Abstract

Aberrant activation of PI3K/Akt signaling has been implicated in the development and progression of multiple human cancers. During the process of skin tumor promotion induced by treatment with the phorbol ester TPA, activation of epidermal Akt occurs as well as several downstream effectors of Akt, including the activation of mTORC1. Rapamycin, an established mTORC1 inhibitor, was used to further explore the role of mTORC1 signaling in epithelial carcinogenesis, specifically during the tumor promotion stage. Rapamycin blocked TPA-induced activation of mTORC1 as well as several downstream targets. In addition, TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and hyperplasia were inhibited in a dose-dependent manner with topical rapamycin treatments. Immunohistochemical analyses of the skin from mice in this multiple treatment experiment revealed that rapamycin also significantly decreased the number of infiltrating macrophages, T-cells, neutrophils, and mast cells seen in the dermis following TPA treatment. Using a two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol with DMBA as initiator and TPA as the promoter, rapamycin (5–200 nmol per mouse given topically 30 minutes prior to TPA) exerted a powerful anti-promoting effect, reducing both tumor incidence and tumor multiplicity. Moreover, topical application of rapamycin to existing papillomas induced regression and/or inhibited further growth. Overall, the data indicate that rapamycin is a potent inhibitor of skin tumor promotion and suggest that signaling through mTORC1 contributes significantly to the process of skin tumor promotion. The data also suggest that blocking this pathway either alone or in combination with other agents targeting additional pathways may be an effective strategy for prevention of epithelial carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Rapamycin, tumor promotion, mTORC1, epidermal hyperproliferation

Introduction

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is one of the most commonly altered pathways found in human tumors (1, 2). Although there is an established connection between deregulated Akt signaling and cancer development and progression, the downstream effectors mediating tumorigenesis have not been fully defined. Recent evidence has indicated that the mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR), a target of Akt, and subsequent downstream signaling may play a critical role in mediating at least some of the effects of aberrant Akt signaling during tumorigenesis (3–5). mTOR is a serine/threonine protein kinase that regulates cellular growth and proliferation by controlling protein synthesis (6). It is composed of two complexes: mTORC1, the rapamycin sensitive complex in which mTOR associates with Raptor and mLST8; and mTORC2, the rapamycin insensitive complex in which mTOR associates with Rictor, mLST8 and mSIN1 (7). mTORC1 phosphorylates downstream targets p70S6K and S6 ribosomal protein and also phosphorylates and inactivates the translational repressor, 4E- BP1, to regulate protein synthesis (8). mTORC2 is activated by receptor tyrosine kinases via an unknown mechanism and phosphorylates Akt at serine 473 (9).

Because of its central role in cellular growth and proliferation, mTOR is an attractive target for both treatment as well as prevention of cancer (10, 11). Rapamycin, an established mTORC1 inhibitor, has been shown to suppress tumorigenesis in a variety of xenograft models (12–14). In addition, rapamycin has been found to impair the growth of primary skin carcinomas induced by chronic exposure to UV (15). Rapamycin has also been shown to exhibit significant tumor suppressing effects on existing squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of the skin induced by the two-stage chemical carcinogenesis protocol (16) as well as display chemopreventive activity against carcinogen-induced lung cancer in A/J mice (17, 18). Rapamycin has also been evaluated in several transgenic models where it inhibited tumor progression. For example, in a mouse model for head and neck SCC (based on K-rasG12D expression and p53 loss in oral epithelium) rapamycin inhibited tumor progression and increased survival (19). In addition, rapamycin also decreased tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of erbB2 dependent human breast cancer (20) and inhibited tumor growth in a mouse model of prostate cancer (21).

During epithelial carcinogenesis in mouse skin, sustained activation of Akt has been found as tumors progress from papillomas to SCCs (22). Treatment of mouse skin with diverse tumor promoting stimuli leads to activation of Akt in epidermis as well as increased phosphorylation of several downstream effectors of Akt including mTOR, GSK3β, and BAD (23). These biochemical changes are sustained during the early stages of skin tumor promotion (23, 24). Collectively, these data suggested a possible role for one or more Akt downstream pathways in skin tumor promotion. In addition, mice overexpressing wildtype Akt1 (Aktwt) or a constitutively active form of Akt1 (Aktmyr) in the epidermis exhibited dramatically enhanced susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis (24). After treatment with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), Aktwt transgenic mice displayed prolonged activation of Akt as well as several downstream targets including mTORC1 as compared to nontransgenic mice. These data also suggested that the enhanced susceptibility to skin tumor promotion in Akt transgenic mice may be due, in part, to elevated mTORC1 signaling.

In the present study, we have assessed the ability of rapamycin to inhibit skin tumor promotion by TPA. Topical administration of rapamycin dramatically inhibited skin tumor promotion by TPA in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, rapamycin induced regression (and/or inhibited growth) of pre-existing papillomas. Topical treatment with rapamycin effectively blocked TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation as well as dermal inflammation. Biochemical studies demonstrated that rapamycin reduced TPA-induced epidermal signaling through the mTORC1 pathway. Rapamycin appeared to exert its potent inhibitory effects on skin tumor promotion by TPA through inhibition of mTORC1 signaling in keratinocytes leading to inhibition of epidermal proliferation. In addition, rapamycin inhibited TPA-induced inflammation that may also contribute to its potent anti-promoting effects. Together, these data show that rapamycin is a highly potent inhibitor of skin tumor promotion and support the hypothesis that signaling through mTORC1 contributes significantly to the process of skin tumorigenesis and tumor promotion. Blocking this pathway may be an effective strategy for prevention of epithelial carcinogenesis either alone or in combination with other agents that target additional signaling pathways activated during the process of tumor promotion.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA), Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), proteinase inhibitor cocktails, phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, anti-actin as well as anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO). TPA was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Rapamycin was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Antibodies against phosphorylated mTOR (Ser2448), mTOR total, phosphorylated Akt (Thr308 or Ser473), Akt total, phosphorylated p70S6K (Thr389), total p70S6K, phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (Ser240/244), and phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (Thr37/46 or Ser65) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc (Beverly, MA). Chemiluminescence detection kits were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Animals and Treatments

