Abstract

The initiation stage of mouse skin carcinogenesis involves induction of mutations in keratinocyte stem cells (KSCs), which confers a selective growth advantage allowing clonal expansion during tumor promotion. Targeted disruption of Stat3 in bulge region keratinocyte stem cells was achieved by treating K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice with RU486. Deletion of Stat3 prior to skin tumor initiation with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene significantly increased the number of apoptotic KSCs and decreased the frequency of Ha-ras codon 61 A182→T transversion mutations in this cell population compared with wild-type littermates. Targeted disruption of Stat3 in bulge region KSCs at the time of initiation also dramatically reduced the number of skin tumors (by ∼80%) produced following promotion with the phorbol ester, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. These results demonstrate that Stat3 is required for survival of bulge region KSCs during tumor initiation. Furthermore, these data provide direct evidence that bulge region KSCs are the primary targets for the initiation of skin tumors in this model system.

Keywords: Stat3, keratinocytes, stem cells, tumor initiation, skin carcinogenesis

Introduction

The two-stage model of mouse skin carcinogenesis has been used for many years for studying mechanisms of chemical carcinogenesis (1). Skin tumors arise [papillomas followed by squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs)] after a single topical application of an initiator [e.g., 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)] followed by repetitive applications of a tumor promoter [e.g., 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)] (2). During tumor initiation with DMBA, the ras gene (primarily Ha-ras) acquires mutations that confer a selective growth advantage to skin keratinocytes during tumor promotion (2). The end product of tumor promotion is the development of papillomas, a proportion of which undergo malignant conversion (1, 2). Considerable effort has been expended on identifying the target cells for tumor development in this model of epithelial carcinogenesis.

In normal tissue, stem cells are responsible for growth and repair by regenerating and providing “new” progeny cells, thus balanced stem cell proliferation is important for tissue homeostasis (3, 4). Stem cells are the slowest cycling cells that share similar properties of quiescence, self-renewal, and immortality with cancer stem cells (5, 6). These characteristics of stem cells suggest that cancer might arise from slowly cycling embryonic-like cells, rather than differentiated cells (7). Keratinoctye stem cells (KSCs) located in the bulge region of hair follicles are self-renewing cells that maintain hair growth and epidermal homeostasis by providing transit amplifying cells that differentiate into cutaneous lineage cells (8-10). Studies focusing on KSCs as the origin of skin tumors have suggested that KSCs, especially those in the bulge region of hair follicles, could be potential targets for skin carcinogenesis (11-14).

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) is one of a family of cytoplasmic proteins that participate in normal cellular responses to cytokines and growth factors as transcription factor (15-17). Upon activation by a wide variety of cell surface receptors, tyrosine phosphorylated Stat3 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus and modulates the expression of target genes that are involved in various physiological functions including apoptosis (e.g., Survivin and Bcl-xL), cell cycle regulation (e.g., Cyclin D1, and c-Myc), and tumor angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF) (17, 18). Studies have shown that constitutive activation of Stat3 is associated with a number of human tumors and cancer cell lines, including prostate, breast, lung, head and neck, brain, and pancreas, and its inhibition via various ways can suppress growth of cancer cells by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation (15, 16, 19, 20), suggesting that Stat3 may play a critical role in cancer cell proliferation and survival. Recent studies have also revealed that Stat3 plays an important role in maintaining the pluripotency in embryonic stem cells including survival (21-23). Furthermore, recent statistical analyses on expression and transcription factor-binding data have provided evidence that Stat3 is one of the significant core regulators in mouse embryonic stem cells, in addition to key stem cell regulators including Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog (24).

Our laboratory has demonstrated that Stat3 plays critical roles in both two-stage chemical- and UV-mediated skin carcinogenesis (25-31). In this regard, epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated activation of Stat3 occurrs in mouse epidermis following topical treatment of diverse classes of tumor promoters, including TPA, okadaic acid, and chrysarobin (32). Furthermore, constitutive activation of Stat3 is observed in both papillomas and SCCs induced by two-stage and UVB-mediated carcinogenesis in mice (27, 28). Consistent with these observations, epidermal specific Stat3-deficient mice were highly resistant to development of skin tumors induced by both two-stage as well as UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis regimens (29, 31). Further studies have shown more directly that Stat3 is required for both the initiation and promotion stages of carcinogenesis (32). Further evidence from these studies has suggested that Stat3 functions in maintaining survival of DNA-damaged keratinocytes including bulge region KSCs and by mediating cell proliferation necessary for the clonal expansion of initiated cells (reviewed in 25, 26).

To further investigate the potential role(s) of Stat3 during skin carcinogenesis, and more specifically its role in bulge region KSCs, we report for the first time generation of mice in which Stat3 is specifically disrupted in bulge region KSCs using an inducible system (33, 34). Here, we show that Stat3 is absolutely required for survival of bulge region KSCs during the initiation of skin tumors by DMBA. Furthermore, these data provide direct evidence that bulge region KSCs are the major targets for tumor initiation by DMBA in this model of epithelial multistage carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Generation of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice

The generation and characterization of K15.CrePR1 and Stat3fl/fl mice has been previously described (33, 34). K15.CrePR1 mice, originally generated on a B6SJL/F1 genetic background, were crossed for at least 10 generations onto the FVB/N genetic background prior to breeding with Stat3fl/fl mice. K15.CrePR1 mice were bred with Stat3fl/fl mice to generate mice hemizygous for the K15.CrePR1 transgene and homozygous for Stat3 floxed alleles. Female K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice at 7-8 weeks of age were used for the described experiments. The dorsal skin of each mouse was shaved 48 hours before treatment. All experiments were carried out with strict adherence to institutional guidelines for minimizing distress in experimental animals.

