Abstract

Aim

Short-term psychological stress is associated with an immediate physiological response and may be associated with a transiently higher risk of cardiovascular events. The aim of this study was to determine whether brief episodes of anger trigger the onset of acute myocardial infarction (MI), acute coronary syndromes (ACS), ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, and ventricular arrhythmia.

Methods and results

We performed a systematic review of studies evaluating whether outbursts of anger are associated with the short-term risk of heart attacks, strokes, and disturbances in cardiac rhythm that occur in everyday life. We performed a literature search of the CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, and PsycINFO databases from January 1966 to June 2013 and reviewed the reference lists of retrieved articles and included meeting abstracts and unpublished results from experts in the field. Incidence rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated with inverse-variance-weighted random-effect models. The systematic review included nine independent case-crossover studies of anger outbursts and MI/ACS (four studies), ischaemic stroke (two studies), ruptured intracranial aneurysm (one study), and ventricular arrhythmia (two studies). There was evidence of substantial heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 92.5% for MI/ACS and 89.8% for ischaemic stroke). Despite the heterogeneity, all studies found that, compared with other times, there was a higher rate of cardiovascular events in the 2h following outbursts of anger.

Conclusion

There is a higher risk of cardiovascular events shortly after outbursts of anger.

Keywords: Anger, Cardiovascular disease, Case-crossover, Epidemiology

See page 1359 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu097)

Introduction

In addition to long-term risk factors for cardiovascular disease, there are several physical, psychological, and chemical triggers that are associated with a transiently higher risk of cardiovascular events.1 Several studies have reported that episodes of anger are associated with a transiently higher risk of myocardial infarction (MI),2–4 acute coronary syndrome (ACS),5,6 ischaemic7 and haemorrhagic stroke,8 and arrhythmia.9,10 However, since some of these studies were based on small sample sizes with few exposed cases, the results were often reported with low precision. Furthermore, there has been no systematic evaluation to compare the results and examine whether there is consistency across studies of the same cardiovascular outcome and whether the association is of similar magnitude across studies of different types of cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the literature to summarize the body of research testing the hypothesis that outbursts of anger trigger the onset of cardiovascular events and to summarize the literature on whether there are factors that modify the magnitude of the association.

Methods

We followed the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology11 protocol throughout the design, implementation, analysis, and reporting for this study.

Literature search

One person (E.M.) performed a literature search of the CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, and PsycINFO databases from January 1966 to June 2013 using the key words ‘anger’, ‘hostility’, ‘aggression’, ‘mental stress’, and ‘cardiovascular diseases’ without restrictions. We also reviewed the reference lists of retrieved articles and included meeting abstracts and unpublished results from experts in the field. We reviewed all articles with an abstract, suggesting that it was relevant. Studies were eligible for review if (i) the design was a cohort, a case–control, a self-controlled case series, or a case-crossover study; (ii) the investigators reported relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the association between outbursts of anger and MI, ACS, ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, and arrhythmia; and (iii) the investigators evaluated hazard periods for triggers occurring within 1 month before event onset. We considered articles in any language. We did not include studies that evaluated the impact of laboratory-induced anger on myocardial ischaemia and intermediate outcomes, such as blood pressure or cardiovascular reactivity, and we did not include case-crossover studies using a bidirectional sampling design12 since experiencing a cardiovascular event may alter exposure to anger episodes, resulting in reverse causation.

Data extraction

Using a standardized form, two readers (E .M. and E.P.) independently and in duplicate reviewed the list of identified articles and extracted data from selected articles, with disagreements adjudicated by a third reader (M.A.M.). For articles that did not include all of the necessary data for the meta-analysis, we contacted authors for additional information. The following details were recorded for each study: first author, year of publication, geographic location of study, whether the study was restricted to incident events, anger scale, hazard period, control period, the number of cases in the study, the number of cases exposed during the hazard period and the incidence rate ratio (IRR), and corresponding lower and upper 95% CI. If the studies used a cohort or case–control design, we recorded covariates included in the statistical models; if the study used a self-controlled case series or case-crossover design, we recorded covariates for time-varying confounding. When analyses of the same populations were reported more than once,2,4,13 the largest study4 was included in the meta-analysis. When case-crossover studies reported estimates using either a referent of usual frequency of anger episodes over several months or a referent of anger episodes at the same time on the prior day, we included the estimates based on the usual frequency data in our meta-analysis.

