Abstract

This article describes U.S. state policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy, using data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS). Specifically, this study examines trends in policies enacted by states over time and types of policies enacted across states in the U.S., with a focus on whether laws were supportive or punitive toward women. Findings revealed substantial variability in characteristics of policies (19 primarily supportive, 12 primarily punitive, 12 with a mixed approach, and 8 with no policies). Findings underscore the need to examine possible consequences of policies, especially of punitive policies and “mixed” approaches.

Keywords: alcohol consumption, pregnancy, women, policy, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, prevention

Interest in alcohol and drug issues among women in the United States emerged in the 1970s in tandem with the broader women’s health and reproductive rights movements and emerging public attention to related concerns such as drinking and driving and addiction treatment (Kaskutas, 1995). It was also in the 1970s that the term Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) was introduced to identify a specific pattern of developmental delays, facial anomalies, and neurological problems with children born to women who consumed high levels of alcohol during pregnancy. In more recent years, the term fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) has emerged as an umbrella term to describe a wide range of possible effects that can occur as a result of prenatal exposure to alcohol (Warren & Hewitt, 2009; Warren, Hewitt, & Thomas, 2011). Public attention to women’s drinking has continued in the United States, in part because of concerns about the potential effects of alcohol consumption, particularly heavier drinking, during pregnancy (Wilsnack, Kristjanson, Wilsnack, & Crosby, 2006). These concerns have been translated into federal initiatives including the development of policies requiring warning labels on alcoholic beverages (Kaskutas, 1995; Warren & Hewitt, 2009) and mandates that states receiving federal funding for treatment of substance use disorders prioritize admission for pregnant women (Grella, 2008; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA]b).

Analyses of policies on the state level have generally focused primarily or exclusively on policy responses to illicit drug use during pregnancy (Chavkin, Breitbart, Elman, & Wise, 1998; Dailard & Nash, 2000; Figdor & Kaeser, 1998; Guttmacher Institute, 2013; Kang, 2003; Lester, Andreozzi, & Appiah, 2004; Ondersma, Simpson, Brestan, & Ward, 2000). By contrast, little attention has been paid to describing policies relating to alcohol use during pregnancy. The lack of attention is significant for a number of reasons. First, although alcohol use generally declines after women recognize that they are pregnant (Ethen et al., 2009), alcohol use during pregnancy is much more common than drug use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011) and the effects of (especially heavier) alcohol use are well documented (O’Leary & Bower, 2012; Patra et al., 2011; Warren et al., 2011). Second, policies, such as priority substance abuse treatment for pregnant women could increase the proportion of pregnant who complete treatment (Albrecht, Lindsay, & Terplan, 2011). Third, policies such as requirements for reporting maternal alcohol use during pregnancy to Child Protective Services (CPS) could drive women from prenatal care, as has been found for drug use during pregnancy (Murphy & Rosenbaum, 1999; Roberts & Pies, 2010). Fourth, by creating an environment of mistrust between women and providers, policy contexts that allow criminal justice prosecutions or require CPS reporting related to alcohol use during pregnancy may influence the effectiveness of alcohol-related interventions such as screening and brief interventions, which are widely recommended for pregnant women (Anthony, Austin, & Cormier, 2010; Goodman & Wolff, 2013; Roberts & Nuru-Jeter, 2010), particularly for women who drink at risk levels (ACOG, 2011b). Such an environment of mistrust may make women less likely to disclose alcohol use to providers and may lead women to disengage emotionally and physically from prenatal care, especially if reporting to CPS is a possible result of screening (Roberts & Nuru-Jeter, 2010). However, these state-level policies related to alcohol use have, for the most part, not been studied.

The importance of characterizing state-level policies related to alcohol and pregnancy is underscored by a recent American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee Opinion about substance abuse reporting and pregnancy (ACOG, 2011a). This opinion addresses the provider role in relation to criminal justice and child welfare responses to both alcohol and drug abuse during pregnancy. The ACOG opinion stated that obstetricians-gynecologists need to provide appropriate medical care to pregnant women with alcohol and drug problems and to work to ensure that appropriate treatment is available. The opinion also emphasized that, in states that mandate reporting, obstetricians-gynecologists should work with policy makers and legislators to retract punitive legislation, such as those that would expose women to involuntary commitment, incarceration, or loss of custody of children.

