Abstract

Neurons in the enteric nervous system utilize numerous neurotransmitters to orchestrate rhythmic gut smooth muscle contractions. We examined whether electrical synapses formed by gap junctions containing connexin36 also contribute to communication between enteric neurons in mouse colon. Spontaneous contractility properties and responses to electrical field stimulation and cholinergic agonist were altered in gut from connexin36 knockout vs. wild-type mice. Immunofluorescence revealed punctate labelling of connexin36 that was localized at appositions between somata of enteric neurons immunopositive for the enzyme nitric oxide synthase. There is indication for a possible functional role of gap junctions between inhibitory nitrergic enteric neurons.

Keywords: gastrointestinal system, nitric oxide, nitric oxide synthase, immunofluorescence, EGFP reporter, connexin36 knockout

1. Introduction

The enteric nervous system (ENS) plays a major role in the regulation of gastrointestinal homeostasis. Enteric neurons in both the myenteric plexus and submucosal plexus contain a plethora of classical and peptide neurotransmitters, with often several present in the same neuron, that have been used to classify subpopulations of neurons according to their transmitter content, anatomical organization and contributions to microcircuitry governing gut contractile activity [1,2]. Among the multiple transmitters in individual excitatory or inhibitory enteric neurons, some have primary roles in neural control of gut smooth muscle contraction, relaxation, sensory feedback and reflex activity [3]. Contraction is mainly driven by neurons that release tachykinins and acetylcholine, while relaxation results form activation of non-adrenergic and non-cholinergic neurons, including those that release vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, ATP and nitric oxide (NO). In addition, gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) channels connect smooth muscle cells and interstitial cells of Cajal in various configurations, and thereby spread pacemaker and contractile signals regulated by enteric neurons [4-6]. Among the twenty or so connexin proteins (designated Cx followed by MW) that form gap junctions, creating pores that allow intercellular passage of ions and small molecules between cells [7], those expressed in the deep muscular and submuscular plexuses of the intestinal system include Cx40, 43 and 45 [8-12]. Studies involving the use of gap junction blockers and mice with ablation of Cx43 have indicated a functional contribution of GJIC provided by these connexins to patterns of intestinal smooth muscle activity [13-15].

Recently, Frinchi et al.[16] reported expression of connexin36 (Cx36) in an as yet undetermined cell type in mouse ileum and colon, and noted “that it has been known for a long time that the myenteric plexus can mediate neural activity in the gastrointestinal musculature through interneuronal communication by gap junctions”, implying Cx36 localization to neuronal gap junctions in gut. To our knowledge and contrary to their statement, gap junctions between neurons in the ENS have not been described. Nevertheless, based on studies of Cx36 in the CNS, their observation raised the possibility of a contribution of this connexin to GJIC between enteric neurons. In the CNS, it is well established that Cx36 is widely expressed in a variety of neuron types, often though not always in inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) neurons [17-19], and forms gap junctions that are the structural substrate of electrical synapses [20]. Electrical synapses in the CNS confer synchronous neuronal activity by linking electrical oscillations among ensembles of gap junctionally coupled neurons, and thus temporally correlate firing patterns in otherwise disparate networks[19]. It is widely considered that synchronous neuronal activity in the CNS underlies a broad range of information processing. These points, supported by studies of Cx36 knockout (ko) mice [17,19], indicate indispensable roles of electrical synapses in neural network properties in the CNS.

The formation of electrical synapses in the ENS could be equally important in orchestrating the activity of enteric neurons in their control of complex patterns of gut contractility. In the present study, we conducted immunofluorescence analyses of Cx36 in combination with neuronal markers, focusing specifically on inhibitory neurons that express neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). In addition, we examined EGFP reporter expression in the ENS of transgenic mice in which this reporter is driven by the Cx36 promoter. Further, we used in vitro organ bath chambers to investigate contractility parameters of gut from wild-type vs. Cx36 ko mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The present studies involved the use of three Sprague-Dawley adult rats, and a total of eighteen mice of the C57BL/6-129SvEv strain with a targeted disruption of the Cx36 gene (Cx36(−/−)) and their Cx36(+/+) wild-type (WT) littermates, and four mice in which Cx36 expression is normal and bacterial artificial chromosome provides EGFP expression driven by the Cx36 promoter, designated EGFP-Cx36 mice. Colonies of the C57BL/6-129SvEv wild-type and Cx36 ko mice [21] were established at the University of Manitoba through generous provision of breeding pairs of these mice from Dr. David Paul (Harvard). The EGFP-Cx36 mice were taken from a colony of these mice maintained at the University of Manitoba and originally obtained from UC Davis Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (designated Tg(Gjd2-EGFP)16Gsat/Mmcd Cx36 EGFP mice; strain FVB/N-Crl:CD1(ICR) hybrid; Davis, CA, USA (see also http://www.gensat.org/index.html). The mice were matched for age, body weight (22–25 g), and allowed ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow and water. All mice were maintained in a double barrier unit in a room that had controlled temperature (21 ± 2 °C), humidity (65%–75%), and light cycle (12 h light/12 h dark). All animals were used in accordance to protocols approved by the Central Animal Care Committee of the University of Manitoba (10-073 and 10-431).

2.2. In vitro analyses of smooth muscle contraction

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and segments of distal colon were removed, submerged in ice-cold oxygenated Krebs solution (120 mM NaCl, 1.4 mM NaH2PO4, 15 mM NaHCO3, 5.8 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 11 mM glucose). Preparations were gently flushed to remove luminal contents. A total of 10 mice were taken to generate twenty colonic strips. Segments of colon, 1 cm in length, were ligated at each end with silk thread and suspended longitudinally in each of up to eight chambers of 15 ml isolated organ baths (Panlab Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Massachusetts, USA), containing Krebs solution maintained at 37 °C and aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2. These preparations were positioned between a pair of parallel platinum electrodes, separated by 1.4 cm, and attached to an isometric force transducer (MLT0201 AD Instruments, Dunedin, New Zealand). Spontaneous smooth muscle activity (SMA) and responses to electrical field stimulation (EFS) were measured in isometric conditions. The mechanical activity of the muscle was measured using a transducer amplifier relayed to a bioelectric amplifier (ML228, AD Instrument) equipped to record muscle contractions via a data acquisition system (PowerLab16/30, ADinstrument, CO, USA). At the beginning of each experiment, muscle strips were stretched to their optimal resting tone. This was achieved by step-wise increases in tension until the contractile responses between two EFS were maximum and reached stable amplitude. The target stretching set point was 9 millinewton (mN), and a 15 min equilibration time was incorporated between every stretch. Typically, muscle strips were stretched to 180 ± 15% of their initial length. SMA was characterized fifteen minutes after the last EFS followed by a bath solution change, and included measurements of tone as well as amplitude and frequency of spontaneous contractions over three one-minute periods. To examine muscle contractility response to EFS, colonic preparations were subjected to EFS with the following parameters; monophasic train with train duration of 10 seconds, pulse rate of 16 pulses per second, pulse duration of 0.5 ms, pulse delay of zero seconds, and a voltage of 24 volts (Grass S88X, Grass Technologies, Natus Neurology, Middleton, WI, USA). EFS parameters were chosen by modifying the frequency and voltage to obtain maximal relaxation and C-off for a 9 mN tension. Different values of voltage (5 V, 10 V, 15 V and 24 V), and frequencies (5, 10, 16 HZ), and the optimal combination was chosen. Contractility response values are presented as the average of three repetitions of the EFS-generated contractility response. At the end of the applied EFS, and after two bath solution changes (10 min interval), contractile responses to cholinergic stimulation were assessed by exposure to three doses of carbachol. Gut segments were exposed to non-cumulative final bath concentrations of 1, 10 and 100 μM carbachol by addition of microliter aliquots to 15 ml tissue baths. After the maximal tone response to each dose was obtained (5 mins), tissues were rinsed twice and equilibrated in fresh Krebs solution for 15 min before addition of the next agonist dose. Increased tone was calculated from the mean basal tone and maximal point of response.

The force generated by spontaneous SMA, responses to EFS and dose-response to carbachol are expressed in mN and normalized for cross-sectional area as determined by the following equation: cross-sectional area (mm2) = tissue wet weight (mg)/[tissue length (mm) × density (mg/mm3)], where density of smooth muscle was defined to be 1.05 mg/mm3 [22]. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, and differences between groups were evaluated using a Student’s t-test for unpaired data. Difference were considered significant at p < 0.05.

