Abstract

In this study, we examined the impact of rapamycin on mTORC1 signaling during 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced keratinocyte proliferation and skin tumor promotion in both wild-type (FVB/N) and BK5.AktWT mice. TPA activated mTORC1 signaling in a time-dependent manner in cultured primary mouse keratinocytes and a mouse keratinocyte cell line. Early activation (15–30 min) of mTORC1 signaling induced by TPA was mediated in part by PKC activation, whereas later activation (2–4 h) was mediated by activation of EGFR and Akt. BK5.AktWT transgenic mice, where Akt1 is overexpressed in basal epidermis, are highly sensitive to TPA-induced epidermal proliferation and two-stage skin carcinogenesis. Targeting mTORC1 with rapamycin effectively inhibited TPA-induced epidermal hyperplasia and hyperproliferation as well as tumor promotion in a dose-dependent manner in both wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice. A significant expansion (∼threefold) of the label retaining cell (LRC) population per hair follicle was observed in BK5.AktWT mice compared to FVB/N mice. There was also a significant increase in K15 expressing cells in the hair follicle of transgenic mice that coincided with expression of phospho-Akt, phospho-S6K, and phospho-PRAS40, suggesting an important role of mTORC1 signaling in bulge-region keratinocyte stem cell (KSC) homeostasis. After 2 weeks of TPA treatment, LRCs had moved upward into the interfollicular epidermis from the bulge region of both wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice. TPA-mediated LRC proliferation and migration was significantly inhibited by rapamycin. Collectively, the current data indicate that signaling through mTORC1 contributes significantly to the process of skin tumor promotion through effects on proliferation of the target cells for tumor development.

Keywords: mTOR, Akt, rapamycin, bulge-region stem cell, tumor promotion, TPA

Introduction

The PI3K/Akt pathway is one of the most commonly altered pathways in human tumors [1–3]. Despite the established association between deregulated Akt signaling and cancer, the downstream molecules that directly mediate the effects of aberrant Akt signaling on tumorigenesis have yet to be clearly defined. Recent evidence indicates a crucial role for elevated mammalian target of rapamycin complex1 (mTORC1) signaling in mediating at least some of the effects of aberrant Akt signaling on cancer development [4,5].

mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase that regulates protein synthesis, cell growth, and proliferation [6]. mTOR exists in two complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2 [7]. mTORC1 is the mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin and controls cell growth by regulation of protein synthesis primarily through its downstream effectors, S6K and 4EBP1 [8]. Although initially insensitive to rapamycin, prolonged or chronic treatment results in inhibition of mTORC2. Once activated, mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt at serine 473 [9]. Recently, mTOR has been identified as a critical mediator of tumorigenesis, making this molecule an important target for both cancer chemo-prevention and treatment [10,11]. Rapamycin, a well-characterized mTORC1 inhibitor, has been shown to have significant tumor suppressing effects in several preclinical xenograft models [12–14] as well as other mouse models of UV-, chemically-, or transgene-induced tumor development [15–17].

In the mouse skin model of multistage epithelial carcinogenesis, Akt activation increases as tumors progress from premalignant papillomas to malignant squamous cell carcinomas [18]. Previously, we discovered that Akt activation is an important event during the very early stages of skin tumor promotion by diverse tumor promoters [19,20]. Both the early and the sustained activation of Akt in mouse keratinocytes appeared to be due primarily to activation of the EGFR. In addition, several downstream Akt targets were found to be modulated in keratinocytes during tumor promotion, including glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β, Bad, and mTOR, suggesting a role for one or more of these downstream pathways in the process of tumor promotion [19,20]. In further studies, transgenic mice overexpressing either wild-type Akt1 (AktWT) or a constitutively active (i.e., myristoylated) form of Akt1 (Aktmyr) in epidermal basal cells under control of the bovine keratin 5 (BK5) promoter exhibited dramatically enhanced susceptibility to skin tumor promotion [20]. Enhanced susceptibility of these mice was associated with elevated mTORC1 signaling, subsequent elevation of cell cycle regulatory proteins and an enhanced epidermal proliferation following TPA treatment.

In the current study, we demonstrate that activation of mTORC1 by TPA in mouse keratinocytes occurs in a temporal manner, initially involving PKC activation and subsequently involving Akt activation via the EGFR. In addition, sustained activation of mTORC1 in keratinocytes following topical application of TPA occurs primarily via sustained activation of the EGFR and PI3K/Akt. Using a transgenic mouse model with targeted expression of a wild-type form of Akt1 in epidermal basal cells (BK5.AktWT), topical application of rapamycin 30 min prior to TPA treatment inhibited mTORC1 signaling and significantly inhibited TPA-induced epidermal hyperplasia and proliferation in a dose-dependent manner in both nontransgenic and BK5.AktWT transgenic mice, although rapamycin was less effective on a dose basis in the BK5.AktWT mice. Furthermore, increased expression of Akt1 led to a significant increase in the number of label retaining cells (LRCs) in the hair follicle bulge region of the transgenic mice and an increase in the number of cells expressing K15, as well as an increase in the phosphorylation levels of downstream targets of Akt/mTORC1 signaling, including S6K and PRAS40. Finally, pretreatment with rapamycin dramatically inhibited the proliferation and migration of the LRCs induced by TPA in both nontransgenic and BK5.AktWT mice, supporting the hypothesis that mTORC1 activation is an important pathway responsible for the behavior of keratinocyte stem cells (KSCs) during the early stages of skin tumor development in this model system. Collectively, the data in the present study provide further support for the hypothesis that activation of mTORC1 and the subsequent activation of its downstream signaling pathways contribute significantly to tumor promotion in mouse skin.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

TPA, PD98059, and LY294002 were obtained from Alexis (San Diego, CA). Rapamycin and anti-K15 were purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA) and Covance (Princeton, NJ), respectively. PD153035, Akt VIII, and bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). 7,12-dimethylbenz (a) anthracene (DMBA), bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), anti-β-tubulin, anti-actin, EGF, and inhibitor cocktails of proteinase and phosphatases were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The following were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA): phospho-specific antibodies against MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204), RSK (Thr358/S363), Akt (Ser473, Thr308), FoxO3a (Thr32)/FoxO1 (Thr24), PRAS40 (Thr246), S6K (Thr389), S6 (Ser235/236, Ser240/244), eIF4G (Ser1108), panPKC (Ser660), eIF4E (Ser209), eIF4B (Ser422), 4EBP1 (Thr37/46, Ser65), TSC2 (Ser939, Thr1462), mTOR (Ser2448), and anti-Akt and mTOR antibodies. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and chemiluminescence detection kits were purchased from GE Healthcare Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ) and Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL), respectively.

