Abstract

Reversal of DNA hypermethylation and associated gene silencing is an emerging cancer therapy approach. Here we addressed the impact of epigenetic alterations and cellular context on functional and transcriptional reprogramming of HCC cells. Our strategy employed a 3-day treatment of established and primary human HCC-derived cell lines grown as monolayer at various cell densities with the DNMT1 inhibitor Zebularine (ZEB) followed by a 3D culture to identify cells endowed with self-renewal potential. Differences in self-renewal, gene expression, tumorigenicity and metastatic potential of spheres at generations G1-G5 were examined. Transient ZEB exposure produced differential cell density-dependent responses. In cells grown at low density, ZEB caused a remarkable increase in self-renewal and tumorigenicity associated with long-lasting gene expression changes characterized by a stable overexpression of cancer stem cell-related and key epithelial-mesenchymal transition genes. These effects persisted after restoration of DNMT1 expression. In contrast, at high cell density, ZEB caused a gradual decrease in self-renewal and tumorigenicty, and up-regulation of apoptosis- and differentiation-related genes. A permanent reduction of DNMT1 protein using shRNA-mediated DNMT1 silencing rendered HCC cells insensitive both to cell density and ZEB effects. Similarly, WRL68 and HepG2 hepatoblastoma cells expressing low DNMT1 basal levels also possessed a high self renewal irrespective of cell density or ZEB exposure. Spheres formed by low density cells treated with ZEB or shDNMT1A displayed a high molecular similarity which was sustained through consecutive generations, confirming the essential role of DNMT1 depletion in the enhancement of cancer stem cell properties.

Conclusion

These results identify DNA methylation as a key epigenetic regulatory mechanism determining the pool of cancer stem cells in liver cancer and possibly other solid tumors.

Keywords: Cancer Stem Cells, DNMT1, Microenvironment, Reprogramming, HCC

Cellular and molecular heterogeneity is a hallmark of most solid tumors including liver cancer 1. Primary tumors harbor genetically and phenotypically distinct self-renewing cell subpopulations that promote a range of cancer growth patterns.1 The acquisition of stem/progenitor cells characteristics described both in murine models and most advanced human tumors supports the concept of cellular hierarchies in cancer with cancer stem cell (CSC; also referred to as tumor initiating cells) at the apex of tumor initiation.2

Cancer heterogeneity is dynamically regulated by genetic, epigenetic and cellular microenvironmental factors.3 Current evidence suggests that epigenetic reprogramming has critical roles in stem/cancer stem cell biology by maintaining pluripotency of stem cells and promoting differentiation to a more mature cell progeny.4,5 A key epigenetic reprogramming mechanism is DNA methylation. Methylation occurs predominantly at cytosine-C5 in the context of CpG dinucleotides, and is established and maintained by three DNA methyltransferases, DNMT3a, DNMT3b and DNMT1.6 DNMT3a and DNMT3b have mostly de novo DNA methylation activity, whereas DNMT1 plays a central role in preserving the patterns of DNA methylation through cell division.7

The inhibition of DNMT1 by 5-aza-cytidine (AZA) was able to greatly improve the overall efficiency of reprogramming process to the induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) state.8 AZA-mediated epigenetic modification of neurospheres derived from the mouse embryonic forebrain was shown to induce expression of several stem cells and pluripotency-associated genes likely via removal of epigenetic silencing.9 This notion is supported by the observation that inhibition of DNA methylation generates a transcriptional active chromatin structure thought to affect the global gene expression and influence cell fate decision. We have previously demonstrated that epigenetic modulation of liver cancer cells by Zebularine (ZEB), a potent DNMT1 inhibitor, facilitated functional enrichment of CSCs possessing self-renewal and tumor-initiating capacity supporting the hypothesis that DNA methylation plays a critical role in CSC biology.10,11

Recently, a key role in determining stem cell fate has been assigned to the biomechanics of cancer cell niche.12 Accumulating evidence suggests that CSC properties are regulated by context-dependent responses to the niche microenvironment defined by the composition of ECM, cell-to-cell contacts and growth factors and cytokines.12-14 Dramatic changes in matrix stiffness were directly implicated in promoting tumor growth, invasion and proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).14 Furthermore, restricting the spreading of stem cells on ECM could prevent activation of integrin-initiated signaling network causing a permanent exit from the cell cycle followed by initiation of a differentiation program.15 Manipulating the ECM stiffness in culture was also found to change chromatin remodeling and corresponding gene expression promoting differentiation of human epidermal cells16 and mammary epithelial cells.17

Few studies have addressed the impact of epigenetic alterations and local microenvironment on transcriptional reprogramming and functional properties of hepatic CSCs. We and others have recently reported that DNMT1 inhibition may facilitate functional enrichment of hepatic CSCs.10,11 However, the balance between CSC and non-CSC cells, particularly in the context of treatment with demethylating agents has not received much attention. Here we explore the response of CSC and non-CSC cells to a short-term treatment with the demethylating agent ZEB. The functional and molecular consequences of DNMT1 inhibition were analyzed in a 3D culture system to identify cells endowed with a long-term self-renewal capability,18,19 by transcriptome analysis and transplantation experiments in vivo. Our results demonstrate that epigenetic reprogramming induced by a transient DNMT1inhibition generates long-lasting cell context-dependent memory effects influencing both the malignant properties and the pool of hepatic CSCs.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and In Vitro Experiments

Zebularine was obtained from the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, NCI. shRNA lentiviral vector (Sigma,NM_001379.1-3261s1c1) was used for stable DNMT1 silencing. Tumor sphere culture was performed as described20 (Supporting Material and Methods).

Tumor Xenografts

All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health animal care committee. One hundred sphere-derived cells were resuspended in 200 μl DMEM and Matrigel (BD Bioscience) (1:1) and injected into flanks of NOD/SCID mice (Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research). (Supporting Material and Methods).

Microarray Analysis

Microarray was performed as described22 using Human HT12 beadchips (Illumina) (Supporting Material and Methods).