Assessment of study quality

We qualitatively assessed study quality by recording the training of interviewers, blinding of hypothesized hazard periods, and timing between the onset of the cardiovascular event and subsequent assessment of perceived anger.

Statistical analysis

We used DerSimonian and Laird14 inverse-variance-weighted random-effect models to pool the relative risks from individual studies. We evaluated heterogeneity across studies with the Cochrane Q statistic.15 We calculated the I2 statistic to quantify the proportion of between-study heterogeneity that is attributable to variability in the association rather than sampling variation; values of 25, 50, and 75% were considered to represent low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively.16,17 Using the Begg and Mazumdar18 and Egger et al.19 tests and visual inspection of a funnel plot,19 we explored the possibility of publication bias due to missing or different estimates from small studies with less precise estimates compared with larger studies with greater precision. We conducted stratified analyses to evaluate the influences of incident vs. recurrent events and MI vs. ACS, and we carried out sensitivity analyses excluding one study at a time to explore whether the results were driven by a single study. For ease of interpretation, we estimated the absolute risk of cardiovascular events associated with outbursts of anger of varying frequency for individuals at low (5%), medium (10%), and high (20%) 10-year risk of coronary heart disease,20 as previously described.21 The analyses were performed with Stata statistical software version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) using the metan package. All hypothesis tests were two-sided. P < 0.10 was considered indicative of statistically significant heterogeneity, and all other P-values were considered statistically significant at <0.05, two-sided.

Results

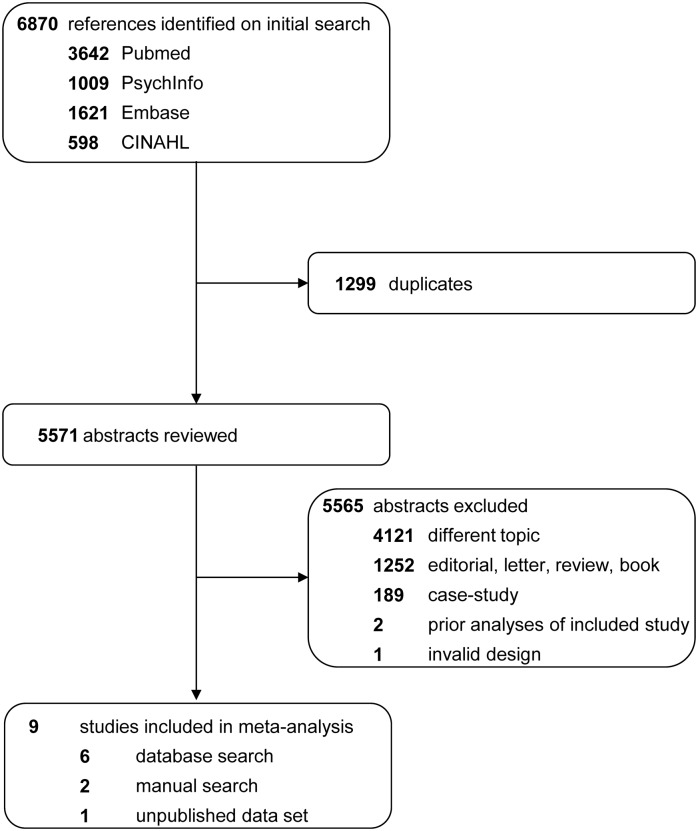

The literature search identified 6870 publications, and after excluding 1299 duplicates, an additional 5565 articles were excluded after the review of the title or abstract (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the eligible studies. The meta-analysis included nine independent case-crossover studies, including seven that were published between 1995 and 2013, a meeting abstract on anger as a trigger of arrhythmia10 and unpublished results of anger as a trigger of ischaemic stroke. Combined, there were 4546 cases of MI, 462 cases of ACS, 590 cases of ischaemic stroke, 215 cases of haemorrhagic stroke, and 306 cases of arrhythmia. The meta-analysis of anger outbursts as a trigger of cardiovascular events is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies included in a meta-analysis of short-term risk of cardiovascular events following episodes of anger.