Cell Culture

Keratinocytes were isolated from female ICR mice, 6–8 wks of age, and cultured in MEM-2 medium containing 1% FBS and a Ca2+ concentration of 0.04 mM as previously described [21].

Animals and Treatments

The dorsal skin of female FVB/N mice in the resting stage of the hair cycle (7–9 wks of age) was shaved 48 h prior to all treatments. Groups of 3–5 animals were used for each experiment. For biochemical experiments, mice received multiple (4) topical applications of TPA (6.8 nmol/0.2 mL) or acetone (0.2 mL) with or without rapamycin and were sacrificed at 6 h after treatment. For the evaluation of epidermal hyperplasia and labeling index (LI), dorsal skin was treated with various rapamycin doses (1000, 200, 50, 20, or 5 nmol) in 0.2 mL of acetone where indicated, 30 min prior to treatment with TPA (6.8 nmol). Mice (n > 4) treated with rapamycin and TPA were sacrificed 48 h later. BrdU (100 μg/gm body weight) was given by intraperitoneal injection 30 min prior to sacrifice.

Tumor Experiments

The dorsal skin of groups of 15 male and female mice 7–9 weeks of age was shaved and after 48 h was initiated by topical application of either 25 nmol of DMBA in 0.2 mL acetone or acetone. Two weeks after initiation, mice were treated topically twice weekly with various rapamycin doses or acetone, followed 30 min later by promotion with 6.8 nmol TPA for 20 weeks. Tumor multiplicity (average tumors/mouse), tumor incidence (percent mice with tumors), and body weight were recorded weekly for the remainder of the study.

Immunofluorescence Analyses

The expression and localization of K15, phospho-Akt, phospho-S6K, and phospho-PRAS40 were analyzed using immunofluorescence on skin sections as described [22].

Preparation of Epidermal Lysates and Western Blot Analysis

Preparation of epidermal whole cell lysates and western analyses were performed as previously described [15].

LRC Analysis

Ten-day-old pups received intraperitoneal injections of BrdU (50 μg/gm body weight) every 12 h for 2 d. After 70 d, dorsal skins were harvested, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and analyzed by immunohistochemistry for BrdU staining. BrdU positive cells were counted in a randomized blind experiment with at least three skin sections per animal and 3–6 animals per group were used for the quantitative analysis. For rapamycin and/or TPA treatment, BrdU injected mice were treated topically twice weekly for 2 wk with rapamycin (200 nmol) or acetone 30 min prior to 6.8 nmol TPA. Dorsal skins were analyzed for BrdU staining after 48 h following last treatment.

Statistical Analysis

For comparisons of LRC, epidermal thickness (μm) and LI (% BrdU positive cells), data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test with significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

TPA Activates mTORC1 Signaling in a Time-Dependent Manner in Cultured Primary Mouse Keratinocytes and the Immortalized Mouse Keratinocyte Cell Line, 3PC

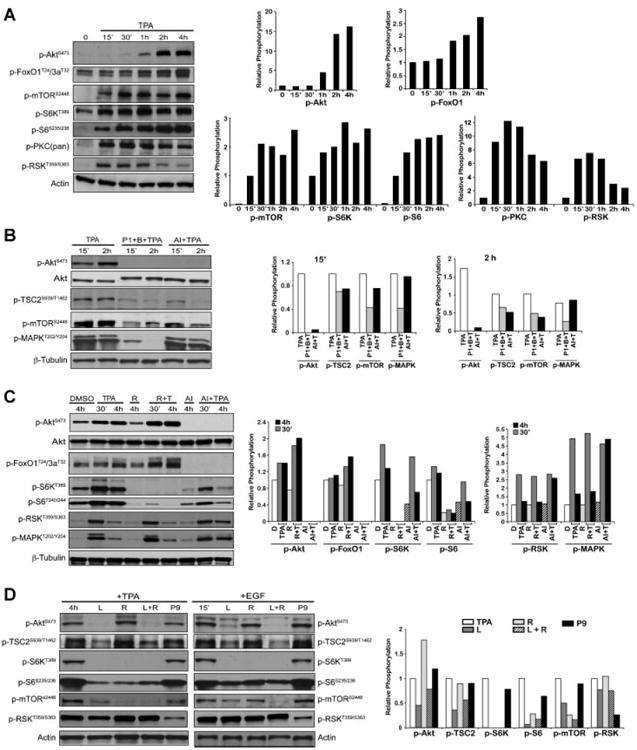

In previous studies, we demonstrated that diverse skin tumor promoters activated epidermal Akt in vivo, and that activation of Akt through activation of the EGFR following tumor promoter treatment leads to enhanced downstream signaling, including activation of the mTORC1 pathway [19,20]. In cultured mouse primary keratinocytes, TPA treatment also leads to activation of Akt with maximal phosphorylation at 2–4 h following treatment (Figure 1A and [19]). To further investigate activation of mTORC1 signaling by TPA, mouse primary keratinocytes were exposed to TPA (0.68 nmol/mL) in DMSO or EGF (40 ng/mL) following starvation and then cells were harvested at different time points. As shown in Figure 1A, mTOR phosphorylation and signaling downstream of mTORC1, was also increased rapidly after TPA treatment. Interestingly, following treatment of cultured mouse primary keratinocytes with TPA, mTORC1 signaling was activated in a time-dependent manner with an early initial peak at approximately 30 min and a later peak at approximately 4 h, as shown by phosphorylation of mTOR at S2448 and S6K at T389. The early activation of mTORC1 (15–30 min) appeared to be independent of Akt activation while the later activation appeared to be associated with Akt activation. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that increased phosphorylation of forkhead transcription factors (FoxO1/3a; downstream targets of Akt) was not evident until Akt was maximally activated. Further analyses revealed that TPA exposure led to rapid activation of PKC and the MAPK downstream effector, RSK, as is also shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