Preparation of skin wholemounts and detection of enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP)

To prepare wholemounts, mice were sacrificed and then dorsal skin was shaved with electric clippers and treated topically with hair removal cream for 1 minute prior to excision. The underlying fat and connective tissue were separated using scissors and the skin was cut into pieces (0.5×0.5 cm2). Whole skin pieces were placed on a glass slide and the localization of K15-EGFP was visualized using an inverted fluorescent microscope.

Analysis of epidermal apoptosis

Groups of mice (n = 3) were treated topically with 2 mg of RU486 or acetone for 5 consecutive days. One day after RU486 or acetone treatment, mice were treated with a single topical application of DMBA (100 nmol) or acetone (0.2 ml) on the dorsal skin and were sacrificed 24 hours later. Skin sections were stained with an antibody to the active form of caspase-3 (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) and then treated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and HRP-conjugated ABC reagent (BD Pharmingen, Los Angeles, CA). Apoptotic keratinocytes were counted microscopically in at least three nonoverlapping fields in sections from each mouse.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Skin samples were fixed in either formalin or 70% ethanol, embedded in paraffin and sectioned (5 μm). After deparaffinization, the slides were microwaved for 15 minutes, washed with 0.1 M ammonium chloride (NH4Cl)/PBS and incubated with 10% serum of host animal for secondary antibody/0.5% TritonX-100/1% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 40 minutes. Slides were then incubated for two hours at room temperature with K15 (LHK15; Neomarkers, Fremont, CA; diluted 1/50) or caspase-3 (AF835; R&D Systems, diluted 1/2000) antibodies diluted in 1% BSA/PBS. After two hours, slides were washed with 0.1M NH4Cl/PBS and incubated for 40 minutes with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (A11029; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; diluted 1/2000) or Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (A11037; Invitrogen; diluted 1/1000) secondary antibodies. After incubation slides were washed with 0.1 M NH4Cl/PBS and mounted using mounting medium with DAPI (Vectashield H-1200; Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). The sections were analyzed using a confocal microscope (Zeiss 510 META).

Isolation of bulge region KSCs

Bulge region KSCs were isolated from control and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice (n = 3-5) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis as previously described (35). After removal of fat and underlying subcutis, dorsal skins were incubated with dispase at 4°C overnight to separate epidermis from dermis. Dermis was digested with collagenase at 37°C for 1 hour. Hair follicles were isolated by centrifugation at 300 g for 5 minutes and at 52 g for 5 minutes. Hair follicle cells were trypsinized at 37°C for 10 minutes, successively filtered (100 μm, 35 μm) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and resuspended with DPBS/3% FBS. Cells were labeled with an α6 integrin-PE (CD49f) antibody (BD Pharmingen), a marker for basal keratinocytes (36) and a CD34-biotin antibody (eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA) an hematopoietic stem cell marker that specifically labels hair follicle bulge region KSCs (37), followed by labeling with streptavidin coupled to APC. Cell sorting and isolation were performed on a BD FACSAria SORP flow cytometer equipped with the BD FACSDiva™ 6.0 software (BD Biosciences). The purity of sorted populations was determined by post-sorting FACS analysis and generally exceeded 95%.

Mutation analysis

Groups of mice (n = 3) were treated topically with 2 mg of RU486 or acetone for 5 consecutive days. One day after RU486 or acetone treatment, mice were treated with a single topical application of DMBA (100 nmol) or acetone (0.2 mL) on the dorsal skin and sacrificed 1 or 10 days later. Genomic DNA was isolated and purified from bulge region KSCs (described above) using QIAGEN genomic-tip 20/G columns (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA). A mutation-specific PCR assay (38) was modified to detect Ha-ras codon 61 A182→T mutations in KSCs. Oligonucleotide primers specific for the normal and mutant Ha-ras gene were designed as follows: forward primer CD61-A, 5′-GGACTACTTAGA CACAGCAGGTCA-3′ (normal Ha-ras gene); forward primer CD61-T, 5′-GGACTA CTTAGACACAGCAGGTCT-3′ (mutant Ha-ras gene); reverse primer CD61-REV, 5′-CATGCAGCCAGGACCACTCTCATCG-3′. The mutant allele produces a 1.23 Kb amplification product.

Two-stage skin carcinogenesis

At eight weeks of age the dorsal skin of each mouse was shaved 48 hours prior to treatment. K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt (Group 1, n = 10) and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl (Group 2, n = 9) were treated topically with 2 mg of RU486 once daily for 5 consecutive days prior to initiation. Twenty-four hours after the last RU486 treatment mice were initiated with a single application of 25 nmol DMBA. Five weeks after initiation, both groups received twice-weekly applications of TPA at 6.8 nmol until the experiment was terminated. All compounds were topically applied in 0.2 mL acetone. The number and incidence of papillomas was determined weekly. Differences in tumor multiplicity and incidence were analyzed by the Mann Whitney U-test and the χ2-test, respectively.

