Abstract

Chronic increases in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity in the heart are known to alter gene expression potentially modifying Ca2+-homeostasis and inducing arrhythmias. We tested age-dependent effects of a chronic increase in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity on induction of altered alter gene expression and activity of Ca2+ transport systems in cardiac myocytes. Our approach was to determine the relative contributions of the major mechanisms responsible for restoring Ca2+ to basal levels in field stimulated ventricular myocytes. Comparisons were made from ventricular myocytes isolated from non-transgenic (NTG) controls and transgenic mice expressing the fetal, slow skeletal troponin I (TG-ssTnI) in place of cardiac TnI (cTnI). Replacement of cTnI by ssTnI induces an increase in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity. Comparisons included myocytes from relatively young (5–7 months) and older mice (11–13 months). Employing application of caffeine in normal Tyrode and in 0Na+ 0Ca2+ solution, we were able to dissect the contribution of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump (SR Ca2+-ATPase), the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), and “slow mechanisms” representing the activity of the sarcolemmal Ca2+ pump and the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. The relative contribution of the SR Ca2+-ATPase to restoration of basal Ca2+levels in younger TG-ssTnI myocytes was lower than in NTG (81.12 ± 2.8% vs 92.70 ± 1.02%), but the same in the older myocytes. Younger and older NTG myocytes demonstrated similar contributions from the SR Ca2+-ATPase and NCX to restoration of basal Ca2+. However, the slow mechanisms for Ca2+ removal were increased in the older NTG (3.4 ± 0.3%) vs the younger NTG myocytes (1.4 ± 0.1%). Compared to NTG, younger TG-ssTnI myocytes demonstrated a significantly bigger contribution of the NCX (16 ± 2.7% in TG vs 6.9 ± 0.9% in NTG) and slow mechanisms (3.3 ± 0.4% in TG vs 1.4 ± 0.1% in NTG). In older TG-ssTnI myocytes the contributions were not significantly different from NTG (NCX: 4.9 ± 0.6% in TG vs 5.5±0.7% in NTG; slow mechanisms: 2.5 ± 0.3% in TG vs 3.4 ± 0.3% in NTG). Our data indicate that constitutive increases in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity alter the relative significance of the NCX transport system involved in Ca2+-homeostasis only in a younger group of mice. This modification may be of significance in early changes in altered gene expression and electrical stability hearts with increased myofilament Ca-sensitivity.

Keywords: troponin I, arrhythmia, Ca-sensitizer, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

INTRODUCTION

Apart from its critical role in triggering contraction of cardiac myofilaments by binding to troponin C (cTnC), Ca2+ regulates a variety of cellular processes involved in both long and short-term control of cardiac function. Ca2+ binding domains on Ca2+ channels and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger regulate Ca2+ entry into and exit from the cells. Ca2+-dependent kinases also regulate Ca2+ transport and myofilament response to Ca2+. Moreover, Ca2+-calmodulin dependent kinases and phosphatases also potentially regulate transcription, translation, and metabolism [1, 2]. Homeostasis of cardiac function requires a well-integrated interplay of Ca2+ fluxes controlling contraction, excitation contraction and energy coupling as well as gene expression [3]. A disruption in this Ca2+ homeostasis is a hallmark of cardiac failure [4].

As the major site of Ca2+-binding in the ventricular myocyte, it is important to understand to what extent alterations in Ca2+ buffering by the myofilaments influence Ca2+ fluxes and/or gene expression. The major physiological mechanisms by which alterations in cTnC Ca2+-binding appear to occur are by changes in sarcomere length and phosphorylation of troponin I (cTnI) by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). The effects of these alterations in cTnC Ca2+-affinity have been reported to include alterations in the amplitude and dynamics of the Ca2+transient and contraction [5]. For example, stretch of the cardiac myocytes and the associated increase in sarcomere length, which is likely to result in an increase in cTnC Ca2+-affinity [6] induces an immediate prolongation of contraction. Whether this change in Ca2+-affinity affects the Ca2+ transient is not clear, as some reports indicate no change [7], whereas others report an increase in its amplitude or a decrease in its duration. Alteration of cTnC Ca2+-affinitywith EMD 57033 results in a decrease in the Ca2+-transient amplitude and prolongation of its declining phase [8] with no change in the rise time. Variations in cardiac function as a consequence of ischemia, reperfusion injury and stunning also appear to involve major changes in myofilament response to Ca2+ [9, 10]. One might also expect that a reduction in myofilament Ca2+-affinity may contribute to elevations in diastolic Ca2+ and to induce arrhythmias.

Whether long-term changes in myofilament sensitivity to Ca2+ affect gene expression and Ca2+ fluxes in the heart remains an important question. Mutations in sarcomeric proteins linked to familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathies (FHC) very frequently induce an increase in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity [11, 12]. This constitutive change in Ca2+-sensitivity restricts the dynamic range over which sarcomeres respond to physiological regulators such as protein phosphorylation [13, 14] and sarcomere length [15]. It is apparent, for example in the case of mutations in tropomyosin [16] and troponin T (cTnT) [17], that the increase in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity may slow down relaxation and lead to diastolic abnormalities that trigger signaling of hypertrophy. Baudenbacher et al. [18] reported that increased cardiac myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity induced a susceptibility to arrhythmias and a risk of developing ventricular tachycardia proportional to the extent of Ca2+-sensitization induced by various myofilament modifications.