Female FVB/N mice in the resting stage of the hair cycle (7–9 weeks of age) were obtained from the National Cancer Institute and group housed for the duration of the study in all experiments. Biochemical Analyses. For multiple treatment experiment, groups of 6 mice each were dorsally shaved and treated twice weekly for two weeks (i.e. 4 treatments total) with acetone vehicle (0.2 mL), 6.8 nmol of TPA, 1000 nmol of rapamycin, or rapamycin (5 nmol–1000 nmol) in 0.2 ml acetone 30 min prior to 6.8 nmol of TPA. Mice were sacrificed 6 hours after final treatment and again pooled epidermal protein lysates were prepared. Histological analyses. For the evaluation of epidermal hyperplasia, labeling index (LI), and immune cell infiltration, the dorsal skin of mice (3 mice per group) was shaved, and then topically treated with 0.2 ml of acetone (vehicle), 6.8 nmol of TPA, 200 nmol of rapamycin or rapamycin (5 nmol –200 nmol) 30 min prior to TPA. Mice were treated twice weekly for 2 weeks and sacrificed 48 h after the last treatment. Mice received an i.p. injection of BrdU (100 µg/g body weight) in 0.9% NaCl 30 min prior to sacrifice. Dorsal skin samples were fixed in formalin,embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned. Sections were cut and stained with H&E, anti-BrdU, LY6G, S100A9, or CD3. Epidermal thickness and labeling index were determined as described previously (25). Immune cell infiltration was determined by the number of positive stained cells per 200 µm2 field (24 fields per slide). Two-stage skin carcinogenesis. Groups of 20 mice each were used for the two-stage skin carcinogenesis studies. The backs of mice were shaved 48 hours prior to initiation. All mice received a topical application of 25 nmol of DMBA in 0.2 ml acetone to the shaved dorsal skin. Two weeks after initiation, mice were treated topically with various doses of rapamycin (5 nmol – 200 nmol) in 0.2 ml acetone or vehicle (acetone) followed 30 minutes later by promotion with 6.8 nmol TPA in 0.2 ml acetone twice weekly until tumor multiplicity reached a plateau (25 weeks). All mice were weighed weekly during the course of the 25 week promotion period. Tumor incidence (percentage of mice with papillomas) and tumor multiplicity (average number of papillomas per mouse) were also recorded weekly for the duration of the study.

Preparation of epidermal lysates

After sacrifice, a depilatory agent was applied to the dorsal skin for 30 s and then removed under cold running water. The skin was then excised and the epidermal layer was removed by scraping with a razor blade into RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1% NP-40, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 and 2, proteinase inhibitor cocktail). The tissue was then homogenized using an 18-gauge needle. Epidermal scrapings from 6 mice were pooled to generate epidermal protein lysates for Western blotting. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 RPM for 15 min and either used immediately for Western analysis or snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80° until used.

Western Blot analyses

For analysis of Akt/mTOR activation, 50 µg of epidermal protein lysate was electrophoresed in 4–15% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% BSA in TBS with 1% tween (TTBS) and incubated overnight at 4°C with designated antibodies. After incubation, the membranes were washed 3 times for 10 min each in TTBS prior to incubation with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After additional washes (3 washes, 10 min each) to remove unbound secondary antibody, protein bands were then visualized using chemiluminescence detection (Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate, Rockford, IL) and quantitated using GeneSnap and GeneTools (Syngene, Frederick, MD).

Statistical Analyses

To compare epidermal thickness (µm), LI (% BrdU positive cells) and immune cell infiltration (number of positive cells per field) data were presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. For comparisons of epidermal thickness, LI and immune cell infiltration, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used (p≤0.05). For comparison of tumor incidence the χ2 test was used (p≤0.05). For comparison of tumor multiplicity data, the Mann-Whitney U-test was again used (p≤0.05).

Results

Effect of Rapamycin on Skin Tumor Promotion

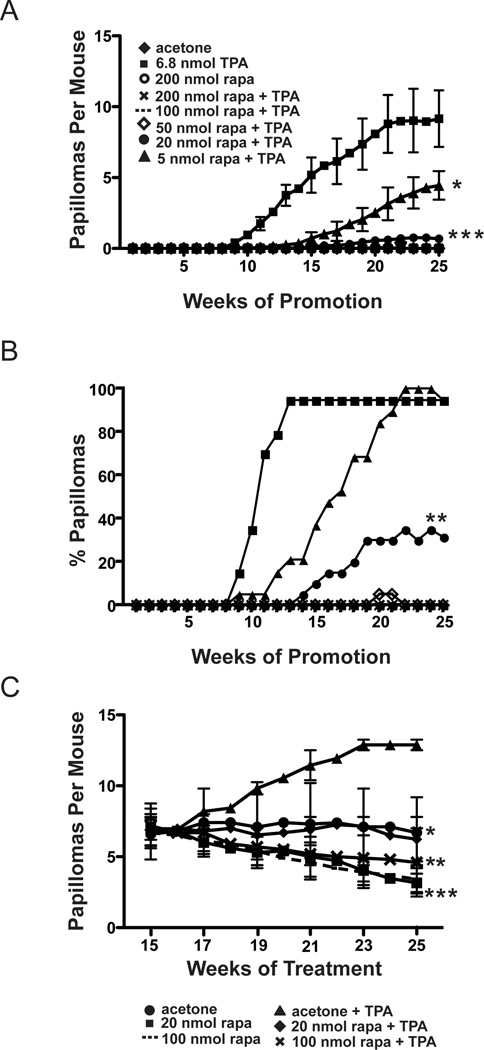

Two-stage skin carcinogenesis experiments were performed in wild type mice to evaluate the effect of rapamycin on skin tumor promotion by TPA. Groups of female FVB/N mice 7–8 weeks of age were initiated with 25 nmol of DMBA, and then two weeks later, treated topically with various doses of rapamycin (5 nmol–200 nmol) or acetone vehicle followed 30 minutes later by 6.8 nmol of TPA. All treatments were given twice weekly for the duration of the experiment (25 weeks). Tumor incidence (% of mice with papillomas) and tumor multiplicity (average number of papillomas per mouse) were measured weekly for each group. As shown in Figure 1A, rapamycin exerted a powerful anti-promoting effect. Treatment groups receiving topical application of 200, 100, or 50 nmol of rapamycin 30 minutes prior to application of TPA, had complete inhibition of papilloma development (Figure 1A). In addition, there was also a significant reduction in papilloma development in the groups receiving 20 nmol and 5 nmol doses of rapamycin compared to the DMBA-TPA only control group. In this regard, at week 25 a 92% inhibition of papilloma development was observed in the group receiving 20 nmol of rapamycin prior to TPA, and a 49% inhibition of papilloma development was observed in the group receiving 5 nmol of rapamycin prior to TPA (p<0.05, Mann-Whitney U test) (see again Figure 1A). No papillomas developed in the groups initiated with DMBA followed by twice weekly treatments with either acetone or 200 nmol of rapamycin. In addition, we did not observe a significant number of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in any of the groups at the end of the tumor experiment, consistent with previous studies from our laboratory that used an even higher initiating dose of DMBA (26). These studies showed that most SCCs developed in FVB/N mice after 25 weeks of promotion.