Immunofluorescence, western blotting, quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), histological analysis of tumors, and lentiviral production, were performed using standard assays described in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

Results

Transient DNMT1-Inhibition Has Cell Context-Dependent Effect on CSC Properties

To address the impact of cell density on epigenetic alterations in liver cancer, we first utilized Huh7 ZEB-sensitive cell line24 and used spherogenicity in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo as criteria of stemness properties (Supporting Fig. 1A). The cells were plated in 2D culture at various densities and exposed to a transient non-toxic dose of ZEB (100 μM) selected based on our previous studies.10,24 After a 3-day treatment, cells were dissociated and plated in the absence of ZEB at a clonal density in a 3D non-adherent condition. The results showed that the outcome of a short-term ZEB-treatment was cell-context dependent. In Huh7 cells grown under low density (LD, 2500 cell/cm2), ZEB enhanced and under high density (HD, 25000 cell/cm2) reduced the spherogenicity (Supporting Fig. 1B). Evaluating the sphere frequency after FACS-sorting of single cells into 96-plates confirmed this result (Supporting Fig. 1C).

Furthermore, when as few as 100 Huh7 cells grown under various experimental conditions were injected subcutaneously into immunocompromised mice, LD-ZEB cells were more effective in generating tumors as compared to LD not treated (LD-NT) and HD-ZEB cells which failed to produce tumors within the first five weeks of observation (Supporting Fig.1D), suggesting enrichment for CSCs in LD-ZEB cultures.

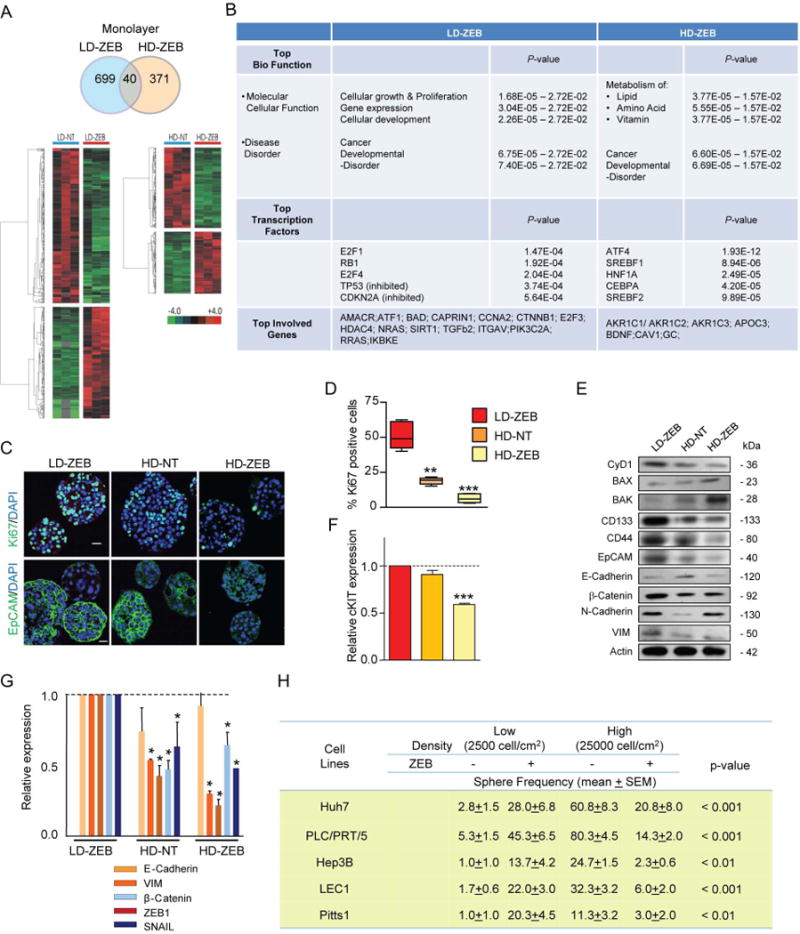

To assess the molecular mechanisms underlying the differential impact of ZEB on hepatic CSC propagation in vitro and in vivo, we examined global genetic alterations caused by ZEB exposure in 2D cultures. A detailed analysis of transcriptome in LD-ZEB and HD-ZEB cells versus corresponding untreated cells (Bootstrap T-test w/10,000 repetitions and ≥ 2 fold changes, P ≤ 0.05) revealed more differentially expressed genes in LD-ZEB (699 genes) than in HD-ZEB (371 genes) cells (Fig. 1A). The biological functions identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) tool in LD-ZEB specific gene signature were involved in cell cycle progression and proliferation (RB1, E2F1-4, CAPRIN1, CCNA2, HDAC4, AMACR, IKBKE), apoptosis repression (BAD), in addition to genes associated with invasion (ATF1, ITGAV), angiogenesis (SIRT1, THBS1) and tumorigenesis (NRAS, RRAS, CTNNB1, TGFβ2, TP53). In addition, several stem/cancer stem cell marker genes including EpCAM, c-MYC, CD2425 and CD13326 were also induced when the threshold cut off was lowered to ≥ 1.5 fold changes (P < 0.05) (Supporting Fig. 2A). The upregulation of these genes was confirmed on the protein levels (Supporting Fig.2B). In stark contrast, the HD-ZEB specific gene signature was characterized by down-regulation of cell cycle related genes (NMYC, CMYC, CDKN1A) and over-presentation of genes associated with lipid (APOC3, AKR1C3, BDNF, CAV1), amino acid (ASNS, ASS1, CD01, GAD1), steroid and vitamin metabolism (AKR1C1/AKR1C2, SERPINA1) (Fig. 1B). This analysis identified a profound influence of cell density on the pattern of genomic alterations caused by a transient ZEB exposure of liver cancer cells.

Fig. 1.

Cell density-dependent effects of a transient ZEB exposure on CSC properties. (A) Venn diagram (top) and heatmaps (bottom) of differentially expressed genes in Huh7 cells plated at low (LD-ZEB) and high (HD-ZEB) density and treated with ZEB for 3 days after normalization to the corresponding untreated cells (n=3 for each condition, 10,000 repetitions in Bootstrap ANOVA with contrast tests and a threshold cut-off of 2-fold change, P<0.05). (B) The IPA analysis of LD-ZEB and HD-ZEB gene signatures (score >40). (C) Representative images of Ki67 and EpCAM immunofluorescence staining in Huh7 primary spheres. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Quantification of Ki67-positive cells (n=3, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus LD-ZEB by ANOVA test with contrast test after inverse normal transformation). (E) Immunoblotting of indicated proteins in Huh7 spheres. β-actin used as a loading control. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of c-KIT expression. GAPDH used as internal control (n=3, ***P<0.001 versus LD-ZEB by Bootstrap t-test with 10,000 repetitions). (G) qRT-PCR analysis of indicated genes in spheres formed by Huh7 cells grown under different culture conditions. The data are means ± SEM (n=3, *P<0.05 versus LD-ZEB cells by Bootstrap t-test with 10,000 repetitions). (H) Effect of ZEB on sphere-forming potential. The data are means ± SEM (n=6, Huh7; n=3, other tumor cell lines, Poisson GLM with multiple comparison test. P-values refer to LD-ZEB versus HD-ZEB).