In the work presented here, we have investigated the effects of a prolonged constitutive increase in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity on cellular Ca2+ fluxes by employing the transgenic mouse model (TG-ssTnI) in which ssTnI completely replaces cardiac troponin I (cTnI). Unlike cTnI, ssTnI does not have sites for phosphorylation by PKA. Moreover, we have previously reported that compared to controls, TG-ssTnI cardiac myofilaments demonstrate a substantial increase in Ca2+-sensitivity [19], a resistance to desensitization by acidic pH [20], and a blunted response to changes in sarcomere length [21]. Hearts of TG-ssTnI mice are also significantly resistant to ATP loss in global ischemia associated with remodeling to a relatively high glycolytic phenotype compared to controls [22]. We studied isolated cardiac myocytes from relatively young mice (5~7 months old) and relatively old mice (11~13 months old). Our results demonstrate that increased myofilament sensitivity to Ca2+ is likely to be an important factor, which contributes to the increased expression and activity of the NCX in younger mice and a decreased expression of SERCA2a in older mice. While a direct correlation between increased Ca-sensitivity and expression of NCX and SERCA2a is not established by our findings, our data suggest that persistent increases in myofilament Ca-sensitivity alters the time course of age dependent changes in NCX and SERCA2a protein expression.

METHODS

Transgenic animals

Mice expressing ssTnI in the heart were generated as previously described [19]. The transgene was under the control of the cardiac specific alpha-myosin heavy chain promoter and there was complete and stoichiometric replacement of cTnI by ssTnI in myofilaments from the TG-ssTnI mice. To determine time dependent alterations, we studied a group of relatively young mice (5~7 months old) and a group of older mice (11~13 months old).

Isolation of myocytes

Adult mice were heparinized (5,000 U/kg body wt), and after 30 min anesthetized with ether. Left ventricular myocytes were isolated as previously described [23] and were studied 1–6 hrs after isolation.

Measurements of intracellular Ca2+transients and cell shortening

After isolation the cells were loaded for 20 min at room temperature with 10 μM Fluo3-AM followed by a 30 min washout. Cells were excited at 480 ± 5 nm using a 75 W Xenon arc lamp via epi-illumination, and emitted fluorescence at 535 ± 20 nm was recorded using photomultipliers (PTI Corporation). Background fluorescence was measured each day as the average fluorescence from 10 cells not loaded with Fluo3-AM of the same preparation. Fluorescence values are expressed as a pseudo ratio F/F0, where the emitted fluorescence F is divided by the resting emitted fluorescence F0. Cell shortening was recorded using a video edge detection system. Length changes were expressed as percentage of the resting length.

Solutions

The modified normal Tyrode (NT) solution had the following composition (mM): 140 NaCl, 6 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2 10 glucose and 5 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES). In the Na- and Ca-free solution, NaCl was replaced with LiCl, CaCl2 was omitted and 1mM ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′-N′ tetraacetic acid (EGTA). All solutions had pH 7.4 at room temperature.

Experimental Procedure

Cells were equilibrated for 15 min in NT and paced at 0.5 Hz by field stimulation using platinum electrodes. Once a steady-state contraction level was achieved, the control twitch contraction and Ca2+ transient were recorded. Electrical stimulation was then stopped before rapidly switching to NT solution containing 10 mM caffeine (CaffNT). Sustained exposure of cells to CaffNT induces release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and inhibition of SR Ca2+ re-uptake [24]. Thus, CaffNT produced a long lasting contracture. After complete relaxation of the contracture, superfusion with caffeine solution was stopped and myocytes were washed with NT for ~ 1 min before electrical stimulation was resumed. After a recovery period of 5 min, twitch contractions returned to steady-state level. Stimulation was again stopped and myocytes were bathed in Na+- and Ca2+ -free solution for 15 s before application of 10 mM caffeine in Na+- and Ca2+ -free solution (Caff00). Similarly to the previous application, caffeine in 0Na+ and 0Ca2+ induces a contracture in the cell (this time stronger due to the absence of NCX in the removal process). After recovery from the contracture, myocytes were washed with NT for 1 min before stimulation was resumed.

Evaluation of contribution to Ca2+ fluxes during relaxation

Data from the time course of relaxation of cell length and Ca2+ transients in NT, CaffNT and Caff00 were used to determine the relative contribution of the major Ca2+ transport mechanisms involved in cardiac relaxation. During a twitch the Ca2+ removal systems include the SR Ca2+ pump (SR Ca2+-ATPase), the Na/Ca exchange (NCX), and slow mechanisms (SLCa2+ pump and the mitochondria uniporter). However, in the presence of CaffNT, the primary means of Ca2+ extrusion from the cytoplasm is the NCX. During caffeine application in 0Na0Ca, the NCX is not able to work (and caffeine prevents SR Ca2+ uptake) leaving only the slow mechanisms working.

Calculation of the relative contribution of each system was carried out as described by Puglisi et al. [25], equating the relaxation time constant Tau (τ) of the Ca2+ transients to the various conditions as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Where KSR, KNCX and Kslow represent the rates from the SR, the NaCa Exchanger and the slow mechanisms respectively. From the value of 1/τCaff00, we inferred directly the rate of the slow mechanisms. Subtracting the rate of the slow mechanisms from 1/τCaffNT, we obtained the rate of NCX and finally subtracting the rate of the slow mechanisms and the rate of NCX from 1/τtwitch, we obtained the rate of the SR Ca2+-ATPase. From each of the rate values and the total we computed the relative participation of each system in Ca2+ removal during relaxation.

