Abstract

Inadequate patient engagement in hospital care inhibits high quality care and successful transitions to home. Tablet computers may provide opportunities to engage patients, particularly during inactive times between provider visits, tests, and treatments, by providing interactive health education modules as well as access to their Personal Health Record (PHR). We conducted a pilot project to explore inpatient satisfaction with bedside tablets and barriers to usability. Additionally, we evaluated use of these devices to deliver 2 specific web-based programs: 1) an interactive video to improve inpatient education about hospital safety; 2) Personal Health Record access to promote inpatient engagement in discharge planning.

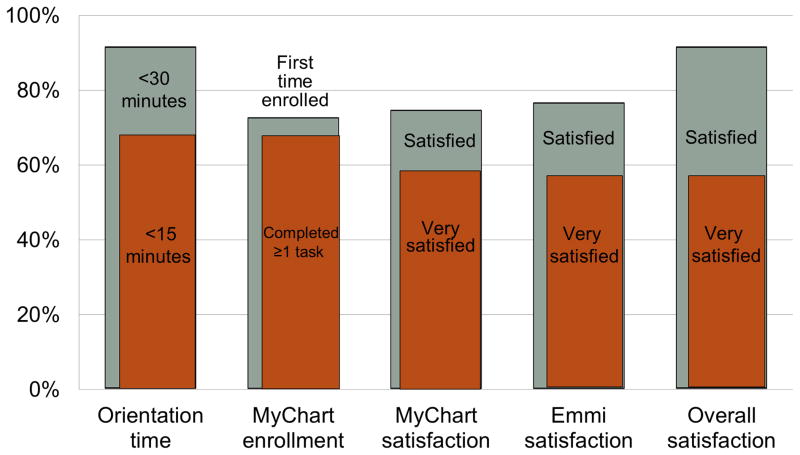

We enrolled 30 patients: 17 (60%) age 40 or older, 17 (60%) women, 17 (60%) owned smartphones, and 6 (22%) owned tablet computers. Twenty-seven (90%) reported high overall satisfaction with the device and 26 (87%) required ≤30 minutes for basic orientation (70% required ≤15min). Twenty-five (83%) independently completed an interactive educational module on hospital patient safety. Twenty-one (70%) accessed their PHR to view their medication list, verify scheduled appointments, or send a message to their PCP. Next steps include education on high-risk medications, assessment of discharge barriers, and training clinical staff (such as RTs, RNs, or NPs) to deliver tablet interventions.

Keywords: mobile health, tablet computers, personal health records, patient-centered care, hospital care, transitions in care

Background

Many hospitals have initiated intense efforts to improve transitions of care1 such as discharge coordinators or transition coaches2, 3 but uses of mobile devices as approaches to add or extend the value of human interventions have been understudied.4 Additionally, many hospitalized patients experience substantial inactive time between provider visits, tests, and treatments. This time could be used to engage patients in their care through interactive health education modules and by learning to use their personal health record (PHR) to manage medications and post-discharge appointments.

Greater understanding of the advantages and limitations of mobile devices may be important for improving transitions of care and may help leverage existing hospital personnel resources. However, prior studies have focused on healthcare provider uses of tablet computers for medical education,5 to collect clinical registration data,6 or to do clinical work (e.g. check labs, write notes)7,8,9 primarily in outpatient settings; few studies have focused on patient uses for this technology in hospital settings.10, 11 To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a pilot project to explore inpatient satisfaction with bedside tablets and barriers to usability.

Additionally, we evaluated use of these devices to deliver 2 specific web-based programs: 1) an interactive video to improve inpatient education about hospital safety; 2) Personal Health Record access to promote inpatient engagement in discharge planning.

Methods

Study design, patient selection, and devices/programs

We conducted a prospective study of tablet computers to engage patients in their care and discharge planning through web-based interactive health education modules and use of PHRs. We used 2 tablets, distributed daily by research assistants (RAs) to eligible patients after morning rounds. Inclusion criteria for patients were ability to speak English and admission to the medical (hospitalist) service at UCSF Medical Center. Exclusion criteria were ICU admission, contact isolation, or inability to complete the consent process due to altered mental status or cognitive impairment.