Figure 1. Effect of rapamycin treatment on skin tumor promotion by TPA.

Groups of 20 female FVB/N mice 7–8 weeks of age were initiated with 25 nmol of DMBA. Two weeks following initiation, mice were treated topically twice weekly with various rapamycin doses or acetone, followed by promotion with 6.8 nmol TPA for 25 weeks. A) Tumor multiplicity (average papillomas per mouse ±SEM). Differences in the average number of papillomas per mouse at 25 weeks between 20 nmol (●), 5 nmol (▲) rapamycin treated groups and the corresponding 6.8 nmol TPA (■) treated group were statistically significant (*P<0.05,***P<0.001, respectively, Mann-Whitney U Test). B) Tumor incidence (percent of mice with papillomas). Differences in tumor incidence at 25 weeks between the 20 nmol (●) rapamycin group and the 6.8 nmol TPA (■) group were statistically significant (**P<0.01,χ2-test). C) Female FVB mice 7–8 weeks of age were initiated with 25 nmol of DMBA and two weeks following initiation, promotion began with 6.8 nmol of TPA. Promotion was continued twice a week for 15 weeks. At 15 weeks mice were randomized and received either 100 nmol or 20 nmol of rapamycin or acetone either alone or followed by treatment with 6.8 nmol TPA. Differences in tumor multiplicity (average papillomas per mouse ± SEM) were statistically significant between the rapamycin treated groups and the 6.8 nmol TPA treated group. Acetone (●) and 20 nmol rapamycin + TPA (♦) groups (*P<0.05), 100 nmol rapamycin + TPA (✕)(**P<0.01), 20 nmol rapamycin (■) and 100 nmol rapamycin (---) (***P<0.0001); Mann-Whitney U Test.

Tumor latency was also affected in groups treated with 20 nmol and 5 nmol of rapamycin prior to treatment with TPA. The time to 50% incidence of papillomas in the TPA promotion control group was 10–11 weeks versus 16–17 weeks in the 5 nmol rapamycin treated group (Figure 1B). Mice in the 20 nmol rapamycin pretreated group reached only 32% tumor incidence as determined at week 25 (Figure 1B). Differences in tumor latency were statistically significant (p<0.05, χ2 test). These data clearly show that rapamycin was a potent inhibitor of TPA skin tumor promotion, dramatically reducing both tumor multiplicity and tumor incidence and altering latency in a dose-dependent manner. Note that a repeat experiment was conducted using similar doses of rapamycin for a duration of 23 weeks of promotion with TPA. The results were very similar to those shown in Figures 1A and 1B confirming the potent inhibitory effect of rapamycin on TPA promotion. In this repeat experiment, the time to 50% incidence of papillomas was 10–11 weeks in the TPA promotion control group versus 15–16 weeks in the 5 nmol rapamycin treated group. In addition, at 23 weeks of promotion, the 5 nmol rapamycin treated group had an 85% inhibition of papilloma development compared to the TPA control group (1.44±0.4 vs 9.75±0.5, respectively; p≤0.05). Furthermore, topical treatment with rapamycin had no effect on body weight gain in any of the experimental groups over the course of these experiments (data not shown).

Based on the data in Figures 1A and 1B showing that rapamycin dramatically inhibited the promotion of skin tumors an experiment was conducted to determine if topical treatments of rapamycin would inhibit growth of existing papillomas generated by the two-stage protocol. For this experiment, female FVB/N mice 7–8 weeks of age were initiated with 25 nmol of DMBA and promotion was begun two weeks later with 6.8 nmol of TPA. Promotion was continued twice-weekly for 15 weeks. At week 15, mice were randomized into groups that received topical applications of 100 nmol or 20 nmol of rapamycin alone, acetone alone, or rapamycin treatments (100 nmol and 20 nmol) 30 minutes prior to continued promotion with 6.8 nmol of TPA. All treatments continued until week 25. Tumor multiplicity and tumor incidence were determined each week. As shown in Figure 1C, topical treatment of rapamycin induced regression or inhibited growth of existing skin tumors. All groups receiving acetone or a dose of rapamycin with or without continued promotion with 6.8 nmol of TPA had statistically significant reductions in tumor multiplicity compared to the group that continued with just 6.8 nmol TPA treatments alone (p< 0.05, Mann Whitney U). At week 25 there was a 48% reduction of papilloma development in the acetone treated group compared to the 6.8 nmol treated group (Figure 1C). There was a 74% inhibition in the group receiving 100 nmol of rapamycin alone and a 67% inhibition in the group receiving 100 nmol of rapamycin prior to 6.8nmol of TPA (Figure 1C). There was a 75% inhibition of papillomas in the group receiving 20 nmol of rapamycin alone and a 49% inhibition in the mice receiving 20 nmol of rapamycin prior to treatment with 6.8 nmol of TPA (Figure 1C). There were no statistically significant differences in tumor incidence (data not shown). These data indicate that, in addition to dramatically preventing the formation of skin tumors, topically applied rapamycin inhibited growth and/or induced regression of existing papillomas even in the presence of continued TPA treatment.