Effect of caffeine on cardiac myofilaments response to Ca2+

Hearts were quickly excised from NTG and TG-ssTnI mice (male and female) that had been deeply anesthetized by intra-peritoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body weight). After the hearts were placed in ice cold saline and washed free of blood, fiber bundles were dissected on a cold plate (4° C) from the left ventricular papillary muscle. These fiber bundles (approximately 150–200 μm in width and 3–4 mm in length) were extracted overnight at 4° C in a high relaxing (HR) solution 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 53.5 mM KCl, 10 mM EGTA, 0.025 mM CaCl2, 1 mM free Mg2+, 5 mM MgATP, 12 mM creatine phosphate, 10 IU/ml creatine kinase (bovine heart, Sigma), 1 mM DTT and 1% Triton X-100. A cocktail of protease inhibitors was included in all buffers (1 μg/ml pepstatin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin and 0.2 mM PMSF). The detergent extracted fiber bundles were mounted with fast setting glue in a previously described [26] apparatus for measurement of sarcomere length by laser diffraction and determination of isometric tension. Sarcomere length was set at 2.3 μm in HR. Maximum force was measured first in an activating solution at pCa 4.5 and containing 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 33.8 mM KCl, 10 mM EGTA, 9.96 mM CaCl2, 5.39 mM ATP, 6.47 mM MgCl2, 12 mM creatine phosphate, 10 IU/ml creatine kinase and 1 mM DTT. Tension was then measured in fiber bundles incubated in HR, followed by solutions containing values between pCa 8 to pCa 4.5, calculated as previously described (26).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Gene expression analysis was conducted by real-time quantitative RT-PCR with SYBR Green detection in the LightCycler thermocycler (Roche Diagnostics). Each one-step RT-PCR reaction employed 100 ng of total RNA, which had been extracted from the apex of the heart using TRIzol (Life Technologies) reagent. Quantification of the RT-PCR was carried out as described previously [27] by running a series of in vitro transcribed mRNA standards prepared for each gene alongside the unknowns. Melting curve analysis was performed on the standards prior to determine the specific temperature (the Tm of the PCR product) at which the fluorescent signal should be acquired, thereby excluding fluorescence from non-specific products and/or primer dimers, which can be detected with the SYBR Green dye. The reaction conditions for the reverse transcriptase were 55° C for 15 min, followed by 95° C for 30 sec. This was followed by a four-step PCR amplification to quantify the expression of the various genes. The steps were: 95° C for 1 sec, 55–60 ° for 1 sec (depending on primer Tm), 72° C for 10 sec with signal acquisition at 80–89° C for 2 sec (depending on Tm of amplicon) for 40 cycles. The second derivative maximum (log linear phase) for each amplification curve was determined and plotted against GAPDH expression to ensure equal loading. As a final step to ensure correct amplification, appropriate size determination was made for each amplicon by electrophoresis. Primers used were selected against regions close to the 3′ end of the gene of interest as previously published (27, 30).

Western Blot Analysis

We homogenized tissue samples in ice cold buffer containing (mM) imidazole 10; sucrose 300, DTT 1, Na metabisulfite 1, EDTA 2, pH 8.2, along with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Protein concentration was measured using the Lowry assay. Proteins (75–100 μg total) were loaded on to a 10% polyacrylamide gel and separated by electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose using a wet blot apparatus (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% non-fat milk-phosphate buffered saline, 0.1% Tween (1:1000 dilution; ABR). Blots were washed for 30 min in 0.05% PBS-T and subsequently incubated in anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector Labs). The blot was then rinsed with PBS-T and incubated in ABC mix (Vector Labs) for 1 h. Following another 30 min wash, a DAB substrate kit was used for protein detection [28]. We used the following antibodies: For NCX (R3F1 SWANT; Bellinzona (Switzerland)); for SERCA2a Thermo Scientific (Clone 2A7-A1), and the GAPDH (FL-335) antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology for normalization. For SERCA2a blots, we used a 12% SDS-PAGE criterion gel with 20 μg protein loaded with transfer to a 0.2um PVDF membrane.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SE. The Student’s t-test was used for paired observations. Statistical comparison of values between cells from TG-ssTnI and NTG was carried out using ANOVA followed by a post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The experiments were designed to compare the relative contribution to relaxation of the major Ca2+ transport mechanisms in the cell; namely the SR Ca2+-ATPase, responsible for the Ca2+ flux trough the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), the NCX responsible of the main flux through the cell membrane and the slower fluxes carried out by the sarcolemma Ca2+ pump and the mitochondria uniporter (referred to as slow mechanisms) in TG-ssTnI and non NTG cardiomyocytes. To determine age dependent effects on these Ca2+ fluxes, experiments were carried out on isolated myocytes from mice 5–7 months of age and mice from 11–13 months of age. Fluorescence and shortening traces from TG-ssTnI and NTG hearts were measured in normal Tyrode (NT), caffeine in normal Tyrode (CaffNT) and caffeine in Tyrode free of Na+ and Ca2+ (Caff00). In NT, Ca2+ removal during relaxation of mouse heart cells occurs by the action of the three mechanisms: the SR Ca2+-ATPase that resequesters Ca2+ back to the SR, the NCX working in the forward mode extruding Ca2+ of the cytoplasm, and the slow mechanisms also removing Ca2+ from the cytoplasm. During caffeine application in NT, SR uptake is suppressed leaving the activity of the NaCa exchange and the slow mechanisms as the means for Ca2+ extrusion. In Caff00 the activity of the NCX is also suppressed and the slow mechanisms are the only active Ca2+ removal systems.

