Abstract

We incorporate anthropological insights into a stigma framework to elucidate the role of culture in threat perception and stigma among Chinese groups. Prior work suggests that genetic contamination that jeopardizes the extension of one’s family lineage may comprise a culture-specific threat among Chinese groups. In Study 1, a national survey conducted from 2002–2003 assessed cultural differences in mental illness stigma and perceptions of threat in 56 Chinese-Americans and 589 European-Americans. Study 2 sought to empirically test this culture-specific threat of genetic contamination to lineage via a memory paradigm. Conducted from June to August 2010, 48 Chinese-American and 37 European-American university students in New York City read vignettes containing content referring to lineage or non-lineage concerns. Half the participants in each ethnic group were assigned to a condition in which the illness was likely to be inherited (genetic condition) and the rest read that the illness was unlikely to be inherited (non-genetic condition). Findings from Study 1 and 2 were convergent. In Study 1, culture-specific threat to lineage predicted cultural variation in stigma independently and after accounting for other forms of threat. In Study 2, Chinese-Americans in the genetic condition were more likely to accurately recall and recognize lineage content than the Chinese-Americans in the non-genetic condition, but that memorial pattern was not found for non-lineage content. The identification of this culture-specific threat among Chinese groups has direct implications for culturally-tailored anti-stigma interventions. Further, this framework might be implemented across other conditions and cultural groups to reduce stigma across cultures.

Keywords: Chinesem, Stigma, Attitudes, Mental Illness, Social Cognition, Culture, Threat, Stereotypes

“Chinese people say, ‘If she is crazy and not yet married, and if you tell others she is sick, no one will marry her.’ This person is someone who has no future. It’s as if she has died.”

– Chinese Immigrant Sister of individual with schizophrenia

Mental illness stigma has been described as especially pervasive and severe in Chinese groups (Yang & Kleinman, 2008). Chinese groups have consistently endorsed more severe negative stereotypes and social restriction towards people with mental illness (Yang, 2007). Such intensified stigma results in damaging internalization of stereotypes, concealment of illness, and other harmful psychological outcomes (Lee, 2005). Stigma threatens adherence to treatment and makes sustained reintegration into society difficult (Lee et al., 2006). Yet the cultural mechanisms that underlie the heightened mental illness stigma among Chinese groups when compared with Western groups (Yang, 2007) remain unexamined. We utilize cultural anthropological insights into Chinese society to identify and empirically test cultural constructs that may explain these group differences. Specifically, we assess whether the extension of one’s family lineage through marriage and making it prosper in perpetuity (Kleinman & Kleinman, 1993) represents such a novel mechanism. We examine this via two studies offering different methodological strengths—a national vignette study and a laboratory experiment.

Mental Illness Stigma Framework

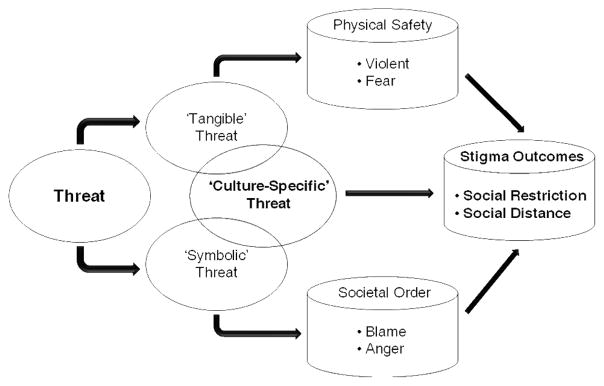

Goffman (1963, p. 3) proposes that the stigmatized person is reduced “from a whole” person to a “tainted, discounted one.” People in a given social context may attach negative stereotypes to mental illness that may differ from the actual characteristics of a person, of which dangerousness is considered central (Jones et al., 1984). The present research builds on a motivational framework that assumes that accurate perception of potential threat is inherent to survival (Stangor & Crandall, 2000). Mental illness stigma accordingly develops from a universally-held motivation to avoid danger that manifests through two distinct sources of threat (see non-highlighted portions of Figure 1). The first—an instrumental, ‘tangible threat’ to individuals—“threatens a material or concrete good, such as health and safety” (Crandall & Moriarty, 2011, p.74). The second—‘symbolic threat’—threatens the vitality of society via endangering “ideology, and an understanding of how the social, political, and/or spiritual worlds work” (Crandall & Moriarty, 2011, p.74). This classification has identified two pathways to predict mental illness stigma.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the mechanisms by which threat influences stigma outcomes. ‘Culture-specific’ threat is shown to overlap partially with ‘tangible’ and ‘symbolic’ threats while also representing a distinct form of threat that leads to stigmatization.

Tangible threat

Representations of physical dangerousness comprise one ‘tangible’ threat via perceived peril to one’s physical safety. Corrigan et al. (2001, 2005) demonstrated in two studies that perceived dangerousness directly engenders affective reactions of fear, which then predisposes behaviors such as social distancing and rejection.

Symbolic threat

In parallel, attributions of responsibility (Weiner, 1985)—by implying an individual’s volitional role in causing a stigmatizing condition—constitute a second threat. A ‘symbolic’ threat exists in that a lack of restraint by the individual in acquiring mental illness threatens the ethical order of society (Stangor & Crandall, 2000). A ‘symbolic threat to societal order’ proposes that perceiving that one had control over the origin of mental illness leads to blame, which engenders affective (e.g., anger) and behavioral reactions (e.g., punishment) which result in response to the threat that such individuals pose to societal order. ‘Symbolic’ threat has been formulated in this manner in prior studies (Stangor & Crandall, 2000; Crandall & Moriarty, 2011), and the ‘symbolic threat’ pathway has been empirically supported by two additional studies (Weiner et al., 1988; Corrigan et al., 2005). Finally, three studies showed separate effects of ‘tangible’ and ‘symbolic’ threats, suggesting independent pathways (Crandall & Moriarty, 2011; Feldman & Crandall, 2007; Corrigan et al., 2005).

Mental illness stigma thus draws conceptual roots from apparently ‘universal’ motivations to avert physical and symbolic threat. This framework may also predict differences in mental illness stigma via varying endorsement in levels of ‘tangible’ and ‘symbolic’ threats across different cultures. However, distinct cultural groups are also viewed as varying in their subjective interpretations of what mental illness is seen to threaten most (Yang et al, 2007). We thus extend this ‘universal’ threat framework to evaluate distinct cultural components to help explain cultural differences in mental illness stigma.

Tangible Threat, Symbolic Threat and ‘Threat to Family Lineage’ among Chinese-Americans

Because stigma has been shown to manifest in distinct ways within Chinese culture (Yang & Kleinman, 2008), we identify the example of Chinese groups to illustrate how relevant cultural domains might be incorporated into this stigma threat model. This ‘cultural component’ might include the beliefs, values and practices held by a group, which also includes the individual’s role in negotiating values held by social worlds (Betancourt & Lopez, 1993). Using an anthropological perspective, we identify a new cultural construct—threat to family lineage through genetic contamination via marriage—that may account for heightened stigmatizing attitudes among Chinese groups.

Starting from the original ‘universal’ threat framework, elevations in tangible and symbolic threats may partially account for higher mental illness stigma among Chinese-American groups. First, enduring Confucian traditions emphasize self-cultivation via moderate behavior (Fei, 1992). Because common mental illness stereotypes of dangerousness and unpredictability directly challenge cultural norms of restrained behavior, heightened perceptions of dangerousness may lead to increased fear and stigma outcomes (social distance and restriction). This represents increased tangible threat. Regarding ‘symbolic’ threat, a person’s lack of self-restraint is especially threatening to social order because it indicates a breakdown by the family and society in providing guidance (Fei, 1992). Chinese groups may thereby attribute mental illness to an individual’s lack of cultivation, thus initiating greater perceptions of responsibility, resulting in blame and anger, which predispose stigma outcomes. Accordingly, we first hypothesize that Chinese-Americans will be more likely than European-Americans to distance themselves from people with mental illness and their family members. Second, we hypothesize higher levels of tangible and symbolic threat among Chinese-Americans.