mTORC1 signaling in primary keratinocytes and 3PC cells in response to TPA. (A) Western analysis and quantification of the time course of mTORC1 signaling activation. Adult mouse primary keratinocytes were serum starved for 24 h and treated with TPA (0.68 nmol/mL). Cells were harvested and protein lysates prepared at the indicated time points. Western blot analysis was done using antibodies specific for phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-FoxO1 (Thr24)/3a (Thr32), phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), phospho-S6K(Thr389), phosphoribosomal S6 protein (Ser235/236), phospho-pan PKC(Ser660), and phospho-RSK (Thr359/Ser363). Actin was used to normalize protein loading. (B) Western analysis and quantification of the effect of Akt inhibition to mTORC1 activation. After starvation for 24 h, cultured keratinocytes were pretreated with EGFR inhibitor (P1, 100 nM PD153035) and PKC inhibitor (B, 1 μM bisindoylmaleimide I), or Akt inhibitor (AI, 5 μM Akt VIII) for 1 h prior to treatment with TPA. Keratinocytes were harvested at either 15 min or 2 h after treatment with TPA for the preparation of whole cell lysates. Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies for phospho- Akt (Ser473), Akt, phospho-TSC2 (Ser939/Thr1462), phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), phosphoMAPK (Thr202/Tyr204), and β-tubulin. Densitometric graphs were shown at 15 min and 2 h. β-Tubulin was used to normalize protein loading. (C) Western analysis and quantification of the effect of specific kinase inhibitors and the subsequent effect on mTORC1 downstream signaling following treatment with TPA in 3PC cells. After starvation for 18–24 h, 3PC cells were pretreated with the indicated inhibitors of R (100 nM rapamycin) or AI (5 μM Akt VIII) for 1 h prior to TPA exposure. 3PC cells were harvested at either 30 min or 4 h after treatment with TPA for the preparation of whole cell lysates. Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies for phospho-Akt (Ser473), Akt, phospho-FoxO1 (Thr24)/3a (Thr32), phospho-S6K(Thr389), phospho-ribosomal S6 protein (Ser240/244), phospho-RSK (Thr359/Ser363), phospho-MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204), and β-tubulin. β-Tubulin was used to normalize protein loading. Graphs represent the relative phosphorylation of the DMSO Western blots shown following normalization to the corresponding β-tubulin. (D) Inhibition of specific kinase pathways and the subsequent effect on mTORC1 downstream signaling following treatment with TPA or stimulation with EGF in primary keratinocytes. Cultured cells were starved for 24 h and treated with either L(50 μM LY294002), R (100 nM rapamycin), P9 (50 μM PD98059) or L ± R for 1 h prior to the addition of TPA (0.68 nmol/mL) for 4 h or EGF (40 ng/mL) for 15 min. Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates was done with antibodies specific for phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), phospho-TSC2 (Ser939), phospho-S6K (Thr389), phospho-ribosomal S6 protein (Ser235/236), phospho-RSK (Thr359/Ser363). Actin was used to normalize protein loading. Graphs represent the relative phosphorylation of the TPA Western blots shown following normalization to the corresponding actin.

Pretreatment with an inhibitor of Akt (AI) did not significantly affect the early phosphorylation of mTOR or TSC2, but significantly inhibited phosphorylation of both mTOR and TSC2 at the later time point (2 h; Figure 1B). When primary keratinocytes were treated with bisindolylmaleimide (B), a pan-inhibitor of PKC, prior to TPA treatment, the early phosphorylation of mTOR was decreased (data not shown) and a combination of inhibitors to simultaneously block both PKC (B) and the EGFR (PD153035; P1) led to inhibition of both the early and late phases of TPA-induced mTORC1 activation (Figure 1B). Previously, Roux and colleagues demonstrated that TPA inactivates TSC2 by phosphorylation via RSK, which results in mTORC1 activation at 15 min following TPA treatment in HEK293 cells [23]. Thus, the data presented in Figure 1A and B are consistent with this mechanism for the early activation of mTORC1 in mouse keratinocytes.

As part of the current study, we also investigated mTORC1-associated signaling after treatment with TPA in mouse 3PC cells. The nontumorigenic 3PC cell line was derived from adult SENCAR mouse keratinocytes exposed in vitro to DMBA [24]. In 3PC cells, TPA treatment induced rapamycin(R)-sensitive mTORC1 signaling indicated by phosphorylation of S6K and ribosomal S6 protein (Figure 1C) at both early (30 min) and later (4 h) time points. TPA also rapidly induced MAPK/RSK phosphorylation at 30 min. Pretreatment of 3PC cells with an Akt inhibitor (AI; 5 μM) resulted in significant inhibition of the later activation, but not the early activation of mTORC1 signaling stimulated by TPA (Figure 1C). Phosphorylation of downstream targets of Akt, FoxO1 and FoxO3a, was also inhibited (Figure 1C). Collectively, the data in both primary keratinocytes and 3PC cells indicate that the early phosphorylation of TSC2 and activation of mTORC1 signaling induced by TPA is mediated by PKC activation, whereas the later activation of mTORC1 is mediated by activation of EGFR and subsequent activation of PI3K/Akt signaling.

Effects of EGFR Downstream Kinase Inhibitors on TPA-Induced mTORC1 Activation in Cultured Primary Mouse Keratinocytes and 3PC Cells

To further analyze the role of specific EGFR downstream signaling pathways leading to the later phase (2–4 h) activation of mTORC1 signaling by TPA in cultured keratinocytes, various downstream inhibitors were used. Primary keratinocytes were treated with a PI3K inhibitor (LY294002, L), an mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin, R), a combination of both, or a MEK inhibitor (PD98059, P9) prior to treatment with TPA (Figure 1D). LY294002 (L) blocked both activation of Akt and mTORC1 signaling at 4 h following TPA treatment and 15 min after EGF treatment (Figure 1D). UCN01, a PDK1 inhibitor also reduced both TPA and EGF-induced Akt and mTORC1 activation at these same time points (data not shown). In contrast, PD98059 (P9) had little effect on Akt activation and signaling downstream of mTORC1 induced by treatment with either TPA or EGF at these time points (Figure 1D). Similar results were again obtained in 3PC cells (data not shown).

As shown in Figure 1C and D, rapamycin-treated keratinocytes exhibited increased Akt phosphorylation. These data are consistent with the previous observation that under certain conditions inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin in cultured cells leads to increased activation of Akt by a reduction in S6K-dependent negative feed back inhibition on signals upstream of Akt [25,26].

