Abstract

Ovarian reserve and its utilization, over a reproductive life span, are determined by genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. The establishment of the primordial follicle pool and the rate of primordial follicle activation have been under intense study to determine genetic factors that affect reproductive lifespan. Much has been learned from transgenic animal models about the developmental origins of the primordial follicle pool and mechanisms that lead to primordial follicle activation, folliculogenesis, and the maturation of a single oocyte with each menstrual cycle. Recent genome-wide association studies on the age of human menopause have identified approximately 20 loci, and shown the importance of factors involved in double-strand break repair and immunology. Studies to date from animal models and humans show that many genes determine ovarian aging, and that there is no single dominant allele yet responsible for depletion of the ovarian reserve. Personalized genomic approaches will need to take into account the high degree of genetic heterogeneity, family pedigree, and functional data of the genes critical at various stages of ovarian development to predict women's reproductive life span.

Keywords: ovarian reserve, menopause, premature ovarian failure

Women are delaying childbearing due to the pressures of money, education, and the desire to succeed in their careers. This revolution has caused a shift in childbearing years from the early 20s to the mid- to late-20s with approximately one-third of first time mothers in the United States and Canada being in their 30s.1,2 The ability to determine a woman's ovarian reserve may influence her decisions related to family goals. Available monitoring mechanisms, such as ultrasound to visualize and quantitate antral follicles and serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), are superior to measuring follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, but are unable to establish the reproductive potential of remaining follicles in the ovary.3,4 Additional biomarkers are greatly needed to identify women at risk for ovarian failure, and to identify women who can benefit from advanced fertility preservation technologies prior to oocyte loss. There is currently no reliable genetic biomarker(s) of ovarian reserves that can be used as a screening/diagnostic tool.

The numbers of primordial follicles that have the potential to mature into a fertilizable oocyte are one component of the ovarian reserve. The finite pool of primordial follicles is established during early development, by the initial colonization of the ovary and primordial germ cells. This process has been reviewed extensively.5,6 In brief, primordial germ cells migrate from the extra-embryonic mesoderm (embryonic day 7.5 [E7.5] in the mouse, whose length of gestation is ~18–19 days; 5th week of gestation in human), through the hindgut and dorsal mesentery, eventually colonizing the genital ridge. Proliferation of primordial germ cells occurs during migration and persists until E13.5 in the mouse and the 10th week of gestation in human. Primordial germ cells are maintained as clusters of two or more oocytes and initiate meiosis approximately at the 10th gestational week in the human (E13.5 in mouse), and arrest in the diplotene stage of meiosis I (E18.5 in mouse; before the 20th week of gestation in humans). With meiosis arrest, the oocyte clusters break down to form primordial follicles, characterized by small oocytes enveloped by a single layer of flat pregranulosa cells. Oocyte cluster breakdown is accompanied by a considerable loss of germ cells (from 75,000 at peak to 15,000 at birth in mouse models7; from 7 106 follicles at the 20th week of gestation to ~1 106 follicles at birth in humans8). It is unclear why so many germ cells are lost during the formation of the primordial follicle pool. Once formed, primordial follicles are recruited throughout life to enter folliculogenesis, eventually resuming meiosis and releasing a mature egg at ovulation.9 The ovarian reserve can be affected at multiple points during development and folliculogenesis: (1) primor-dial germ cell migration and proliferation; (2) oocyte entry into meiosis I, synapsis, recombination, and arrest in dictyate stage; (3) transition from oocyte clusters to primordial follicles; (4) primordial follicle activation; and (5) defects in folliculogenesis or ovulation. The first three stages occur prior to birth and therefore are not likely to be relevant in clinical treatment of infertility. The current and long-held dogma has been that the number of primordial follicles at birth represents the total ovarian reserve for the entire span of reproductive life; however, contradictory data suggest that oocyte “stem cells” continuously contribute to the ovarian reserve.10 The existence of oogonial stem cells, and whether such stem cells are physiologically relevant and/or functional, is controversial, and will not be discussed further, but has the potential to transform the field of reproductive medicine.11

Menopause is the culmination of the gradual loss of ovarian follicles that occurs over the years, a natural consequence of ovarian follicle depletion that happens most often in the 5th decade of life. Pathogenic depletion of follicles, premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), is defined as loss of ovarian function prior to 40 years of age. Women with POI present with elevated levels of FSH, low levels of AMH, and decreased estrogen concentrations.12 Both menopause and POI are due to depleted ovarian reserve and loss of normal ovarian function and thus may share common genetic origins. Genetics is an important determinant of menopause and POI. For example, age at menopause is highly heritable (41–63%) between sisters and mother–daughter pairs.13–16 Genetic syndromes that accelerate aging in general associate with premature ovarian failure and include Fanconi anemia (FANCA), Werner syndrome (WRN), Bloom syndrome (BLM), and Ataxia telangiectasia mutated syndrome (ATM), among others.17 Fragile X premutation and X chromosome genomic imbalances associate with POI. These and other examples indicate the importance of genetics in the establishment and maintenance of ovarian reserves. We will focus here on genes known to affect ovarian reserve and research implications for diagnostics and future work.

Genes Involved in Primordial Follicle Activation and Folliculogenesis

The transition from primordial to primary follicle involves oocyte growth, granulosa cell differentiation from flat to cuboidal, and theca cell recruitment. It is very difficult to study primordial follicle formation and activation in humans, and animal models have been essential to better understand the genetics of folliculogenesis. Moreover, studies in animal models have provided a plethora of candidate genes for ovarian failure. Of the identified genes, a subset is mutated in patients with POI, thus providing relevance of animal models to human disease. Studies in early folliculogenesis have also revealed expression of unique, oocyte-specific transcriptional regulators that regulate genes essential for oocyte growth as well as early embryogenesis. Early folliculo-genesis is a critical event in determining oocyte and embryo quality.

Factor in the germline α (Fig1a) is an essential transcription factor for primordial follicle formation in mice. Figla was one of the first transcriptional regulators discovered to be essential for primordial follicle formation. Figla is a basic helix-loop-helix transcriptional regulator, specifically expressed within oocytes of primordial and more advanced follicle types. Figla knockout mice have normal primordial germ cell migration and proliferation but fail to produce primordial follicles and lose all oocytes shortly after birth18 (Fig. 1A). Therefore, Figla must be essential prior to primordial follicle formation. Figla directly regulates expression of zona pellucida glycoproteins 1, 2, and 3 (Zp1, Zp2, and Zp3, respectively), and may function cooperatively with LIM homeobox 8 (Lhx8) to regulate the expression of Zp1 and Zp3. ZP1–3 are necessary for the proper formation of the zona pellucida. The human homolog of FIGLA is also expressed in oocytes of human primordial follicles, forms heterodimers with the Tcf3 protein, and binds to the E-box of the human ZP2 promoter.19–21 Human FIGLA is expressed as early as 14 weeks of gestational age with a dramatic increase in transcripts by midgestation, suggesting a similarly conserved function of the human and mouse FIGLA proteins. Heterozygous mutations in FIGLA were found to be present in women with POI20 (Table 1). Thus, haploinsufficiency of FIGLA likely causes accelerated loss of ovarian reserves in humans.

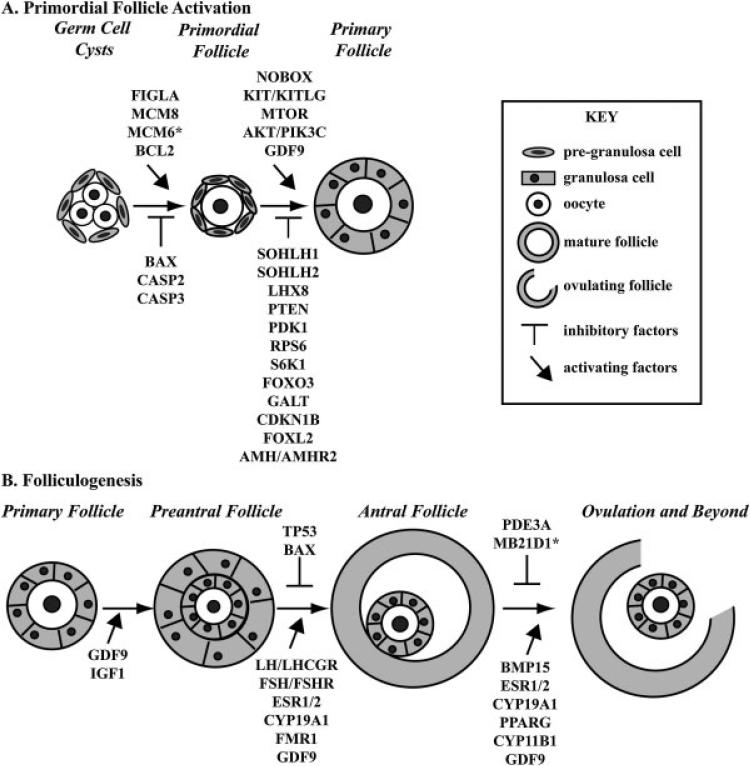

Figure 1.

