Abstract

Epidemiological studies have linked exposure to traffic-related air pollutants to increased respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Evidence from human, animal, and in vitro studies supports an important role for oxidative stress in the pathophysiological pathways underlying the adverse health effects of air pollutants. In controlled-exposure studies of animals and humans, emissions from diesel engines, a major source of traffic-related air pollutants, cause pulmonary and systemic inflammation that is mediated by redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Assessment of human responses to traffic-related air pollution under realistic conditions is challenging due to the complex, dynamic nature of near-roadway exposure. Noninvasive measurement of biomarkers in breath and breath condensate may be particularly useful for evaluating the role of oxidative stress in acute responses to exposures that occur in vehicles or during near-roadway activities. Promising biomarkers include nitric oxide in exhaled breath, and nitrite/nitrate, malondialdehyde, and F2-isoprostanes in exhaled breath condensate.

Keywords: air pollution, traffic, oxidative stress, exhaled breath, airways, biomarkers

Introduction

Numerous epidemiological studies have associated exposure to ambient air pollutants with a range of adverse respiratory and cardiovascular health effects in different populations around the globe.1 Most of these studies have used ambient air monitoring data from central air monitoring stations to estimate the air pollution exposure in large populations. Ambient air pollution studies have focused primarily on particulate matter (PM) and ozone, two of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s “criteria pollutants.” More recently, a number of studies have linked traffic-related air pollutants to increased respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, including asthma incidence and exacerbation, and hospitalization and death due to myocardial infarction.2–4

Toxicological research on air pollution has established some degree of biological plausibility for the associations between exposure to air pollution and adverse health outcomes. Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between prooxidants (primarily reactive oxygen and nitrogen species) and antioxidant defenses, appears to play an important role in the toxicity of air pollutants.5 However, the degree to which traffic-related pollution contributes to oxidative stress in humans exposed to traffic under realistic exposure conditions is not known. Noninvasive techniques for measuring oxidative stress in human airways can help to translate the results of in vitro and animal studies to human experience with the goal of understanding how widespread exposures to traffic affect public health.

Driven by the epidemiological findings, toxicological studies have offered complementary insights into mechanisms and dose–response relationships that may link exposure to specific components or sources of traffic-related air pollutants to diverse outcomes. In addition to advancing causal understanding, the identification and characterization of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying associations between traffic exposure and health effects will be useful for predicting and evaluating effects on susceptible individuals. This research may ultimately lead to more-specific personal and public health interventions. Together, toxicological and epidemiological studies have provided evidence that air pollutants may cause pulmonary and cardiovascular toxicity through several modes of action, including local and systemic inflammation, as well as alterations in vascular physiology, coagulation factors, and autonomic function.1 Based on in vitro and animal studies, oxidative stress appears to be an important general mechanism within these pathways, but few studies to date have directly measured acute respiratory or systemic oxidative stress in humans following exposure to traffic or traffic-related pollutants.5

Controlled exposure studies of traffic-related air pollutants

The complexity of exposure to traffic-related air pollution presents a major challenge to understanding the mechanistic basis of the health effects of traffic exposure. Emissions from motor vehicle tail pipes include particles of varying size and chemical composition, gas-phase compounds that include oxides of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur, and thousands of organic compounds.6 The organic compounds, found in both the particle and gas phases, include aldehydes, alkanes, alkenes, aromatic hydrocarbons, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitro-PAHs, and heterocyclic compounds. Many of these compounds are regulated individually as toxic air pollutants. In addition to vehicle emissions, exposures near roadways include products of vehicle and tire wear, resuspended “road dust” particles, and ambient background pollutants. Moreover, many of the traffic-related air pollution components are physically and chemically reactive, resulting in a complex and dynamic aerosol that changes rapidly over short distances near roadways.7 Results from exposures of animals and humans to narrowly-defined, controlled conditions may have limited applicability to actual, real-world, human exposure to traffic-related air pollution.

