Abstract

Alfred Werner described the attributes of the primary and secondary coordination spheres in his development of coordination chemistry. To examine the effects of the secondary coordination sphere on coordination chemistry, a series of tripodal ligands containing differing numbers of hydrogen bond (H-bond) donors were used to examine the effects of H-bonds on Fe(II), Mn(II)–acetato, and Mn(III)–OH complexes. The ligands containing varying numbers of urea and amidate donors allowed for systematic changes in the secondary coordination spheres of the complexes. Two of the Fe(II) complexes that were isolated as their Bu4N+ salts formed dimers in the solid-state as determined by X-ray diffraction methods, which correlates with the number of H-bonds present in the complexes (i.e., dimerization is favored as the number of H-bond donors increases). Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies suggested that the dimeric structures persist in acetonitrile. The Mn(II) complexes were all isolated as their acetato adducts. Furthermore, the synthesis of a rare Mn(III)–OH complex via dioxygen activation was achieved that contains a single intramolecular H-bond; its physical properties are discussed within the context of other Mn(III)–OH complexes.

Keywords: Secondary coordination sphere, Hydrogen bonds

1. Introduction

Alfred Werner described the primary and secondary coordination spheres in his development of modern inorganic chemistry for which he was awarded the 1913 Nobel prize in chemistry [1]. The primary coordination sphere is concerned with metal–ligand interactions which often govern molecular/electronic structure and reactivity. In the context of coordination chemistry, the secondary coordination sphere includes the microenvironment around a metal center and does not interact with metal centers through covalent bonds. Rather, the secondary coordination sphere is defined as interactions with ligands or other species within close proximity to the metal ion. The integration of these types of interactions within one molecular species is necessary to fully garner the capabilities of transition metal ions and provides many design challenges to modern inorganic chemists. In particular, the ability to control the secondary coordination sphere with non-covalent interactions has hindered progress in transition metal chemistry.

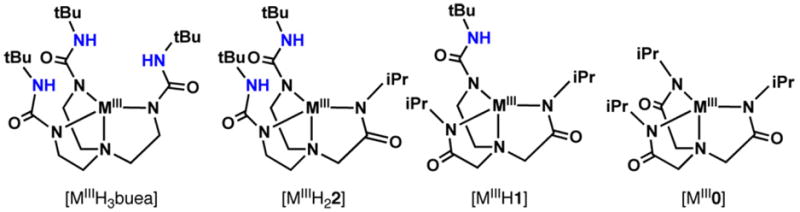

Several groups have been developing approaches whose aim it is to regulate both the primary and the secondary coordination sphere in synthetic transition metal complexes and proteins [2]. Our strategy involves the synthesis of complexes with intramolecular hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) [3]. The design of our ligands has been influenced by the structures found within the active sites of metal-loproteins that use H-bonds proximal to metal ions to control many aspects of biological coordination chemistry [4]. These aspects range from physical properties such as redox potentials to substrate specificity and activation of small molecules. We have developed a series of tripodal ligands that allows for the systematic variation in of the number of intramolecular H-bond donors while keeping the primary coordination sphere constant (Fig. 1) [5]. These trianionic ligands utilize amidate/ureate groups that promote trigonal bipyramidal coordination geometry and provide H-bonding networks that can contain up to three intramolecular H-bonds. Previous studies have demonstrated how H-bonds affect the activation of dioxygen in cobalt(II) complexes and the physical properties in a series of Fe(III)-OH complexes [5]. In this report we examine the chemistry associated with a series of M(II) (M = Mn, Fe) complexes and present evidence that H-bonds can affect solution speciation. We further present the preparation and molecular structure of a new Mn(III)–OH complex and compare its structural properties to related complexes using this series of ligands.

Fig. 1.

The series of metal complexes with varying number of intramolecular H-bond donors used in this study.

2. Experimental details

2.1. General methods

All chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used as received unless otherwise noted. Potassium hydride, dispersed in mineral oil, was filtered and washed at least five times with pentane and Et2O, dried on a vacuum line, and stored under an argon atmosphere. Ferrocenium tetrafluoroborate was synthesized as described by Geiger [6]. Solvents were purified using a JC Meyer Co. solvent purification system. All metal complexes were prepared in a Vacuum Atmospheres Co. dry box with an argon atmosphere. The ligands were prepared according to literature methods [5]. The K2[MnIIH3buea(κ1-OAc)] salt was prepared as described by literature methods [7].

[K(18-crown-6)]2[Mn(II)H1(OAc)]

H41 (100 mg, 0.28 mmol) was treated with KH (34 mg, 0.85 mmol) in 3 mL of DMA and allowed to stir until gas evolution ceased (~1 h). The foamy reaction mixture was treated with Mn(OAc)2 (48 mg, 0.28 mmol) and allowed to stir for 2 h during which potassium acetate precipitated and was removed by filtration with a medium porosity glass fritted funnel. The filtrate was treated with 18-crown-6 (150 mg, 0.57 mmol) and stirred until completely dissolved. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the resulting white residue was treated with Et2O until a white precipitate persisted, which was then collected on a glass fritted funnel and dried for 1 h under vacuum to yield a free flowing white powder (232 mg, 71%). FTIR (Nujol, cm−1) ν(NH) 3373, 3170; ν(CO) 1641, 1552. Anal. Calc. for [K(18-crown-6)]2[MnIIH1(OAc)]·DMA, C47H92K2MnN6O18: C, 48.31; H, 8.09; N, 7.59. Found: C, 48.56; H, 7.98; N, 7.23%. X-band EPR (DMSO, 77 K) g = 23.45, 4.39, 3.12, 2.46, 1.96.

