Abstract

Aim

High-intensity interval training (HIT) results in potent metabolic adaptations in skeletal muscle, however little is known about the influence of these adaptations on energetics in vivo. We used magnetic resonance spectroscopy to examine the effects of HIT on ATP synthesis from net PCr breakdown (ATPCK), oxidative phosphorylation (ATPOX) and non-oxidative glycolysis (ATPGLY) in vivo in vastus lateralis during a 24-s maximal voluntary contraction (MVC).

Methods

Eight young men performed 6 sessions of repeated, 30-s “all-out” sprints on a cycle ergometer; measures of muscle energetics were obtained at baseline, and after the first and sixth sessions.

Results

Training increased peak oxygen consumption (35.8±1.4 to 39.3±1.6 ml·min−1·kg−1, p=0.01) and exercise capacity (217.0±11.0 to 230.5±11.7 W, p=0.04) on the ergometer, with no effects on total ATP production or force-time integral during the MVC. While ATP production by each pathway was unchanged after the first session, 6 sessions increased the relative contribution of ATPOX (from 31±2 to 39±2% of total ATP turnover, p<0.001), and lowered the relative contribution from both ATPCK (49±2 to 44±1%, p=0.004) and ATPGLY (20±2 to 17±1%, p=0.03).

Conclusion

These alterations to muscle ATP production in vivo indicate that brief, maximal contractions are performed with increased support of oxidative ATP synthesis, and relatively less contribution from anaerobic ATP production following training. These results extend previous reports of molecular and cellular adaptations to HIT and show that 6 training sessions are sufficient to alter in vivo muscle energetics, which likely contributes to increased exercise capacity after short-term HIT.

Keywords: exercise capacity, glycolysis, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, oxidative phosphorylation, phosphocreatine

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle is a malleable tissue that undergoes remodeling to accommodate the demands placed upon it. Conventional endurance training (i.e., high volume, submaximal intensity) results in increased mitochondrial content and respiratory capacity, which is accompanied by improved exercise capacity, often identified by increased whole-body maximal oxygen consumption (Holloszy 1967, Holloszy & Coyle 1984). Exercise protocols involving high-intensity interval training (HIT) on cycle ergometers also have been shown to promote metabolic adaptations and improve exercise performance (Burgomaster et al. 2005, Burgomaster et al. 2006, Burgomaster et al. 2008, Gibala et al. 2006, Harmer et al. 2000, MacDougall et al. 1998, Rodas et al. 2000, Sharp et al. 1986). Several studies have demonstrated that 6–8 weeks of sprint training elicits increased maximal activity of both glycolytic and oxidative enzymes (Jacobs et al. 1987, MacDougall et al. 1998, Nevill et al. 1989, Sharp et al. 1986). More recently, investigators have shown similar adaptations after only two weeks of HIT (Burgomaster et al. 2005, Burgomaster et al. 2006, Gibala et al. 2006, Jacobs et al. 2013, Little et al. 2010, Rodas et al. 2000). Rodas et al. (Rodas et al. 2000) reported that two weeks of a HIT protocol involving daily training in young men elicited increased creatine kinase (CK; 44%), phosphofructokinase (PFK; 106%) and citrate synthase (CS; 38%) activities in vastus lateralis (VL). These results suggest that short-term HIT is an effective strategy for rapid improvements in overall potential for ATP production in skeletal muscle.

While some evidence exists that activation of mitochondrial biogenesis (De Filippis et al. 2008, Little et al. 2011, Mathai et al. 2008) or increased capacity for oxidative phosphorylation (Fernstrom et al. 2004, Leek et al. 2001, Tonkonogi et al. 1999) may occur in response to as little as a single, exhaustive bout of exercise, the timing of exercise-induced changes in energetics of exercising muscle is unknown. Some results suggest that HIT may not promote a coordinated increase in all enzymes involved in a metabolic pathway (Burgomaster et al. 2006, MacDougall et al. 1998), while others indicate that alterations in regulation of oxidative phosphorylation may precede changes in oxidative capacity (Green et al. 2009, Layec et al. 2013, Phillips et al. 1995, Zoladz et al. 2013), which raises a question about the influence of this type of exercise training on overall pathway fluxes in vivo. In particular, there is controversy regarding the effects of sprint training on ATP pathway flux during muscular activity (Burgomaster et al. 2006, Green et al. 2009, Harmer et al. 2000, Jacobs et al. 1987, Nevill et al. 1989, Sharp et al. 1986). Based on muscle biopsies obtained immediately after exercise tests, some studies have provided evidence that sprint training leads to an increased contribution from anaerobic ATP generation during maximal muscle activity (Nevill et al. 1989, Sharp et al. 1986). In contrast, other studies have reported reduced accumulation of lactate and [H+] after sprint training, suggesting proportionally less energy provision from non-oxidative glycolytic ATP production (Burgomaster et al. 2006, Harmer et al. 2000).

While biopsy assays provide useful information about the maximal activities of specific enzymes, this approach may not accurately describe overall ATP flux through a given energetic pathway in vivo, which could explain some of the discrepancies in the literature regarding the effects of HIT. Phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) is a non-invasive technique that allows for continuous measurement of ATP synthesis through net phosphocreatine (PCr) breakdown via the CK reaction (ATPCK), glycolysis (ATPGLY) and oxidative phosphorylation (ATPOX) during muscle contractions in vivo (Kemp et al. 2001, Lanza et al. 2005, Walter et al. 1999). This approach therefore can be used to address the existing gap in the literature regarding the influence of HIT on metabolic flux through the 3 primary pathways during muscle activity in vivo.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of HIT on the bioenergetics of vastus lateralis (VL) muscle during brief, maximal voluntary contractions (MVC) in young men. Rates of ATP synthesis were measured during a 24-s MVC at baseline, 15 hr after the first HIT training session and 15 hr after the sixth training session. We hypothesized first that total ATP production through the 3 pathways would remain unchanged after the first session. Second, we hypothesized that completion of the 2-week protocol would result in a relative increase in energy supply from oxidative ATP synthesis, and reductions in the contributions from glycolysis and net PCr breakdown. The results of this study extend previous work and provide new information about skeletal muscle bioenergetics in vivo in response to short-term HIT.

METHODS

Subjects

Eight healthy men (27.0 ± 3.4 years, 176.1 ± 6.9 cm, 83.0 ± 15.4 kg; mean ± SE) volunteered to participate in the study. All participants were students at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and did not participate in any type of a regular exercise training program (i.e., no more than two bouts of 20 min twice per week). None of the participants were taking medications or dietary supplements that are known to affect muscle metabolism. First-degree relatives of type 2 diabetics were excluded from the study, to eliminate potential differences in the metabolic response to training (Kacerovsky-Bielesz et al. 2009). Participants were screened for medical history and eligibility for participating in magnetic resonance procedures. After explaining all experimental procedures and potential risks associated with the study, participants provided written informed consent before their participation. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and Yale University School of Medicine. Portions of these data have been reported elsewhere (Larsen et al. 2013).