But in solely considering these forms of stigma threat, a core cultural dynamic intrinsic to many Chinese groups is missing. As identified by seminal ethnographies (Yang & Kleinman, 2008), one key social motivation is to extend one’s family lineage and to make it prosper (Kleinman & Kleinman, 1993). To continue one’s lineage into perpetuity—thus assuring placement into “an eternal chain of filial children” (Stafford, 2006, p. 86)—permeates everyday interactions. Accordingly, the activities that determine one’s status as a ‘full adult’ member revolve around an individual’s engagements to continue one’s lineage to extend into perpetuity (Stafford, 2006). For ensuing generations, there are obligations to produce offspring and to cultivate the lineage’s reputation (Yan, 2003). Corroborating quantitative findings stem from Taiwanese subjects also scoring highest on temporal farsightedness— that one’s actions both result from ancestral deeds and affect future generations—among all ethnic groups studied (Chia et al., 1994). We thus identify as a core Chinese cultural construct the ways that stigma can taint the future family lineage. We conceptualize this culture-specific component as partially overlapping the other two threat constructs, but also contributing distinct variance in predicting stigma (Figure 1).

Because lineage is perpetuated through marriage, we propose that mental illness stigma in Chinese-Americans will pose a threat via suspected psychiatric history in the family ancestry and the genetic make-up of marriage candidates (Wonpat-Borja et al., 2010). We thereby used threat of genetic contamination through marriage as a proxy measure to infer the existence of a culture-based lineage threat among Chinese-Americans. In contrast among many European-Americans, individualism—or the emphasis on freedom to exercise choice dating back to the 1800’s (de Tocqueville, 1832)—promotes an autonomous individual worldview. Many such individuals are thus motivated to view the self as composed of unique, internal attributes (Markus & Kitayama, 1991) unlinked to past or future generations (Chia et al., 1994). We thus propose that averting threat to the future lineage, as operationalized by the threat of genetic contamination, may be heightened among Chinese-Americans, but not European-Americans. Thus, our third hypothesis states that this culture-specific construct will contribute unique variance in predicting stigmatization among these two groups.

Study 1

Study 1 utilizes a preexisting epidemiological sample of Chinese-Americans and European-Americans obtained from a national telephone vignette survey. Each respondent was presented one vignette describing a person with symptoms of mental illness (depression or schizophrenia; adapted from the 1999 General Social Survey, Phelan, 2005). Including depression and schizophrenia suited Study #1 by enabling examination of stigma towards mental illness generally.

We propose three sets of hypotheses comparing Chinese-Americans vs. European-Americans:

Hypothesis #1 predicts that Chinese-Americans will show elevated stigma outcomes (hereafter, we refer to ‘stigma outcomes’ as ‘stigma’) via: a) social restriction towards marriage and childbearing and b) intimate social distance towards people with mental illness and their family members (i.e., sibling or child).

Hypothesis #2 predicts that ‘tangible’ threat, ‘symbolic’ threat, and threat of genetic contamination--operationalized by introducing a) mental illness and b) pathogenic genes into one’s family lineage via marriage--will be higher among Chinese-Americans.

Hypothesis #3 tests how these three threat sources may mediate any cultural variation in stigma (i.e. social restriction or social distance) between groups (Barron & Kenney, 1986). Mediation holds if, after accounting for the effect of one or more threat items on stigma, ethnicity exerts an attenuated or nonsignificant effect on stigma. We first examine the unique contribution of threat of genetic contamination to test its independent effect. To then evaluate the overall threat model’s utility, the ‘tangible’ and ‘symbolic threat’ constructs are entered first to predict social restriction and social distance, followed by threat of genetic contamination. We hypothesize that threat of genetic contamination will significantly predict cultural variation in stigma independently and after accounting for cultural effects via the other threat constructs.

Method

Sample and Procedures

The study sample consists of a subsample of Chinese-Americans (n=56) and European-Americans (n=589) who participated in a vignette experiment of public attitudes and stigma conducted from 2002–2003 (see Phelan, 2005). After receiving one vignette, respondents responded to questions regarding the vignette character.

Respondents were persons age ≥18, living in households with telephones, in the continental U.S. The sampling frame was derived from a list-assisted, random-digit-dialed (RDD) telephone frame. Telephone interviews, ranging from 20–25 minutes long, occurred between June 2002 and March 2003. While these procedures yielded the entire European-American sample, a non-probability sample of Chinese-Americans (n=43) was obtained via ethnic surnames in a national telephone directory to supplement the original RDD sample (n=13). Interviews were in English (n=38) or Chinese (n=18) depending on the subject’s preference. Response rates were 24% for the Chinese-American oversample, and 62% for the original RDD group. Study protocols were approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics for the Chinese-American and European-American samples include gender, age, education, percent foreign-born, household income, political view and religion. Table 1 lists these characteristics (with the exception of political view); selected variables are compared with nationally representative data (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Both samples appear more educated and more female than the national group, which is typical of national surveys (Phelan, 2005).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Comparison with 2000 Census Data

| Sociodemographic Variable | Chinese-American | European-American | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Census | Sample | Census | |

| Average age (years) | 41.8(16.3) | 42.7 | 49.8(16.6) | 46.6 |

| Female (%) | 60.0 | 52.4 | 64.3 | 51.7 |

| College education or more among those >25yrs (%)a | 66.7 | 51.6 | 58.7 | 40.7 |

| Median family income (dollars)b | 56,880 | 60,058 | 54,468 | 53,356 |

| Foreign-born (%)c | 75.4 | 70.8 | --- | --- |

| Religious preference (%) | ||||

| Christian | 19.6 | --- | 70.9 | --- |

| Buddhist | 26.8 | --- | .7 | --- |

| Jewish | 0 | --- | 2.2 | --- |

| No religious preference | 50 | --- | 16.1 | --- |

| Other religion/don’t know | 3.6 | --- | 10.1 | --- |

Note: Standard deviations are noted in parentheses.

Census reports educational attainment for individuals 25 years or older.

Median family income is reported in 2001 dollars for the sample and 1999 dollars for the census.

Census reports percentage foreign-born for all individuals, whereas the sample includes only individuals 18 years or older.

The Chinese-American sample was younger [t(643)=2.80, p<.01], more highly educated [χ2(6)=22.54, p<.01], and more liberal (1=liberal; 5=conservative) than the European-American sample [2.92 vs. 3.30, t(643)=2.65, p<.01]. Likewise, Chinese-Americans and European-Americans differed by endorsed religion (χ2(5)=173.47, p<.001). We control for key sociodemographic variables below.

Measures

Vignettes

This study used two sets of 2 vignettes each: in each set, one vignette described psychiatric symptoms related to schizophrenia (SCZ) and the other vignette described major depressive disorder (MDD). Vignette sets were similar in description of psychiatric symptoms. Sets were created to ensure that hypothesized effects were not due to a specific symptom or vignette description.

Chinese-translated vignettes underwent professional translation and back-translation. The vignette subject’s ethnicity was matched to respondents’ ethnicity. For simplicity, we present the SCZ vignette from vignette set #1 (for all other vignette versions, see Appendix).