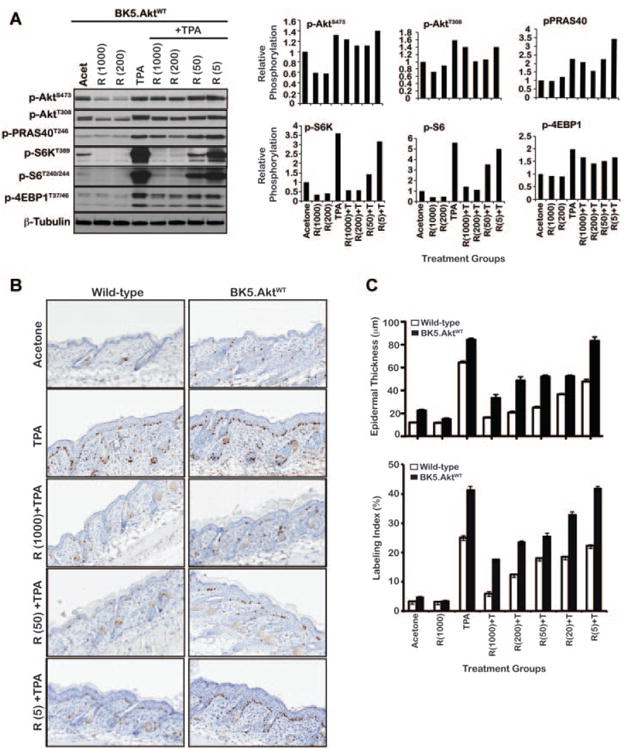

Elevated mTORC1 Signaling Contributes to Epidermal Hyperproliferation Following TPA Treatment in Epidermis of BK5.AktWT Transgenic Mice

BK5.AktWT transgenic mice, where Akt1 is overexpressed in basal epidermis, were previously shown to be significantly more sensitive to two-stage skin carcinogenesis compared to wild-type mice, developing papillomas with a much shorter latency, of considerably larger size, and with enhanced progression to SCCs [20]. As shown in Figure 2A, 6 h following multiple topical TPA treatments, Akt phosphorylation was elevated at both Ser473 and Thr308. At this time point, increased phosphorylation of a downstream target of Akt, PRAS40 was also observed along with increased mTORC1 signaling. In contrast, MAPK phosphorylation was not altered at this time point (data not shown), indicating that activation of mTORC1 signaling at 6 h after TPA treatment in mouse epidermis was primarily dependent on signaling via an Akt-dependent pathway. This Akt-dependent mTORC1 activation in epidermis of BK5.AktWT mice at 6 h after TPA treatment is consistent with the later activation seen in both cultured primary keratinocytes and 3PC cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of mTORC1 inhibition on epidermal hyperproliferation induced by TPA in BK5.AktWTmice. (A) Western analysis of epidermal lysates of BK5.AktWTmice after multiple TPA and/or rapamycin treament. For these experiments, mice (n = 5) received multiple (two times a week for 2 wk) topical applications of TPA (6.8 nmol) only or rapamycin 30 min prior to treatment with TPA. Control groups received acetone or rapamycin alone. Western blot analysis of epidermal protein lysates prepared from groups of mice sacrificed 6 h after treatment using antibodies specific for phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-Akt (Thr308), phospho-PRAS40 (Thr246), phospho-S6K (Thr389), phospho-ribosomal S6 (Ser240/244), and phospho-4EBP1 (Thr37/46). β-Tubulin was used to normalize protein loading. Graphs represent phosphorylation relative to the acetone control group following normalization to the corresponding β-tubulin. (B) Representative skin sections stained with BrdU after treatment for both BK5.AktWTand wild-type FVB/N mice. Mice (n = 3–4) were sacrificed 48 h after treatment. (C) Quantitative analysis of the effects of various concentrations of rapamycin on epidermal proliferation measured by epidermal thickness and labeling index (LI). Percent of BrdU incorporation was calculated as the number of BrdU-positive cells in the basal layer of the epidermis relative to the total number of cells. The reduction in both epidermal thickness and labeling index (LI) caused by pretreatment with rapamycin prior to TPA treatment was statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all doses examined in wild-type and for all doses examined except the 5 nmol dose in BK5.AktWT mice. Columns, mean; bars, SE.BK5.AktWT (black column), wild-type FVB/N mice (white column).

To further explore the role of mTORC1 signaling in the epidermal hyperproliferation induced following TPA treatment, we examined the impact of rapamycinon mTORC1 signaling in relation to its effect on TPA-induced epidermal cell proliferation in both wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice. Rapamycin, given topically at doses of 5–1000 nmol 30 min prior to 6.8 nmol TPA treatment (twice-weekly for 2 wk) inhibited epidermal mTORC1 signaling in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A). In addition, the effect of rapamycin treatment on TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation was also examined in both wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice. As shown in Figure 2B and C, BK5.AktWT mice were hypersensitive to TPA-induced epidermal proliferation and rapamycin significantly blocked this TPA-induced hyperplasia and hyperproliferation in a dose dependent manner. However, rapamycin was less effective compared to similar doses used in wild-type. The reduction in both epidermal thickness and LI caused by pretreatment with rapamycin prior to TPA treatment was statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all doses examined in wild-type and for all doses examined except the 5 nmol dose in BK5.AktWT mice. Collectively, these data indicate that signaling through mTORC1 contributes significantly to the enhanced epidermal hyperproliferation seen in BK5.AktWT mice following treatment with TPA and that these mice were still responsive to rapamycin treatment.

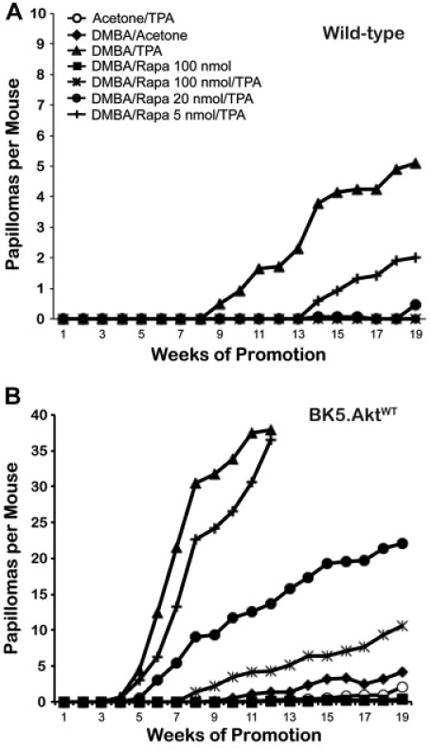

Targeting mTORC1 Effectively Inhibits Tumor Promotionin Epidermis of BK5.AktWT Mice