Preparation of protein lysates and Western blot analysis

Eight to 10 papillomas were pooled, placed into ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer, incubated on ice for 10 minutes, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, re-thawed and centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was separated by electrophoresis on 8%-12% SDS/polyacrylamide gels. Separated proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto PVDF membranes and blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (TPBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with primary antibodies specific for Stat3, phospho-Stat3 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Blots were washed with TPBS and subjected to corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies against rabbit or mouse (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL), washed again with TPBS and protein expression was detected with ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL).

Results

Localization and specificity of K15 expression

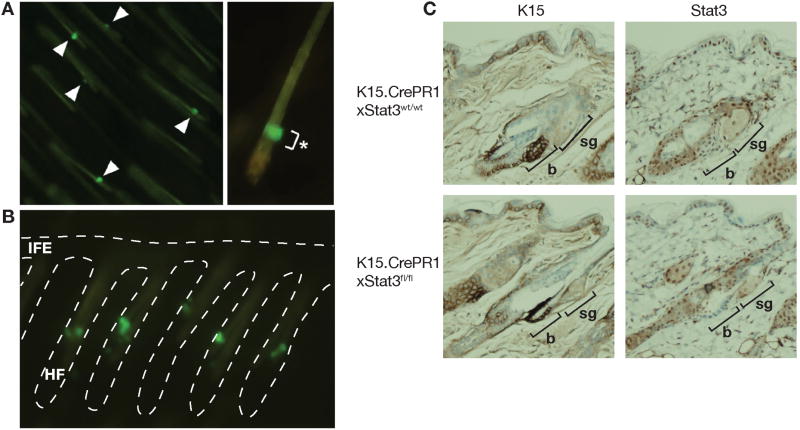

To further elucidate the functional roles of Stat3 in bulge region KSCs in skin carcinogenesis, inducible KSC-specific Stat3-deficient (K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl) mice were generated. To confirm the inducibility and specificity of K15 expression in these mice, we also generated K15.CrePR1 × Z/EG transgenic mice that express EGFP in bulge region KSCs following inducible Cre activation. K15.CrePR1 × Z/EG mice were then treated topically with the progesterone antagonist, RU486 (2 mg/mouse), once daily for 5 consecutive days. Following RU486 treatment, EGFP expression was observed in skin wholemounts. As shown in Figure 1A and 1B, EGFP expression was observed in highly restricted regions (i.e., bulge region) of hair follicles in K15.CrePR1 × Z/EG mice (Figure 1A). Further analysis of skin wholemounts revealed that EGFP expression could be detected in the bulge region of ≥ 90% of the hair follicles in a given field (Figure 1B). In Figure 1C, we examined expression of either K15 or Stat3 in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice after RU486 treatment. As shown in representative skin sections after staining, bulge region KSCs stained intensely for K15 in both genetic backgrounds as expected. In contrast, nuclear staining for Stat3 was observed in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt mice while in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice it was greatly reduced or absent. These data confirmed that the treatment protocol and specificity of K15 driven expression of Cre in bulge region KSCs was sufficient for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1. Specificity of the K15.CrePR1 inducible system.

(A and B) Immunofluorescence staining for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression in skin wholemounts from K15.CrePR1 × Z/EG transgenic mice following induction of Cre expression. RU486 (2 mg) was applied topically to the back skin of mice for five consecutive days. (A) Clear expression of EGFP in bulge region KSCs (left panel, arrow heads); specificity of expression is shown in the enlarged view of a single hair follicle (*, right panel). (B) Broken white line outlines hair follicles (HF) and interfollicular epidermis (IFE). Clear expression of EGFP is seen in bulge region KSCs in most of the HFs. (C) Representative sections of K15 and Stat3 staining in epidermis from K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice after 5 consecutive treatments (once daily) with RU486 (2 mg per mouse). Note markedly diminished Stat3 expression in bulge cells of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice treated with RU486 b: bulge region; sg: sebaceous gland

Keratinocyte stem cell-specific disruption of Stat3 inhibits skin tumor initiation

