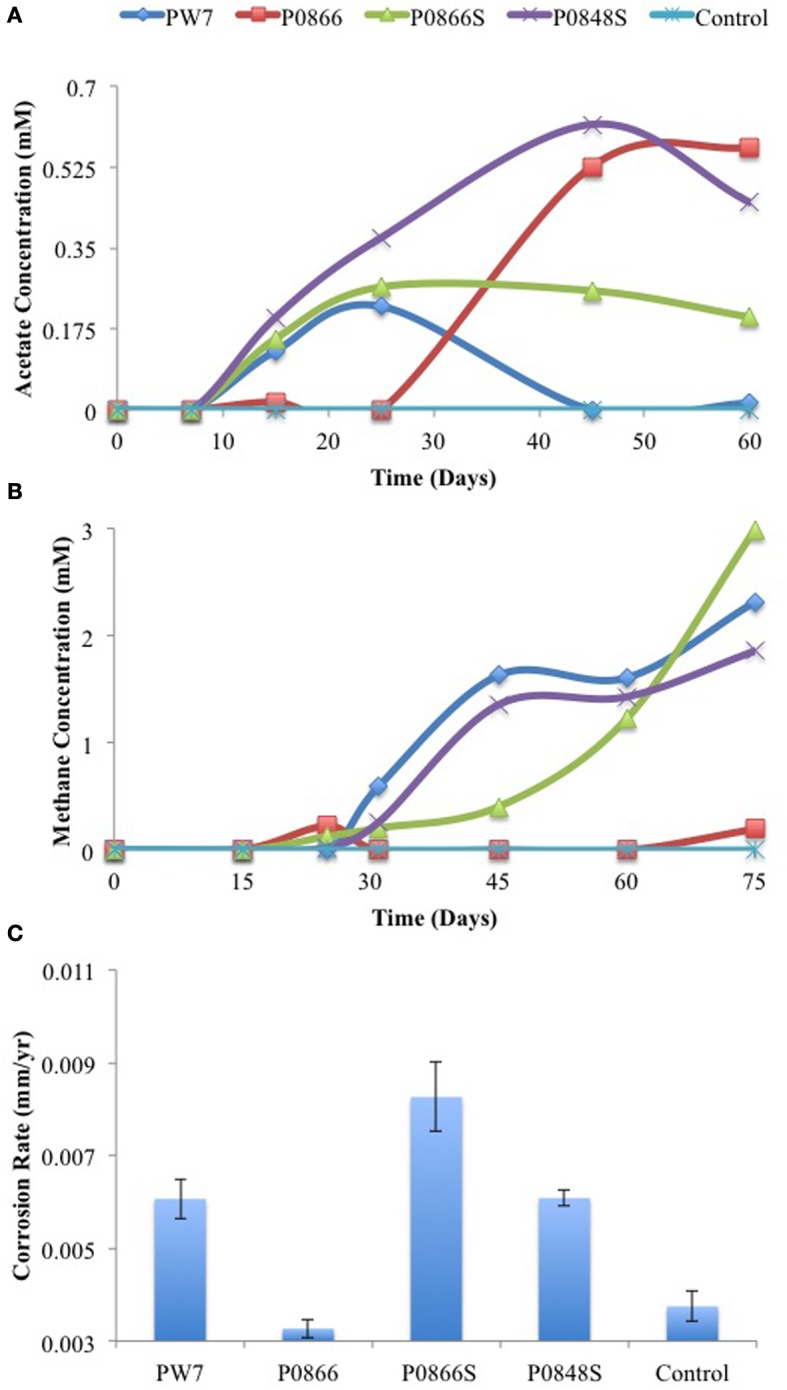

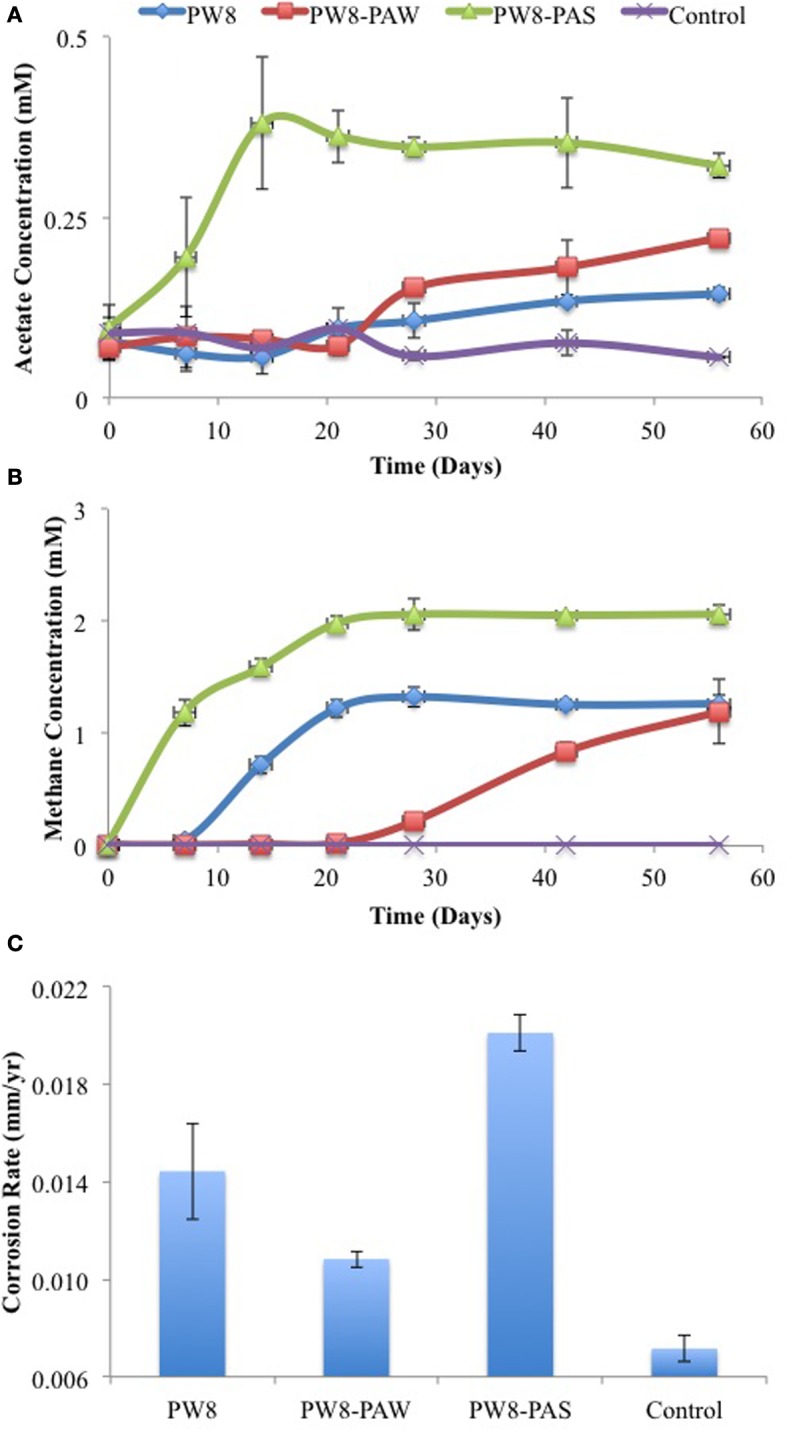

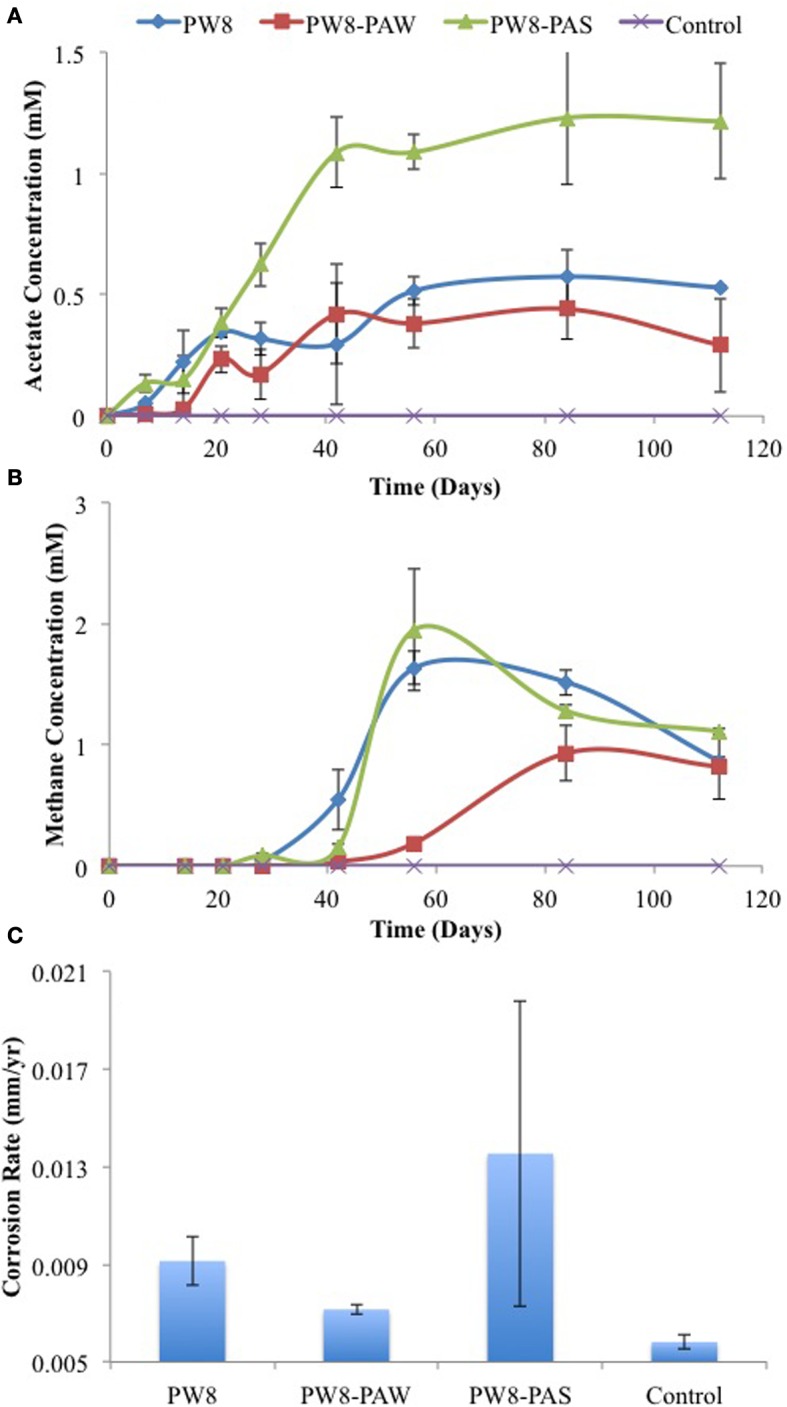

Similar results were obtained with samples PW8, PW8-PAW, and PW8-PAS, the latter representing pipe-associated solids suspended in microfiltered pipe-associated water (PW8-PAW). Incubation of metal coupons in these samples gave up to 0.38 mM acetate in the aqueous phase and 1 to 2 mM headspace methane (Figures 4A,B). The highest concentrations of acetate and methane were produced in incubations with PW8-PAS, which also had the highest corrosion rate (p < 0.0026) at 0.020 mm/yr (Figure 4C). When these field samples were inoculated in CSB-K medium, production of up to 1.2 mM acetate was seen to precede production of up to 2 mM of headspace methane (Figures 5A,B). Acetate and methane production were observed in incubations with PW8, PW8-PAW, and PW8-PAS, which had higher corrosion rates (p < 0.12) (average 0.0099 ± 0.0049 mm/yr, n = 12) than the uninoculated control (0.0058 ± 0.00042 mm/yr, n = 4) (Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

Field samples (PW8, PW8-PAW, PW8-PAS) were incubated with carbon steel coupons. Acetate (A) and methane (B) concentrations were monitored during incubation. Corrosion rates (C) were determined from metal weight loss. Data represent average results from two separate incubations with two coupons each.

Figure 5.