The effect of mTORC1 inhibition on TPA skin tumor promotion in BK5.AktWT mice was examined as shown in Figure 3. Groups of 15 male and female wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice were initiated with 25 nmol of DMBA or acetone. Two weeks after initiation, mice were treated topically twice a week with the indicated doses of rapamycin or acetone, followed by 6.8 nmol TPA. Tumor multiplicity and tumor incidence were tabulated weekly. Rapamycin effectively inhibited TPA skin tumor promotion in BK5.AktWT mice (Figure 3B) although higher doses were required to achieve similar levels of inhibition compared to wild-type mice (Figure 3A). In this regard, approximately 20 nmol per mouse was required in BK5.AktWT mice to produce ∼50% inhibition of papilloma formation (Figure 3B) compared to 5 nmol rapamycin in wild-type mice (Figure 3A). The effect of rapamycin was seen on both tumor incidence (data not shown) and tumor multiplicity and was clearly dose-dependent in both genetic backgrounds. These data demonstrate that rapamycin, although less potent, still retained significant inhibitory activity toward TPA promotion in BK5.AktWT mice, where Akt activity was constitutively elevated. Note that the DMBA-TPA control and the group receiving 5 nmol rapamycin were terminated early (12 weeks) due to high tumor burdens.

Figure 3.

Effect of mTORC1 Inhibition by rapamycin on skin tumor promotion in epidermis of BK5.AktWT mice. Tumor multiplicity (average papillomas per mouse) for wild-type FVB/N mice (A) and BK5.AktWT mice (B). Groups of 15 male and female mice 7–9 weeks of age were initiated with 25 nmol of DMBA. Two weeks after initiation, mice were treated topically twice weekly with indicated various rapamycin doses or acetone, followed by promotion with 6.8 nmol TPA for 20 wk. Acetone/TPA (○), DMBA/Acetone (◆), DMBA/TPA (σ), DMBA/100 nmol Rapamycin (ν), DMBA/100 nmol Rapamycin/TPA (T), DMBA/20 nmol Rapamycin/TPA (λ), DMBA/5 nmol Rapamycin/TPA (ψ). Differences in tumor multiplicity at 12 wk for the BK5.AktWT groups treated with 100 and 20 nmol rapamycin and the corresponding 6.8 nmol TPA treated group were statistically significant (P < 0.0001; P = 0.0007, respectively; Mann–Whitney U-test).

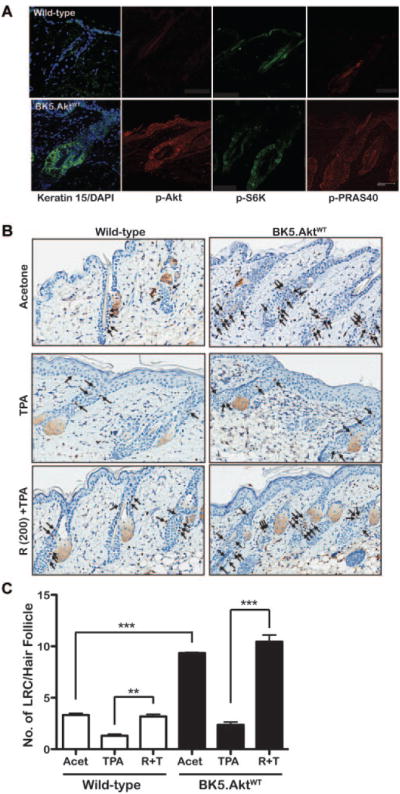

Elevated Akt Expression Leads to Expansion of KSCs in Hair Follicles of BK5.AktWT Mice

Although the overall role of Akt signaling in stem cells remains to be elucidated, this pathway has been implicated recently in regulation of self-renewal and differentiation in several stem cell populations [27– 31]. We previously reported that expression of constitutively active Akt in BK5.Aktmyr mice alters KSC homeostasis [32]. In the present study, we performed experiments using BK5.AktWT mice to further evaluate the status of bulge KSCs in hair follicles [reviewed in [33]] following TPA treatment and to examine the effect of mTORC1 inhibition. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that CD34 was expressed in the bulge region of hair follicles of both BK5.AktWT and wild-type mice (Supplemental Figure S1). This staining revealed an expanded population of cells expressing CD34 in the hair follicle of BK5.AktWT mice. As shown in Figure 4A, there was a significant expansion of the K15 expressing cell population in the hair follicle that coincided with expression of phospho-Akt (Ser473). A significant increase in phospho-S6K (Thr389) and phospho-PRAS40 (Thr246) especially in the hair follicles was also observed. These data suggested that elevated Akt activity in the K5 compartment of mouse epidermis (which includes bulge region KSCs) results in an expansion of the KSC population based on K15 and/or CD34 staining. The elevated staining for phospho-S6K and phospho-PRAS40 in hair follicles indicate a possible role for mTORC1 signaling in some of the alterations seen in the hair follicle bulge region.

Figure 4.

Effect of mTORC1 inhibition by Rapamycin on TPA-induced Proliferation of LRCs. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis of skin from wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice. Skin from wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice was stained using antibodies against Keratin 15/DAPI (merged), phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-S6K (Thr389), and phospho-PRAS40 (Thr246). Images were analyzed using a Leica Confocal microscope TCS SP5 X. White bar, 50 μm. (B) Representative skin sections stained with BrdU after treatment for the analysis of LRCs in the hair follicles of both BK5.AktWT and wild-type FVB/N mice. Ten-day-old mice received IP injections of BrdU (50 μg/gm of body weight) twice daily for 2 d. Dorsal skins of 13-wk-old mice were collected and stained for BrdU. The BrdU positive cells were counted and calculated as the number of BrdU-positive cells per hair follicle. For experiments examining the impact of TPA and/or rapamycin on LRCs, groups of mice injected with BrdU starting at 10 d of age as described above were treated after 11 wk with rapamycin (200 nmol) or acetone followed 30 min later by 6.8 nmol TPA twice a week for 2 wk. Forty-eight hours after the last TPA treatment, dorsal skins were again removed and processed for BrdU staining. The BrdU positive cells were counted in at least three skin sections per animal and 3–6 animals per group were used for the quantitative analysis. (C) Quantitative analysis of the effects of rapamycin (200 nmol) on LRCs activated by TPA. Numbers of BrdU positive LRCs in hair follicles were counted as described above. There were statistically significant differences in the average numbers of LRCs between wild-type FVB/N and BK5.AktWT mice (* * *, P < 0.01) and between TPA- and rapamycin/TPA-treated mice (* *, P < 0.05;, * * P < 0.001, respectively; Mann–Whitney U-test). Columns, mean; bars, SE. wild-type FVB/N mice (white column), BK5.AktWT (black column).

