Abstract

This article explores gendered patterns of online dating and their implications for heterosexual union formation. The authors hypothesized that traditional gender norms combine with preferences for more socially desirable partners to benefit men and disadvantage women in the earliest stages of dating. They tested this with 6 months of online dating data from a mid-sized southwestern city (N = 8,259 men and 6,274 women). They found that both men and women tend to send messages to the most socially desirable alters in the dating market, regardless of their own social desirability. They also found that women who initiate contacts connect with more desirable partners than those who wait to be contacted, but women are 4 times less likely to send messages than men. They concluded that socioeconomic similarities in longer term unions result, in part, from relationship termination (i.e., nonreciprocity) rather than initial preferences for similar partners.

Keywords: assortative mating, gender, homogamy, online dating, social desirability

The tendency for spouses to resemble each other across a variety of valued social characteristics, including income, education, and health, is a strong and consistent finding among heterosexual married Americans (Kalmijn, 1991; Schwartz & Mare, 2005). This homogamy is of central concern for family and stratification scholars because of its importance for intergroup social distance, inequality among families, and the intergenerational transmission of (dis)advantage (Kalmijn, 1991; Mare, 1991). Although its roots may lie in postmarital processes, such as higher divorce rates among heterogamous marriages or increased spousal resemblance later in life, research suggests that assortative mating into marriage drives observed patterns of homogamy (Schwartz & Mare, 2012). Thus, understanding partner selection processes in the earliest stages of relationships will likely provide key insights into population-level patterns of inequality.

Prior studies of assortative mating have commonly relied on surveys or census data of married, cohabiting, or dating couples and therefore omit important pre-relationship dynamics (England, 2004). By beginning with established relationships, such studies miss initial romantic gestures that hold valuable clues for partner preferences and the origins of relationship stratification. In this study, we extended a burgeoning literature of online dating to analyze 6 months of solicitations and contact patterns for all active daters on a popular online dating site in a mid-size metropolitan area. These data provide the unique opportunity to analyze men's and women's decisions in the earliest stages of relationship formation and allowed us to test several hypotheses about gender, partner preferences, and mate selection.

Online Dating Basics

Because we assert that online dating data provide a unique window into early partnering decisions, an overview of this growing dating market is warranted before we present our hypotheses. Over the past decade, online dating has become a highly visible and common strategy for mate selection (Sautter, Tippett, & Morgan, 2010). Rosenfeld and Thomas (2012) recently conducted a nationally representative longitudinal survey of how couples meet and stay together” and found that online dating is the fastest growing means for unmarried couples to meet. Among sampled heterosexual couples who met in 2009 (the last year of the survey), 22% met their partner online. Moreover, the authors found that online dating is displacing traditional forms of meeting, such as family, friends, and work, while resulting in relationships of similar quality. The increased use and decreased stigma of online dating, along with the rich data collected by online dating companies, make it a useful area for understanding the preliminary stages of union formation.

There is considerable variability in how online dating websites work: Some charge users to participate (Match.com), others are free (okCupid.com); some target a wide audience, others aim at particular subgroups (e.g., religiously affiliated sites like JDate); some emphasize self-directed partner searches (e.g., Match.com), others rely on scientific algorithms for partner selection (e.g., eHarmony; see Finkel, Eastwick, Karney, Reis, & Sprecher, 2012, for a review). The dating website associated with this study is free and open to all singles. The site uses an algorithm to suggest potential matches but also allows users to search among all visible profiles.

The online daters of our study followed steps typical of most online dating sites. First, they were required to create profiles that were then posted on the dating website. Profiles consisted of predefined personal and demographic fields (e.g., age, race, education, body type, smoking), and open-ended essays (e.g., “The first thing people notice about me . . .”). Users were also asked to report their partner gender and age preference, location (near where they live, or anywhere), and nature of the relationship desired (friend, short-term or long-term dating, casual sex). Finally, users were encouraged to upload pictures. Once registered, daters were free to view any profile at any time, or to view a list of profiles suggested by the dating platform based on shared characteristics. If a user was interested in contacting another profile, he or she could send either a message directly to the user or a “wink,” which the receiver got in his or her inbox along with a link to the sender's profile. Regardless of message type, the receiver could respond or not, and nonresponse was common. Should the contact be reciprocated, the couple could exchange messages until the communication was terminated or an in-person meeting was arranged.

Compared to offline dating, initiating online dating requests reduces the fear of rejection in four ways: by (a) eliminating face-to-face interactions at the time of solicitation, (b) reducing the social stigma of rejection through anonymity, (c) providing alternative attributions for nonresponse other than rejection (e.g., “She didn't see the message,” “Did I send her my contact information?”, etc.), and (d) eliminating rejection due to dating unavailability (i.e., all members of the online dating community have signaled that they are available to date). A lower fear of rejection can be a substantial attraction for joining an online dating site and should increase the number of new solicitations relative to those found offline (Rosenfeld & Thomas, 2012).

Reduced rejection fears and access to tens of thousands of available dating partners do not mean that online dating is a panacea for exiting singlehood. More options and message activity do not necessarily translate into better choices (Finkel et al., 2012; Wu & Chiou, 2009; Yang & Chiou, 2010). Experimental data suggest that more options mean more searches, thus offsetting some of the efficiencies associated with online dating. Moreover, more searches can increase cognitive load, translating into more mistakes in the search process. Excessive searching can also alter the way users see potential partners, making them distracted by attributes (e.g., looks) that might matter less to relationship quality (Wu & Chiou, 2009; Yang & Chiou, 2010). Finally, the absence of a trusted broker (e.g., friend, family member) may also undermine the quality of matches made online (Rosenfeld & Thomas, 2012). The limits of online dating mean that it may never fully displace traditional dating strategies or that couples who meet online are more stable than those who meet offline. However, its growth and decreased stigma also suggest that it will not disappear anytime soon and that it has become an important site for understanding modern coupling and gendered partner preferences.

Social Desirability and Partner Preferences: Who Seeks Out Whom?

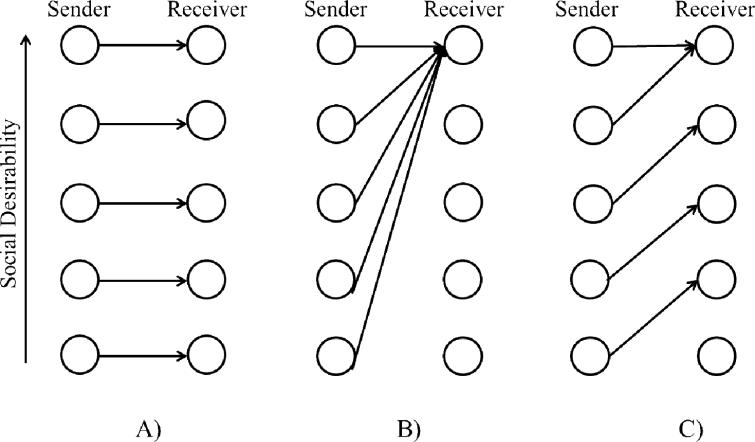

In social psychology, the matching hypothesis (Walster, Aronson, Abrahams, & Rottman, 1966) states that both men and women are strategic in their mate selection, typically seeking partners whose social desirability closely resembles their own because such selections are most likely to achieve better matches (see Figure 1, Panel A). This hypothesis is consistent with observed rates of marital homogamy, whereby spouses are likely to share a wide range of sociodemographic and personal characteristics (Mare, 1991; Schwartz & Mare, 2012).

Figure 1.

Three Models of Partner Desirability Preferences.

The majority of experimental studies primarily focus on physical attractiveness and fail to support the matching hypothesis, instead finding that daters prefer more attractive partners regardless of their own attractiveness (Curran & Lippold, 1975; Hitsch, Hortascu, & Ariely, 2010a, 2010b; Lee, Loewenstein, Ariely, Hong, & Young, 2008; Walster, 1970). For example, Hitsch and colleagues (2010a, 2010b) provided an innovative test of vertical preferences in the online dating context. For each person in their sample of more than 5,000 male and female online daters, they compared the rated physical attractiveness of the dater to the rated physical attractiveness of profiles the dater browsed and did, or did not, send an initial contact. They found that, for both male and female daters, the probability of sending an e-mail to a browsed profile increased with the profile's physical attractiveness, regardless of the daters’ own attractiveness (Hitsch et al., 2010a). Rather than homophilous preferences for physical attractiveness, the evidence suggests that online daters aim high, display vertical preferences, and seek partners who are more attractive than themselves.