Familiarization with Knee Extensor Force Measures

Before starting the training protocol, participants visited the laboratory to become familiarized with testing procedures and perform preliminary testing. Participants were introduced to and practiced the contraction protocol that would be used to measure VL muscle ATP production in vivo. While positioned supine, the knee of the dominant leg was fixed at 35° from straight over a custom-built apparatus with a built-in strain gauge, and the foot was fixed with a cushioned strap placed over the ankle joint, as previously described (Larsen et al. 2009, Larsen et al. 2012). To minimize hip movement and back extension during the contraction, participants were secured to the bed with a non-elastic strap placed over the hips. Participants practiced brief (3–5 s) MVCs to ensure that these contractions could be performed consistently. This setup matched the arrangement that was used for knee extensor force measurements during muscle metabolic testing in the 4 Tesla magnet at Yale University (Larsen et al. 2009).

Exercise Capacity and Peak Oxygen Consumption

Following the force measures described above, exercise capacity and peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak, ml·min−1·kg−1) were determined using an incremental exercise test to exhaustion on a friction-loaded cycle ergometer (828E, Monark, Vansbro, Sweden). The initial 2 stages of the test consisted of 2 min intervals at 60 and 120 W, and workload then was increased by 30 W every 2 min until exhaustion. Oxygen consumption was measured using an online gas collection system (TrueOne 2400, ParvoMedics, Sandy, UT) and the highest value achieved over a 15-s collection period was taken as VO2peak. Heart rate was recorded at the end of each stage, and peak workload (Wattpeak) attained during the test was recorded. Following recovery from the VO2peak test, participants also performed a 30-s sprint on the same cycle ergometer, to become familiar with the training protocol. The participants returned to the laboratory to repeat this incremental test 3 days after completing the final (sixth) training session, and exercise duration, VO2peak, and Wattpeak were recorded.

Muscle Metabolic Testing

The effects of HIT on ATP pathway flux during muscle contractions were determined using 31P-MRS, as previously described (Lanza et al. 2005, Lanza et al. 2006). Changes in intracellular phosphorus metabolites and pH were quantified and used to calculate ATPCK, ATPOX and ATPGLY during a 24-s MVC. Participants were transported to the Magnetic Resonance Research Center at Yale University where the muscle metabolic testing sessions were performed a total of 3 times: 1) at baseline (pre), 2) 15 hr after the first training session (15 hr post), and 15 hr after completing the sixth training session (2 week post). Diet was controlled for 12 hr prior to each test session. Participants were provided standardized meals with a fixed macronutrient composition (~60% carbohydrate, ~25% fat, ~15% protein) that matched estimated daily energy expenditure (Harris & Benedict 1919). In addition, participants were asked to refrain from strenuous activities (except for the training session) for 48 hr prior to each testing session. All testing sessions were performed in the morning after a standardized snack (10% of estimated daily energy expenditure) and a 10 hr overnight fast. For the remaining portion of the study, participants were instructed to maintain their regular dietary habits and physical activity routines.

All 31P-MRS measures were acquired with a probe consisting of a 6 × 8 cm 31P surface coil and a 9 cm diameter proton coil, placed over the VL. Consistent positioning of the MR probe across the 3 testing sessions was ensured by marking the probe location on the thigh with a pen. These marks were maintained by the participant throughout the study. Scout images in the axial plane were acquired to ensure optimal positioning of the VL in the isocenter of the magnet, and homogeneity of the magnetic field was optimized by localized shimming on the proton signal. Phosphorus spectra (125 µs hard pulse, nominal 60° flip angle, 2048 data points and 8000 Hz spectral width) were acquired continuously with a 2-s repetition time for 1 min of rest prior to and during each 24-s MVC, and during 10 min of recovery.

Participants were positioned supine on the patient bed of a 4.0 Tesla superconducting magnet (Bruker Biospin, Ettlingen, Germany) with the knee of the dominant leg secured to the non-magnetic exercise apparatus, as described above. To standardize conditions, participants performed 2 brief MVCs (3–5 s duration, 2 min of rest between each) prior to the first of two 24-s MVCs. Each 24-s contraction was followed by a 10-min recovery period. Participants were provided verbal encouragement and visual feedback about muscle force during all contractions. To determine force production, the voltage signal from the strain gauge was acquired and digitized at 500 Hz using customized Labview software (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). Peak force (N) and the force-time integral (FTI, Ns) were determined for each contraction using customized Matlab software (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

Spectral Analyses and Metabolite Levels

All MRS data were processed using NUTS software (Acorn NMR, Livermore, CA). Individual free induction decays (FIDs) were averaged to achieve temporal resolution of 1 min at rest, 4 s during the 24-s MVC, 8 s during the first 5 min of recovery, and 30 s during the final 5 min of recovery. The averaged FIDs for each 24-s MVC were then zero-filled and multiplied by an exponential factor corresponding to 10 Hz line-broadening before Fourier transformation to the frequency domain. Phasing and baseline-correction of the 31P spectra were performed before Lorentzian line-shapes were fit to the peaks corresponding to PCr, inorganic phosphate (Pi), phosphomonoester (PME) and γ-ATP. The average of the two trials was calculated and used for subsequent analyses.

Intracellular concentrations of phosphorus metabolites in resting skeletal muscle were determined from fully relaxed spectra (35 s repetition time, 16 averages), and based on the assumptions that total creatine = 42.5 mM, and free creatine and Pi are equal in human skeletal muscle (Harris et al. 1974, Meyer 1988). Due to rapid sampling (2 s repetition time) during the contraction protocol, corrections for partial saturation of phosphorus metabolites were applied, according to individual correction factors established by comparison of partially-saturated (2 s repetition time, 16 averages) and fully-relaxed spectra. Intracellular pH was calculated based on the chemical shift of Pi relative to PCr (Moon & Richards 1973). Adenosine diphosphate (ADP) is a potential regulator of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis, and so were calculated based on the equilibrium of the creatine kinase reaction (Veech et al. 1979):

The equilibrium constant of the CK reaction (kCK) was corrected for the effects of pH, assuming free magnesium concentration of 1 mM (Golding et al. 1995).

Calculation of ATP Flux

During the brief contraction used here, there is no net change in intracellular [ATP]. Therefore, ATP use is assumed to equal ATP production, and the latter can be calculated based on changes in PCr, Pi and pH (Kemp & Radda 1994). The contribution from each metabolic pathway to overall muscle ATP flux was calculated for each 4-s interval during the 24-s MVC. For each metabolic pathway, the highest rate of ATP synthesis observed during the contraction was taken as peak flux for that pathway, and total ATP production was calculated as the sum of all six 4-s intervals (described below).

The rate of net PCr breakdown via the CK reaction (ATPCK, mM ATP s−1) was determined at each time point from the rate of decline in PCr:

Oxidative ATP production (ATPOX, mM ATP s−1) was calculated based on the assumption that muscle oxidative capacity (Vmax) and the phosphorylation potential ([Pi][ADP]/[ATP]) regulate the rate of oxidative phosphorylation with a Km of 0.11 mM (Walter et al. 1997, Walter et al. 1999):

Use of this approach allows estimation of ATPOX based on metabolite changes at each timepoint throughout the contraction protocol.

The theoretical maximal rate of oxidative ATP production, Vmax, was calculated as the product of the rate constant of PCr recovery (kPCr) following the 24-s contraction and [PCr] in resting muscle (Larsen et al. 2009, Meyer 1988):

This calculation of the theoretical Vmax takes advantage of the linear model of respiration (Meyer 1988) and the fact that our contraction conditions were designed to avoid pronounced changes in cytosolic pH.