Vignette #1-Schizophrenia

Imagine a person named Jung. He is a single, 25-year old Chinese-American man. Usually, Jung gets along well with his family and coworkers. He enjoys reading and going out with friends. About a year ago, Jung started thinking that people around him were spying on him and trying to hurt him. He became convinced that people could hear what he was thinking. He also heard voices when no one else was around. Sometimes he even thought people on TV were sending messages especially to him. After living this way for about six months, Jung was admitted to a psychiatric hospital and was told that he had an illness called “schizophrenia.” He was treated in the hospital for two weeks and was then released. He has been out of the hospital for six months now and is doing OK.

Participants were randomly-assigned to vignette set and illness type. Data from both vignette sets #1 (n=472) and #2 (n=173) were combined to maximize sample size. Subjects were randomly-assigned a vignette character with the symptoms and diagnosis of SCZ (n’s=28 and 302; Chinese-Americans and European-Americans, respectively) or MDD (n’s=28 and 287; total psychiatric condition vignettes, n’s=56 and 589). Because of possible effects that vignette set (#1 vs. #2) and psychiatric illness type (SCZ vs. MDD) might have on outcomes, all regression analyses controlled for these variables’ effects. Once vignette set and illness type were controlled for, no other vignette manipulations (see Phelan, 2005) had an effect on any dependent variable, and are not discussed further.

Dependent Variables

For item wording and response sets of all measures, see Appendix. All items used a 4-point response set with higher scores indicating greater stigma. All items were scored as single items, with the exception of social distance, which was scored as the average of summed scale items.

Stigma Constructs

Social Restriction

Social restriction was measured by two single items assessing agreement whether Jung should not be allowed to marry (not marry) or have children (no children).

Social distance

Social distance was measured by a three-item scale assessing unwillingness to have Jung date/marry/have a baby with a child of the respondent. These three different versions were randomly assigned as a 3-item scale to respondents, with respondents receiving one scale only (see Phelan, 2005). The intimate social distance scale (α=.93; =260)n referred to Jung (e.g., “How would you feel about having Jung marry one of your children?”). The intimate social distance from the sibling scale (α=.92; =212) referred to Jung’s sibling (e.g., n “How would you feel about having Jung’s sibling marry one of your children?”). The intimate social distance from the child scale (α=.90; =173) referred to Jung’s child (e.g., “How would n you feel about having Jung’s child marry one of your children?”).

Threat Constructs

All respondents received two single-item measures, each with a 4-point response set (see Appendix), to assess each of the three threat constructs.

‘Tangible’ Threat

Tangible threat was measured by assessing agreement that Jung would be violent (violent) or elicit fear (fear).

‘Symbolic’ Threat

Symbolic threat was measured by assessing agreement that Jung was to blame for his condition (blame) or would elicit anger (anger).

Threat of Genetic Contamination

Threat of contaminating the genetic purity of the lineage was measured by assessing agreement that knowing a marriage partner’s familial history of mental illness is important (history MI) or that genetic screening should be required before marriage (screening).

Power Analyses

With a sample-size of 56 Chinese-Americans and 589 European-Americans, with alpha set at .05, we have 80% power to detect an estimated effect size difference (Cohen’s D) of .22 in our dependent variables, which is considered a small effect size (Cohen, 1988). Missing data for specific questions was relatively rare (range 0 to 5.5%) and was addressed by conditional mean imputation using regression analysis (Allison, 2002) for continuous sociodemographic variables only. Missing values for any of the dependent variables resulted in that case being dropped from analyses. Case missingness was found to be independent of ethnicity.

Results

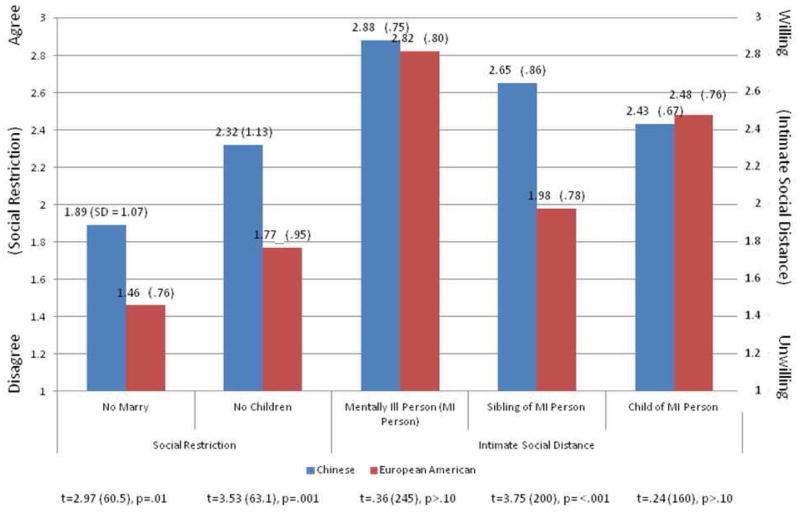

Hypothesis #1: Cultural Differences in Social Restriction and Social Distance

We first used independent-sample t-tests to compare Chinese-Americans with European-Americans on social restriction and intimate social distance (with Jung, Jung’s sibling, and Jung’s child conditions) (see Figure 2). Results for social restriction (scored as single items) reveal that Chinese-Americans were more likely to endorse that people with mental illness should not get married and should not have children. For intimate social distance (scored as the average of three items), Chinese-Americans were more likely to endorse that they were less willing to date, marry, or have a baby with the sibling of a person with mental illness. No differences were found between ethnic groups on their unwillingness to date, marry, or have a baby with a person with mental illness or their child.

Figure 2.

Mean Scores by Ethnicity for Social Restriction and Intimate Social Distance

Controlling for Study Design and Sociodemographic Covariates

We next examined the effects of participants’ ethnicity on the three outcomes described above (i.e., not marry, no children, and intimate social distance from the sibling) via linear regression models controlling for vignette set (#1 vs. #2) and disorder (SCZ vs. MDD). Chinese ethnicity again increased stigma in all outcomes (Table 2, Model 1 of each three variables).

Table 2.

| A. No Marry (N = 628) | B. No Children (N = 617) | C. Intimate Social Distance from Sibling (N = 202) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||

| Ethnicity (Chinese) | .44*** (.11) | .54*** (.11) | .41*** (.11) | .50*** (.11) | .33*** (.10) | .25* (.11) | .56*** (.13) | .66*** (.13) | .45*** (.13) | .60*** (.13) | .44*** (.13) | .30*** (.13) | .66*** (.18) | .72*** (.18) | .53** (.18) | .57** (.18) | .33 (.18) | .23 (.17) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Sociodemographic | Education | --- | −.04* (.19) | −.03 (.19) | −.04* (.19) | −.03 (.18) | −.02 (.18) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .01* (.00) | .00 (.00) | .01 (.00) | .01 (.00) | .00 (.00) |

| Age | --- | .01*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) | --- | .02*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) | .02*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) | --- | .12* (.05) | .14** (.05) | .10 (.05) | .07 (.05) | .08 (.05) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Symbolic Threat | Blame | --- | --- | --- | .16*** (.05) | .14** (.05) | .14** (.05) | --- | --- | --- | .03 (.06) | .00 (.06) | .00 (.06) | --- | --- | --- | .02 (.09) | −.00 (.08) | .02 (.08) |

| Anger | --- | --- | --- | .10 (.08) | −.05 (.07) | −.06 (.07) | --- | --- | --- | .2.3* (.09) | .12 (.09) | .08 (.09) | --- | --- | --- | .38** (.13) | .19 (.13) | .19 (.12) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Tangible Threat | Violent | --- | --- | --- | --- | .11** (.04) | .09* (.04) | --- | --- | --- | --- | .16** (.05) | .12* (.05) | --- | --- | --- | --- | .19** (.07) | .14* (.07) |

| Fear | --- | --- | --- | --- | .31*** (.04) | .30*** (.04) | --- | --- | --- | --- | .23*** (.05) | .22*** (.05) | --- | --- | --- | --- | .28*** (.07) | .27*** (.07) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Threat to Genetic Contamination | Screening | --- | --- | .11*** (.03) | --- | --- | .09** (.03) | --- | --- | .19*** (.04) | --- | --- | .17** (.04) | --- | --- | .11* (.06) | --- | --- | .06 (.05) |

| History MI | --- | --- | .06 (.03) | --- | --- | .04 (.03) | --- | --- | .07 (.04) | --- | --- | .05 (.04) | --- | --- | .23*** (.06) | --- | --- | .22*** (.06) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| R-squared | 4.8% | 12.7% | 15.4% | 14.6% | 24.1% | 25.6% | 11.6% | 19.2% | 24.2% | 2.1% | 25.1% | 28.6% | 6.6% | 11.6% | 22.3% | 15.2% | 27.2% | 34.8% | |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .06