We assert that such vertical preferences are also likely to extend to other commonly valued characteristics, such as income, intelligence, humor, and sociability. Consistent with its original formulation, the matching hypothesis defines social desirability as the sum of individuals’ “social assets,” such as “physical attractiveness, popularity, personableness, and material resources” (Berscheid, Dion, Walster, & Walster, 1971, p. 174). Prior studies that have focused on physical attractiveness alone not only departed from the original theory but also gave rise to issues of measurement validity, given that physical attractiveness ratings could vary widely among both raters and surveyed respondents (Montoya, 2008). Moreover, if preferences for physical attractiveness differ substantially by gender, then partner dissimilarity in attractiveness does not preclude similarity in gender-specific social desirability. For example, if a woman trades her physical attractiveness for a man's financial success (e.g., Becker, 1981), then attractiveness asymmetries would be large but social desirability differences would be small.

In this study, we defined men's and women's social desirability on the basis of the subjective evaluations of other daters in the dating market. We expected that daters’ social desirability ratings would capture physical attractiveness along with relatively fixed characteristics that daters bring to the online dating market, weighted by the value of those characteristics to the typical online dater.

Given our measurement of social desirability, how high might daters aim? If all sent messages go to the most socially desirable daters, regardless of the senders’ desirabilities, then the distribution of received ties will be highly concentrated among a select few men and women (see Figure 1, Panel B). Such a skewed distribution may be offset by the low likelihood of response from the most desirable daters, particularly to less desirable senders (Schaefer, 2012). Perhaps a better strategy would be to aim for alters who are only slightly more desirable than oneself, thus maximizing the chances of creating an exchange with a more attractive partner (see Figure 1, Panel C). Such a strategy should also attenuate the concentration of messages to individuals at the highest levels of social desirability and increase activity of daters at all attractiveness levels.

We should note that our social desirability measure captures global, rather than specific, dater attributes. This distinction is important for understanding homophily dynamics because preferences for globally desirable partners do not preclude homophilous preferences for specific profile characteristics. For example, smoking may not contribute to global social desirability but may be highly valued by daters who smoke (Fiore & Donath, 2005). Other characteristics, such as drinking or religion, may then create subgroups in dating markets and be associated with homophilous preferences. In fact, Hitsch and colleagues (2010b) found that income and attractiveness were vertical preferences but attributes like age, race, smoking, and height tended to be more homophilous, with respondents valuing others’ characteristics differently depending on their own. Thus, we expected that smokers would prefer to date more desirable smokers, tall women would prefer to date more desirable tall men, and so on. In other words, even when dater characteristics are accounted for, the principle of vertical preferences may continue to operate.

Initiator Advantages in Dating Markets

If vertical preferences are the norm, online daters who initiate contacts will send messages to more desirable others. At the same time, those who wait to respond to messages will generally have a less desirable pool from which to choose. Moreover, received messages from less desirable alters may encourage passive daters to downwardly adjust their preferences and accept less-than-optimal partners (Kenrick & Gutierres, 1980). Thus, contact initiators may gain an advantage in online dating.

Research suggests that initiator advantages are common in price negotiations, where buyers or sellers who provide initial offers achieve more advantageous outcomes than those who respond to initial offers (Galinsky & Mussweiler, 2001; Liebert, Smith, Hill, & Keiffer, 1968). The mechanism thought to explain the initiator advantage is that first offers serve as judgmental anchors that favor initiators in situations of uncertainty (Kahneman, 1992; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Accordingly, initial-offer recipients are believed to apply a cognitive heuristic whereby past perceptions are updated to become consistent with the offer. This perceptual updating process will favor offer initiators, because initial offers are likely below receivers’ desired price points. For example, home sellers with incomplete housing market knowledge may downwardly adjust their perceived home values based on potential buyers’ low initial offers and subsequently downwardly adjust their counteroffers based on revised estimates. The results are less-than-optimal negotiation outcomes from the sellers’ perspectives.

The anchoring effects of initial offers can easily be applied to dynamic dating markets. Daters’ judgments of their own social desirability, or “value” in the dating market, are inherently uncertain and influenced by market conditions and subjective experiences. The desirability of suitors who initiate dating requests may become anchors for receivers’ self-evaluations and perceived market desirability (Back et al., 2011). In the aggregate, passive online daters may adjust their perceptions of self, as well as a desirable mate, on the basis of the pool of received dating requests. This adjustment would be favorable to passive daters who receive requests from more desirable suitors, and unfavorable if the requests originate from less desirable suitors. Yet, given vertical preferences, if a dater is passive and receives requests only from less desirable partners, then selecting the best partner from that pool will still be less than optimal given the dater's objective market positions.

Similarly, initiators benefit in dating markets to the extent that they aim high. Providing an initial offer to a more socially desirable partner increases the likelihood of a response if that partner's subjective evaluation has been anchored by previous requests from less desirable suitors. From the receiver's perspective, the initiator would then be an acceptable, but not optimal, choice. The initiator would “get lucky” by creating a contact with a partner of higher desirability than him or her.

It is important to note that initiating relationships, either online or off, remains a gendered process. In face-to-face and online dating situations, women are less likely to initiate contacts compared to men (England & Thomas, 2006; Fiore & Doneth, 2005; Hitsch et al., 2010a; Laner & Ventrone, 2000; Sassler & Miller, 2011). Thus, because more men initiate contacts than women, men are also more likely to benefit from an initiator advantage. What remains less clear is whether women who initiate contacts benefit too.

Homophily as a Process

If senders have a preference for more desirable partners, what explains the homogamy typically observed in long-term relationships? One possibility is that structural segregation in real-world dating markets restricts individual choices to partners with similar characteristics, particularly at points in the life course when unions are most likely to occur (England, 2004; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). For example, college and work are domains increasingly segregated by race, class, and cultural characteristics, meaning that relationships that begin there are likely between socioeconomically similar partners. An interesting aspect of online dating, however, is that such structural barriers are substantially reduced once daters have online access (Rosenfeld & Thomas, 2012). Online, partner choices should better reflect actual preferences rather than structural constraints or baseline levels of homophily (Hitsch et al., 2010a).

An alternative explanation for homogamy that remains consistent with vertical preferences and the initiator advantage is that it is induced through the iterative social exchange process (Schaefer, 2012; Sprecher, 1998; Thibaut & Kelly, 1959). In competitive dating markets with vertical preferences, message responders should choose the most desirable partners from their (less-than-optimal) pool of received messages, which should most closely resemble themselves. This winnowing process should increase homophily at each stage of dating due to nonreciprocity, resulting in long-term couples with similar social desirability levels (Schwartz, 2010; Taylor, Fiore, Mendelsohn, & Cheshire, 2011). Kalick and Hamilton (1986) demonstrated this process in a simulation in which all actors were assumed to desire partners of greater attractiveness. They found that the resulting homophily levels were equal to simulations in which partners were assumed to desire more homophilous partners and were comparable to real-world homogamy levels.

More recently, Schaefer (2012) found a similar pattern of homophily arising in a computer-based exchange game. In his experiment, homophily among low-value participants arose because of the nonreciprocity of high-value participants to initial gestures. In other words, low-value participants adjusted their preferences over time because of nonresponse. Finally, Skopek and colleagues (Skopek, Florian, & Blossfeld, 2011) looked at iterative exchanges and educational homophily using German online dating data. They found that women were particularly reluctant to return messages from lower educated men, thus increasing educational homophily through nonreciprocity.

We hypothesized a similar mechanism for social desirability homophily through nonreciprocity, whereby couples of similar social desirability have a greater chance of persisting than dissimilar couples. We tested this by examining the similarities among couples over time during early online dating exchanges. We contend that asymmetrical couples are more likely to dissolve than symmetrical couples over repeated online exchanges before a first real-world date. The effect of nonreciprocity would be most apparent at the point of responding to first requests. Daters who receive requests from less desirable partners should be less likely to respond than daters who receive requests from similarly desirable partners, increasing homophily at the point of first exchange. This process of increasing couple similarity should continue through each message exchange, so that dyads who persist should be more homophilous than the population of dyads with an unreciprocated first contact. Such findings would provide evidence suggestive of iterative homophily at the earliest stages of relationship formation.

Method

Data

We tested our hypotheses with data from a national online dating company collected over a 6-month period in 2010–2011 in one mid-sized southwestern city. The dating company stripped the data of names, assigned each profile a unique identifier, and withheld all free-form profile text and message content that might include personally identifiable information. Each message record was date-stamped, allowing for the temporal ordering of message exchanges.