[K(18-crown-6)]2[MnIIH22(OAc)]

The same procedure for preparation of [[K(18-crown-6)]2[MnIIH1(OAc)] was followed using H52 (100 mg, 0.25 mmol), KH (30 mg, 0.75 mmol), Mn(OAc)2 (43 mg, 0.25 mmol), and 18-crown-6 (13 mg, 0.50 mmol) to afford 280 mg (44%) of the desired salt. ESIMS (m/z): 452.2 [MnIIH22]−; 512.3 [MnIIH22(OAc)]−. Anal. Calc. for [K(18-crown-6)]2 [MnIIH22 (OAc)]·DMA, C49H97K2MnN7O18: C, 48.88; H, 8.33; N, 8.10. Found: C, 48.82; H, 8.11; N, 8.13%. X-band EPR (DMA, 77 K) 28.45, 5.90, 3.06, 2.48, 1.96.

[K(18-crown-6)]2[Mn(II)0cyp(OAc)]

The same procedure for preparation of [K(18-crown-6)]2[MnIIH1iPr(OAc)] was followed using H30cyp (100 mg, 0.26 mmol), KH (31 mg, 0.77 mmol), Mn(OAc)2 (44 mg, 0.26 mmol), and 18-crown-6 (140 mg, 0.53 mmol) to yield 220 mg (73%) of the desired salt. FTIR (Nujol, cm−1) ν(NH) 3165; ν(CO) 1646, 1554. Anal. Calc. for [K(18-crown-6)]2[MnII0cyp (OAc)]·DMA, C51H93K2MnN5O18: C, 51.47; H, 8.01; N, 5.65. Found: C, 51.15; H, 7.83; N, 5.85%. X-band EPR (DMSO, 77 K) g = 15.59, 5.61, 3.88, 2.87, 2.33, 1.91.

[K(18-crown-6)]2[Mn(II)0ipr(OAc)]

The same procedure for preparation [K(18-crown-6)]2[MnIIH1(OAc)] was followed using H30ipr (100 mg, 0.32 mmol), KH (38 mg, 0.96 mmol), Mn(OAc)2 (55 mg, 0.32 mmol), and 18-crown-6 (170 mg, 0.64 mmol) to produce 220 mg (68%) of the desired salt. FTIR (Nujol, cm−1) ν(NH) 3168; ν(CO) 1647, 1553. Anal. Calc. for [K(18-crown-6)]2[MnII0ipr(OAc)], C41H78K2MnK2N4O17: C, 47.76; H, 7.89; N, 5.62. Found: C, 47.71; H, 7.62; N, 5.43%. X-band EPR (DMA, 77 K) g = 16.18, 5.98, 3.94, 2.95, 2.44, 2.97.

[Bu4N]2[Fe(II)H3buea]2

A solution of H6buea (200 mg, 0.45 mmol) dissolved in 4 mL of anhydrous DMA was treated with solid KH (55 mg, 1.36 mmol) and stirred until gas evolution ceased. Fe(OAc)2 (79 mg, 0.45 mmol) was added to the pale yellow solution, and stirring was continued for 30 min. The resulting amber filtrate was treated with [Bu4N][OAc] (140 mg, 0.45 mmol) and stirred for 2 h, resulting in the precipitation of a white solid (305 mg) that was filtered, washed twice with Et2O, and dried under vacuum. The white solid was stirred in CH3CN for 1 h and filtered to remove KOAc (105 mg, 96%). The light yellow filtrate was concentrated to half its original volume and the slow addition of Et2O resulted in the formation of a white solid, which was then filtered, washed with Et2O, and dried under vacuum to afford 150 mg (47%) of the desired salt. Anal. Calc. for [Bu4N]2[FeIIH3−buea]2, C74H156Fe2N16O6: C, 60.14; H, 10.64; N, 15.16. Found: C, 61.19; H, 10.89; N, 15.68%. FTIR (Nujol, cm−1) ν(NH) 3335, ν(CO) 1663, 1592, 1571, 1556. Single crystals were grown by diffusion of Et2O into a CH3CN solution of the crude complex.

[Bu4N]2[Fe(II)H22iPr]2 was prepared following a similar procedure to that of [Bu4N]2[Fe(II)H3buea]2 with H52iPr (150 mg, 0.37 mmol), KH (45 mg, 1.12 mmol), Fe(OAc)2 (66 mg, 0.37 mmol), and [Bu4N][OAc] (113 mg, 0.37 mmol). The amount of KOAc obtained was 105 mg (96% for 3 equiv) and 100 mg (42%) of [Bu4N]2 [FeIIH22iPr] was isolated. Single crystals were grown by diffusion of Et2O into a CH3CN solution of the complex. FTIR (Nujol, cm−1) ν(NH) 3332, ν(CO) 1661, 1590, 1561, 1520. Repeated attempts to obtain a satisfactory elemental analysis were unsuccessful.

K2[Mn(II)H1(OH)]

H41 (0.050 mg, 0.14 mmol) was deprotonated with 4 equiv KH (23 mg, 0.57 mmol) in 3 mL of DMA and allowed to stir for 4 h. To the thick foamy suspension was added Mn(OAc)2 (26 mg, 0.15 mmol) after which the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min. H2O (2.5 μL, 0.14 mmol) was added and allowed to stir for 30 min. The mixture was filtered and the resulting DMA solution was allowed for slow vapor diffusion of Et2O yielding a white microcrystalline solid, which after several days was isolated on a fritted glass funnel and washed 3 × 3 mL MeCN, 3 × 5 mL Et2O (32 mg, 46%). FTIR (Nujol, cm−1) ν(OH) 3503; ν(NH) 3244, 3142; ν(CO) 1655, 1567, 1507. Anal. Calc. for K2[MnIIH1(OH)]·0.5DMA, C19H37.5K2MnN5.5O4.5: C, 41.93; H, 7.37; N, 13.65. Found: C, 41.63; H, 6.89; N, 14.05%. X-band EPR (DMF, 77 K) g = 14.32, 5.81, 1.99, 1.55, 1.28.