Effect of Rapamycin on TPA-induced Epidermal Hyperproliferation

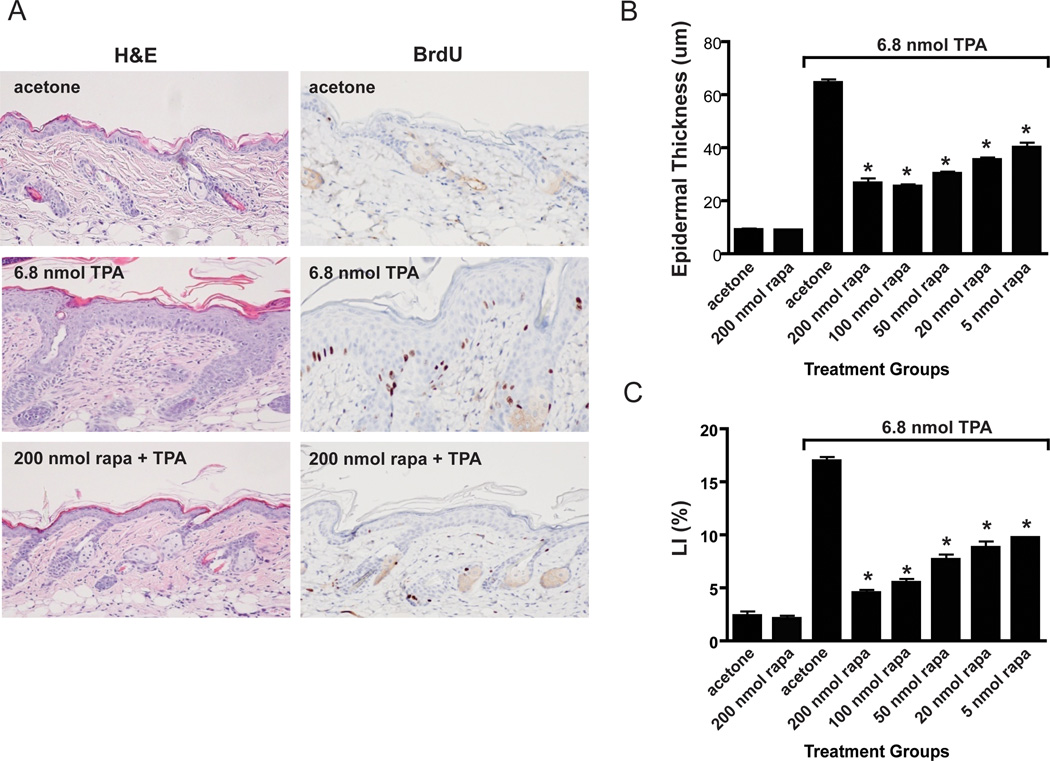

Due to the dramatic effect of rapamycin on skin tumor promotion by TPA, the possible effects of rapamycin on TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation were examined. For these experiments, groups of female FVB/N mice 7–8 weeks of age were treated topically with acetone (vehicle) or various doses of rapamycin (5–200 nmol) followed 30 minutes later by 6.8 nmol of TPA. This treatment regimen was continued twice-weekly for two weeks (i.e. 4 treatments total), and mice were sacrificed 48 hours after the final treatment. After sacrifice, the skin was removed and processed for histologic examination. Whole skin sections were evaluated for epidermal hyperplasia (as measured by epidermal thickness) and epidermal LI (as measured by BrdU incorporation). Figure 2A shows representative H&E and BrdU stained sections of dorsal skin after multiple treatments with either acetone, 6.8 nmol TPA, or 200 nmol of rapamycin followed by 6.8 nmol of TPA. Visual inspection of the sections revealed that rapamycin significantly reduced epidermal hyperplasia as well as LI when applied 30 minutes prior to TPA application. Quantitative analyses of the effect of rapamycin on TPA induced epidermal hyperplasia and LI are summarized in Figures 2B and 2C, respectively. All doses of rapamycin used (200, 100, 50, 20 and 5 nmol) produced statistically significant reductions in epidermal thickness and labeling index (LI) induced by TPA treatment (p<0.05, Mann Whitney U). These data demonstrate that rapamycin effectively blocked TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and that this effect may explain its ability, at least in part, to inhibit skin tumor promotion by TPA.

Figure 2. Effect of rapamycin treatment on TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation.

A) Representative sections of H&E and BrdU stains of dorsal skin collected from female FVB mice after multiple treatments with either acetone, 6.8 nmol TPA, or 200 nmol rapamycin (rapa) followed by 6.8 nmol TPA (twice a week for two weeks). B) Quantitative evaluation of the effects of rapamycin on TPA-induced epidermal hyperplasia (epidermal thickness). C) Quantitative evaluation of the effects of rapamycin on TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation (labeling index: LI). Values represent the mean ± SEM. (*P<0.05, Mann-Whitney U Test).