Relatively few studies of animals or humans exposed to realistic traffic conditions are available. In animals, collected particles such as road dust and diesel exhaust particles have been shown to cause pulmonary and systemic oxidative stress and inflammation.8 However, in many of these studies, especially earlier ones, the particles were administered by intratracheal instillation or aspiration of a single, large dosage suspended in saline, which may have questionable relevance to exposure by inhalation. Recently, investigators have favored using inhalation exposure systems. Several studies have conducted controlled exposures to diluted, whole diesel exhaust among humans, the relevant species.9–13 A few studies have used experimental or quasi-experimental approaches to study human responses to roadside traffic14 or in-vehicle exposure while in traffic.15,16

Due to obvious ethical considerations, controlled exposure studies with human subjects must use short-term exposures at concentrations that may cause only mild, reversible effects. These studies are generally limited to the study of mechanisms underlying acute effects from at most a few brief exposure sessions, which may be different from mechanisms underlying effects of chronic exposure. However, many of the health outcomes associated with short-term increases in air pollution are acute clinical events, such as myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death, and asthma exacerbation. Controlled exposure studies can be especially useful for studying the acute subclinical effects that are likely to mediate these acute health outcomes. Short-term exposure studies can have particular relevance to traffic air pollutants, because higher-intensity, relatively brief exposures to near-roadway air pollutants occur during common activities such as walking, jogging, or bicycling along roadways and commuting.

Diesel exhaust and oxidative stress

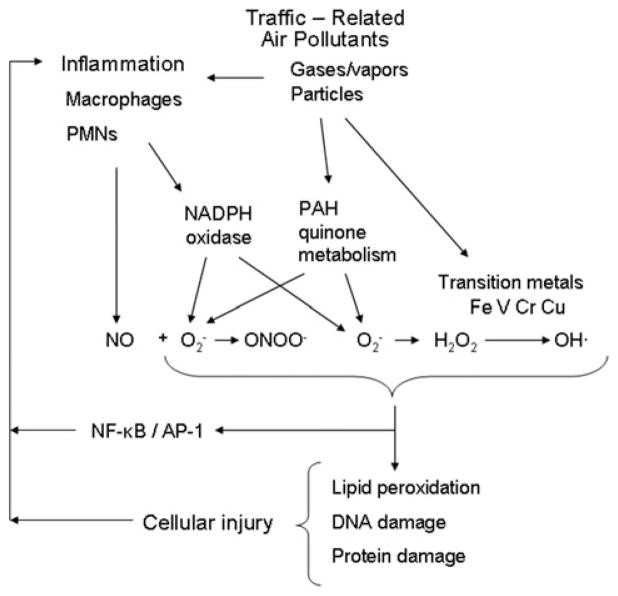

One practical approach to understanding the toxicological effects of complex traffic exposure is to study major sources of air pollutant emissions, namely gasoline and diesel engines. Partly owing to their greater contribution to particulate matter air pollution, there have been many more studies of the toxicity of diesel engine emissions than gasoline engines. Diesel exhaust is a major contributor to near-roadway air pollutants including particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and various volatile and semi-volatile products of incomplete fuel combustion.17 Diesel exhaust particles (DEPs) consist of an elemental carbon core with soluble and insoluble adsorbed components that can contribute to oxidative stress, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), PAH-quinones, and redox-active metals6 (Fig. 1). Components of DEP, such as transition metals and PAH-quinones, have demonstrated redox capability.18 In response to DEP, alveolar macrophages produce nitric oxide which can combine with superoxide anion to produce peroxynitrite, a potent oxidizing compound.19 (see Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Hypothesized pathways by which traffic-related air pollutants cause oxidative stress and cell damage. NO, nitric oxide; O2-, superoxide anion; ONOO-, peroxynitrite; H2O2, peroxide; OH·, hydroxyl radical; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine diphosphate; PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa beta; AP-1, activator protein-1; Fe, iron; V, vanadium; Cr, chromium; Cu, copper.