Our analyses are based on a sample of 8,259 male and 6,274 female online daters. All users identified themselves as single and heterosexual, had active profiles (i.e., they filled in at least the profile text and sent or received messages) within a 6-month window in 2011, resided in one of the metropolitan area's zip codes, and were rated on their attractiveness (see below) by other users. The overwhelming majority of users (73%) were interested in finding a dating partner, some (22%) were looking for friendships, and less than 1% were interested in sexual partnerships. In the observed time period, users sent 177,404 first contacts (either e-mail messages or “winks”) to other users within the city limits. Of these, 142,444 were sent by men and 34,960 were sent by women: a 4-to-1 male-to-female ratio. Consistent with prior research, we thus found evidence of a strong gendered pattern of sent contacts, whereby men are much more likely than women to initiate a contact.

Measures

In this study, we defined men's and women's social desirability on the basis of the subjective evaluations of other daters in the market. We operationalized online social desirability with average profile ratings from opposite-gender daters. These ratings were derived from a system-generated matching tool that presents users with a series of dater profiles and pictures (randomly assigned after accounting for gender, age, location, and relationship preferences) that are then rated on a 5-star scale of attractiveness (1 = least attractive to 5 = most attractive). These ratings can be averaged for each dater to provide an indicator of his or her global desirability in the dating market. In our data, each active dater was evaluated by an average of 180 other users, increasing our confidence in the measure's reliability. An added advantage of this measure is that it is not dependent on users’ online activity. Once a dater creates a profile, it is available to be evaluated by other daters, and these evaluations do not depend on the evaluations of others or the evaluated dater's incoming or outgoing activity. We thus argue that attractiveness ratings capture the sum of relatively fixed characteristics that daters bring to the online dating market, weighted by the desirability of those characteristics by the typical online dater. Approximately 5% of the users were not rated on their attractiveness, likely because they had recently entered the dating market. These raters were excluded from the analyses.

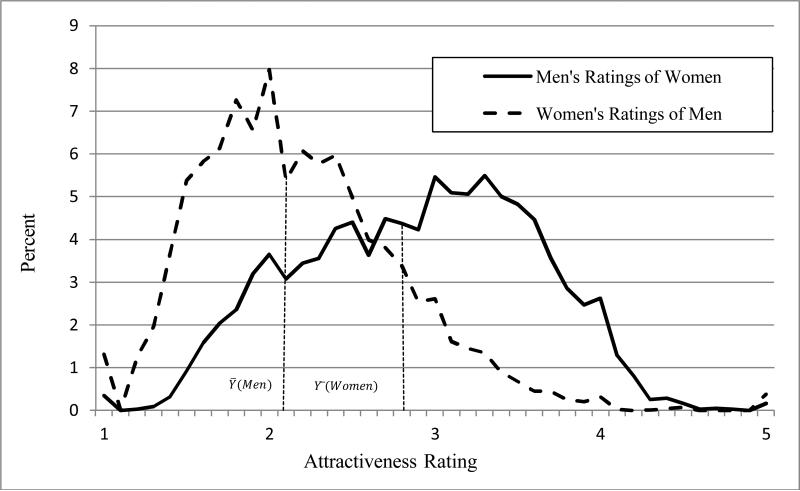

An examination of the gender distributions showed both to be unimodal, but the mean was greater for men's evaluations of women (Ȳ = 2.84) than women's evaluations of men (Ȳ = 2.13), and the skew was greater for women's evaluations of men (σ = .70) than for men's evaluations of women (σ = .61; see Table 1 and Figure 2). In other words, on average, men evaluated women's attractiveness higher than women evaluated men's, but women's evaluations of men were more tightly clustered than vice versa. For descriptive analyses of the correlates of men's and women's desirability, we standardized the ratings within gender with a z-score transformation (see Table 2). To ease gender comparisons in heterosexual dyads, we also divided the ratings into five equal categories (high, medium-high (med-high), medium, med-low, and low), each containing 20% of men's or women's desirability rankings.

Table 1.

Profile-Level Variable Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | Men (N = 8,259) | Women (N = 6,274) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/% | SD | M/% | SD | |

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Attractiveness ratinga | 2.13 | 0.61 | 2.84 | 0.70 |

| Profile characteristics | ||||

| Birth year | 1979 | 9.40 | 1979 | 10.17 |

| Race | ||||

| White (ref.) | .61 | .62 | ||

| Black | .04 | .04 | ||

| Hispanic | .13 | .13 | ||

| Other race | .11 | .09 | ||

| Missing race | .11 | .12 | ||

| Body type | ||||

| Average (ref.) | .28 | .26 | ||

| Athletic (also fit) | .36 | .16 | ||

| Thin (also skinny) | .10 | .12 | ||

| Overweight (also obese, fleshy, big boned, full figured, jacked) | .10 | .28 | ||

| Missing body type | .16 | .18 | ||

| Height (decile) | 5.98 | 2.80 | 5.85 | 2.84 |

| Missing height | 0.13 | 0.14 | ||

| Education | ||||

| 4-year degree (ref.) | .52 | .52 | ||

| High school | .05 | .04 | ||

| Some college | .08 | .06 | ||

| Postgraduate | .13 | .17 | ||

| Missing education | .22 | .21 | ||

| Current student | .25 | .28 | ||

| Missing current student | .17 | .16 | ||

| Drinks | .74 | .76 | ||

| Missing drinks | .08 | .09 | ||

| Smokes | .25 | .22 | ||

| Missing Smokes | .12 | .12 | ||

| Profile length | 8.69 | 4.45 | 8.15 | 4.41 |

| Number of photos | 7.51 | 8.38 | 7.11 | 7.42 |

| Dating activity | ||||

| Outgoing messages | 21.02 | 51.73 | 8.61 | 13.75 |

| No outgoing messages | 0.15 | 0.31 | ||

| Incoming messages | 5.47 | 6.77 | 24.79 | 30.13 |

| No incoming messages | 0.18 | 0.02 | ||

Note: ref. = reference category.

On a scale that ranged from 1 (least attractive) to 5 (most attractive).

Figure 2.

Attractiveness Ratings of Online Daters.

Table 2.

Regressions of Rated Desirability on Profile Characteristics

| Profile characteristics | Women's ratings of men's desirability | z testa | Men's ratings of women's desirability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | ||

| Birth year | –.008*** | .001 | *** | .003*** | .001 |

| Race | |||||

| White (ref.) | |||||

| Black | –.628*** | .056 | ** | –.863*** | .055 |

| Hispanic | –.253*** | .031 | * | –.139*** | .033 |

| Other race | –.291*** | .033 | *** | .048 | .039 |

| Missing race | –.082** | .045 | *** | .114* | .045 |

| Body type | |||||

| Average (ref.) | |||||

| Athletic | .366*** | .026 | .421*** | .035 | |

| Thin | .214*** | .038 | *** | .513*** | .038 |

| Overweight | –.376*** | .037 | *** | –.714*** | .030 |

| Missing body type | –.012 | .036 | *** | –.273*** | .038 |

| Height (quintile) | .026*** | .004 | *** | .004 | .005 |

| Missing height | –.063 | .043 | –.101* | .044 | |

| Education | |||||

| 4-year degree (ref.) | |||||

| High school | –.274*** | .048 | –.267*** | .055 | |

| Some college | –.253*** | .039 | –.198*** | .046 | |

| Postgraduate | .066 | .032 | ** | –.076*** | .031 |

| Missing education | –.070 | .039 | .000 | .047 | |

| Current student | .069** | .026 | .039 | .027 | |

| Missing current student | .007 | .045 | .014 | .053 | |

| Drinks | .109*** | .028 | .199*** | .031 | |

| Missing drinks | .083 | .060 | .177* | .065 | |

| Smokes | –.071*** | .025 | –.003 | .028 | |

| Missing smokes | .060 | .046 | .126* | .049 | |

| Profile length | .010*** | .003 | *** | –.004 | .003 |

| Number of photos | .008*** | .001 | ** | .015*** | .002 |

| Intercept | 14.665*** | 2.359 | –6.180*** | 2.332 | |

| N | 8,190 | 6,244 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | .14 | .27 | |||

Note: Coef. = coefficient; ref. = reference category.

p value from z test of cross-gender coefficient equality (Clogg et al., 1995).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed).