The initial rate of PCr resynthesis following the contraction (ViPCr) was calculated as the product of kPCr and the amount of [PCr] consumed during the contraction (Conley et al. 2000):

Production of ATP by non-oxidative glycolysis (ATPGLY, mM ATP s−1) was determined based on changes in intracellular pH, using a stoichiometry of 1.5 ATP per H+ (Crowther et al. 2002, Kemp & Radda 1994, Lanza et al. 2005, Marcinek et al. 2010), which assumes that glycogen is the primary substrate for glycolysis during maximal-intensity muscle contractions (Spriet 1989, Walter et al. 1999). Several other processes that affect intracellular [H+] were accounted for in the calculation of glycolytic ATP synthesis:

The factor m provides a correction for the protons generated by oxidative phosphorylation:

In contrast, breakdown of PCr is associated with consumption of protons, which is accounted for by the factor θ:

The β term reflects the overall proton buffering capacity of the muscle, which comprises inherent buffering capacity (βi), and buffering from bicarbonate (βCO2), inorganic phosphate (βPi), and PME (βPME) (Kemp & Radda 1994, Lanza et al. 2006, Walter et al. 1999):

where S is the solubility of CO2 (1.3 mM kPa−1) and PCO2 is 5 kPa (Walter et al. 1999)

Proton efflux rates (mM·pH unit−1·min−1) during exercise were estimated based on efflux rates calculated during recovery from the 24-s contraction (Kemp & Radda 1994, Lanza et al. 2006, Walter et al. 1999). Inherent buffering capacity was calculated from the changes in PCr and pH during the initial 4 s of the contraction, at which time glycolysis and proton efflux are assumed to have negligible effects on [H+] (Conley et al. 1998, Kemp & Radda 1994, Walter et al. 1999):

For each subsequent 4-s time point, buffering of protons was calculated by adding buffering from CO2, Pi and PME to the inherent buffering capacity:

Total production of ATP during the 24-s MVC was calculated as the sum of ATP production from each of the three metabolic pathways:

The relative contribution from each pathway during the 24-s contraction was determined at each visit by expressing ATP production from each pathway as a proportion of ATPTOTAL. The metabolic cost of contraction was calculated as the ratio of the FTI during the 24-s MVC to ATPTOTAL (N·s · mM ATP−1).

Training Protocol

The training protocol was initiated 7–14 days after the VO2peak test, and was performed on the same cycle ergometer. Six training sessions consisting of repeated 30-s bouts were performed in a 2-week time period, with a minimum of 36 hr between sessions. The number of 30-s bouts per session increased from 4 during sessions 1–2, to 5 during sessions 3–4, and finally to 6 during sessions 5–6. Each training session was initiated with a 5-min warm-up at 60 W (including two 4–5 s sprints). Participants cycled at a low, self-selected cadence against light wheel resistance during the 4-min recovery period between bouts. Prior to each 30-s bout, participants were instructed to begin pedaling as fast as possible, while one of the investigators manually adjusted the wheel tension to match 0.075 kg · (kg body mass)−1 (Burgomaster et al. 2006). Pedal revolutions were displayed on the ergometer, and recorded by camera for use in calculating power. Peak (1-s average) and mean power during each interval were calculated based on wheel resistance and number of pedal revolutions in each 30-s bout. Verbal encouragement was provided during all intervals and participants had free access to water during the recovery periods.

Statistical Analyses

The effects of training on cycling exercise duration, peak heart rate, Wattpeak, and VO2peak, each assessed at baseline and again after the 2-week protocol, were determined using Student’s paired t-tests. Mixed model, one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine changes in mean and peak power output during the training protocol, and changes across the 3 study timepoints in: metabolite concentrations and pH in resting muscle and at the end of the 24-s MVC; biochemical characteristics (Vmax, kPCr and buffer capacity); peak force and FTI from the 24-s MVC; and peak flux and relative ATP production from ATPCK, ATPGLY and ATPOX during the 24-s MVC. Post-hoc analyses were performed using pairwise comparisons, and exact p-values were reported in these cases.

At each study timepoint, changes during each 24-s MVC in energy metabolites and rates of ATP synthesis through ATPCK, ATPGLY and ATPOX were analyzed with mixed model, two-way (session, time) repeated measures ANOVAs, with time as the repeated factor. Tukey’s procedure was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons if significant session-by-time interactions were present. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. All data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Cycling Exercise Capacity and Peak Oxygen Consumption

Training increased exercise test duration and Wattpeak attained in the incremental test to exhaustion (Table 1). In addition, there was a 10 % increase in VO2peak, with no difference in peak heart rate attained during the two tests (Table 1). Mean power output per training session increased with training (p<0.001; session 1: 461 ± 33 W, session 6: 490 ± 30 W; Figure 1), indicating increased exercise capacity. In contrast, peak power output for each training session did not change as a result of training (p=0.17; session 1: 583 ± 39 W, session 6: 573 ± 33 W).

Table 1.

Cycling Exercise Performance and Peak Oxygen Consumption

| Baseline | 2 week post | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test duration (s) | 628.1 ± 44.1 | 681.8 ± 46.7 | 0.02 |

| Wattpeak (W) | 217.0 ± 11.0 | 230.5 ± 11.7 | 0.02 |

| HRpeak (beats·min−1) | 181.4 ± 3.6 | 182.3 ± 3.4 | 0.74 |

| VO2peak (ml·min−1·kg−1) | 35.8 ± 1.4 | 39.3 ± 1.6 | 0.01 |

Data are from 8 subjects and expressed as means ± SE. Wattpeak, peak workload attained during the incremental cycling test to exhaustion. HRpeak, peak heart rate. VO2peak, peak oxygen consumption.

Figure 1.

Power production during each 30-s bout of maximal effort cycling performed during the first (4 bouts) and sixth (6 bouts) training sessions. Mean power output during the 30-s cycling bouts increased with training (p < 0.001, *). Data are from 8 subjects and are presented as means ± SE.