As part of this study, we also examined the number of LRCs in the hair follicles of BK5.AktWT mice. For these experiments, 10-day-old mice received intraperitoneal injections of BrdU (50 μg/gm body weight) twice a day for 2 d. Seventy days later, dorsal skins of the 13-wk-old mice were collected and BrdU staining of the skin sections was performed. As shown in Figure 4B and C, BK5.AktWT mice exhibited an increased number of LRCs (∼threefold) per hair follicle compared to wild-type mice (P < 0.0001).

mTORC1 Inhibition by Rapamycin Blocks TPA-Induced Proliferation of LRCs

To further examine the impact of mTORC1 signaling on KSCs during tumor promotion, groups of mice were injected with BrdU starting at 10 d of age as described above. Eleven weeks later mice were treated topically twice a week for 2 wk with rapamycin (200 nmol) or acetone followed 30 min later by 6.8 nmol TPA. Forty-eight hours after the last treatment, dorsal skins were removed and processed for BrdU staining. Following TPA treatment, most of the LRCs in the hair follicles were no longer present and only a few labeled cells were in the hair follicles and epidermis in both wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice (Figure 4B). These data indicate that LRCs underwent prompt proliferation and upward migration to the epidermis in response to tumor promoter treatment. In contrast, treatment with 200 nmol rapamycin prior to TPA dramatically inhibited proliferation and upward migration of LRCs to the epidermis. In this case, most LRCs remained in the hair follicles in or near the bulge region (Figure 4B). Quantitation of the hair follicle LRCs in this experiment is shown in Figure 4C. As shown, treatment with rapamycin significantly inhibited the exit of LRCs from the hair follicles. Collectively, these data suggest that signaling through mTORC1 contributes significantly to the proliferation and upward migration of KSCs during tumor promotion.

Discussion

In this study, we further examined the role of mTORC1 signaling during epithelial carcinogenesis and especially during tumor promotion using the mouse skin model of multistage carcinogenesis. Treatment of mouse primary keratinocytes and a nontumorigenic keratinocyte cell line (3PC) with TPA led to activation of mTORC1 in a time-dependent and pathway specific manner. Initially mTORC1 was activated early (15–30 min) following TPA treatment and then a later activation was observed at approximately 2–4 h (Figure 1). The early activation of mTORC1 was dependent on MAPK signaling through RSK while the later activation was dependent on Akt signaling via the EGFR. Rapamycin treatment completely abrogated increased mTORC1 signaling (both early and later time points) in response to TPA treatment in cultured primary keratinocytes and 3PC cells. The results using primary keratinocytes and the 3PC cell line were similar to data in vivo showing that activation of mTORC1 signaling at 6 h after TPA was primarily dependent on activation of Akt. A series of experiments were also conducted using a mouse model of elevated epidermal Akt activity, BK5.AktWT mice. These mice were previously shown to be hypersensitive to the tumor promoting actions of TPA [20]. mTORC1 downstream signaling was significantly elevated in epidermis of BK5.AktWT mice following topical treatment with TPA [20]. Topically applied rapamycin blocked TPA-induced mTORC1 signaling and epidermal hyperproliferation in both wild-type as well as BK5.AktWT mice (Figure 2 and [15]). In addition, rapamycin effectively blocked the promotion of skin tumors in BK5.AktWT mice although this required higher doses to achieve inhibition comparable to that in wild-type mice (Figure 3). Finally, evidence was obtained suggesting that elevated mTORC1 signaling was required for the proliferation and migration of keratinocyte stem/progenitor cells in the hair follicle and that blocking mTORC1 in both wild-type as well as BK5.AktWT mice inhibited the proliferation/migration of these cells during tumor promotion (Figure 4). Overall the data support the hypothesis that mTORC1 signaling plays an important role during skin tumor promotion through effects on keratinocyte proliferation, including keratinocyte stem/progenitor populations that are the targets for tumor development in this mouse model of epithelial carcinogenesis.

Previous work from our laboratory has shown that diverse tumor promoters such as TPA, okadaic acid, or chrysarobin lead to activation of both the EGFR and erbB2 in mouse epidermis [19,34–38]. Furthermore, activation of epidermal Akt during tumor promotion involves signaling primarily through the EGFR [19]. TPA, the most studied skin tumor promoter, initially activates epidermal PKC isozymes, especially those of the conventional and novel classes [39,40]. The activation of mTORC1 in cultured keratinocytes (both primary cultures and the 3PC cell line) exposed to TPA followed a temporal pattern involving early activation via a PKC-MAPK-RSK pathway and a later activation primarily via an EGFR-PI3K-Akt pathway. A similar early activation of mTORC1 via a PKC-MAPKRSK pathway was previously shown in HEK293 cells exposed to TPA [23]. During tumor promotion in vivo, repeated exposure to TPA leads to downregulation of many PKC isozymes [41,42], implying that other pathway(s) may be just as important or even more critical for the maintenance of epidermal proliferation during tumor promotion. Activation of both the EGFR and erbB2 (and downstream signaling) is sustained during tumor promotion in mouse epidermis and it is likely that activation of these receptors contribute significantly to the long-term activation of Akt and mTORC1 during tumor promotion in vivo.