Field samples were incubated in CSB-K medium with carbon steel coupons. Acetate (A) and methane (B) concentrations were monitored during incubation. Corrosion rates (C) were determined from metal weight loss. Data represent average results from two separate incubations with two coupons each.

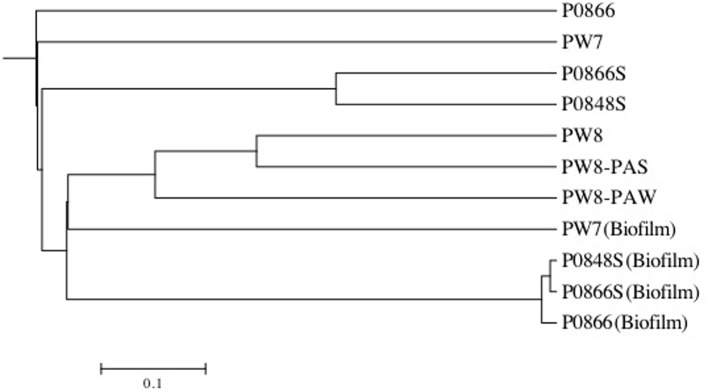

Microbial community compositions

Pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA amplicons for all seven field samples and for four coupon enrichment biofilms, gave 1357 to 6417 quality controlled reads for each sample (Table 2). The compositions of the microbial communities derived from these results are compared in Figure 6. Although the water samples were all from a single pipeline system, it is evident that the microbial communities in water samples retrieved along the flow path were distinct. The community of PW7 near the fresh water producing well-differed from those of PW8 and P0866, both further downstream and all of these were distinct from the communities at P0866S and P0848S downstream from the SBS injection point (Figures 1, 6). Microbial communities of PW8-PAS and PW8-PAW formed a separate branch in the dendrogram together with that of PW8. Communities in coupon enrichment biofilms differed significantly from those in field samples (Figure 6). Microbial communities formed following incubation with P0866, P0866S, and P0848S were very similar, whereas PW7 (Biofilm) was distinct from this cluster (Figure 6).

Table 2.

Distribution of taxa (%) over high-quality reads.