Other dater characteristics were taken from users’ responses (see Table 1). The average age of men and women active on this dating site was 32 years, with 82% of the sample under age 40. Users were permitted to select more than one racial category (White, Black, Hispanic, other race, missing). More than 60% reported being White. Educational attainment was captured with five categories: (a) 4-year degree (reference), (b) high school degree, (c) some college, (d) postgraduate, and (e) missing. Just over half of the sample reported being a college graduate, and one quarter were missing information on education. It is noteworthy that over one quarter of the daters were students. This is likely because the dating service is free of charge and the city is home to a large university. It is clear that this city's online dating population is highly educated and fairly homogeneous with regard to race. This is consistent with Sautter et al.'s (2010) finding that online daters comprise a relatively advantaged subpopulation with Internet access and computer literacy. The “Whiteness” of this dating population has strong implications for the perceived attractiveness of members of racial/ethnic minority groups. Hitsch et al. (2010b) found a strong preference for same-race partnerships for both male and female online daters. Combined with a high proportion of Whites in our dating market, homophilous racial preferences are likely to result in daters who are members of racial/ethnic minority groups being perceived as less desirable.

Also, several constructed variables combine multiple response categories. Athletic Body Type includes “athletic,” “fit,” and “jacked.” Thin Body Type includes “thin” and “skinny.” Overweight Body Type includes “overweight,” “obese,” “fleshy,” “big boned,” and “full figured.” Drinks is coded as 0 if the dater selects “rarely” or “never” and 1 if he or she selects “very often,” “often,” “socially,” or “desperately.” Smokes is coded 0 if the dater selects “no” and 1 if he or she selects “yes,” “sometimes,” “when I drink,” or “trying to quit.”

Although we were not provided actual text or pictures from the online dating company, we did receive a count of words included in each user's profile and a count of pictures uploaded. We included these as indicators of a user's investment in the dating site.

We also include two summary measures of online dating activity. Outgoing Messages captures the total number of messages sent by the online daters in the sixth-month observation window. The average male sent about 2.5 times as many messages than the average woman, and the male distribution of sent messages was much more highly skewed. In addition, twice as many women as men sent no messages to other daters. Incoming Messages showed the opposite pattern, with the average male receiving 4.5 times fewer messages than the average woman, and 10 times more men compared to women receiving no messages. Nearly all women (98%) received at least one message from a man, and about 18% of men received no messages from women.

The message-level characteristics for messages initiated by men (N = 142,444) and by women (N = 34,960) are shown in Table 3. Time order is a variable that captured the order in which messages were sent (or received). Messages sent (or received) on the same day were assigned the same value. The average man sent messages on 16 different days, whereas the average woman sent messages on seven different days. We included this to determine whether senders aimed for partners of similar desirability over time or adapted their preferences on the basis of online dating experiences. Four variables indicated the number of times that an initiated message was reciprocated by the receiver of the message. Seventy-nine percent of men's sent messages, and 58% of women's sent messages, went unreciprocated. As the number of reciprocated responses increased, the percentage of messages in each category declined, so that only 3% of men's, and 7% of women's, sent messages resulted in more than five exchanges. The last category captured the mean number of exchanges (six) required until the relationship resulted in an offline date by Hitsch et al. (2010a). Obviously, the likelihood of any given message resulting in a reciprocated exchange and eventual date is extremely small.

Table 3.

Message-Level Variable Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Male initiated (n = 142,444) | Female initiated (n = 34,960) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/% | SD | M/% | SD | |

| Time order | 16.49 | 22.84 | 7.13 | 8.83 |

| Message not reciprocated (ref.) | .79 | .58 | ||

| Reciprocated 1 time | .10 | .18 | ||

| Reciprocated 2–5 times | .08 | .17 | ||

| Reciprocated >5 times | .03 | .07 | ||

Note: ref. = reference category.

Analytical Strategy

We tested our hypotheses in three steps. First, to explore the gendered criteria associated with social desirability and compare these to the results of prior research, we predicted the continuous measure of desirability within gender using ordinary least squares regression with profile characteristics as covariates. Second, we compared sender and receiver desirability values for all sent messages in a cross-tabulation. This provides an initial indication of horizontal or vertical desirability preferences. Third, we conducted a multivariate test for vertical preferences and initiator advantages by comparing sender and receiver desirability ratings, measured on an ordinal scale, in a series of two-level hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

For these models, we approached the data as consisting of groups of sent or received messages nested within individual online daters. Male and female daters may send messages to, or reply to received messages, from the same opposite-sex alters, but their online decisions are independent and unbeknownst to one another. We could therefore compare each dater's own desirability to the desirabilities of his or her alters. Our HGLM analyses consisted of random-intercept models predicting the desirability of message receivers and the desirability of message senders. Note that models of receiver and sender desirability are not inverses of one another. Each dater has his or her own set of sent or reply messages, so each analysis consists of distinct message groupings per dater. In addition, our models compared not the characteristics of chosen and not-chosen alters (a network or discrete-choice question) but rather characteristics of chosen alters to those of the ego and other alters. Such a strategy is capable of addressing our hypotheses of vertical preferences and social exchange.

Users are required to fill out only gender, location, and age to gain access to the dating site. Other characteristics had missing values ranging from 8% (men's drinking status) to 22% (women's educational attainment). Because missing values likely indicate (nonrandom) choices by daters not to present their personal information, we did not impute missing values but included missing-value indicators in all regression analyses.

Results

Correlates of Attraction

Estimates from standard ordinary least squares regressions of individuals’ rated attractiveness, by daters’ gender, are listed in Table 2. In this dating market, men who are White, athletic or thin, tall, well educated, drinkers, and nonsmokers are the most desirable to female raters. Female online daters perceived as attractive by their male counterparts show many of the same characteristics, but gender differences are strongest for age, height, race, and education. Men prefer younger women, whereas women prefer older men. Women prefer taller men, whereas men do not show a strong preference for women's height. With respect to race, Black women are penalized more than Black men, whereas Hispanic men are penalized more than Hispanic women. For education, women with postgraduate degrees are rated as significantly less attractive than men with similar education. This provides some support for a continued double standard for successful women versus successful men. Also interesting is that women prefer longer profiles than men, whereas men prefer more photos than women. These findings suggest a gendered preference for looks over written communication skills and cultural interests. In sum, several characteristics are globally attractive for male and female online daters in the sampled city (e.g., thinner bodies and drinking), but several gender differences also exist. The differences provide further evidence for standardizing values within gender when we compared men's and women's partner social desirability levels. Gender differences in age, height, race, and education were also found in Hitsch et al.'s (2010a, 2010b) studies of online dating, building our confidence that the rated attractiveness measures provide adequate proxies of men's and women's dating market value.

Comparing Sender and Receiver Desirability

In Table 4 we divide men's and women's desirability ratings into quintiles and present the percentages of sent messages for each sending and receiving combination (i.e., the row percentages sum to 1), by sender gender. If the matching hypothesis is accurate and daters prefer similarly desirable partners, we would expect the diagonal cells to be most represented. If the “aim highest” hypothesis is accurate, the left-most column in each row should be largest. And if daters temper their vertical preferences by aiming just above themselves, then the cells just below the diagonal should be most represented. For both male and female senders, the evidence lies between the aim-highest and tempered hypotheses. The modal category for male and female sent messages is to the highest desirability category, regardless of the sender's desirability level. Indeed, there is some evidence that less desirable women are more likely to aim higher than less desirable men. There is also some evidence that male and female senders in the lower desirability levels vary their sent messages to desirability categories below the highest (but for the most part above their own desirability level), perhaps to increase the likelihood of a response. In sum, this initial analysis showed strong evidence of vertical preferences, with the majority of sent messages going to the most desirable daters in the market.

Table 4.

Distribution of Sent Messages by Sender–Receiver Desirability Ratings (Row Percentages)

| Female receiver | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium-high | Medium | Medium-low | Low | ||

| Male sender | High | .58 | .25 | .10 | .05 | .02 |

| Medium-high | .43 | .33 | .15 | .07 | .02 | |

| Medium | .34 | .27 | .23 | .12 | .04 | |

| Medium-low | .30 | .23 | .20 | .20 | .07 | |

| Low | .29 | .21 | .16 | .18 | .16 | |

| Male receiver | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium-high | Medium | Medium-low | Low | ||

| Female sender | High | .62 | .20 | .10 | .05 | .03 |

| Medium-high | .52 | .26 | .13 | .06 | .02 | |

| Medium | .47 | .25 | .18 | .08 | .02 | |

| Medium-low | .37 | .24 | .20 | .14 | .05 | |

| Low | .30 | .22 | .20 | .18 | .10 | |

Predicting Receiver Desirability

In our next set of analyses we examined this association with a more sophisticated modeling strategy that adjusted for between-person differences in message activity and profile characteristics. Coefficient estimates of four multilevel models predicting the ordinal measure of receiver desirability for all sent messages in our sample are listed in Table 5. To ease interpretations of the intercept and interactions, we centered all continuous measures around their global means. Our model progression begins with Model 1, including senders’ gender, measures of online activity, and desirability value and message-level characteristics for time ordering and number of reciprocation categories; Model 2 added cross-level interactions of individual-level desirability to the message-level covariates; Model 3 added a list of sender-level (i.e., Level 2) demographic characteristics; and Model 4 added the same demographic characteristics at the receiver level (i.e., Level 1). In unlisted analyses, we also examined gender interactions with our variables of interest, and found none of these to be significant.