RAs screened patients for inclusion/exclusion via the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and then approached them after rounds for enrollment (11am–1pm). RAs then performed a tiered orientation tailored to individual patient experience and needs. First, they deliver a brief tutorial focused on the tablet itself and its basic functions (touchscreen, keypad, and Internet browser use). Second, RAs showed patients how to access the online educational health module and how to navigate content within the module. Finally, RAs explained what the PHR is and demonstrated how to login, how to navigate tabs within the PHR, and how to perform basic tasks (view/refill medications, view/modify appointments, and view/send messages to providers). The RAs left devices with patients for 3–5 hours and returned to collect them and perform debrief interviews. After each device was returned, RAs cleaned devices with disinfectant wipes available in patient rooms and checked for physical damage or software malfunctions (e.g. unable to turn on or unlock). Finally, RAs used the reset function to erase any personal data or setting modifications made by patients and docked the devices overnight to re-sync original settings and recharge batteries.

We used Apple iPad2 (16 gigabyte) without any enclosures, cases, or security devices. Our educational health module was “Patient Safety in the Hospital” which was professionally developed by Emmi Solutions (www.emmisolutions.com) and licensed to our medical center for use in patient care. The module presents topics with a combination of animated graphics and text that is narrated and customizable to patient preferences (faster, slower, more/less info). The content areas covered in this module are medication history and safety, communicating with the healthcare team, advanced directives, hand-washing, fall prevention, and discharge planning. This content is developed by Emmi Solutions with clinician and patient input (with a wide range of health experiences and literacy) and is available in English and Spanish. Our PHR platform is Epic MyChart (http://www.epic.com/software-phr.php).

Survey instruments and data collection

We developed pre- and post-intervention surveys to characterize patients’ demographics, device ownership, and health-related Internet activities in the last year based on questions used in the CDC National Health Interview Study (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm). Both surveys were administered on the tablets using online survey tools (www.surveymonkey.com). We also developed an interview tool which collected information on time needed to orient patients, problems with devices, and open-ended questions about overall experience using the tablet. During the debrief interview, RAs observed patient ability to access their PHR and perform key functions (view medication list, view future appointments, or message a provider). Data from the debrief interview were entered into a HIPAA-compliant online survey tool (http://project-redcap.org) via the tablet by the RA at bedside.

Analyses

We used frequency analysis to describe patient demographics, ability to complete online health educational modules, and utilization of their PHR. We performed bivariate analyses (Fisher’s exact test) to assess correlations between demographics (age, device ownership, Internet use) and key pilot program performance measures (orientation time ≤15min, online health module completion, and completion of ≥1 essential function in the PHR). All analyses were performed in SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC). The Institutional Review Board of record for UCSF approved this study.

Results

As shown in Table 1, we enrolled 30 patients. Most participants (60%) were age 40 or older and most (87%) owned a mobile device: 70% owned a laptop and 60% owned a smartphone but few (22%) owned a computer tablet. Most participants accessed the Internet daily but fewer reported Internet use for health tasks: about half (52%) communicated with a provider but few refilled a prescription (27%) or scheduled an appointment (21%) online over the last year.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| N=30 | Number (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (yrs) | |

| 18–39 | 11 (38%) |

| 40–49 | 5 (18%) |

| 50–59 | 4 (14%) |

| 60–69 | 5 (18%) |

| 70–79 | 3 (10%) |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Female | 17 (60%) |