| Fraction (%) of taxa for each sample | Fraction (%) of all reads | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PW7 V12_433 | P0866 P0866 | P0866S V12_460 | P0848S V20_797 | PW8 V22_924 | PW8_PAW V22_925 | PW8_PAS V22_926 | PW7 (Biofilm) V15_602 | P0866 (Biofilm) V15_607 | P0866S (Biofilm) V15_608 | P0848S (Biofilm) V15_609 | ||

| Number of high quality reads | 4016 | 7093 | 6417 | 1357 | 4343 | 4403 | 4520 | 2427 | 2205 | 5474 | 3877 | |

| TAXON | ||||||||||||

| Family Methanobacteriaceae | 0.00 | 1.41 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 6.86 | 0.18 | 8.72 | 0.21 | 71.47 | 87.07 | 79.80 | 23.30 |

| Genus Desulfocapsa | 2.62 | 0.41 | 95.76 | 95.28 | 7.07 | 1.23 | 14.74 | 0.82 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 19.84 |

| Genus Methanosaeta | 0.97 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 14.46 | 16.53 | 18.30 | 17.14 | 7.08 | 0.06 | 2.71 | 7.04 |

| Genus Pseudomonas | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 52.82 | 9.57 | 3.16 | 8.92 | 6.87 |

| Genus Acidovorax | 61.70 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 5.94 |

| Family Rhodocyclaceae | 0.37 | 48.23 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.60 |

| Genus Dietzia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 25.91 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.36 |

| Genus Desulfurivibrio | 0.08 | 23.52 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.15 |

| Genus Acetobacterium | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 5.58 | 2.93 | 0.05 | 4.86 | 4.02 | 1.67 |