In the current study, we used a novel mouse model of elevated Akt signaling (BK5.AktWT mice) to further analyze the role of mTORC1 signaling in skin tumor promotion. Previous studies with this transgenic mouse showed that mTORC1 signaling was elevated in the epidermis in the absence of any treatment [20] and that topical TPA treatment led to a greater increase in mTORC1 signaling compared to wild-type (Figure 2A and [20]). Rapamycin effectively inhibited mTORC1 signaling after topical application in both untreated and TPA treated mice. Furthermore, rapamycin blocked both TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and skin tumor promotion. Recently, we reported that rapamycin was a potent inhibitor of TPA skin tumor promotion in FVB/N mice [15]. Furthermore, rapamycin treatment caused a rapid decrease in phosphorylation of mTORC1 targets and inhibited TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and skin inflammation [15]. In the current study, topical treatment of rapamycin, given 30 min prior to TPA inhibited mTORC1 signaling as assessed by analysis of several downstream effectors in epidermal lysates from both wild-type and transgenic mice including S6K, S6, and 4EBP1. Moreover, TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation as well as tumor promotion were significantly blocked by rapamycin in a dose-dependent manner in both wild-type and BK5.AktWT (Figures 2 and 3). Thus, rapamycin was effective at blocking tumor promotion even in a setting where Akt/mTORC1 signaling was elevated, although higher doses were required to produce comparable inhibition in BK5.AktWT mice compared to wild-type. These results indicate that signaling through mTORC1 plays an important role in the heightened sensitivity of BK5.AktWT mice to skin tumor promotion by TPA.

Evidence has accumulated that hair follicle stem cells and their direct progenitors are the cells from which tumors arise [43–45]. Akt signaling has been implicated in regulation of various stem cell populations including neural stem cells, embryonic germ cells and epidermal progenitor cells. In neural stem cells, Notch regulated stem cell survival appears to be mediated by Akt and mTOR [27]. Cell population sizes in both embryonic germ cells and neural stem cells are increased in tissue specific PTEN-deficient mice, in which Akt activity is upregulated [28,29]. Similar effects on cell populations were observed in progenitor cell populations found in transgenic mice when Akt was conditionally activated [30]. Analyses of Akt knockout (KO) mice further suggest a role for Akt in stem cell regulation. In this regard, double KO mice of Akt isoforms 1/2 and 1/3 exhibit marked decreases in the number of hair follicles, as well as a hypoplastic epidermis [46]. Additional evidence suggests a role for activated Akt in the maintenance of pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells [31]. Previously, we reported that elevated Akt activity altered KSC homeostasis [32] in another Akt transgenic mouse line (L84) that expresses a constitutively active Akt (Aktmyr) under control of the K5 promoter. These transgenic mice were characterized by an increase in hair follicle cells expressing two putative epidermal stem cell markers, K15 and CD34 [47] and a consistent increase in the number of LRCs [48] 30 d after BrdU administration compared with wild-type. Furthermore, adult epidermal cells from L84 displayed an undifferentiated morphology and produced multiple colonies in colony-forming efficiency assays compared to cells from wild-type. These data suggested that expression of constitutively active Akt resulted in an expansion of the epidermal stem/progenitor cell population. Moreover, similar results related to expansion of the stem cell compartment in oral epithelium of L84 mice were recently obtained [49].In our current study, we found expansion of the KSC population in untreated BK5.AktWT mice based on both CD34 and K15 staining (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure S1) and LRC analysis (Figure 4B and C). Furthermore, both phospho-PRAS40 and phospho-S6K were elevated especially in hair follicles of BK5. AktWT mice (Figure 4A) indicating constitutive activation of mTORC1 in stem/progenitor populations that could account for at least some of the alterations in CD34/K15 expressing cells. Thus, elevated mTORC1 signaling in keratinocyte stem/progenitor populations may have contributed to the observed expansion of this population of cells.

To determine if inhibiting mTORC1 might have potentially selective effects on the target cells for tumor development, studies were conducted to examine and trace the bulge LRCs in response to treatment with TPA both with and without rapamycin treatment. As shown in Figure 4B, following TPA treatment most LRCs exited the bulge region and moved upward toward the interfollicular epidermis. This was true in both wild-type as well as BK5.AktWT mice. Interestingly, rapamycin significantly inhibited the migration of LRCs toward the epidermis (Figure 4B and C). Consistent with our data, the recent paper by Castilho et al. [50] reported that rapamycin retained CD34+ cells in the hair follicle bulge region of K5rtTA/tet-Wnt1 mice. These findings suggest that mTORC1 signaling contributes to proliferation and migration of KSCs. The data also suggest the possibility of some selective effects of mTORC1 inhibition on these cells. Additional studies are underway to explore this possibility further.

In conclusion, the current results support the hypothesis that elevated mTORC1 activation and subsequent activation of downstream signaling are important events in mouse keratinocytes following treatment with skin tumor promoters. Furthermore, the data demonstrate the importance of both Akt and mTORC1 signaling pathways as potential targets for prevention strategies for epithelial cancers. Finally, the data suggest the possibility that targeting mTORC1, in particular, may provide some selectivity for inhibiting the proliferation of the target cells for tumor development in this model system.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Immunostaining with CD34 in skin from wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice. Skins from wild-type and BK5.AktWT were stained using the antibody against CD34 (BD Pharmigen).

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant numbers: CA037111, CA129409; Grant sponsor: NIEHS Center; Grant number: P30ES007784

Abbreviations

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- LRC

label retaining cell

- KSC

keratinocyte stem cells

- AktWT

wild-type Akt1

- BK5

bovine keratin 5

- DMBA

7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site.