To provide more direct evidence that demethylation plays a key role in transcriptional reprogramming, we assessed CpG methylation of the promoter region of CD133 chosen as a representative cancer stem cell marker gene with well described changes in methylation pattern upon treatment with demethylating agents.27 The human CD133 gene has two main promoters, P1 and P2, located in a CpG island.28,29 Bisulfite PCR sequencing indicated that the P2 promoter/Exon 1B region of the CD133 gene was largely unmethylated in untreated Huh7 cells, while partial methylation of the P1 promoter region upstream of Exon 1A was observed. The results showed that CD133 promoter region P1 was demethylated in LD-ZEB cells grown both as a monolayer and in a non-adherent condition (Supporting Fig. 1E).

The cell density-dependent diversity in molecular and functional properties of HCC cells was maintained after the drug removal. Thus, the G1-spheres formed by LD-ZEB cells were significantly more proliferative than HD-ZEB or HD-NT spheres as measured by quantification of Ki67 staining (Fig. 1C-D) and increased cyclin D1 expression (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, LD-ZEB spheres expressed higher levels of cancer and stem cell marker proteins (CD133, CD44, EpCAM), and showed upregulation of key genes involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT),14 including SNAIL (Fig. 1E-G).30,31 Conversely, the proapoptotic proteins BAX and BAK were more prevalent in HD-ZEB primary spheres consistent with the microarray analysis (Fig. 1E).

The differential cell density-dependent effects of ZEB on the sphere-forming ability were reproduced in PLC/PRT/5 and Hep3B and two primary HCC-derived cell lines (p.4-6) referred to as LEC1 and Pitts1 (Fig. 1H). We confirmed that in all 5 examined cell lines, ZEB effectively reduced the basal DNMT1 protein levels (Supporting Fig.1F). Thus, a transient treatment of liver cancer cells with a DNA methylation inhibitor could either increase or reduce the number of CSCs depending on the cellular context.

Differences in Long-Term Self-Renewal Capacity

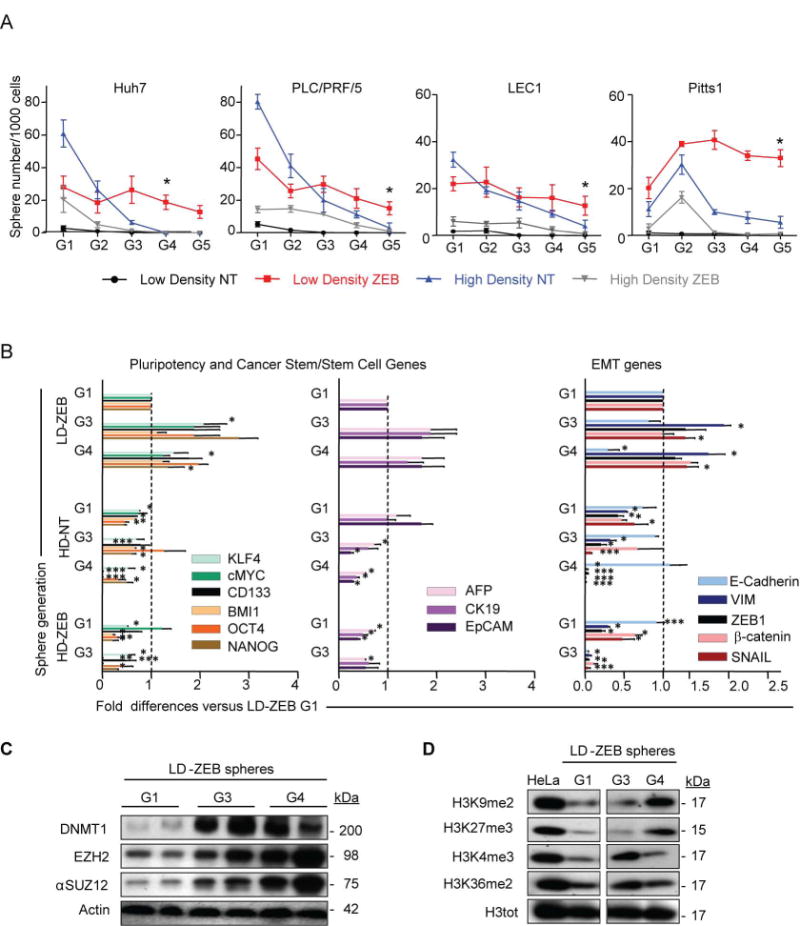

Since only stem cells self-renew, the G1-spheres were dissociated and passaged every 10 days to produce G2-G5 spheres. The assessment of self-renewal in several ZEB-responsive HCC cell lines showed that LD-ZEB cells not only gained the ability to initiate sphere growth in serum-free condition but maintained it for at least 5 generations (Fig. 2A). However, the HD-ZEB and HD-NT cells possessed only a limited lifespan in 3D culture even though the HD-NT Huh7 and PLC/PRF/5 cells were more proficient in G1 sphere generation.

Fig. 2.

Transient DNMT1-inhibition causes sustained functional and molecular alterations in liver cancer cells. (A) Analysis of self-renewal. Primary spheres were passaged every 10 days (generations G1 to G5). The data are means ± SEM (n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by Poisson GLM with multiple comparison test, P-values refer to LD-ZEB versus HD-NT). (B) Gene expression of pluripotency, cancer stem/stem and EMT-related markers by q-RT-PCR (n=3). Data are means ± SEM (n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus LD-ZEB-G1 by Bootstrap t-test with 10,000 repetitions). (C, D) Immunoblotting of indicated proteins in LD-ZEB spheres at different sphere generations. β-actin and H3-total (H3tot) were used as loading controls in C and D, respectively.