2.3 Immunofluorescence procedures

Tissues taken for immunofluorescence labelling were prepared by transcardiac perfusion with a series of solutions. Adult mice and rats were euthanized with an overdose of equithesin (3 ml/kg), placed on a bed of ice, and perfused first with cold (4°C) pre-fixative (20 ml per 100 g body weight) consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.1% sodium nitrite, 0.9% NaCl and 1 unit/ml of heparin. For experiments involving immunohistochemical detection of Cx36, animals were then perfused with fixative solution containing cold 0.16 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.2% picric acid and either 1% or 2% formaldehyde diluted from a 20% stock solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). The perfusate volumes were 50-100 ml per 100 g body weight. For experiments involving immunohistochemical detection of EGFP, mice were perfused with fixative solution containing cold 0.16 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.2% picric acid and 4% formaldehyde. The fixative perfusion was followed by perfusion of animals with a solution containing 10% sucrose and 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, to wash out excess fixative. Duodenum, jejunum, ileum and colon were removed and stored at 4°C for 24-48 h in cryoprotectant containing 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 10% sucrose, 0.04% sodium azide. Transverse or horizontal sections of gut were cut at a thickness of 10-15 μm using a cryostat and collected on gelatinized glass slides. Slide-mounted sections were stored at -35 ° until use.

Immunofluorescence labelling was conducted with primary antibodies used in various combinations. Anti-Cx36 antibodies were obtained from Life Technologies Corporation (Grand Island, NY, USA) (formerly Invitrogen/Zymed Laboratories), and those used included two rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Cat. No. 36-4600 and Cat. No. 51-6300) and one mouse monoclonal antibody (Cat. No. 39-4200). These anti-Cx36 antibodies were incubated with tissue sections at a concentration of 1-2 μg/ml. Monoclonal anti-EGFP developed in rabbit or polyclonal anti-EGFP developed in chicken were obtained from Life Technologies Corporation and Aves Labs Inc. (Tigard, Oregon, USA), respectively, and used at a concentration of 1-2 μg/ml. Polyclonal antibodies against nNOS developed in rabbit or goat were obtained from Cell Signalling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) and Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA) and used at a dilution of 1:200 and 1:250, respectively. Anti-dynorphin A antibody developed in rabbit was obtained from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc (Burlingame, CA, USA) and used at a dilution of 1:200. Additional antibodies used against neuronal markers included antibodies against NeuN developed in guinea pig and diluted 1:250 (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA), tryptophan hydroxylase developed in sheep and diluted 1:500 (Millipore), calcitonin gene related peptide developed in goat and diluted 1:2000 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and substance P developed in guinea pig and diluted 1:1000 (Novus Biologicals). Various secondary antibodies used included Cy3-conjugated goat or donkey anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1:600, Cy5-conjugated anti-guinea pig IgG diluted 1:600 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), AlexaFluor 488-conjugated goat or donkey anti-rabbit, anti-mouse and anti-guinea pig IgG used at a dilution of 1:600 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), and AlexaFluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG used at a dilution of 1:600 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). All primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1.5% sodium chloride (TBS), 0.3% Triton X-100 (TBSTr) and 10% normal goat or normal donkey serum.

Slide mounted sections were removed from storage, air dried for 10 min, washed for 20 min in TBSTr, and processed for immunofluorescence staining, as previously described [23-25]. For double or triple immunolabelling, sections were incubated simultaneously with two or three primary antibodies for 24 h at 4°C. The sections were then washed for 1 h in TBSTr and incubated with appropriate combinations of secondary antibodies for 1.5 h at room temperature. Some sections processed for double immunolabelling were counterstained with Blue Nissl fluorescent NeuroTrace (stain N21479) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Sections were coverslipped with the antifade medium Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AB, USA). Control procedures involving omission of one of the primary antibodies with inclusion of the secondary antibodies used for double labelling indicated absence of inappropriate cross-reactions between primary and secondary antibodies.

Immunofluorescence was examined on a Zeiss Axioskop2 fluorescence microscope and a Zeiss 710 laser scanning confocal microscope, using Axiovision 3.0 software or Zeiss ZEN Black 2010 image capture and analysis software (Carl Zeiss Canada, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Data from wide-field and confocal microscopes were collected either as single scan images or z-stack images with multiple optical scans at z scanning intervals of 0.4 to 0.6 μm. Images of immunolabelling obtained with Cy5 fluorochrome were pseudo colored blue. Final images were assembled using CorelDraw Graphics (Corel Corp., Ottawa, Canada) and Adobe Photoshop CS software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Immunofluorescence of Cx36 in mouse gut

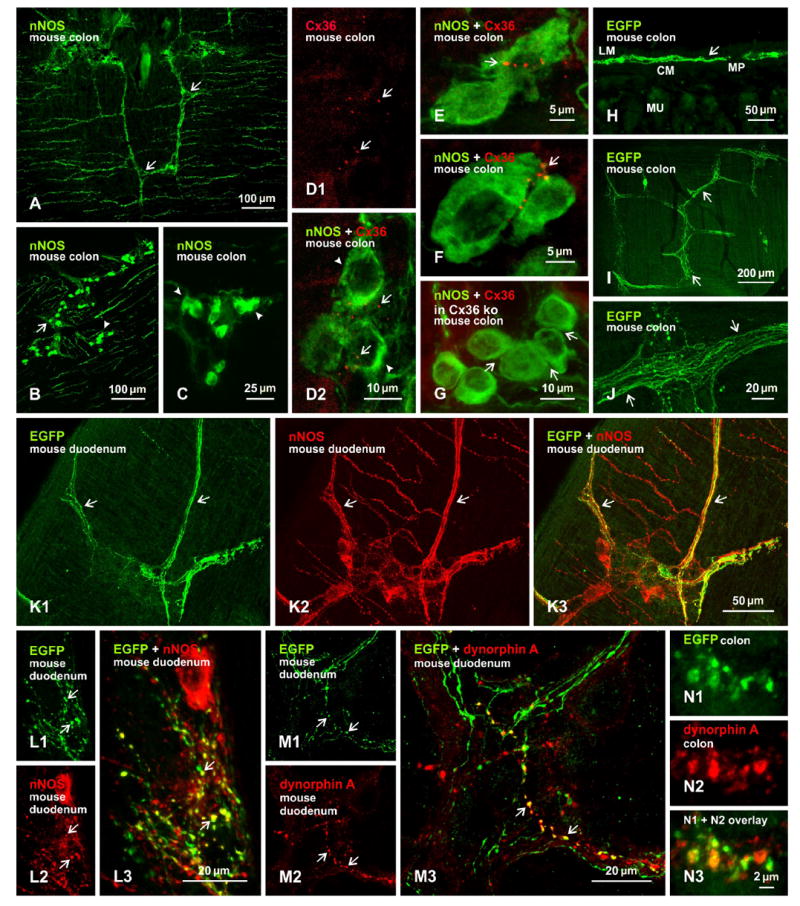

In the CNS, electrical synapses formed by gap junctions containing Cx36 often, though not always, occur between inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) neurons [18,19]. In view of this, together with our observations suggesting an impairment of inhibitory neuronal control of gut contractility in Cx36 ko mice (described below), we examined immunofluorescence labelling of Cx36 in relation to a broad class of inhibitory enteric neurons, consisting of many if not all that express nNOS in subclasses distinguished by their expression of different neuroactive peptides or other markers [2]. Immunofluorescence labelling for nNOS in gut was remarkably robust with the antibodies we used, revealing intense labelling for this enzyme in tissues prepared both with the weak fixation conditions required for immunolabelling of Cx36 and the stronger fixation required for detection of EGFP. Dense bundles of nNOS-positive fibers were routinely observed in rat and mouse myenteric plexus, as shown in mouse (Fig. 1A), and ganglionic clusters of nNOS-positive neuronal cell bodies were also readily visualized, although their initial and extended dendritic processes were less evident (Fig. 1B,C). Perhaps relevant, based on observations below, is that these cell bodies tended to be distributed in two patterns; either scattered with clear separation between them (Fig. 1B), or closely clustered with apparent apposition of their somata (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence labelling of nNOS, Cx36, EGFP reporter in EGFP-Cx36 mice and dynorphin A in myenteric plexus of adult mouse colon. A-C: Labelling of nNOS is localized to fiber bundles (A, arrows) and clusters of neuronal cell bodies (B, arrows and arrowheads) distributed in the myenteric plexus, and the somata of nNOS-positive cells within these clusters are either scattered (B, arrows) or are closely apposed (B, arrowheads; magnified in C, arrowheads). D: Punctate appearance of labelling for Cx36 in the myenteric plexus (D1, arrows), and overlay of the same field with labelling for nNOS, showing Cx36-puncta (D2, arrows) distributed among nNOS-positive neurons (D2, arrowheads). E-F: Higher magnifications showing Cx36-puncta at appositions between nNOS-positive neuronal somata in proximal (E, arrow) and distal (F, arrow) colon, and absence of labelling for Cx36 at appositions between nNOS-positive somata (G, arrows) in myenteric plexus of Cx36 ko mice. H-J: Immunofluorescence labelling of EGFP in colon, showing EGFP localized to the myenteric plexus in transverse section (H, arrow), and bundles of intensely labelled fibers in horizontal sections (I, arrows; magnified in J, arrows). K, L: Images of the same field (K1-K3) showing fibers labelled for EGFP (K1, arrows) and nNOS (K2, arrows), with EGFP/nNOS co-distribution seen as yellow in overlay (K3, arrows), and higher magnification (L) showing EGFP/nNOS co-localization at nerve terminals and along varicose fibers (arrows). M: Three images of the same field, showing varicosities along fibers labelled for EGFP (M1, arrows) and dynorphin A (M2, arrows), and EGFP/dynorphin A co-localization seen as yellow (M3, arrows; magnified in a region of colon in N). Abbreviations in H: MP, myenteric plexus; CM, circular muscle layer; MU mucosal layer; LM, longitudinal muscle layer.