The Guttmacher Institute regularly reports on state policies relating to illicit drug use during pregnancy (Guttmacher Institute, 2011, 2013). Thus, health care providers, social workers, and maternal and child health practitioners have a readily available source for information about policies relating to drug use during pregnancy. However, there is a dearth of literature describing and characterizing state policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy, making it difficult for health care providers, social workers, and maternal and child health practitioners to characterize the policy environment in their state. Information about state policies relating to alcohol use during pregnancy, which includes annual statutory and regulatory data from all fifty states and the District of Columbia, exists in National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)’s Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) (NIAAA 2013a). However, the information related to alcohol use during pregnancy from APIS has not yet been synthesized and described. Describing such policies would give obstetricians and other providers who care for pregnant women a tool to understand the policy context in which they are practicing and could also set the stage for evaluations of the effects of these policies. Some policies exist only for alcohol and not for drugs, such as mandatory warning signs. Also, policies within a given state may differ for alcohol and drugs. Thus, separate documentation of policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy is needed.

As a first step toward understanding trends and characteristics of policies specific to alcohol use during pregnancy, we explore the following research questions: (a) What are the trends in policies that have been enacted by states over time? (b) What types of policies were enacted as of January 1, 2012 across states in the United States and to what degree are policies supportive or punitive?

Methods

Data for this study were drawn from the Alcohol Policy Information Systems (APIS), which provides federal and state statutory and regulatory data for 33 alcohol policy topics, including six related to alcohol use during pregnancy (NIAAAa). APIS codes its legal data to reflect the presence or absence of policies in each jurisdiction as well as variables within many policy topics. For example, with respect to policies related to posting mandatory warning signs about health risks associated with alcohol consumption during pregnancy, APIS provides information about who is required to post signs (such as on and off-premises retailers, types of health care providers) and the details of display requirements (such as whether signage in a language other than English is required). Hence, rather than simply noting whether or not a jurisdiction contains statutes or regulations on a given policy topic, APIS provides data on a host of relevant variables within each policy topic. This permits scholars to assess differences across jurisdictions that, on the surface, look similar as well as to delve deeply into the nature of the law in individual jurisdictions. Polychotomous variables that address variation and exceptions in laws are more useful in descriptive policy studies than dichotomous “Law/No Law” variables, which may obscure variability in law (Tremper, Thomas, & Wagenaar, 2010).

For the purposes of this analysis, six APIS policy topics related to alcohol and pregnancy issues were examined: (a) mandatory signs posted in establishments that sell or serve alcohol to warn patrons of the impact of alcohol use during pregnancy; (b) priority treatment for pregnant women with alcohol dependence; (c) prohibitions against criminal prosecution of women who have exposed a fetus to alcohol; (d) mandatory reporting by health care providers and related personnel of indicators of fetal exposure to alcohol; (e) use of indicators of alcohol use or abuse during pregnancy as evidence of child abuse or child neglect; and (f) civil commitment of pregnant women who use or abuse alcohol. Table 1 provides a description from APIS system for each of the six policy areas related to alcohol and pregnancy.

Table 1.

Alcohol Policy Information Systems (APIS) topic areas and description related to alcohol and pregnancy.

| APIS POLICY TOPIC AREA | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Mandatory warning signs | These provisions require that notices be posted in settings, such as licensed premises, where alcoholic beverages are sold and health care facilities where pregnant women receive treatment. Policy provisions specify who must post warning signs, the specific language required on the signs, and where signs must appear. The warning language required across jurisdictions varies in detail, but in each case, warns of the risks associated with drinking during pregnancy |

| Priority Treatment | This area addresses statutes and regulations mandating priority access to substance abuse treatment for pregnant and postpartum women who abuse alcohol. |