Acquisition of long-term self-renewal in LD-ZEB cells strongly correlated with a stable upregulation of key pluripotency (NANOG, OCT4, KLF4, c-MYC), cancer stem/stem cell (CD133, BMI1, EpCAM, etc) and EMT genes (β-Catenin, ZEB1, VIM, SNAL1) starting from G1 (Fig. 2B; Supporting Fig. 3). The latter was paralleled by a progressive downregulation of E-Cadherin, an essential event in EMT, underscoring a selective advantage of EMT traits for self-renewal. Conversely, HD-ZEB and HD-NT spheres were losing the CSC marker genes expression along with sphere passaging (Fig. 2B; Supporting Fig.3).

Notably, LD cells exposed to a short-term ZEB-treatment re-acquired DNMT1 protein and global hypermethylated status at later sphere generations (Fig. 2C). The finding that ZEB depletes the DNMT1 protein via covalent binding rather than inhibition of DNMT1 transcription32 may provide a possible explanation for the persistence of DNMT1 depletion in LD-ZEB-derived G1 spheres. The re-expression of DNMT1 protein was paralleled by upregulation of two repressive histone marks H3K27 and H3K933 associated with DNA hypermethylated genes in adult cancers.34 We also found increased expression of EZH2 and aSUZ12, two components of the Polycomb Repressive Complexes (PRC1 and PRC2) involved in chromatin silencing (Fig. 2D). Recent studies linked EZH2 with DNA methyltransferases and established its role during the induction and targeting of DNA methylation.33 These data suggest that a temporary DNMT1-inhibition may cause sustained alterations in molecular and functional properties of HCC cells which persist long after drug removal and restoration of DNMT1 expression.

Maintenance of Common LD-ZEB Gene Expression Signature

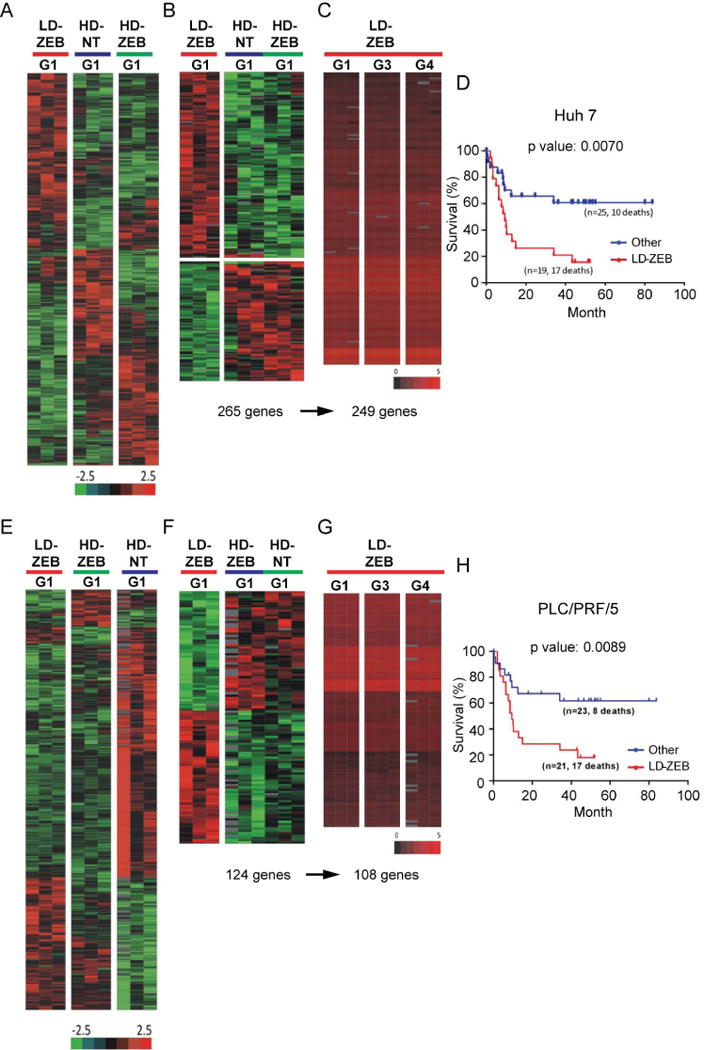

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying differences in self-renewal, spheres formed by LD-ZEB, HD-NT and HD-ZEB cells of Huh7 and PLC/PRF/5 origin were subjected to transcriptomic profiling (Fig. 3A). Significantly, among 265 differentially expressed genes in G1 LD-ZEB spheres formed by Huh7 cells (Fig.3B), 249 genes were commonly deregulated across G1-G4 sphere generations (Fig. 3B-C), demonstrating a remarkable stability and selective advantage of the differentially expressed genes. These included genes involved in proliferation and self-renewal (CCDC6, DCBLD2, DDAH1, IL27RA, HIPK2, GMNN, TCF7L2) as well as cancer progression (PDGFC, TP53, PROM1, IGFR2, DDX17, KDM5A) and invasion (DCBLD2, NARS, NID2, CHN2) whereas genes functionally linked to apoptosis and differentiation (CAPN1, NME2, TAF10) were downregulated (Supporting Table 1). Significant networks identified by IPA analysis (P<10-40) included ERK, NF-kB and TP53 (Supporting Fig.4A) in addition to stem cell signaling associated with PI3K/AKT (not shown). On contrary, HD-NT and HD-ZEB gene expression signatures (163 and 158 genes, respectively) included genes involved in cell death, inflammation and lipid metabolism (Supporting Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Transcriptomic characteristics of tumor-spheres formed by Huh7 (A-D) and PLC/PRF/5 (E-H) cells. (A,E) Heat maps of differentially expressed genes in G1 spheres formed by Huh7 (A) and PLC/PRF/5 (E) cells grown in different conditions. Bootstrap ANOVA with contrast t test (n=3, P<0.05, 10,000 repetitions. (B,F) Supervised hierarchical cluster analysis of LD-ZEB-specific gene signatures identified by a comparison with HD-NT and HD-ZEB in Huh7 (B) and PLC/PRF/5 (F). (C,G) Bioequivalence test of similarities of LD-ZEB specific gene signatures between four consecutive sphere generations in Huh7 (C) and PLC/PRF/5 (G). Data were evaluated at fold change ≤1.5 and P<0.05. (D,H) Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival of HCC patients using Huh7-LD-ZEB 249-gene signature (D) and PLC/PRF/5-LD-ZEB 108-gene signature (H).