Immunofluorescence labelling of Cx36 was detected in adult mouse gut, as expected based on a previous report of Cx36 expression in this tissue [16]. As in all areas of the CNS that we and other [24-29] have examined, labelling had an exclusively punctate appearance, which we refer to as Cx36-puncta (Fig. 1D1). Although not comprehensively examined throughout the intestinal system, these puncta were observed in duodenum, jejunum and ileum, but in mouse were most evident in the colon, where they were restricted to the myenteric plexus. In sections of colon double-labelled for Cx36 and nNOS, Cx36-puncta were frequently seen in the vicinity of, and in intimate association with, nNOS-immunopositive neurons (Fig. 1D2). Often, Cx36-puncta occurred among clustered nNOS-positive neurons, and particularly at sites where these neurons came into close apposition and where multiple puncta were linearly arranged along the appositions, as shown in proximal (Fig. 1E) and distal (Fig. 1F) colon. In sections immunostained for both Cx36 and nNOS, and counterstained with fluorescence blue Nissl stain, examination of hundreds of nNOS-positive somata bearing Cx36-puncta revealed only three examples where these puncta appeared to be lying between a nNOS-positive and a nNOS-negative somata (Fig. S1). Immunolabelling of Cx36 in combination with the neuronal marker NeuN also showed association of Cx36 with a subpopulation of neuronal somata immunolabelled for NeuN (not shown).

Confocal through focus analysis in the z-axis indicated that Cx36-puncta did not occur intracellularly, but rather were distributed along the periphery of neurons. Scattered nNOS-positive cells rarely displayed Cx36-puncta. In sections of colon from Cx36 ko mice, Cx36-puncta were absent among clusters of nNOS-positive cells, and at appositions between these cells (Fig. 1G). It is of note that while Cx36-puncta in wild-type mice were routinely encountered, they were not observed in association with all clustered neurons labelled for nNOS. Although it might therefore be considered that the single image presented in Figure 1G is less informative, it is nevertheless representative of at least a dozen five by five mm horizontal sections of gut from Cx36 ko mice in which no Cx36-puncta were seen in the myenteric plexus. In considering results from Cx36 ko mice, it is also of note that the intensity of diffuse intracellular fluorescence was not distinguishably different in nNOS-positive cells of wild-type vs. Cx36 ko mice, indicating absence of detectable intracellular labelling for Cx36, perhaps due to blockade of antibody epitope on Cx36 or rapid trafficking of Cx36 to the plasma membrane leaving low cytoplasmic levels.

3.2. EGFP reporter in EGFP-Cx36 mice

In EGFP-Cx36 mice, immunofluorescence labelling for EGFP was abundant in the duodenum, jejunum and ileum, and was localized to the myenteric plexus, as shown in a transverse section of the colon (Fig. 1H). In horizontal sections, labelling for EGFP was localized to bundles of fibers (Fig. 1I) as well as at terminals and along varicosities of these fibers (Fig. 1J). Unfortunately, two factors precluded analysis of labelling for EGFP in relation to Cx36. First, neuronal cell bodies, where Cx36 were localized, were never immunopositive for EGFP, perhaps due to its rapid export from neuronal cytoplasm or inadequate fixation of EGFP localized in the cytoplasm of neuronal somata. Second, the strong fixation (4% formaldehyde) required for detection of EGFP obliterated labelling of Cx36, which required weak fixation (1% formaldehyde). Nevertheless, EGFP reporter expression in the myenteric plexus of EGFP-Cx36 mice is consistent with Cx36 expression and immunofluorescence detection in this plexus.

Given the localization of Cx36 to a subpopulation of nNOS-positive enteric neurons, we next sought to determine the correspondence of EGFP expression in EGFP-Cx36 mice to that of nNOS in these mice. In double-labelled horizontal sections of duodenum (Fig. 1K), labelling for EGFP among fiber bundles (Fig. 1K1) is seen widely co-distributed with those labelled for nNOS (Fig. 1K2). However, sets of fibers immunopositive for nNOS were clearly devoid of labelling for EGFP (Fig. 1K3). Detailed inspection revealed localization of EGFP at nerve terminals and along axonal varicosities of many but not all nNOS-positive fibers (Fig. 1L), again consistent with Cx36 expression in a subclass of nNOS-containing enteric neurons. Conversely, only a very few EGFP-positive fibers and terminals lacked labelling for nNOS. Among the repertoire of different neurotransmitter markers expressed in various subclasses of enteric neurons that express nNOS, only one of those in the myenteric plexus also contain dynorphin A (1). Double immunofluorescence labelling revealed co-localization of EGFP with some but not all dynorphin-positive fibers and terminals. Conversely, dynorphin was co-localized with some but not all EGFP-positive fibers and terminals, indicating expression of EGFP reporter for Cx36 in a subpopulation of nNOS/dynorphin-containing enteric neurons (Fig. 1M, N). Despite adequate labelling of dynorphin along terminals and fibers under the range of fixation conditions we used, neuronal somata were not sufficiently labelled to allow determination of Cx36-puncta localization to dynorphin-positive somata.

Expression of EGFP was also examined in relation to enteric neuronal elements containing tryptophan hydroxylase, calcitonin gene related peptide and substance P in colonic tissue of EGFP-Cx36 mice. Fibers, nerve terminals and axonal varicosities immunopositive for EGFP lacked overlap with those immunolabelled for these other neuronal markers (not shown).