Genes Essential for Preservation of Ovarian Reserve. (A) Primordial follicle activation to develop to primary follicles requires a delicate balance of both promoting and inhibiting factors. The transition from germ cell cysts to primordial follicles requires stimulatory signals from Figla, Mcm8, Mcm6, and Bcl2. Bax, Casp2, and Casp3 can all inhibit this initial transition to primordial follicles. The decision to become a primary follicle requires action from Nobox, Kit/Kitl, Mtor, GDF9, and Akt1/Pik3c signaling. Alternatively, SOHLH1, SOHLH2, LHX8, Pten, Pdk1, Rps6, S6K1, Foxo3, Galt, Cdkn1b, Foxl2, and Amh/Amhr2 function to prevent premature activation of the primordial follicle. (B) Folliculogenesis beyond the primary follicle also requires orchestration of multiple protein factors. The transition from primary to preantral follicles requires the action of Gdf9 and Igf1 and communication of the oocyte with supporting cells. The transition from early preantral follicles to antral follicles requires hormonal control, through Lh/Lhcgr, Fsh/Fshr, Esr1, and ESR2. Additionally, the action of Cyp19a1, GDF9, and Fmr1 are essential for antral follicle formation while Tp53 and Bax may inhibit this activation. Beyond antral follicle formation, release of the oocyte at ovulation requires activation by Bmp15, Esr1/2, Cyp19a1, Pparg, and Cyp11b1. Pde3a and Mb21d1 can prevent ovulation by maintaining oocyte arrest. Function implied based on association but not directly studied in ovarian physiology.

Table 1.

Genes associated with idiopathic premature ovarian failure in humans

| Gene | Locus | Sequence mutation | Protein mutation | dbSNP | Cohort ethnicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP15 | Xp11.22 | c.242A > G | p.H81R | Caucasian | 75 | |

| c.595G > A | p.G199R | Caucasian | 75 | |||

| c.13A > C | Tunisian | 76 | ||||

| p.L148P | European (French/African) | 71 | ||||

| c.202C > T | p.R68W | Caucasian | 77 | |||

| c.538G > A | p.A180T | Caucasian | 77 | |||

| c.704A > G | p.Y235C | Caucasian | 77 | |||

| CDKN1B | 12p13.2 | c.356T > C | p.I119T | Tunisian | 60 | |

| CYP19A1 | 15q21.2 | rs6493489 | Korean | 100,101 | ||

| rs6493488 | Korean | 100,101 | ||||

| rs10046 | Korean | 100,101 | ||||

| ESR1 | 6q25.1 | c. – 397T < C | rs2234693 | Chinese, Brazilian, European (Swiss) | 102,109,110 | |

| c. – 351A > G | rs1569788 | Korean | 101,108 | |||

| FIGLA | 2p13.3 | c.419–21 delACA | p.140 delN | rs99307024 | Chinese | 20 |

| FOXL2 | 3q22.3 | p.G187D | Tunisian | 82 | ||

| c.738C > T | Indian | 83 | ||||

| c.773C > G | Indian | 83 | ||||

| c.898–927del | European (Italian) | 84 | ||||

| c.1009T > A | European (Italian) | 84 | ||||

| c.A221_A230del | Slovenian | 85 | ||||

| c.772(1009)T > A | New Zealand | 85 | ||||

| FOXO3 | 6q21 | c.280C > T | p.L94F | Mixed | 61 | |

| c.1021G > A | p.A341T | Mixed | 61 | |||

| c.1156C > T | p.L386F | Mixed | 61 | |||

| FSHR | 2p16.3 | c.566C > T | p.A189V | European (Finnish) | 90 | |

| c.1255G > A | p.A419T | European (Finnish) | 92 | |||

| c.1723C > T | p.A575V | Indian | 93 | |||

| c.-29G > A | Indian | 93 | ||||

| GDF9 | 5q31.1 | c.712A > G | p.T238A | Chinese | 70 | |

| c.646G > A | p.V216M | Indian | 69 | |||

| c.199A > C | p.L67E | Indian | 69 | |||

| c.307C > T | p.P103S | Caucasian | 72 | |||

| p.S186Y | Caucasian | 71 | ||||

| INHA | 2q35 | c.–16C > T | New Zealand | 107 | ||

| c.–124A > G | Slovenian | 107 | ||||

| NOBOX | 7q35 | c.1064G > A | p.R355H | Caucasian | 33 | |

| c.1079G > A | p.R360Q | Caucasian | 33 | |||

| c.907C > T | p.R303X | European (French) | 34 | |||

| c.271G > T | p.G91W | European (French) | 34 | |||

| c.349C > T | p.R117W | European (French) | 34 | |||

| c.1025G > C | p.S342T | European (French) | 34 | |||

| c.1048G > T | p.V350L | European (French) | 34 | |||

| POU5FI | 6q21.33 | c.37C > A | p.P13T | Chinese | 37 | |

Spermatogenesis and oogenesis helix-loop-helix 1 and 2 (Sohlh1 and Sohlh2) and Lhx8 repress primordial follicle activation. Sohlh1 and Sohlh2 are germ cell–specific transcription factors expressed within oocytes of germ cell cysts, primordial and primary follicles, but not the granulosa cells.22Sohlh1 and Sohlh2 repress primordial follicle activation, as loss of either gene causes rapid primordial follicle activation and follicle death with subsequent ovarian failure (Fig. 1A). SOHLH1 is able to induce expression of oocyte-specific genes, including Zp1 and Zp3, but not Zp2.23 Sohlh1 and Sohlh2 regulate c-kit (Kit) and growth differentiation factor 9 (Gdf9) gene expression, two factors that are involved in the differentiation of granulosa cells during folliculogenesis.22,24Sohlh1 and Sohlh2 regulate two other transcriptional regulators, Lhx8 and newborn ovary homeobox (Nobox).22Lhx8 is a transcriptional regulator, preferentially expressed in oocytes of germ cell cysts, primordial, primary, and antral follicles.22 Moreover, SOHLH1 can bind to E-box elements, bound by helix-loop-helix transcriptional regulators, in the Lhx8 promoter, suggesting that SOHLH1 directly regulates Lhx8 expression. Loss of Lhx8 results in decreased numbers of primordial follicles without affecting meiosis25 (Fig. 1A). LHX8 contributes to transcriptional activation of multiple genes essential for oocyte maturation, including but not limited to Gdf9, Zp1, Zp3, POU class 5 homeobox 1 (Pou5f1), 2′–5′ oligoadenylate synthetase 1D (Oas1d), and NLR family, pyrin domain containing 4C (Nlrp4c).25 Many of these genes are also regulated by Sohlh1 and Sohlh2. Lhx8 can induce the expression of B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) associated X protein (Bax) and caspase 2 and 3, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidases (Casp2 and Casp3). BAX and caspases are thought to be involved in follicular atresia, suggesting that Lhx8 may function as a switch to select which primordial follicles survive and which die.25 Genetic variants in SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 have not been evaluated in relation to POI or menopause. Genetic variants in LHX8 exons were evaluated in a small population of Caucasian women, but no mutations were identified in LHX8 exons in this population.26

NOBOX promotes primordial follicle activation. Nobox is a conserved homeodomain transcriptional regulator that is exclusively expressed in the oocytes but not in the surround ing pregranulosa cells.27 Nobox has been shown to promote oocyte and follicle growth beyond the primordial follicle stage.28 Germ cell cyst breakdown and oocyte separation is impeded in Nobox knockout mice and loss of Nobox leads to an accelerated loss of oocytes28,29 (Fig. 1A). Nobox expression is regulated by Lhx825 and Sohlh1.22 Microarray analysis of whole ovaries from wild type and Nobox knockout newborn ovaries revealed 33 oocyte-specific genes that were up- or downregulated by at least fivefold compared with wildtype.30 Genes involved in pluripotency, Pou5f1 and Sal-like protein 4 (Sall4), were found to be downregulated in knockout ovaries and have been shown to be direct transcriptional targets of Nobox.30,31 Multiple signaling pathways have also been shown to be downregulated in Nobox knockout mice, including direct targets, Gdf9, aspartate aminotransferase (Ast1), and oocyte secreted protein 1 (Oosp1), and indirect targets jagged 1 (Jag1), fetuin B (Fetub), and R-spondin 2 (Rspo2).30 Genes involved in apoptosis and inflammation were also found to be downregulated in knockout mice, including genes of the NLR family, pyrin domain (Nlrp) and 2′–5′-oligoadeny-late synthase (Oas) families, which may protect the oocyte reserve from being depleted due to inflammation induced cell death.30 Moreover, NOBOX regulates expression of genes necessary for early, postfertilization events (maternal effect genes), such as zygote arrest protein 1 (Zar1) and DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1). These results show the importance of early folliculogenesis in specifying oogenesis and early embryo development.