K[Mn(III)H1(OH)]

Method A. H41 (110 mg, 0.30 mmol) was dissolved in 3 mL of DMA and treated with KH (36 mg, 0.90 mmol) and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir. After ~19 h the reaction mixture was treated with Mn(OAc)2 (51 mg, 0.29 mmol) and stirred for an addition 1 h, after which the reaction was filtered to remove 1 equiv of KOAc (26 mg, 91%). The pale yellow filtrate was treated with O2 (7.2 mL, 0.29 mmol, 298 K, 1 atm) causing an immediate color change to dark forest green, which slowly turned brownish green. After stirring for an additional 1 h the system was evacuated to remove excess O2 and brought back into an anaerobic drybox. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was extracted with MeCN (1 mL) and DMA (1 mL) and passed through a fritted glass funnel to remove a second equiv of KOAc. The green filtrate was concentrated to less than 1 mL and Et2O was added to precipitate the salt, which was collected on a fritted glass funnel. A brown species was removed from the crude green solid by washing up to 3 × 0.5 mL DMA (or until washings did not have a brown color) leaving behind a teal green solid. The teal green solid was washed with Et2O and dried under reduced pressure for 1 h (23 mg, 16% yield). X-ray quality crystals were obtained by dissolving the teal green solid in ~2 mL of DMA and diffusing Et2O. FTIR (Nujol, cm−1) ν(OH) 3645; ν(NH) 3278, 3175; ν(CO) 1634, 1596, 1582, 1533. UV–Vis λmax (DMA or DMSO, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)) 420 nm (450), 675 nm (590). Anal. Calc. for K[MnIII-H1(OH)], C17H33KMnN5O4: C, 43.86; H, 7.15; N, 15.04. Found: C, 43.58; H, 7.24; N, 14.29%. Method B. K2[MnIIH1(OH)] (50 mg, 0.10 mmol) was dissolved in 6 mL of DMA to afford a 17 mM soluton. A 5 mL portion of the stock solution (0.083 mmol) was treated with solid [FeCp2]BF4 (19 mg, 0.070 mmol) causing the immediate color change from colorless to forest green whose spectroscopic features matched those of K[MnIIIH1(OH)] prepared from O2.

2.2. Physical methods

FTIR spectral data were collected using a Varian 800 FTIR Scimitar Series spectrometer. Absorption spectra were collected using a Cary 50 Scan UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Parallel-mode X-band electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were collected using a Bruker EMX spectrometer equipped with an ER041XG microwave bridge, an ER4116DM dual-mode cavity, and an Oxford Instrument liquid He quartz cryostat. All EPR spectra were recorded at 10 K and unless otherwise stated EPR experiments were conducted using the following instrument parameters:modulation amplitude 9.02 G; power 0.64 mW. Electrospray mass spectra were collected using a Waters Micromass LCT Premier Mass Spectrometer.

2.3. Crystallography

Crystals were attached to a glass fiber and mounted under nitrogen on a Bruker SMART APEX CCD Single Crystal Diffraction System. Full hemisphere of diffracted intensities were measured for a single domain specimen using graphite-monochromated MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). X-rays were provided by a fine-focus sealed X-ray tube operated at 50 kV and 30 mA. The structures were solved using direct methods and all stages of the weighted full-matrix least-square refinements were conducted using data. Crystal data and refinement information for crystal structures can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for the iron and manganese complexes.

| Formula | {(Bu4N)2[FeIIH3buea]2}·4MeCN C82H168Fe2N20O6 | {(Bu4N)2[FeIIH22]2}·MeCN C74H152Fe2N16O6 | K[MnIIIH1(OH)]·1.5DMA C23H46.5KMnN6.5O5.5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formula weight | 1642.06 | 1473.82 | 596.21 |

| T (K) | 100(2) | 100(2) | 100(2) |

| Crystal system | triclinic | triclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | P1̄ | P1̄ | C2/c |

| a (Å) | 12.9193(9) | 11.9559(10) | 25.218(5) |

| b (Å) | 14.3082(10) | 13.2362(11) | 9.854(2) |

| c (Å) | 14.6513(10) | 14.5757(12) | 26.226(6) |

| α (°) | 89.7650(10) | 105.902(2) | 90.00 |

| β (°) | 71.6280(10) | 96.099(2) | 107.247(5) |

| γ (°) | 71.03600(10) | 103.706(2) | 90 |

| Z | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| V (Å3) | 2416.14 | 2118.7 | 6224 |

| DCalc (g/cm3) | 1.129 | 1.155 | 1.273 |

| Independent reflections | 14579 | 12777 | 6108 |

| R1 | 0.0575 | 0.0751 | 0.0360 |

| wR2 | 0.1759 | 0.1741 | 0.0971 |

| Goodness-of-fit (GOF) on F2 | 1.061 | 1.064 | 1.012 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis of the M(II) complexes

Preparation of the MnII complexes was accomplished by deprotonation of the appropriate tripodal precursor with 3 equiv of KH in DMA to obtain the tri-anionic ligand, which was subsequently treated with Mn(II)(OAc)2. Purification of these Mn(II) complexes was facilitated by the precipitation of 1 equiv of KOAc (>90%) because this salt has limited solubility in DMA. The nearly quantitative isolation of only 1 equiv of KOAc suggested that the other equivalent of acetate is coordinated to the Mn(II) centers in each complex, as we have previously observed in [Mn(II)H3buea(κ1-OAc)]2− [7]. The coordination mode is still unknown, but we propose that the acetate would also bind in a similar monodentate manner. We found that the Mn(II) complexes could be more readily purified as either their Me4N+ or [(K ⊂ 18-crown-6)]+ salts. Repeated attempts to grow single crystals of each salt that were suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were unsuccessful. However, elemental and mass spectral data support the premise that one acetate remains bound to the manganese ion.1