Force Production and Metabolic Changes

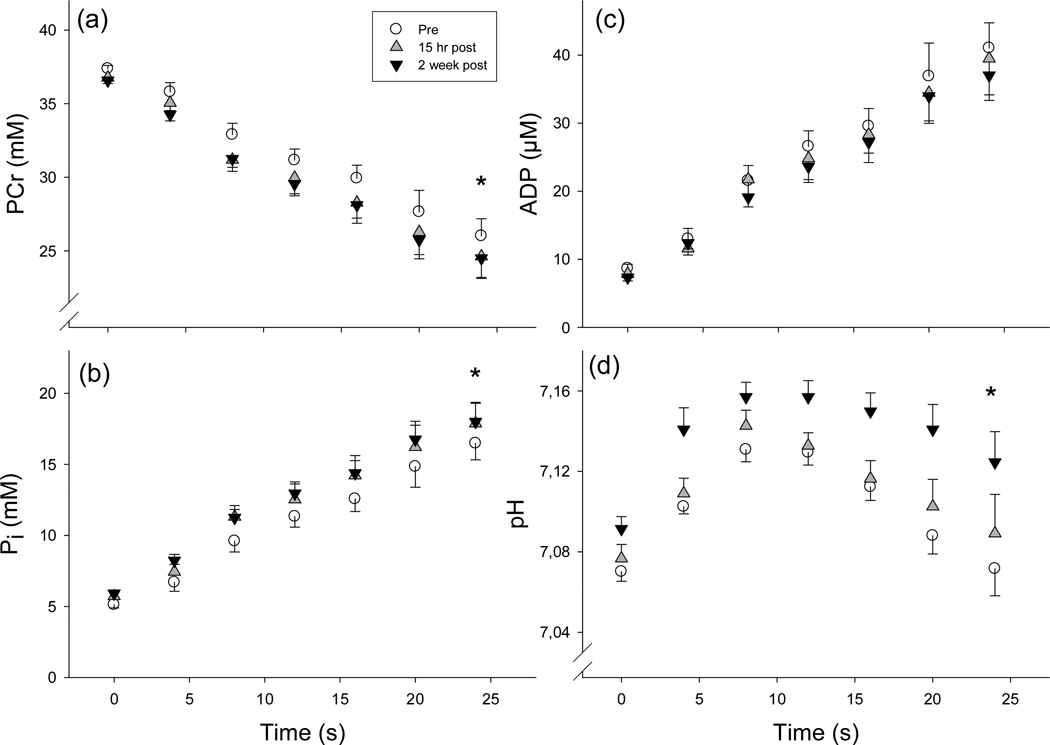

Mean force during the 24-s MVC at each of the 3 testing sessions is shown in Figure 2. There were no main effects of short-term HIT on peak force (p=0.20) or FTI (p=0.41). Metabolite concentrations and pH at rest and at the end of the MVC for each test session are provided in Table 2. Changes during the 24-s MVC in [PCr], [Pi], [ADP] and pH are shown in Figure 3. As expected, [PCr] decreased and [Pi] increased during each contraction (Ptime < 0.001, Figure 3A and 3B), and the repeated measures ANOVA indicated that [PCr] was lower and [Pi] was higher during the 24-s contraction after training (Psession < 0.001, both). The concentration of ADP increased during the contraction (Ptime <0.001, Figure 3C), with no effect of training (Psession = 0.21, Psession × time = 1.0). After a period of alkalosis at the onset of the contraction (due to PCr breakdown), intracellular pH declined toward resting levels (Ptime < 0.001, Figure 3D). Throughout the contraction, pH was higher after training (Psession < 0.001, Psession × time = 0.81, Figure 3D; Table 2). Training did not alter [PME] in resting muscle, but [PME]end was reduced after two weeks compared with baseline (p=0.003) and the first training session (p=0.04, Table 2). Cytosolic [ATP] in resting muscle was reduced after HIT (p<0.001, Table 2), as previously discussed (Larsen et al. 2013). Notably, [ATP] at the end of 24-s MVC was not different from [ATP] in resting muscle (p≥0.21), indicating that the pool of muscle adenine nucleotides were preserved during the brief contractions used here.

Figure 2.

Force traces for the 24-s maximal voluntary knee extension contraction performed before (pre), 15 hr after the first training session (15 hr post), and 15 hr after the sixth training session (2 week post), averaged every 1 s. Peak force and the force-time integral (pre: 12,014 ± 774 Ns; 15 hr post: 13,107 ± 1,045; 2 week post: 12,721 ± 1,113; p=0.41) did not change with training. Data are from 8 subjects and are expressed as means ± SE.

Table 2.

Metabolites and Muscle Bioenergetics

| Baseline (1) | 15 hr post (2) | 2 week post (3) | p-value (ANOVA) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | ||||

| PCr (mM)#* | 37.38 ± 0.22 | 36.77 ± 0.21 | 36.58 ± 0.21 | 0.001 |

| Pi (mM)#* | 5.12 ± 0.22 | 5.73 ± 0.21 | 5.92 ± 0.21 | 0.001 |

| ATP (mM)#*§ | 8.87 ± 0.33 | 6.98 ± 0.29 | 6.06 ± 0.26 | <0.001 |

| ADP (µM) | 8.67 ± 0.60 | 7.88 ± 0.58 | 7.34 ± 0.52 | 0.07 |

| PME (mM) | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.65 |

| pH*§ | 7.07 ± 0.00 | 7.08 ± 0.01 | 7.09 ± 0.01 | 0.004 |

| End of MVC | ||||

| PCr (mM)* | 26.02 ± 1.16 | 24.62 ± 1.49 | 24.50 ± 1.30 | 0.03 |

| Pi (mM)* | 16.48 ± 1.26 | 17.88 ± 1.49 | 18.00 ± 1.30 | 0.03 |

| ATP (mM)#*§ | 8.77 ± 0.48 | 6.81 ± 0.34 | 5.74 ± 0.27 | 0.002 |

| ADP (µM) | 41.03 ± 3.71 | 39.48 ± 5.31 | 37.02 ± 3.68 | 0.15 |

| PME (mM)*§ | 2.64 ± 0.36 | 2.49 ± 0.36 | 1.77 ± 0.28 | 0.02 |

| pH*§ | 7.07 ± 0.01 | 7.09 ± 0.02 | 7.12 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Oxidative Capacity | ||||

| kPCr (s−1)*§ | 0.029 ± 0.001 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 0.033 ± 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Vmax (mM· min−1)*§ | 64.70 ± 2.97 | 61.31 ± 3.58 | 71.46 ± 3.12 | 0.02 |

| ViPCr (mM·min−1)* | 19.42 ± 1.53 | 19.79 ± 1.49 | 23.47 ± 2.43 | 0.006 |

Data are from 8 subjects and expressed as means ± SE.

Significant (p<0.05) differences between testing sessions 1 and 2 (#), 1 and 3 (*), and 2 and 3 (§) are indicated.

kPCr, rate constant for PCr resynthesis. Vmax, maximal rate of oxidative ATP synthesis. ViPCr, initial rate of PCr resynthesis.

Figure 3.

Changes in phosphocreatine (PCr, A), inorganic phosphate (Pi, B), adenosine diphosphate (ADP, C) and pH (D) during the 24-s maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) before (pre), 15 hr after the first training session (15 hr post), and 15 hr after the sixth training session (2 week post). Training resulted in lower [PCr] and higher [Pi] during the 24-s MVC (psession < 0.001, *), with no effect on [ADP]. Throughout the contraction, intracellular pH was higher after training (psession < 0.001, *). Data are from 8 subjects and are presented as means ± SE.

Muscle Metabolic Characteristics and ATP Synthesis

Both the rate of PCr recovery (kPCr, p = 0.001) following the MVC and muscle oxidative capacity (Vmax, p = 0.004) were increased after the sixth training session compared with baseline, with no change after the first session compared with baseline. Proton buffering capacity did not change after the first (31.0 ± 5.9 slykes) or sixth (26.2 ± 5.0) training sessions, compared with baseline (26.2 ± 3.6, p = 0.71). As expected, proton efflux rates were negligible during the 24-s MVC. Rates of ATP synthesis through ATPCK, ATPGLY and ATPOX are shown in Figure 4. As expected, the rate of net PCr breakdown slowed during the 24-s contraction after reaching a peak at ~8 s (Ptime < 0.001, Figure 4A). There was no effect of training on overall ATPCK during the contraction (Psession = 0.96, Psession × time = 0.88). Glycolytic flux gradually increased during the 24-s MVC with a peak at ~20 s (Ptime < 0.001, Figure 4B), with no effect of training on total ATPGLY (Psession = 0.45, Psession × time = 0.96). Rates of ATP synthesis from oxidative phosphorylation increased from the onset of the 24-s MVC (Ptime < 0.001, Figure 4C), and overall, ATPOX increased following training (Psession < 0.001, Psession × time = 0.32). Total ATP synthesis increased during the 24-s MVC (Ptime < 0.001, Figure 4D), but did not differ across the three testing sessions (Psession = 0.62, Psession × time = 0.98).