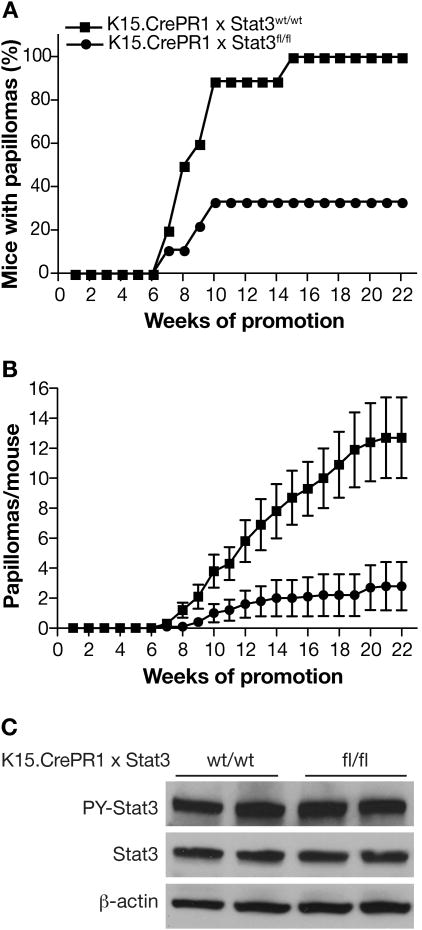

To investigate the impact of Stat3 deficiency in bulge region KSCs on skin tumor initiation and skin carcinogenesis, K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl and control mice were subjected to a two-stage chemical carcinogenesis regimen. K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice were treated with RU486 (2 mg/mouse) once daily for 5 days prior to initiation (Group 2). Control mice containing wild-type Stat3 alleles also received RU486 prior to initiation (Group 1). Tumor promotion with TPA was begun 5 weeks after initiation in both groups. K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice treated with RU486 before initiation showed a significant reduction in tumor development compared with the control group. In this regard, only 30% of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice developed papillomas after 22 weeks of promotion with TPA, whereas 100% of control mice developed papillomas (Figure 2A). More importantly, there was an ∼80% reduction in the average number of papillomas per mouse in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice at the end of the experiment (Figure 2B). These data indicate that deleting Stat3 specifically in bulge region KSCs dramatically inhibits tumor initiation by DMBA. Furthermore, the data indicate that a majority of skin tumors arise from bulge region KSCs.

Figure 2. Responsiveness of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice to two-stage skin carcinogenesis.

Groups of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt (n=10) and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl (n=9) mice were treated with RU486 (2 mg in 0.2 mL acetone) topically for 5 consecutive days. Twenty-four hours after the last treatment of RU486, mice received a single topical application of DMBA (25 nmol). Five weeks after initiation, both groups received twice-weekly applications of 6.8 nmol of TPA for the duration of the experiment. (A) Percentage of mice with papillomas and (B) Average number of papillomas per mouse (Mean ± SEM). (C) Western blot analysis of levels of Stat3 and phosphorylated Stat3 protein in skin papillomas obtained from K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice. Eight to ten papillomas were collected and pooled at the end of the study to generate protein lysates. Antibodies specific to Stat3 and phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) were used for analysis and β-actin was used to normalize protein loading.

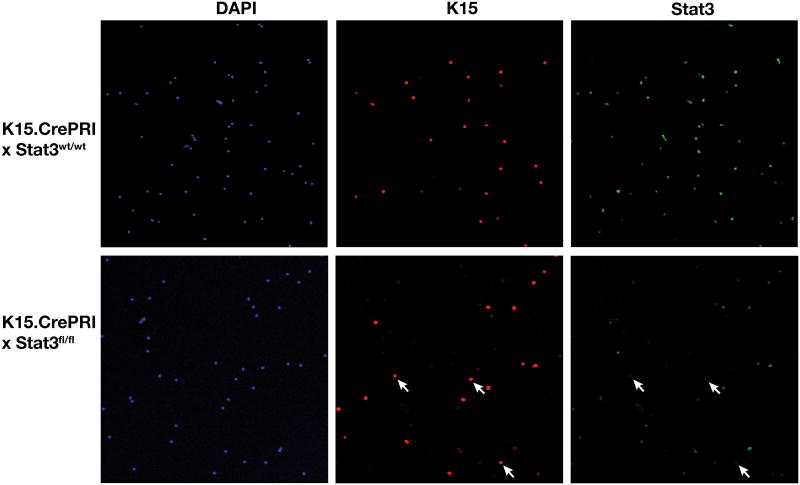

Western blot analysis of protein lysates from papillomas that arose in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice showed that both the levels of Stat3 and phosphorylated Stat3 were similar to that seen in papillomas from the control mice (Figure 2C). These data indicate that Stat3 is required for development of skin tumors in this model system. Furthermore, the presence of Stat3 in skin tumors from K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice suggests that either Stat3 deletion in bulge region KSCs is not complete and/or that some skin tumors arise from another stem cell compartment, as has been suggested by others (5, 39, 40). Figure 3 shows that within the population of hair follicle cells that express K15 only a portion appear to have significant deletion of Stat3, as assessed by immunofluorescence staining. These data suggest that the overall efficiency of Stat3 deletion is less than 100% and may explain why some tumors arose in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice.

Figure 3. Efficiency of the K15.CrePR1 inducible system on Stat3 deletion in bulge region KSCs of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice.

Groups of mice (n = 3) were treated topically with 2 mg of RU486 or acetone for 5 consecutive days. One day after RU486 treatment, hair follicle cells were isolated and loaded into the slide chamber for cytospin. Cells isolated by cytospin were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with antibodies against K15 (red) and Stat3 (41). DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies for K15 and Stat3, respectively. Slides were mounted using mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Fluorescent images were analyzed on a confocal microscope (Zeiss 510 META). Note that some of the cells isolated from K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice are positive for K15 but negative for Stat3 after inducible deletion (arrows).