| Genus Desulfovibrio | 0.92 | 4.41 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 9.69 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 1.54 |

| Genus Methanothermobacter | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 8.73 | 6.93 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.45 |

| Genus Castellaniella | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.13 | 4.09 | 2.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.32 |

| Genus Methanoculleus | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 3.36 | 4.77 | 3.94 | 0.95 | 0.64 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 1.28 |

| Genus Desulfosporosinus | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 13.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.26 |

| Genus Desulfobulbus | 0.87 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 4.81 | 1.20 | 2.68 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| Genus Methanobacterium | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.85 | 1.23 | 1.17 | 4.29 | 0.27 | 2.25 | 0.05 | 0.93 |

| Genus Geobacter | 8.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.78 |

| Genus Methanocalculus | 1.12 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 1.98 | 2.08 | 0.87 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.77 |

| Genus Marinobacterium | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.89 | 1.02 | 2.56 | 1.59 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.69 |

| Genus Desulfomicrobium | 0.10 | 5.43 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 1.02 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.64 |

| Phylum Firmicutes | 0.25 | 2.33 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| Family Rhodocyclaceae | 0.05 | 1.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 3.23 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.43 |

| Genus Methanolinea | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 1.75 | 1.13 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.41 |

| Genus Comamonadaceae | 3.36 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.39 |

| Genus Marinobacter | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.85 | 1.27 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.39 |

| Phylum Crenarchaeota | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 2.37 | 1.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| Genus Citricoccus | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.93 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.36 |

| Genus Nitrospira | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.20 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.34 |

| Kingdom Bacteria | 0.90 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.31 |

| Genus Gallionella | 1.52 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| Genus Planococcus | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 3.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 |

| Genus Methanolobus | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| Sum | 85.41 | 88.59 | 96.70 | 97.86 | 71.43 | 79.65 | 91.95 | 86.61 | 93.65 | 97.84 | 97.34 | 89.73 |

Taxa in abundance greater than 1% are bolded. Taxa were ranked according to their overall abundance in the 16S rRNA amplicons for the samples. Data are for field samples (water) and the communities growing on steel coupons (biofilm) in incubations of field samples in medium with bicarbonate, but without sulfate. Only taxa with an average abundance in excess of 0.25% are shown.

Figure 6.

Tree generated using UPGMA algorithm with distance between communities calculated using thetaYC coefficient in the Mothur software package. Tree was visualized with Mega. All field samples formed a tree separate from all enrichment samples. Water field samples were distinct from pipeline-associated samples.

The microbial community of water sample PW7 was dominated by Betaproteobacteria of the genus Acidovorax (Table 2: 61.70%). This taxon had decreased to 2.49% of the community in water sample PW8, which also harbored significant fractions of methanogens of the class Methanobacteriaceae (16.44%), the genera Methanosaeta (14.46%) and Methanoculleus (3.36%), as well as of Deltaproteobacteria of the genera Desulfocapsa (7.07%) and Desulfobulbus (4.81%). The pipeline solids at this location, PW8-PAS, also harbored high fractions of Deltaproteobacteria/Desulfovibrio (9.69%), of Firmicutes/Acetobacterium (5.58%), and of Firmicutes/Desulfosporosinus (13.45%). Many of these taxa use hydrogen (and possibly Fe0) as electron donor for the reduction of CO2 to methane or to acetate (Acetobacterium) or for the reduction of sulfate to sulfide (Desulfobulbus, Desulfosporosinus, Desulfovibrio). The water associated with the pipe sample (PW8_PAW) had a high fraction of Dietzia (25.91%), which has been associated with hydrocarbon degradation (Bihari et al., 2011). The community composition of water sample P0866, taken further downstream, had high fractions of Betaproteobacteria/Rhodocyclaceae (48.23%), capable of nitrate reduction and of Deltaproteobacteria of the genera Desulfurivibrio (23.52%), Desulfovibrio (4.41%), and Desulfomicrobium (5.43%). Treatment with SBS gave rise to communities dominated by Desulfocapsa in water samples P0866S (95.76%) and P0848S (95.28%), which grows by disproportionation of bisulfite to sulfate and sulfide, as discussed elsewhere (Park et al., 2011). Hence, a succession of communities is present along the water flow path, with a very strong shift being observed by the addition of SBS. It is interesting that the microbial communities in the water samples, obtained from the water-transporting pipeline studied here, appeared to change so rapidly as a function of distance (Figure 6). This would seem to be at odds with the fact that the transport time of water from PW7 to P0848S is less than 1 day. These large changes in community composition may indicate that most biomass grows on the pipe walls as biofilms, is sloughed off at a high rate and appears to dominate the microbial community compositions seen. This explains why Desulfocapsa becomes a major community component immediately downstream from the SBS injection point (Table 2, Figure 1). The planktonic population would not be able to adjust in such a short time, but if the Desulfocapsa is biofilm-grown, it may continuously be swept into the flowing water.

Incubation of field samples with CSB-K medium, which contains CO2 and bicarbonate but lacks sulfate, in the presence of metal coupons led to their colonization by Methanobacteriaceae, which were present at 71.75, 89.31, and 79.86% in incubations with P0866, P0866S, and P0848. In the incubation PW7, only 4.49% of the reads were of the class Methanobacteriaceae. The latter biofilm had a high fraction of the acetotrophic methanogen Methanosaeta (17.14%), as well as of Pseudomonas (52.82%). Compared to the field samples, the biofilm communities also showed an increased presence of the acetogen Acetobacterium (Table 2). The colonization of carbon steel coupons by methanogens and acetogens (Table 2) can explain the production of acetate and methane observed in these incubations (Figure 3).