Figure 4.

Rates of ATP synthesis during a 24-s maximal voluntary knee extension contraction (MVC) before (pre), 15 hr after the first training session (15 hr post), and 15 hr (2 week post) after the sixth training session. ATP provision from net breakdown of phosphocreatine (A, ATPCK) and glycolysis (B, ATPGLY) was similar across the three testing sessions (psession ≥ 0.45). Oxidative ATP synthesis (C, ATPOX) increased with training (psession < 0.001, *). Total ATP production (D, ATPTOTAL) during the 24-s MVC was not different across the 3 testing sessions (psession = 0.62). Data are from 8 subjects and are presented as means ± SE.

During the 24-s MVC, peak fluxes through the CK reaction (p = 0.50) and glycolysis (p = 0.09) were unchanged by training. Peak ATPOX increased with training (p = 0.004), such that the peak rate of oxidative ATP synthesis was higher after two weeks compared with baseline (p = 0.002) and after the first training session (p = 0.008). Similarly, the initial rate of PCr recovery (ViPCr) increased with training (p = 0.006, Table 2), such that ViPCr was higher after two weeks compared with baseline (p = 0.01), with no change after the first session compared with baseline.

The sum of ATP production through each pathway for the entire 24-s contraction is shown in Figure 5A. When ATP production from each pathway was expressed relative to ATPTOTAL for each individual, the first training session had no effect on ATP provision from each of the three pathways (p ≤ 0.13), Figure 5B. After 6 training sessions, however, the relative contribution from ATPCK (49 ± 2 vs. 44 ± 1% of total ATP turnover, p = 0.004) and ATPGLY (20 ± 2 vs. 17 ± 1%, p = 0.03) decreased, while the proportion of energy derived from ATPOX increased (31 ± 2 vs. 39 ± 2%, p < 0.001). The metabolic cost of contraction (pre: 471.4 ± 47.2 N·s·mM ATP−1; 15 hr post: 493.0 ± 39.5; 2 week post: 466.1 ± 40.0, p = 0.46) did not vary across testing sessions, suggesting that metabolic economy was not altered by short-term HIT.

Figure 5.

Total (A) and relative (B) contribution to ATP production from net breakdown of phosphocreatine via the creatine kinase reaction (CK), glycolysis (GLY), and oxidative phosphorylation (OX) during the entire 24-s maximal voluntary contraction before (pre), 15 hr after the first training session (15 hr post), and 15 hr after the sixth training session (2 week post). After 2 weeks, total and relative contribution of ATP production from OX (p < 0.001, *) increased, while the relative proportion of ATP derived from CK (p = 0.004, *) and GLY (p = 0.03, *) decreased. Data are from 8 subjects and expressed as means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that short-term HIT not only increased VO2peak and whole-body work capacity, but also altered skeletal muscle ATP flux in vivo during maximal-intensity contractions, such that a greater proportion of total ATP turnover was supported via aerobic metabolism. Using 31P-MRS, we showed that, while 6 training sessions had no effect on force production and overall ATP synthesis during the 24-s MVC, oxidative ATP production increased and the relative contributions from net PCr breakdown and non-oxidative glycolysis decreased. These rapid adaptations in skeletal muscle bioenergetics were consistent with the observed increase in muscle oxidative capacity. Notably, a single training session had no effect on the bioenergetic response to a 24-s MVC. Overall, these results extend recent reports of increased mitochondrial capacity following HIT to the in vivo condition, and demonstrate the contribution of intramuscular bioenergetic adaptations to improved whole-body exercise performance observed after short-term sprint training.

Whole-Body Exercise Capacity and Peak Oxygen Consumption

The ability to sustain power output during the repeated 30-s bouts of cycling increased with training (Figure 1), consistent with previous results (Forbes et al. 2008) and indicating greater fatigue resistance and enhanced exercise capacity after 6 sessions of HIT. Further, the increase in exercise capacity observed here was accompanied by an ~10% increase in VO2peak, consistent with some (Rodas et al. 2000) but not all (Burgomaster et al. 2005, Burgomaster et al. 2006) studies employing short-term HIT. Several studies also have demonstrated improved exercise performance, such as faster cycling time trials and increased time to exhaustion during cycling at submaximal workload, after 6 sessions of HIT (Burgomaster et al. 2005, Burgomaster et al. 2006, Gibala et al. 2006). In some cases, increased endurance capacity was observed in the absence of increased whole-body aerobic capacity (Burgomaster et al. 2005, Burgomaster et al. 2006), suggesting that peripheral adaptations played an important role in the rapid improvements in exercise performance following short-term HIT (Burgomaster et al. 2005). This interpretation is well supported by the results of the current study, where increases in cycling endurance capacity, VO2peak and in vivo muscle oxidative capacity ranged from ~9–14% and highlight the prominent role of muscle mitochondrial adaptations in the overall response to short-term HIT.

Relative ATP Provision from Anaerobic and Aerobic Pathways

To evaluate the contribution of each metabolic pathway during a maximal contraction, we expressed ATP production by each pathway relative to overall ATP production during the MVC. At baseline, the majority of ATP provision for the 24-s MVC was derived from net PCr breakdown (~50%), with smaller contributions from glycolysis (~20%) and oxidative ATP synthesis (~30%), Figure 5B. Thus, this 24-s protocol provided an opportunity to examine the effects of short term HIT on bioenergetics early during muscle activity, prior to the development of fatigue. The relative contributions from each pathway during the 24s MVC were similar to estimates from biopsy studies suggesting that 70% of energy provision for a 30-s all out sprint was supplied via anaerobic metabolism (Bogdanis et al. 1996, Parolin et al. 1999, Putman et al. 1995). The relative ATP production by each pathway was unchanged after the first training session. In contrast, 6 sessions of HIT resulted in an increased proportion of ATP derived from oxidative phosphorylation, while the contributions from net PCr breakdown and glycolysis declined (Figure 5B). Our results are consistent with previous observations of increased mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation and reduced lactate accumulation during matched-work cycling following 6 sessions of HIT (Burgomaster et al. 2006). Collectively, these results suggest that short-term HIT promotes better matching between glycolytic flux and oxidative ATP production.