Stat3 deletion in bulge region KSCs increases DMBA-induced apoptosis

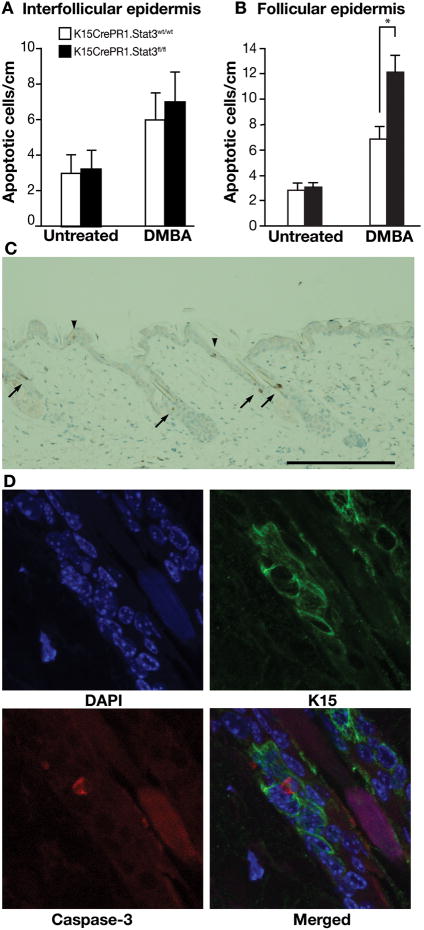

During tumor initiation, carcinogen-induced DNA damage may be repaired or damaged cells may undergo apoptosis. Both of these processes represent protective mechanisms against the development of tumors, through elimination of cells that might otherwise have the potential to acquire mutations. Cells that escape from these protective mechanisms are at risk for acquiring mutations that may confer a growth advantage and allow clonal expansion during the tumor promotion stage (reviewed in 1, 41). To examine the impact of Stat3 deficiency in bulge region KSCs on DMBA-induced apoptosis, K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice were treated topically once daily with RU486 (2 mg/mouse) for 5 days and 24 h later received DMBA treatment. Twenty-four h after treatment with DMBA, the number of apoptotic keratinocytes was determined by active caspase-3 staining in skin sections compared with similarly treated control mice. As shown in Figure 4A, there was no difference in the number of apoptotic keratinocytes in the interfollicular epidermis in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice compared to control mice following DMBA treatment. In contrast, topical application of DMBA to K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice resulted in a significant increase in the number of bulge region KSCs undergoing apoptosis compared to control (K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt.wt) mice (Figure 4B). The selectivity for apoptosis in bulge region KSCs of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice treated with DMBA can be seen in Figure 4C. In addition, Figure 4D provides confocal images demonstrating that cells undergoing apoptosis (detected by active caspase 3 staining; red) in hair follicles are the cells that express K15 (green).

Figure 4. Response of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice to DMBA-induced apoptosis.

Groups of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice (n=3/group) were treated with RU486 (2 mg in 0.2 mL acetone) topically for 5 consecutive days. Twenty-four hours after the last treatment of RU486, mice received a single topical application of DMBA (100 nmol) and were sacrificed 24 hours later. Skin sections were harvested and apoptotic cells were quantified by immunostaining for caspase-3. (A) Quantitation of caspase-3-positive cells per centimeter of interfollicular epidermis and (B) Quantitation of caspase-3-positive cells per centimeter of follicular epidermis in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt or K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice after DMBA treatment. *P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney U test. (C) Representative caspase-3 stain of epidermis from K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice following treatment with DMBA. Note that caspase-3-positive cells are found in the bulge region of hair follicles (arrows) and the interfollicular epidermis (arrowhead); scale bar: 20 μm. (D) Co-localization of K15 and active caspase-3 in bulge region KSCs of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl. Skin sections were stained with antibodies against K15 (green) and caspase-3 (red). DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining.

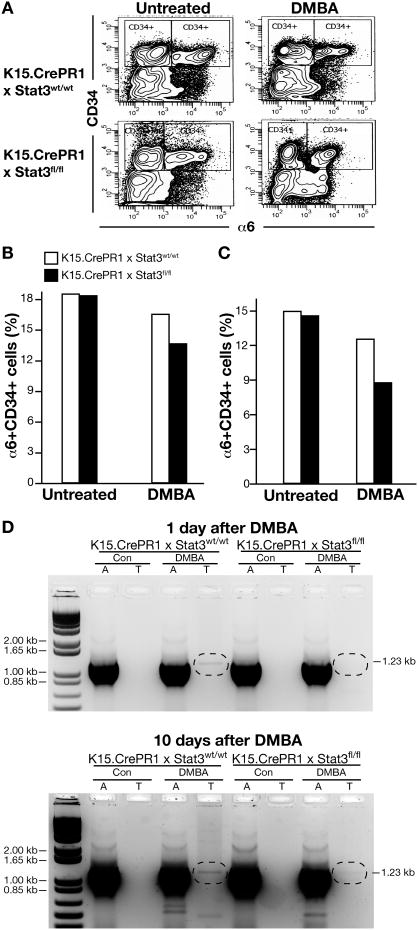

Stat3 deletion in bulge region KSCs reduces α6+CD34+ cells and cells with Ha-ras mutations