Growth of and corrosion by a pure culture consortium of an SRB and an acetogen

SRB of the genus Desulfovibrio or Desulfomicrobium need acetate as a carbon source when deriving energy for growth from reduction of sulfate with H2 or Fe0 (Badziong et al., 1979; Dinh et al., 2004; Caffrey et al., 2007; Enning et al., 2012). When acetate is absent or limiting, this can in principle be provided by acetogens from H2 (or Fe0) and CO2. In order to test this hypothesis we studied the growth of the model SRB Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough and the model acetogen Acetobacterium woodii in WP medium, containing bicarbonate and sulfate and a headspace of 80% H2 and 20% CO2. A monoculture of A. woodii grew poorly in this medium as judged by turbidity (Figure 7A) and produced up to 1.6 mM acetate after 10 days (Figure 7B). A monoculture of D. vulgaris did not grow (Figure 7A), did not have detectable acetate (Figure 7B) and reduced only 2 mM sulfate to sulfide (Figures 7C,D). Addition of 3 mM acetate to the monoculture of D. vulgaris gave strong growth, sulfate reduction, and sulfide production, while using 1.5 mM of added acetate. Following a lag phase of 2 days needed for the production of 1.3 mM acetate (Figure 7B), the co-culture of D. vulgaris and A. woodii exhibited similar growth, sulfate reduction and sulfide production as the monoculture of D. vulgaris with added acetate. No sulfate reduction or acetate production was seen in the inoculum-free control. Hence, A. woodii can provide the acetate needed by D. vulgaris for growth under chemolithotrophic conditions.

Figure 7.

Growth physiology of D. vulgaris (Dv) and A. woodii (Aw) monocultures and a co-culture in closed serum bottles under an atmosphere of 80% H2, 20% CO2. Cell density (A), acetate concentrations (B), sulfate concentrations (C), and sulfide concentrations (D). Data represent results from separate incubations without coupons present.