Notes: Model 1= Ethnicity entered controlling for vignette set (#1 vs. #2) and vignette disorder (SCZ vs. MDD); Model 2= Adding significant sociodemographic covariates only to Model 1; Model 3= Adding threat of genetic contamination variables to Model 2; Model 4= Adding symbolic threat variables to Model 2; Model 5= Adding tangible threat variables to Model 4; Model 6= Adding threat of genetic contamination variables to Model 5. Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors are shown only for ethnicity, significant sociodemographic covariates, and potential mediators. Standard errors are in parentheses. Sample size for social distance is substantially smaller because respondents were randomly assigned to answer social distance questions about the vignette subjects or the sibling.

Key sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education, family income, political conservatism, and religion) were simultaneously entered into the Model 1 equations to control for any potential confounds. Only significant covariates were included in Model 2 (Table 2); controlling for these covariates (and in particular, age) boosted ethnicity’s effect on stigma across all outcomes.

Hypothesis #2: Effects of Culture on Threat Constructs

We next examined whether the three threat constructs were heightened among Chinese-Americans vs. European-Americans.

‘Tangible’ Threat

Chinese-Americans (n=56, M=2.67, SD=.91) perceived people with mental illness as more violent than European-Americans (n=589, M=2.30, SD=.76; t(62.5) =2.90, p< .01). Further, Chinese-Americans (n=56, M=1.95, SD=1.01) perceived that people with mental illness elicited more fear than European-Americans (n=589, M=1.47, SD=.72; t(60.5) =3.47, p<.001).

‘Symbolic’ Threat

Chinese-Americans (n=56, M=1.39, SD=.73) were no more likely to blame people with mental illness for their condition than European-Americans (n=589, M=1.29, SD=.60; t(62.4)=.99, p>.10). However, Chinese-Americans (n=56, M=1.32, SD=.71) endorsed more anger towards people with mental illness than European-Americans (n=589, M=1.11, SD=.36; t(57.7)=2.14, p<.05).

Threat of Genetic Contamination

Chinese-Americans (n=56, M=2.70, SD=1.14) were more likely to endorse that genetic screening should be required before marriage than European-Americans (n=589, M=1.89, SD=1.01; t(643)=5.60, p<.001). Further, Chinese-Americans (n=56, M=3.38, SD=.95) were more likely to stress the importance of knowing a potential marriage partner’s family history of mental illness than were European-Americans (n=589, M=2.95, SD=.99; t(643)=3.09, p<.01).

Intercorrelations between Threat Constructs

Our threat model (Figure 1) describes the three threat constructs as relatively independent. Items were in fact significantly correlated within threat domains, with lower correlation between threat domains. As expected, Violent was significantly correlated with Fear, r(645)=.37, p<.001, with all other correlations between threat constructs and Violent ≤.15. Similarly, Blame was significantly correlated with Anger, r(645)=.16, p<.001, with all other correlations between threat constructs and Blame ≤.08 or less. Finally, History MI was significantly correlated with Screening, r(645)=.39, p<.001, with all other correlations between threat constructs and History MI ≤.12.

Hypothesis #3: Explanatory Effects of Threat Constructs on Cultural Variation in Stigma

Hypothesis #3 examines the explanatory effects of these three sources of threat. We first tested whether threat of genetic contamination alone mediated the effect of culture on each stigma outcome (i.e., social restriction and intimate social distance; Barron & Kenny, 1986). Next, to test whether the threat of genetic contamination uniquely increased prediction of stigma, we tested whether these items predicted cultural variation even after accounting for tangible and symbolic threat.

Threat of Genetic Contamination: Independent Effects

The two threat of genetic contamination items were first entered simultaneously into a regression model after participant ethnicity and sociodemographic covariates (Model 3, Table 2). When entered as a block, these threat items significantly explained variance for no marry (2.8%), no children (5.0%), and intimate social distance from the sibling (10.7%; each p<.001). If these threat items at least partially explain ethnicity’s effect on stigma, the coefficient for ethnicity reported in Model 2 (Table 2) should decrease after these items are entered (Model 3, Table 2). Accounting for threat of genetic contamination, the regression coefficients for ethnicity drop substantially by 23.9% (.536 to .408) for no marry, 31.1% (.659 to .454) for no children, and 26.5% (.720 to .529) for intimate social distance from the sibling.

We next examine the distinct explanatory effects of the threat of genetic contamination on ethnicity after ‘symbolic’ and ‘tangible’ threat items are added. These threat constructs are added sequentially into regression models after entering ethnicity and other significant covariates (see Model 2, Table 2).

‘Symbolic’ Threat

Model 4 (Table 2) depicts the mediating effects of the two ‘symbolic’ threat items. When entered as a block, these threat items predicted all stigma outcomes (each p<.05). When comparing the coefficients for ethnicity before (Model 2, Table 2) and after (Model 4, Table 2) ‘symbolic’ threat items were added, the regression coefficients for ethnicity drop moderately by 7.1% (.536 to .498) for no marry, 8.5% (.659 to .603) for no children, and 20.3% (.720 to .574) for intimate social distance from the sibling.

‘Tangible’ Threat

Model 5 (Table 2) depicts the explanatory effects of the two ‘tangible’ threat items on ethnicity with the ‘symbolic threat’ variables already entered. When entered as a block, the two ‘tangible’ threat items aided prediction of all stigma outcomes (each p<.001). When adding violent and fear, the regression coefficients for ethnicity again drop substantially-- 33.9% (.498 to .329) for no marry, 26.4% (.603 to .444) for no children, and 42.7% (.574 to .329) for intimate social distance from the sibling. The ‘tangible’ threat items also appeared to mediate the effects of the ‘symbolic’ threat items on two stigma outcomes, with only blame still significantly predicting no marry.

Threat of Genetic Contamination

We enter the threat of genetic contamination items last to test if they might explain ethnicity’s effect on stigma even after accounting for the ‘symbolic’ and ‘tangible’ threat items. When entered as a block (Model 6, Table 2), the two genetic contamination threat items explained additional variance for the stigma outcomes of no marry (1.5%), no children (3.5%), and intimate social distance from the sibling (7.6%; each at p<.01). The regression coefficients for ethnicity also decreased by a further 25.2% (.329 to .246) for no marry, 32.4% (.444 to .300) for no children, and 31.3% (.329 to .226) for intimate social distance from the sibling. Thus, the threat of genetic contamination items powerfully accounted for ethnicity’s effects on stigma even after other threat constructs were entered.