DMBA, a widely studied polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon requires metabolic activation to highly reactive diol-epoxides for its action as a skin tumor initiator and chemical carcinogen (reviewed in 1). These diol-epoxides bind covalently to DNA bases, especially deoxyadenosine, and form specific-DNA adducts that lead to mutations. More than 90% of the papillomas initiated by DMBA in the mouse skin model contain an activated Ha-ras gene with a single A to T transversion mutation at the second position of codon 61 (i.e., Ha-ras codon 61 A182→T mutation) (1, 41, 42). The increased apoptosis in bulge region KSCs of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice as shown in Figure 4 suggested that Stat3 deletion in bulge region KSCs would lead to a reduction in frequency in Ha-ras mutations if these cells represented the target cell population. To investigate this further, we determined the number of bulge region KSCs isolated from hair follicles using FACS analysis. In addition, we examined the frequency of Ha-ras codon 61 (A182→T) mutations in this population of cells. Bulge region KSCs express high levels of α6-integrin, a proliferation-associated cell surface marker for basal keratinocytes (40, 43). In addition, these cells express the hematopoetic stem cell marker CD34, a specific cell surface marker for bulge region KSCs (37). As shown in Figure 5, there was a reduction in the percentage of α6+CD34+ (including both α6low and α6high populations) in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice 24 h after treatment with either 100 or 1000 nmol DMBA (Figures 5A, B and C, respectively). Notably, Ha-ras codon 61 A182→T mutations were detected in α6+CD34+ hair follicle cells one day after treatment of control mice with DMBA (Figure 5D). In contrast, the Ha-ras codon 61 mutant band was significantly reduced at this time point in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice. Similar observations were obtained when cells were isolated at 10 d after treatment with DMBA (Figure 5D). Collectively, these data demonstrate that Stat3 deletion in bulge region KSCs leads to a loss of α6+CD34+ keratinocytes and a decrease in the number of these cells with signature Ha-ras mutations induced by DMBA. These data provide a mechanistic explanation for the dramatic reduction in tumor initiation seen in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice (see again Figure 2).

Figure 5. Effect of Stat3 deletion on DMBA-induced apoptosis and Ha-ras mutations in bulge region keratinocyte stem cells (KSCs).

Groups of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice (n=3/group) were treated with RU486 (2 mg in 0.2 mL acetone) topically for 5 consecutive days. Twenty-four hours after the last treatment of RU486, mice received a single topical application of DMBA and were sacrificed 24 hours later. (A) Hair follicle cells were isolated and labeled with antibodies for both α6 integrin and CD34. α6+CD34+ cells were then sorted by FACS analysis. Quantification of bulge region KSCs following FACS analysis in mice that received either (B) 100 nmol or (C) 1,000 nmol of DMBA. (D) Analysis of Ha-ras codon 61 A182→T mutations in genomic DNA isolated from bulge region KSCs of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl and K15.CrePR1 × Stat3wt/wt mice (n=3-5/group) after treatment with RU486 followed by DMBA (100 nmol). Control (CON) groups for each genotype received acetone only. Mice were sacrificed either 1 day or 10 days after treatment. An ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel separating the 1.23 kb PCR amplication product is shown with a 1 kb DNA ladder in Lane 1. Normal codon, lanes marked “A” and mutant codon, lanes marked “T”.

Discussion

As noted in the Introduction, recent studies from our laboratory using skin-specific gain and loss of function Stat3 transgenic mice have provided evidence that Stat3 has critical roles in both chemically- and UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis (29-31). Based on these studies, we hypothesized that Stat3 was required for survival of DNA damaged keratinocytes, especially bulge region KSCs during the initiation of skin tumors. In the current study, we provide direct evidence that Stat3 is required for survival of DNA damaged KSCs located in the bulge region of hair follicles. In the absence of Stat3, bulge region KSCs are prone to undergo apoptosis following treatment with DMBA. This leads to a decrease in bulge region KSCs that have Ha-ras mutations and ultimately a dramatic inhibition of skin tumor initiation as assessed in a two-stage skin tumorigenesis assay. Finally, the current data provide strong evidence that bulge region KSCs are the primary targets for tumor initiation by DMBA in this model of epithelial multistage carcinogenesis.

As shown in Figure 4, DMBA-induced apoptosis was significantly increased in the epidermis of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice after inducible deletion of Stat3 in bulge region KSCs. Close examination of skin sections stained for active caspase-3 revealed that the increase in apoptotic cells of K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl treated with RU486 was localized to the bulge region of the hair follicles. This was further confirmed by showing that the number of α6+CD34+ cells (i.e., including both α6low and α6high populations) was reduced following DMBA treatment and through co-localization of K15 staining with active caspase-3 staining. Stat3 is known to regulate a number of antiapoptotic genes, such as Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and survivin, leading to enhanced cell survival (44, 45). Our previous studies have suggested that one or more of these Stat3-regulated genes may be responsible for protecting DNA damaged bulge region KSCs. In this regard, recent studies using skin-specific Bcl-xL-deficient mice have shown a partial role of Bcl-xL in the protection of bulge region KSCs against DMBA-induced apoptosis in vivo (46). In addition, Stat3-mediated regulation of survivin expression and subsequent regulation of Oct-4, a POU homeobox transcription factor, has been shown to protect embryonic stem cells from stress related apoptosis (47). Furthermore, elevated expression of survivin in bulge region KSCs may confer protection from anoikis (48).