Muscle Oxidative ATP Production

As expected, the rate of oxidative ATP synthesis increased continuously during each 24-s MVC (Figure 4C). For the first time, we show that this increase in oxidative ATP production is more rapid following HIT (Figure 4C, Figure 5A). Notably, both peak oxidative ATP flux and the initial rate of PCr resynthesis were higher after training (Table 2). Our results are consistent with observations from studies showing that short term HIT resulted in speeding of pulmonary O2 uptake (VO2p) kinetics, reflecting muscle O2 use, at the onset of muscle activity (McKay et al. 2009, Williams et al. 2013). Endurance training has been shown to increase muscle’s sensitivity to putative regulators (e.g., [ADP], [Pi]) of oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle, such that a higher rate of respiration is achieved with the same metabolic disturbance in the cell (Dudley et al. 1987, Kent-Braun et al. 1990). By normalizing muscle oxygen consumption to content of cytochrome C, Dudley and colleagues (Dudley et al. 1987) showed that the muscle’s improved sensitivity of respiratory control likewise could be attributed to increased mitochondrial content. Consistent with these results, we showed that greater rates of oxidative ATP production at the onset of muscle activity and immediately following the contraction (ViPCr) were accomplished with no change in [ADP] but increased kPCr and Vmax. Hence, the increased in vivo oxidative capacity may have been accompanied by an improved sensitivity of oxidative phosphorylation for ADP, presumably due to increased mitochondrial content. Indeed, Jacobs et al. (Jacobs et al. 2013) recently demonstrated increased muscle respiratory capacity after 2 weeks of HIT that coincided with a corresponding increase in mitochondrial content. We do note, that although [ADP] was unchanged by HIT, [Pi] was elevated at the end of the contraction following training; its potential impact on increased mitochondrial respiration is discussed below. Overall, our results extend previous reports to show that short term HIT, in addition to increasing in vivo oxidative capacity, promotes greater oxidative ATP production during maximal voluntary contractions.

Recently, several investigators have provided evidence to suggest that mitochondrial biogenesis may be initiated as early as after a single bout of exercise (De Filippis et al. 2008, Little et al. 2011, Mathai et al. 2008). Little et al. (Little et al. 2011) showed that a single session of HIT enhanced signaling for mitochondrial biogenesis and increased mitochondrial protein content. In addition, a single, exhaustive bout of exercise has also been reported to increase maximal activity of CS and respiratory capacity of skinned muscle fibers (Fernstrom et al. 2004, Leek et al. 2001, Tonkonogi et al. 1999). In the present study, however, there were no changes in oxidative ATP production during the 24-s MVC (Figure 5), ViPCr (Table 2), nor in the capacity for oxidative phosphorylation in vivo 15 hours after the first training session (Larsen et al. 2013). Thus, our results indicate that more than a single bout of HIT is required to promote metabolic adaptations that enhance in vivo oxidative ATP production in human skeletal muscle.

Notably, several training studies have provided some evidence indicating that regulation of muscle oxidative metabolism may be altered before any apparent changes in mitochondrial capacity (Green et al. 2009, Layec et al. 2013, Phillips et al. 1995, Zoladz et al. 2013). Phillips et al. (Phillips et al. 1995) found speeding of VO2p kinetics after only 4 days of endurance training, while an increase in CS activity was not evident before completion of 30 training sessions, suggesting that adaptations other than increased mitochondrial content may influence regulation of muscle oxidative metabolism in the early response to training. Substrate availability for the electron transport chain has been suggested as a possible explanation for faster activation of oxidative phosphorylation after exercise training (Poole et al. 2008). While both [ADP] and [Pi] increased throughout each contraction in the present study (Figure 3), only [Pi] increased after training (Figure 3), suggesting that elevated [Pi] may have elicited greater stimulation of oxidative phosphorylation, and thus contributed to higher rates of oxidative ATP synthesis, after HIT. This interpretation is consistent with results from a recent study by Schmitz et al. (Schmitz et al. 2012) indicating the importance of Pi in regulation of in vivo mitochondrial ATP synthesis in skeletal muscle. Despite similar time course and magnitude of change for oxidative ATP production during contraction and recovery, different mechanisms may be responsible for changes in these measures of muscle oxidative metabolism after HIT. For example, there is good evidence to suggest that O2 availability limits oxidative phosphorylation during exercise (Poole et al. 2008), while PCr recovery in untrained individuals (as used here), has been shown to be limited by intrinsic mitochondrial capacity and not O2 availability (Haseler et al. 2004).

Lower [PCr] at rest and throughout the contraction (Table 2) may also have contributed to faster activation of oxidative phosphorylation and higher rates of oxidative ATP synthesis after training. Several studies have provided evidence indicating that [PCr] directly influences the regulation of oxidative phosphorylation (Glancy et al. 2008, Walsh et al. 2001). In a study of isolated mitochondria, Glancy and colleagues (Glancy et al. 2008) reported a linear relationship between the rate constant of mitochondrial respiration and total creatine (PCr + Cr), such that lower content of total creatine was accompanied by a faster rate of mitochondrial respiration. Similarly, Walsh et al. (Walsh et al. 2001) showed that, in permeabilised skeletal muscle fibers, [PCr] attenuated the sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to ADP. These results corroborate Meyer’s electric analog model of respiratory control, in which the total creatine pool (i.e., PCr + Cr) serves as a metabolic capacitor (Meyer 1988). Notably, while [PCr] and [Pi] were altered even after the first training session, there were no changes in oxidative ATP production or the rate of PCr recovery at that time point, suggesting that the magnitude of change in these intracellular metabolites was not sufficient to affect oxidative ATP production. Collectively, our results showed that short term HIT resulted in increased oxidative ATP production during short, intense bursts of muscle activity, presumably as a result of greater muscle oxidative capacity, and possibly accentuated by lower cytosolic [PCr] and higher [Pi].

Muscle Glycolytic ATP Production

In addition to increasing the capacity for oxidative metabolism, sprint training has been shown to increase activities of key enzymes involved in glycolysis, suggesting an improved potential for glycolytic ATP synthesis (Jacobs et al. 1987, MacDougall et al. 1998, Rodas et al. 2000, Sharp et al. 1986). We found that neither a single nor 6 training sessions elicited increased absolute rates of glycolytic ATP production (Figure 4B; Figure 5) or peak glycolytic flux during the 24-s MVC. It is important to bear in mind that the 24-s contraction used here likely did not maximally activate glycolysis. Our protocol was designed to examine functional rates of glycolytic ATP production in vivo during maximal-intensity muscle contractions, rather than to quantify maximal capacity for glycolytic flux, per se. It is reasonable to expect that the increased oxidative capacity in response to training provided better matching not only between total energy demand and oxidative flux, but also between glycolytic production of substrates for the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the capacity to use these.

The concentration of PME, which consists mainly of glucose-6-phosphate (Kemp et al. 2001, Walter et al. 1999), increased from rest to the end of each 24-s MVC (Table 2), as previously reported for maximal-intensity muscle contractions (Lanza et al. 2005, Lanza et al. 2006, Walter et al. 1999). The magnitude of the increase in [PME] during the MVC was lower after 2 weeks of training. Similarly, Green et al. (Green et al. 2009) showed that 5 days of traditional endurance training reduced the accumulation of several glycolytic intermediates (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate) during submaximal cycling. As buildup of PME occurs when glycogen phosphorylase activity exceeds activity of the rate-limiting enzyme, PFK, our results suggest that 2 weeks of HIT resulted in a better matching of fluxes through glycogen phosphorylase and PFK during a maximal contraction.

By design, the 24-s contraction was sufficiently short so as to avoid significant intracellular acidosis, which could slow enzyme kinetics and affect our muscle oxidative capacity and flux measures. Notably, training had an overall effect on pH such that it was higher at rest and during the 24-s MVC after training (Table 2, Figure 3D). Several factors influence intracellular proton balance during muscle activity. Breakdown of PCr via the CK reaction consumes H+ and explains the initial alkalosis during the 24-s MVC (Figure 3D). In contrast, during contraction non-oxidative glycolysis contributes to H+ accumulation and the consequent decrease in intracellular pH. Finally, cytosolic pH also is influenced by proton buffering capacity and proton efflux rates. We observed no effect of HIT on buffering capacity, efflux rates or absolute rates of PCr breakdown or glycolysis during the contraction, suggesting that these factors did not contribute to the overall changes in alkalosis after HIT. Thus, the source and physiological significance of the small shift toward a more alkalotic pH following HIT are not clear at this time.