| Limitations on Criminal Prosecution | In contrast, to civil commitment laws, limitations on criminal prosecution statutes prohibit use of the results of medical tests, such as prenatal screenings or toxicology tests, as evidence in the criminal prosecutions of women who may have caused harm to a fetus or a child. |

| Reporting Requirements | Reporting requirements concerns mandates to report suspicion or evidence of alcohol use or abuse by women during pregnancy. Evidence may consist of screening and/or toxicological testing of pregnant women or toxicological testing of babies after birth. |

| Legal Significance for Child Abuse/Child Neglect | This area addresses the legal significance of a woman’s conduct prior to birth of a child and of damage caused in utero. |

| Civil Commitment | Civil commitment refers either to mandatory involuntary commitment of a pregnant woman to treatment or mandatory involuntary placement of a pregnant woman in protective custody of the State for the protection of a fetus from prenatal exposure to alcohol. |

Research question one was examined by creating a dichotomous law/no law variable for laws enacted by January 1 of each year in each of the six policy domains related to alcohol consumption during pregnancy between 2003 and 2012, the most recent year for which APIS data were available at the time this article was written. Changes in the law over time were restricted to these years (2003 – 2012) for which data in all six policy areas were available in APIS. Research question two was analyzed in two phases. First, states with statutes or regulations in each category based on APIS data as of January 1, 2012 were identified. Second, text for the legal citations listed in APIS for each policy area were collected and organized by state. Citation text was collected primarily through state-specific public access sites and Westlaw, an authoritative, on-line legal database. In the current study, variations in law were noted for laws related to priority treatment, reporting requirements, and laws related to child welfare and neglect (details provided below).

Two predominant approaches to addressing alcohol use in pregnancy and the harms associated with it have been enacted by federal and state governments. The first can be described as supportive and seeks to provide information, early intervention, and treatment and services to pregnant women who use or abuse alcohol. For example, supportive approaches include laws that mandate priority treatment in substance abuse treatment programs and laws that allocate public funding for treatment programs. The second can be described as punitive and seeks to control pregnant women’s behavior through civil commitment, requiring reporting of pregnant women who use or are suspected of using alcohol to law enforcement and/or child welfare agencies, and initiating child welfare proceedings to remove children temporarily from or terminate parental rights of mothers who used alcohol during pregnancy.

In this paper, policies were coded as supportive were those that follow the categorization above and sought to promote and facilitate the use of services such as treatment that can help pregnant women reduce or stop their alcohol use or that prohibit criminal prosecutions for alcohol use during pregnancy. Accordingly, the following policies from the APIS Pregnancy and Alcohol set of topics were classified as supportive: mandatory warning signs, priority treatment, reporting requirement provisions that mandate reporting to gather epidemiological data or to refer women for assessment and treatment, and limitations on criminal prosecution. In contrast, the following policies were classified as punitive: civil commitment, child abuse/child neglect (particularly states defining alcohol exposure during pregnancy as child abuse or neglect); and reporting requirements provisions that pertain to referral of women who use or abuse alcohol during pregnancy to child welfare agencies.

As described above, laws addressing reporting requirements were subcategorized by those that require reporting for purposes of gathering data to assess the extent of the health problem or to refer a woman to treatment (supportive), and those that require reporting to refer the women to child welfare agencies (punitive). Because these two purposes are distinct and have different consequences, we distinguished between different purposes of reporting in this analysis. Specific exceptions were noted and were classified accordingly. For example, in relation to reporting requirements, one state (California) specifies that a positive toxicology test result at birth is not a sufficient basis for reporting child abuse or neglect, but may be used to assess child need for services (classified as supportive). Another state (Colorado) does not mandate reporting to child welfare or define prenatal exposure as child abuse but indicates that children may be taken into custody by law enforcement officers when newborns are identified by health providers as affected by substance abuse (classified as punitive).