Cardiomyocyte Studies

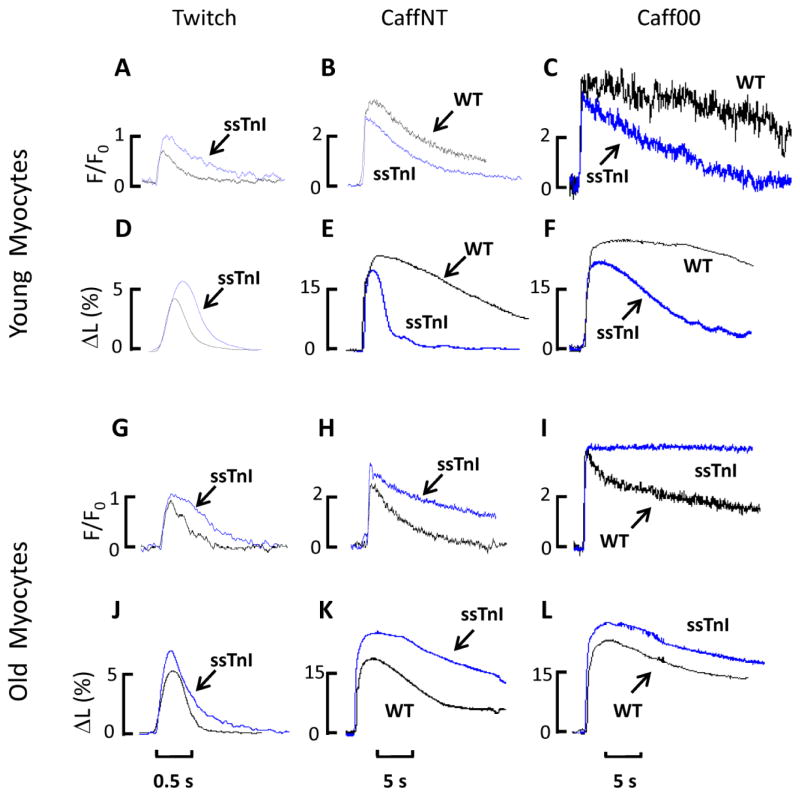

Figure 1 compares traces of fluorescence and shortening for myocytes from the younger (Fig. 1A–F) and older (Fig. 1G–L) groups of myocytes from TG-ssTnI and NTG mouse hearts. Although traces in Figure 1A indicate that peak amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was increased and decay kinetics were slower in TG-ssTnI myocytes, this difference did not turn out to be significant (Fig. 2). However, compared to NTG, the amplitude of shortening shown in Figure 1D was significantly increased in TG-ssTnI myocytes (Figs. 1D and 2). These mechanical differences reflect in part the increased sensitivity of the TG-ssTnI myofilaments to Ca2+, but may also reflect altered Ca2+ fluxes. Figure 1B shows changes in fluorescence in a cell during caffeine application in NT and Figure 1E the corresponding cell shortening record. As expected in CaffNT without a functional SR, Ca2+ signal relaxation was substantially prolonged for both TG-ssTnI and NTG myocytes. In both recordings of fluorescence (Fig. 1B) and shortening (Fig. 1E) the data indicate that Ca2+ removal from the cytoplasm by non-SR fluxes is enhanced in TG-ssTnI compared to NTG myocytes. As summarized in Figure 2 both the decay constant τ and decay half time (t1/2) were significantly abbreviated in TG-ssTnI versus NTG myocytes. Similar differences were recorded during Caff00 applications (Figs. 1C and 1F). These data indicate that fluxes, through the NCX and through the slow mechanisms are enhanced in the TG-ssTnI myocytes compared to the NTG from the younger group of mouse hearts.

Fig. 1. Superimposed Ca2+ transients and shortening traces obtained in TG-ssTnI and NTG young and older adult myocytes.

Fluorescence signals (expressed as F/F0) from Ca2+ transients of young myocytes recorded during a twitch (A), caffeine application in NT solution (B) and caffeine in Na- and Ca-free solution (C). Re-lengthening and shortening (expressed as a percentage of the total cell length) are depicted in the lower panel for twitch (D), contracture under caffeine in NT (E) and contracture under caffeine in Na- and Ca-free solution (F). Fluorescence signals (expressed as F/Fo) for older adult myocytes during a twitch (G), contractures induced by caffeine application in NT solution (H) and in Na- and Ca-free solution (I). Shortening traces (expressed as percentage of total cell length) for a twitch (J), CaffNT (K) and Caff00 (L). Note the larger amplitudes and longer duration in older TG-ssTnI myocytes twitch and contractures compare to older NTG, which are opposite the results obtained from the young group of myocytes.

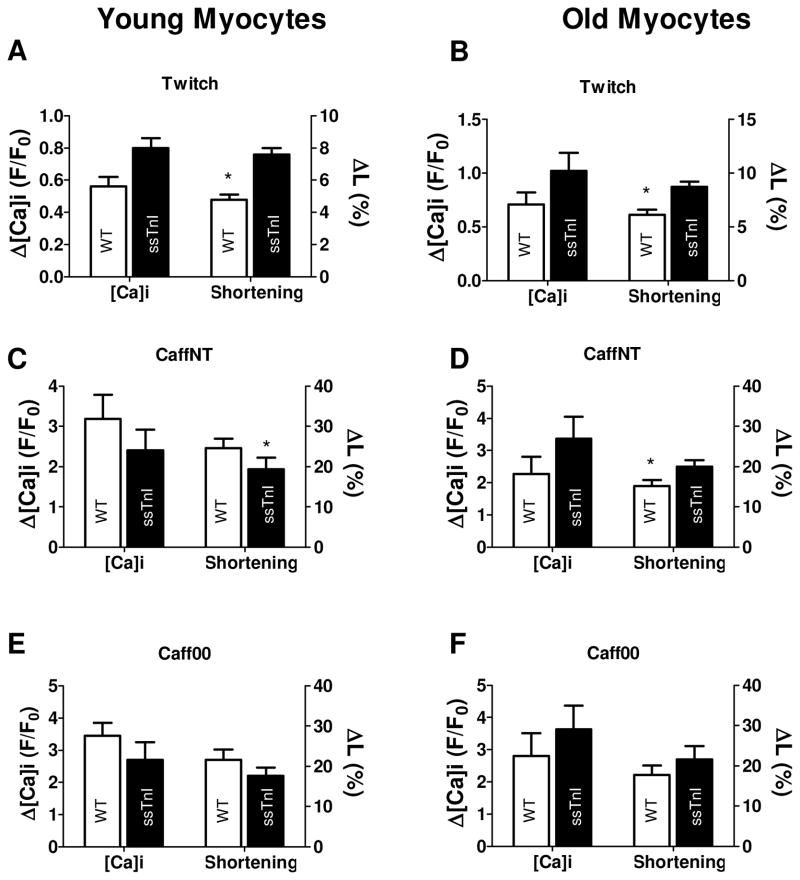

Fig. 2. Ca2+-transients obtained in young and older adult TG-ssTnI and NTG myocytes.