Table 1.

Studies on anger outbursts as a trigger of cardiovascular events in the following 2 h

| First author, year, country | Outcome | Hazard period | Referent period | Anger measure (cut-off) | Total sample | Exposed cases, n (%) | Incidence rate ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mostofsky et al. (2013)4 USA | Myocardial infarction | 2 h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥5) | 3886 | 110 (2.8) | 2.4 (2.0–2.9) |

| Möller et al. (1999)3 Sweden | Incident myocardial infarction | 2 h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥5) | 660 | 10 (1.5) | 5.7 (3.0–10.6) |

| Strike et al. (2006)5 UK | Acute coronary syndrome | 2 h | Prior 6 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥3) | 253 | 44 (17.4) | 7.3 (5.2–10.2) |

| Lipovetzky et al.(2007)6 Israel | Incident acute coronary syndrome | 1st h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥4) | 209 | a | 6.2 (3.6–10.9) |

| 2nd h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥4) | 209 | a | 4.3 (2.2–8.6) | ||

| Koton et al. (2004)7 Israel | Ischaemic stroke | 2 h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥5) | 200 | 15 (7.5) | 7.60 (4.3–13.7) |

| SOS (unpublished) USA | Ischaemic stroke | 2 h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥5) | 390 | 6 (1.5) | 1.7 (0.8–3.5) |

| Vlak et al. (2011)8 the Netherlands | Ruptured intracranial aneurysm | 1 h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scalea | 215 | 2 (0.9) | 6.3 (1.6–25.0) |

| Lampert et al. (2002)9 USA | Ventricular arrhythmia | 0–15 min | Same day of the week and time of Day 1 week later | Hedges diary (≥3) | 107b | 17 (15.9) | 1.8 (1.0–3.2) |

| 15 min–2 h | Same day of the week and time of Day 1 week later | Hedges diary (≥3) | 107b | 14 (13.1) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | ||

| Albert et al. (2006)10 USA | Ventricular arrhythmia | 1 h | Prior 12 months | Onset Anger Scale (≥5) | 199 | 15 (7.5) | 3.2 (1.8–5.7) |

aInformation not available.

bA total of 107 confirmed ventricular arrhythmias requiring shock were reported by 42 patients. The 17 anger-associated shocks occurred in 14 patients, with 3 patients reporting 2 anger-associated shocks and 11 patients one each.