Human NOBOX expression within the ovary is oocyte specific, and observed from the primordial follicle to the metaphase II (MII) oocyte.32NOBOX mutations were identi-fied in a population of Caucasian women with POI (Table 1). Two of the eleven genetic variants were found to cause missense mutations (p.R355H and p.R360Q) in the homeo-domain portion of the protein. The homeodomain portion of NOBOX binds DNA and likely plays an important role in the transcriptional control of target genes. The p.R355H mutation disrupted the binding of the NOBOX homeodomain to the NOBOX consensus DNA-binding element.33 Other groups have also shown association of NOBOX mutations with human POI34–36 (Table 1). A non-synonymous mutation (p. P13T) in POU5F1, a downstream effector of NOBOX, was identified in at least one POI patient in a cohort of Chinese women with POI.37 Nobox and its downstream targets are essential for oocyte-specific gene expression and induction of primordial follicle activation, and likely carry out similar functions in humans.

Oocyte expressed Kit tyrosine kinase receptor (KIT) responds to granulosa cell secreted Kit ligand (KITL). Pregranulosa cells secrete Kitl under stimulation of leukemia inhibitory factor (Lif).38 Lhx8, Sohlh1, and Sohlh2 upregulate Kit expression, as deficiency in these transcriptional regulators cause a severe downregulation in Kit expression. SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 directly bind to the Kit promoter39 (Fig. 1A). Many naturally occurring mutations in Kit, as well as Kitl, have been characterized and can affect various stages of primordial germ cell migration, proliferation, and survival.40–42 One of these mutations is a point mutation in Kit, results in disruption of the conserved adenosine triphosphate binding domain of tyrosine kinase, and causes POI in mice.43 Female mice have fewer germ cells at birth and premature depletion of primor-dial follicles by 2 months after birth.43 These mice also display symptoms shared with menopausal women and POI patients, including elevated FSH, decreased bone density, and enlarged hearts with reduced cardiac function. Among a limited number of women with POI, KITL mutations are uncommon44 while little is known with regard to KIT mutations and POI.

Activation of thymoma viral proto-oncogene 1 (Akt1)/ phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PIK3C) signaling potentiates primordial follicle activation. Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is a negative regulator of Pik3c activity and thus can slow down primordial follicle activation45,46 (Fig. 1A). KIT has been an attractive tyrosine kinase receptor for the activation of PIK3C in the oocyte; however, current data do not support its role in primordial follicle activation. Mice with a knock-in mutation of KIT, which completely eliminates signaling via PIK3C, demonstrated primordial follicle activation and were fertile; however, primordial follicle depletion in these mice was accelerated.47 Primordial follicle activation can be stimulated through the Akt1 activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (Mtor) and its downstream targets, ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6k1), ribosomal protein S6 (Rps6), and 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (Pdk1)48,49 (Fig. 1A). Indeed, premature activation of primordial follicles is seen in knockout mice lacking Pten,46Pdk1,50 and Rps650 (Fig. 1A). This pathway is an attractive model for pharmacologic intervention as inhibitors of Mtor and Pten already exist.49 Rapamycin, a known inhibitor of Mtor, can impede the ability of Mtor to promote primordial follicle activation.51 Conversely, the use of Pten inhibitor, bpV(HOpic), can activate primordial follicles.52 Pharmaceutical manipulation of this pathway could be harnessed to promote follicle activation in infertile women with diminishing ovarian reserve and gonadotropin resistance, and for cancer patients with cryopreserved ovaries.11 However, the ubiquitous importance of this pathway to many tissues is an obstacle for the design of ovary-specific interventions. SNPs in PTEN have not been associated with POI in Chinese or Japanese women.53,54

Forkhead box O3 (FOXO3), a transcription factor, is an important oocyte-specific regulator of primordial follicle activation. Foxo3 knockout mice are sterile by 15 weeks of age due to premature activation of primordial follicles, resulting in loss of the entire ovarian reserve55 (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that Foxo3 represses primordial follicle activation and its absence leads to widespread activation. Foxo3 is possibly a terminal target of Akt1. Akt1 phosphorylation of Foxo3 induces translocation of FOXO3 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and this shuttling is associated with primordial follicle activation.45 Mice lacking Pten, a negative regulator of Akt1, have elevated Foxo3 phosphorylation, primordial follicle activation, and phenocopy Foxo3 knockout mice.45,55 Foxo3 inhibition of primordial follicle activation is proposed to occur through the indirect control of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (Cdkn1b; Fig. 1A). Cdkn1b has been shown to increase during folliculogenesis and is absent in oocytes.56 Loss of Cdkn1b results in premature primordial follicle activation.57 It has been proposed that Cdkn1b, in granulosa cells, and Foxo3, in oocytes, function synergistically to maintain the primordial follicle pool and thus the ovarian reserve.56 Interestingly, Foxo3 was found to act upstream of galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (Galt),58 which encodes an enzyme essential for galactose metabolism. Under negative control by the prolactin receptor, Foxo3 and Galt may function to prevent primordial follicle recruitment58 (Fig. 1A). GALT deficiency causes galactosemia and the majority of women with galactosemia will suffer from POI.8,58 In patients with nonsyndromic POI of Chinese descent, PTEN and CDKN1B variants were not found to be a common cause of POI, as all variants identified were also present in controls.59 A single variant in CDKN1B (c.356T > C) was found in one POI patient with primary amenorrhea out of 43 total POI patients of Tunisian descent60 (Table 1). Three heterozygous missense mutations in FOXO3 were identified in women with POI but none were shown to result in a significant reduction in FOXO3 activity61 (Table 1).

Failure of oocytes to resume meiosis impairs their ability to properly develop. Oocytes are arrested in meiotic prophase I during embryonic development, and meiosis does not resume until a preovulatory follicle (Graafian follicle) receives a luteinizing hormone (LH) surge to induce ovulation7 (Fig. 1B). The follicular milieu maintains meiotic arrest until the time of ovulation primarily through the maintenance of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), also in the milieu, facilitates maintenance of oocyte arrest through inhibition of phosphodiesterase 3A (Pde3a).62 PDE3A normally causes the depletion of cAMP, and levels of cGMP in the follicle can protect the level of cAMP; thus, cAMP is available to maintain prophase I arrest via protein kinase A phosphorylation of WEE1 homolog 2 (WEE2).62 The LH surge, to induce ovulation, causes a decrease in cGMP and thus downstream loss of cAMP, allowing meiosis to proceed.62 Although these proteins and cAMP/ cGMP signaling have not been directly evaluated in POI or menopause, a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified SNPs in Mab-21 domain containing 1 (MB21D1), a cGMP synthetase, in the age at onset of menopause63 (Table 2). Thus, loss in cGMP levels could lead to a loss in maintenance of meiotic arrest (Fig. 1B). Mb21d1 expression in mice is not unique to the ovary, but it is highly enriched in oocytes. The functional role of Mb21d1 in folliculogenesis has not been examined to date.

Table 2.

GWAS loci associated with age at menopause

| Locus | Gene | Protein mutation | dbSNP | Cohort ethnicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1q43 | EXO1 | rs1635501 | Mixed | 117 | |

| 2p16.3 | LHCGR | rs4953616 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| rs6729809 | Caucasian | 96 | |||

| rs7579411 | Caucasian | 96 | |||

| rs4374421 | Caucasian | 96 | |||

| 2p23.3 | EIF2B4 | rs7586601 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 2p22.2 | CYP1B1 | p.N453S | European (Austrian) | 178 | |

| p.R48G | rs10012 | Chinese | 177 | ||

| p.A119S | rs1056827 | Chinese | 177 | ||

| p.L432V | rs1056836 | Chinese | 177 | ||

| 2q21.3 | MCM6 | rs2164210 | European | 63 | |

| 2q31.1 | TLK1 | rs10183486 | Mixed | 117 | |

| 3p25.2 | PPARG | p.P12A | rs1801282 | Korean | 174 |

| rs2120825 | Korean | 174 | |||

| Silent | rs3856806 | Korean | 174 | ||

| rs4135280 | Caucasian | 96 | |||

| 4q21.23 | HELQ | rs4693089 | Mixed | 117 | |

| 5p15.31 | SRD5A1 | rs494958 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 5q13.3 | COL4A3BP | rs181686584 | African American | 97 | |

| 5q15 | PCSK1 | rs271924 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 5q32.2 | UIMC1 | Silent | rs365132 | Chinese; European American; African American; Mixed | 116,117,158,160 |