Panels A-C illustrate twitch, CaffNT and Caff00 contracture amplitudes for younger myocytes. Panels D-F show the corresponding relaxation times (tau,τ) for younger myocytes. TG-ssTnI myocytes show bigger (although not significantly different) twitch amplitude (twitch F/F0= 0.80±.0.06 vs 0.56±0.06 NTG). SR Ca2+ content (inferred by the amplitude of caffeine contractures) in young TG-ssTnI cells was not significantly different compared to young NTG myocytes (CaffNT F/F0= 2.40±0.52 vs 3.18±0.60, Caff00 F/F0= 2.70±0.55 vs 3.45±0.40. TG-ssTnI and NTG, respectively). Kinetics of twitch relaxation, as previously shown by Fentzke et al. (19) is relatively slow in TG-ssTnI (twitch τ= 367±39 vs 301±21 ms in NTG, but not significantly different. Both caffeine contractures are significantly faster in young TG-ssTnI (CaffNT τ=2.18±0.23 vs 4.3±0.33 s, p<0.05, Caff00 τ=11.94±1.9 vs 18.0±1.6 s, p<0.05 TG-ssTnI and NTG, respectively). During a twitch, Ca2+ transient amplitude follow the same tendency observed in the younger group, e.g. bigger amplitude but not significantly different between TG-ssTnI and NTG (F/F0= 1.02±0.17.TG-ssTnI vs 0.71±0.11 NTG). Caffeine-induced increased fluorescence levels for the TG-ssTnI group (CaffNT F/F0= 3.37±0.68 vs 2.27±0.53, Caff00 F/F0= 3.63±0.73 vs 2.80±0.72 were not significantly different from NTG (G–I). Relaxation kinetics (J–L) exhibit a slower recovery statistically significant for both caffeine contractures (twitch τ= 390±26 vs 362±32 ms, p> 0.05, CaffNT τ= 4.99±0.54 vs 2.95±0.33 s, p<0.05, Caff00 τ= 17.12±1.5 vs 12.01±1.3 s, p<0.05, TG-ssTnI and NTG, respectively). * indicates p<0.05 between TG and WT.

Data from a series of experiments with the relatively young myocytes are summarized in Figure 2 (Ca2+ transients) and Figure 3 (shortening). In NT, the rate of removal in either Ca2+ transients or shortening traces did not differ significantly. Ca2+ transient amplitude did not show any statistically difference between TG-ssTnI and NTG cells, but shortening was significantly bigger in the TG-ssTnI myocytes..

Fig. 3. Shortening and contracture data obtained in younger and older adult TG-ssTnI and NTG myocytes.

Panels A–C illustrate differences in twitch, CaffNT and Caff00 amplitudes in young mice. Panels D–F show the kinetics of relaxation expressed as t1/2 (D–F). Twitch amplitude is significantly bigger in TG-ssTnI myocytes (7.6±0.4 vs 4.8±0.3% NTG, p<0.05). Caffeine contractures in NT and Na and Ca-free solutions exhibit smaller amplitudes in younger TG-ssTnI myocytes, but this difference is not significant between the two groups (CaffNT: 19.3±2.9 vs 24.6±2.3%, Caff00: 22.1±2.5 vs 27.0±3.2%, n.s TG-ssTnI vs NTG respectively). Twitch relaxation is slow in TG-ssTnI (t1/2 = 245±8.6 vs 206±23 ms NTG), but both caffeine contractures exhibit a significant reduction (CaffNT t1/2= 2.53±0.7 vs 12.3±2.3 s, p<0.01, Caff00 t1/2= 13.21±2.01 vs 25.02±2.9 s, p<0.05, TG-ssTnI vs NTG respectively). The fast re-lengthening of TG-ssTnI cells indicates a bigger relative contribution of the NCX and the slow mechanisms to the relaxation compared to the younger NTG myocytes. Twitch amplitude is significantly bigger in older adult TG-ssTnI mice compared with older NTGmyocytes (8.7±0.5 vs 6.1±0.48%, p<0.05) (G–L). Caffeine applications produced bigger contractures in older TG-ssTnI cells significantly only in the case of caffeine application in NT (CaffNT: 25±2.0 vs 19.0±1.9%, p<0.05. Caff00: 27.0±4.1 vs 22.1±3.0, P>0.05, TG-ssTnI and NTG, respectively). Half-time to relaxation values (t1/2) illustrate a slower twitch for TG-ssTnI (twitch t1/2= 252±26 vs 228±23 ms NTG, P>0.05) and long lasting caffeine contractures (CaffNT t1/2= 20.04±2.12 vs 7.5±1.3 s p<0.01, Caff00 t1/2=30.0±3.5 vs 23.1±2.5 s, P>0.05., TG-ssTnI and NTG respectively). * indicates p<0.05 between TG and WT.

In CaffNT and Caff00 there were no significant differences between the Ca2+ transient amplitude or in percent shortening. But the rate constants for both caffeine applications were significantly faster in TG-ssTnI. These data point out that during relaxation, the contribution of NCX and the slow mechanisms are relatively greater in TG-ssTnI versus NTG in the younger group (Tables I and II).

Table I.

Ca2+ transients, shortening and caffeine contracture amplitudes

| Twitch | CaffNT | Caff00 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ[Ca]i (F/Fo) | Shortening (%) | Δ[Ca]i (F/Fo) | Shortening (%) | Δ[Ca]i (F/Fo) | Shortening (%) | |

| Young | ||||||

| TG-ssTnI | 0.80±0.06 | 7.6±0.4 | 2.40±0.52 | 19.3±2.9 | 2.70±0.55 | 22.1±2.5 |

| NTG-cTnI | 0.56±0.06 | 4.8±0.3 * | 3.18±0.60 | 24.6±2.3 * | 3.45±0.40 | 27.0±3.2 |

| Adult | ||||||

| TG-ssTnI | 1.02±0.17 | 8.7±0.5 | 3.37±0.68 | 25.0±2.0 | 3.63±0.73 | 27.0±4.1 |

| NTG | 0.71±0.11 | 6.1±0.48 * | 2.27±0.53 | 19.0±1.9 * | 2.80±0.72 | 22.1±3.0 |

p<0.05 (NTG relative to TG-ssTnI).