We lastly evaluate our threat model by entering all three threat constructs and comparing the ethnicity coefficients in Model 2 (without any threat items) to Model 6 (ethnicity’s remaining effect on stigma after all threat items are entered). After entering all threat constructs, the coefficients for ethnicity decreased by 54.1% (.536 to .246) for no marry, 54.5% (.659 to .300) for no children, and 68.6% (.720 to .226) for intimate social distance from the sibling. Further, while the final ethnicity coefficient for no children remained strongly significant (at p<.001) even after entering all threat items (Model 6, Table 2, Section B), adding the genetic contamination threat items as a final step to Model 5 decreased the significance of ethnicity in predicting no marry from strongly significant (p<.001) to just significant (p<.05; Model 6, Table 2, Section A), and for intimate social distance from the sibling from trend significance (p=.06) to non-significance (p>.10; Model 6, Table 2, Section C). Thus, the effect of ethnicity on stigma is substantially mediated by the three threat constructs for no marry and no children, and fully mediated for intimate social distance from the sibling.

Discussion

Hypothesis #1 showed cultural differences in three of five stigma outcomes that allowed examination of the mediating effects of the threat constructs. Per prior studies (Shookohi-Yekta & Retish, 1991; Furnham & Wong, 2007), Chinese-Americans evidenced more socially restrictive attitudes. Further, there was partial support for hypothesized differences in intimate social distance as Chinese–Americans endorsed more intimate social distance towards the sibling of a person with mental illness. However, ethnic differences in intimate social distance did not extend to the person with mental illness, or that person’s child. On the one hand, elevated intimate social distance towards a person with mental illness among European-Americans is not surprising given prior findings in another nationally-representative sample (Link et al., 1999). However, that European-Americans endorsed equivalent intimate social distance towards the child of a person with mental illness than did Chinese-Americans was unexpected. One possible explanation is that European-Americans attributed similar levels of genetic transmission of mental illness to children than do Chinese-Americans, but that these beliefs do not extend to siblings. This unanticipated finding requires further investigation.

Hypothesis #2 showed cultural influences on five of six threat items. Like other studies (Furnham & Wong, 2007), ‘tangible’ threat among Chinese-Americans was endorsed more highly. Further, that threat of genetic contamination was greater among Chinese-Americans corroborates greater concerns of genetic transmission of mental illness in this group (Wonpat-Borja et al., 2010). Regarding ‘symbolic’ threat, only anger was significantly higher in Chinese-Americans. The nonsignificant findings concerning controllability may be due to an emphasis on social causation among Chinese, which might lessen perception of individual responsibility for mental illness (Yang et al., 2004).

Our study is the first to identify the specific threat processes that underlie greater mental illness stigma among Chinese groups. Heightened perceptions of ‘symbolic’ and ‘tangible’ threat, along with threat of genetic contamination, substantially mediated the effect that ethnicity had upon stigma for the two social restriction outcomes and fully explained differences in ‘intimate social distance towards the sibling’. Key to our conceptualization, Hypothesis #3 showed that threat of genetic contamination among Chinese-Americans significantly predicted unique cultural variance in all three stigma outcomes independently, and also after cultural influences via other threats were accounted for.

Despite its strengths, Study 1 is not without limitations. One limitation is the sample. European-Americans were older and Christian. It is possible that European-Americans had adult children which would lessen their sensitivity to offspring issues and Christianity may have increased their tolerance to the mentally ill (Gray, 2001). This limitation is balanced by socio-demographic variables being controlled for in all analyses. Second, our null findings (i.e., for intimate social distance) may be due in part to the unequal size in groups, as power to detect significant differences would have been greater had groups been more balanced in size. However, we remain fairly confident in the null results as power was still adequate to detect even a small effect size. Third, the low response rate and nonprobability nature of the Chinese-American supplementary sample precluded application of weights, thus limiting generalizability of our findings to this group nationally. However, this group, while not nationally-representative, was still community-ascertained and thus was superior to a convenience sample. Lastly, the study’s non-experimental design precludes definitive causal inference between concerns about family lineage and stigma, as greater stigma may result in elevated lineage-based concerns. These limitations motivated using a different method and outcome measure to explore whether genetic contamination via marriage constitutes a culturally-specific form of threat among Chinese groups.

Study 2

Study 2 was a laboratory experiment. We examined whether Chinese groups are attuned to and remember information about a mental illness when it could potentially taint one’s family lineage through genetic contamination. We argue that genetic defects may pollute family lineage, thus heightening threat among Chinese groups. People tend to show greater memory for information they are threatened by (Yiend & Mathews, 2001). Accordingly, in Study 2 memory was used to indirectly assess threat. One advantage of memory measures is that they are not susceptible to biases found in self-report measures.

Chinese and European-American groups were provided a vignette character (Jung) who, soon to marry his fiancé, becomes increasingly concerned about his mental illness symptoms. In the vignette, physical dangerousness (i.e., tangible threat), and danger to society through the person’s behavior (i.e., symbolic threat) remained constant across conditions. A doctor explained the cause of the protagonist’s illness as genetic or not genetic. Thus, a diagnosis that could raise concerns about family lineage varied between conditions. The experiment was a 2 (culture: Chinese, European-American) × illness explanation (genetic, non-genetic) between-subjects design.

The vignette included two types of statements that remained identical across illness explanation condition. Some statements described the vignette character’s illness symptoms (e.g., “thinks people on TV are sending messages to him”). We also integrated new statements relevant to genetic contamination through marriage (e.g., “feared his illness might be passed onto future generations”). If Chinese groups are especially sensitive to concerns about preserving family lineage, then Chinese groups in the genetic-cause condition should be more attuned to information relevant to genetic contamination than in the non-genetic cause condition. No differences between conditions should be found among European-American participants.

To test this, we assessed memory for vignette content using both a free-recall task (Cacioppo & Petti, 1981) and a recognition-comprehension task (true-false) (Woike et al., 1999). We predicted that genetic explanations but not non-genetic explanations would increase memory for statements relevant to genetic contamination for Chinese groups. No differences should be found among European-American participants. Further, we predicted that for both Chinese and European-Americans, genetic explanations would have no effect on memory for statements related to illness symptoms.

Sample and procedures

The target population was students recruited from universities in New York City from June to August 2010 who self-identified as Chinese (immigrants or Chinese-Americans with one parent born in China) or European-American (≥1 parent born in U.S.). Eligible subjects were 48 Chinese and 37 European-Americans. They were compensated $12.00. Participants were randomly-assigned to condition.

After consent, participants were told they would read a story then respond to questions. First, participants read the vignette about a character suffering from schizophrenia. Next, participants completed a distracter task and were then given an unexpected recall task. Following free recall, they completed the recognition task, and finally all additional study measures. Participants were probed for suspicion, using funnel debriefing; none guessed the hypotheses. Study protocols were approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University.

Demographic characteristics

Table 3 provides the Chinese-American and European-American samples’ characteristics, including gender, age, education, place of birth, household income, political view and religion.

Table 3.

Sample Characteristics for Study 2

| Sociodemographic Variable | Chinese American | European American |

|---|---|---|

| Sample | Sample | |

| Average Age (in years) | 23.1(4.2) | 23.3(2.9) |

| Female (%) | 72.9 | 54.1 |

| Highest level of educationa | 4.9 | 4.0 |

| Median family income (in dollars) | $20,000–$30,000 | $50,00–$60,000 |

| Foreign-Born (%) | 81.3 | --- |

| Political Views (1=very liberal: 7=very conservative) | 3.3 | 1.8 |

| Religious Preference (%) | ||

| Christian | 6.3 | 19.9 |

| Buddhist | 6.3 | 0 |

| Jewish | 0 | 11.1 |

| No religious preference | 83.3 | 54.1 |

| Other religion/don’t know | 4.1 | 14.2 |

Note: Standard deviations are noted in (parentheses).

Highest level of education was scaled such that 4 = completing BA and 5 = completing MA, MBA, MD, law school degree

When comparing the Chinese-American and European-American groups, the Chinese-American sample was lower in income [t(75)=2.83, p=.006], more highly educated [t(75)=2.86, p=.005], and more conservative [t(75)=5.26, p<=.000] than the European-American sample. Likewise, Chinese-Americans and European-Americans differed by endorsed religion (χ2(7)=19.16, p=.008). Controlling for each demographic variable above in recall and recognition analyses did not significantly change reported results. Moreover, none of the variables emerged as a significant covariate in recall and recognition analyses and thus are not discussed further.