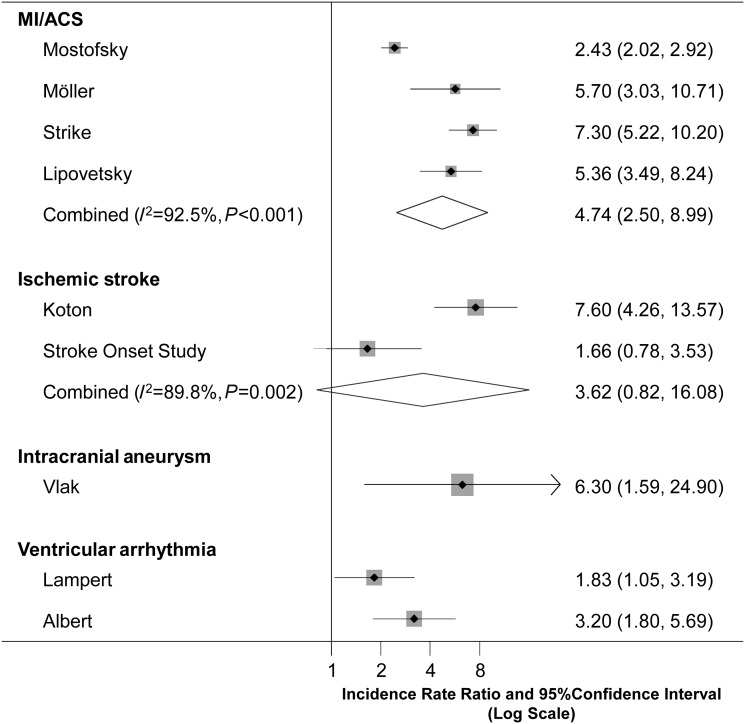

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the nine studies examining the short-term risk of cardiovascular events in the 2 h* following outbursts of anger. The solid vertical line indicates no association; the diamonds indicate the combined estimates. * = One study (Lipovetzky) reported separate estimates for each hour prior to MI onset. We meta-analyzed these two estimates and included this pooled estimate in our meta-analysis of MI/ACS.

There are several sources of between-study heterogeneity. Our systematic review includes that studies conducted in the USA,4,9,10 Sweden,3 England,5 Israel,6 and the Netherlands.8 One study6 asked about workplace anger outbursts, and all other studies asked about anger episodes at any time. All but one9 of the studies identified in our systematic review used the Onset Anger Scale,2 but they used different cut-offs to define exposure. In addition, the studies used different protocols for administering the questions regarding the usual frequency and timing of anger outbursts at each level: (i) some studies reported that they administered a structured interview3–7 by trained personnel,3,4 and other studies used a questionnaire completed by the patient;8,9 (ii) most studies reported that questions about anger outbursts were completed within hours9 or days3,4,6,7,9 of the index cardiovascular event, whereas in one study,8 two -thirds of the patients completed the questionnaire >2 weeks after their stroke; and (iii) most studies3,4,6,9 reported that in order to minimize recall bias, patients were not informed of the duration of the hypothesized hazard period, whereas one study8 reported that they specifically asked about anger outbursts during the pre-specified hazard period.

MI and ACS

Two studies3,4 examined as an endpoint and another two studies5,6 examined ACS as an endpoint; two studies were restricted to incident events,3,6 and two included incident and recurrent events.2,5 All four studies used the Onset Anger Scale2 with different cut-offs for defining exposure. One study6 reported separate estimates for each hour prior to MI onset, and the other studies3,5,22 reported a single estimate for the 2 h prior to MI onset. Therefore, we first meta- analysed the results for the first 2 h in the study with separate estimates6 and included this pooled estimate (RR = 5.36, 95% CI: 3.49–8.24) in our meta-analysis of the four studies on anger outbursts and MI/ACS. Based on the random -effect meta-analysis, there was a 4.74 (95% CI: 2.50–8.99; P < 0.001) times higher risk of MI or ACS in the 2 h following outbursts of anger compared with other times. There was evidence of heterogeneity between the four studies (Cochran Q test for heterogeneity: Q = 39.80, P < 0.001; I2 = 92.5%). Since there was high between-study heterogeneity, a pooled estimate may not be appropriate, but the results suggest that despite differences between studies, there is evidence of higher MI/ACS risk following episodes of anger.

The results were stronger for studies of incident events (IRR = 5.47, 95% CI: 3.83–7.80; Q = 0.02, P = 0.86; I2 = 0%) than for studies including both incident and recurrent events (IRR = 4.17, 95% CI: 1.42–12.26; Q = 31.96, P < 0.001; I2 = 96.9%) and higher for studies of ACS (IRR = 6.45, 95% CI: 4.80–8.99; Q = 1.24, P = 0.27; I2 = 19.1%) than studies of MI (IRR = 3.52, 95% CI: 1.54–8.06; Q = 6.47, P = 0.01; I2 = 84.5%). In sensitivity analyses excluding each study, the results were not meaningfully altered, though the pooled estimate was lower when we removed one study5 (IRR = 4.04, 95% CI: 2.13–7.66) and higher when we removed one study4 (IRR = 6.37, 95% CI: 5.00–8.13). The Begg (P = 1.00) and Egger regression tests (P = 0.21) and the funnel plot provided no evidence of substantial publication bias, but since we had a small number of studies, formal assessment of publication bias may not be appropriate.

Ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke

In addition to the one published study7 of anger outbursts and ischaemic stroke, we included results from the Stroke Onset Study (SOS).23 Both studies included individuals with either incident or recurrent events and both used the Onset Anger Scale with a cut-off of ≥5 to examine ischaemic stroke risk in the 2h following anger outbursts. Based on the meta-analysed data, there was a 3.62 (95% CI: 0.82–16.08; P = 0.09) times higher rate of ischaemic stroke in the 2h following an outburst of anger compared with other times. Since there was evidence of heterogeneity between the two studies (Q = 9.84, P = 0.002; I2 = 89.8%), a pooled estimate may not be appropriate. There was one study8 on outbursts of anger and the risk of ruptured intracranial aneurysms that reported a 6.30 (95% CI: 1.60–25.0) times higher rate of ruptured intracranial aneurysm in the hour following an outburst of anger.

Ventricular arrhythmia

There was one published study9 and one meeting abstract,10 reporting that anger episodes are a trigger of ventricular arrhythmia. Since the two studies used different designs, different anger measures and evaluated different hazard periods, the results could not be meta- analysed, but both reported statistically significant associations for a higher risk of ventricular arrhythmia immediately following outbursts of anger. In a study of 277 patients who had received implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) for standard indications (clinical or inducible ventricular arrhythmia),9 patients were asked to record their activities and emotions in the 15 min and 2h prior to any ICD shocks that they received using a 5-point Likert scale to rate the intensity of anger; they filled out a similar diary 1week later at the same time of day. One hundred and seven shocks were reported by 42 patients. Compared with other times, there was a 1.83 (95% CI: 1.04–3.16) times higher rate of ventricular arrhythmia in the 15 min after an anger outburst and a 1.35 (95% CI: 0.77–2.35) times higher rate in the following 15 min to 2 h. In the multicenter Triggers of Ventricular Arrhythmias prospective nested case-crossover study,10 1188 ICD patients were interviewed regarding their usual frequency of anger at entry into the study and at follow-up intervals; after each ICD discharge, participants were interviewed about episodes of anger in the hour prior to ICD discharge. Compared with other times, there was a 3.20 (95% CI: 1.80–5.70) times higher rate of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in the hour following moderate levels of anger and 16.7 (95% CI: 8.12–34.5) times higher in the hour after intense anger.