Citation texts related to child abuse/neglect topics were reviewed and coded in three stages to identify laws that include language defining alcohol dependence or indicators of prenatal alcohol use (such as positive test for alcohol at birth, symptoms of FAS/FASD, or withdrawal symptoms) as child abuse or neglect, or defining the same as reportable as child abuse. First, provisional coding was conducted by one member of the research team who collected, organized, and reviewed the citation text. Second, the fourth author independently reviewed and coded text related to inclusion of alcohol dependence, alcohol abuse, or indicators of alcohol use as child abuse/neglect or as reportable as such. Third, ambiguities or differences in how to classify laws were reviewed and resolved by the first and fourth authors.

Finally, overall categorization of states in relation to punitive or supportive policies was defined as follows: (a) no alcohol and pregnancy-related policies; (b) predominantly punitive approaches; (c) predominantly supportive approaches; and (d) mixed approaches (including both supportive and punitive measures). State categorizations were developed by the first and fourth author, who came to a consensus on the categorization.

Results

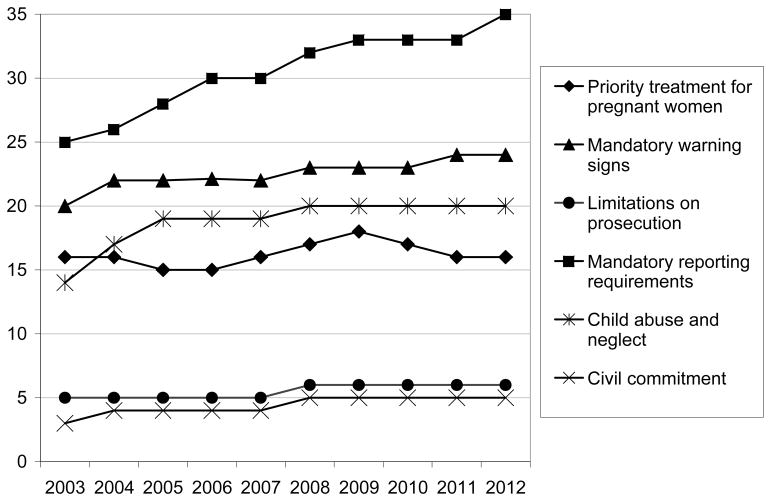

Figure 1 depicts trends over time in the number of states with policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy in the six policy areas outlined above, as of January 1 of each year. In general, policies explicitly addressing alcohol consumption during pregnancy increased between 2003 and 2012. The most common policy intervention, and the policy that evidenced the greatest increase (26 states in 2003 to 35 states in 2012) involved laws related to mandated reporting of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. State policies explicitly addressing alcohol use during pregnancy in relation to child welfare increased from 14 states in 2003 to 20 states in 2012. A small number of states also enacted new laws related to mandatory placement of warning signs about the potential harms of drinking during pregnancy (20 to 24 states). State law addressing specific provisions for priority treatment for pregnant women, postpartum women, and/or women with children (including whether priority treatment pertains to public and/or private treatment contexts), changed little (16, with some variation in interim years). States enacting laws limiting criminalization of prosecution of alcohol use during pregnancy remained low, but increased from five to six. Although laws allowing civil commitment of women to protect the fetus were relatively uncommon, five states had such provisions in 2012 (an increase from 3 in 2003).

Figure 1.

Number of states with policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy: Prevalence between January, 1, 2003 and January 1, 2012

Table 2 summarizes laws by the six APIS policy topics across the fifty states and the District of Columbia as of January 1, 2012. At that time, eight jurisdictions had no alcohol and pregnancy statutes. Nineteen jurisdictions had a predominately supportive approach to alcohol and pregnancy issues (mandatory warning signs, priority treatment, limitations on criminal prosecution, and reporting for surveillance and/or referral to treatment). Twelve jurisdictions had a singularly or predominately punitive approach to policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy (civil commitment, mandated referral to child welfare, and provisions defining alcohol exposure as child abuse or neglect). A majority of states with provisions specific to child welfare (15) have adopted a definition of child abuse and neglect that specifically includes alcohol dependence, alcohol abuse, and/or prenatal alcohol use (such as a positive test for alcohol at birth, symptoms of FAS/FAE, or withdrawal symptoms) or defines the same as reportable as child abuse or neglect. Of the six states adopting provisions specific to child welfare between 2003 and 2012, four adopted policies that defined alcohol dependence or prenatal alcohol use as child abuse or reportable as such. Notably, 12 jurisdictions across the nation had a mixed approach to alcohol and pregnancy policy with both supportive and punitive policies.