Materials

Vignettes

Because universities educate students about major depression because of its high prevalence (Kitzrow, 2003), Study 2 included only vignettes describing schizophrenia. As per Study 1, participants’ race/ethnicity was matched to that of the vignette character. Each vignette (genetic-cause vs. non-genetic cause) contained 12 statements; six statements about the character’s symptoms and thoughts (‘symptoms and experiences content’) and six statements related to genetic contamination (‘contamination content’). These statements did not vary by condition.

Experimental manipulation

At the end of the vignette, a geneticist described a “genetic” vs. “non-genetic” etiology of schizophrenia. The ‘genetic-cause’ condition read, “…his problem had a very strong genetic or hereditary component.” The ‘non-genetic’ cause condition read, “his problem was not due to a hereditary or genetic factor, especially since his family has no history of mental illness.”

Measures

Recall

Participants wrote down as many recalled thoughts in 10 empty text boxes (see Cacioppo & Petty, 1981). While our primary interest was recall of statements of genetic contamination and illness symptoms, we analyzed content of all recalled statements without forcing responses into hypothesized categories.

Coding scheme

Each sentence was coded as one response unit which was stripped of any ethnically-identifiable information. Two coders categorized based on emergent themes (κ=.86) and were unaware of hypotheses and condition. The final coding scheme comprised 9 categories (see Table 4 for examples): 1) Concerns about transmitting illness to future children; 2) Character and fiancé’s relationship; 3) Fiancé’s interest in marrying a healthy man; 4) Character’s concealment of illness from fiancé; 5) Character’s thoughts about illness; 6) Scientific background about illness; 7) Character’s demographic information; 8) Other; and, 9) Uncodable. Proportion of recalled statements per statement category was analyzed for the recall task.

Table 4.

Categories for coding responses in the free recall task, interrater reliability, and proportions of each category by ethnicity and explanation type.

| Categories | Examples | Agreement (κ) | European American | Chinese | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Genetic | Neurobiological | Genetic | Neurobiological | |||||

| Concern about passing on the illness to future generations | “The mental illness was heritable” | .74*** | .13 | .13 | .18 | .09 | 4.74 | .032* |

| Concern about telling wife about the illness | “He lied to his wife” | - | .15 | .10 | .07 | .09 | 2.65 | .107 |

| Demographic background of the protagonist | “Jung (John) was 30 years old” | .97*** | .13 | .11 | .07 | .08 | .52 | .472 |

| Experiences with the mental illness | “He thought people on TV were sending him messages” | .81*** | .36 | .37 | .33 | .40 | .63 | .430 |

| Importance of marrying a healthy man | “It was important that she marry a healthy man” | - | .04 | .02 | .03 | .05 | .15 | .233 |

| Other | “She noticed his illness” | .66*** | .02 | .04 | .06 | .03 | 2.10 | .151 |

| Relationship between the protagonist and his fiancé | “Jung (John) has a fiancé” | .92*** | .14 | .15 | .18 | .08 | .01 | .933 |

| Scientific background of the illness | “The illness was neurobiological” | .81*** | .03 | .09 | .05 | .06 | 1.08 | .302 |

| Uncodable | “Imagine a…” (incomplete sentence) | .80*** | .02 | .01 | .03 | .03 | .06 | .808 |

Note: The F and p values are measures of the interaction between ethnicity and explanation for illness. Dashes in the “agreement” column indicate that Kappa was unable to be computed because the table of values computed was asymmetric. Numbers below “European American” and “Chinese” are proportion of recalled statements by statement category.

p < .05

p < .001

Recognition-comprehension

The true-false recognition task included 20 true-false items (Woike et al., 1999) assessing comprehension of statements relevant to genetic contamination of the character’s lineage (10 items) and character’s illness symptoms (10 items). For each of the 10 statements, five were identical to vignette statements and five were false (i.e., had subtle inaccuracies, e.g. “he suffered for six months” vs. “he suffered for six weeks”). Worse recognition suggested less attention to or poorer comprehension of misrecognized content.

Three outcomes were derived (Woike et al., 1999): (1) “Number of correct contamination-relevant statements” (range: 0–10); (2) Contamination-error-percentage, the number of incorrectly recognized contamination-relevant statements divided by the total number of errors (range 0–100%); and, (3) Sensitivity to contamination-relevant information, the number of correctly-recognized contamination statements (0–10) minus the number of false positives (i.e., false items marked as “true”) (range: −5–10). Means for each type of recognition outcome were analyzed for the recognition task.

Chinese acculturation

Participants completed an 8-item measure assessing orientations to Chinese and American cultures (Tsai et al., 2000). Items had a 5-point response set, with higher scores indicating greater Chinese acculturation. Chinese groups scored higher than European-Americans (MChinese=3.80, SD=.64; MEur-Am=1.78, SD=.33; p<.001).

Power Analyses

With a sample-size of 48 Chinese-Americans and 37 European-Americans, with alpha set at .05, we have 80% power to detect an estimated effect size difference (Cohen’s D) of .62 in our dependent variables, which is considered between a medium and a large effect size (Cohen, 1988). Any missing data for variables in Study 2 resulted in cases to be omitted from analyses.

Results

Recall

Participants’ recall of vignette information fell into 9 independent, uncorrelated categories (Cronbach’s alpha=0.06). None of the eight recall categories (i.e., excluding the “uncodable” category) correlated at least .3 with any other category, suggesting non-factorability. We thus examined each recall category separately.

We predicted that among Chinese but not European-American participants, recall for information related to potential genetic contamination would be greater when mental illness was described as being caused by genetic vs. non-genetic factors. To test this, a series of culture x explanation type analysis of variances (ANOVAs) were conducted on each category (Table 4). The only category revealing a significant interaction was “concerns about transmitting illness to future children.” This ANOVA revealed a main effect of genetic-cause vs. non-genetic cause condition, F(1,80)=4.30, p=.041 which was qualified by a significant culture × explanation type interaction, F(1,80)=4.74, p=.032. No other effects were significant. Among Chinese, when mental illness was described as being caused by genetic factors, recall of statements about illness transmission was greater than when a non-genetic cause was described, F(1,80)=10.55, p=.002. European-American participants’ recall was unaffected by explanation type, Fs<1. Hence, when mental illness etiology included a genetic component, Chinese but not European-Americans recalled information relevant to potential genetic contamination, presumably activated by this culture-specific threat.

Recognition-comprehension

The recognition task assessed how precisely participants remember information in the vignette. Results were consistent with the recall task. Total number of correct contamination-relevant responses was analyzed with the same culture × explanation type ANOVA. Results revealed a significant interaction, F(1, 80)=6.08, p=.016 (Table 5). No other effects were significant. Chinese participants were more likely to correctly identify contamination-relevant statements as true when mental illness was ascribed to genetic factors vs. non-genetic causes, F(1, 80)=4.02, p=.048. For European-Americans, there was no significant difference in recognition between conditions, Fs<1. Examining pattern of errors (i.e., dividing the total number of contamination-relevant errors by the total number of errors) revealed the same pattern of effects (p<.05). Further, utilizing the sensitivity measure (d′), which is useful for distinguishing between subjects who chronically respond “true” from those who are uniquely sensitive to contamination-relevant content (Woike et al., 1999), yielded congruent results (p<.05).

Table 5.