|

| |

| Device ownership | |

| Desktop computer | 12 (44%) |

| Laptop computer | 19 (70%) |

| Smart phone | 17 (60%) |

| Tablet computer | 6 (22%) |

| Any mobile device (laptop, smartphone, or tablet) | 26 (87%) |

|

| |

| Internet use | |

| Daily | 21 (72%) |

| Several times a week | 3 (10%) |

| Once a week or less | 5 (18%) |

|

| |

| Pre-study online health tasks | |

| Looked up health info | 21 (72%) |

| Communicated with provider | 15 (52%) |

| Refilled prescription | 8 (27%) |

| Scheduled medical appointment | 6 (21%) |

Nearly all participants (90%) were satisfied or very satisfied with their experience using the tablet in the hospital (Figure 1). Most (87%) required 30 minutes or less for basic orientation and 70% required only 15 minutes or less. Most participants (83%) were able to independently complete an interactive health education module on hospital safety and were highly satisfied with the module. Despite the fact that 73% of participants were a first time user of our PHR, the majority was able to login and independently access their medication list, verify scheduled appointments, or send a secure message to their primary care provider.

Figure 1.

Performance Measures

Participants age 50 or older were less likely to complete orientation in 15 minutes or less compared to those under 50 (25% vs. 79%, p-value=0.025); however, age was not a significant factor in ability to complete the online health educational module or perform at least one essential PHR function. Other demographic features such as device ownership and daily Internet use did not correlate with shorter orientation time, educational module completion, or PHR use (data available on request).

Participants also made suggestions for improvement during the debrief interviews. Several suggested applications for entertainment (gaming, magazines, or music) and two suggested that all patients should be introduced to their PHR during hospitalization (data available on request). No device software malfunction (e.g. device freezes, Internet connection failures), hardware issues (e.g. damage from falls, wetness, or repeated disinfectant exposure), theft or misappropriation was reported by patients or observed by the RAs to date.

Discussion

Our pilot study suggests that tablet-based access to educational modules and personal health records can increase inpatient engagement in care with high satisfaction and minimal time for orientation. Surprisingly, even older patients and those who might be considered less “tech savvy” in terms of Internet use and device ownership were equally able to utilize our tablet interventions. Furthermore, we did not experience any hardware issues in the harsh physical environment of inpatient wards. These preliminary finding suggest the potential utility of tablets for clinically-meaningful tasks by inpatients with a low rate of technical issues.

From a technical standpoint, our experience suggests several next steps. First, although orientation time was minimal, it might be even less if patients used their own mobile devices since most patients already owned one. This “BYOD” (Bring Your Own Device) approach could also promote post-discharge patient engagement. Second, the flexibility of a BYOD approach raises the question of whether to also allow patients a choice of application-based vs. browser-based platforms for specific programs such as the PHR and educational video we used. Indeed, while we used a browser-based approach, several other teams have developed patient-facing engagement applications (or “apps”) for mobile devices4, 12 and hospitalists could “prescribe” apps at discharge as a more providers are now doing in outpatient settings.13 Of course, maximizing flexibility for BYOD and web-based vs. app-based approaches would likely increase patient engagement but would come at the cost of more time and effort for hospital providers to vet apps/websites and educate patients about their use. Third, regardless of the devices and programs used, broader engagement of patients, nurses, hospitalists and other providers will be needed in the future to identify key areas for development to avoid over-burdening patients and providers.

From a quality improvement perspective, recent literature has considered broad clinical uses for tablets by hospital providers14,15 but our experience suggests more specific opportunities to improve transitions of care though direct patient engagement. Tablets and other mobile devices may help improve discharge education for patients taking high-risk medications such as warfarin or insulin using interactive educational modules similar to hospital safety modules we used. Additionally, clinical staff such as nurses and pharmacists can be trained to deliver mobile device interventions such as education on high-risk medications.16 Ultimately, scale up for our intervention will require that mobile devices and content eventually improve and replace current practices by hospital staff (especially nurses) in a way that streamlines, rather than compounds current workflow. This could increase efficiency in these discharge tasks and extend contributions of these providers to high quality transitions.