Table 5.

Hierarchical Generalized Linear Model Ordered Logistic Regressions of Receiver Desirability

| Covariates | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE a | Coef. | SE a | Coef. | SE a | Coef. | SE a | |

| Sender properties (N = 11,241)b | ||||||||

| Intercept | –1.28*** | 0.03 | –1.24*** | 0.03 | –1.26*** | 0.05 | –1.30*** | 0.05 |

| Total incoming messages | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00** | 0.00 |

| Total outgoing messages | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 |

| Female | 0.27*** | 0.03 | 0.28*** | 0.03 | 0.47*** | 0.03 | 0.18*** | 0.03 |

| Desirability | 0.48*** | 0.01 | 0.46*** | 0.01 | 0.38*** | 0.01 | 0.35*** | 0.01 |

| White (ref.) | ||||||||

| Black | –0.43*** | 0.07 | –0.23*** | 0.06 | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | ||||

| Other race | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | ||||

| Missing race | 0.01 | 0.05 | –0.01 | 0.05 | ||||

| Height (decile) | 0.01** | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||||

| Missing height | –0.13*** | 0.05 | –0.12** | 0.05 | ||||

| Number of photos | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.00** | 0.00 | ||||

| Smokes | –0.04 | 0.03 | –0.02 | 0.03 | ||||

| Missing smokes | 0.21*** | 0.05 | 0.21*** | 0.05 | ||||

| Birth year | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.00 | ||||

| Profile length | –0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.02*** | 0.00 | ||||

| Drinks | 0.19*** | 0.03 | 0.17*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Missing drinks | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.07 | ||||

| 4-year degree (ref.) | ||||||||

| High school | –0.21*** | 0.06 | –0.13* | 0.05 | ||||

| Some college | –0.19*** | 0.04 | –0.15*** | 0.04 | ||||

| Postgraduate | –0.04 | 0.03 | –0.07* | 0.03 | ||||

| Missing education | –0.14** | 0.04 | –0.12** | 0.04 | ||||

| Current student | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | ||||

| Missing current student | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | ||||

| Average body type (ref.) | ||||||||

| Athletic | 0.33*** | 0.03 | 0.28*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Thin | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | ||||

| Overweight | –0.44*** | 0.04 | –0.34*** | 0.04 | ||||

| Missing body type | –0.12** | 0.05 | –0.09* | 0.04 | ||||

| Message properties (N = 177,404)b | ||||||||

| Time order | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Message not reciprocated (Rec.; ref.) | ||||||||

| Rec. 1 time | –0.65*** | 0.02 | –0.69*** | 0.03 | –0.69*** | 0.03 | –0.60*** | 0.03 |

| Rec. 2–5 times | –0.79*** | 0.02 | –1.03*** | 0.03 | –1.03*** | 0.03 | –0.87*** | 0.03 |

| Rec. >5 times | –0.92*** | 0.03 | –1.28*** | 0.05 | –1.28*** | 0.05 | –1.05*** | 0.05 |

| Rec. 1 × desirability | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Rec. 2–5 × desirability | 0.11*** | 0.01 | 0.10*** | 0.01 | 0.07*** | 0.01 | ||

| Rec. >6 × desirability | 0.15*** | 0.02 | 0.15*** | 0.02 | 0.10*** | 0.02 | ||

| Receiver properties (N = 177,404)b | ||||||||

| White (ref.) | ||||||||

| Black | –1.63*** | 0.05 | ||||||

| Hispanic | –0.18*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Other race | –0.06** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Missing race | 0.20*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Height (decile) | 0.02** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Missing height | –0.12*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Number of photos | 0.02*** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Smokes | –0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing smokes | 0.09*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Birth year | –0.01*** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Profile length | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Drinks | 0.17*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing drinks | 0.21*** | 0.03 | ||||||

| 4-year degree (ref.) | ||||||||

| High school | –0.23*** | 0.03 | ||||||

| Some college | –0.35*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Postgraduate | –0.15*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing education | –0.11*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Current student | 0.14*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing current student | 0.15*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Average body type (ref.) | ||||||||

| Athletic | 0.52*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Thin | 0.73*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Overweight | –1.13*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Missing body type | –0.43*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Thresholds | ||||||||

| φ 1 | 1.30*** | 0.01 | 1.30*** | 0.01 | 1.30*** | 0.01 | 1.40*** | 0.01 |

| φ 2 | 2.42*** | 0.02 | 2.43*** | 0.02 | 2.43*** | 0.02 | 2.65*** | 0.01 |

| φ 3 | 3.97*** | 0.03 | 3.98*** | 0.03 | 3.98*** | 0.03 | 4.33*** | 0.03 |

| Level 2 variance | 0.93*** | 0.93*** | 0.84*** | 0.68*** | ||||

Note: Coef. = coefficient; ref. = reference category.

Robust standard errors.

Continuous covariates were centered at their grand means.

Looking first at Model 1, we see that individuals who receive many incoming messages also send messages to more desirable partners (b = .004), whereas those who send many outgoing messages show the opposite pattern (b = −.001). The former suggests that popular daters can be more selective and initiate contacts with the most desirable partners, whereas the latter suggests a “shotgun” approach, whereby individuals who send many outgoing messages tend to sacrifice “quality” by widening their nets to alters at lower desirability levels.

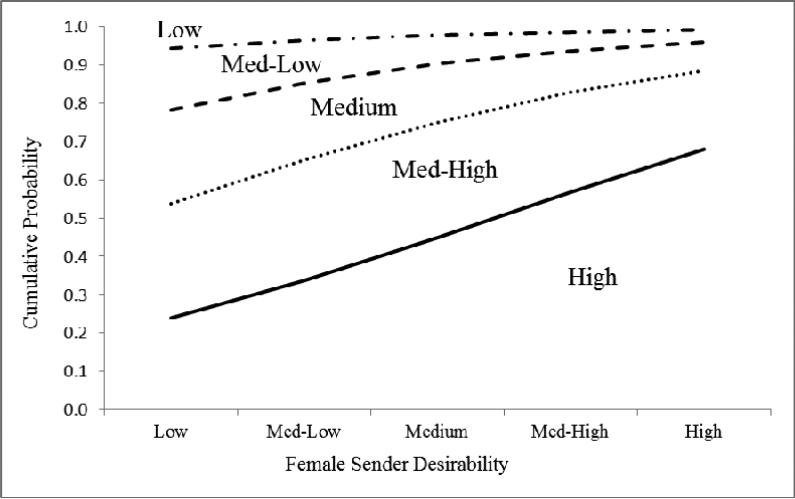

The positive coefficient for sender desirability indicates that more desirable daters send messages to more desirable alters, a pattern that could be consistent with desirability homophily and the matching hypothesis. However, the modest size of this coefficient relative to the intercept and threshold values means that, overall, daters tend to aim higher than themselves. In Figure 3 we help visualize this pattern by plotting the cumulative probabilities of male receiver desirability across the desirability categories of female senders. Figure 3 demonstrates that female daters are more likely to send messages to more desirable alters than to less desirable alters. However, similar to the results of Table 4, Figure 3 shows that not all messages are likely to go to the most desirable online daters. Again, patterns of sent messages appeared to fall between the aim-highest and the more tempered models in Figure 1. This difference is greatest for the least desirable senders, whereby fewer than 10% send messages to men at similar desirability levels and more than half sent messages to alters in the medium-high and highest level quintiles. A ceiling on social desirability means that the highest sender desirability category cannot aim to more desirable alters, but even here the probability of a message going to the top two alter-desirability categories is close to 90%. In sum, these results provide further evidence that senders tend to aim high, regardless of their own desirability.

Figure 3.

Cumulative Predicted Probabilities of Male Receiver Desirability by Female Sender Desirability.

In regard to the message-level covariates, Model 1 suggests that senders are unlikely to change their preferences over time. The time order coefficient was nonsignificant, meaning that senders aim for partners of similar desirability on their first day as on their last day of sending messages. This provides little evidence for adaptive preferences based on online experiences.