Recognition task: Means, standard deviations, and interactions of ethnicity and explanation type on number of correct responses, percentage-of-contamination-relevant-errors (reversed), and sensitivity to contamination content

| European American | Chinese | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic | Neurobiological | Genetic | Neurobiological | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Means | Standard deviations | Means | Standard deviations | Means | Standard deviations | Means | Standard deviations | F | p | |

| Number of correct contamination-relevant responses | 7.47 | 1.12 | 8.10 | 1.41 | 7.69 | 1.19 | 6.95 | 1.16 | 6.36 | .014* |

| Percentage of contamination-relevant errors (reversed) | −.50 | .22 | −.39 | .23 | −.42 | .14 | −.57 | .19 | 8.93 | .004** |

| Sensitivity to contamination content | 5.65 | 2.43 | 6.65 | 2.62 | 5.92 | 1.94 | 4.48 | 2.06 | 6.20 | .015* |

Note: The F and p values are measures of the interactions between ethnicity and explanation type: df = 80 for all variables. Values under “European American” and “Chinese” are the means and standard deviations of the number of correct responses, percentage of contamination-relevant errors (reversed), and sensitivity to contamination content, by explanation type (genetic vs. non-genetic)

p < .05

p < .01

We next examined performance on the recognition task for content about the character’s symptoms/feelings about his illness. No differences among Chinese or European-American participants in the total number of correct responses for statements relevant to character’s illness experiences were expected. Using a 2 × 2 ANOVA, no main or interaction effects were significant, all Fs<1.3.

Chinese acculturation

To test acculturation as a potential moderator we switched to regression as recommended by West and Aiken (1991). We conducted a linear regression in which recall for lineage statements was regressed on ethnicity, explanation for illness type, acculturation, and the interactions of these variables. Acculturation was mean-centered. Analyses revealed no significant effect of acculturation for recall, p>.3. Analyses were repeated for each recognition variable and no significant effects emerged, all ps>.3.

Discussion

Study 2 used an experimental memory paradigm utilizing vignettes to directly test a Chinese culture-specific perception of threat. The recall and recognition tasks revealed evidence consistent with Study 1. In the genetic condition, Chinese were both more likely to spontaneously recall and to recognize statements about genetic contamination through marriage when compared with European-Americans. However, they were not more accurate at detecting statements related with symptom experiences. Threats are strong competitors for attention, and consequently, memory for threats would be stronger (Bishop et al., 2004). Study 2 thus is consistent with the hypothesis that Chinese groups experience threats related to family lineage particularly when lineage-relevant information is made salient in their immediate social context. That our experiment utilized random assignment and we found no effects of sample characteristics on dependent variables increases our confidence that effects are not explained by sample differences.

Study 2 has several limitations. Namely, acculturation did not moderate our results, despite Chinese participants scoring higher on the Chinese acculturation scale than European-American participants. On one hand, one might expect memory effects to be moderated by acculturation. Alternatively, acculturation measures which tend to focus on affect (“I am proud to be Chinese”) may not capture cultural behaviors that would moderate concerns about potential danger to lineage. It is also possible that threat to genetic contamination is distinct from acculturation constructs which have typically been associated with cultural psychological research (Kleinman, 1989). As another possibility, due to the relatively small sample size in Study 2, we cannot be as confident about our null findings as power was only adequate to detect a medium-to-large effect size (i.e., even a medium effect size would be interpreted as a null finding). Another potential limitation is that it would have been desirable to directly assess threat (instead of using memory as a proxy) and the degree to which respondents attributed mental illness to genetic causes as a result of the vignette condition. A final limitation is that we sampled a convenience sample of college students; results therefore might be generalizable only to this group. Future research might better address these methodological and study limitations.

General Discussion

Supporting past work comparing mental illness stigma among Chinese vs. Western groups (Shokoohi-Yekta & Retish, 1991; Furnham & Wong, 2007), Study 1 indicated increased levels of stigma (i.e., social restriction and intimate social distance) and perception of threat (i.e., symbolic, tangible, and threat of genetic contamination) among Chinese groups. Our results extend prior studies showing independent pathways for symbolic and tangible threats in predicting stigma by identifying and examining the effects of a ‘culture-specific’ source of threat (Crandall & Moriarty, 2011; Corrigan et al., 2005). Based upon seminal anthropological work, we apriori identified perpetuation of the family lineage via marriage as a fundamental everyday interaction among many Chinese groups, which subsequently explained unique cultural variation in stigma.

We proposed that threat of genetic contamination, in being central to everyday interactions within Chinese groups but not European-American groups, would be distinct from symbolic and tangible threats. The genetic contamination threat items did appear to be largely distinct from other threat items, as the correlation between genetic contamination threat items was highest, with lower correlations in relation to either tangible or symbolic threat. Further, this culture-specific threat appeared to capture unique elements of culture, as it explained ethnicity’s effect on stigma in Study 1 even after accounting for other threats. This evidence indicates that concerns about genetic contamination constitute an independent, and empirically useful, construct in predicting stigma in Chinese groups.

Further Examination and Consideration of ‘Threat to Lineage’ among Chinese Groups

While we based our identification of ‘threat to lineage’ upon extensive prior anthropological fieldwork (Yang & Kleinman, 2008), we did not directly test for lineage concerns as ‘what matters most’ among Chinese groups. This did not allow direct testing of whether lineage concerns differed among Chinese vs. European-Americans. Also, most of the Chinese American respondents from Studies 1 and 2 were college-educated in the U.S.; thus, we cannot be certain whether Chinese in other parts of the world might also evidence this lineage concern. Nor did we explicitly test whether a threat to lineage among Chinese groups caused greater mental illness stigma (although this is examined in a companion qualitative paper—see Yang et al., 2013). We instead infer the existence of this culture-based lineage threat among Chinese-Americans by using threat of genetic contamination as a proxy measure. Notably, the threat of genetic contamination measure explained ethnic differences in stigma in Studies 1 and 2 in a way consistent with that of a lineage-based threat. However, future studies might even more explicitly identify and test the effects of threat to lineage among these ethnic groups. Further, whether perceived threat to lineage might also exist among other ethnic groups in addition to the Chinese respondents typified by our sample might also be investigated.

Given the convergence of evidence to suggest the existence of a threat to lineage among Chinese groups, we further propose that this culture-specific threat may impact stigma in other conditions among Chinese, including HIV/AIDS (Mak et al., 2007). We propose that stigma of HIV/AIDS might constitute a threat to lineage among Chinese groups, but via mechanisms other than genetic contamination. Here ethical judgments of behaviors perceived as linked with HIV, such as drug use, commercial sex, or homosexuality directly attacks the self-cultivation necessary for full-fledged ‘personhood’ in China (Hesketh et al., 2005). This contamination of character is potent enough to imperil the family’s ability to negotiate crucial social opportunities such as marriage, thus threatening the lineage. Uninfected relatives thereby move to preserve the lineage from such danger (Yang & Kleinman, 2008). One vivid illustration among indigenous Chinese groups occurs whereby the bodies of drug-abusing and commonly HIV-positive relatives were placed in separate graveyards so that their evil spirits would not contaminate ancestors and offspring (Deng et al., 2007). We thus propose that this core obligation to lineage is susceptible to threat by a myriad of stigmatizing conditions.

Linkages to ‘What Matters Most’ Locally and Stigma

Culture-specific threats vary by cultural context and, we propose, are determined by the fundamental everyday interactions of a social world. The cultural-specific threat of genetic contamination among Chinese groups reflects a prior conceptualization that stigma coalesces around those life engagements that ‘matter most’ within a local cultural context (Yang et al., 2007). That is, while stigma affects many life domains, it is felt most acutely upon the everyday interactions that define ‘personhood’ within cultural groups. This approach, which draws from research on social dimensions of illness (Kleinman, 1989) emphasizes how stigma is embedded in the “moral mode” of experience.