Our study has several limitations. First, while this is a pilot study with only 30 patients, it adds needed scale to much smaller (N=5–8) published feasibility studies of tablet computer use by inpatients.11, 12 Beyond more robust feasibility testing, our study adds new data about mobile device use for specific clinical tasks in the hospital such as patient education and PHR use. Second, we did not track post-discharge outcomes to test effects of our intervention on transition care quality; this will be a focus of our future research. Third, we used existing platforms for interactive educational modules and PHR access at our site; participant satisfaction in our study may not generalize to other platforms. Furthermore, most PHR platforms (including ours) are not optimally-configured to engage patients during transitions of care but we plan to integrate existing functions (such as ability to refill medications or change appointments) into discharge education and planning. Finally, we have not engaged caregivers as surrogates for cognitively-impaired patients or adapted our platform for non-English speakers; these are areas for development in our ongoing work. Overall, our pilot results help set the stage to deploy mobile devices for better patient monitoring, engagement, and quality of care in the inpatient setting.17

In conclusion, our pilot project demonstrates that tablet computers can be used to improve inpatient education and patient engagement in discharge planning. Inpatients are highly satisfied with the use of tablets to complete health education modules and access their PHR with minimal time required for patient training and device management by hospital staff. Tablets and other mobile devices have significant potential to improve patients’ education and engagement in their hospital care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the UCSF mHealth group and Center for Digital Health Innovation for advice and for providing tablet computers for this pilot project.

Dr. Auerbach was supported by grant K24HL098372 (NHLBI). Dr. Greysen was supported by a career development award (KL-2) from the UCSF Clinical Translational Sciences Institute (CTSI).

Footnotes

This paper was presented as a Finalist in the RIV Competition (Innovations Category) the 2013 Annual Meeting of the Society for Hospital Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have declared they have no financial, personal, or other conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

References

- 1.Kocher RP, Adashi EY. Hospital readmissions and the Affordable Care Act: paying for coordinated quality care. JAMA. 2011 Oct 26;306(16):1794–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A Reengineered Hospital Discharge Program to Decrease Re-hospitalization. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S. The Care Transitions Intervention: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–28. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Project RED. [Accessed on July 12, 2013];Meet Louise… and Virtual Patient Advocates. at: http://www.bu.edu/fammed/projectred/publications/VirtualPatientAdvocateWebsiteInfo2.pdf.

- 5.Kho A, Henderson LE, Dressler DD, Kripalani S. Use of handheld computers in medical education. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 May;21(5):531–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy KC, Wong FL, Martin LA, Edmiston D. Ongoing evaluation of ease-of-use and usefulness of wireless tablet computers within an ambulatory care unit. Stud Health Tech Inform. 2009;143:459–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cockerham M. Use of a tablet personal computer to enhance patient care on multidisciplinary rounds. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009 Nov 1;66(21):1909–11. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCreadie SR, McGregory ME. Experiences incorporating Tablet PC’s into clinical pharmacists’ workflow. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2005 Fall;19(4):32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prgomet M, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI. The impact of mobile handheld technology on hospital physicians’ work practices and patient care: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009 Nov-Dec;16(6):792–801. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalil Madathil K, Koikkara R, Obeid J, et al. An investigation of the efficacy of electronic consenting interfaces of research permissions management system in a hospital setting. Int J Med Inform. 2013 Jun 8; doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.04.008. pii:S1386-5056(13)00104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley AC, Benoit A, Chang F, Pozzar R, Caligtan CA. Building and testing a patient-centric electronic bedside communication center. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013 Jan;39(1):15–9. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20121204-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lippman H. How apps are changing family medicine. J Fam Pract. 2013 Jul;62(7):362–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger E. The iPad: gadget or medical godsend? Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Jul;56(1):A21–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marceglia S, Bonacina S, Zaccaria V, et al. How might the iPad change healthcare? J R Soc Med. 2012 Jun;105(6):233–41. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2012.110296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King CA. Keeping the patient focus: using tablet technology to enhance education and practice. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2012 Jun;43(6):249–50. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20120523-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilsen W, Kumar S, Shar A, et al. Advancing the science of mHealth. J Health Commun. 2012;17(Suppl 1):5–10. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.677394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.