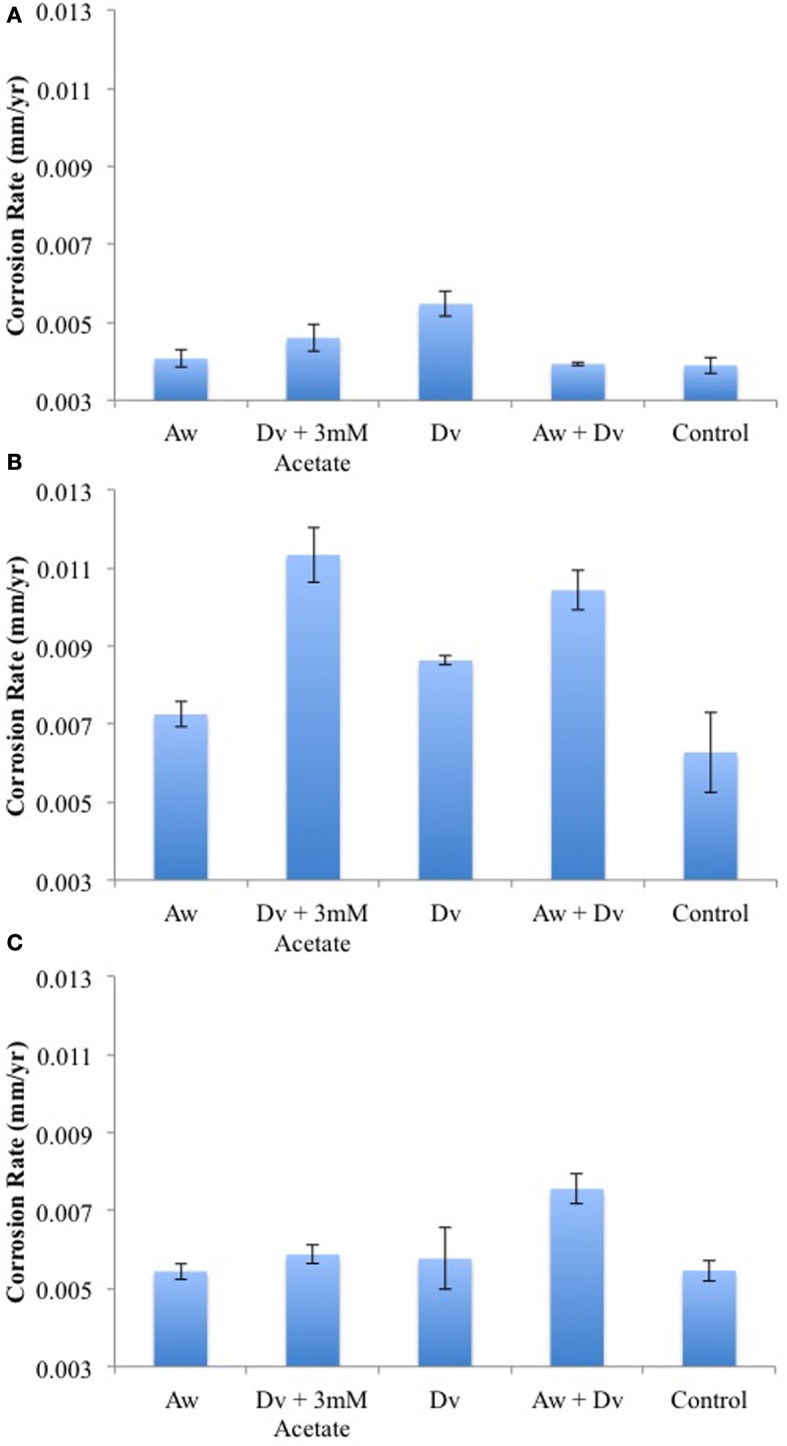

When carbon steel coupons were added to serum bottles, containing WP medium with sulfate and bicarbonate and a headspace of N2-CO2 and inoculated with D. vulgaris, D. vulgaris and 3 mM acetate, A. woodii, D. vulgaris, and A. woodii, or no inoculum, similar corrosion rates were observed of 0.0039 to 0.0055 mm/yr in all incubations (Figure 8C). This indicates that Fe0 alone is not a good electron donor for sulfate or carbon dioxide reduction by these two type cultures. In order to determine whether Fe0 can be used as an electron donor co-metabolically with H2, the experiment was repeated with a headspace of 80% (vol/vol) H2 and 20% CO2 (excess H2 for reduction of 10 mM sulfate) or 16% H2 and 84% CO2 (insufficient H2 for reduction of 10 mM sulfate). The highest corrosion rates were observed with limiting H2 for incubations with D. vulgaris and 3 mM acetate (0.0113 mm/yr) or with the coculture of D. vulgaris and A. woodii (0.0104 mm/yr), as shown in Figure 8B. These were higher (p < 0.000068) than the corrosion rates observed for incubations with D. vulgaris alone without added acetate, with A. woodii alone or with the uninoculated control (average 0.0074 ± 0.0015 mm/yr, n = 12). In the presence of excess H2 lower corrosion rates, between 0.0054 and 0.0059 mm/yr, were observed for all incubations except for the co-culture, which was somewhat higher (0.0076 mm/yr), as shown in Figure 8A. Overall, these results indicate that the co-culture of D. vulgaris and A. woodii can co-metabolically corrode carbon steel at a rate comparable to that when acetate is provided directly to the D. vulgaris culture.

Figure 8.

Corrosion rates of carbon steel coupons incubated in closed serum bottles with monocultures and a coculture of A. woodii (Aw) and D. vulgaris (Dv) an atmosphere of either (A) 90% N2, 10% (B) 16% H2, 84% CO2,or (C) 80% H2, 20% CO2. Control bottles had no inoculum. Data represent average results from two separate incubations with two coupons each.

Discussion

The role of acetic acid and CO2 in the anaerobic corrosion of steel has been studied extensively. The presence of acetic acid is generally considered corrosive even at moderate concentrations (100 ppm). Although this may be credited to a pH-effect, since protons are consumed in cathodic corrosion reactions, it appears that acetate, the predominant form at higher pH, is also corrosive (Hedges and McVeigh, 1999; George et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2008). The potential role of microorganisms in the acetate-CO2 corrosion landscape has been reviewed by Suflita et al. (2008). Anaerobic consortia produce acetic acid and CO2 by fermentation of carbohydrates or of oil hydrocarbons (Suflita et al., 2008; Callbeck et al., 2013). Acetogenic bacteria, such as A. woodii, can also produce acetic acid from H2 and CO2, using the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway to synthesize acetyl-CoA (Schiel-Bengelsdorf and Dürre, 2012; Leang et al., 2013).

As shown here, anaerobic consortia in samples from a SAGD water gathering system were able to produce methane, but also acetate in the presence of steel coupons (Figures 2–5). The production of methane using iron as an electron donor for reduction of CO2 is well-known. Highly corrosive methanogens, which like highly corrosive SRB may be able to extract electrons directly from the steel surface, have been isolated (Daniels et al., 1987; Dinh et al., 2004; Uchiyama et al., 2010). However, the production of acetate from iron has not previously been demonstrated, although the possibility has been discussed (Phelps, 1991; Suflita et al., 2008). Acetate production was shown when coupons were incubated directly with field samples (Figures 2, 4) and when coupons were incubated with CSB-K medium inoculated with the same field samples. The concentration of acetate formed in the aqueous phase tended to be less than that of methane in the headspace. Acetate formation appeared to precede methane formation (Figure 3). The presence of significant fractions of the acetotrophic methanogen Methanosaeta in the coupon-attached biofilms (Table 2) suggests that the acetate formed by acetogens may subsequently be converted into methane and CO2.