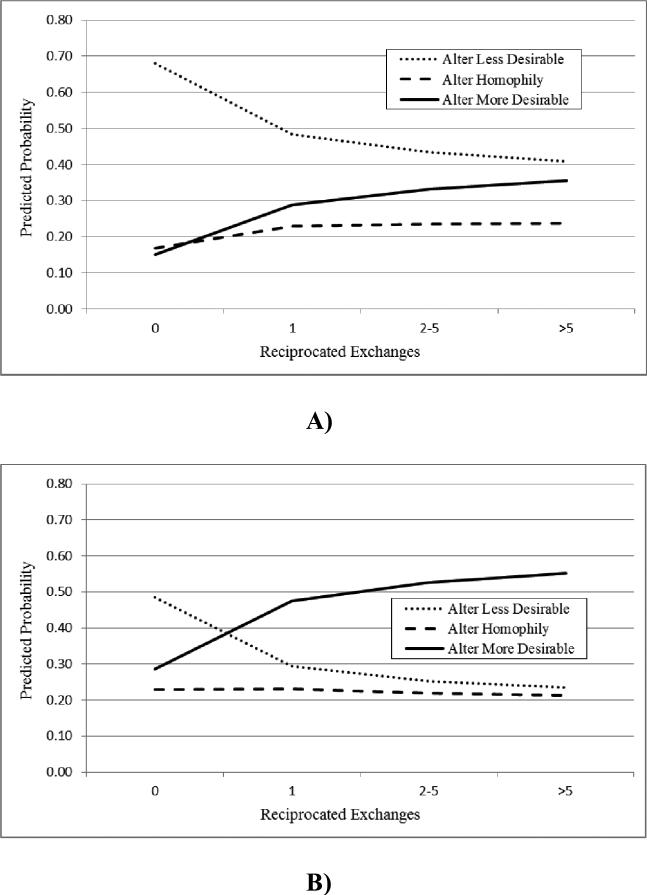

The final three covariates of Model 1 compared receiver desirability ratings across the number of times the message was reciprocated. There appears a monotonic negative association between increased message exchange and receiver desirability. Combined with the vertical-preference finding, the decline in receiver desirability over reciprocated messages suggests increased desirability homophily over time. In Figure 4 we illustrate this association by plotting predicted probabilities of male and female receiver desirability by message reciprocation, net of other factors. The topmost lines in each graph show that the probability of interacting with a more desirable partner decreases over repeated exchanges for both men and women, with the greatest drop occurring after the first reciprocated exchange. Similarly, the second line shows that the probability of a homophilous dyad increases through repeated exchanges. Note that even over extended exchanges (i.e., greater than five), female and male message senders are more likely to remain in contact with more desirable than similarly or less desirable alters. Indeed, even though fewer women send messages than men, women who do initiate contacts are more likely to benefit from this initiator advantage because they initially aim at more attractive targets (i.e., the female coefficient is significant). At the point when prior research suggests that online dating is likely to move offline (i.e., a mean of six messages), women senders have almost a 60% probability of staying connecting to men who are rated more desirable than they are.

Figure 4.

Predicted Probabilities of Receiver Desirability by Reciprocated Exchanges, Average Female (Panel A) and Male (Panel B) Sender.

Model 2 tested whether dater desirability moderates message-level reciprocity. The positive coefficients for these interactions suggest that the decrease in desirability over repeated exchanges is less pronounced as sender desirability increases. This is not surprising, because receivers should be more likely to reciprocate exchanges with more desirable partners.

Model 3 included sender-level profile characteristics in the equation. The primary purpose of this model was to test the robustness of the previous model estimates with additional covariates. As would be expected given the correlation between our desirability measure and profile characteristics, the estimate of sender desirability (b = .48 in Model 1 and b = .38 in Model 3) was somewhat attenuated (14%) with the introduction of other sender attributes. The desirability estimate, however, remained strong and significant, suggesting that this measure also captured unobserved characteristics, such as physical features, cultural knowledge, humor, and intellect, that are related to message sending decisions. The added sender characteristics appeared to suppress the female coefficient by increasing its association with receiver desirability with their inclusion (b = .27 in Model 1 and b = .47 in Model 3). Net of sender characteristics, women are increasingly likely to send messages to more desirable men. The intercept, thresholds, and other parameters are little affected by the introduction of these measures.

The final model added profile characteristics at the receiver level. Again, we were primarily interested in whether our primary independent variables were robust to the added covariates. Although the sender desirability coefficient was attenuated by another 8% (b = .38 in Model 3 and b = .35 in Model 4), the pattern of results and significance levels remained relatively unchanged. The pattern of receiver-level covariates captured correlates of desirability in the dating market, whereby White, younger, college-educated, drinking, and athletic/thin alters were more likely to be perceived as socially desirable.

Predicting Sender Attractiveness

In Table 6 we present estimates of HGLM models of sender desirability that included covariates for message receiver (Level 2) and message level (Level 1) covariates. The model estimates and progression paralleled those for receiver desirability presented above. Note that there are more individuals at Level 2 in these models than in the receiver-desirability models because there are more daters who only receive messages than daters who only send messages.

Table 6.

Hierarchical Generalized Linear Model Ordered Logistic Regressions of Sender Desirability

| Covariates | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE a | Coef. | SE a | Coef. | SE a | Coef. | SE a | |

| Receiver properties (N = 12,730)b | ||||||||

| Intercept | –3.05*** | 0.02 | –2.97*** | 0.02 | –2.94*** | 0.00 | –2.78*** | 0.03 |

| Total incoming messages | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 |

| Total outgoing messages | 0.00** | 0.00 | 0.00** | 0.00 | 0.00* | 0.00 | 0.00** | 0.00 |

| Female | –0.81*** | 0.02 | –0.81*** | 0.02 | –0.84*** | 0.01 | –0.41*** | 0.02 |

| Desirability | 0.53*** | 0.01 | 0.51*** | 0.01 | 0.45*** | 0.01 | 0.39*** | 0.01 |

| White (ref.) | ||||||||

| Black | –0.18*** | 0.04 | –0.01 | 0.04 | ||||

| Hispanic | –0.07** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||

| Other race | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||

| Missing race | 0.13*** | 0.03 | 0.11*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Height (decile) | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Missing height | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||

| Number of photos | 0.00* | 0.00 | 0.00* | 0.00 | ||||

| Smokes | 0.03* | 0.02 | 0.05** | 0.02 | ||||

| Missing smokes | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||

| Birth year | –0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | ||||

| Profile length | –0.01*** | 0.00 | –0.01*** | 0.00 | ||||

| Drinks | 0.06** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||

| Missing drinks | 0.14** | 0.04 | 0.10* | 0.04 | ||||

| 4-year degree (ref.) | ||||||||

| High school | –0.17*** | 0.04 | –0.07* | 0.03 | ||||

| Some college | –0.12*** | 0.03 | –0.06* | 0.03 | ||||

| Postgraduate | 0.03 | 0.02 | –0.04* | 0.02 | ||||

| Missing education | –0.04 | 0.03 | –0.01 | 0.03 | ||||

| Current student | –0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||||

| Missing current student | –0.07* | 0.03 | –0.06* | 0.03 | ||||

| Average body type (ref.) | ||||||||

| Athletic | 0.19*** | 0.02 | 0.14*** | 0.02 | ||||

| Thin | 0.23*** | 0.02 | 0.18*** | 0.02 | ||||

| Overweight | –0.13*** | 0.02 | –0.08*** | 0.02 | ||||

| Missing body type | 0.07** | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 | ||||

| Message properties (N = 177,404)b | ||||||||

| Time order | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Message not reciprocated (Rec.; ref.) | ||||||||

| Rec. 1 time | 0.85*** | 0.02 | 0.74*** | 0.04 | 0.75*** | 0.04 | 0.65*** | 0.04 |

| Rec. 2–5 times | 1.09*** | 0.02 | 0.82*** | 0.04 | 0.83*** | 0.04 | 0.76*** | 0.04 |

| Rec. >5 times | 1.22*** | 0.02 | 0.82*** | 0.05 | 0.85*** | 0.05 | 0.77*** | 0.05 |

| Rec. 1 × attractiveness | 0.04*** | 0.01 | 0.04*** | 0.01 | 0.03** | 0.01 | ||

| Rec. 2–5 × attractiveness | 0.10*** | 0.01 | 0.10*** | 0.01 | 0.08*** | 0.01 | ||