| rs402511 | American | 160 | |||

| rs601923 | Hispanic | 159 | |||

| rs7718874 | American | 160 | |||

| 5q35.2 | HK3 | rs2278493 | Chinese | 102 | |

| rs691141 | American | 160 | |||

| 6p21.33 | PRRC2A/BAT2 | p.R1740H | rs1046089 | Mixed | 117 |

| TNF | rs909253 | Caucasian | 96 | ||

| 6p24.2 | SYCP2L | rs2153157 | European American; American Indian; Mixed | 117,158,160 | |

| 6q13 | MB21D1/ C6orf150 | p.K625E | rs311686 | European | 63 |

| 6q25.1 | ESR1 | rs2234693 | Chinese | 102 | |

| 6q25.3 | IGF2R | rs9457827 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 7q21.3 | SLC25A13 | rs2375044 | European | 63 | |

| 8q21.3 | NBN | rs2697679 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 9p13.3 | AMH | p.S49I | rs10407022 | European (Dutch) | 86 |

| 9q22.33 | TGFBR1 | rs1590 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 11p14.1 | rs12294104 | Mixed | 117 | ||

| FSHB | rs11031010 | Caucasian; African American | 96,97 | ||

| rs621686 | Caucasian | 96 | |||

| rs7951733 | Caucasian | 96 | |||

| 11p15.5 | KCNQ1 | rs79972789 | African American | 97 | |

| 11q22.1 | PGR | rs619487 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 11q23.1 | ANKK1 | rs6279 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 12q13.3 | PRIM1 | rs2277339 | Mixed | 117 | |

| 12q13.13 | AMHR2 | rs11170547 | European (Dutch) | 80,86 | |

| 12q23.2 | IGF1 | rs1019731 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 15q21.2 | CYP19A1 | rs11856927 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 15q26.1 | FANCI | rs2307449 | Mixed | 117 | |

| 16p13.13 | rs10852344 | Mixed | 117 | ||

| 17q21.31 | CRHR1 | rs4640231 | European | 63 | |

| 17q23.3 | POLG | rs2307449 | Chinese; Mixed | 116,117 | |

| 18q21.1 | SMAD7 | rs4939833 | Caucasian | 96 | |

| 19p13.2 | LDLR | rs189596789 | African American | 97 | |

| 19q13.32 | APOE | p.C130R | rs429358 | Chinese | 185 |

| p.R176C | rs7412 | Chinese | 185 | ||

| rs769450 | African American; Caucasian | 97,186 | |||

| 19q13.42 | BRSK1/TMEM150B | rs1172822 | American | 160 | |

| rs12611091 | Chinese | 102,116 | |||

| rs17782355 | Hispanic | 159 | |||

| rs2384687 | American | 160 | |||

| p.L199F | rs7246479 | American, Chinese | 116,160 | ||

| rs897798 | American, African American | 97,160 | |||

| rs11668344 | Mixed | 117 | |||

| rs1172822 | Chinese; European American | 116,158 | |||

| 19q13.42–13.43 | NLRP11 | p.P438L | rs12461110 | Chinese; Mixed | 116,117 |

| 20p12.3 | MCM8 | p.E341K | rs16991615 | European American; Hispanic; American Indian; Caucasian | 117,155,158–160 |

| rs236114 | Hispanic | 159 | |||

| Xp11.22 | BMP15 | rs6521896 | European (Dutch) | 80 | |

Bcl2 and Bax conversely regulate follicular atresia. How oocytes are selected to proceed through folliculogenesis or to die by atresia is unknown. Many oocytes are lost during the transition from primordial to primary follicles. Two genes, Bcl2 and Bax, involved in apoptosis have been shown to play a role in the selection of oocytes. Bcl2 works to protect against apoptosis, while Bax promotes cell death48 (Fig. 1A). Oocyte and primordial follicle numbers are decreased in Bcl2 knockout mice. However, advanced preantral and antral follicle numbers do not differ when compared with wild-type controls. This suggests that Bcl2 has a role in maintaining the ovarian reserve, but not the progression of folliculogenesis. In contrast, Bax knockout mice have an extended reproductive lifespan due to a decrease in the number of atretic follicles.64,65 Therefore, Bax may contribute to selection of granulosa cells which undergo follicular atresia.64 Variants in BCL2 and BAX have not been evaluated in human populations with POI or in relation to menopausal age.

Gdf9 and bone morphogenic protein 15 (Bmp15) are oocyte-secreted growth factors that affect granulosa cell differentiation function. Gdf9, expressed in primordial and primary follicles, is critical for early folliculogenesis and is expressed through ovulation48 (Fig. 1A, B). Gdf9 is essential for granulosa cell proliferation, theca cell differentiation, and proper steroid production. Gdf9 can also regulate Kitl and inhibin α (Inha) expression within the granulosa cells.48 Global knockout of Gdf9 in mice shows an inhibition in folliculogenesis at the primary follicle stage.66 Another oocyte secreted factor, Bmp15, is essential for preantral follicle development in sheep,67 but not in mice,68 showing species or mutation-specific differences (Fig. 1B). Mice lacking Bmp15 have normal folliculogenesis and subfertility due to impaired ovulation and fertilization.68 Three missense mutations in GDF9 were found in POI patients of Chinese or Indian descent69,70 (Table 1). Two additional mutations were present in Caucasian women with POI (p.P103S and p. S186Y)71,72; however, no variants were identified in Japanese women with POI.73BMP15 was evaluated for etiology of POI in multiple ethnicities. Several novel variants were found in BMP15 in all populations evaluated71,74–77except in women with POI of Chinese or New Zealand descent78,79 (Table 1). Similarly, a SNP in BMP15 (rs6521896) is associated with age at menopause in a European population80 (Table 2). However, the functional data on these SNPs are lacking in many of the studies.

Forkhead box L2 (Foxl2), a transcriptional regulator, can repress primordial follicle activation through upregulation of Amh. Foxl2 activates the expression of Amh in granulosa cells of developing follicles, which, when secreted, can act in a paracrine manner to repress primordial follicle activation23 (Fig. 1A). Loss of Foxl2 results in inhibition of granulosa cell proliferation, oocyte growth, and failure of more advanced follicles to form by repression of essential steroidogenic genes (steroidogenic acute regulatory protein [Stard1], cytochrome P450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 [Cyp19a1], and cytochrome P450, family 11, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 [Cyp11a1]).81 Amh knockout mice are fertile until 4 months of age when the number of primordial follicles are found to be depleted and continue to decrease throughout the remainder of the mouse’s reproductive life.23 Mutations in FOXL28 cause blepharophimosis–ptosis–epicanthus inversus syndrome, type I (BPESI) and II. Type I can present with POI. Multiple mutations in FOXL2 have also been found in women with nonsyndromic POI,82–85 suggesting that mutations in FOXL2 may be a cause of idiopathic POI (Table 1). In humans, a SNP in AMH (rs10407022) and two SNPs in the corresponding receptor, AMH type 2 receptor (AMHR2), have been implicated in determining age at menopause in a European population of women80,86,87 (Table 2).

Hormonal regulation of folliculogenesis involves multiple genes that may affect ovarian reserve. Granulosa cells and theca cells cooperate to produce the steroids essential for proper oocyte production. Granulosa cells are the primary site of estradiol production, which is essential for proper antral follicle formation and maintenance, as well as ovulation (Fig. 1B). Estrogen receptors facilitate these actions; therefore, loss of either estrogen receptor 1 or 2 (Esr1 or Esr2, respectively) leads to loss of fertility.88 To produce estradiol, granulosa cells must utilize the products produced by theca cells. LH induces expression of key steroidogenic enzymes in theca cells through its receptor, LH/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHCGR), on theca cells. LH stimulates oocyte meiotic resumption, cumulus expansion, follicle rupture, and terminal differentiation of granulosa cells to corpora lutea. Mice deficient in Lh or Lhcgr are infertile and lack proper steroido-genesis with most follicles arrested at the preantral stage.48 Activation of LHCGR induces the expression of Stard1, Cyp11a1 (also known as side chain cleavage enzyme), hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 β- and steroid delta-isomerase 1 (Hsd3b1), and cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 (Cyp17a1).48 Theca cells produce androstenedione and testosterone, which can be utilized by the granulosa cells to produce estradiol.

FSH acts on granulosa cells through its receptor (FSHR) to upregulate Cyp19a1 (commonly known as aromatase) and hydroxysteroid (17-β) dehydrogenase 1 (Hsd17b1) in granulosa cells to stimulate estradiol production.48 Mice lacking Cyp19a1 had impaired ovulation and displayed uneven granulosa cell layers in the antral follicles, increased follicular atresia, and increased tumor protein 53 (Tp53) and Bax expression89 (Fig. 1B). FSH is critical for prevention of follicular atresia and enhancement of granulosa cell proliferation. FSH stimulates the upregulation of LHCGR in theca cells. Mice lacking Fsh or Fshr fail to form antral follicles48 (Fig. 1B). An additional growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), increases granulosa cell responsiveness to FSH. Mice lacking Igf1 also fail to form preantral follicles.48 INHA, whose expression is partially controlled by GDF9, functions to inhibit FSH secretion from the hypothalamus in a negative feedback loop48 (Fig. 1B).