Table II.

Relative contributions to relaxation in young and older adult myocytes.

| SR Ca2+-ATPase (%) | NCX (%) | Slow Mechanisms (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Adult | Young | Adult | Young | Adult | |

| TG-ssTnI | 81.12±2.8 | 92.65±0.63 | 16.02±2.75 | 4.87±0.6 | 3.35±0.42 | 2.5±0.35 |

| NTG | 92.70±1.02 * | 90.9±0.98 | 6.9±0.9 ** | 5.5±0.7 | 1.4±0.09* | 3.4±0.32 |

p<0.05 (NTG relative to TG-ssTnI),

p<0.01 (NTG relative to TG-ssTnI).

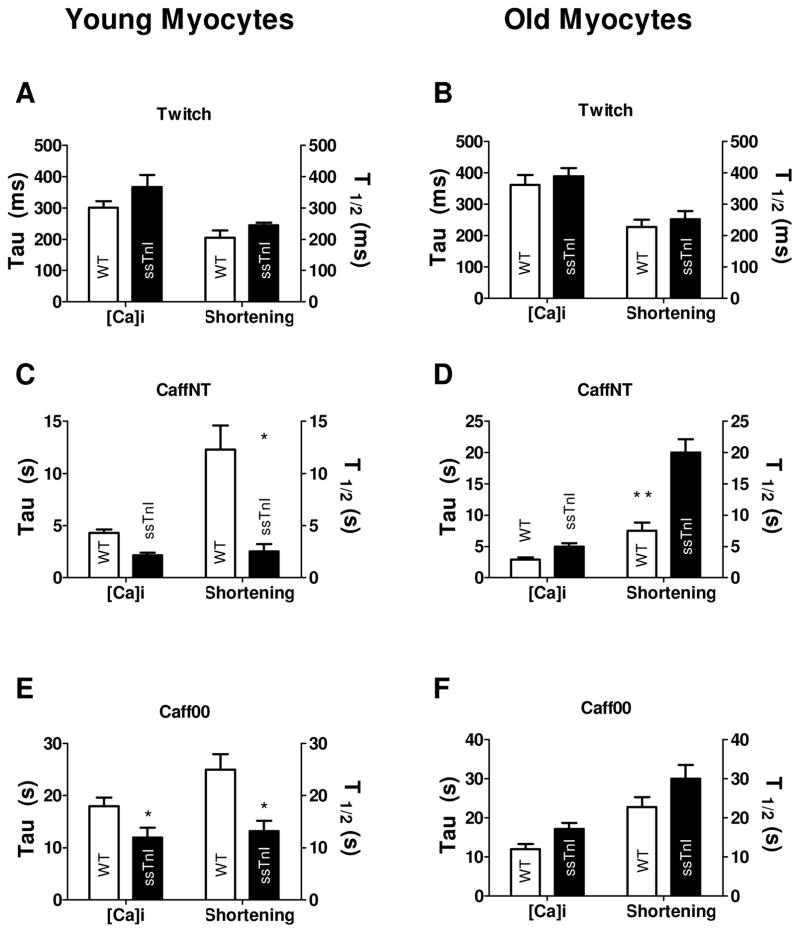

Figure 1 (G–L) shows data from the older group of myocytes using the same protocol applied to the younger group. In the older mice, normal twitch during NT did not show any statistically significant difference in Ca2+ transients amplitude but significantly bigger shortening amplitude in TG-ssTnI vs NTG (Fig 3G) similar to the younger group. During CaffNT and Caff00 applications Ca2+ transients amplitude were the same for both groups (Figs. 2G, H, I). However, the myocytes relaxed more slowly in TG-ssTnI myocytes during applications of both CaffNT and Caff00 (Fig. 2K & L). This result is opposite to that obtained in the younger group in which Ca2+ transients relaxed more quickly in TG-ssTnI during CaffNT or Caff00. The older group of TG-ssTnI myocytes also demonstrated a significant increase in amplitude of cell shortening in CaffNT but not in Caff00 in which both TG-ssTnI and NTG myocytes shortened to the same extent. Data in Figure 4 depict the relative contribution of Ca2+ transporters to relaxation in the younger and older group of TG-ssTnI and NTG myocytes. No differences in percent contribution of transporters were evident in the older group of both TG-ssTnI and NTG myocytes. Nevertheless there were significant differences in percent contribution of Ca2+ transport by the SR Ca2+-ATPase, NCX and the slow mechanisms in the younger group. In this case, there is a reduction in the contribution by the SR Ca2+-ATPase, which is offset by increased contribution of NCX and slow mechanisms.

Fig. 4. Relative contributions to relaxation in younger and older adult myocytes.

Based on the Ca2+ records the contribution of the three major Ca2+ removal mechanisms were estimated as explained in Methods. In the younger TG-ssTnI myocyte population the SR Ca2+-ATPase exhibits a significantly smaller contribution compared to younger NTG myocytes (81.12±2.8% vs 92.7±1.02%, p<0.05). In the older adult population this contribution is significantly different (92.65±0.63% TG-ssTnI, 90.9±0.98% NTG). The NCX participation exhibits a significant increase in the younger TG-ssTnI compared to young NTG (16.02±2.75% TG-ssTnI, 6.9±0.9% NTG, p<0.01). This difference is lost in the adult population where both groups exhibit a similar contribution (4.87±0.6% TG-ssTnI vs 5.5±0.7% NTG). The slow mechanisms also exhibit a bigger contribution in the younger TG-ssTnI myocytes compared to younger NTG (3.5±0.42% vs 1.4±0.09%, p<0.05). In the adult population the participation of the slow mechanism in TG-ssTnI mice decreases to 2.5±0.35%, which is not different from the NTG (3.4±0.32%).