| Rec. >6 × attractiveness | 0.16*** | 0.02 | 0.15*** | 0.02 | 0.12*** | 0.02 | ||

| Sender properties (N = 177,404)b | ||||||||

| White (ref.) | ||||||||

| Black | –1.45*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Hispanic | –0.48*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Other race | –0.56*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Missing race | –0.05* | 0.02 | ||||||

| Height (decile) | 0.08*** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Missing height | –0.16*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Number of photos | 0.00*** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Smokes | –0.14*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing smokes | 0.06** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Birth year | 0.00*** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Profile length | 0.03*** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Drinks | 0.12*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing drinks | 0.14*** | 0.03 | ||||||

| 4-year degree (ref.) | ||||||||

| High school | –0.39*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Some college | –0.16*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Postgraduate | 0.10*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing education | 0.17*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Current student | 0.13*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Missing current student | –0.25*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Average body type (ref.) | ||||||||

| Athletic | 0.35*** | 0.01 | ||||||

| Thin | 0.25*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Overweight | –1.14*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Missing body type | –0.29*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| Thresholds | ||||||||

| φ 1 | 1.04*** | 0.01 | 1.04*** | 0.01 | 1.04*** | 0.01 | 1.11*** | 0.01 |

| φ 2 | 2.01*** | 0.01 | 2.02*** | 0.01 | 2.02*** | 0.01 | 2.18*** | 0.01 |

| φ 3 | 3.29*** | 0.01 | 3.29*** | 0.01 | 3.30*** | 0.01 | 3.60*** | 0.01 |

| Level 2 variance | 0.18*** | 0.19*** | 0.17*** | 0.13*** | ||||

Note: Coef. = coefficient; ref. = reference category.

Robust standard errors.

Continuous covariates were centered at their grand means.

Looking first at Model 1, we noted that the likelihood of receiving a message from an attractive sender goes down for receivers with many incoming messages (b = −.002). This is consistent with vertical preferences because the most popular online daters should receive messages from less desirable alters. The negative outgoing message coefficient (b = −.001) also suggested that those who take a “shotgun” approach are likely to receive messages from less desirable daters (thus necessitating a broad search). The female coefficient was large and negative, suggesting that women are more likely than men to receive messages from undesirable alters.

The positive receiver desirability coefficient (b = .533) indicates that messages to more desirable receivers have an increased probability of originating with more desirable alters. An unlisted plot of the cumulative probabilities of male sender desirability across female receiver desirability values was the inverse of Figure 3, with more desirable female daters being more likely than less desirable female daters to receive messages from desirable male senders. The expected desirability gap was greatest for highly desirable female receivers, for whom close to 90% of received messages are predicted to originate from less desirable men.

Among the message-level covariates, the reciprocity indicators show the opposite pattern to those in the receiver-desirability models; increases in reciprocated exchanges raise the odds of interacting with more desirable senders. Increased sender desirability over repeated exchanges may counteract the initially low desirability associated with first contacts and increase desirability homophily over time. To examine this, in Figure 5 we plotted predicted probabilities of sender desirability relative to receiver desirability across the reciprocity categories for average women and men. For female receivers (see Figure 5, Panel A), we noted a high probability (almost 70%) that they are initially contacted by less desirable men, but this probability declines by approximately 20% at the point of first reciprocation. At the same time, the increasing probability of women continuing exchanges with men who are similarly or more desirable than themselves suggests strategic behavior where women choose to continue conversations only with the most desirable men in their pool of suitors. Note, however, that even when the number of exchanged messages reaches the point where prior research suggests an offline date is likely to occur (i.e., more than five exchanged messages), women who are responding to male-initiated messages are more likely connected with men who are less or similarly desirable as themselves. This is in contrast to female-initiated messages, where women have a 60% probability of connecting with more desirable men at the same number of exchanges (see Figure 4, Panel A).

Figure 5.

Predicted Probabilities of Sender Desirability by Reciprocated Exchanges, Average Female (Panel A) and Male (Panel B) Replier.

The average male receiver appears to connect with more desirable partners than does the average female receiver, primarily because men receive messages from more desirable women than vice versa. Therefore, when men increase their selectivity through nonreciprocity, they are likely to connect with more desirable women than themselves. Before recommending a passive strategy for men, we should remember that the likelihood of female-initiated messages are extremely low given that only one in four messages is sent by women and, of these, only 7% are reciprocated more than five times. Even though unlikely, it does appear that men who receive messages and create longer exchanges are able to connect with more desirable women. The initiator advantage thus appears primarily applicable to women.

Model 2 added cross-level interactions between receiver desirability and the reciprocity indicators. The positive and significant coefficients for these interactions suggest that the likelihood of a repeated exchange with a more desirable sender increases with the receiver's desirability. Finally, Models 3 and 4 tested the robustness of our results by including receiver- and sender-level covariates. The message-level coefficients of primary interest were somewhat attenuated, but the overall pattern of results and significance levels remained relatively unchanged, suggesting that the reported effects of (non)reciprocity are robust to measured receiver and sender characteristics..

Discussion

In this study, we used 6 months of data of heterosexual online daters who were active on a metropolitan dating site to test three primary hypotheses for the ways gender, agency, and preferences come together to shape the prospects of a first date. Many of our findings are consistent with prior research, but few studies integrate hypotheses as we did, and the initiator advantage proposition is particularly underrepresented in online dating and assortative mating research.

One hypothesis focused on vertical preferences. Contrary to the matching hypothesis and the observed homophily among married couples, single women and men—at all levels of attractiveness—primarily sought out the most attractive daters as potential partners. For both women and men, the modal category of sent messages, regardless of the senders’ level of attractiveness, was to the highest attractiveness opposite-gender group. As found in earlier research (Berscheid et al., 1971), the tendency to aim for the most desirable partners declined somewhat with one's own desirability, resulting in tempered vertical preferences as one moves down the desirability scale.

Why might daters aim high? We argue that online daters actively aspire to date more socially desirable partners and that these vertical aspirations drive initial requests. This interpretation appears inconsistent with the matching hypothesis, which would predict horizontal preferences. Yet, before throwing out the matching hypothesis, it is important to note that it was originally applied only to realistic choices, whereby individuals make partnering decisions not solely on the basis of individuals’ aspirations, but also on the basis of daters’ perceptions of the probability of success and the negative consequences for failure (Berscheid et al., 1971). The matching hypothesis may then be supported if online dating did not dramatically reduce the potential negative consequences of contacting more desirable partners. In other words, compared to offline dating, online dating solicitations may reflect ideal rather than realistic preferences, and the original matching hypothesis may apply only to the latter (Walster et al., 1966).

This is certainly a possibility and, as we argued at the outset of this article, the reduced fear of rejection increases the appeal of online dating as a means of meeting mates. It is likely that increased access to desirable partners, coupled with low risks of embarrassment, causes online daters to aim higher than they normally would. But even online, daters may temper their fantasies for the sake of eventually achieving a relationship. If the goal is to move the relationship offline, daters with unrealistic aspirations would only be delaying the risks of social rejection. Of course, this might be a risk many are willing to take, suggesting a higher failure rate among online daters who meet in person than daters who originally meet offline. Because we did not know each dater's perceptions or propensity for risk, we could not ascertain whether their partner choices were based on ideal or realistic preferences and thus cannot firmly reject the matching hypothesis. Future research should focus on how ideal goals are tempered by experienced social contexts and the desires of potential partners.

We also found evidence of an initiator advantage in online dating exchanges. Individuals who initiate contact are more likely to pair off with a more desirable partner than those who wait to be asked. It is interesting that the fewer women who initiate contacts do qualitatively better in this online dating market than those who do not.

Although the initiator advantage appears clear in our analyses, the proposed mechanism, perceptual anchoring, may be inadequate. The receiver analyses showed that both female and male daters have no difficulty ignoring requests from less desirable suitors. Indeed, women who receive messages that progress to repeated exchanges connect with men equally as desirable as themselves. For men, these repeated exchanges are with female suitors more desirable than themselves. These patterns do not appear consistent with the idea that daters anchor their preferences to low initial offers. Perhaps a simpler explanation for the initiator advantage is that senders’ repeated attempts to contact more desirable partners sometimes pay off. Only by gambling on the market are initiators able to “get lucky,” though the odds of success are slim even for the most attractive daters.