Effect of Rapamycin on Dermal Inflammatory Cell Infiltration

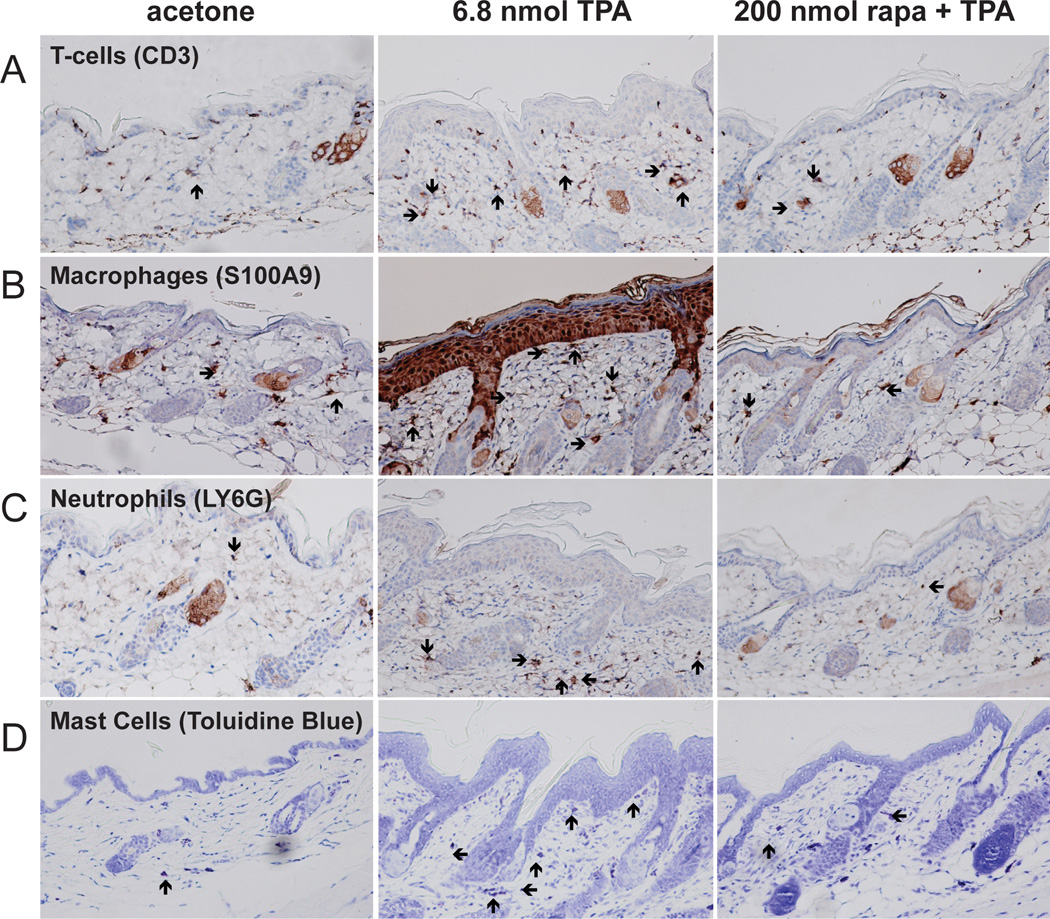

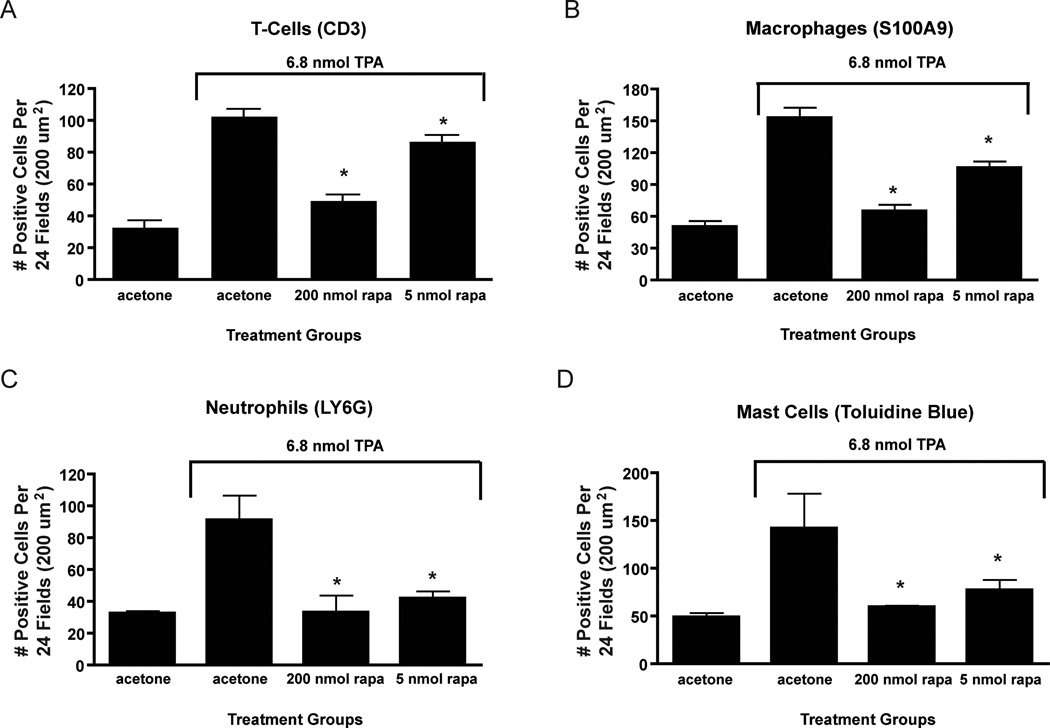

During the course of analyzing skin sections from rapamycin treated mice, a significant decrease in dermal inflammation and dermal inflammatory cell numbers was observed. Therefore, the effect of topical treatments of rapamycin prior to TPA on dermal inflammatory cell infiltration was further examined. For these experiments, groups of female FVB/N mice 7–8 weeks of age were treated topically with acetone (vehicle) or various doses of rapamycin (5–200 nmol) followed 30 minutes later by 6.8 nmol of TPA. This treatment regimen was continued twice-weekly for two weeks, and mice were sacrificed 48 hours after the final treatment for histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of various inflammatory cells. Whole skin sections were processed and stained for the following markers including CD3 (T-cells), S100A9 (macrophages), LY6G (neutrophils), and toluidine blue (mast cells). As noted above, visual inspection of skin sections revealed that rapamycin dramatically reduced infiltration of all 4 types of inflammatory cells as seen in Figure 3 for the 200 nmol dose of rapamycin (panels A–D, respectively). Quantitivative analyses of each cell type at two different doses of rapamycin (200 nmol and 5 nmol) are shown in Figure 4. Rapamycin at both doses presented produced statistically significant reductions in the number of all inflammatory cell types examined (p<0.05, Mann Whitney U test).

Figure 3. Effect of rapamycin treatment on TPA-induced dermal inflammation.

A) Representative sections of CD3 stained (T-cells) dorsal skin sections collected after multiple treatments of acetone, 6.8 nmol of TPA, or 200 nmol rapamycin (rapa) + TPA; B) Representative sections of S100A9 stained (macrophages) dorsal skin sections collected after multiple treatments with either acetone, 6.8 nmol of TPA, or 200 nmol rapamycin + TPA; C) Representative sections of LY6G stained (neutrophils) dorsal skin sections collected after multiple treatments with either acetone, 6.8 nmol of TPA, or 200 nmol rapamycin + TPA; D) Representative sections of toluidine blue stained (mast cells) dorsal skin sections collected after multiple treatments with either acetone, 6.8 nmol of TPA, or 200 nmol rapamycin + TPA. Arrows point to the indicated inflammatory cells in each panel.

Figure 4. Quantitative analysis of rapamycin’s effect on TPA-induced dermal inflammation.

A) Average number of positive cells per 24 fields (200 µm2) for CD3 stained sections in acetone, 6.8 nmol TPA, 200 nmol rapamycin + TPA, and 5 nmol rapamycin + TPA groups treated skins; B) Average number of positive cells per 24 fields (200 µm2) for S100A9 stained sections in acetone, 6.8 nmol TPA, 200 nmol rapamycin + TPA, and 5 nmol rapamycin + TPA groups treated skins; C) Average number of positive cells per 24 fields (200 µm2) for LY6G stained sections in acetone, 6.8 nmol TPA, 200 nmol rapamycin + TPA, and 5 nmol rapamycin + TPA groups treated skins; D) Average number of positive cells per 24 fields (200 µm2) for toluidine blue stained sections in acetone, 6.8 nmol TPA, 200 nmol rapamycin + TPA, and 5 nmol rapamycin + TPA groups treated skins. Values represent the mean ± SEM. (*P<0.05, Mann-Whitney U Test).