Table 2.

Policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy by state and the District of Columbia

| STATE | Mandatory Warning Signs | Civil Commitment | Limitations on Criminal Prosecution | Priority Treatment | Reporting Requirements | Child Abuse/Child Neglect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | X7 | |||||

| AK | X | X | X2,4 | |||

| AZ | X | X1 | X4 | X7 | ||

| AR | X1 | X4 | ||||

| CA | X | X | X2,3,5 | X5 | ||

| CO | X | X1, (d)3, 6 | X6 | |||

| CT | ||||||

| DE | X | X2 | ||||

| DC | X | X1 | X4 | |||

| FL | X2,3,4 | X7 | ||||

| GA | X | X1 | ||||

| HI | ||||||

| ID | ||||||

| IL | X | X1 | X2,3 | X | ||

| IN | X2,3,4 | X7 | ||||

| IA | ||||||

| KS | X | X | X2 | |||

| KY | X | X | X(d)2,(d)3,(d)4 | X7 | ||

| LA | X | X | X4 | X8 | ||

| ME | X3,4 | X | ||||

| MD | X1 | |||||

| MA | X4 | X | ||||

| MI | X2,4 | |||||

| MN | X | X | X3,4 | |||

| MS | ||||||

| MO | X | X | X1 | X2,(d)3,(d)4 | ||

| MT | ||||||

| NE | X | |||||

| NV | X | X | X4 | X | ||

| NH | X | |||||

| NJ | X | X2,3 | ||||

| NM | X | |||||

| NY | X | X3 | ||||

| NC | X | |||||

| ND | X | X7 | ||||

| OH | X2 | |||||

| OK | X | X1 | X2,4 | X7 | ||

| OR | X | X2,3 | ||||

| PA | X3,4 | |||||

| RI | X4 | X7 | ||||

| SC | X2 | X7 | ||||

| SD | X | X | X2,4 | X7 | ||

| TN | X | |||||

| TX | X | X2 | X7 | |||

| UT | X | X4 | X7 | |||

| VT | ||||||

| VA | X | X4 | X7 | |||

| WA | X | X | X2 | |||

| WV | X | X2 | ||||

| WI | X | X1 | X2,4 | X7 | ||

| WY |

NOTES

Also applies to private treatment

Discretionary rather than mandated reporting

Reporting purpose: for data gathering

Reporting purpose: for referral for assessment and/or treatment

Reporting purpose: referral to child welfare agency

Reporting to child welfare, provision clarifying positive toxicology at birth is not a sufficient basis for reporting child abuse or neglect, but may be used to assess child need for services. Assessment may trigger a report if mother is unable to provide regular care for child due to substance abuse.

Child may be taken into custody by law enforcement officer when newborn is identified by health providers as affected by substance abuse or demonstrating withdrawal resulting from prenatal drug exposure.

Definition of child abuse and neglect includes alcohol dependence, alcohol abuse, and/or prenatal alcohol use (such as positive test for alcohol at birth, symptoms of FAS/FAE, or withdrawal symptoms) or defines same as reportable as child abuse or neglect.

Allows physicians to order toxicology test to “determine whether there is evidence of prenatal neglect” in relation to illicit drugs. An amendment contingent on future funding includes “symptoms of withdrawal in the newborn or other observable and harmful effects in his or her physical appearance or functioning that a physician has cause to believe are due to the chronic or severe use of alcohol by the mother during pregnancy” as requiring a report to child welfare.