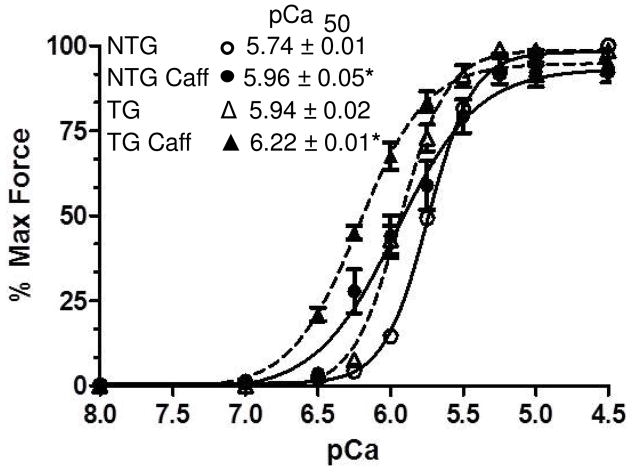

Comparison of effects of caffeine on myofilaments response to Ca2+

Although we have previously demonstrated that caffeine does not affect Ca2+ binding to cardiac TnC [29], it was important to compare the effects of caffeine on the Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments from TG-ssTnI and NTG hearts. Figure 5 shows data from experiments in which we determined the relation between pCa (−log of molar Ca concentration) and tension in detergent extracted fiber bundles. As shown the increase in Ca2+ sensitivity was similar in both TG-ssTnI and NTG myofilaments. Caffeine induced a 0.21 unit shift in the pCa value at 50% activation (pCa50) in the NTG myofilaments and a 0.28 pCa unit shift in the TG-ssTnI myofilaments.

Fig. 5. Comparison of the effects of caffeine on Ca2+-sensitivity of force development in myofilaments of TG-ssTnI and NTG hearts.

Data are normalized to maximum tension achieved before caffeine treatment in the NTG and TG-ssTnI myofilaments. Caffeine did not affect maximum tension in either case. Ca-response is indicated by pCa50. Results demonstrate that the effect of caffeine to increase the response to Ca2+ (differences in pCa50) is the same in myofilaments from NTG controls and TG-ssTnI hearts. * indicates p<0.05 for pCa50 values in the presence of caffeine compared to controls.