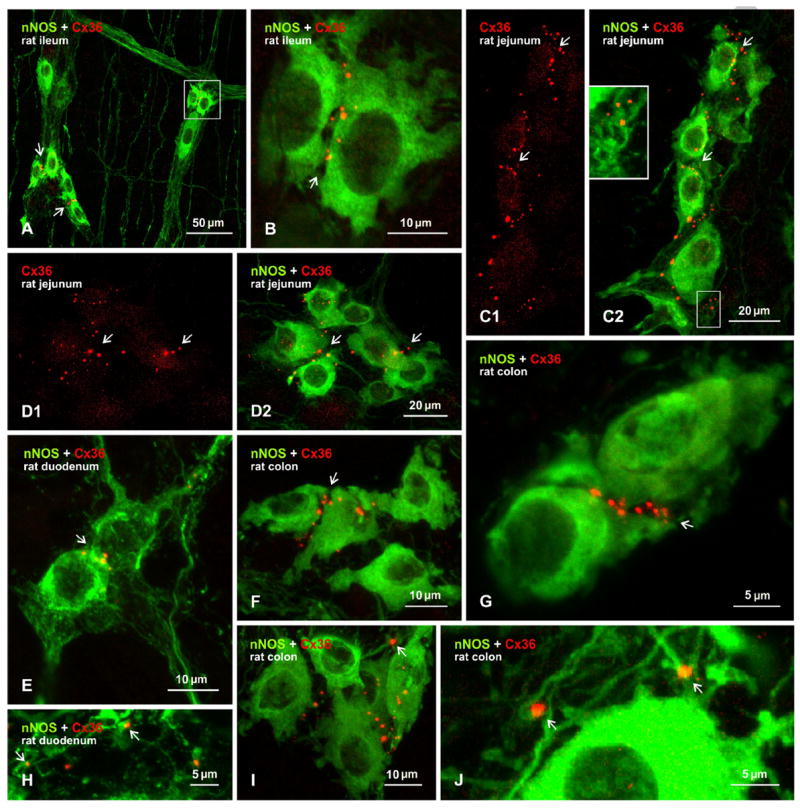

3.3. Immunofluorescence of Cx36 in rat gut

Results on relationships between Cx36-puncta and nNOS-containing enteric neurons in rat gut were in general similar to those found in mouse (Fig. 1). However, Cx36-puncta tended to be more numerous and were of greater fluorescent intensity than in mouse. Although sections at short intervals along the entire intestinal length were not systematically examined, Cx36-puncta were consistently seen in association with nNOS-positive neuronal cell bodies in the myenteric plexus of randomly selected tissue segments from the ileum (Fig. 2A,B), jejunum (Fig. 2C,D), duodenum (Fig. 2E) and colon (Fig. 2F,G). In samples of gut taken for counts of Cx36-puncta in each segment of gut (i.e., duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon) by wide-field microscopy, all of a cumulative total of 1,759 puncta counted were associated with, or lying in close proximity to, a cumulative total of 499 nNOS-positive somata. While this yields an average of 3.5 Cx36-puncta per somata, through focus microscopy will be required to obtain a more accurate average. As in mouse, Cx36-puncta were distributed around the periphery of nNOS-containing cells, including at appositions between these cells (e.g., Fig. 2B, C, F, G). Very rarely, Cx36-puncta were seen overlying nNOS-positive somata as in some of the images presented (Fig. 2F, I), but all of these images were z-stacks of 3-7 μm confocal scans, and through focus analysis indicated those puncta to be localized to neuronal surfaces. Immunolabelling for nNOS along what appeared to be initial dendritic segments was only marginally more evident in rat than mouse, but this nevertheless revealed some Cx36-puncta localized to these processes (Fig. 2C, H-J), including sites of intersection between these process (Fig. 2I, J). In cases of sections from rat where Cx36-puncta were seen in close vicinity but not at the surface of nNOS-positive somata, high confocal magnifications with increased photomultiplier gain settings invariably revealed association of these puncta with nNOS-positive processes (Fig. 2C2, inset). Immunolabelling of dynorphin A in sections of rat gut was not of sufficient quality to allow determination of whether Cx36-puncta were associated with a subclass of nNOS-containing neurons that express dynorphin A.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence labelling of Cx36 associated with nNOS-positive neurons in sections of the myenteric plexus in various regions of gut from adult rat. A, B: Immunolabelling overlay image from ileum, showing Cx36-puncta associated with clusters of nNOS-positive neuronal somata (A, arrows) and at appositions between these somata, as seen in boxed area in (A) shown magnified in (B, arrow). C-D: Transverse (C) and horizontal (D) sections of jejunum showing labelling for Cx36 alone (C1, D1, arrows) and association of Cx36-puncta with nNOS-positive neurons in overlay (C2, D2, arrows). Inset in C2 is a magnification of the boxed area, with intensified green fluorochrome, showing Cx36-puncta association with nNOS-positive processes. E-G: Overlay images showing Cx36-puncta localized around neurons labelled for nNOS in duodenum (E, arrows) and colon (F, arrow), with colon shown at higher magnification in (G, arrows). H-J: Overlay images showing Cx36 associated with nNOS-positive processes in duodenum (H, arrows) and colon (I, arrow), and at sites of crossing fibers in colon (J, arrow).

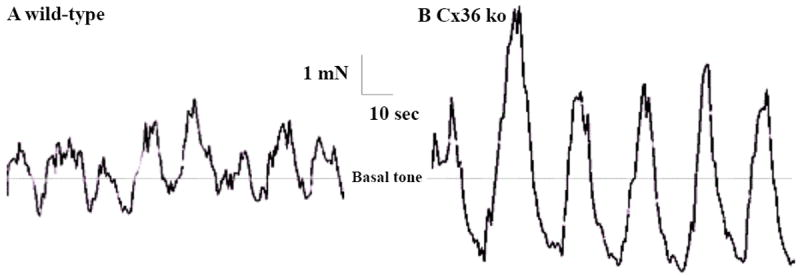

3.4. Spontaneous mechanical activity

Both excitatory and inhibitory enteric neurons control the activity of gut smooth muscle, including the rhythmic spontaneous contractile activity that is readily observable in organ bath preparations in vitro. As we found a close relationship between Cx36-puncta and nNOS-containing enteric neurons in mouse and rat gut, we next investigated whether the lack of Cx36 in Cx36 ko mice was accompanied by alterations in gut smooth muscle motor behaviour, using colonic smooth muscle strips and focusing first on spontaneous activity. In gut from WT mice examined under isometric conditions (Fig. 3A), longitudinal colonic muscle strips developed spontaneous SMA characterized by the occurrence of phasic contractions having an amplitude of 1.55 ± 0.35 mN/mm2, a frequency of 6.5 ± 1.1 cycles/per min and a basal tone of 8.8 ± 0.8 mN/mm2 (Fig. 3A). As shown in Figure 3B and Table 1, the amplitude of the spontaneous phasic contractions was significantly increased by 3.1-fold in colonic strips from Cx36 ko mice. As might be expected from the addition of this large change in amplitude to the time required to reach maximum contraction and relaxation, the frequency of contractions was reduced by about 18% in gut from Cx36 ko vs. WT (Fig. 3, Table 1), but this value failed to reach significance. The basal tone, derived from an average of the integrated areas within the peaks of contraction and relaxation, was not different in gut from WT vs. Cx36 ko mice (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Spontaneous SMA in organ bath preparations of colonic muscle strips from adult WT and Cx36 ko mice. A: Spontaneous SMA is characterized by rhythmic and phasic contractions in colonic strips from WT mice (A). B: A significant increase in amplitude is seen in strips from Cx36 ko mice. The frequency of the contractions was decreased, though non-significantly in strips from Cx36 ko gut. Dashed line represents similar WT vs. Cx36 ko mean basal tone (expressed as mN) generated by the colonic muscle strips under isometric conditions and do not reflect the integrations of cross-sectional area.

Table 1.

Parameters of spontaneous SMA developed by colonic longitudinal smooth muscle strips from WT and Cx36 ko mice.

| Parameters | wild-type | Cx 36 ko |

|---|---|---|

| Amplitude (mN/mm2) | 1.55 ± 0.35 | 4.8 ± 0.67* |

| Basal tone (mN/mm2) | 8.8 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 0.9 |

| Frequency (cpm) | 6.5 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.41 |

Amplitudes and basal tone are expressed as mN per muscle cross-sectional area (mm2). Basal tone represents the mean tone generated by colonic strips under isometric conditions after final equilibration and served as a reference for amplitude calculation. Frequency is expressed as contractions per minute (cpm). Asterisk indicates significant difference between WT vs. Cx36 ko. Values are means + and SEMs, unpaired t-test,

p < 0.05, n = 20.

Stretching functionality, defined as the length of tissue for a fixed assigned basal tone and measured after equilibration and determination of optimal load, was not affected; the average length of colonic strips from WT mice was 12.6 ± 0.9 mm, whereas that from Cx36 ko mice was 10.6 ± 0.9 mm). Moreover, tissue-wet weight (measured immediately after completion of contractility measurements) and cross-sectional area from both genotypes were similar (WT and ko, 12.7 ± 0.9 mg vs. 11.2 ± 0.7 mg; and 0.58 ± 0.04 vs. 0.61 ± 0.08 mm2, respectively), thus excluding tissue sample density as a factor contributing to differences in the contractile properties of WT vs. Cx36 ko colonic strips.