Discussion

This summary of state-level policies regarding alcohol use during pregnancy revealed substantial variation in characteristics of policies as of January 2012 (19 primarily supportive, 12 primarily punitive, 12 with a mixed approach, and eight with no policies). This study finds that mixtures of supportive and punitive policies relating to alcohol use during pregnancy are common – that, in fact, almost one fourth of states have “mixed” policy environments. The variability in policies pertaining to alcohol use during pregnancy is consistent with previous analyses of state policies relating to drug use during pregnancy, which have found considerable variability in the types and specific characteristics of policies across states (Drescher-Burke & Price, 2005; Ondersma et al., 2000). While the overall finding of variation is consistent between alcohol and drug-related policies, we note that distinguishing policies relating to alcohol from policies relating to drugs is important because some policies (such as warning signs) only apply to alcohol. In addition, policies and practices relating to reporting and child welfare policies have existed primarily for drugs and not for alcohol (Drescher-Burke & Price, 2005). However, this study found that the number of states with laws mandating reporting and laws addressing alcohol use during pregnancy in the context of child welfare law increased over the decade between 2003 and 2012, while laws in other policy areas have remained steady.

There is some disagreement as to whether reporting to CPS and removal of children by CPS is a form of punishing women (Ondersma et al., 2001); thus, some may disagree with our classification of child-welfare related policies. Some analyses of policies regarding alcohol and drug use during pregnancy characterize reporting to CPS and removal of children as a form of punishing women (Roberts, 1999; Thomas, Rickert, & Cannon, 2006). From this perspective, one of the harshest uses of child welfare policies occurs in states that treat positive toxicology screens or other evidence of prenatal alcohol or drug exposure alone as sufficient evidence of child abuse, neglect, or its equivalent (Schroedel & Fiber, 2001). Others do not view reporting to CPS and removal of children as punishment (Barth, 2001; Ondersma et al., 2000); instead, they view CPS reporting as a strategy to ensure the provision of early intervention services for infants and substance abuse treatment for women (Ondersma et al., 2000) and as a possible pathway to treatment and other services (Goodman & Wolff, 2013; Jacobson, Zellman, & Fair, 2003; Young et al., 2009).

Although direct comparison with policies related to substances other than alcohol was beyond the purview of the current study, other research has noted that public policies often differ based on whether substances are licit or illicit, with greater negative consequences attached to illicit drug use than alcohol use (Frohna & Lantz, 1999; Jacobson et al., 2003; Lester, Andreozzi, & Appiah, 2004). Policies classified in our study as punitive, such as mandated reporting as child abuse, and defining substance use during pregnancy or prenatal substance exposure as child abuse or neglect are more likely to be employed by states in response to illicit drug use than alcohol use (Jacobson et al. 2003; Lester et al., 2004). To our knowledge, these types of punitive policies have not been employed in relation to tobacco use during pregnancy.

Study Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, it is primarily descriptive and does not examine outcomes (intended or unintended) that may be associated with the policies described. Second, although it was possible to classify policies based on the criteria outlined in the methods section of the paper, it is not possible to characterize the degree to which implementation of policies aligns with the classifications of punitive, supportive, or mixed, nor to examine whether policies are implemented equitably across race/ethnicity and social class. For example, research has found evidence that Black women with newborns are more likely than White women with newborns to be reported to child welfare related to maternal alcohol or drug use during pregnancy (Roberts & Nuru-Jeter, 2012). Studies have also found differences in practices in referrals to child welfare on regional (urban vs. rural), organizational (e.g. different hospitals, public or private health care settings), and individual (e.g., child welfare staff with different attitudes) levels (Albert, Klein, Noble, Zahand, & Holtby, 2000; Drescher Burke, 2007; Ondersma, Halinka Malcoe, & Simpson, 2001). Third, because we focus on alcohol policy, findings do not designate states that only describe illicit drugs but not alcohol in child abuse and neglect statutes (e.g., identified in another study as including Maryland, Iowa, Oregon, Idaho, and Illinois) (Lester et al., 2004). In spite of these limitations, the article provides an overview of current policies, as well as policy trends, related to alcohol use during pregnancy.