Effect of Rapamycin on mTOR Signaling in Epidermis

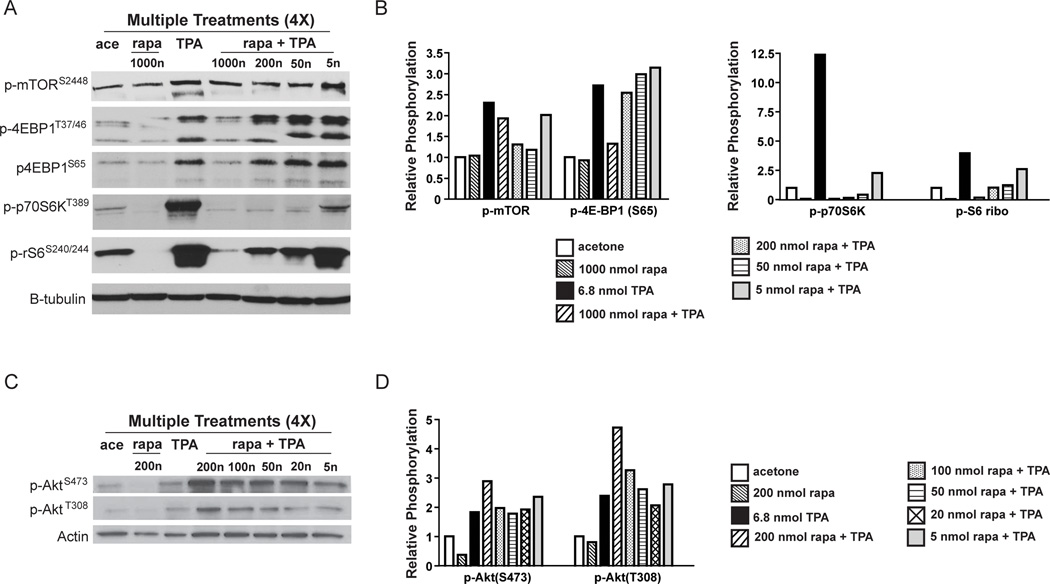

To further explore the potential mechanisms by which rapamycin inhibited TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and skin tumor promotion, experiments were conducted to evaluate changes in epidermal Akt and mTOR signaling pathways. For these experiments, female FVB/N mice 7–8 weeks of age were treated topically with either acetone or various doses of rapamycin (5–1000 nmol) 30 min prior to treatment with 6.8 nmol of TPA twice weekly for two weeks (total of 4 treatments). Note that a higher dose of rapamycin (1000 nmol) was used in initial Western blot experiments (Figure 5A). However, in subsequent experiments it was not used since doses of 50, 100 and 200 nmol rapamycin completely inhibited skin tumor promotion by TPA. Mice were sacrificed 6 hours after final treatment and epidermal protein lysates were prepared for Western blot analyses of Akt, mTOR and several mTORC1 downstream effector molecules. Topical application of TPA using this protocol led to phosphorylation of mTOR (Ser2448), and downstream effectors of mTORC1 including p70S6K (Thr389), p4E-BP1 (Ser65 and Thr37/46), and pS6-ribosomal (Ser240/244) (Figures 5A and 5B) as well as phosphorylation of Akt (Thr308, Ser473) (Figures 5C and 5D) as expected based on previous studies (23, 24). Although the phosphorylation of mTOR (Ser2448) was reduced somewhat at several doses of rapamycin, the most dramatic effects were seen on phosphorylation of p70S6K and S6-ribosomal protein (Figures 5A and 5B). In this regard, phosphorylation of the mTORC1 downstream effectors p70S6K (Thr389) and p-S6-ribosomal protein (Ser240/244) was decreased in the rapamycin treated groups in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, at the 1000 nmol dose, p4E-BP1 (Thr37/46, Ser65) was decreased as compared to the TPA treated group. Rapamycin given at a dose of 200 nmol in this multiple treatment regimen appeared to increase Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 as well as increase phosphorylation at the Thr308 site (again see Figures 5C and 5D). None of the other doses of rapamycin appeared to affect Akt phosphorylation at either site. Figures 5B and 5D show the quantitation of the Western blots shown in Figure5A and 5C, respectively. Similar results were obtained in a separate, independent experiment. The Western blots shown in Figures 5A and 5C are representative of both experiments. The quantitation shown in Figures 5B and 5D represent an average from both of these experiments. Collectively, these data suggest that treatment with rapamycin led to inhibition of TPA-induced mTORC1 downstream signaling, particularly through the p70S6K and S6-ribosomal protein pathway. Furthermore, at higher doses (≥ 200 nmol per mouse) rapamycin also appeared to increase Akt phosphorylation at Thr308.

Figure 5. Effect of rapamycin on TPA-induced mTOR signaling in mouse epidermis using a multiple treatment protocol.

Pooled protein lysates were prepared from the epidermal scrapings of FVB/N mice undergoing a multiple treatment regimen of acetone, 6.8 nmol TPA, 200 nmol rapamycin (rapa), or various doses of rapamycin (5–1000 nmol) prior to 6.8 nmol TPA. Western blot analyses were then conducted to examine activation of Akt and mTOR and downstream targets. A) Western blot of mTOR and downstream signaling molecules; B) Quantification of Western blots in panel A. C) Western blot analysis of Akt phosphorylation status; D) Quantification of Western blots in panel C These experiments were repeated with nearly identical results. Note that the quantitations shown in panels B and D represent an average of the two experiments whereas the Western Blots in panels A and C are from a single representative experiment.

Discussion

The current study was designed to examine the effects of rapamycin, an established mTORC1 inhibitor on tumor promotion during two-stage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. In addition, the effects of rapamycin on TPA-induced mTOR signaling pathways in epidermis as well as TPA-induced epidermal hyperplasia and proliferation were examined. Following topical application of diverse tumor promotors, including TPA, multiple growth factor signaling pathways are activated (27). The PI3K/Akt pathway is activated with subsequent phosphorylation of downstream targets mTOR, GSK3β, and Bad (23, 24). Targeting one or more of these pathways may be an effective way to inhibit tumor promotion. The current results demonstrate that topical treatment of mouse skin with rapamycin prior to TPA dramatically inhibited tumor promotion in a dose-dependent manner. In this regard, significant decreases in both tumor multiplicity as well as tumor incidence were observed (Figures 1A and 1B). Topical application of rapamycin to existing skin papillomas also induced regression and/or inhibited their growth (Figure 1C). Mechanistic studies revealed that rapamycin inhibited TPA-induced epidermal hyperplasia and hyperproliferation (Figure 2). In addition, rapamycin inhibited TPA-induced dermal inflammation as assessed by its effects on infiltration of several types of inflammatory cells. Finally, rapamycin effectively inhibited TPA-induced activation of mTORC1 signaling at doses that inhibited skin tumor promotion. Collectively, the data demonstrate that rapamycin is an extremely potent inhibitor of skin tumor promotion by TPA.