The Mn(II) complexes of these ligands have different coordination properties with acetate than their Co(II) and Fe(II) analogs. Treating either [H3buea]3−, [H22]3−, [H1]3−, and [0]3− with Co(OAc)2 or Fe(OAc)2 under the same experimental conditions produced the corresponding metal complexes and 2 equiv of KOAc [5]. Furthermore, spectroscopic and analytical properties of these Co(II) and Fe(II) complexes gave no indication that acetate was coordinated to the metal centers. For example, we have reported the molecular structures of [M(II)0ipr]− (M(II) = Co and Fe), [Co(II)H1iPr]−, and [CoH22iPr]− and found that all have similar trigonal monopyramidal coordination geometry [5a,8]. The reason(s) for this difference in acetate binding is still unknown.

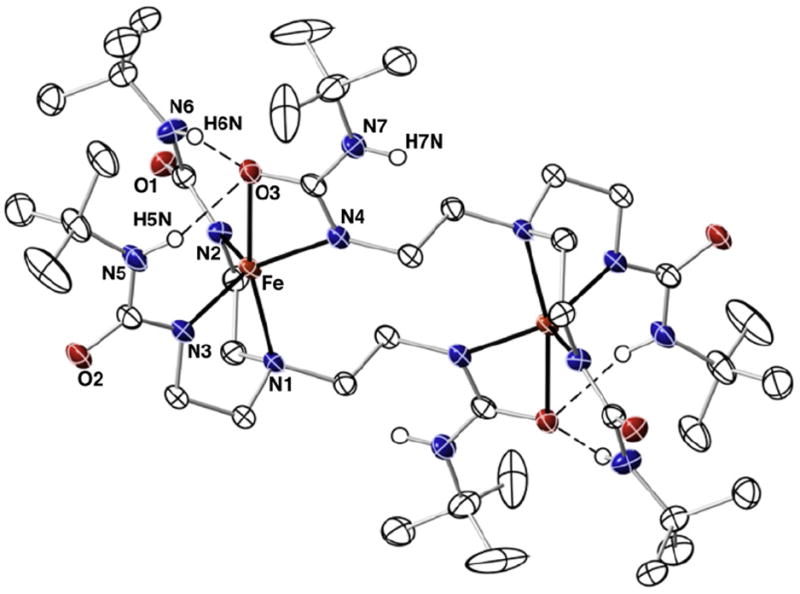

In the course of our studies we found that changing the counterions of [Fe(II)H3buea]− and [Fe(II)H22]− from potassium to Bu4N+ produced salts that were soluble in a range of solvents, including acetonitrile that allowed for the growth of single crystals. Moreover, the Bu4N+ salt had different EPR and FTIR properties from its potassium analog, suggesting the possibility that a change in structure may have occurred. Our solid state structural studies support this premise, in that this salt crystallized with the [Fe(II)H3buea]22− dimer (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Thermal ellipsoid diagram for the molecular structure of [Fe(II)H3buea]22−. Only the urea hydrogen atoms are shown for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

3.2. Solid-state structures of [Fe(II)H3buea]22− and [Fe(II)H22]22−

The solid-state structures of [Bu4N]2[Fe(II)H3buea]2 and [Bu4-N]2[Fe(II)H22]2 were examined using X-ray diffraction methods and views of the anions are shown in Figs. 2 and 4. Selected bond length and angles can be found in Table 2. The overall lattice structures contained disordered solvent molecules that we were not able to model. However, the anions in the structures of both salts are of high enough quality for us to comment on the primary and secondary spheres about the iron centers. In [Fe(II)H3buea]22− each iron center has an N4O primary coordination sphere that are related by a center of symmetry. There are no other exogenous ligands bonded to the iron center with the [H3buea]3− ligands providing all the donor atoms. Each [H3buea]3− ligand coordinates as a tridentate ligand to one iron centers, binding through the apical N1 atom and the deprotonated ureate nitrogen atoms N2 and N3. The Fe–N1 bond length of 2.270(1) Å and the Fe–N2 and Fe–N3 bond distances of 2.034 (1) and 2.030 (1) Å are similar to what we have observed with other Fe(II) complexes having ureate/amine donors [5b,8,9]. A striking feature of this complex is that the tripodal arm containing N4 does not interact with the same iron center as N1, N2, and N3. Rather, this remaining arm is splayed toward the second iron center, to which it coordinates through both N4 and O3 of the urea group. The Fe–N4 bond length of 2.041(1) Å is statistically different from the other Fe–Nurea bond distances and the Fe–O3 bond distance of 2.388(1) Å is significantly longer. The N2–Fe–N4 and N3–Fe–N4 bond angles are ~122°, whereas N2–Fe–N3 bond angle is significantly shorter at 115.08(6)°. In addition, the O3–Fe–N1 bond angle is only 166.70(5)°. Taken together, these metrical results suggest the overall primary coordination sphere is best described as distorted trigonal bipyramidal and is supported by an index of trigonality parameter (τ) of 0.74 [10].