Evidence has accumulated that KSCs are the targets for chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin (reviewed in 11). Cells with properties of KSCs are found at the base of epidermal proliferative units (EPUs) in the interfollicular epidermis and in the bulge region of the hair follicles (8). These properties include slow cycling, label retaining properties (e.g., with 3HTdr or BrdU) (the latter referred to as label retaining cells or LRCs) and high proliferative capacity (9, 49). Furthermore, bulge region KSCs were found to express the hematopoietic stem cell marker, CD34 (37). Characterization of α6+/CD34+cells from the bulge region confirmed that these cells were slow cycling, co-localized with LRCs and exhibited high proliferative capacity in culture (35, 37). Morris et al. also showed that LRCs, not pulse-labeled cells, can undergo mitosis and remain on the basal layer (13) implying that LRCs have an ability for clonal expansion during skin tumor promotion. In addition, Morris et al. demonstrated that LRCs could retain carcinogen-DNA adducts (9). Trempus et al. also reported that CD34 expression in KSCs is required for TPA-induced hair follicle stem cell activation and tumor formation via the two-stage carcinogenesis protocol (12). In addition to the bulge region KSC stem cell niche, Nijhoff et al. (50) recently identified a novel murine progenitor cell population localized to a previously uncharacterized region above the bulge region. Cells in this region react with antibodies to the thymic epithelial progenitor marker MTS24. MTS24 positive cells do not express CD34 or K15 but possess a high proliferative capacity similar to bulge region KSCs and may be derived from the latter (50). Furthermore, other stem/progenitor cells that do not express MTS24 or K15/CD34 may also reside in the same general region called the upper isthmus (51). The question of which stem/progenitor cells are the primary target population has remained controversial. However, recent data (11) has suggested that both bulge region KSCs as well as KSCs found in the interfollicular epidermis may contribute to skin tumor development. Our current data demonstrate that bulge region KSCs are the primary targets for the initiation of skin tumors by DMBA in mouse skin.

Another interesting aspect of our current study was the observation that A182 →T transversion mutations in the Ha-ras gene could be detected in bulge region KSCs (i.e., α6+CD34+ cells) as early as one day following DMBA treatment (Figure 5). Furthermore, analysis of α6+CD34+ cells isolated from K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice treated with RU486 followed by DMBA showed a significant reduction in the frequency of Ha-ras mutation at both 1 and 10 days after treatment with DMBA. Mutations in Ha-ras are believed to represent a tumor-initiating event for mouse skin carcinogenesis in this model system (reviewed in 1, 52, 53). Our current study demonstrates for the first time that distinct, carcinogen specific mutations can be detected in the Ha-ras gene of bulge region KSCs. Furthermore, in the absence of Stat3 there was a decrease in the frequency of Ha-ras mutations in bulge region KSCs due to loss of cells following DMBA-induced DNA damage. Overall, these data provide further support for the conclusion that bulge region KSCs are the primary targets for initiation of mouse skin tumors by DMBA.

In conclusion, through inducible deletion of Stat3 in bulge region KSCs, we provide strong evidence for its role in the initiation of skin tumors by the carcinogen DMBA. Furthermore, the mechanism involves control of survival of bulge region KSCs following DNA damage by reactive metabolites of DMBA that lead to mutations in Ha-ras. The current data also provide strong evidence that bulge region KSCs are the primary targets for tumor initiation in this model system. Overall, these studies suggest that targeting Stat3 in KSCs is a viable strategy for prevention of skin cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NCI grant CA76520 (to J. DiGiovanni), The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA16672, and The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center Grant ES07784. Funding as an Odyssey Fellow was supported by the Odyssey Program and The H-E-B Award for Scientific Achievement at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (to D. J. Kim).