FSHR mutations cause ovarian dysgenesis in humans. Missense SNPs in FSHR, c.566C > T (p.A189V) and c.1255G > A (p.A419T), were shown to be inherited in a classical Mendelian autosomal recessive manner predominantly in Finnish populations90–92 (Table 1). Additional mutations have also been identified in women of Indian descent, including a mutation at the 29 position in the 5′-untranslated region, present in patients with amenorrhea (7 of 48 primary or 6 of 48 secondary) and elevated FSH. In addition, a novel mutation in one POI patient was identified at c.1723C > T (p. A575V).93 Variants in FSHR were evaluated in menopausal women but were not found to associate with age at meno-pause.94 However, mutations in FSHR are overall scarce in women with POI outside of Finland. This is likely due to FSHR mutation arising in Finland and spreading within its population, but not outside, due to its insular reproductive history.

Given the findings in FSHR and due to their importance in ovarian physiology, genes encoding many of the other key hormonal regulators and steroidogenic enzymes have been investigated in women with POI (Table 1) or in the onset of menopause (Table 2) and have recently been reviewed.95 A SNP in the 3′ untranslated region of LHCGR is significantly associated with the age at menopause in a population of 24,341 Caucasian women96 (Table 2). Variants in FSH β (FSHB; rs11031010, rs621686, and rs7951733) were found to significantly associate with the age at menopause in this same population of Caucasian women.96 However, of these FSHB SNPs, only rs11301010 was also found to significantly associate with age at menopause in a population of 1,860 African American women97 (Table 1). All of the variants tested in FSHB lie in either the 5′ or 3′ untranslated region of the gene; thus, their effects on protein function remain to be determined.95 It is important to note that GWASs in African American populations require larger numbers to yield strong associations, due to lower linkage disequilibrium among Africans as compared with other populations.98,99

Variants outside of the coding sequences of CYP19A1 associate with POI and menopause. An intronic variant in CYP19A1 (rs11856927) was found to be significantly associated with age at menopause in the Caucasian population, but not the African American population96,97 (Table 2). Heterozygosity at one of three SNPs in CYP19A1 (rs6493489, rs6493488, and rs10046) was found to increase the odds ratio of presenting with POI to a value of least 2 in a Korean population of 98 POI patients100,101 (Table 1). Evaluation of Chinese women with POI did not reveal any significant variants within CYP19A1.59 The presence of the IGF1 intronic SNP, rs1019731, was not found to significantly contribute to Chinese women with POI102 or to the age at onset of meno-pause in African American women.97 However, this IGF1 variant was found to significantly contribute to age at onset of menopause in a population of 24,341 Caucasian women96 (Table 2). Mutations in the promoter region of INHA have been evaluated in Korean, European, Slovenian, and New Zealand POI patients103–106; however, only c. –16C > T in 4 of 138 affected Slovenian women was significantly associated with POI (p ¼ 0.029; Table 1).107

Three SNPs have been identified in ESR1 and have been studied in multiple populations. Intronic variant, rs1569788, was not found to significantly associate with onset of POI in Korean and Chinese populations.100–102ESR1 SNP, rs2234693, was found to confer some level of resistance to POI in Korean women108; this same SNP was significantly associated with onset of POI in populations of Chinese (population of 371 POI and 800 control women; p = 0.009057), Brazilian (population of 48 POI, 348 infertile, and 200 fertile controls), and European (Swiss; population of 70 POF and 73 menopausal controls, p = 0.034), with an odds ratios102,109,110 exceeding 2.2 (Table 1). Indeed, rs2234693 is associated with age at onset of menopause in Chinese women102 (Table 2). The third ESR1 SNP, rs9340799, was found to be related to reduced risk of POI in Korean women but not in Chinese or Brazilian populations.102,108,109 Two variants in ESR2 were investigated in the Brazilian population, but neither was found to associate with POI.109 Two variants in ESR2were investigated in the Brazilian population, but neither was found to associate with POI.109

Syndromic Pathologies that Diminish Ovarian Reserves

Women who have phenotypic abnormalities in addition to ovarian insufficiency are likely to have syndromic, as opposed to nonsyndromic (pathology confined to ovarian insufficiency) type of POI. These syndromes can be due to chromosomal abnormalities such as Turner syndrome (monosomy X) or due to single gene mutations as is the case with galactosemia (GALT), pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a (guanine nucleotide binding protein, α stimulating; GNAS1), progressive external ophthalmoplegia (polymerase [DNA directed], gamma; POLG), autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (autoimmune regulator; AIRE), ovarian leukodystrophy (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2B, subunit 2 β; EIF2B2), Ataxia Telangiectasia (ATM), Demirhan syndrome (bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type 1B; BMPR1B), and BPESI (FOXL2)8 among others. Women with nonsyndromic and idiopathic POI were evaluated for the presence of EIF2B2 and GALT mutations; however, no significant associations were found.111,112 Mice lacking Atm, Aire, or Bmpr1b also have ovarian dysfunction,113–115 although mutations in these genes have not been evaluated in patients with nonsyndromic and idiopathic POI. A SNP in POLG (rs2307449) associates with age at menopause.116,117

Fragile X mental retardation gene (FMR1) is currently the only gene recommended for clinical testing in women with POI. The 5′-untranslated region of FMR1 gene contains a CGG repeat that is usually 29 to 30 repeats in length. When the number of CGG repeats is between 55 and 199, this mutation is referred to as a premutation because it does not associate with the neurological effects of fragile X syndrome.8 Women with sporadic POI have a 0.8 to 7.5% chance of having a premutation. Women known to carry the premutation have a 13% chance of presenting with POI. It is unclear how the premutation leads to POI, as the full mutation (> 199 repeats) is not associated with POI, despite the loss of FMR1 protein. The premutation repeats may interfere with posttranscriptional metabolism of the oocytes. A mouse model of the Fmr1 premutation resulted in an accumulation of Fmr1 mRNA carrying the permutations repeats. Elevated levels of premutation mRNA contributes to a decreased number of advanced follicles beginning with Pedersen and Peters' type 6 follicles (follicles with large oocytes, multiple cell layers, and incomplete antrum formation)118 but did not have a reduction in the number of primordial follicles119 (Fig. 1B). The reduction in numbers of advanced follicles may be due to increased apoptosis or downregulation of genes essential for late folliculogenesis, including Lhcgr.119 Premutation mice were sub-fertile with fewer pups per litter. Although it has long been known that Fmr1 premutation contributed to the onset of POI, this is the first demonstration that despite an increase in Fmr1 mRNA, there is not an increase in protein, and that the elevated level of Fmr1 premutation mRNA alone is sufficient to cause ovarian dysfunction. The mechanisms behind the ovarian pathology are not well understood. Intriguingly, this mouse model also revealed a reduction in phosphorylation of AKT1 and MTOR proteins, promoters of primordial follicle activation.119 Although not directly examined, loss of AKT1 and MTOR phosphorylation may lead to decreased shuttling of FOXO3 out of the nucleus; thus, the ovarian reserve may be preserved and may explain the comparable numbers of primordial follicles found in wild-type and premutation models.119 Therefore, if this paradigm holds in humans, it would be expected that the ovarian reserve in women with FMR1 premutation should not be dramatically reduced. Although the levels of AMH decline and FSH levels increase in women with greater numbers of CGG repeats,120–122 ovarian biopsies to quantitate primordial follicle numbers is lacking. Women who carry FMR1 premutations are not only at risk for POI but also at risk of having male children with fragile X syndrome. Such individuals require genetic counseling as well as assessment of other family members for premutation carrier status.

Genomic Imbalances and Ovarian Reserves

Identification of genomic imbalances can provide insights into the involvement of genes or chromosomal region in diseases, like POI. Investigation of karyotypes for translocations, duplications, and deletions has led to the identification of key genes involved in ovarian function and the onset of POI. Chromosomal abnormalities occur in 8.8 to 21.3% of women with POI depending on the population and size of study.123–129 Evaluation of chromosomal abnormalities by karyotype (recently reviewed12,130) has linked large regions of the X chromosome to the presence of POI, including monosomy X (Turner syndrome), trisomy X, and mosaicism.125,131 Several key regions on the X chromosome have been identified as essential for ovarian function by karyotype analysis: Xq27–28,126,132–135 Xq13.3– 22,123,124,126,136–139 Xp13.1-p11,137,140 and Xq22–25.135,141 Within these regions, genes are present that are known to contribute to ovarian function including FMR1 (q27.3), inactive X-specific transcripts (XIST; q13.2), diaphanous homolog 2 (DIAPH2; q21.33), BMP15 (p11.2), and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP; q25). Translocations of the X chromosome with other autosomes have also been found in patients with POI, including chromosomes 1,123,142 2,143,144 9,123,135,144 11,145 13,143 14,146 15,147,148 18,149 19,143,144 22,150 and Y.143,144,151 Translocations between autosomes have also been identified in women with POI.123,144 Despite identification of relevant genes on the X chromosome which are disrupted by breakpoints from translocations, position effects may also contribute to the loss of ovarian function found in POI.