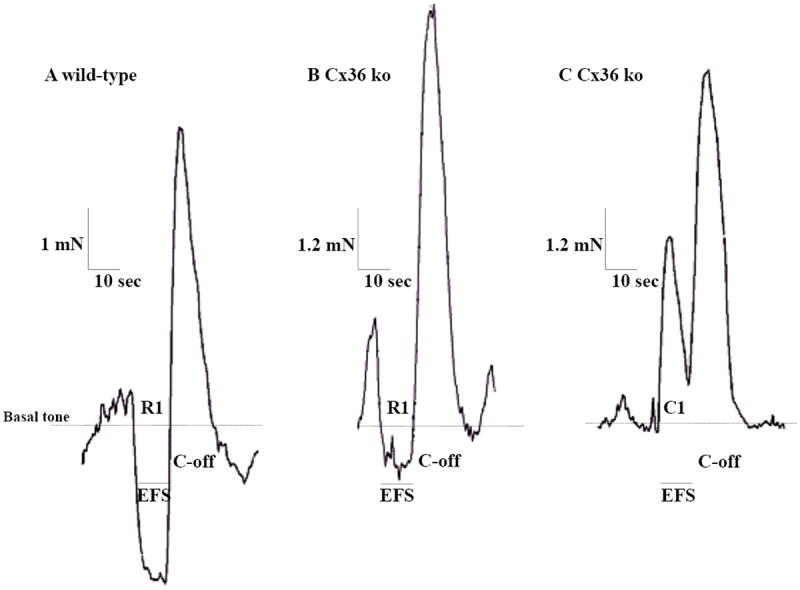

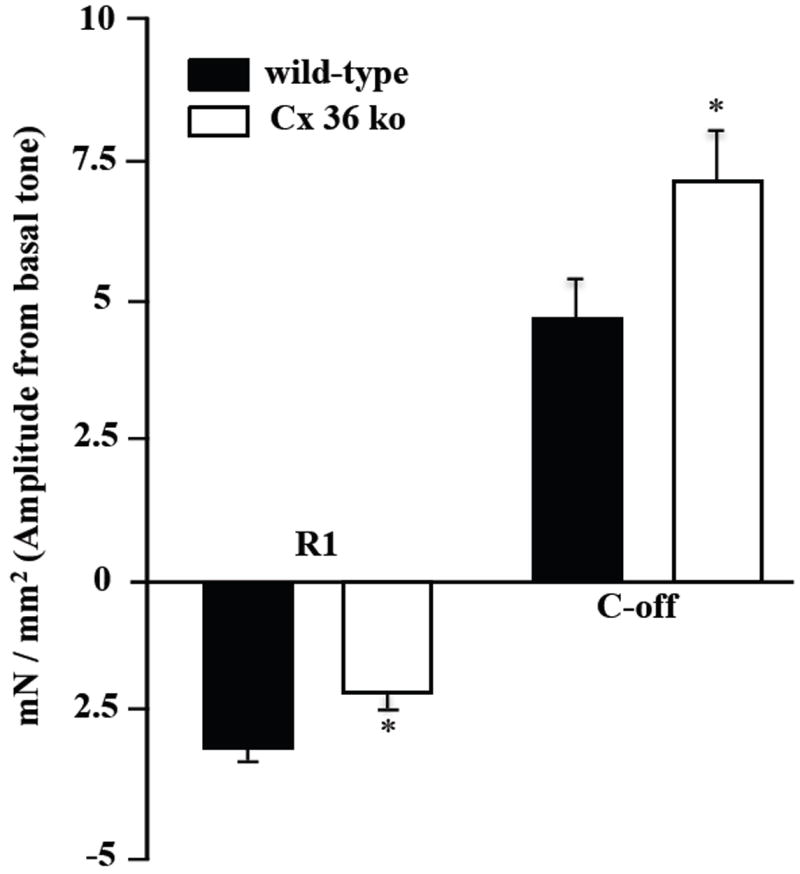

3.6. Mechanical responses to electrical field stimulation

We next investigated how distal colonic longitudinal muscle strips from WT and Cx36 ko mice respond to parameters of EFS typically used for eliciting activity in enteric neurons [30]. As shown by a representative recording of WT colonic responses to EFS (Fig. 4A), the stimulation induced a fast relaxation (R1: 2.9 ± 0.2 mN/mm2) that persisted during the stimulus. A rebound contraction (off contraction, C-off: 4.62 ± 0.6 mN/mm2) occurred at the end of the stimulus (Fig. 4A). In colonic strips from Cx36 ko mice, the magnitudes of EFS-induced relaxation were significantly decreased by about 50% (Fig. 4B, Fig. 5). In 5/20 colonic samples, this relaxation was replaced by a contraction (C1: 3.84 ± 0.5 mN/mm2) (Fig. 4C). The C-off contraction seen at the end of the EFS was 1.5-fold significantly greater in colonic strips from Cx36 ko mice compared with those from WT mice (Fig. 4A and B, Fig. 5). As in the case of basal tone values observed during measurements of spontaneous muscle activity, there were no differences in basal tone prior to the onset of the applied EFS to colonic strips from WT (7.6 ± 0.7 mN/mm2) vs. those from Cx36 ko (7.9 ± 0.6 mN/mm2) mice. This excludes any confounding contribution of basal tone levels to the amplitude measurements. The EFS-induced responses were abolished in the presence of the Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX, 2 μM), which prevents neuronal action potential propagation, indicating the neuronal origin of the EFS response (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Recordings of colonic mechanical responses to EFS in organ bath preparations of muscle strips from adult WT and Cx36 ko mice. A: In wild-type mice, EFS induced a biphasic response seen as a first relaxation (R1) followed by an off-contraction (C-off) at the end of the applied stimulus. B: In Cx36-deficient mice, EFS induced a similar biphasic response, but where the relaxation (R1) during the stimulus was significantly reduced and followed at the end of stimulation by a significantly increased C-off. C: Example from 25% of colonic muscle strips where R1 was replaced by a contraction (C1) followed by a similar increased C-off as seen in all strips. Traces are expressed as mN and do not reflect the integrations of cross-sectional area. Dashed lines represent mean basal tone of colonic strips under isometric conditions, which were unchanged in strips from WT vs. Cx36 ko.

Figure 5.

Summary of EFS-evoked relaxation and contraction of colonic muscle strips from WT and Cx36 ko mice. Amplitude represents response deviation from basal tone. The electrically evoked relaxation response (R1) was significantly reduced 31%, and C-off contraction was significantly increased by 51% in colonic tissues from Cx36 ko vs. wild-type mice. Values are expressed as mN per muscle cross-sectional area (mm2) and represent means ± SEMs (unpaired t-test, *p < 0.05, n = 20 samples per group). Asterisk indicates significant difference between WT vs. and Cx36 ko. EFS parameters were monophasic train with a rate of 0.02 train per second, train duration of 10 seconds, pulse rate of 16 pulses per second, pulse duration of 0.5 ms, pulse delay of zero seconds, and a voltage of 24 V.

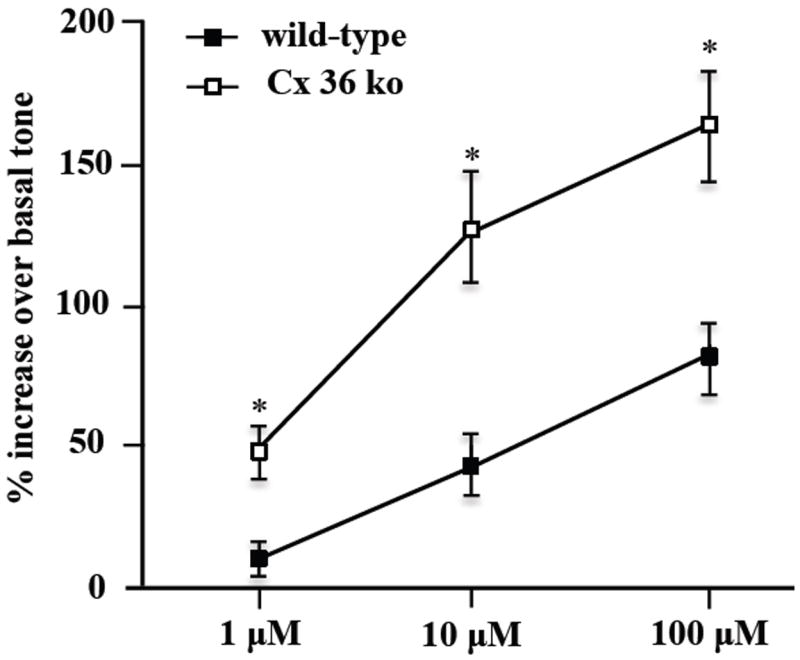

3.8. Gut responses to carbachol

Colonic muscle strips from WT and Cx36 ko mice were compared for their contractility responsiveness to stimulation by the broad spectrum (muscarinic and nicotinic) cholinergic receptor agonist carbachol, which can act on both enteric neurons and gut smooth muscle [1,31-33]. A one-minute exposure of muscle strips to increasing concentrations of carbachol (1-100 μM) induced contractions in colonic strips from both WT and Cx36 ko mice (Fig. 6). However, despite lack of an effect to Cx36 ablation on resting basal tone, carbachol-induced contractile responses in Cx36 ko vs. WT colonic samples were significantly greater by 36.6 %, 83.2% and 81.1% at the 1 μM, 10 μM and 100 μM concentrations of carbachol tested, respectively, indicating that Cx36 ko mice have altered cellular physiology in gut at locations of cholinergic agonist sites of action or at locations downstream of these sites.