References

- 1.DiGiovanni J. Multistage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;54:63–128. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abel EL, Angel JM, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J. Multi-stage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: Fundamentals and applications. Nature Protocols. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.120. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs E. Skin stem cells: rising to the surface. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:273–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan X, Owens DM. The Skin: A Home to Multiple Classes of Epithelial Progenitor Cells. Stem cell reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12015-008-9022-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez-Losada J, Balmain A. Stem-cell hierarchy in skin cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:434–43. doi: 10.1038/nrc1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang C, Ang BT, Pervaiz S. Cancer stem cell: target for anti-cancer therapy. Faseb J. 2007;21:3777–85. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8560rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trosko JE, Tai MH. Adult stem cell theory of the multi-stage, multi-mechanism theory of carcinogenesis: role of inflammation on the promotion of initiated stem cells. Contrib Microbiol. 2006;13:45–65. doi: 10.1159/000092965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotsarelis G. Epithelial stem cells: a folliculocentric view. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1459–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris RJ, Fischer SM, Slaga TJ. Evidence that a slowly cycling subpopulation of adult murine epidermal cells retains carcinogen. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3061–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris RJ. Keratinocyte stem cells: targets for cutaneous carcinogens. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:3–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI10508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kangsamaksin T, Park HJ, Trempus CS, Morris RJ. A perspective on murine keratinocyte stem cells as targets of chemically induced skin cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:579–84. doi: 10.1002/mc.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trempus CS, Morris RJ, Ehinger M, et al. CD34 expression by hair follicle stem cells is required for skin tumor development in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4173–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris RJ, Fischer SM, Slaga TJ. Evidence that the centrally and peripherally located cells in the murine epidermal proliferative unit are two distinct cell populations. J Invest Dermatol. 1985;84:277–81. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12265358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris RJ, Coulter K, Tryson K, Steinberg SR. Evidence that cutaneous carcinogen-initiated epithelial cells from mice are quiescent rather than actively cycling. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3436–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J, Jove R. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:2474–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bromberg J. Stat proteins and oncogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1139–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI15617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy DE, Darnell JE., Jr Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darnell JE., Jr STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–5. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, et al. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turkson J, Jove R. STAT proteins: novel molecular targets for cancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2000;19:6613–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I, Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115:281–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niwa H, Burdon T, Chambers I, Smith A. Self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells is mediated via activation of STAT3. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2048–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuda T, Nakamura T, Nakao K, et al. STAT3 activation is sufficient to maintain an undifferentiated state of mouse embryonic stem cells. Embo J. 1999;18:4261–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Q, Chipperfield H, Melton DA, Wong WH. A gene regulatory network in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim DJ, Chan KS, Sano S, Digiovanni J. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in epithelial carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:725–31. doi: 10.1002/mc.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sano S, Chan KS, Digiovanni J. Impact of Stat3 activation upon skin biology: A dichotomy of its role between homeostasis and diseases. J Dermatol Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sano S, Chan KS, Kira M, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is a key regulator of keratinocyte survival and proliferation following UV irradiation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5720–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan KS, Carbajal S, Kiguchi K, Clifford J, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated activation of Stat3 during multistage skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2382–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan KS, Sano S, Kiguchi K, et al. Disruption of Stat3 reveals a critical role in both the initiation and the promotion stages of epithelial carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:720–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI21032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan KS, Sano S, Kataoka K, et al. Forced expression of a constitutively active form of Stat3 in mouse epidermis enhances malignant progression of skin tumors induced by two-stage carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2008;27:1087–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DJ, Angel JM, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Constitutive activation and targeted disruption of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in mouse epidermis reveal its critical role in UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28:950–60. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kataoka K, Kim DJ, Carbajal S, Clifford J, DiGiovanni J. Stage-specific disruption of Stat3 demonstrates a direct requirement during both the initiation and promotion stages of mouse skin tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1108–14. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris RJ, Liu Y, Marles L, et al. Capturing and profiling adult hair follicle stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:411–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sano S, Itami S, Takeda K, et al. Keratinocyte-specific ablation of Stat3 exhibits impaired skin remodeling, but does not affect skin morphogenesis. Embo J. 1999;18:4657–68. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;118:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonnenberg A, Calafat J, Janssen H, et al. Integrin alpha 6/beta 4 complex is located in hemidesmosomes, suggesting a major role in epidermal cell-basement membrane adhesion. The Journal of cell biology. 1991;113:907–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trempus CS, Morris RJ, Bortner CD, et al. Enrichment for living murine keratinocytes from the hair follicle bulge with the cell surface marker CD34. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:501–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson MA, Futscher BW, Kinsella T, Wymer J, Bowden GT. Detection of mutant Ha-ras genes in chemically initiated mouse skin epidermis before the development of benign tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6398–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown K, Strathdee D, Bryson S, Lambie W, Balmain A. The malignant capacity of skin tumours induced by expression of a mutant H-ras transgene depends on the cell type targeted. Curr Biol. 1998;8:516–24. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bailleul B, Surani MA, White S, et al. Skin hyperkeratosis and papilloma formation in transgenic mice expressing a ras oncogene from a suprabasal keratin promoter. Cell. 1990;62:697–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90115-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hennings H, Glick AB, Greenhalgh DA, et al. Critical aspects of initiation, promotion, and progression in multistage epidermal carcinogenesis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1993;202:1–8. doi: 10.3181/00379727-202-43511a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guengerich FP. Metabolism of chemical carcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:345–51. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tani H, Morris RJ, Kaur P. Enrichment for murine keratinocyte stem cells based on cell surface phenotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:10960–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grad JM, Zeng XR, Boise LH. Regulation of Bcl-xL: a little bit of this and a little bit of STAT. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12:543–9. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gritsko T, Williams A, Turkson J, et al. Persistent activation of stat3 signaling induces survivin gene expression and confers resistance to apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:11–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim DJ, Kataoka K, Kiguchi K, Connolly K, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Targeted disruption of Bcl-xL in mouse keratinocytes inhibits both UVB- and chemical-induced skin carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2009 doi: 10.1002/mc.20527. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo Y, Mantel C, Hromas RA, Broxmeyer HE. Oct 4 is Critical for Survival/Antiapoptosis of Murine Embryonic Stem Cells Subjected to Stress. Effects Associated with STAT3/Survivin. Stem Cells. 2007 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marconi A, Dallaglio K, Lotti R, et al. Survivin identifies keratinocyte stem cells and is downregulated by anti-beta1 integrin during anoikis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:149–55. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bickenbach JR, Mackenzie IC. Identification and localization of label-retaining cells in hamster epithelia. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82:618–22. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12261460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nijhof JG, Braun KM, Giangreco A, et al. Development. Vol. 133. Cambridge, England: 2006. The cell-surface marker MTS24 identifies a novel population of follicular keratinocytes with characteristics of progenitor cells; pp. 3027–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jensen UB, Yan X, Triel C, Woo SH, Christensen R, Owens DM. A distinct population of clonogenic and multipotent murine follicular keratinocytes residing in the upper isthmus. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:609–17. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balmain A, Ramsden M, Bowden GT, Smith J. Activation of the mouse cellular Harvey-ras gene in chemically induced benign skin papillomas. Nature. 1984;307:658–60. doi: 10.1038/307658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frame S, Crombie R, Liddell J, et al. Epithelial carcinogenesis in the mouse: correlating the genetics and the biology. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1998;353:839–45. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]