In controlled exposure studies, brief exposures to diesel exhaust have caused pulmonary inflammation in animals and humans (recently reviewed by Hesterberg and colleagues8). Controlled exposure to diesel exhaust caused increased bronchial hyper-reactivity among subjects with asthma.20 In a controlled “real-world” study in London, adults with asthma had decreased lung function and increased markers of lung inflammation (sputum myeloperoxidase and airway acidification) after a 2-h walk on Oxford Street, a heavy diesel traffic area, compared to a walk in Hyde Park.14 Interestingly, in another study, healthy subjects exposed to diesel exhaust in a chamber had more neutrophils in sputum after exposure than subjects with asthma.9 Systemic cardiovascular effects of diesel exhaust inhalation have ranged from increased circulating markers of inflammation and thrombosis to electrocardiographic ST segment depression indicating cardiac ischemia among men who had previously experienced myocardial infarction.11,21

Evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies supports the hypothesis that oxidative stress is a common mechanism through which diesel exhaust and other air pollutants cause adverse effects. In addition to diesel exhaust, diverse air pollutants, ranging from ozone to cigarette smoke, cause acute neutrophilic inflammation in the airways of animals and humans. Increases in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), appear to be instrumental in this initial inflammatory process. Oxidative stress is known to be an important regulator of IL-8 gene expression, which leads to recruitment of neutrophils.22 The upregulation of IL-8 and other proinflammatory cytokines by oxidative stress appears to occur via activation of redox-sensitive transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1). Pourazar and colleagues showed that NF-κB and AP-1 are activated in bronchial epithelial cells from healthy subjects exposed to diesel exhaust compared to filtered air.23 Bonvallot showed that DEP induced free radical generation in cultured human bronchial epithelial cells.24 The role of oxidative stress in the pulmonary toxicity of diesel exhaust is further supported by animal studies showing that diesel exhaust or DEPs cause oxidative damage to DNA in lung tissue25 and induce phase II antioxidant enzymes.26 Furthermore, antioxidant treatments protected against pulmonary inflammation after exposure to diesel exhaust.27 The strong influence of glutathione s-transferase genotypes on the enhancement of allergic responses after intranasal instillation of DEPs with ragweed pollen provided indirect evidence for the role of oxidative stress in these responses.28

Biomarkers of oxidative stress in exhaled breath

Noninvasive measurement of biomarkers in exhaled breath can facilitate greater understanding of the role of oxidative stress in airway responses to traffic emissions in humans. In some studies of air pollutants, including diesel exhaust, investigators have directly sampled airway lining fluid or pulmonary tissue via bronchoscopy.29,30 However, bronchoscopy is a costly procedure that has several disadvantages for air pollution studies. Foremost among its limitations are risks to subjects that may be difficult to justify in nontherapeutic trials, and impracticality for field studies. Sensitive analytical techniques allow the measurement of markers of oxidative stress directly in exhaled breath or in exhaled breath condensate (EBC). In contrast to bronchoscopy, these methods are noninvasive, require no medication, add no exogenous fluid to the airways, and can be repeated over short time periods. The ability to sample the airways frequently over short time periods may be especially helpful for dissecting the roles of exogenous and endogenous oxidant production based on their differential time courses (see Fig. 1).

In EBC, one can measure nonvolatile compounds such as ions, proteins, and DNA (see review by Hunt31). At present, EBC has limitations due to the highly dilute nature of the fluid and a lack of knowledge about precise anatomic sources. Exhaled breath condensate is highly diluted with condensed water vapor.31 The nonvolatile compounds in EBC are presumed to be derived from droplets of airway lining fluid (ALF) that escape epithelial surfaces via sheer forces or “popping” of alveoli.31 Breath biomarkers used in air pollution studies have included exhaled nitric oxide (eNO) and nitrite/nitrate and malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation, in EBC.

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), widely used as a marker of airway inflammation, may also be a useful marker for production of reactive nitrogen species that participate in oxidative stress.32 Variation in NO in exhaled breath is believed to arise primarily from the activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the bronchial epithelium, with some contribution from macrophages and lymphocytes.33 Several studies have shown associations between increased FeNO and increased air pollutant exposures. Among panels of subjects with asthma, FeNO increased with increased personal exposure to particulate matter and elemental carbon, a marker of diesel exhaust exposure.34,35 FeNO was associated with microenvironmental particulate matter exposure among elderly subjects taking trips on a diesel bus.15