Figure 6.

Carbachol-induced contraction of colonic muscle strips from WT and Cx36 ko mice. Maximum tension generated by muscle strips in response to carbachol was calculated as percentage elevation over muscle basal tone before addition of 1, 10 and 100 μM carbachol. Carbachol-induced contraction was significantly increased in colonic strips from Cx36 ko compared to WT mice (asterisks). Value are expressed as means ± and SEMs, ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey-test, *p < 0.05, n = 20.

4. Discussion

In this report, we present anatomical and physiological evidence implicating a role for interneuronal communication via gap junctions in the ENS. Our results add a new dimension to the already complex circuitry and long list of transmitters and neuromodulators whereby communication between enteric neurons governs contractile activity of the intestinal system. Of course, a great deal remains to be explored concerning enteric neuronal gap junctions, not the least of which include; i) electron microscopic identification of ultrastructurally-defined, Cx36-containing gap junctions between enteric neuronal elements; ii) further characterization of the subclasses of neurons that are linked by gap junctions; iii) electrophysiological demonstration that these junctions mediate functional electrical and dye-coupling between enteric neurons; iv) determination of whether contractile activity in other regions of gut (i.e., duodenum, jejunum, ileum), as well as contractile activity of circular muscle, display similar deviations in Cx36 ko mice as observed in longitudinal muscle of colon in these mice; and v) elucidation of why electrical coupling between a subpopulation of enteric neurons is required for their normal operation in gut enteric circuitry. Some of these points may be considered in the context of current literature.

4.1. Cx36 localization at gap junctions

In the many CNS structures where Cx36-containing gap junctions between neurons have been found, immunofluorescence labelling for Cx36 invariably occurs as puncta localized to the surface of neuronal somata and dendrites, or to axon terminals in cases where these puncta are found at morphologically mixed synapses [23-29]. Little if any Cx36 is detectable in cell cytoplasm, possibly due to masking of Cx36 antibody epitope or to its rapid transport to plasma membrane following synthesis. This immunolabelling pattern is perhaps fortuitous because it reveals specifically the cellular locations of Cx36-containing gap junctions, unmasked by the many other subcellular sites at which Cx36 must occur during its trafficking to and from these gap junctions. This conclusion is supported by the strong correlation between the CNS locations and/or neuron types that display Cx36-puncta and sites at which ultrastructurally-defined neuronal gap junctions have been identified, including those containing Cx36 [17-19,34-37]. Labelling patterns of Cx36 observed in the CNS also apply to those in gut, at least under the tissue preparation conditions presently employed. The disadvantage of this exclusively punctate immunofluorescence labelling pattern is that it does not always immediately reveal the cell types to which Cx36-puncta belong, except in cases where neurons bearing these puncta can be identified by their morphological features or by simultaneous labelling of correctly chosen marker proteins. However, as in the CNS, localization of Cx36-puncta around the periphery of neuronal somata and at intersections between neuronal processes in gut almost certainly reveals sites of gap junction formation at neuronal plasma membranes. An entirely separate issue not examined in the present study is whether one of more of the other connexins expressed in gut (i.e., Cx40, Cx43, Cx45) and so far localized to non-neuronal cells (see Introduction) also participate in neuronal gap junction formation. Resolution of this will likely require comprehensive ultrastructural immunohistochemical approaches.

4.2. Types of neurons forming gap junctions

It appears that Cx36-containing gap junctions occur between only a very limited population of enteric neurons. In both mouse and rat, Cx36-puncta were localized very near or at appositions between a subpopulation of nNOS-positive neuronal cell bodies within the myenteric plexus. In mice, only a couple of rare examples among hundreds of nNOS-immunoreactive neuronal somata were found where these puncta were associated with nNOS-positive adjacent to nNOS-negative cells. It should be noted that collection of data from mouse gut was challenging due to the weak fixation required for immunofluorescence visualization of Cx36; tissue sections were fragile and occasionally dislodged from slides during immunohistochemical processing. This was not the case using the same fixation of rat gut, where labelling of Cx36 was robust and all or nearly all Cx36-puncta were localized to nNOS-positive neuronal somata or their albeit weakly labelled processes near these somata. In rat, it was particularly evident that this association occurred in each segment of gut (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon), suggesting that Cx36-containing gap junctions link nNOS-positive neurons distributed along the entire length of the intestinal system.

The distribution and anatomical features of neurons expressing nNOS have been well studied in the gut of a variety of species [38-44], and have been characterized as Dogiel type-I neurons distributed in the myenteric plexus and rarely in the submucosal plexus of the small intestine, and in both plexuses of the large intestine [45]. Regarding the submucosal plexus, the scarcity of nNOS-positive neurons in this plexus of the small intestine parallels the absence of Cx36-puncta in this plexus of small intestine, and nNOS-containing neurons in the submucosal plexus of the large intestine appear to be devoid of Cx36-puncta. In the myenteric plexus, nNOS-containing neurons have been functionally characterized as short- and long-projecting inhibitory circular muscle motor neurons, descending local reflex interneurons and a small percentage representing inhibitory longitudinal muscle motor neurons [2,45]. Our results suggest the presence of Cx36-containing gap junctions forming electrical synapses between one or more but not all of the four different classes of enteric neurons that express nNOS. Alternatively, it may be that subpopulations of neurons within one or more of these four classes form gap junctions, with junctions between neurons restricted to coupling those of similar class (homologous coupling) or coupling those of different classes (heterologous coupling).

The present data sets do not allow us to distinguish between the above possibilities. Our results from studies of EGFP-Cx36 mice do, however, provide some additional clues. Notwithstanding that we were unable to verify directly whether EGFP expression in these mice is a reliable reporter for Cx36 expression, the co-localization of the vast majority of labelling for EGFP with a subset of nNOS-positive fibers is in accordance with the association of Cx36-puncta with a subpopulation of nNOS-positive neurons. Lack of overlap of a minority of EGFP-positive fibers with nNOS suggests either Cx36 expression in a non-nNOS-containing neuronal population, false-negative detection of nNOS or false-positive reporter expression of EFGP. In the myenteric plexus, our results showing co-localization of EGFP with a subset of fibers and terminals containing dynorphin A suggests Cx36 expression by a subpopulation of nNOS-positive long-projecting inhibitory circular muscle motor neurons that selectively express dynorphin A [2]. However, the dense labelling for EGFP we found in myenteric plexus and sparse labelling in the muscle layers of gut would be more consistent with EGFP expression in descending local reflex interneurons, which contain nNOS and innervate enteric ganglia [2]. In attempts to reconcile all of the above possibilities, it may simply be considered that just as neurotransmitter markers distinguish anatomically and functionally characterized enteric neuronal populations, so to Cx36 expression and electrical synapse formation distinguishes an as yet poorly understood population of enteric neurons that contains its own distinct set of transmitter and neuromodulator markers.

4.3. Spontaneous gut contractility after Cx36 ablation

This report is the first to demonstrate an abnormal phenotype in contractile activity of gut after Cx36 ablation. Our organ bath studies revealed that loss of Cx36 caused an increase in the amplitude of colonic spontaneous smooth muscle contractions, reduced or abolished EFS-induced relaxation and increased the contractile response after cessation of EFS. The patterns of activity of normal murine colon we observed in organ bath preparations were typical of those generally reported [30] and may be considered in the context of current views of how the ENS integrates sensory information from multiple locations and ultimately generates appropriate motility responses. Spontaneous myogenic contractile activity of murine colonic circular and longitudinal muscle is characterized by rhythmic and phasic contractions originating in peacemaker cells (i.e., interstitial cells of Cajal) intercalated among enteric neurons and gut smooth muscle cells [13] which is under tonic neural influence [46]. Final effector excitatory motor neurons that release acetylcholine (ACh) and tachykinins are mainly implicated in increasing the pressure waves and exert a tonic excitatory effect on basal tone [47] Relaxation of the gastrointestinal smooth muscle, which is a feature of several physiologic digestive reflexes, originates from spontaneously active inhibitory motor neurons that maintain gut smooth musculature under tonic inhibition. This process appears to occur largely by mechanisms involving release of non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC) (e.g., NO) transmitters from enteric nerves, as suggested by increased muscle contractility observed in the presence of nNOS inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) or TTX, supporting the role of enteric neurons and neuronal NO [46] Thus, NO produced by nNOS in nitrergic neurons in the ENS is viewed as a neurotransmitter that acts on NO-sensitive guanylyl cyclase in its effector cells, thereby decreasing the tone of various types of smooth muscle, including colonic musculature [48]. More specifically, there is evidence for a major role of NO as a NANC neurotransmitters in longitudinal muscle of mouse distal colon [49]. As basal tone was unaffected in colon from Cx36 ko mice, our results on spontaneous contractile properties of gut musculature from these mice may be considered in relation to concepts surrounding the role of nitrergic neurons in regulating gut motility. We suggest that the increased amplitude of spontaneous contractions in the absence of Cx36 reflects compromised activity of nitrergic inhibitory neurons, a possibility consistent with the localization of Cx36-puncta to nNOS-containing enteric neurons in normal mice.