Recently, several laboratories including our own have demonstrated a critical role for Akt signaling in mouse skin carcinogenesis and tumor promotion. In this regard, overexpression of IGF-1 in the epidermis of transgenic mice induced epidermal hyperplasia, enhanced susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis and led to spontaneous skin tumor formation (25, 28). Biochemical alterations in the epidermis of these transgenic mice included elevated levels of PI3K and Akt activity and elevated phospho-mTOR and cell cycle regulatory proteins (28, 29). Topical application of LY294002, a PI3K specific inhibitor, not only directly inhibited these constitutive epidermal biochemical changes, but also inhibited IGF-1-mediated skin tumor promotion in a dose-dependent manner (29). Segrelles et al (22) reported sustained activation of epidermal Akt throughout two-stage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. More recent data published by this same group (30) and others (31, 32) have further confirmed the involvement of Akt-mediated cellular proliferation in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Transgenic mice overexpressing either Akt1wt or Akt1myr in the epidermis exhibited significantly enhanced susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis (24). Collectively, the data from two-stage carcinogenesis experiments using both IGF-1 and Akt transgenic mice further support the hypothesis that elevated Akt signaling can lead to increased susceptibility to epithelial carcinogenesis. The underlying mechanisms involved in Akt-mediated spontaneous tumorigenesis and the enhanced susceptibility to chemically induced carcinogenesis in mouse skin remain to be fully established, although studies performed in BK5.Aktwt and BK5.Aktmyr mice identified potential molecular targets through which Akt exerts its effects on tumorigenesis. In this regard, overexpression or constitutive activation of Akt led to enhanced epidermal proliferation that correlated with significant elevations of G1 to S phase cell cycle proteins, including cyclin D1 (24). In conjunction with these changes, a marked increase in signaling downstream of mTORC1 was observed suggesting that protein translation was also upregulated. As noted above, topical application of TPA leads to activation of Akt and mTORC1 signaling (23, 24). Furthermore, both IGF-1 and Akt transgenic mice were highly susceptible to TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation compared to wild-type mice. In addition, heightened mTORC1 activation is seen in these mice following TPA treatment. Overall, these data support the hypothesis that mTORC1 signaling may represent one of the important Akt downstream targets during skin tumor promotion. Recently, Lu et al (33) reported that overexpression of Rheb (an activator of mTORC1) in epidermis led to spontaneous skin tumor development and increased sensitivity to DMBA-induced tumorigenesis lending further support to this hypothesis.

As noted in the Introduction, several recent studies have reported that rapamycin effectively inhibited either development of tumors and/or inhibited growth of existing tumors in mouse models (12–21). In the mouse skin model, rapamycin (given i.p.) was shown to reduce the number of both early tumors as well as late tumors in protocols where tumors were already present on the backs of the mice at the time of treatment (16). In this particular study, the anti-tumor effect of rapamycin was attributed to its ability to induce apoptosis in tumor cells through reduced signaling downstream of mTORC1 (as assessed by levels of pS6) and reduced levels of the cell cycle proteins PCNA and cyclin D1. In studies related to UV skin carcinogenesis, de Gruij et al (15) reported that rapamycin (given in the diet) delayed the appearance and reduced the multiplicity of larger tumors (> 4mm). Our current data demonstrate that rapamycin was a remarkably potent inhibitor of skin tumor promotion by TPA and that this effect was related to inhibition of mTORC1 signaling in keratinocytes and inhibition of TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation. In addition, rapamycin treatment led to a significant reduction in dermal inflammation, which may have also contributed to its potent inhibitory effect.

As shown in Figure 5, topical treatment with rapamycin given 30 min prior to application of TPA inhibited TPA-induced epidermal mTORC1 signaling as assessed by decreased phosphorylation of mTOR (Ser2448) and the mTORC1 downstream targets p70S6K (Thr389) and pS6 ribosomal protein (Ser240/244). Rapamycin appeared to have less of an effect on 4E-BP1 phosphorylation with a reduction seen only at the highest dose of rapamycin tested (1000 nmol). This observation of lower inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation by rapamycin, is consistent with previously published data showing that rapamycin only partially inhibited phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 but fully inhibited phosphorylation of S6K (34, 35). Furthermore, Gingras et al (36) reported that phosphorylation at the Thr37 and Thr46 sites of 4E-BP1 by mTOR did not abolish its binding with eIF4E and that subsequent phosphorylation by other kinases is needed to release 4E-BP1 from eIF4E for translational activation. Thus, the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and subsequent requirements for release from eIF4E are complex. Our current data suggest that the effects of rapamycin on this mTORC1 signaling pathway may be less important than its effects on the p70S6K/S6 ribosomal downstream pathway in terms of inhibition of skin tumor promotion. It is interesting to note that rapamycin given at a dose of 200 nmol caused an increase in Akt phosphorylation at Thr308, which was not apparent at the lower doses (100 nmol, 50 nmol, 20 nmol and 5 nmol). Previous studies have shown an increase in Akt activity upon treatment with mTOR inhibitors due to a reduction of mTORC1 feedback inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway (37, 38). The increase in Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 seen with rapamycin treatment at the 200 nmol dose in the multiple treatment regimen may have been due to a similar inhibition of the mTORC1-dependent negative feedback loop. In contrast, phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 was not decreased with the highest dose of rapamycin used (again 200 nmol per mouse) (Figure 5) and may have been slightly increased. However in preliminary experiments we have observed a decreased phosphorylation of PRAS40 (Thr246), at the Akt specific phosphorylation site (data not shown). Sarbassov et al (39) recently reported that prolonged treatment with rapamycin inhibited mTORC2 assembly and Akt activity in vitro. Further work will be necessary to determine whether a multiple treatment regimen of higher doses of rapamycin (i.e. ≥ 200 nmol) prior to TPA affected the mTORC2 complex. Nevertheless, lower doses of rapamycin (i.e., 100, 50, 20 and 5 nmol) effectively inhibited TPA promotion of skin tumors and epidermal mTORC1 signaling without affecting phosphorylation of Akt at either site. Thus, inhibition of mTORC1 signaling appeared to be the main biochemical change associated with inhibition of skin tumor promotion at these lower doses of rapamycin.

Immunohistochemical analyses of the rapamycin treated skins revealed a significant decrease in the number of T-cells (Figure3A and 4A) and macrophages (Figure3B and 4B) present in the dermis. In addition, a significant reduction in neutrophils (Figure 3C, 4C) and mast cells (Figure 3D, 4D) was also observed. Granville et al. (17) reported no significant decreases in macrophage content of tumors from rapamycin treated mice compared to the tumors from the control (vehicle treated) mice. In addition, Amornphimoltham et al. also reported no differences in macrophage or T-cell content of skin tumors after rapamycin treatment (16). However, the experimental protocols used in these studies differed from that used in the current study. In this regard, the route of exposure to rapamycin was different in both of these previously published studies (i.p. injection). In addition both of these previously published studies evaluated inflammation following rapamycin treatment in pre-existing tumors. Overall, the current data suggest that rapamycin may exert anti-inflammatory effects earlier in the carcinogenesis process, especially during the early stage of tumor promotion and that this may have also contributed to its potent anti-tumor promoting activity.