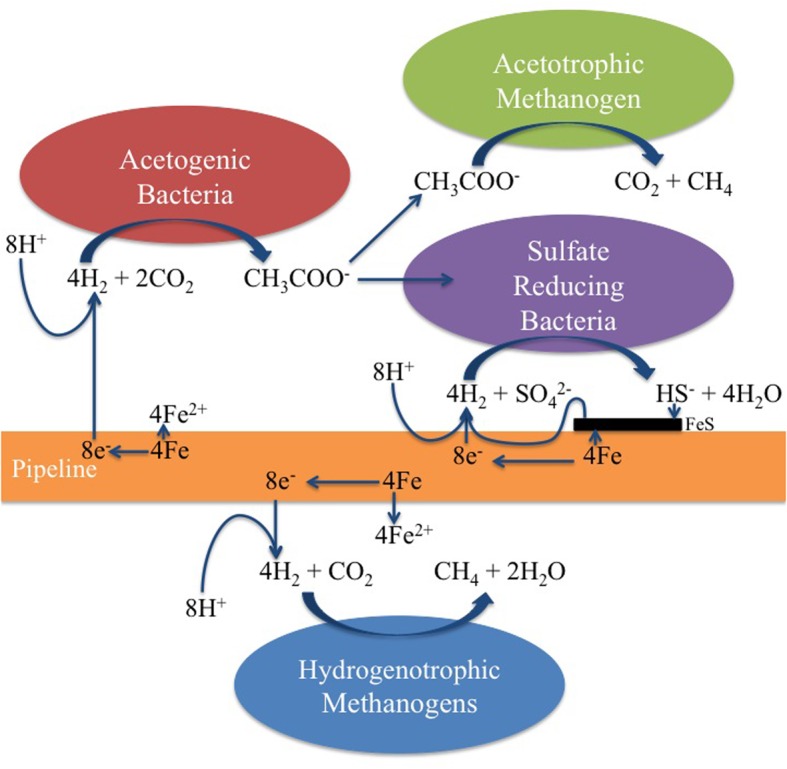

These features are captured in the extended MIC model shown in Figure 9. We have shown the uptake of reducing equivalents (H+ + e−) as dihydrogen (H2), realizing that direct uptake of electrons is another mechanism that has been proposed (Dinh et al., 2004; Enning et al., 2012). Accordingly, hydrogenotrophic acetogens, methanogens, or SRB could all contribute directly to corrosion by using metallic iron as an electron donor. The combined action of hydrogenotrophic acetogens and acetotrophic methanogens would be the same as that of hydrogenotrophic methanogens alone. In the coupon-attached biofilms for P0866, P0866S, and P0848S, the hydrogenotrophic Methanobacteriaceae predominated (Table 2: 71.75–89.31%), whereas the PW7 biofilm had a high fraction of Acetobacterium (2.93%) and of the acetotrophic Methanosaeta (17.14%).

Figure 9.

Hydrogenotrophic microorganisms potentially contributing to MIC. Note that the acetate formed by acetogenic bacteria can be used as a carbon source by the SRB. Although the uptake of dihydrogen (H2) is suggested here, direct uptake of electrons from the steel surface by SRB and methanogens has also been suggested (Dinh et al., 2004; Enning et al., 2012).

We should point out that an acetogen pure culture, capable of deriving energy for growth from corroding iron has not yet been isolated. The suggested involvement of acetogens in corrosion thus rests on the following observations: (i) acetate production from steel upon incubation with environmental samples (Figures 2–5), (ii) the presence of acetate at the pipeline surface (Table 1: 19 ppm in PW8-PAS, higher than in the other field samples), and (iii) the high fraction of Acetobacterium at the pipeline surface compared to the other field samples (Table 2: 5.56% in PW8-PAS, but only 0–0.55% for the other samples). Except for the P0866 enrichment biofilm, the fraction of Acetobacterium was also high in the biofilm samples (Table 2: 2.93–4.86%). Acetate production by acetogens and the potential downstream effects on MIC are shown in Figure 9.

In water-transporting pipelines lacking organic carbon, the environmental role of corrosive acetogens may be to provide critical organic metabolites required. The acetate produced by acetogens through steel corrosion is used as an energy substrate by acetotrophic methanogens in present field samples. It may also be used as a carbon source by hydrogenotrophic methanogens, just as for hydrogenotrophic SRB. Incompletely-oxidizing SRB, those which oxidize lactate to acetate and CO2, are incapable of growth with only CO2 as the carbon source (Badziong et al., 1979; Rabus et al., 2006). These SRB form pyruvate from acetate and CO2 in the presence of ATP and H2 as the first step in their carbon metabolism under these conditions. The extended MIC scheme (Figure 9) indicates that the formation of acetate from CO2 by acetogens using the reducing power of iron allows these incompletely-oxidizing SRB to grow. Consequently a pipeline transporting water with little or no organic carbon, but containing bicarbonate and sulfate would still be subject to SRB-mediated corrosion, as acetate is generated at the pipeline surface. In the presence of H2 and CO2 the acetogen A. woodii can readily supply the acetate needed for the incompletely-oxidizing SRB D. vulgaris to grow on H2 and sulfate in the absence of added acetate (Figure 7). The consortium of A. woodii and D. vulgaris is somewhat more corrosive than either strain alone (Figure 8). Corrosion by D. vulgaris is co-metabolic, requiring the presence of some H2, while sulfate is present in excess (Figure 8B). The type culture A. woodii was found to be unable to produce acetate when incubated with iron coupons in an N2-CO2 atmosphere, under conditions used in Figure 8C. The differences may be more significant if, in addition to a highly corrosive Desulfovibrio ferrophilus strain IS5 (Enning et al., 2012), a highly corrosive acetogen were to be used in these studies. Future work should be directed toward the isolation of highly corrosive acetogens.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NSERC Industrial Research Chair Award to Gerrit Voordouw, which was also supported by BP America Production Co., Baker Hughes Canada, Computer Modeling Group Limited, ConocoPhillips Company, Dow Microbial Control, Enerplus Corporation, Intertek Commercial Microbiology, Oil Search (PNG) Limited, Shell Global Solutions International, Suncor Energy Inc., and Yara Norge AS, as well as by Alberta Innovates-Energy and Environment Solutions. This work was also funded by Genome Canada, Genome Alberta, the Government of Alberta and Genome BC. We are grateful for the administrative support provided by Rhonda Clark.