While karyotypes can provide information on large chromosomal abnormalities, array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) can identify smaller duplications or deletions that are missed by karyotype. Karyotype can identify genomic imbalances greater than 5 million base–pairs, while aCGH resolution can be as high as few hundred base–pairs. Several copy number variants were identified through the use of tiling arrays on the X chromosome in 42 idiopathic POI patients.152 Gains were identified in p22.31, p11.4, q12, q23.3–21.3, and q26.3.152 Losses were identified in q22.11-p21.3, p11.4, p11.23–11.22, q22.1–22.2, q22.2, q23–24, and q25.152 SNP arrays were used to identify microdeletions on autosomes and found microdeletions on 8q24.13, 10p15-p14, 10q23.31, 10q26.3, 15q25.2, and 18q21.32.153 Specifically of interest is the identification of microdeletions within synaptonemal complex central element protein 1 (SYCE1) and cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1 (CPEB1), which have been shown to cause POI in mouse models.153 Array CGH was used to identify 1p21.1, 5p14.3, 5q13.2, 6p25.3, 14q32.33, 16p11.2, 17q12, and Xq28 as statistically significant copy number variants in women with POI.154 These regions included disruption in genes that may be involved in reproductive function, including dynein, axonemal, heavy chain 5 (DNAH5), NLR family, apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP), dual specificity phosphatase 22 (DUSP22), AKT1, and nuclear protein transcriptional regulator 1 (NUPR1).154 Array CGH technology is evolving into a useful diagnostic tool to determine clinically relevant genomic imbalances that might be missed by karyotyping.

Genome-Wide Association Studies

Natural menopause: Recent large-scale GWASs 63,96,97,117,155,156 (Table 2) have identified loci that could be used to predict the age at onset of menopause and thus the natural depletion of ovarian reserve. These loci have highlighted genes involved in DNA repair (POLG; exonuclease 1 [EXO1]; helicase, POLQ-like [HELQ]; ubiquitin interaction motif containing 1 [UIMC1]; Fanconi anemia [FANCI]; tousled-like kinase 1 [TLK1]; and primase, DNA, polypeptide 1 [PRIM1])117 and steroid-hormone metabolism and biosynthesis pathways (CYP19A1; FSHB; LHCGR; IGF1; progesterone receptor [PGR]; steroid-5-α-reductase, α polypeptide 1 [SRD5A1]; insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor [IGF2R]; mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7 [SMAD7]; transforming growth factor β receptor 1 [TGFBR1]; proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 [PCSK1]; peroxi-some proliferation-activated receptor gamma [PPARG]; tumor necrosis factor [TNF]; eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2B, subunit 4 delta [EIF2B4]; nibrin [NBN]; and ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 [ANKK1]).96 These key pathways are natural avenues of investigation when discussing loss of function of the organ and aging.

In a large meta-analysis of 22 GWAS, four genes harboring nonsynonymous SNPs were identified as being significantly associated with age at menopause, including minichromo-some maintenance complex component 8 (MCM8), PRIM1, proline-rich coiled-coil 2A (PRRC2A/BAT2), and NLR family, pyrin domain containing 11 (NLRP11).117,157 One synonymous and 12 intronic SNPs were also identified. It is important to recognize that SNP associations do not guarantee that the SNP itself is causative of the phenotype, but a marker for nearby genetic pathology that was not genotyped. Moreover, the current SNPs account for only 2.5 to 4.1% percent of age at menopause association.117 Nonetheless, some of the non-synonymous SNPs lie in genes that have important functions in folliculogenesis as revealed by animal models. For example, the SNP in MCM8 (rs16991615) could lead to a potentially damaging mutation in the resulting protein. Significance of MCM8 mutations with respect to age at menopause was confirmed in Hispanic, American Indian, and European American women,117,155,158–160 but was not significant in an African American population.97,155 MCM8 is expressed within the oocyte in primordial, primary, and secondary follicles of human ovaries.155 Mcm8 knockout mice are sterile with female mice having dysplastic primary follicles and a block in follicle development due to inhibition of homologous recombination-mediated double-strand break repair161 (Fig. 1A). PRIM1 is a DNA primase involved in noncontinuous DNA replication, and studies of Prim1 in Danio rerio revealed that a missense mutation of phenylalanine 110 in a highly conserved region essential for enzyme activity in the Prim1 gene lead to apoptosis through activation of the Atm/checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2)/Tp53 DNA damage pathway.162 However, PRIM1 has not been studied exclusively in the reproductive tract of mice or humans. PRRC2A is a member of the MHC class III genes whose functions and structures are not well defined. Yeast-two hybrid analyses predict PPRC2A to function in mRNA splicing due to binding with known mRNA splicing machinery, including HNRNPA1 and C1QBP.163PPRC2A has been associated with inflammatory pathways and an association with increased susceptibility for rheumatoid arthritis,164 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus,165 obesity,166 and cancer.167,168 However, to our knowledge, PRRC2A has not been evaluated in animal models or in reproductive systems. As discussed above (see “Nobox promotes primor-dial follicle activation”), NOBOX can enhance the expression of NLRP family members which in turn may prevent oocyte depletion through ablation of inflammatory pathways. Although NLRP11 does not have an identified mouse homolog and it is unknown if NOBOX directly regulates NLRP11, the role of NLRP11 in inflammatory pathways is supported by its recent association with Crohn disease169 and systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis.170

Additional GWASs and targeted genotyping for identified SNPs allowed identification of SNPs that are significantly associated with age of menopause in multiple ethnic populations. Several genes appear to be significant in more than one population, brain-specific serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (BRSK1/TMEM150B), PPARG, cytochrome P450, family 1, sub-family B, polypeptide 1 (CYP1B1), apolipoprotein E (APOE), synaptonemal complex protein 2-like (SYCP2L), hexokinase 3 (HK3), and UIMC1. Twelve SNPs in the BRSK1/TMEM150B gene locus were found to be associated with age at menopause in Caucasian (GWAS; 17,500 women),160 Hispanic (targeted genotyping; 3,642 women),159 Chinese (targeted genotyping; combined ~4,000 women),102,116 and African American (tar- geted genotyping; 1,860 women)97 populations117,160 (Table 2). Brsk1 can control centrosome numbers during cell division,171 and may function as a cell cycle checkpoint in response to DNA damage.172 Brsk1 / mice are normal and fertile; therefore, the Brsk1 mouse model may not reflect what happens in humans or nonsynonymous mutations may be more deleterious due to dominant negative effects than loss of function mutations.173 SNPs within the PPARG gene were significantly associated with age at menopause in Caucasian (GWAS) and Korean populations but not African American women (targeted genotyping and GWAS).96,97,174Pparg / mice die in utero due to placental defects.175 Elimination of Pparg specifically in granulosa cells and oocytes caused infertility or subfertility in one-third of females due to implantation deficiencies as follicle numbers and ovulated oocytes did not differ from controls176 (Fig. 1B). Targeted sequencing of cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily B, and polypeptide 1 (CYP1B1) revealed four variants that contribute to age at menopause in Chinese women (1,958) or European women (1,360).177,178 Cyp1b1 is essential for proper steroid formation in adrenals and gonads. APOE, SCYP2L, HK3, and UIMC1 have all been implicated in multiple ethnic populations as being associated with age at menopause, but their functions are not well characterized (Table 2). Additional SNPs were identified as being correlated with menopause; however, the majority of these were found only in menopausal women of a distinct heritage. In African American populations, SNPs in low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), potassium voltage-gated channel, KQT-like subfamily, member 1 (KCNQ1), and collagen, type IV, α 3 (Goodpasture antigen) binding protein (COL4A3BP) were found to be most significantly associated with age at natural menopause and were not previously identified in other studies.161

Early menopause: A recent GWAS evaluated genetic variants associated with early menopause (< 45 years of age) in women of European ancestry63 (Table 2). Single variants in corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1), solute carrier family 25 (aspartate/glutamate carrier), member 13 (SLC25A13), mini-chromosome maintenance complex component 6 (MCM6), and MB21D1/C6ORF150 (discussed earlier) significantly associated with age at early menopause. Mice lacking Crhr1 and Slc25a13 do not have known fertility defects.179,180Mcm6 has not been specifically evaluated in mammalian systems, but in Drosophila, several Mcm6 mutations result in females with infertility or females who lay eggs with thin shells.181Mcm6 is essential for replication by identifying origins of replication. Cyclin E/cyclin-dependent kinase 1 phosphorylation of Mcm6 results in the targeting of Double parked (DUP), an inhibitor of cell cycle progression, for degradation.181,182 Additionally, when the set of 17 menopause-associated loci from GWAS117 were evaluated for risk of early menopause, together these loci provided an increased odds ratio of 2.47.63 This combined risk was greater than the largest nongenetic contributor to POI, smoking. However, these 17 loci only attributed to < 5% of the differences found in menopausal age.63 Therefore, more large-scale genome-wide linkage analyses must be conducted to characterize this polygenic trait and to determine a person's risk for early menopause.