ATP Provision via Net PCr Breakdown

Breakdown of PCr plays an important role for supplying ATP, particularly during the initial portion of high-intensity muscle activity, as illustrated in Figure 4A. Using serial biopsy samples, Barnett et al. (Barnett et al. 2004) showed that 8 weeks of sprint training resulted in an increased rate of PCr consumption during an ”all-out” 30-s sprint, which is consistent with the results from Rodas and colleagues (Rodas et al. 2000) who showed a 44% increase in CK activity after 2 weeks of sprint training. In contrast to these findings from biopsy studies, we observed no effects of training on total or peak ATP production from net PCr breakdown in vivo (Figure 5A). Notably, the higher rates of oxidative ATP synthesis in the present study would be expected to reduce PCr consumption during the contraction (Figure 5), and thus mitigate the net breakdown of PCr.

In summary, we have shown that short-term HIT increased cycling exercise capacity and VO2peak, and was accompanied by altered skeletal muscle energetics in vivo. In addition to an increase in muscle oxidative capacity, the absolute and relative rates of oxidative ATP production during a short, maximal-intensity contraction increased after 2 weeks of training. Thus, ATP production from oxidative phosphorylation was relatively greater, and that from the CK reaction and glycolysis relatively lower after training. These results provide novel information regarding the time course in vivo for changes in muscle energetics as a result of short term HIT, and extend observations from previous studies to suggest that greater support from aerobic metabolism and less reliance on non-oxidative ATP production likely contribute to improved exercise capacity after short-term HIT.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their enthusiasm and perseverance throughout the study. We also wish to thank John Buonaccorsi, Ph.D. for statistical advice, Douglas Befroy, D.Phil., and members of the Muscle Physiology Laboratory for help with various aspects of the project. This work was supported by NIH/NIA K02 AG023582, the Keck Foundation and a University of Massachusetts Amherst Graduate School Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are reported by the authors.