The same phenomenon was reproduced in PLC/PRF/5 cells with 108 out 124 genes comprising LD-ZEB sphere-specific gene signature overlapping through G1-G4 (Fig. 3E-G). Despite a limited overlap between Huh7 (Supporting Table 1) and PLC/PRF/5 LD-ZEB (Supporting Table 2) gene signatures, the top deregulated networks were commonly controlled by the same upstream transcriptional regulators NF-kB, ERK, and TP53 or ubiquitin C (UBC), an important regulator of TP53 (Supporting Fig. 4A-B).

We also tested the clinical significance of the LD-ZEB-signatures using our gene expression dataset of 53 human HCCs.24 Both Huh7 and PLC/PRF/5 LD-ZEB gene expression signatures strongly classified HCC patients according to survival and were enriched in the poorly differentiated HCC-A subtype, including tumors defined by hepatic stem cell-like traits and worse clinical outcome (HB, hepatoblast subtype) (Fig. 3D, H).

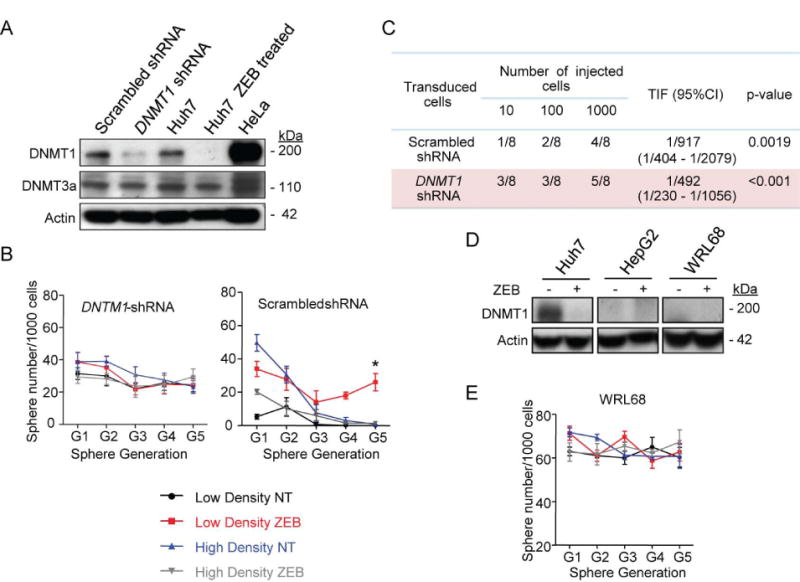

DNMT1 Knockdown Promotes Acquisition of Self-Renewal Ability

To substantiate the role of DNMT1-depletion in cell context-dependent propagation of CSC traits, and to exclude the non-specific effects of ZEB, we carried out DNMT1 loss-of-function experiments in Huh7 cells using lentiviral vector expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against DNMT1. The DNTM1 knockdown caused a stable albeit partial loss of DNMT1 protein as compared to a more effective DNTM1 depletion by a 3-day ZEB exposure. Both genetic and chemical DNMT1 inhibition did not affect the DNMT3a protein levels (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

DNMT1 sh-RNA knockdown in Huh7 cells increases self-renewal potential. (A) Immunoblotting of DNMT1 and DNMT3a. HeLA nuclear extract served as a positive control for DNMT1 expression. β-actin used as a loading control. (B) Sphere frequency at G1-G5 generations. The data are means ± SEM (n=3, ***P<0.001 by Poisson GLM with multiple comparison test). (C) Limiting dilution analysis. The frequency of tumor initiating cells (TIF) and confidence interval (CI95%) were calculated based on the number of resulting tumors/injection site at 10 weeks. (D) Self-renewal of WRL68 cells expressing low basal levels of DNMT1 protein. The data are means ± SEM (n=3, Poisson GLM with multiple comparison test). (E) Immunoblotting of DNMT1. β-actin used as a loading control.

Depletion of DNMT1 protein promoted acquisition of self-renewal in tumor cells plated at low density (Fig. 4B) and significantly increased the frequency of tumor-initiating cells as determined by limiting dilution analysis (Fig. 4C). Self-renewal was maintained across different sphere generations and was independent of the preceding growth conditions and/or ZEB exposure (Fig. 4B).

Transcriptomic profiling of spheroids formed by cells transduced with shRNA against DNMT1 and grown at low (LD-shDNMT1) and high (HD-shDNMT1) density confirmed a strong statistically significant molecular similarity between LD- and HD-shDNMT1 spheres (Pearson R=0.98) (Supporting Fig. 6A). Also high albeit less degree of molecular similarity (R=0.90-0.92) (Supporting Fig.6B) was found between LD-ZEB and LD-shDNMT1 spheres, which was sustained through consecutive sphere generations, again confirming the essential role of DNMT1 depletion in the enhancement of cancer cell stemness properties. The reduced levels of correlation between LD-ZEB and LD-shDNMT1 spheres are most likely due to a contribution of DNMT1-independent effects of ZEB.

Similarly, WRL68 and HepG2 hepatoblastoma cell lines expressing low basal levels of DNMT1 (Fig. 4D) also possessed a high self-renewal irrespective of cell density or ZEB exposure (Fig. 4E). Thus, experimentally lowered levels of DNMT1 protein achieved either by a gene silencing (Fig. 4C) or transient ZEB treatment (Fig. 2A) promoted de novo acquisition of self-renewal. The cells transiently treated with ZEB sustained this function even after restoration of the DNMT1 expression (Fig. 2C).

LD-ZEB Spheres are More Tumorigenic

Finally, to assess the ability of LD-ZEB, HD-ZEB, and HD-NT spheres to generate tumors, G1 spheres formed by Huh7, PLC/PRF/5, and Pitts1 cells were dissociated and injected subcutaneously in NOD/SCID mice (Fig. 5A). In agreement with the enhanced self-renewal in vitro (Fig. 2), LD-ZEB sphere-cells were more tumorigenic in all three examined cell lines and engrafted 75-80% transplanted mice (Fig. 5A). In contrast, HD-ZEB-spheres produced significantly less or no tumors within 5 weeks of observation and therefore were excluded from further analysis.