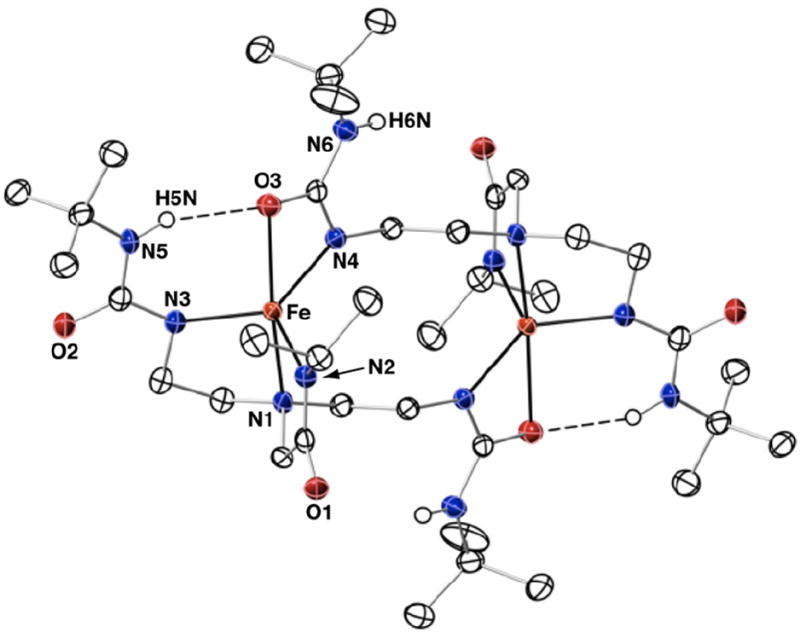

Fig. 4.

Thermal ellipsoid diagram for the molecular structure of [Fe(II)H22]22−. Only the urea hydrogen atoms are shown for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Table 2.

Selected metrical data for [FeIIH3buea]22− and [FeIIH22]22−.

| [Fe(II)H3buea]22− [Fe(II)H22]22− | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bond distances (Å) | ||

| Fe–O3 | 2.388(1) | 2.335(2) |

| Fe–N1 | 2.570(1) | 2.231(2) |

| Fe–N2 | 2.034(1) | 2.042(2) |

| Fe–N3 | 2.030(1) | 2.025(2) |

| Fe–N4 | 2.041(1) | 2.060(2) |

| Fe⋯Fe | 6.119 | 5.950 |

| τ | 0.74 | 0.71 |

| Bond angles (°) | ||

| N1–Fe–O3 | 166.70(5) | 168.96(7) |

| N3–Fe–N4 | 122.41(6) | 126.60(9) |

| N4–Fe–N2 | 122.34(5) | 118.77(9) |

| N2–Fe–N3 | 115.08(6) | 114.46(9) |

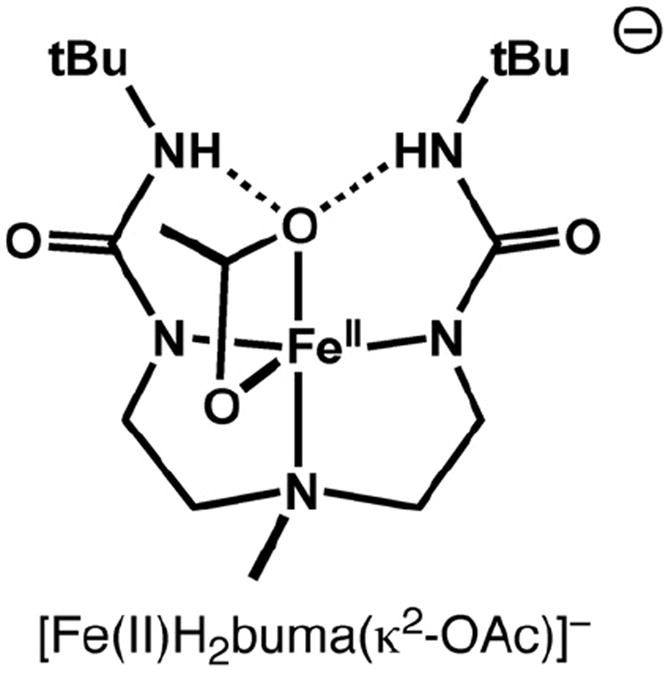

The secondary coordination sphere is dominated by a H-bond network between O3 of the extended urea and the NH groups containing N5 and N6. Two intramolecular H-bonds are formed with N5⋯O3 and N6⋯O3 distances of 3.148 and 3.012 Å. These distances are slightly longer that what is normally observed with other ligands within this type of H-bonding cavity. However, the relatively longer Fe–O3 bond length is undoubtedly caused, in part, to the H-bonds surrounding the urea group. This unsymmetrical coordination of the urea is similar to what we have observed with other bidentate anions to iron, such as acetate. In fact, the coordination spheres in [Fe(II)H3buea]22− are analogous to the Fe(II)-acetato complex with the tridentate ligand bis[(N′-tert-butylureido)-N-ethyl]-N-methylamine ([H2buma]2−, Fig. 3) [11]. Note that in [Fe(II) H2buma(κ2-OAc)]2− the acetate coordinates in a unsymmetrical manner and only one of its oxygen atoms is involved in H-bonding.

Fig. 3.

Representation of the structure for [Fe(II)H2buma(κ2-OAc)]−.

The molecular structure of [FeIIH22]22− possessed many aspects that were found in [Fe(II)H3buea]2− (Fig. 4). The [H22]3− ligand also spans two metal centers, with one urea arm binding in a bidentate mode to a second iron. The iron centers have N4O primary coordination spheres with distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometries (τ = 0.71). The main difference between the two structures is in their secondary coordination sphere because [H22]3− only provided a single H-bond donor. Thus each bidentate urea group has an N5–H5⋯O3 interaction with an N5⋯O separation of 2.903 Å. The presence of only one H-bond also results in a slight, but statistically significant, shortening of the Fe–O3 bond length to 2.335(2) Å. In addition, the Fe⋯Fe separation is shortened to 5.950(2) Å in [FeH22]22− from 6.119(1) Å in [Fe(II)H3buea]22−.

We have obtained several molecular structures of metal complexes with [H3buea]3− and all were monomeric species with the three arms of the tripod coordinated to the same metal ion.