Conclusion

For the individual who is affected with loss of ovarian reserves, identification of genetic causes underlying POI is an essential part of the clinical evaluation, genetic counseling, and risk assessment. Accurate genetic diagnosis presents an opportunity to guide treatment options, and provides important information regarding the health and reproductive potential of an affected individual. Moreover, genetic counseling of the couple is essential to provide risk of transmitting genetic abnormalities to the offspring, especially for individuals who cryopreserved their gametes and underwent POI. Recording of a careful family history is necessary to determine if there is a clear familial pattern of infertility, miscarriages, skewed gender ratios (e.g., complete androgen insensitivity syndrome), accelerated aging, and syndromic causes associated with infertility (Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, and Ataxia telangiectasia). However, a negative family history does not rule out genetic contribution, as de novo genetic events likely account for a substantial number of sporadic cases; examples include most chromosomal abnormalities, such as Turner syndrome. Karyotype analysis of peripheral blood samples should be performed as an initial component of evaluation for female infertility to identify sex chromo-some aneuploidy and gross structural chromosome rearrangements.

In case of a normal karyotype, expanded genetic testing should include microarray analysis to detect submicroscopic chromosome abnormalities, and depending on gathered clinical information, a possible individual gene mutation analysis, such as FMR1. Gonadal failure and recurrent pregnancy losses of male fetuses have been associated with submicroscopic X chromosome deletions and duplications.153,154,183FMR1 testing for the CGG repeat in the 5′ untranslated region of the gene is essential to rule out premutation carrier status, and is now recommended for all women with cessation of menses and elevated gonadotropin levels before the age of 40. Women found to have FMR1 premutation are themselves at risk for POI and are also at risk for fragile X-associated tremor and ataxia syndrome, while their offspring is at risk for mental retardation syndrome. It is important to note that negative genetic testing does not exclude genetic pathology, as there are other, presently unknown, genes that are implicated in normal gametogenesis. Whole exome/genome sequencing is now a logical extension of the molecular karyotype to define genetic pathology at the nucleotide level. In families with a clear genetic etiology, a combination of SNP arrays to determine regions of homozygosity and whole exome/ genome sequencing will have a high chance of identifying causative mutations, which can be used to assess risk in younger individuals within the family. Consanguineous families with multiple individuals affected by POI whose phenotypes segregate in autosomal recessive fashion are ideal candidates for this type of analysis and can provide younger individuals at risk the opportunity to utilize cryopreservation technologies. The task is more difficult in cases of sporadic POI. Family pedigree and blood from affected and unaffected relatives will be important in sporadic cases to sift through the variants that may or may not responsible for premature depletion of ovarian reserves. Individuals with sporadic POI, less than 25 years of age, are more likely to have a penetrant genetic form of POI, than individuals who are older. Genetic counseling should be ideally provided before the genetic test is offered so that the couple understands the pros and cons of genetic testing. Post-test genetic counseling is necessary for the couple to understand the significance of each possible outcome: normal results, pathologic test findings, and findings of unknown clinical significance. It is essential that gynecologists are engaged with clinical genetic experts, including genomic laboratories, to provide the most optimal and appropriate testing to their patients.

There are currently no genomic markers in regular clinical use to predict ovarian reserves in the general population. Current genetic evaluation is limited to women who present with reproductive pathologies such as POI, gonadal dysgenesis, primary amenorrhea, and, as described above, karyotype and FMR1 premutation testing. Studies in mice and humans have identified more than 400 genes that disrupt ovarian development and/or function, and there are many more to be yet discovered. This is not surprising, as ovarian development involves interaction of many genes. Such genetic heterogeneity makes finding a dominant genetic determinant of ovarian reserve less likely, and unsurprisingly, many of the single gene candidate studies have shown poor associations with premature depletion of ovarian reserves. GWASs have identified genetic markers that account only for roughly 5% percent of the difference in age at menopause. Many of the past studies linking genes to ovarian reserves have focused on protein coding genes. Less than 5% of the total human genome sequence codes for proteins. The role of epigenetics, noncoding RNAs, and gene regulatory regions has not been well explored. Moreover, recent results from the ENCODE consortium suggests that large portions of the noncoding genome play functional and regulatory roles.184

Defining a unique set of genomic biomarkers to determine ovarian reserve will require individualized genomic approaches in the future. Initial genetic analyses will focus on the genes implicated in ovarian development and function, to determine if mutations can be identified. Many of the identified mutations will be private, and functional analysis, or an appropriate database collection of individuals with same mutation will be required to determine causality. Databases that harbor genome sequences from ethnically matched, phenotypically normal fertile women will become essential for research endeavors as well as clinical interpretation of various variants. Genomic data will need to be interpreted in the background of family and medical history. To predict reproductive lifespan, integration of genomic data with proteomics, including AMH and other serum markers, as well as imaging and epigenetic data, is required. Additional research and establishment of the computational resources required to conduct such integration are beyond reach of individual laboratories. Collaborative and large-scale efforts are necessary to bring genomic promise of personalized ovarian health to the clinical realm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Rajkovic laboratory for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Magee-Womens Research Institute Fellowship (M.A.W.) and the NICHD, 5HD070647–02 (A.R.).