Conclusions

Discussions of whether responses to prenatal alcohol and drug use are supportive or punitive have been occurring for at least the past twenty years (Barth, 2001; Chavkin, Wise, & Elman, 1998; Gomez, 1997; Lester et al., 2004; Ondersma et al., 2000; Potter, 2012; Roberts & Nuru-Jeter, 2010; Schroedel & Fiber, 2001). However, these discussions have generally neither focused on characterizing the current status of alcohol-related policies nor focused on evaluating their effects, with the exception of federally mandated warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers (Greenfield & Kaskutas, 1998; Kaskutas & Greenfield, 1992). While some research findings suggest that punitive policies may have negative consequences, many evidence-informed arguments about the potential effects of punitive policies (Roberts & Nuru-Jeter, 2010), there has been little rigorous empirical research on the effects of punitive policies or on the effects of mixed policy environments. Furthermore, although research has found that alcohol policies targeted at the general population (e.g. drinking age laws) appear to affect pregnancy outcomes (Zhang & Caine, 2011), studies to date have not examined explicitly the outcomes associated with policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy. Such evaluations might consider whether the policies have the intended negative consequences – i.e. leading women to enter treatment, cease alcohol use during pregnancy, and have improved birth outcomes. They may also consider whether the policies have unintended consequences, such as influencing women to avoid prenatal care out of fear of being punished; prenatal care avoidance could counteract improvements in women’s health and in birth outcomes. Considering both the intended and unintended consequences would help us appropriately characterize the net effect of such policies. The data presented in this paper set the stage for such evaluations.

This paper describes the status of U.S. state policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy as of January 1, 2012. Health care providers, social workers, and maternal and child health practitioners can use the classification of policies in their states to inform their clinical and systems-level strategies for caring for pregnant women who use alcohol, as well as to inform conversations about strengths and deficits in their state policies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Carol Pearce, MLIS, for assistance in research, cataloging, and analysis of state policies and Carol L. Canon, Research Scientist, The CDM Group, Inc. for contributions to early conceptualization of the manuscript. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism provided funding for a post-doctoral research fellowship that supported this study (T32 AA00724, L. Kaskutas, PI).

Contributor Information

LAURIE DRABBLE, Professor, San Jose State University Social Work, San Jose, California, USA

SUE THOMAS, Director, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Santa Cruz, California, USA

LISA O’CONNOR, Education Liaison, The National Center for Youth Law, Oakland, California, USA.

SARAH CM ROBERTS, Social Scientist, University of California, San Francisco - Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), San Francisco, California, USA.

References

- Albert V, Klein D, Noble A, Zhand E, Holtby S. Identifying substance abusing delivering women: Consequences for child maltreatment reports. Child abuse & neglect. 2000;24(2):173–183. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht J, Lindsay B, Terplan M. Effect of waiting time on substance abuse treatment completion in pregnant women. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2011;41(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee opinion no. 473: substance abuse reporting and pregnancy: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011a;117(1):200–201. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820a621600006250-201101000-00037. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 496: At-risk drinking and alcohol dependence: Obstetric and gynecologic implications. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011b;118:383–388. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820a621600006250-201101000-00037. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony EK, Austin MJ, Cormier DR. Early detection of prenatal substance exposure and the role of child welfare. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(1):6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP. Research outcomes of prenatal substance exposure and the need to review policies and procedures regarding child abuse reporting. Child Welfare. 2001;80(2):275–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W, Breitbart V, Elman D, Wise P. National survey of the states: Policies and practices regarding drug-using pregnant women. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(1):117–119. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W, Wise PH, Elman D. Policies towards pregnancy and addiction. Sticks without carrots. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;846:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailard C, Nash E. State responses to substance abuse among pregnant women. The Guttmacher report on public policy. 2000;3(6):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher-Burke K, Price A. Identifying, reporting, and responding to substance exposed newborns: An exploratory study of policies and practices. Berkeley, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher Burke K. Substance-exposed newborns: Hospital and child protection responses. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29(12):1503–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Ethen M, Ramadhani T, Scheuerle A, Canfield M, Wyszynski D, Druschel C. Alcohol consumption by women before and during pregnancy. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2009;13(2):274–285. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figdor E, Kaeser L. Concerns mount over punitive approaches to substance abuse among pregnant women. The Guttmacher report on public policy. 1998;1(5):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman DJ, Wolff KB. Screening for substance abuse in women’s health: A public health imperative. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2013;58(3):278–287. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Kaskutas LA. Five years’ exposure to alcohol warning label messages and their impacts: Evidence from diffusion analysis. Applied Behavioral Science Review. 1998;6(1):39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE. From generic to gender-responsive treatment: changes in social policies, treatment services, and outcomes of women in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(sup5):327–343. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. Substance abuse during pregnancy. State Policies in Brief. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_SADP.pdf.