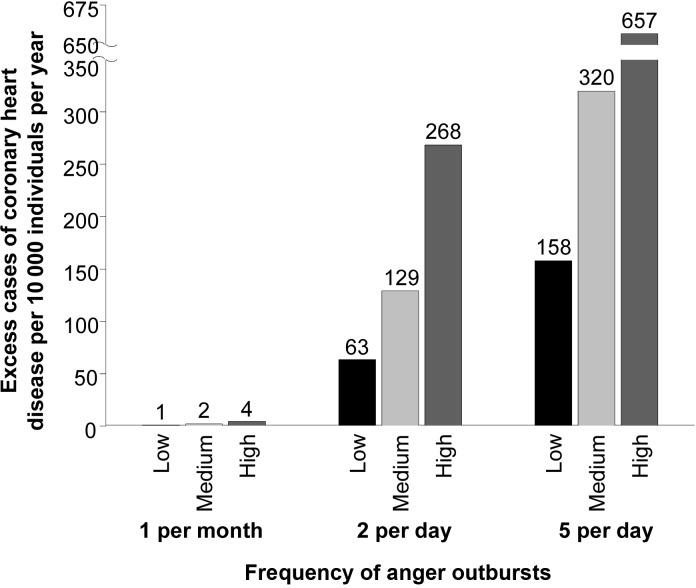

Absolute risk

Although the relative risk of a cardiovascular event following outbursts of anger is large and statistically significant, anger episodes may be rare and the heightened cardiovascular risk is transient so the impact on an individual's absolute risk of a cardiovascular event is small. However, the absolute risk is higher for individuals with a higher baseline cardiovascular risk and individuals who have frequent outbursts of anger (Figure 3). For instance, based on the combined estimate of a 4.74 times higher rate of MI or ACS in the 2h following outbursts of anger, the absolute impact of one episode of anger per month is only one excess cardiovascular event per 10 000 individuals per year at low (5%) 10-year cardiovascular risk and four excess cardiovascular events per 10 000 individuals per year at high (20%) 10-year cardiovascular risk. The absolute impact is higher for individuals with more frequent episodes of anger; five episodes of anger per day would result in ∼158 excess cardiovascular event per 10 000 per year for individuals at low (5%) 10-year cardiovascular risk and a similar frequency of anger outbursts would be associated with ∼657 excess cardiovascular events per 10 000 per year among individuals at high (20%) 10-year cardiovascular risk.

Figure 3.

Estimated number of excess cases of coronary heart disease per 10 000 individuals per year according to frequency of anger outbursts according to low (5%), medium (10%), or high (20%) 10-year risk of coronary heart disease.

Discussion

Based on the totality of the evidence, there is a higher risk of MI, ACS, ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, and arrhythmia in the 2h following outbursts of anger. It is possible that some of the between-study heterogeneity is due to regional differences in the type of anger expression and the interpretation of the questions. Although all but one9 of the studies used the Onset Anger Scale,2 they had different cut-offs to define exposure and different procedures for administering the scale. Therefore, in addition to differences in the baseline risk between the populations under study that may modify the risk from an event triggered by outbursts of anger, these study protocol differences may have contributed to the heterogeneity between studies of each outcome. Furthermore, although one may be tempted to infer that the heterogeneity in the magnitude of the association by the type of cardiovascular event is due to different biological mechanisms linking anger and the outcome of interest, it may also be at least partially due to these differences in study procedures.

Only three studies4,9,10 evaluated whether greater levels of anger intensity are associated with a greater level of cardiovascular risk, so we could not conduct a dose–response meta-analysis pooling estimates for different levels of anger intensity. However, both studies on ventricular arrhythmia9,10 reported stronger associations for being furious than for being moderately angry, and in another recent study,4 there was a greater MI risk for each increment in anger intensity.

Several studies evaluated whether the risk of a cardiovascular event triggered by anger outbursts may be mitigated by medical history, socioeconomic factors or regular medication use. However, sample sizes for stratifying on potential modifiers were small, so most of these differences were not statistically significant. Anger-associated events were more common among patients with lower levels of education, but it was not related to cardiovascular risk factors, having a previous MI, or the presence or absence of premonitory symptoms.13 Use of beta-blockers,2–4,6,7,24 aspirin,2,6 calcium antagonists,6,24 or nitrates24 may lower the risk from each outburst of anger. The studies on haemorrhagic stroke and arrhythmia did not evaluate whether medical history or behavioural and environmental factors modify the risk of an event triggered by outbursts of anger.

The impact of anger outbursts may be modified by trait anger. It is possible that an individual with an angry temperament is constantly at a relatively high level of physiological activation and is acclimated to the physiological response to anger. Therefore, he/she may experience a smaller spike in risk following each anger outburst than a person with a lower level of trait anger who is not used to the physiological response from outbursts of anger, though the absolute risk may be higher from accumulating more high-risk episodes over time. One study3 reported a lower risk of incident MI from each episode of anger among individuals with more frequent outbursts and individuals who tend to express their anger, but in one study,4 the association was not materially different by levels of trait anger. In addition to differences in risk, the frequency of outbursts is likely higher among people with an angry temperament. One study25 reported that patients who reported at least moderate anger in the 0–15 min before ICD shock reported higher levels of trait anger, hostility and aggressiveness, and lower levels of anger control, suggesting that those with higher trait anger have a higher frequency of anger outbursts that are intense enough to trigger an arrhythmia.