References

- 1.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. NCHS Data Brief. Vol. 21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. Delayed childbearing: more women are having their first child later in life. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milan A. Report on the Demographic Situation in Canada. Component of Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 91-209-X. Government of Canada; 2013. Fertility: overview, 2009 to 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broekmans FJ, Soules MR, Fauser BC. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(5):465–493. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen MP, Johnstone E, McCulloch CE, et al. A characterization of the relationship of ovarian reserve markers with age. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagarlamudi K, Rajkovic A. Oogenesis: transcriptional regulators and mouse models. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;356(1–2):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarraj MA, Drummond AE. Mammalian foetal ovarian development: consequences for health and disease. Reproduction. 2012;143(2):151–163. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palma GA, Argañaraz ME, Barrera AD, Rodler D, Mutto AA, Sinowatz F. Biology and biotechnology of follicle development. Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:938138. doi: 10.1100/2012/938138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Persani L, Rossetti R, Cacciatore C. Genes involved in human premature ovarian failure. J Mol Endocrinol. 2010;45(5):257–279. doi: 10.1677/JME-10-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGee EA, Hsueh AJ. Initial and cyclic recruitment of ovarian follicles. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(2):200–214. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru JK, Tilly JL. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428(6979):145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature02316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Kawamura K, Cheng Y, et al. Activation of dormant ovarian follicles to generate mature eggs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(22):10280–10284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001198107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin M, Yu Y, Huang H. An update on primary ovarian insufficiency. Sci China Life Sci. 2012;55(8):677–686. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris DH, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ. Familial concordance for age at natural menopause: results from the Breakthrough Generations Study. Menopause. 2011;18(9):956–961. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31820ed6d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murabito JM, Yang Q, Fox C, Wilson PW, Cupples LA. Heritability of age at natural menopause in the Framingham Heart Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3427–3430. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Asselt KM, Kok HS, Pearson PL, et al. Heritability of menopausal age in mothers and daughters. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(5):1348–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snieder H, MacGregor AJ, Spector TD. Genes control the cessation of a woman's reproductive life: a twin study of hysterectomy and age at menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(6):1875–1880. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson JL, Rajkovic A. Ovarian differentiation and gonadal failure. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89(4):186–200. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991229)89:4<186::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soyal SM, Amleh A, Dean J. FIGalpha, a germ cell-specific transcription factor required for ovarian follicle formation. Development. 2000;127(21):4645–4654. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bayne RA, Martins da Silva SJ, Anderson RA. Increased expression of the FIGLA transcription factor is associated with primordial follicle formation in the human fetal ovary. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10(6):373–381. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao H, Chen ZJ, Qin Y, et al. Transcription factor FIGLA is mutated in patients with premature ovarian failure. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(6):1342–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huntriss J, Gosden R, Hinkins M, et al. Isolation, characterization and expression of the human Factor In the Germline alpha (FIGLA) gene in ovarian follicles and oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8(12):1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.12.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pangas SA, Choi Y, Ballow DJ, et al. Oogenesis requires germ cell-specific transcriptional regulators Sohlh1 and Lhx8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(21):8090–8095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601083103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pangas SA. Regulation of the ovarian reserve by members of the transforming growth factor beta family. Mol Reprod Dev. 2012;79(10):666–679. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi Y, Yuan D, Rajkovic A. Germ cell-specific transcriptional regulator sohlh2 is essential for early mouse folliculogenesis and oocyte-specific gene expression. Biol Reprod. 2008;79(6):1176–1182. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.071217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi Y, Ballow DJ, Xin Y, Rajkovic A. Lim homeobox gene, lhx8, is essential for mouse oocyte differentiation and survival. Biol Reprod. 2008;79(3):442–449. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin Y, Zhao H, Kovanci E, Simpson JL, Chen ZJ, Rajkovic A. Analysis of LHX8 mutation in premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(4):1012–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzumori N, Yan C, Matzuk MM, Rajkovic A. Nobox is a homeobox-encoding gene preferentially expressed in primordial and growing oocytes. Mech Dev. 2002;111(1–2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajkovic A, Pangas SA, Ballow D, Suzumori N, Matzuk MM. NOBOX deficiency disrupts early folliculogenesis and oocyte-specific gene expression. Science. 2004;305(5687):1157–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.1099755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lechowska A, Bilinski S, Choi Y, Shin Y, Kloc M, Rajkovic A. Premature ovarian failure in nobox-deficient mice is caused by defects in somatic cell invasion and germ cell cyst breakdown. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28(7):583–589. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi Y, Qin Y, Berger MF, Ballow DJ, Bulyk ML, Rajkovic A. Microarray analyses of newborn mouse ovaries lacking Nobox. Biol Reprod. 2007;77(2):312–319. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.060459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi Y, Rajkovic A. Genetics of early mammalian folliculogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63(5):579–590. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5394-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huntriss J, Hinkins M, Picton HM. cDNA cloning and expression of the human NOBOX gene in oocytes and ovarian follicles. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12(5):283–289. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin Y, Choi Y, Zhao H, Simpson JL, Chen ZJ, Rajkovic A. NOBOX homeobox mutation causes premature ovarian failure. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):576–581. doi: 10.1086/519496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouilly J, Bachelot A, Broutin I, Touraine P, Binart N. Novel NOBOX loss-of-function mutations account for 6.2% of cases in a large primary ovarian insufficiency cohort. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(10):1108–1113. doi: 10.1002/humu.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sehested LT, Møller RS, Bache I, et al. Deletion of 7q34-q36.2 in two siblings with mental retardation, language delay, primary amenorrhea, and dysmorphic features. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(12):3115–3119. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi E, Verri AP, Patricelli MG, et al. A 12Mb deletion at 7q33-q35 associated with autism spectrum disorders and primary amenorrhea. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51(6):631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Wang B, Song J, et al. New candidate gene POU5F1 associated with premature ovarian failure in Chinese patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22(3):312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsson EE, Kezele P, Skinner MK. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) promotes the primordial to primary follicle transition in rat ovaries. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;188(1–2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrios F, Filipponi D, Campolo F, et al. SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 control Kit expression during postnatal male germ cell development. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 6):1455–1464. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang EJ, Manova K, Packer AI, Sanchez S, Bachvarova RF, Besmer P. The murine steel panda mutation affects kit ligand expression and growth of early ovarian follicles. Dev Biol. 1993;157(1):100–109. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuroda H, Terada N, Nakayama H, Matsumoto K, Kitamura Y. Infertility due to growth arrest of ovarian follicles in Sl/Slt mice. Dev Biol. 1988;126(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCoshen JA, McCallion DJ. A study of the primordial germ cells during their migratory phase in Steel mutant mice. Experientia. 1975;31(5):589–590. doi: 10.1007/BF01932475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith ER, Yeasky T, Wei JQ, et al. White spotting variant mouse as an experimental model for ovarian aging and menopausal biology. Menopause. 2012;19(5):588–596. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318239cc53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui ES, Udofa EA, Soto J, et al. Investigation of the human stem cell factor KIT ligand gene, KITLG, in women with 46,XX spontaneous premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(5):1502–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.John GB, Gallardo TD, Shirley LJ, Castrillon DH. Foxo3 is a PI3K-dependent molecular switch controlling the initiation of oocyte growth. Dev Biol. 2008;321(1):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reddy P, Liu L, Adhikari D, et al. Oocyte-specific deletion of Pten causes premature activation of the primordial follicle pool. Science. 2008;319(5863):611–613. doi: 10.1126/science.1152257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.John GB, Shidler MJ, Besmer P, Castrillon DH. Kit signaling via PI3K promotes ovarian follicle maturation but is dispensable for primordial follicle activation. Dev Biol. 2009;331(2):292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Matzuk MM. The mammalian ovary from genesis to revelation. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(6):624–712. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan SD, Castrillon DH. Insights into primary ovarian insufficiency through genetically engineered mouse models. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(4):283–298. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reddy P, Adhikari D, Zheng W, et al. PDK1 signaling in oocytes controls reproductive aging and lifespan by manipulating the survival of primordial follicles. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(15):2813–2824. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adhikari D, Risal S, Liu K, Shen Y. Pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 prevents over-activation of the primordial follicle pool in response to elevated PI3K signaling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adhikari D, Gorre N, Risal S, et al. The safe use of a PTEN inhibitor for the activation of dormant mouse primordial follicles and generation of fertilizable eggs. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao Z, Qin Y, Ma J, et al. PTEN gene analysis in premature ovarian failure patients. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(6):678–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimizu Y, Kimura F, Takebayashi K, Fujiwara M, Takakura K, Takahashi K. Mutational analysis of the PTEN gene in women with premature ovarian failure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(7):824–825. doi: 10.1080/00016340902971458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.John GB, Shirley LJ, Gallardo TD, Castrillon DH. Specificity of the requirement for Foxo3 in primordial follicle activation. Reproduction. 2007;133(5):855–863. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu L, Rajareddy S, Reddy P, et al. Infertility caused by retardation of follicular development in mice with oocyte-specific expression of Foxo3a. Development. 2007;134(1):199–209. doi: 10.1242/dev.02667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rajareddy S, Reddy P, Du C, et al. p27kip1 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B) controls ovarian development by suppressing follicle endowment and activation and promoting follicle atresia in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(9):2189–2202. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halperin J, Devi SY, Elizur S, et al. Prolactin signaling through the short form of its receptor represses forkhead transcription factor FOXO3 and its target gene galt causing a severe ovarian defect. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(2):513–522. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang B, Ni F, Li L, et al. Analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B mutation in Han Chinese women with premature ovarian failure. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21(2):212–214. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ojeda D, Lakhal B, Fonseca DJ, et al. Sequence analysis of the CDKN1B gene in patients with premature ovarian failure reveals a novel mutation potentially related to the phenotype. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2658–2660. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gallardo TD, John GB, Bradshaw K, et al. Sequence variation at the human FOXO3 locus: a study of premature ovarian failure and primary amenorrhea. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(1):216–221. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solc P, Schultz RM, Motlik J. Prophase I arrest and progression to metaphase I in mouse oocytes: comparison of resumption of meiosis and recovery from G2-arrest in somatic cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16(9):654–664. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perry JR, Corre T, Esko T, et al. ReproGen Consortium. A genome-wide association study of early menopause and the combined impact of identified variants. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(7):1465–1472. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenfeld CR, Pepling ME, Babus JK, Furth PA, Flaws JA. BAX regulates follicular endowment in mice. Reproduction. 2007;133(5):865–876. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perez GI, Jurisicova A, Wise L, et al. Absence of the proapoptotic Bax protein extends fertility and alleviates age-related health complications in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(12):5229–5234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608557104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dong J, Albertini DF, Nishimori K, Kumar TR, Lu N, Matzuk MM. Growth differentiation factor-9 is required during early ovarian folliculogenesis. Nature. 1996;383(6600):531–535. doi: 10.1038/383531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galloway SM, McNatty KP, Cambridge LM, et al. Mutations in an oocyte-derived growth factor gene (BMP15) cause increased ovulation rate and infertility in a dosage-sensitive manner. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):279–283. doi: 10.1038/77033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan C, Wang P, DeMayo J, et al. Synergistic roles of bone morpho-genetic protein 15 and growth differentiation factor 9 in ovarian function. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15(6):854–866. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.6.0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dixit H, Rao LK, Padmalatha V, et al. Mutational screening of the coding region of growth differentiation factor 9 gene in Indian women with ovarian failure. Menopause. 2005;12(6):749–754. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000184424.96437.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao H, Qin Y, Kovanci E, Simpson JL, Chen ZJ, Rajkovic A. Analyses of GDF9 mutation in 100 Chinese women with premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 2007;88(5):1474–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]