- Guttmacher Institute. State Policies in Brief: Substance Abuse During Pregnancy. 2011 http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_SADP.pdfRetrieved February 11, 2011.

- Jacobson PD, Zellman GL, Fair CC. Reciprocal obligations: Managing policy responses to prenatal substance exposure. Milbank Quarterly. 2003;81(3):475–497. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HA. Comparative analysis of state statutes: Reporting, assessing, and intervening with prenatal substance abuse. The Social Policy Journal. 2003;2(4):71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas L, Greenfield TK. First effects of warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1992;31(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(92)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA. Interpretations of risk: The use of scientific information in the development of the alcohol warning label policy. Substance Use & Misuse. 1995;30(12):1519–1548. doi: 10.3109/10826089509104416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Andreozzi L, Appiah L. Substance use during pregnancy: Time for policy to catch up with research. Harm Reduction Journal. 2004;1(5):44. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-1-5. Retrieved from http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/1/1/5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Rosenbaum M. Pregnant women on drugs : combating stereotypes and stigma. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism APIS. Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) Pregnancy and Alcohol. nd-a Retrieved July 15, 2013, from http://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/APIS_Policy_Topics.html.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) Pregnancy and Alcohol: Priority Treatment. nd-b Retrieved July 15 2013 from http://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/Alcohol_and_Pregnancy_Priority_Treatment.html.

- O’leary CM, Bower C. Guidelines for pregnancy: What’s an acceptable risk, and how is the evidence (finally) shaping up? Drug and alcohol review. 2012;31(2):170–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Halinka Malcoe L, Simpson SM. Child protective services’ response to prenatal drug exposure: Results from a nationwide survey. Child abuse & neglect. 2001;25(5):657–668. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Simpson SM, Brestan EV, Ward M. Prenatal drug exposure and social policy: The search for an appropriate response. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(2):93–108. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VWV, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA)-a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2011;118(12):1411–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter DA. Drawing the line at drinking for two: Governmentality, biopolitics, and risk in state legislation on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Advances in Medical Sociology. 2012;14:129–153. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DE. Killing the black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. New York, Vintage: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, Nuru-Jeter A. Universal screening for alcohol and drug use and racial disparities in child protective services reporting. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012;39(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SC, Nuru-Jeter A. Women’s perspectives on screening for alcohol and drug use in prenatal care. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(3):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SC, Pies C. Complex calculations: How drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2010;15:333–341. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0594-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroedel JR, Fiber P. Punitive versus public health oriented responses to drug use by pregnant women. Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics. 2001;1(1):Article 15. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjhple/vol1/iss1/15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Rickert L, Cannon C. The meaning, status, and future of reproductive autonomy: The case of alcohol use during pregnancy. UCLA Women’s LJ. 2006;15(1) [Google Scholar]

- Tremper C, Thomas S, Wagenaar AC. Measuring law for evaluation research. Evaluation review. 2010;34(3):242–266. doi: 10.1177/0193841X10370018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KR, Hewitt BG. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: When science, medicine, public policy, and laws collide. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2009;15(3):170–175. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KR, Hewitt BG, Thomas JD. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Research challenges and opportunities. Alcohol Research and Health. 2011;34(1):4–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Kristjanson AF, Wilsnack SC, Crosby RD. Are U.S. women drinking less (or more)? Historical and aging trends. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:341–348. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NK, Gardner S, Otero C, Dennis K, Chang R, Earle K. Substance-exposed infants: State responses to the problem. Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Caine E. Alcohol policy, social context, and infant health: The impact of minimum legal drinking age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011;8(9):3796–3809. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8093796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]