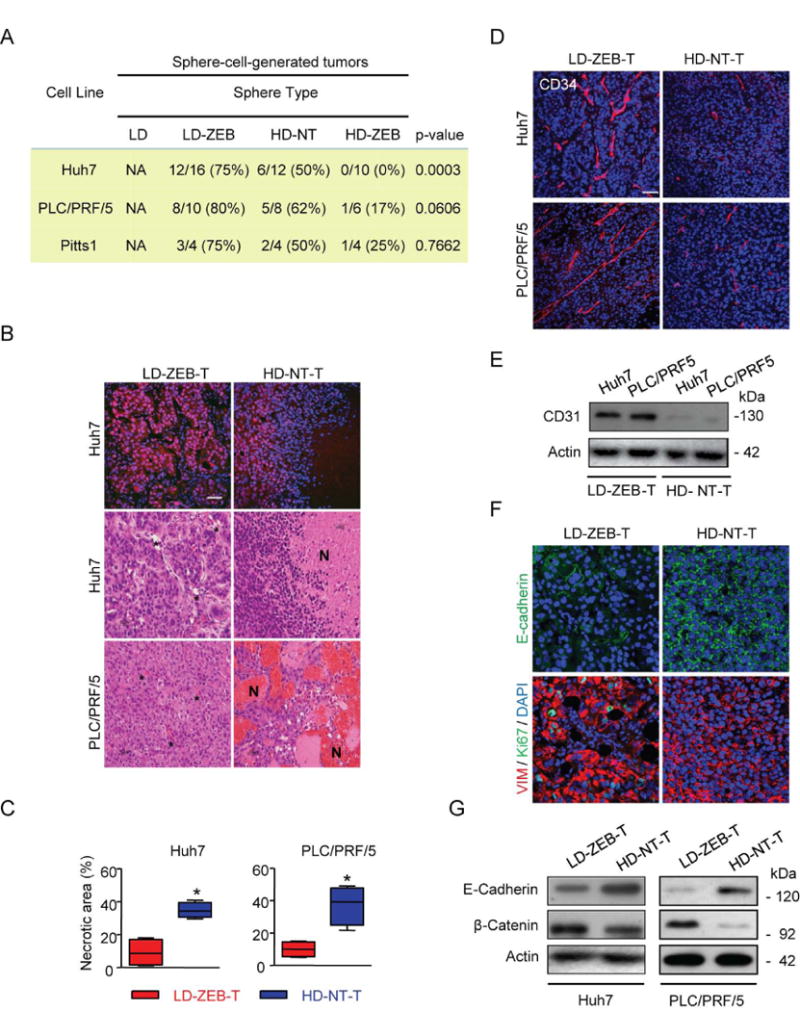

Fig. 5.

Effects of a transient DNMT1 Inhibition on tumorigenicity. (A) The frequency of sphere-cell-generated tumors at 10 weeks after subcutaneous injection of 100 cells into NOD/SCID mice. Shown are the numbers of tumors per injection site. Fisher's exact test was applied to evaluate statistical significance. (B) Representative H&E and PCNA immunofluorescence staining on paraffin-embedded tumor sections. (C) Quantification of necrotic areas on tumor sections stained with H&E (n=4, *P<0.05 by Bootstrap t-test with 10,000 repetitions after inverse normal transformation). (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of CD34 staining. (E) Immunoblotting of CD31. β-actin used as a loading control. (F) Representative immunofluorescence staining with anti-E-cadherin and double immunofluorescence staining with anti-vimentin and anti-Ki67. (G) Western blot analysis of E-Cadherin and β-Catenin. β-actin used as a loading control. Scale bar, 50 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI (B, upper images, D and F).

Although primary sphere forming ability of HD-NT and LD-ZEB cells was comparable (Pitts1) or even higher (Huh7, PLC/PRF/5) (Fig. 2A), HD-NT-sphere-cells initiated less tumors than LD-ZEBs supporting that tumorigenic potential is not necessarily dependent on sphere-phenotype.35 Even more striking differences were found upon subsequent histopathological evaluation of tumors. Tumors generated by LD-ZEB-sphere cells (LD-ZEB-T) were more proliferative and displayed typical HCC cytoarchitecture with a prominent vasculature whereas tumors initiated by HD-NT-sphere cells (HD-NT-T) were smaller, lacked stroma, and showed a higher propensity to necrotic death, likely a result of the reduced vascularity (Fig. 5B,D-E). Cell tracking experiments using a clonal Huh7 cell line transduced with lentiviral vector expressing green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and luciferase (Huh7EGFF+/Luc+) combined with GFP and CD34 staining confirmed the host origin of blood vessels excluding a possibility of vascular mimicry effect (Supporting Fig.7A).

The Huh7EGFF+/Luc+ reporter cell line was also used to monitor the kinetics of tumor growth and metastatic potential. Ex vivo bioluminescence imaging revealed more frequent metastasis into lung and brain in mice injected with LD-ZEB cells (Supporting Fig.7B-C). Accordantly, LD-ZEB-T displayed a more prominent EMT phenotype as determined by the increased expression of vimentin (VIM) and repression of E-Cadherin (Fig.5F-G) as compared to HD-NT-T. In contrast to LD-ZEB cells, HD-ZEB progressively loose tumorigenicity from G1 to G4 reflecting the functional exhaustion of CSCs (Fig. 6A)