Nitrite and nitrate are relatively stable products of NO that have been measured in exhaled breath condensate.36,37 Several studies have shown that increased nitrite and/or nitrate in EBC are associated with disease states such as asthma, COPD, and cystic fibrosis.38 To date, there are no published reports of changes in nitrite/nitrate in EBC following controlled exposure to DE or other traffic air pollutants. Like FeNO, nitrite/nitrate measurement in EBC may one day gain wider acceptance as markers of air inflammation and production of RNS. However, measurement of nitrogen oxides in EBC must overcome additional challenges that may ultimately limit their usefulness as biomarkers of oxidative stress in the respiratory tract. Some have reported that EBC nitrite is very variable within and between subjects. EBC nitrite appears to be susceptible to contamination from environmental or oral sources.31 Bacteria on the posterior surface of the tongue reduce nitrate, which is found in high concentrations in saliva, to nitrite. In a study comparing EBC obtained by oral breathing to EBC obtained via tracheostomy, the source of a large proportion of nitrite in EBC appeared to be the oral cavity.39

Products of lipid peroxidation are promising markers of oxidative stress in EBC, as well as in blood and urine.5 Higher F2-isoprostane concentrations have been reported in EBC from children with asthma compared to controls,32 but there are no reports of response to traffic-related air pollutants. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is one of the final products of lipid peroxidation that is generated mainly by arachadonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid.40 Romieu and colleagues recently reported an increase in MDA associated with increased PM and ozone among children with asthma in Mexico City.40 The increase in MDA was inversely correlated with lung function and correlated with IL-8 in nasal lavage fluid. Furthermore, there was a significant trend of increasing EBC MDA with increasing traffic counts at local intersections.