4.4. Electrically-induced gut contractility after Cx36 ablation

Colonic muscle strips from normal mice produced a biphasic response to EFS, consisting of an inhibitory relaxation (R1) component and an excitatory contractile (C-off) component upon termination of EFS. Both of these components were abrogated in the presence of TTX, demonstrating a neuronal origin of the responses. Current evidence in rodents suggests that inhibitory NANC neurotransmitters are released during enteric nerve stimulation. We and others have demonstrated that the relaxation response in the proximal and distal rat and mouse colon is significantly blocked by L-NAME, suggesting that NO contributes to the mediation of this relaxation [46,50,51]. This is consistent with the absence of EFS-induced relaxation in nNOS-deficient mice [52]. The C-off results mainly from acetylcholine release from excitatory motor neurons, because it is decreased in the presence of atropine [50]. The C-off excitatory response also appears to be subject to regulation by NO, as suggested by findings that the amplitude of the C-off contraction is significantly increased in the presence of L-NAME [46]. Based on the foregoing and as in the case of spontaneous SMA, we may infer that NANC enteric neurons, specifically nitrergic neurons, in Cx36 ko mice have reduced inhibitory capacity to elicit smooth muscle relaxation following their excitation by EFS.

4.4. Altered responses of Cx36 ko gut to carbachol

The increased contractile responsiveness of colonic muscle strips from Cx36 ko vs. WT mice to cholinergic receptor stimulation with carbachol is more difficult to align with our favoured scenario of functionally compromised nitrergic enteric neurons in these mice. For example, carbachol can act directly on smooth muscle, raising the possibility of altered smooth muscle sensitivity to cholinergic stimulation. However, it is also possible that cholinergic transmission contributes to activation of nitrergic neurons [53]. In this event, a reduced capacity for cholinergic activation of these neurons, or any other means of their activation for that matter, arising from a loss of Cx36 could result in partial withdrawal of their tonic inhibitory control of smooth muscle, which could be manifest as exaggerated responsiveness of smooth muscle to direct muscle stimulation, in this case with carbachol. Distinguishing between these possibilities will be aided by pharmacological dissection of the basis for the altered cholinergic responsiveness.

4.5. Basis for compromised nitrergic neuronal activity after Cx36 ablation

Assuming further work supports the existence of gap junctional coupling between nitrergic neurons in the rodent intestinal system, how could the loss of Cx36 expression in a subpopulation of these neurons account for what we postulate results in their reduced activity and EFS responsiveness? As noted in the Introduction, neuronal gap junctions forming electrical synapses between neurons in the CNS enable synchronization of subthreshold membrane oscillations within networks of gap junctionally coupled neurons [17-19]. It is thought that excitatory inputs subthreshold for neuronal activation are distributed via neuronal gap junctions in such networks, bringing coupled neurons collectively closer to threshold for firing, and ultimately resulting in their recruitment into ensembles of neurons with synchronized firing. Electrical synapses similarly distribute inhibitory input and hyperpolarization within gap junctionally coupled networks [54,55]. Gene deletion of Cx36 in mice is accompanied by functional deficits in neuronal network properties [18,19]. In Cx36 ko mice, we found a profound reduction in capacity to evoke presynaptic inhibition of primary afferent fibers, and proposed that this may be due to a deficiency of gap junctions coupling between spinal cord interneurons that mediate this inhibition [23]. Similarly, it is conceivable that synchronized concerted activity afforded by electrical synapses between a distinct set of nNOS-containing enteric neurons is required for their maximal tonic or electrically evoked inhibitory influence on gut smooth muscle contractility. If the level of activity of these cells is correlated with levels of their NO production [56], then all cell types that are targets of NO release from this set of coupled nNOS-containing cells may be affected by their reduced activity in Cx36 ko mice, including smooth muscle cells and other neurons, as well as perhaps interstitial cells of Cajal. Actions on the latter cells could impact on their pacemaker activities. A further level of complexity may be envisioned based on observations that gap junctionally coupled inhibitory interneurons in some brain structures such as the cerebellar cortex [57] include those that express nNOS [56], and that NO is among the many transmitters capable of regulating gap junctional coupling between central neurons [58,59]. If similar NO-mediated modulation of neuronal gap junctional coupling is extant in the gut, then the activity of the set of coupled nNOS-containing neurons may be subject to feedback regulation through an effect of NO on their junctional coupling.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Image from myenteric plexus of adult mouse colon immunolabelled for Cx36, nNOS and counterstained with fluorescence blue Nissl, showing a rare example of Cx36-puncta (arrow) localized between a nNOS-positive (green) and a nNOS-negative (blue, arrowhead) neuronal somata.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN 436390-2013), Manitoba Health Research Council and Canada Foundation for Innovation to JE Ghia, and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to J.I.N. (MOP 106598), and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS31027, NS44010, NS44295) to JE Rash with sub-award to JIN. We thank B. McLean for excellent technical assistance, Dr. B.D. Lynn for help with genotyping EGFP-Cx36 transgenic mice, and Dr. D. Paul (Harvard University) for providing breeding pairs of Cx36 knockout and wild-type mice.