References

- Barnett C, Carey M, Proietto J, Cerin E, Febbraio MA, Jenkins D. Muscle metabolism during sprint exercise in man: influence of sprint training. J.Sci.Med.Sport. 2004;7:314–322. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanis GC, Nevill ME, Boobis LH, Lakomy HK. Contribution of phosphocreatine and aerobic metabolism to energy supply during repeated sprint exercise. J.Appl.Physiol. 1996;80:876–884. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.3.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgomaster KA, Heigenhauser GJ, Gibala MJ. Effect of short-term sprint interval training on human skeletal muscle carbohydrate metabolism during exercise and time-trial performance. J.Appl.Physiol. 2006;100:2041–2047. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01220.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgomaster KA, Howarth KR, Phillips SM, Rakobowchuk M, Macdonald MJ, McGee SL, Gibala MJ. Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans. J.Physiol. 2008;586:151–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgomaster KA, Hughes SC, Heigenhauser GJ, Bradwell SN, Gibala MJ. Six sessions of sprint interval training increases muscle oxidative potential and cycle endurance capacity in humans. J.Appl.Physiol. 2005;98:1985–1990. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01095.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Esselman PC. Oxidative capacity and ageing in human muscle. Journal of Physiology-London. 2000;526:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Kushmerick MJ, Jubrias SA. Glycolysis is independent of oxygenation state in stimulated human skeletal muscle in vivo. J.Physiol. 1998;511(Pt 3):935–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.935bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther GJ, Jubrias SA, Gronka RK, Conley KE. A "functional biopsy" of muscle properties in sprinters and distance runners. Med.Sci.Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1719–1724. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200211000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis E, Alvarez G, Berria R, Cusi K, Everman S, Meyer C, Mandarino LJ. Insulin-resistant muscle is exercise resistant: evidence for reduced response of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes to exercise. Am.J.Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2008;294:E607–E614. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00729.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley GA, Tullson PC, Terjung RL. Influence of mitochondrial content on the sensitivity of respiratory control. J.Biol.Chem. 1987;262:9109–9114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrom M, Tonkonogi M, Sahlin K. Effects of acute and chronic endurance exercise on mitochondrial uncoupling in human skeletal muscle. J.Physiol. 2004;554:755–763. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SC, Slade JM, Meyer RA. Short-term high-intensity interval training improves phosphocreatine recovery kinetics following moderate-intensity exercise in humans. Appl.Physiol Nutr.Metab. 2008;33:1124–1131. doi: 10.1139/H08-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibala MJ, Little JP, van Essen M, Wilkin GP, Burgomaster KA, Safdar A, Raha S, Tarnopolsky MA. Short-term sprint interval versus traditional endurance training: similar initial adaptations in human skeletal muscle and exercise performance. J.Physiol. 2006;575:901–911. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glancy B, Barstow T, Willis WT. Linear relation between time constant of oxygen uptake kinetics, total creatine, and mitochondrial content in vitro. Am.J.Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C79–C87. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00138.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding EM, Teague WE, Jr, Dobson GP. Adjustment of K' to varying pH and pMg for the creatine kinase, adenylate kinase and ATP hydrolysis equilibria permitting quantitative bioenergetic assessment. J.Exp.Biol. 1995;198:1775–1782. doi: 10.1242/jeb.198.8.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green HJ, Bombardier E, Burnett ME, Smith IC, Tupling SM, Ranney DA. Time-dependent effects of short-term training on muscle metabolism during the early phase of exercise. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1383–R1391. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00203.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer AR, McKenna MJ, Sutton JR, Snow RJ, Ruell PA, Booth J, Thompson MW, Mackay NA, Stathis CG, Crameri RM, Carey MF, Eager DM. Skeletal muscle metabolic and ionic adaptations during intense exercise following sprint training in humans. J.Appl.Physiol. 2000;89:1793–1803. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Benedict F. A biometric study of basal metabolism in man. Washington D C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Harris RC, Hultman E, Nordesjo LO. Glycogen, glycolytic intermediates and high-energy phosphates determined in biopsy samples of musculus quadriceps femoris of man at rest. Methods and variance of values. Scand.J.Clin.Lab Invest. 1974;33:109–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseler LJ, Lin AP, Richardson RS. Skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism in sedentary humans: 31P-MRS assessment of O2 supply and demand limitations. J.Appl.Physiol. 2004;97:1077–1081. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01321.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J.Biol.Chem. 1967;242:2278–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO, Coyle EF. Adaptations of skeletal muscle to endurance exercise and their metabolic consequences. J.Appl.Physiol. 1984;56:831–838. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.4.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs I, Esbjornsson M, Sylven C, Holm I, Jansson E. Sprint training effects on muscle myoglobin, enzymes, fiber types, and blood lactate. Med.Sci.Sports Exerc. 1987;19:368–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RA, Fluck D, Bonne TC, Burgi S, Christensen PM, Toigo M, Lundby C. Improvements in exercise performance with high-intensity interval training coincide with an increase in skeletal muscle mitochondrial content and function. J.Appl.Physiol (1985.) 2013;115:785–793. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00445.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacerovsky-Bielesz G, Chmelik M, Ling C, Pokan R, Szendroedi J, Farukuoye M, Kacerovsky M, Schmid AI, Gruber S, Wolzt M, Moser E, Pacini G, Smekal G, Groop L, Roden M. Short-term exercise training does not stimulate skeletal muscle ATP synthesis in relatives of humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:1333–1341. doi: 10.2337/db08-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp GJ, Radda GK. Quantitative interpretation of bioenergetic data from 31P and 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic studies of skeletal muscle: an analytical review. Magn Reson.Q. 1994;10:43–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp GJ, Roussel M, Bendahan D, Le Fur Y, Cozzone PJ. Interrelations of ATP synthesis and proton handling in ischaemically exercising human forearm muscle studied by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J.Physiol. 2001;535:901–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent-Braun JA, McCully KK, Chance B. Metabolic effects of training in humans: a 31P-MRS study. J.Appl.Physiol. 1990;69:1165–1170. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.3.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Befroy DE, Kent-Braun JA. Age-related changes in ATP-producing pathways in human skeletal muscle in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99:1736–1744. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00566.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Wigmore DM, Befroy DE, Kent-Braun JA. In vivo ATP production during free-flow and ischaemic muscle contractions in humans. J.Physiol. 2006;577:353–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RG, Befroy DE, Kent-Braun JA. High-intensity interval training increases in vivo oxidative capacity with no effect on P(i)-->ATP rate in resting human muscle. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R333–R342. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00409.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RG, Callahan DM, Foulis SA, Kent-Braun JA. In vivo oxidative capacity varies with muscle and training status in young adults. J.Appl.Physiol. 2009;107:873–879. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00260.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RG, Callahan DM, Foulis SA, Kent-Braun JA. Age-related changes in oxidative capacity differ between locomotory muscles and are associated with physical activity behavior. Appl.Physiol Nutr.Metab. 2012;37:88–99. doi: 10.1139/h11-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layec G, Haseler LJ, Hoff J, Hart CR, Liu X, Le Fur Y, Jeong EK, Richardson RS. Short-term training alters the control of mitochondrial respiration rate before maximal oxidative ATP synthesis. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2013;208:376–386. doi: 10.1111/apha.12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek BT, Mudaliar SR, Henry R, Mathieu-Costello O, Richardson RS. Effect of acute exercise on citrate synthase activity in untrained and trained human skeletal muscle. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R441–R447. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.2.R441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JP, Safdar A, Bishop D, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. An acute bout of high-intensity interval training increases the nuclear abundance of PGC-1alpha and activates mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R1303–R1310. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00538.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JP, Safdar A, Wilkin GP, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. A practical model of low-volume high-intensity interval training induces mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle: potential mechanisms. J.Physiol. 2010;588:1011–1022. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall JD, Hicks AL, MacDonald JR, McKelvie RS, Green HJ, Smith KM. Muscle performance and enzymatic adaptations to sprint interval training. J.Appl.Physiol. 1998;84:2138–2142. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.6.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinek DJ, Kushmerick MJ, Conley KE. Lactic acidosis in vivo: testing the link between lactate generation and H+ accumulation in ischemic mouse muscle. J.Appl.Physiol. 2010;108:1479–1486. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01189.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathai AS, Bonen A, Benton CR, Robinson DL, Graham TE. Rapid exercise-induced changes in PGC-1alpha mRNA and protein in human skeletal muscle. J.Appl.Physiol. 2008;105:1098–1105. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay BR, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. Effect of short-term high-intensity interval training vs. continuous training on O2 uptake kinetics, muscle deoxygenation, and exercise performance. J.Appl.Physiol (1985.) 2009;107:128–138. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90828.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA. A Linear-Model of Muscle Respiration Explains Monoexponential Phosphocreatine Changes. American Journal of Physiology. 1988;254:C548–C553. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.4.C548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RB, Richards JH. Determination of intracellular pH by 31P magnetic resonance. J.Biol.Chem. 1973;248:7276–7278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevill ME, Boobis LH, Brooks S, Williams C. Effect of training on muscle metabolism during treadmill sprinting. J.Appl.Physiol. 1989;67:2376–2382. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.6.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolin ML, Chesley A, Matsos MP, Spriet LL, Jones NL, Heigenhauser GJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle glycogen phosphorylase and PDH during maximal intermittent exercise. Am.J.Physiol. 1999;277:E890–E900. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.5.E890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SM, Green HJ, Macdonald MJ, Hughson RL. Progressive effect of endurance training on VO2 kinetics at the onset of submaximal exercise. J.Appl.Physiol (1985.) 1995;79:1914–1920. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.6.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole DC, Barstow TJ, McDonough P, Jones AM. Control of oxygen uptake during exercise. Med.Sci.Sports Exerc. 2008;40:462–474. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815ef29b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putman CT, Jones NL, Lands LC, Bragg TM, Hollidge-Horvat MG, Heigenhauser GJ. Skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase activity during maximal exercise in humans. Am.J.Physiol. 1995;269:E458–E468. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.3.E458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodas G, Ventura JL, Cadefau JA, Cusso R, Parra J. A short training programme for the rapid improvement of both aerobic and anaerobic metabolism. Eur.J.Appl.Physiol. 2000;82:480–486. doi: 10.1007/s004210000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JP, Jeneson JA, van Oorschot JW, Prompers JJ, Nicolay K, Hilbers PA, van Riel NA. Prediction of muscle energy states at low metabolic rates requires feedback control of mitochondrial respiratory chain activity by inorganic phosphate. PLoS.One. 2012;7:e34118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp RL, Costill DL, Fink WJ, King DS. Effects of eight weeks of bicycle ergometer sprint training on human muscle buffer capacity. Int.J.Sports Med. 1986;7:13–17. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriet LL. ATP utilization and provision in fast-twitch skeletal muscle during tetanic contractions. Am.J.Physiol. 1989;257:E595–E605. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.257.4.E595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkonogi M, Walsh B, Tiivel T, Saks V, Sahlin K. Mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle is not impaired by high intensity exercise. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437:562–568. doi: 10.1007/s004240050818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veech RL, Lawson JW, Cornell NW, Krebs HA. Cytosolic phosphorylation potential. J.Biol.Chem. 1979;254:6538–6547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh B, Tonkonogi M, Soderlund K, Hultman E, Saks V, Sahlin K. The role of phosphorylcreatine and creatine in the regulation of mitochondrial respiration in human skeletal muscle. J.Physiol. 2001;537:971–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter G, Vandenborne K, Elliott M, Leigh JS. In vivo ATP synthesis rates in single human muscles during high intensity exercise. J.Physiol. 1999;519(Pt 3):901–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0901n.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter G, Vandenborne K, McCully KK, Leigh JS. Noninvasive measurement of phosphocreatine recovery kinetics in single human muscles. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 1997;41:C525–C534. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. High-intensity interval training speeds the adjustment of pulmonary O2 uptake, but not muscle deoxygenation, during moderate-intensity exercise transitions initiated from low and elevated baseline metabolic rates. J.Appl.Physiol (1985.) 2013;114:1550–1562. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00575.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoladz JA, Grassi B, Majerczak J, Szkutnik Z, Korostynski M, Karasinski J, Kilarski W, Korzeniewski B. Training-induced acceleration of O(2) uptake on-kinetics precedes muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in humans. Exp.Physiol. 2013;98:883–898. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]