Conclusions

A growing body of epidemiological and experimental literature has specifically associated traffic-related air pollution with adverse respiratory and cardiovascular health outcomes. Oxidative stress appears to be a common mechanism involved in the various pathophysiological pathways implicated in studies of the toxic effects of air pollution in general, and traffic-related air pollution in particular. In comparison to ambient air pollutants, evaluation of the health risks presented by traffic-related air pollutants is challenging due to exposures to complex mixtures with physical and chemical characteristics that change rapidly over short distances from their sources. Studies of mechanisms involved in the acute effects of relatively short exposures to traffic-related air pollutants are especially relevant to common short-term exposure scenarios as well as the acute health outcomes that epidemiological studies have linked to these pollutants. Noninvasive measurement of oxidative stress markers in exhaled breath can help to translate findings from animal and in vitro studies to humans. Markers in breath may be especially useful for examining the mechanisms and kinetics of acute responses to naturalistic exposures to traffic-related pollutants, such as occur in vehicles and along roadways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIEHS ES005022 and ES135202, and USEPA R832144.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brunekreef B, Holgate ST. Air pollution and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Goldbohm S, Fischer P, Van Den Brandt PA. Association between mortality and indicators of traffic-related air pollution in the Netherlands: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360:1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jerrett M, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and asthma onset in children: a prospective cohort study with individual exposure measurement. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1433–1438. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonne C, et al. Traffic particles and occurrence of acute myocardial infarction: a case-control analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:797–804. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.045047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romieu I, Castro-Giner F, Kunzli N, Sunyer J. Air pollution, oxidative stress and dietary supplementation: a review. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:179–197. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US EPA. Health assessment document for diesel engine exhaust. National Center for Environmental Assessment and Office of Research and Development; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y, Levy J. Factors influencing the spatial extent of mobile source air pollution impacts: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hesterberg TW, et al. Non-cancer health effects of diesel exhaust: a critical assessment of recent human and animal toxicological literature. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009;39:195–227. doi: 10.1080/10408440802220603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenfors N, et al. Different airway inflammatory responses in asthmatic and healthy humans exposed to diesel. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:82–86. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00004603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvi S, et al. Acute inflammatory responses in the airways and peripheral blood after short-term exposure to diesel exhaust in healthy human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:702–709. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9709083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills NL, et al. Ischemic and thrombotic effects of dilute diesel-exhaust inhalation in men with coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1075–1082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peretz A, et al. Diesel exhaust inhalation elicits acute vasoconstriction in vivo. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:937–942. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordenhall C, et al. Airway inflammation following exposure to diesel exhaust: a study of time kinetics using induced sputum. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:1046–1051. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCreanor J, et al. Respiratory effects of exposure to diesel traffic in persons with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2348–2358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adar SD, et al. Ambient and microenvironmental particles and exhaled nitric oxide before and after a group bus trip. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:507–512. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laumbach RJ, et al. Acute changes in heart rate variability in Type II diabetics following a highway traffic exposure. JOEM. 2010;52:324–331. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181d241fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riedl M, Diaz-Sanchez D, Riedl M, Diaz-Sanchez D. Biology of diesel exhaust effects on respiratory function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.047. quiz 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia T, et al. Quinones and aromatic chemical compounds in particulate matter induce mitochondrial dysfunction: implications for ultrafine particle toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1347–1358. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, et al. Reactive oxygen species- and nitric oxide-mediated lung inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in wild-type and iNOS-deficient mice exposed to diesel exhaust particles. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A. 2009;72:560–570. doi: 10.1080/15287390802706330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordenhall C, et al. Diesel exhaust enhances airway responsiveness in asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:909–915. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17509090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tornqvist H, et al. Persistent endothelial dysfunction in humans after diesel exhaust inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:395–400. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-872OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li N, et al. Comparison of the pro-oxidative and proinflammatory effects of organic diesel exhaust particle chemicals in bronchial epithelial cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;169:4531–4541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pourazar J, et al. Diesel exhaust activates redox-sensitive transcription factors and kinases in human airways. Am J Physiol – Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L724–L730. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00055.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonvallot V, et al. Organic compounds from diesel exhaust particles elicit a proinflammatory response in human airway epithelial cells and induce cytochrome p450 1A1 expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:515–521. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.4.4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moller P, et al. Oxidative DNA damage in vitamin C-supplemented guinea pigs after intratracheal instillation of diesel exhaust particles. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;189:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wan J, Diaz-Sanchez D. Antioxidant enzyme induction: a new protective approach against the adverse effects of diesel exhaust particles. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19(Suppl 1):177–182. doi: 10.1080/08958370701496145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee A, et al. N-acetylcysteineamide (NACA) prevents inflammation and oxidative stress in animals exposed to diesel engine exhaust. Toxicol Lett. 2009;187:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilliland FD, et al. Effect of glutathione-S-transferase M1 and P1 genotypes on xenobiotic enhancement of allergic responses: randomised, placebo-controlled crossover study. Lancet. 2004;363:119–125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudell B, et al. Efficiency of automotive cabin air filters to reduce acute health effects of diesel exhaust in human subjects. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56:222–231. doi: 10.1136/oem.56.4.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudway IS, et al. An in vitro and in vivo investigation of the effects of diesel exhaust on human airway lining fluid antioxidants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423:200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt J, Hunt J. Exhaled breath condensate: an overview. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:587–596. v. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robroeks CM, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide and biomarkers in exhaled breath condensate indicate the presence, severity and control of childhood asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1303–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim KG, Mottram C. The use of fraction of exhaled nitric oxide in pulmonary practice. Chest. 2008;133:1232–1242. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delfino RJ, et al. Personal and ambient air pollution is associated with increased exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1736–1743. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mar TF, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma and short-term PM2.5 exposure in Seattle. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1791–1794. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balint B, Donnelly LE, Hanazawa T, et al. Increased nitric oxide metabolites in exhaled breath condensate after exposure to tobacco smoke. Thorax. 2001;56:456–461. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.6.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chladkova J, et al. Validation of nitrite and nitrate measurements in exhaled breath condensate. Respiration. 2006;73:173–179. doi: 10.1159/000088050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silkoff PE, et al. ATS workshop proceedings: exhaled nitric oxide and nitric oxide oxidative metabolism in exhaled breath condensate. Proc. 2006;3:131–145. doi: 10.1513/pats.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marteus H, Tornberg DC, Weitzberg E, et al. Origin of nitrite and nitrate in nasal and exhaled breath condensate and relation to nitric oxide formation. Thorax. 2005;60:219–225. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.030635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romieu I, et al. Exhaled breath malondialdehyde as a marker of effect of exposure to air pollution in children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:903–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]