Abbreviations

- C-off

off contraction

- Cx36

connexin36

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- ENS

enteric nervous system

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- GABAergic

gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic

- GJIC

gap junctional intercellular communication

- ko

knockout

- NANC

non-adrenergic non-cholinergic

- mN

millinewton

- NO

nitric oxide

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- SMA

smooth muscle activity

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Furness JB. Types of neurons in the enteric nervous system. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;81:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(00)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furness JB, Jones C, Nurgali K, Clerc N. Intrinsic primary afferent neurons and nerve circuits within the intestine. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;72:143–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood JD. Integrated systems Physiology; from molecule to function. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; San Bernardino, CA, USA: 2011. Enteric Nervous System (The brain-In-The-Gut) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berezin I, Huizinga JD, Daniel EE. Interstitial cells of Cajal in the canine colon: a special communication network at the inner border of the circular muscle. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273:42–51. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel EE, Wang YF. Gap junctions in intestinal smooth muscle and interstitial cells of Cajal. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;47:309–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991201)47:5<309::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabella G, Blundell D. Gap junctions of the muscles of the small and large intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 1981;219:469–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00209987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans WH, Martin PE. Gap junctions: structure and function (Review) Mol Membr Biol. 2002;19:121–36. doi: 10.1080/09687680210139839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho WJ, Daniel EE. Proteins of interstitial cells of Cajal and intestinal smooth muscle, colocalized with caveolin-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G571–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00222.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkelsen HB, Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Rumessen JJ. Immunohistochemical localization of a gap junction protein (connexin43) in the muscularis externa of murine, canine, and human intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;274:249–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00318744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura K, Kuraoka A, Kawabuchi M, Shibata Y. Specific localization of gap junction protein, connexin45, in the deep muscular plexus of dog and rat small intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:487–94. doi: 10.1007/s004410051077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seki K, Komuro T. Immunocytochemical demonstration of the gap junction proteins connexin 43 and connexin 45 in the musculature of the rat small intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;306:417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YF, Daniel EE. Gap junctions in gastrointestinal muscle contain multiple connexins. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G533–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.2.G533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel EE, Thomas J, Ramnarain M, Bowes TJ, Jury J. Do gap junctions couple interstitial cells of Cajal pacing and neurotransmission to gastrointestinal smooth muscle? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2001;13:297–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doring B, et al. Ablation of connexin43 in smooth muscle cells of the mouse intestine: functional insights into physiology and morphology. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:333–42. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park KJ, Hennig GW, Lee HT, Spencer NJ, Ward SM, Smith TK, Sanders KM. Spatial and temporal mapping of pacemaker activity in interstitial cells of Cajal in mouse ileum in situ. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1411–27. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00447.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frinchi M, Di Liberto V, Turimella S, D’Antoni F, Theis M, Belluardo N, Mudo G. Connexin36 (Cx36) expression and protein detection in the mouse carotid body and myenteric plexus. Acta Histochem. 2013;115:252–6. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Electrical coupling and neuronal synchronization in the Mammalian brain. Neuron. 2004;41:495–511. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connors BW, Long MA. Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:393–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hormuzdi SG, Filippov MA, Mitropoulou G, Monyer H, Bruzzone R. Electrical synapses: a dynamic signaling system that shapes the activity of neuronal networks. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1662:113–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett MV. Gap junctions as electrical synapses. J Neurocytol. 1997;26:349–66. doi: 10.1023/a:1018560803261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deans MR, Gibson JR, Sellitto C, Connors BW, Paul DL. Synchronous activity of inhibitory networks in neocortex requires electrical synapses containing connexin36. Neuron. 2001;31:477–85. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermillion DL, Collins SM. Increased responsiveness of jejunal longitudinal muscle in Trichinella-infected rats. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:G124–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.1.G124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bautista W, Nagy JI, Dai Y, McCrea DA. Requirement of neuronal connexin36 in pathways mediating presynaptic inhibition of primary afferents in functionally mature mouse spinal cord. J Physiol. 2012;590:3821–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curti S, Hoge G, Nagy JI, Pereda AE. Synergy between electrical coupling and membrane properties promotes strong synchronization of neurons of the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4341–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6216-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Lynn BD, Nagy JI. The effector and scaffolding proteins AF6 and MUPP1 interact with connexin36 and localize at gap junctions that form electrical synapses in rodent brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:166–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bautista W, Nagy JI. Connexin36 in gap junctions forming electrical synapses between motoneurons in sexually dimorphic motor nuclei in spinal cord of rat and mouse. Eur J Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ejn.12439. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynn BD, Li X, Nagy JI. Under construction: building the macromolecular superstructure and signaling components of an electrical synapse. J Membr Biol. 2012;245:303–17. doi: 10.1007/s00232-012-9451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagy JI. Evidence for connexin36 localization at hippocampal mossy fiber terminals suggesting mixed chemical/electrical transmission by granule cells. Brain Res. 2012;1487:107–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagy JI, Bautista W, Blakley B, Rash JE. Morphologically mixed chemical-electrical synapses formed by primary afferents in rodent vestibular nuclei as revealed by immunofluorescence detection of connexin36 and vesicular glutamate transporter-1. Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.056. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin GR, Alvarez AL, Bashashati M, Keenan CM, Jirik FR, Sharkey KA. Endogenous cellular prion protein regulates contractility of the mouse ileum. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:e412–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goyal RK, Hirano I. The enteric nervous system. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1106–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604253341707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakamoto T, Unno T, Kitazawa T, Taneike T, Yamada M, Wess J, Nishimura M, Komori S. Three distinct muscarinic signalling pathways for cationic channel activation in mouse gut smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2007;582:41–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zholos AV. Regulation of TRP-like muscarinic cation current in gastrointestinal smooth muscle with special reference to PLC/InsP3/Ca2+ system. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:833–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rash JE, Olson CO, Davidson KG, Yasumura T, Kamasawa N, Nagy JI. Identification of connexin36 in gap junctions between neurons in rodent locus coeruleus. Neuroscience. 2007;147:938–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rash JE, et al. Connexin36 vs. connexin32, “miniature” neuronal gap junctions, and limited electrotonic coupling in rodent suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience. 2007;149:350–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rash JE, Staines WA, Yasumura T, Patel D, Furman CS, Stelmack GL, Nagy JI. Immunogold evidence that neuronal gap junctions in adult rat brain and spinal cord contain connexin-36 but not connexin-32 or connexin-43. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7573–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rash JE, Yasumura T, Dudek FE, Nagy JI. Cell-specific expression of connexins and evidence of restricted gap junctional coupling between glial cells and between neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1983–2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01983.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aimi Y, Kimura H, Kinoshita T, Minami Y, Fujimura M, Vincent SR. Histochemical localization of nitric oxide synthase in rat enteric nervous system. Neuroscience. 1993;53:553–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90220-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ekblad E, Mulder H, Uddman R, Sundler F. NOS-containing neurons in the rat gut and coeliac ganglia. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1323–31. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freytag C, Seeger J, Siegemund T, Grosche J, Grosche A, Freeman DE, Schusser GF, Hartig W. Immunohistochemical characterization and quantitative analysis of neurons in the myenteric plexus of the equine intestine. Brain Res. 2008;1244:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jarvinen MK, Wollmann WJ, Powrozek TA, Schultz JA, Powley TL. Nitric oxide synthase-containing neurons in the myenteric plexus of the rat gastrointestinal tract: distribution and regional density. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;199:99–112. doi: 10.1007/s004290050213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li ZS, Young HM, Furness JB. Nitric oxide synthase in neurons of the gastrointestinal tract of an avian species, Coturnix coturnix. J Anat. 1994;184(Pt 2):261–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nichols K, Krantis A, Staines W. Histochemical localization of nitric oxide-synthesizing neurons and vascular sites in the guinea-pig intestine. Neuroscience. 1992;51:791–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90520-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toole L, Belai A, Burnstock G. A neurochemical characterisation of the golden hamster myenteric plexus. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;291:385–94. doi: 10.1007/s004410051008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furness JB, Li ZS, Young HM, Forstermann U. Nitric oxide synthase in the enteric nervous system of the guinea-pig: a quantitative description. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;277:139–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00303090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghia JE, Crenner F, Rohr S, Meyer C, Metz-Boutigue MH, Aunis D, Angel F. A role for chromogranin A (4-16), a vasostatin-derived peptide, on human colonic motility. An in vitro study Regul Pept. 2004;121:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Priem EK, Lefebvre RA. Investigation of neurogenic excitatory and inhibitory motor responses and their control by 5-HT(4) receptors in circular smooth muscle of pig descending colon. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;667:365–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forstermann U, Closs EI, Pollock JS, Nakane M, Schwarz P, Gath I, Kleinert H. Nitric oxide synthase isozymes. Characterization, purification, molecular cloning, and functions. Hypertension. 1994;23:1121–31. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satoh Y, Takeuchi T, Yamazaki Y, Okishio Y, Nishio H, Takatsuji K, Hata F. Mediators of nonadrenergic, noncholinergic relaxation in longitudinal muscle of the intestine of ICR mice. J Smooth Muscle Res. 1999;35:65–75. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.35.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayer S, Jellali A, Crenner F, Aunis D, Angel F. Functional evidence for a role of GABA receptors in modulating nerve activities of circular smooth muscle from rat colon in vitro. Life Sci. 2003;72:1481–93. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghia JE, Pradaud I, Crenner F, Metz-Boutigue MH, Aunis D, Angel F. Effect of acetic acid or trypsin application on rat colonic motility in vitro and modulation by two synthetic fragments of chromogranin A. Regul Pept. 2005;124:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim CD, Goyal RK, Mashimo H. Neuronal NOS provides nitrergic inhibitory neurotransmitter in mouse lower esophageal sphincter. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G280–4. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.2.G280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rand MJ, Li CG. Modulation of acetylcholine-induced contractions of the rat anococcygeus muscle by activation of nitrergic nerves. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:1479–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Connors BW, Zolnik TA, Lee SC. Enhanced functions of electrical junctions. Neuron. 2010;67:354–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vervaeke K, Lorincz A, Gleeson P, Farinella M, Nusser Z, Silver RA. Rapid desynchronization of an electrically coupled interneuron network with sparse excitatory synaptic input. Neuron. 2010;67:435–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vincent SR. Nitric oxide neurons and neurotransmission. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;90:246–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mann-Metzer P, Yarom Y. Electrotonic coupling synchronizes interneuron activity in the cerebellar cortex. Prog Brain Res. 2000;124:115–22. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(00)24012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Donnell P, Grace AA. Cortical afferents modulate striatal gap junction permeability via nitric oxide. Neuroscience. 1997;76:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rorig B, Sutor B. Nitric oxide-stimulated increase in intracellular cGMP modulates gap junction coupling in rat neocortex. Neuroreport. 1996;7:569–72. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199601310-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Image from myenteric plexus of adult mouse colon immunolabelled for Cx36, nNOS and counterstained with fluorescence blue Nissl, showing a rare example of Cx36-puncta (arrow) localized between a nNOS-positive (green) and a nNOS-negative (blue, arrowhead) neuronal somata.