The molecular structure of [Fe(II)H3buea]22− represents a new binding mode in which one arm from [H3buea]3− coordinated to another species (in this case, a second [Fe(II)H3buea]− complex). Our earlier systems are different in that they had an exogenous ligand within cavity that was able to form H-bonds [9,12]. We have shown that the urea cavity formed by [H3buea]3− has a strong propensity to form H-bonds, which we have used to prepare a variety of monomeric, five-coordinate hydroxo and oxo complexes. In the absence of an exogenous fifth ligand, it appears that the complex is capable of reorganizing to adopt a trigonal bipyramidal coordination that places a ligand (e.g., a mono-deprotonated urea group) that binds to the iron center and forms H-bonds. Another difference is the use of Bu4N+ as the counterion instead of potassium ions as we have done in the past. It is not known how the change in counterion effects this type of chemistry—we have never been able to structurally characterized a potassium salt for a complex with [H3buea]3− that does not have an exogenous ligand presence within the H-bonding cavity.

The structure of [Fe(II)H22]22− showed that this ligand can also form dimeric complexes in the absence of an exogenous ligand. However, we are unsure whether this type of coordination chemistry can be extended to other metal ions. As mentioned above, structural studies on K[CoH22] revealed that all three arms of the tripod are coordinated to the same Co(II) center [5a]. In addition, we have structurally characterized K[Fe(II)0] and K[Co(II)0], and found that both complexes are monomeric with a trigonal monopyramidal coordination geometry [5a,8].

3.3. EPR studies on the Fe(II) complex

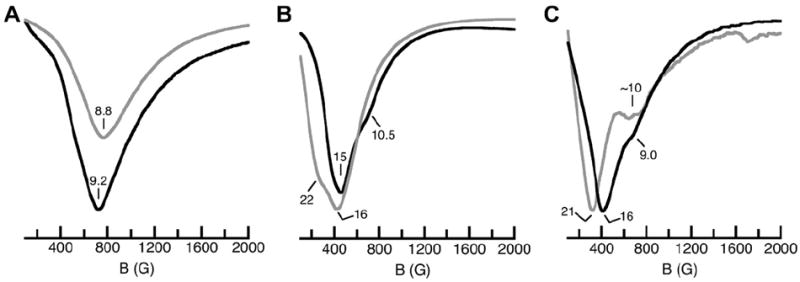

We have investigated the solution speciation of these Fe(II) complexes using EPR spectroscopy. All the complexes are high spin with S = 2 spin ground states. Conventional perpendicular-mode X-band EPR spectroscopy was not helpful in this study because integer spin systems are typically not detectable. We have thus turned to parallel-mode (∥-mode) methods, which can be used to observe transitions from species within an S = 2 spin manifold. For the present study, we are using this method to qualitatively investigate these types of Fe(II) complexes.

The low temperature (4 K) ∥-mode EPR spectrum for a frozen DMA solution of K[Fe(II)0] displayed a relative broad feature at a g-value of 9.2 (Fig. 5). Signals with similar g-values have been reported for other monomeric high-spin Fe(II) complexes [12b]. A slightly broader spectrum at g = 8.8 was obtained for a solid sample of this salt, suggesting that the electronic and molecular structures of the Fe(II) species in the solid-state and solution are similar. Because we have determined that [Fe(II)0]− is a monomer in the solid state, we propose that the complex remains monomeric in solution. In our own studies, we have used this signal as a reference for monomeric Fe(II) species to help probe the speciation of the other complexes in solution.

Fig. 5.

∥-mode EPR spectra for [Fe(II)0]− (A), [Fe(II)H3buea]22− (B), and [Fe(II)H22]2− (C) measured at 4 K. Gray spectra are from solid-state samples and black spectra are from frozen acetonitrile solutions.

The ∥-mode EPR spectra for solid samples of [Bu4N]2[Fe(II)H3buea]2 had a broad feature at g = 16 and a shoulder centered at g = 22 (Fig. 6A), features that are assigned to the dimeric complexes identified by X-ray diffraction methods. Frozen CH3CN solution of [Bu4N]2[Fe(II)H3buea]2 gave ∥-mode EPR spectra that had a similar broad peak centered at g = 15. There is also a small shoulder at g = 11 that could be caused by a small amount of monomeric Fe(II) complex being present (i.e., [Fe(II)H3buea]−). Nevertheless, the similarities between the solid-state and frozen solution spectra indicate that the dimeric [Fe(II)H3buea]22− complex remains the predominate Fe(II) species in acetonitrile. [Fe(II)H22]22− also appears to remain a dimer in solution as the ∥-mode EPR spectrum for a frozen acetonitrile solution of [Bu4N]2[Fe(II)H22]2 also has a peak at g = 16 and shoulder at g = 9.0 (Fig. 6B). Notice that the solid-state spectrum is comparable with features at g-values of 21 and ~10.

Fig. 6.

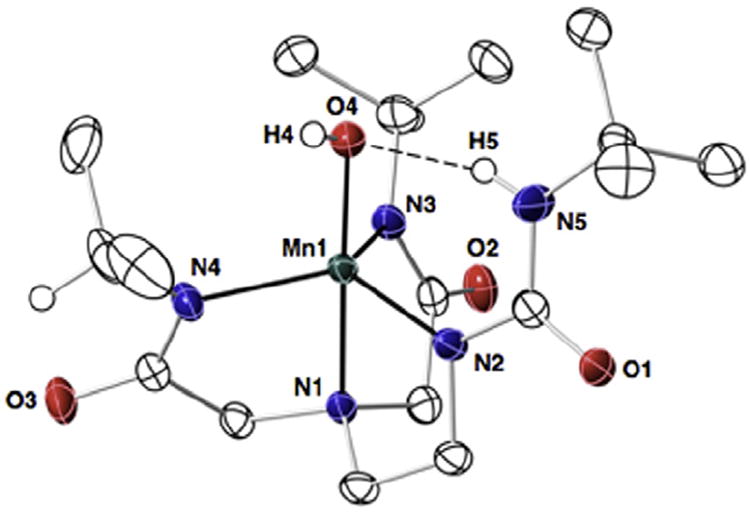

Thermal ellipsoid diagram for the molecular structure of [Mn(III)H1(OH)]−. Only the urea, hydroxo, and methine hydrogen atoms are shown for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