Our analyses of the initiator advantage provides another example of the ways gender and power come together to shape opposite-sex relationships. Although women are as likely to aim high as men, men are far more likely to initiate online exchanges compared to women. Despite being a new technology used by an educated pool of singles living in a progressive urban area, the differences in how women and men use this technology highlight just how entrenched gendered strategies in intimate relationships remain. Women are still more likely to follow traditional gendered scripts and expect men to initiate relationships (Sassler & Miller, 2011). Although women who initiate and continue conversations are more likely than men to connect with more attractive partners, women are much less likely to seize the initiator advantage. In other words, by relying on men to initiate a relationship, women often forego the promise of online dating and are left wondering where all the good men have gone. Women's inaction can become a means by which gender inequality in intimate relationships is maintained and reproduced (Baldus, 1975; Roscigno, 2011).

An important implication of these findings is that women should not be discouraged from sending messages if they want to contact attractive partners. Of course, the women's sent messages may have primarily been “winks” rather than e-mail messages. The data did not allow us to distinguish these exchanges and, just as in offline dating contexts, online winks may serve as means for women to demonstrate interest with low rejection risk (e.g., “call me maybe”) while letting the man continue to feel like the aggressor.

Our third hypothesis, derived from social exchange theory, related to homophily as a process. We found support for the idea that the population of online couples becomes more homophilous with repeated message exchanges. For both message senders and receivers, the attractiveness gap narrows with increasing message exchanges, particularly at the point of first reciprocation. We would expect this pattern to continue (and perhaps get stronger) as couples move their relationship offline. Our findings suggest that homophily emerges through an interactive social process. Individuals may begin their search by seeking out that “one in a million” partner, but surviving couples tend to be more similar in their levels of social desirability.

Considered collectively, these findings provide important insights into the earliest stages of relationship formation. By observing actual search behavior instead of asking daters their partner preferences, unrecognized prejudices and desires were removed, and we captured preferences through actual choices. Moreover, by following dyads through time, we gained insights into the earliest stages of relationship progression and emerging homophily. These findings comport well with the developing interdisciplinary literature on online dating. Online dating is becoming an increasingly common means by which couples meet (Rosenfeld & Thomas, 2012). Like Hitsch and colleagues (2010a, 2010b), we found that preferences related to attractiveness are vertical, with both women and men seeking more attractive partners. But rather than pit vertical preferences (i.e., attractiveness) against horizontal (i.e., age, race, education) preferences, we argue that our findings isolate a meta-level preference for more socially desirable partners that do not preclude homophilous preferences for specific characteristics, such as smoking, music, race, religion, and so on. In other words, vertical preferences are likely to operate conditionally on a person's specific tastes, nonnegotiable partner traits, and contextual constraints. They may also operate conditionally on individuals’ motivations for a relationship or their age. What we have identified is a global pattern that is likely shaped by meso- and micro-level contexts. We hope to explore these moderating contexts and subgroup processes in future research.

Important limitations remain. The most significant is that we could not observe relationship outcomes. Our observation of multiple exchanges gives us some clue as to an eventual date, but without message content or follow-up interviews, it remains possible that few of these exchanges resulted in face-to-face meetings. Although the absence of relationship outcomes might be considered a strong limitation, we argue that our data have the important benefit of illuminating a process that is typically invisible. The pairing and sequencing of initial message exchanges was previously accessible only through direct observation or retrospective surveys. We were able to observe these exchanges and measure their dyadic properties. Moreover, the hypotheses that we advanced were specifically directed at these initial stages.

By including a message-level variable for the temporal ordering of messages within each dater's message history, we were able to gain leverage on the possibility that online daters change their preferences on the basis of their online experiences. In other words, online partner preferences may be endogenous and updated given changing information (Becker, 1996). We found little evidence for such updating in the aggregate. The ordering of senders’ messages had a nonsignificant association with the attractiveness of the daters who received the messages. However, because this was not our primary focus, we did not conduct a detailed analysis of within-person preference change. In future analyses, we intend to focus on the temporality of sent and received messages and test whether daters adjust their preferences, outgoing activity, and reciprocated exchanges on the basis of prior online experiences.

Future research should also test whether vertical preferences apply to other social contexts and relationships. We were careful to confine our findings to one dating market at one point in time, but we expect similar processes are functioning in other contexts and social networks. It is axiomatic to sociological theory that individual preferences and tastes are shaped by their social contexts (Bourdieu, 1984). Local marriage and dating markets, commonly operationalized by economic conditions or the ratio of marriageable men to women, are argued to explain differential marriage patterns, to shape partner preferences, and to establish the minimum “quality” partner that one will accept (Harknett & McLanahan, 2004; Lichter, LeClere, & McLaughlin, 1991). Thus, in a weak market, an attractive woman may be unable to attract a high-quality partner and thus may have lower standards than expected. Conversely, in a strong market, an individual may have higher than average standards for a potential partner. In other words, preferences reflect, in part, “the adjustment of people's aspirations to feasible possibilities” (Elster, 1982, p. 219). By exploring vertical preferences and the initiator advantage in other online dating markets, researchers can begin to determine the role of social context in shaping relationship behaviors.

Our data did not permit us to explore same-sex online dating networks, which may show a pattern of results different from those observed above. Rosenfeld and Thomas (2012) demonstrated that online dating is extremely influential among singles searching for same-sex partners. For example, in their nationally representative survey, 61% of same-sex couples who met between 2007 and 2009 met online, a rate over three times higher than opposite-sex couples who met the same way. Future research should test whether vertical preferences and initiator advantages operate in these online dating markets.

We also did not have access to two measures that are potentially important for online daters’ messaging and decision making: (a) profile creation and termination dates and (b) “matching scores” derived from the dating site's computer algorithm. Although omitting these measures may have biased our presented estimates, they are also extremely difficult to operationalize and/or interpret even if they are available. For example, because there are no membership dues for the dating site we used, online daters are never forced to remove their profiles, even if they have been inactive for an extended period. Similarly, profile creation requires minimal information that can be added to, or not, over time. These dynamics complicate the operationalization of “time online.” With regard to matching scores, their ever-changing calculation and the complexity of the algorithms underlying them complicate their use. We thus leave it to future research to delve into such constructs and ascertain their impact on gender and messaging behavior.

A final limitation relates to the potential for rater bias in our social desirability measure. Although the large number of ratings (almost 2 million evaluations for our sample) increases the measure's reliability, the rater characteristics are unknown and may not represent the online dating population. It is comforting that the correlates of our desirability measure are similar to those of prior research. We cannot, however, rule out the possibility that the desirability measure does not reflect the majority of daters’ preferences, even in this specific dating market. Future research should test the generalizability of similar desirability ratings and potential differences across time, place, or online dating site.

We began this article arguing that online dating removes many of the structural barriers and social sanctions that constrain offline dating. This makes online dating an ideal domain for examining partner preferences and the initial dating contacts based on those preferences. This same logic, however, suggests that offline singles often lack the opportunities to meet desirable partners, or are inhibited by perceived social sanctions. In real-world contexts, dating may then appear to be based on homophilous preferences because vertical preferences are constrained and only stable couples are observed. This also implies that many daters enter relationships with partners whom, given unlimited options, they do not prefer. As with many decisions, social constraints and the actions of others force daters to lower their aspirations and satisfice rather than maximize. The dissonance between idealized and realized partnerships may be a destabilizing force in relationships over time, or dissipate as commitment increases and partnerships progress. It remains for future research to assess whether individuals who satisficed at a relationship's outset perceive the grass as greener on the other side, or if the satisfactions of the relationship outweigh any temptation to “trade up.”

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grants from the W. T. Grant Foundation (8316) and DTRA (1-09-1-0054), awarded to Derek A. Kreager. This research was also supported by Grant 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We thank Rich Felson, Wayne Osgood, and Jennifer Glass for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

REFERENCES

- Back MD, Penke L, Schmukle SC, Sachse K, Borkenau K, Asendorpf JB. Why mate choices are not as reciprocal as we assume: The role of personality, flirting and physical attractiveness. European Journal of Personality. 2011;25:120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Baldus B. The study of power: Suggestions for an alternative. Canadian Journal of Sociology. 1975;1:179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Accounting for tastes. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Dion K, Walster E, Walster GW. Physical attractiveness and dating choice: A test of the matching hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1971;7:173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100:1261–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Curran JP, Lippold S. The effects of physical attraction and attitude similarity on attraction in dating dyads. Journal of Personality. 1975;43:528–539. [Google Scholar]

- Elster J. Sour grapes—Utilitarianism and the genesis of wants. In: Sen A, Williams B, editors. Utilitarianism and beyond. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1982. pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- England P. More mercenary mate selection? Comment on Sweeney and Cancian. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:1034–1037. [Google Scholar]