In conclusion, rapamycin was a remarkably effective inhibitor of skin tumor promotion by TPA. On a molar basis, rapamycin is one of the most potent inhibitors of phorbol ester skin tumor promotion discovered to date. The ability of rapamycin to inhibit skin tumor promotion by TPA was associated with the inhibition of mTORC1 signaling in keratinocytes and inhibition of TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation. In addition, topical treatment with rapamycin significantly inhibited TPA-induced inflammation as assessed by a significant reduction in infiltrating T-cells, macrophages, neutrophils and mast cells. Together, the current data supports the hypothesis that elevated mTORC1 and activation of downstream signaling pathways is an important event during tumor promotion. In addition, the data supports the importance of mTORC1 as a potential target for prevention of epithelial cancers. Targeting this pathway either alone or in combination with other agents may be an effective strategy for the prevention of epithelial cancers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants CA037111 and CA129409. T. Moore was supported by NIEHS training grant ES007247.

References

- 1.Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowell JA, Steele VE, Fay JR. Targeting the AKT protein kinase for cancer chemoprevention. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2139–2148. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay N. The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–6422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang JX, Manning BD. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2009;37:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST0370217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, et al. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell. 2006;127:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia JA, Danielpour D. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in the management of urologic malignancies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1347–1354. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kopelovich L, Fay JR, Sigman CC, Crowell JA. The mammalian target of rapamycin pathway as a potential target for cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1330–1340. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amornphimoltham P, Patel V, Sodhi A, Nikitakis NG, Sauk JJ, Sausville EA, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin, a molecular target in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9953–9961. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Zhou J, Fan J, Qiu SJ, Yu Y, Huang XW, et al. Effect of rapamycin alone and in combination with sorafenib in an orthotopic model of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5124–5130. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namba R, Young LJ, Abbey CK, Kim L, Damonte P, Borowsky AD, et al. Rapamycin inhibits growth of premalignant and malignant mammary lesions in a mouse model of ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2613–2621. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Gruijl FR, Koehl GE, Voskamp P, Strik A, Rebel HG, Gaumann A, et al. Early and late effects of the immunosuppressants rapamycin and mycophenolate mofetil on UV carcinogenesis. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;127:796–804. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amornphimoltham P, Leelahavanichkul K, Molinolo A, Patel V, Gutkind JS. Inhibition of Mammalian target of rapamycin by rapamycin causes the regression of carcinogen-induced skin tumor lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8094–8101. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granville CA, Warfel N, Tsurutani J, Hollander MC, Robertson M, Fox SD, et al. Identification of a highly effective rapamycin schedule that markedly reduces the size, multiplicity, and phenotypic progression of tobacco carcinogen-induced murine lung tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2281–2289. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan Y, Wang Y, Tan Q, Haray Y, Yun TK, Lubet RA, et al. Efficacy of polyphenon E, red ginseng, and rapamycin on benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Neoplasia. 2006;8:52–58. doi: 10.1593/neo.05652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raimondi AR, Molinolo A, Gutkind JS. Rapamycin Prevents Early Onset of Tumorigenesis in an Oral-Specific K-ras and p53 Two-Hit Carcinogenesis Model. Cancer Research. 2009;69:4159–4166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu M, Howes A, Lesperance J, Stallcup WB, Hauser CA, Kadoya K, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a transgenic mouse model of ErbB2-dependent human breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2005;65:5325–5336. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blando J, Portis M, Benavides F, Alexander A, Mills G, Dave B, et al. PTEN deficiency is fully penetrant for prostate adenocarcinoma in C57BL/6 mice via mTOR-dependent growth. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1869–1879. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Perez P, Murga C, Santos M, Budunova IV, et al. Functional roles of Akt signaling in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:53–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J, Rho O, Wilker E, Beltran L, Digiovanni J. Activation of epidermal akt by diverse mouse skin tumor promoters. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:1342–1352. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segrelles C, Lu J, Hammann B, Santos M, Moral M, Cascallana JL, et al. Deregulated activity of akt in epithelial basal cells induces spontaneous tumors and heightened sensitivity to skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 2007;67:10879–10888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bol DK, Kiguchi K, Gimenez-Conti I, Rupp T, DiGiovanni J. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-1 induces hyperplasia, dermal abnormalities, and spontaneous tumor formation in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1997;14:1725–1734. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto T, Jiang J, Kiguchi K, Ruffino L, Carbajal S, Beltran L, et al. Targeted expression of c-Src in epidermal basal cells leads to enhanced skin tumor promotion, malignant progression, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4819–4828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rho O, Kim DJ, Kiguchi K, Digiovanni J. Growth factor signaling pathways as targets for prevention of epithelial carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2010 doi: 10.1002/mc.20665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiGiovanni J, Bol DK, Wilker E, Beltran L, Carbajal S, Moats S, et al. Constitutive expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 in epidermal basal cells of transgenic mice leads to spontaneous tumor promotion. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1561–1570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilker E, Lu J, Rho O, Carbajal S, Beltran L, DiGiovanni J. Role of PI3K/Akt signaling in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) skin tumor promotion. Mol Carcinog. 2005;44:137–145. doi: 10.1002/mc.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segrelles C, Moral M, Lara MF, Ruiz S, Santos M, Leis H, et al. Molecular determinants of Akt-induced keratinocyte transformation. Oncogene. 2006;25:1174–1185. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Affara NI, Schanbacher BL, Mihm MJ, Cook AC, Pei P, Mallery SR, et al. Activated Akt-1 in specific cell populations during multi-stage skin carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2773–2781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Affara NI, Trempus CS, Schanbacher BL, Pei P, Mallery SR, Bauer JA, et al. Activation of Akt and mTOR in CD34+/K15+ keratinocyte stem cells and skin tumors during multi-stage mouse skin carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2805–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu ZH, Shvartsman MB, Lee AY, Shao JM, Murray MM, Kladney RD, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin activator RHEB is frequently overexpressed in human carcinomas and is critical and sufficient for skin epithelial carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3287–3298. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman ME, Apsel B, Uotila A, Loewith R, Knight ZA, Ruggero D, et al. Active-site inhibitors of mTOR target rapamycin-resistant outputs of mTORC1 and mTORC2. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMahon LP, Choi KM, Lin TA, Abraham RT, Lawrence JC., Jr The rapamycin-binding domain governs substrate selectivity by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7428–7438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7428-7438.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gingras AC, Gygi SP, Raught B, Polakiewicz RD, Abraham RT, Hoekstra MF, et al. Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1422–1437. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang HH, Lipovsky AI, Dibble CC, Sahin M, Manning BD. S6K1 regulates GSK3 under conditions of mTOR-dependent feedback inhibition of Akt. Mol Cell. 2006;24:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, et al. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]