There are several potential mechanisms linking anger outbursts and cardiovascular events. Psychological stress has been shown to increase heart rate and blood pressure, and vascular resistance. This sympathetic activation is likely a common pathway for ischaemic and haemorrhagic events as well as cardiac arrhythmia. Haemodynamic changes may cause transient ischaemia and/or disruption of vulnerable plaques, especially among susceptible patients. Furthermore, it may stimulate an inflammatory and pro-thrombotic response, including increased platelet aggregation and plasma viscosity and decreased fibrinolytic potential. These changes may lead to an increased prevalence of plaques that are vulnerable to disruption and a higher probability of thrombotic occlusion, resulting in an ischaemic event.1,26,27

We have previously discussed the net impact of cardiovascular events triggered by outbursts of anger.1 The relative risks estimated in this meta-analysis indicate that there is a higher risk of cardiovascular events after outbursts of anger among individuals at risk of a cardiovascular event, but because each episode may be infrequent and the effect period is transient, the net absolute impact on disease burden is extremely low. However, with increasing frequency of anger episodes, these transient effects may accumulate, leading to a larger clinical impact. In addition, long-term risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as obesity and cigarette smoking and subclinical or established cardiovascular disease raise the baseline risk of acute cardiovascular events in any given hour. Therefore, assuming no differences in the relative risks, the absolute impact of anger outbursts will be higher among individuals with known risk factors.

Since residual confounding in the included studies and between-study heterogeneity is a concern in meta-analyses to summarize observational studies with different patient characteristics, the results should not be assumed to indicate the true causal effect of anger episodes on cardiovascular events.28 However, the results were fairly consistent across studies even though they were conducted >18 years in diverse populations, and the findings were robust to sensitivity analyses using different control periods. These studies used the case-crossover design29 to compare each individual's level of anger immediately prior to the cardiovascular event to anger levels at other times. Since each individual serves as his/her own comparator, the association between anger outbursts and cardiovascular disease is not confounded by stable health characteristics. Although the case-crossover design eliminates confounding by stable health characteristics, there can still be confounding by factors that change over time. However, some of the studies4 showed that the results were not materially altered after adjusting for potential confounding by co-exposures such as anxiety, physical activity, coffee consumption, and alcohol consumption. Premonitory symptoms may elicit feeling of anger and anxiety, resulting in reverse causation. However, in an analysis restricted to patients with no premonitory symptoms,3 the association was even stronger, and in one study4 the outcome was defined based on symptom onset rather than hospital admission time. Patients might have attempted to explain their cardiovascular event by overestimating anger episodes immediately before symptom onset and underestimating their exposure during the control period, resulting in recall bias and an overestimation of the association between outbursts of anger and cardiovascular risk. However, most of the studies ascertained information about anger episodes using structured interviews and the patients were not informed of the hypothesized duration of the hazard period. Since results that are not statistically significant are often difficult to publish, our systematic review may be subject to publication bias. However, we conducted a broad comprehensive search of several databases and reference lists of relevant articles, and we included unpublished data and meeting abstracts.

In conclusion, based on our review of nine case-crossover studies of individuals that experienced cardiovascular events, there is a higher risk of MI, ACS, ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, and arrhythmia in the 2h following outbursts of anger, with differences between the studies resulting in different magnitudes of the association. Since there is large heterogeneity between the studies, combined estimates of the IRR may not be meaningful. Yet, despite the differences between the studies, there was consistent evidence of a higher risk of cardiovascular events immediately following outbursts of anger.