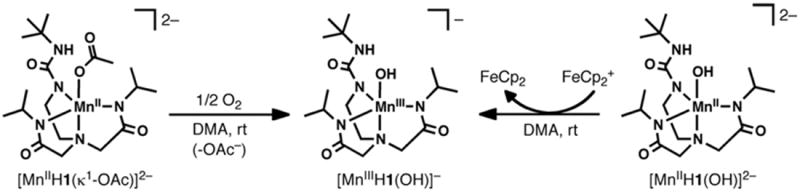

3.4. Preparation of [Mn(III)H1(OH)]−

We have previously reported the preparation and structural characterization of K[Mn(III)H3buea(OH)] and K[Mn(III)0(OH)] and found that the anions of each salt were monomeric with trigonal bipyramidal coordination geometry [7,12b,13]. The related Mn(III)–OH complex with [H1]3− has now been prepared, using a procedure in which K2[MnIIH1(OAc)] was oxidized with dioxygen (Scheme 1).2 FTIR spectroscopy was used to analyze the energies of the O–H vibrations in the Mn(III)–OH complex. The O–H vibration for [Mn(III)H1(OH)]− was found at ν(O–H) = 3644 cm−1, which is the same within experimental error to the value reported for [Mn(III)0(OH)]− (ν(O–H) = 3643 cm−1). The similarities in these energies suggest that one intramolecular H-bond to the hydroxo ligand does not have a significant effect on the energy of this vibration. However, both these values are significantly larger than the ν(O–H) = 3614 cm−1 found for [MnIIIH3buea(OH)]−, a complex that has three intramolecular H-bonds to the hydroxo ligand. We have also reported vibrational data on the analogous series of Fe(III)–OH complexes and a similar trend was observed, although with a larger spread in values ([Fe(III)H3buea(OH)]− (ν(O–H) = 3632 cm−1), [Fe(III)H1(OH)]− (ν(O–H) = 3676 cm−1), and [Fe (III)0(OH)]− (ν(O–H) = 3690 cm−1)) [5b].

Scheme 1.

Preparative routes to [Mn(III)H1(OH)]−.

3.5. Molecular structure of K[Mn(III)H1(OH)]

Crystals suitable for diffraction were obtained for K[Mn(III)-H1(OH)] and its structure was solved using X-ray diffraction methods (Fig. 6). Selected bond distances and angles are listed in Table 3. The manganese center has trigonal bipyramidal coordination geometry (τ = 0.94)3 with the trigonal plane being defined by the deprotonated nitrogen atoms N2, N3, and N4. The average N–Mn1–N angle within the trigonal plane is 117.1(3)°, which agrees with the average bond angles of 117.3(1)° and 118.2(1)° found for K[Mn(III)0(OH)]− and K[Mn(III)H3buea(OH)]−. The axial coordination sites in [Mn(III)H1(OH)]− are occupied by the apical nitrogen N1 and hydroxo oxygen O4 with an N1–Mn1–O4 bond angle of 177.41(6)°. This bond angle is also similar to those reported for [MnIII0(OH)]− (177.7(2)°) and [MnIIIH3buea(OH)]− (177.13(8)°).

Table 3.

Selected bond distances and angles for [Mn(III)H1(OH)]−.

| [Mn(III)H1(OH)]− | |

|---|---|

| Distances (Å) | |

| Mn–O4 | 1.846(1) |

| Mn–N1 | 2.028(2) |

| Avg. Mn–Neq | 2.048(2) |

| N5⋯O4 | 2.804(2) |

| Angles (°) | |

| N1–Mn–O4 | 177.41(6) |

| N2–Mn–N3 | 116.92(6) |

| N3–Mn–N4 | 113.84(6) |

| N4–Mn–N2 | 121.24(7) |

| Avg. N–Mn–N | 117.3(1) |

| τ | 0.94 |

The complex [Mn(III)H1(OH)]− contains one intramolecular H-bond between O4 and N5–H5 of the [H1]3− ligand, as indicated by the O4⋯N5 distance of 2.804(3) Å. The isopropyl moieties are arranged such that their methyl groups are positioned inward toward the manganese center and thus complete the cavity structure around the Mn–OH unit. Note that both methine C–H groups are directed away from the metal center and have adopted a syn conformation with the amide carbonyl groups. A Mn1–O4 bond length of 1.846(1) Å was observed in the [Mn(III)H1(OH)]−, which is significantly shorter than the 1.872(2) Å distance found for the nalogous bond in [Mn(III)H3buea(OH)]−. Furthermore, [Mn(III)0(OH)]− which has no intramolecular H-bonds has the shortest Mn–O(H) bond length of 1.816(4) Å. This difference in Mn–O(H) bond lengths correlates with the number of intramolecular H-bonds present in the complexes.