References

- Badziong W., Ditter B., Thauer R. K. (1979). Acetate and carbon dioxide assimilation by Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Marburg), growing on hydrogen and sulfate as sole energy source. Arch. Microbiol. 123, 301–305 10.1007/BF00406665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bihari Z., Szvetnik A., Szabó Z., Blastyák A., Zombori Z., Balás M., et al. (2011). Functional analysis of long-chain n-alkane degradation by Dietzia spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 316, 100–107 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey S. M., Park H. S., Been J., Gordon P., Sensen C. W., Voordouw G. (2008). Gene expression by the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough grown on an iron electrode under cathodic protection conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2404–2413 10.1128/AEM.02469-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey S. M., Park H. S., Voordouw J. K., He Z., Zhou J., Voordouw G. (2007). Function of periplasmic hydrogenases in the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6159–6167 10.1128/JB.00747-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callbeck C. M., Agrawal A., Voordouw G. (2013). Acetate production from oil under sulfate-reducing conditions in bioreactors injected with sulfate and nitrate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 5059–5068 10.1128/AEM.01251-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels L., Belay N., Rajagopal B. S., Weimer P. J. (1987). Bacterial methanogenesis and growth from CO2 with elemental iron as the sole source of electrons. Science 237, 509–511 10.1126/science.237.4814.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh H. T., Kuever J., Mußmann M., Hassel A. W. (2004). Iron corrosion by novel anaerobic microorganisms. Lett. Nat. 427, 829–832 10.1038/nature02321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enning D., Venzlaff H., Garrelfs J., Dinh H. T., Meyer V., Mayrhofer K., et al. (2012). Marine sulfate-reducing bacteria cause serious corrosion of iron under electroconductive biogenic mineral crust. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 1772–1787 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02778.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finster K. W., Kjeldsen K. U., Kube M., Reinhardt R., Mußmann M., Amann R., et al. (2013). Complete genome sequence of Desulfocapsa sulfexigens, a marine deltaproteobacterium specialized in disproportionating inorganic sulfur compounds. Stand. Genomic Sci. 8, 58–68 10.4056/sigs.3777412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George K., Nesic S., de Waard C. (2004). Electrochemical investigation and modeling of carbon dioxide corrosion of carbon steel in the presence of acetic acid, in NACE International, Corrosion 2004 Conference and Expo, NACE International, Paper no. 04379 (Houston, TX: ). [Google Scholar]

- Hedges B., McVeigh L. (1999). The role of acetate in CO2 corrosion: the double whammy, in NACE International Corrosion 1999 Conference and Expo, NACE International, Paper no. 21 (Houston, TX: ). [Google Scholar]

- Hu P., Rismani-Yazdi H., Stephanopoulos G. (2013). Anaerobic CO2 fixation by the acetogenic bacterium Moorella thermoacetica. AlChE J. 59, 3176–3183 10.1002/aic.14127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leang C., Ueki T., Nevin K. P., Lovley D. R. (2013). A genetic system for Clostridium ljungdahlii: a chassis for autotrophic production of biocommodities and a model homoacetogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 1102–1109 10.1128/AEM.02891-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Chen Z. Y., Guo X. P. (2008). The effect of acetic acid and acetate on CO2 corrosion of carbon steel. Anticorros. Methods Mater. 55, 130–134 10.1108/00035590810870437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. S., Chatterjee I., Dong X., Wang S.-H., Sensen C. W., Caffrey S. M., et al. (2011). Effect of sodium bisulfite injection on the microbial community composition in a brackish-water transporting pipeline. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6908–6917 10.1128/AEM.05891-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps T. J. (1991). Similarity between biotransformation rates and turnover rates of organic matter biodegradation in anaerobic environments. J. Microbiol. Methods 13, 243–254 10.1016/0167-7012(91)90061-T23763330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabus R., Hansen T. A., Widdel F. (2006). Dissimilatory sulfate- and sulfur-reducing prokaryotes, in The Prokaryotes, eds Dworkin M., Falkow S., Rosenberg E., Schleifer K.-H., Stackebrandt E. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 659–768 10.1007/0-387-30742-7_22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiel-Bengelsdorf B., Dürre P. (2012). Pathway engineering and synthetic biology using acetogens. FEBS Lett. 586, 2191–2198 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh J., Dong X., Caffrey S. M., Voordouw G., Sensen C. W. (2013). Phoenix 2: a locally installable large-scale 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis pipeline with web interface. J. Biotechnol. 167, 393–403 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub M., Demler M., Weuster-Botz D., Dürre P. (2014). Selective enhancement of autotrophic acetate production with genetically modified Acetobacterium woodii. J. Biotechnol. 178, 67–72 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suflita J. M., Phelps T. J., Little B. (2008). Carbon dioxide corrosion and acetate: a hypothesis on the influence of microorganisms. Corros. Sci. 64, 854–859 10.5006/1.3279919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trüper H. G., Schlegel H. G. (1964). Sulphur metabolism in Thiorhodaceae I. Quantitative measurements on growing cells of Chromatium okenii. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 30, 225–238 10.1007/BF02046728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Ito K., Mori K., Tsurumaru H., Harayama S. (2010). Iron-corroding methanogen isolated from a crude-oil storage tank. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 1783–1788 10.1128/AEM.00668-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]