Some medications may help sever the link between anger episodes and cardiovascular events by lowering the frequency of anger outbursts or by lowering the risk from each anger episode. In addition to the potential benefits of beta -blockers to break the link between anger outbursts and cardiovascular events, paroxetine and other serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors may reduce the frequency of anger outbursts and improve impulse control.30 Although it has not been rigorously evaluated in a randomized clinical trial, it is possible that psychosocial interventions may help lower the risk of cardiovascular events associated with outbursts of anger. Now that there is consistent evidence that anger outbursts are associated with a transiently higher risk of cardiovascular events, further research is needed to identify effective pharmacological and behavioural interventions to mitigate the risk of cardiovascular events triggered by outbursts of anger.

Funding

This work was supported by grants T32-HL098048 and F32-HL120505 from the NIH at the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest: no funding organization had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection; management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Mittleman MA, Mostofsky E. Physical, psychological and chemical triggers of acute cardiovascular events: preventive strategies. Circulation. 2011;124:346–354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Mulry RP, Tofler GH, Jacobs SC, Friedman R, Benson H, Muller JE. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction onset by episodes of anger. Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. Circulation. 1995;92:1720–1725. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Möller J, Hallqvist J, Diderichsen F, Theorell T, Reuterwall C, Ahlbom A. Do episodes of anger trigger myocardial infarction? A case-crossover analysis in the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP) Psychosom Med. 1999;61:842–849. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199911000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mostofsky E, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Relation of outbursts of anger and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strike PC, Perkins-Porras L, Whitehead DL, McEwan J, Steptoe A. Triggering of acute coronary syndromes by physical exertion and anger: clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. Heart. 2006;92:1035–1040. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.077362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipovetzky N, Hod H, Roth A, Kishon Y, Sclarovsky S, Green MS. Emotional events and anger at the workplace as triggers for a first event of the acute coronary syndrome: a case-crossover study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9:310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koton S, Tanne D, Bornstein NM, Green MS. Triggering risk factors for ischemic stroke: a case-crossover study. Neurology. 2004;63:2006–2010. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145842.25520.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vlak MH, Rinkel GJ, Greebe P, van der Bom JG, Algra A. Trigger factors and their attributable risk for rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a case-crossover study. Stroke. 2011;42:1878–1882. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lampert R, Joska T, Burg MM, Batsford WP, McPherson CA, Jain D. Emotional and physical precipitants of ventricular arrhythmia. Circulation. 2002;106:1800–1805. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031733.51374.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert C, Lampert R, Conti J, Chung M, Wang P, Muller J, Mittleman M. Abstract 3873: episodes of anger trigger ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Circulation. 2006;114(Suppl):831. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JQ, Ma N, Gao ZY, Wei YY, Chen F. Association between incidence of idiopathic ventricular tachycardia and risk factors with short-term effects: a case-crossover study. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2009;30:960–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Nachnani M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE, Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Nachnani M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE. Educational attainment, anger, and the risk of triggering myocardial infarction onset. The Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. Arch Int Med. 1997;157:769–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cochran W. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mostofsky E, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Tofler GH, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Risk of acute myocardial infarction after the death of a significant person in one's life: the Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study. Circulation. 2012;125:491–496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.061770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Robins JM. Control sampling strategies for case-crossover studies: an assessment of relative efficiency. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:91–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mostofsky E, Burger MR, Schlaug G, Mukamal KJ, Rosamond WD, Mittleman MA. Alcohol and acute ischemic stroke onset: the stroke onset study. Stroke. 2010;41:1845–1849. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.580092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Culic V, Eterovic D, Miric D, Rumboldt Z, Hozo I. Gender differences in triggering of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:753–756, A758. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00854-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burg MM, Lampert R, Joska T, Batsford W, Jain D. Psychological traits and emotion-triggering of ICD shock-terminated arrhythmias. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:898–902. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145822.15967.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH, Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1989;79:733–743. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steptoe A, Kivimaki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:360–370. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Schneider M, Davey Smith G. Spurious precision? Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 1998;316:140–144. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:144–153. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suls J. Anger and the heart: perspectives on cardiac risk, mechanisms and interventions. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]