4. Conclusion

We presented results on the properties of Mn(II) and Fe(II) complexes of a series of tripodal ligands containing a varied number of H-bond donors. Our studies on the Mn(II) complexes demonstrated each complex is five-coordinate, with a coordinated acetate ion. The previously characterized structure of [Mn(II)H3buea(κ1-OAc)]2− revealed that an acetate ion is bonded within the H-bonding cavity formed by the urea groups of [H3buea]3−. This is in contrast to the chemistry observed with Fe(II) complexes of these ligands, in which no acetate ligand is present. It is unknown why the manganese complexes bind acetate while their Fe(II) analogs do not [14]. However, the presence of the acetato ligand appears to reinforce the cavity structure so that all arms of the tripod bind to a single metal ion. In the absence of an exogenous ligand, as was observed in the iron complexes, two of the complexes with urea groups formed dimers. One of the urea arms of [H3buea]3− and [H22]3− binds in a bidentate manner to a second Fe(II) center providing the necessary requirements to both primary and secondary coordination spheres. We also suggest that the dimeric structures of [Fe(II)H3buea]22− and [Fe(II)H22]22− are maintained in MeCN solution, a premise supported by comparison of their ∥-mode EPR spectra in both solid and solution states to those of the monomeric K[Fe(II)0] salt. Finally, our investigations on [Mn(III)H1(OH)]− further illustrates the effects of intramolecular H-bonds on the structural and physical properties of metal complexes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health, USA (GM050781) and National Science Foundation, USA (0738252) for financial support.

This work is dedicated to Alfred Werner on the 100th Anniversary of his Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1913.

Footnotes

See experimental conditions for EA and mass spectral results.

[Mn(III)H1(OH)]− could also be prepared by oxidation of [Mn(II)H1(OH)]2− with [FeCp2]BF4. Attempts to prepare the analogous Mn(III)OH complex using the ligand [H22]3− following similar procedures were unsuccessful.

For comparison, the τ values for K[Mn(III)0(OH)]− and K[Mn(III)H3buea(OH)]− are 0.87 and 0.71, respectively [12b,13].

Appendix A. Supplementary data

CCDC 883303, 883304, and 883305 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for K[MnIIIH1(OH)]·1.5DMA, {Bu4N[FeIIH3buea]·2MeCN}2, and {Bu4N[FeIIH22]·MeCN}2. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html, or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: (+44) 1223-336-033; or deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

References

- 1.(a) Werner A. Ann Chem. 1912;386:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Werner A. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1912;45:121. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selected examples: Jameson GB, Molinaro FS, Ibers JA, Collman JP, Brauman JI, Rose E, Suslick KS. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:6769.; Collman JP, Brauman JI, Doxsee KM, Halbert TR, Bunnenberg E, Linder RE, Lamar GN, Del Gaudio J, Lang G, Spartalian K. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:4182.; Collman JP, Brauman JI, Iverson BL, Sessler JL, Morris RM, Gibson QH. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:6245.; Momenteau M, Reed CA. Chem Rev. 1994;94:659.; Wuenschell GE, Tetreau C, Lavalette D, Reed CA. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:3346.; Chang CK, Liang Y, Avilés G, Peng SM. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4191.; Yeh CY, Chang CJ, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1513. doi: 10.1021/ja003245k.; Some non-heme examples from Rivas and Berreau: Mareques-Rivas JC, Prabaharan R, de Rosales RTM. Chem Commun. 2004:76. doi: 10.1039/b310956a.; Berreau LM, Allred RA, Makowski Grzyska MM, Arif AM. Chem Commun. 2000:1423.; Berreau LM, Makowska MM, Grzyska MM, Arif AM. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:2212. doi: 10.1021/ic001190h.; Sigman JA, Kim HK, Zhao X, Carey JR, Lu Y. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA. 2003;100:3629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737308100.; Lu Y. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9930. doi: 10.1021/ic052007t.; Lu Y, Yeung N, Sieracki N, Marshall NM. Nature. 2009;460:855. doi: 10.1038/nature08304.; Lu Y, Berry SM, Pfister TD. Chem Rev. 2001;101:3047. doi: 10.1021/cr0000574.; Natale D, Mareque-Rivas JC. Chem Commun. 2008:425. doi: 10.1039/b709650j.

- 3.(a) Shook RL, Borovik AS. Chem Commun. 2008:6095. doi: 10.1039/b810957e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Borovik AS. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:54. doi: 10.1021/ar030160q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shook RL, Borovik AS. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:3646. doi: 10.1021/ic901550k. and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Lucas RL, Zart MK, Murkherjee J, Sorrell TN, Powell DR, Borovik ASJ. Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15476. doi: 10.1021/ja063935+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mukherjee J, Lucas RL, Zart MK, Powell DR, Day VW, Borovik AS. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:5780. doi: 10.1021/ic800048e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connelly NG, Geiger WE. Chem Rev. 1996;96:877. doi: 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shirin Z, Hammes BS, Young VG, Jr, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:1836. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray M, Golombek AP, Hendrich MP, Young VG, Jr, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6084. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macbeth CE, Hammes BS, Young VG, Jr, Borovik AS. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:4733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, Rijn JV, Vershoor GC. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1984:1349. [Google Scholar]; (b) Atwood David A, Hutchison Aaron R, Zhang Yuzhong. Structure and Bonding: Compounds Containing Five-Coordinate Group 13 Elements. Vol. 105. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Hiedelberg: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zart MK, Sorrell TN, Powell D, Borovik AS. Dalton Trans. 2003:1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Other examples of Fe complexes with the ligand [H3buea]3− and [H22]3− MacBeth CE, Golombek AP, Young VG, Yang C, Kuczera K, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. Science. 2000;289:938. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.938.; MacBeth CE, Gupta R, Mitchell-Koch KR, Young VG, Lushington GH, Thompson WH, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2556. doi: 10.1021/ja0305151.; Larsen PL, Gupta R, Powell DR, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6522. doi: 10.1021/ja049118w.; Lacy DC, Gupta R, Stone KL, Greaves J, Ziller JW, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12188. doi: 10.1021/ja1047818.; Lucas RL, Powell DR, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11596. doi: 10.1021/ja052952g.

- 13.Shirin Z, Young VG, Jr, Borovik AS. Chem Commun. 1997:1967. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng GK-Y, Ziller JW, Borovik AS. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:7922. doi: 10.1021/ic200881t.. In this system, we observed differences in coordination chemistry with Mn(II), Fe(II), and Co(II) despite the fact that the same ligand was used.