References

- 1.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: Rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay N. The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruggero D, Sonenberg N. The Akt of translational control. Oncogene. 2005;24:7426–7434. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, et al. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1. Dev Cell. 2006;11:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petroulakis E, Mamane Y, Le Bacquer O, Shahbazian D, Sonenberg N. mTOR signaling: Implications for cancer and anticancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:195–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, et al. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell. 2006;127:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seeliger H, Guba M, Kleespies A, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. Role of mTOR in solid tumor systems: A therapeutical target against primary tumor growth, metastases, and angiogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:611–621. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janus A, Robak T, Smolewski P. The mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) kinase pathway: Its role in tumourigenesis and targeted antitumour therapy. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2005;10:479–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost P, Moatamed F, Hoang B, et al. In vivo antitumor effects of the mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 against human multiple myeloma cells in a xenograft model. Blood. 2004;104:4181–4187. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito D, Fujimoto K, Mori T, et al. In vivo antitumor effect of the mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 and gemcitabine in xenograft models of human pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2337–2343. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namba R, Young LJ, Abbey CK, et al. Rapamycin inhibits growth of premalignant and malignant mammary lesions in a mouse model of ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2613–2621. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Checkley LA, Rho O, Moore T, Hursting S, DiGiovanni J. Rapamycin is a potent inhibitor of skin tumor promotion by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1011–1020. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Gruijl FR, Koehl GE, Voskamp P, et al. Early and late effects of the immunosuppressants rapamycin and mycophenolate mofetil on UV carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:796–804. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raimondi AR, Molinolo A, Gutkind JS. Rapamycin prevents early onset of tumorigenesis in an oral-specific K-ras and p53 two-hit carcinogenesis model. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4159–4166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Perez P, et al. Functional roles of Akt signaling in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:53–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu J, Rho O, Wilker E, Beltran L, DiGiovanni J. Activation of epidermal Akt by diverse mouse skin tumor promotion. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;12:1342–1352. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segrelles C, Lu J, Hammann B, et al. Deregulated activity of Akt in epithelial basal cells induces spontaneous tumors and heightened sensitivity to skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10879–10888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiguchi K, Beltran L, Rupp T, DiGiovanni J. Altered expression of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands in tumor promoter-treated mouse epidermis and in primary mouse skin tumors induced by an initiation-promotion protocol. Mol Carcinog. 1998;22:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim DJ, Kataoka K, Rao D, Kiguchi K, Cotsarelis G, Digiovanni J. Targeted disruption of stat3 reveals a major role for follicular stem cells in skin tumor initiation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7587–7594. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roux PP, Ballif BA, Anjum R, Gygi SP, Blenis J. Tumor-promoting phorbol esters and activated Ras inactivate the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13489–13494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405659101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klann RC, Fitzgerald DJ, Piccoli C, Slaga TJ, Yamasaki H. Gap-junctional intercellular communication in epidermal cell lines from selected stages of SENCAR mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1989;49:699–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manning BD, Logsdon MN, Lipovsky AI, Abbott D, Kwiatkowski DJ, Cantley LC. Feedback inhibition of Akt signaling limits the growth of tumors lacking Tsc2. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1773–1778. doi: 10.1101/gad.1314605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang HH, Lipovsky AI, Dibble CC, Sahin M, Manning BD. S6K1 regulates GSK3 under conditions of mTOR-dependent feedback inhibition of Akt. Mol Cell. 2006;24:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Leker RR, Soldner F, et al. Notch signalling regulates stem cell numbers in vitro and in vivo. Nature. 2006;442:823–826. doi: 10.1038/nature04940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groszer M, Erickson R, Scripture-Adams DD, et al. Negative regulation of neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation by the Pten tumor suppressor gene in vivo. Science. 2001;294:2186–2189. doi: 10.1126/science.1065518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura T, Suzuki A, Fujita Y, et al. Conditional loss of PTEN leads to testicular teratoma and enhances embryonic germ cell production. Development. 2003;130:1691–1700. doi: 10.1242/dev.00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murayama K, Kimura T, Tarutani M, et al. Akt activation induces epidermal hyperplasia and proliferation of epidermal progenitors. Oncogene. 2007;26:4882–4888. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe S, Umehara H, Murayama K, Okabe M, Kimura T, Nakano T. Activation of Akt signaling is sufficient to maintain pluripotency in mouse and primate embryonic stem cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:2697–2707. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segrelles C, Moral M, Lorz C, et al. Constitutively active Akt induces ectodermal defects and impaired bone morphogenetic protein signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:137–149. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal stem cells of the skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:339–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xian W, Rosenberg MP, DiGiovanni J. Activation of erbB2 and c-src in phorbol ester-treated mouse epidermis: Possible role in mouse skin tumor promotion. Oncogene. 1997;14:1435–1444. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xian W, Kiguchi K, Imamoto A, Rupp T, Zilberstein A, DiGiovanni J. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by skin tumor promoters and in skin tumors from SENCAR mice. Cell Growth Diff. 1995;6:1447–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan KS, Carbajal S, Kiguchi K, Clifford J, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated activation of Stat3 during multistage skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2382–2389. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rho O, Beltran LM, Gimenez-Conti IB, DiGiovanni J. Altered expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-alpha during multistage skin carcinogenesis in SENCAR mice. Mol Carcinog. 1994;11:19–28. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rho O, Kim DJ, Kiguchi K, Digiovanni J. Growth factor signaling pathways as targets for prevention of epithelial carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:264–279. doi: 10.1002/mc.20665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arcoleo JP, Weinstein IB. Activation of protein kinase C by tumor promoting phorbol esters, teleocidin and aplysiatoxin in the absence of added calcium. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6:213–217. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kikkawa U, Kishimoto A, Nishizuka Y. The protein kinase C family: Heterogeneity and its implications. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:31–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young S, Parker PJ, Ullrich A, Stabel S. Down-regulation of protein kinase C is due to an increased rate of degradation. Biochem J. 1987;244:775–779. doi: 10.1042/bj2440775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Z, Liu D, Hornia A, Devonish W, Pagano M, Foster DA. Activation of protein kinase C triggers its ubiquitination and degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:839–845. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kangsamaksin T, Park HJ, Trempus CS, Morris RJ. A perspective on murine keratinocyte stem cells as targets of chemically induced skin cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:579–584. doi: 10.1002/mc.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S, Park H, Trempus CS, et al. A keratin 15 containing stem cell population from the hair follicle contributes to squamous papilloma development in the mouse. Mol Carcinog. 2012 doi: 10.1002/mc.21896. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White AC, Tran K, Khuu J, et al. Defining the origins of Ras/p53-mediated squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7425–7430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012670108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peng XD, Xu PZ, Chen ML, et al. Dwarfism, impaired skin development, skeletal muscle atrophy, delayed bone development, and impeded adipogenesis in mice lacking Akt1 and Akt2. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1352–1365. doi: 10.1101/gad.1089403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Lyle S, Yang Z, Cotsarelis G. Keratin 15 promoter targets putative epithelial stem cells in the hair follicle bulge. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:963–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor G, Lehrer MS, Jensen PJ, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Involvement of follicular stem cells in forming not only the follicle but also the epidermis. Cell. 2000;102:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moral M, Segrelles C, Lara MF, et al. Akt activation synergizes with Trp53 loss in oral epithelium to produce a novel mouse model for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1099–1108. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castilho RM, Squarize CH, Chodosh LA, Williams BO, Gutkind JS. mTOR mediates Wnt-induced epidermal stem cell exhaustion and aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Immunostaining with CD34 in skin from wild-type and BK5.AktWT mice. Skins from wild-type and BK5.AktWT were stained using the antibody against CD34 (BD Pharmigen).