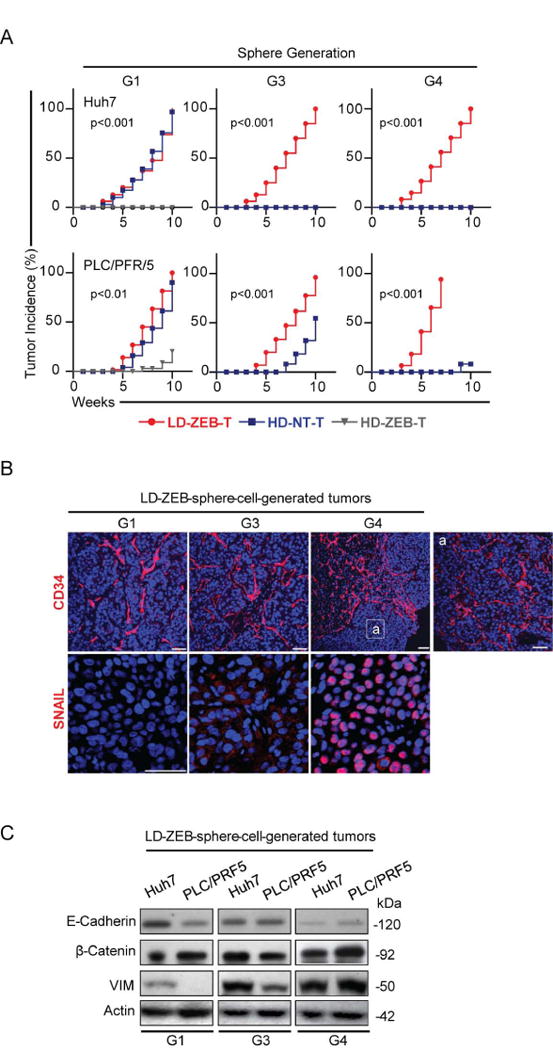

Fig. 6.

Increased tumorigenicity with sphere passaging. (A) Kinetics of tumor growth in NOD/SCID mice after subcutaneous injection of 100 tumor cells isolated from the indicated spheres at generations G1, G3 and G4. P-values evaluated by log rank test refer to LD-ZEB versus HD-NT. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of CD34 and SNAIL staining. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Immunoblotting of indicated proteins. β-actin used as a loading control.

Tumors derived from G1-G4 LD-ZEB spheres were increasingly more vascular and gained nuclear SNAIL, a key transcriptional repressor of E-Cadherin, promoting invasion and tumor metastasis36 (Fig. 6B-C). These data suggest selection for more aggressive subsets of CSCs during serial sphere passaging.

Discussion

Tumor phenotypes reflect the interaction of distinct genetic and epigenetic changes with tumor microenvironment. Here we provide evidence for an opposite molecular and functional reprogramming of hepatic CSC in vitro in response to a transient inhibition of DNMT1. The duality of this action was dependent on the cellular density, and could either promote or suppress acquisition of CSC properties and malignancy.

To recapitulate the in vivo tumor microenvironment, a 3D-culture system has been widely used to identify, enrich and expand the self-renewing cell populations. The spheres generated by tumor cells which were cultured and treated with ZEB at different cell densities exhibited remarkably diverse functional and molecular properties. Only LD-ZEB-derived spheres showed the acquisition of stemness potential as evidenced by in vitro “serial-sphere assay” and enhanced tumor initiating ability. Conversely, 3D-HD-ZEB cells displayed reduced stemness hallmarks, failed to support the serial-sphere propagation and possessed a reduced tumor initiating potential as compared to 3D-LD-ZEB cells. These findings indicate that cellular density is a critical determinant in the response of liver cancer cells to demethylation agents. Supporting this notion, we found striking differences in the global gene expression profiles between the LD-ZEB and HD-ZEB cells both in 2D and 3D conditions. The dominant LD-ZEB gene-networks reflected the acquisition of stemness properties and increased malignancy whereas genes regulating apoptosis and differentiation were down-regulated. The phenotypic and genomic changes induced in LD-ZEB condition were long lasting despite a recovery of DNMT1 expression, indicating the persistence of epigenetic memory traits. These data concur with a recent work by Tsai et al. 37 The authors elegantly demonstrated that a transient exposure of cultured and primary leukemic and epithelial tumor cells to clinically relevant nontoxic nanomolar doses of DNA methylation inhibitors decitabine and azacitidine produced a long-lasting antitumor “memory” response, including inhibition of subpopulations of cancer stem-like cells. Similarly, ZEB treatment of HCC cells under the HD condition exerted a “therapeutic effects” as reflected by a reduced CSC frequency and tumorigenicity, and up-regulation of genes involved in cell death.

The experiments with shRNA-mediated knockdown of DNMT1 provided some insights into the mechanism(s) responsible for the diverse epigenetic reprogramming of liver cancer cells. A strong down-regulation of DNMT1 expression (about 90%) resulted in a stable acquisition of the “LD-ZEB phenotype” independent of culture conditions or ZEB treatment. Significantly, the DNMT1 shRNA-treated cells and LD-ZEB cells acquired highly similar transcriptomic changes. Furthermore, two hepatoblastoma cell lines (WRL68 and HepG2) which expressed low basal levels of DNMT1 protein also displayed extended self-renewal in vitro and insensitivity to ZEB-induced reprogramming. Consistent with the “duality” of ZEB action exerting either oncogenic or proapoptotic effects depending on the drug-sensitivity of liver cancer cells32, we now report on a further sub-classification of the ZEB-response in the sensitive HCC cell lines into LD-ZEB oncogenic- and HD-ZEB therapeutic-promoting responses, respectively.

The remarkable differences in biology and histopathology between LD-ZEB and HD-ZEB sphere-cell-generated tumors support the long-term epigenetic reprogramming and emergence of new tumor phenotypes. The low tumorigenicity of HD-ZEB-spheres as compared to the HD-NT counterparts stands in a stark contrast to the high tumor and metastatic potential of LD-ZEB-3D-cells. In particular, the acquisition of metastatic capacity of the LD-ZEB-sphere-derived cells substantiates the malignant cell reprogramming. A detailed analysis of the underlying molecular mechanism(s) is needed to provide the base knowledge for effective prevention and/or treatment of this malignant phenotype.

In summary, three major findings emerged from our study of the selective DNMT1 inhibition with ZEB in established and primary human HCC cell lines. First, the cellular context is a critical determinant in the response to DNMT1 inhibition resulting in a long term epigenetically driven reprogramming which can exert both pro- and anti-tumor effects. Second, a permanent reduction of DNMT1 protein level renders the HCC cell lines insensitive to both DNMT1 inhibition and cellular context. Third, DNA methylation may be a key epigenetic regulatory mechanism determining the CSC pool in liver cancer and possibly other solid tumors. These data may also be relevant in the context of a broad applicability of DNA demethylating agents in cancer management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. A. Conner for help with animal procedures, B. Taylor and S. Banerjee for assistance with flow cytometry, and T. Hoang for help with immunohistochemistry.