‘Moral’ in this sense, instead of demarcating right from wrong, refers to features of everyday life characterized by the regular, daily engagements that define “what matters most” for individuals within a local world. To effectively engage in these everyday interactions is to be certified as a full person. While we have identified the preservation of lineage as what defines ‘personhood’ within many Chinese groups, examples of what might be ‘most at stake’ in other social worlds consist of the pursuit of distinct core lived values including status, money, life chances, health, good fortune, a job, or relationships (Kleinman, 1989). Further, while preservation of lineage appears to form a central aspect of ‘what matters most’ among Chinese groups, other core cultural concepts, such as ‘face’ (Yang & Kleinman, 2008) might be closely linked, and incorporated, with lineage concerns. Both the stigmatizers and the stigmatized are engaged in a similar process of holding onto and preserving what matters, and warding off threat to what comprises ‘personhood. Future work might examine the applicability of this conceptual framework in elaborating the culture-specific constructs to predict stigma in this and other cultural groups.

Future Directions

Our findings have implications for anti-stigma interventions by targeting culture-specific perceptions of threat towards mental illness in Chinese groups (Yang et al., 2007). Among Chinese-Americans, the results suggest that in addition to conveying realistic assessments of dangerousness and responsibility concerning the genesis of mental illness (Phelan, 2005), emphasizing that environmental factors play an equal role to genetic factors in causing mental illness and the relatively low absolute risk of heritability of most mental disorders (Kendler, 2001) may further reduce stigma. Such an anti-stigma approach differs markedly from current anti-stigma interventions for mental illness, which emphasize biogenetic psychoeducation (Jorm et al., 2005).

In sum, by identifying and testing a culture-specific threat that aids prediction of mental illness stigma among Chinese-American groups, we advance an empirical framework of culture and stigma. We intend this conceptualization to be further used to identify and test how stigma works across other conditions and other cultural contexts.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Extend a threat framework to include cultural components to explain cultural variations in stigma

Identify threat processes of genetic contamination that underlie elevated stigma among Chinese

Provide evidence from an experimental memory task to identify this culture-specific threat

Guide anti-stigma interventions by targeting culture-specific perceptions of threat among Chinese

Provide a novel framework to test how culture-specific forms of stigma work in other contexts

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by National Institutes of Mental Health Grant K01 MH73034-01, which was awarded to the first author, and the National Human Genome Research Institute grant HG01859, which was awarded to the last author. This study was also supported in part by the Asian American Center on Disparities Research (National Institute of Mental Health grant: P50MH073511). We also would like to thank Rebecca Franz for her help in coding data, and Charlene Chen for her help in reviewing literature. Finally, we would like to thank Rachel Han, Shijing Jiang and Rachel Chang for their help in formatting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lawrence H. Yang, Email: laryang@attglobal.net, lhy2001@columbia.edu, Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology/School of Public Health, Columbia University, 722 West 168th Street, Room 1610, NY, NY 10032, Phone: 917-686-0183, FAX: 212-342-5169.

Valerie Purdie-Vaughns, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, Columbia University.

Hiroki Kotabe, Ph.D. Student, Department of Psychology, University of Chicago.

Bruce G. Link, Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Sociomedical Sciences, School of Public Health/Columbia University

Anne Saw, Post-Doctorate, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles

Gloria Wong, PhD Candidate/Research Assistant, Department of Psychology, University of California, Davis

Jo C. Phelan, Professor, Department of Sociomedical Sciences/School of Public Health, Columbia University

References

- Allison PD. Missing data: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2002;55:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, López SR. The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist. 1993;48:629. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S, Duncan J, Brett M, Lawrence AD. Prefrontal cortical function and anxiety: controlling attention to threat-related stimuli. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:184–188. doi: 10.1038/nn1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J, Petty R. Social psychological procedures for cognitive response assessment: The thought-listing technique. In: Merluzzi T, Glass C, Genest M, editors. Cognitive assessment. Guilford Press; 1981. pp. 309–342. [Google Scholar]

- Chia R, Wuensch K, Childers J, Chuang C. A comparison of family values among Chinese, Mexican, and American college students. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1994;9:249–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, Diwan SL, Penn DL. Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27:219. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Lurie BD, Goldman HH, Slopen N, Medasani K, Phelan S. How adolescents perceive the stigma of mental illness and alcohol abuse. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:544–550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS, Moriarty D. Physical illness stigma and social rejection. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;34:67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tocqueville A. In: Democracy in America. Bowen F, translator. Cambridge: University Press; 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Deng R, Li J, Sringernyuang L, Zhang K. Drug abuse, HIV/AIDS and stigmatisation in a Dai community in Yunnan, China. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1560–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei X. From the soil: The foundations of Chinese society. University of California Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DB, Crandall CS. Dimensions of mental illness stigma: What about mental illness causes social rejection? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, Wong L. A cross-cultural comparison of British and Chinese beliefs about the causes, behaviour manifestations and treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry research. 2007;151:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Touchstone; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gray AJ. Attitudes of the public to mental health: a church congregation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2001;4:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh T, Duo L, Li H, Tomkins AM. Attitudes to HIV and HIV testing in high prevalence areas of China: informing the introduction of voluntary counselling and testing programmes. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:108–112. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.009704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Farina A, Hastorf A, Markus H, Miller D, Scott R. Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York: Freeman; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. The impact of beyondblue: The national depression initiative on the Australian public’s recognition of depression and beliefs about treatments. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:248–254. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Twin studies of psychiatric illness: An update. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:1005. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.11.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzrow MA. The mental health needs of today’s college students: Challenges and recommendations. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 2003;41:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books; 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Kleinman J. Face, favor and families: The social course of mental health problems in Chinese and American societies. Chinese Journal of Mental Health. 1993;6:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Chiu M, Tsang A, Chui H, Kleinman A. Stigmatizing experience and structural discrimination associated with the treatment of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1685. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee MT, Chiu MY, Kleinman A. Experience of social stigma by people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:153–157. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak WW, Cheung RY, Law RW, Woo J, Li PC, Chung RW. Examining attribution model of self-stigma on social support and psychological well-being among people with HIV+/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC. Geneticization of deviant behavior and consequences for stigma: the case of mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:307–322. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokoohi-Yekta M, Retish P. Attitudes of Chinese and American male students towards mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1991;37:192–200. doi: 10.1177/002076409103700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford C. The roads of Chinese childhood: Learning and identification in Angang. Vol. 97. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stangor C, Crandall CS, Heatherton T, Kleck R, Hebl M. The social psychology of stigma. 2000. Threat and the social construction of stigma; pp. 62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Ying YW, Lee PA. The Meaning of “being Chinese” and “being American” variation among Chinese American young adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2000;31:302–332. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review. 1985;92:548–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B, Perry RP, Magnusson J. An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:738–748. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Aiken LS. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Incorporated; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Woike B, Gershkovich I, Piorkowski R, Polo M. The role of motives in the content and structure of autobiographical memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:600. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonpat-Borja AJ, Yang LH, Link BG, Phelan JC. Eugenics, genetics, and mental illness stigma in Chinese Americans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y. Private life under socialism: Love, intimacy, and family change in a Chinese village, 1949–1999. Stanford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. Application of mental illness stigma theory to Chinese societies: synthesis and new direction. Singapore Medical Journal. 2007;48:977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Kleinman A. ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Phillips MR, Licht DM, Hooley JM. Causal attributions about schizophrenia in families in China: expressed emotion and patient relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:592. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Sia K, Lam J, Lam K. Culture, structural vulnerability and stigma: Deconstructing health disparities among Chinese immigrants with Psychosis. 2013. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Yiend J, Mathews A. Anxiety and attention to threatening pictures. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A. 2001;54:665–681. doi: 10.1080/713755991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.