Financial support: The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National CancerInstitute, Center for Cancer Research.

List of Abbreviations

- CSC

Cancer Stem Cells

- DNMT1

DNA methyltransferase1

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ZEB

Zebularine

Footnotes

Transcript profiling: GEO accession number: GSE47932

Disclosures: The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Almendro V, Marusyk A, Polyak K. Cellular heterogeneity and molecular evolution in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:277–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-163923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magee JA, Piskounova E, Morrison SJ. Cancer stem cells: impact, heterogeneity, and uncertainty. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.You JS, Jones PA. Cancer genetics and epigenetics: two sides of the same coin? Cancer Cell. 2012;22:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng X, Blumenthal RM. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases: a structural perspective. Structure. 2008;16:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikkelsen TS, Hanna J, Zhang X, Ku M, Wernig M, Schorderet P, Bernstein BE, et al. Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature. 2008;454:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nature07056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruau D, Ensenat-Waser R, Dinger TC, Vallabhapurapu DS, Rolletschek A, Hacker C, Hieronymus T, et al. Pluripotency associated genes are reactivated by chromatin-modifying agents in neurosphere cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:920–926. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marquardt JU, Raggi C, Andersen JB, Seo D, Avital I, Geller D, Lee YH, et al. Human hepatic cancer stem cells are characterized by common stemness traits and diverse oncogenic pathways. Hepatology. 2011;54:1031–1042. doi: 10.1002/hep.24454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Carvalho DD, You JS, Jones PA. DNA methylation and cellular reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connelly JT, Gautrot JE, Trappmann B, Tan DW, Donati G, Huck WT, Watt FM. Actin and serum response factor transduce physical cues from the microenvironment to regulate epidermal stem cell fate decisions. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:711–718. doi: 10.1038/ncb2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bissell MJ, Inman J. Reprogramming stem cells is a microenvironmental task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15637–15638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808457105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrader J, Gordon-Walker TT, Aucott RL, van Deemter M, Quaas A, Walsh S, Benten D, et al. Matrix stiffness modulates proliferation, chemotherapeutic response, and dormancy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2011;53:1192–1205. doi: 10.1002/hep.24108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trappmann B, Gautrot JE, Connelly JT, Strange DG, Li Y, Oyen ML, Cohen Stuart MA, et al. Extracellular-matrix tethering regulates stem-cell fate. Nat Mater. 2012;11:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nmat3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connelly JT, Mishra A, Gautrot JE, Watt FM. Shape-induced terminal differentiation of human epidermal stem cells requires p38 and is regulated by histone acetylation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Beyec J, Xu R, Lee SY, Nelson CM, Rizki A, Alcaraz J, Bissell MJ. Cell shape regulates global histone acetylation in human mammary epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3066–3075. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimlin LC, Casagrande G, Virador VM. In vitro three-dimensional (3D) models in cancer research: an update. Mol Carcinog. 2013;52:167–182. doi: 10.1002/mc.21844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ponti D, Costa A, Zaffaroni N, Pratesi G, Petrangolini G, Coradini D, Pilotti S, et al. Isolation and in vitro propagation of tumorigenic breast cancer cells with stem/progenitor cell properties. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5506–5511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, Fullen DR, Johnson TM, Morrison SJ. Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature. 2008;456:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature07567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuhauser M, Jockel KH. A bootstrap test for the analysis of microarray experiments with a very small number of replications. Appl Bioinformatics. 2006;5:173–179. doi: 10.2165/00822942-200605030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen JB, Loi R, Perra A, Factor VM, Ledda-Columbano GM, Columbano A, Thorgeirsson SS. Progenitor-derived hepatocellular carcinoma model in the rat. Hepatology. 2010;51:1401–1409. doi: 10.1002/hep.23488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen JB, Factor VM, Marquardt JU, Raggi C, Lee YH, Seo D, Conner EA, et al. An integrated genomic and epigenomic approach predicts therapeutic response to zebularine in human liver cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:54ra77. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee TK, Castilho A, Cheung VC, Tang KH, Ma S, Ng IO. CD24(+) liver tumor-initiating cells drive self-renewal and tumor initiation through STAT3-mediated NANOG regulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO, Zheng BJ, et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–56. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.You H, Ding W, Rountree CB. Epigenetic regulation of cancer stem cell marker CD133 by transforming growth factor-beta. Hepatology. 2010;51:1635–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.23544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabu K, Sasai K, Kimura T, Wang L, Aoyanagi E, Kohsaka S, Tanino M, et al. Promoter hypomethylation regulates CD133 expression in human gliomas. Cell Res. 2008;18:1037–1046. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pleshkan VV, Vinogradova TV, Sverdlov ED. Methylation of the prominin 1 TATA-less main promoters and tissue specificity of their transcript content. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez-Losada J, Sanchez-Martin M, Perez-Caro M, Perez-Mancera PA, Sanchez-Garcia I. The radioresistance biological function of the SCF/kit signaling pathway is mediated by the zinc-finger transcription factor Slug. Oncogene. 2003;22:4205–4211. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Caro M, Bermejo-Rodriguez C, Gonzalez-Herrero I, Sanchez-Beato M, Piris MA, Sanchez-Garcia I. Transcriptomal profiling of the cellular response to DNA damage mediated by Slug (Snai2) Br J Cancer. 2008;98:480–488. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng JC, Yoo CB, Weisenberger DJ, Chuang J, Wozniak C, Liang G, Marquez VE, et al. Preferential response of cancer cells to zebularine. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vire E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, Morey L, et al. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature. 2006;439:871–874. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGarvey KM, Fahrner JA, Greene E, Martens J, Jenuwein T, Baylin SB. Silenced tumor suppressor genes reactivated by DNA demethylation do not return to a fully euchromatic chromatin state. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3541–3549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett LE, Granot Z, Coker C, Iavarone A, Hambardzumyan D, Holland EC, Nam HS, et al. Self-renewal does not predict tumor growth potential in mouse models of high-grade glioma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai HC, Li H, Van Neste L, Cai Y, Robert C, Rassool FV, Shin JJ, et al. Transient low doses of DNA-demethylating agents exert durable antitumor effects on hematological and epithelial tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:430–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.