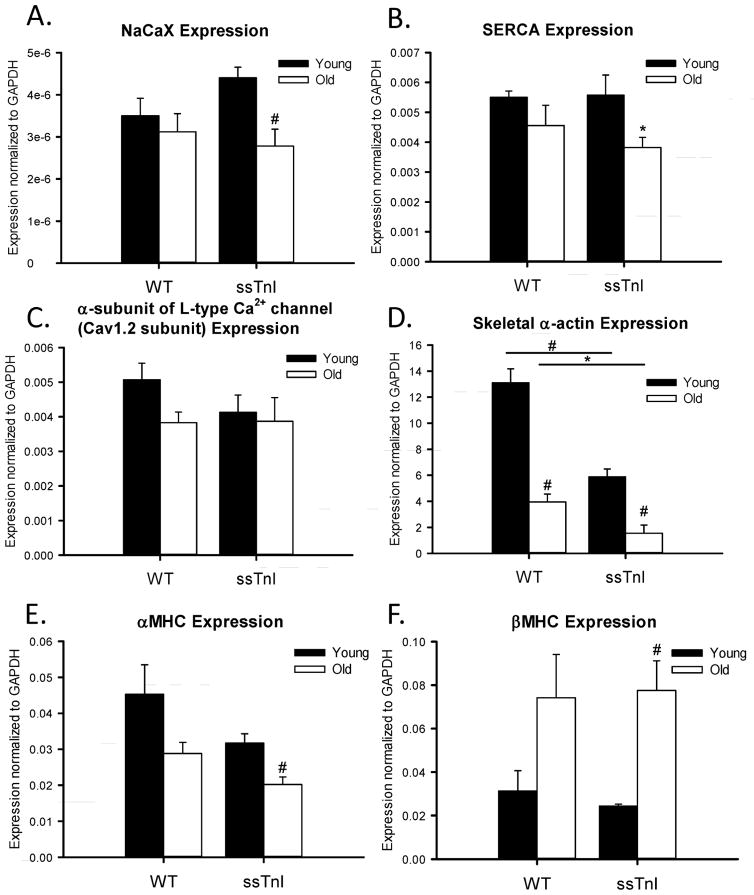

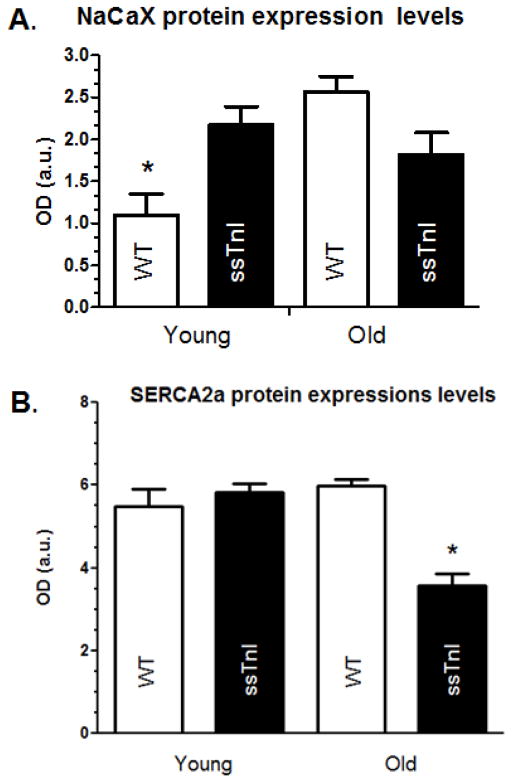

RT-PCR Analysis and Western Blot Analysis

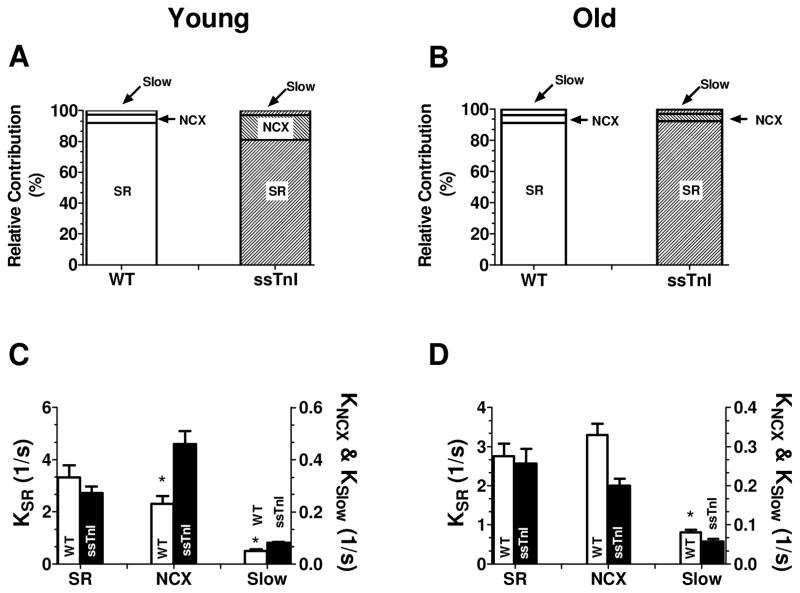

Figure 6 summarizes experiments in which the expression levels of genes important in cellular Ca2+ fluxes (NCX, SERCA2a, L-type Ca2+ channel), and sarcomeric proteins (skeletal alpha-actin, alpha and beta myosin heavy chain) were measured. As illustrated in Figure 6, no significant difference in the NCX, SERCA2a, or L-type Ca2+ channel mRNA expression existed between the TG-ssTnI and NTG hearts. The lack of difference in SERCA2a expression fits with our earlier data [30], demonstrating no difference in SR Ca2+ uptake rate into cardiac SR vesicles in homogenates from TG-ssTnI hearts and NTG controls. The myosin heavy isoform showed characteristic shifts with age, a decrease in alpha-myosin heavy chain expression associated with a reciprocal increase in beta myosin heavy chain. However, the skeletal alpha-actin isoform demonstrated both an age and ssTnI transgene related decline in expression. This isoform was expressed at significantly lower levels in both young and older TG-ssTnI hearts compared to NTG hearts. Data in Figure 7 compare the levels of protein expression of NCX in younger and older hearts from TG-ssTnI and NTG hearts. The young NTG hearts showed significantly lower NCX protein expression than the young TG-ssTnI hearts. Interestingly, the older NTG hearts showed higher NCX expression levels (but not statistically significant) the than the older hearts from TG-ssTnI hearts. These results fit wth the changes in activity seen in these hearts. In the case of younger hearts there was no difference in SERCA2a expression between NTG controls and TG-ssTnI hearts. However, in the older group, expression of SERCA2a was relatively low in TG-ssTnI hearts compared to controls. Despite this difference, we did not see a difference in the per cent contributions of the SR-Ca2+ to relaxation in young versus older TG myocytes.

Fig. 6. Gene expression analysis of young and adult TG-ssTnI and NTG hearts.

Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out on 6 genes: proteins involved in cardiac Ca2+-relaxation ( A. NCX, B. SERCA, and C. alpha subunit of the L-type Ca2+ channel ) and sarcomeric protein isoforms (D. skeletal alpha-actin, E. alpha-myosin heavy chain and F. beta- myosin heavy chain). All results were normalized to GAPDH expression. * indicates p<0.05 and # indicates p<0.01, n=5.

Fig. 7. Quantification of the protein expression levels of NCX (A) and SERCA2a (B) in young and adult TG-ssTnI and NTG hearts.

Western blots were carried out to determine the relative amount of NCX and SERCA2a protein in the different hearts. * indicates p<0.05

DISCUSSION

Our data provide the first evidence of an age dependent modification in the percent contribution of the SR Ca2+-ATPase, NCX, and slow mechanisms to restoration of basal Ca2+ levels after stimulation of cardiac myocytes with constitutive myofilament sensitization to Ca2+. Although we found no differences in expression in the older group, the younger group demonstrated a significant increase in NCX expression in TG-ssTnI versus controls. Moreover, there was a decrease a decrease in expression of SERCA2a between younger and older TG-ssTnI hearts..

We have no detailed signaling mechanism for this difference, but it is apparent that with time the controls catch up with the ssTnI in terms of NCX expression. Moreover, the data indicate that chronic administration of agents acting as Ca-sensitizers (8) may induce altered gene expression.. The data are also highly relevant to FHC. As emphasized in a review by Tardiff (17)there is a need to determine the most proximal disorders, and to design appropriate therapies in the early stages of FHC. In our case, the results indicate early changes in NCX that do not occur in the older myocytes. To our knowledge this possibility has not been well documented or incorporated into ideas regarding the relation between genotype and phenotype in FHC.

Our approach toward dissecting the contribution of each Ca2+ transport system by means of caffeine application has been successfully used to determine the relative participation of the SR Ca2+-ATPase and NCX in relaxation of rabbit and rat cardiac cells [31], with development of the rat heart [32], and at different temperatures [25]. These studies concluded that rabbit hearts depend more on NCX for extrusion of Ca2+ than rat hearts [31], and relaxation dependence on the exchanger diminishes with age in the rat [32]. On the other hand the relative contribution of the SR Ca2+-ATPase and NCX remain about the same as temperature increases from 25 to 35° C. This technique has also been applied in experiments comparing wild type (WT) and mice in which phospholamban was ablated (PLBKO) [33]. In WT myocytes 90% of Ca2+ removal during relaxation was due to the SR Ca2+-ATPase and 8% to the NCX [33]. Results for the NTG myocytes presented here are consistent with these data. In PLBKO mice the SR Ca2+-ATPase values were 96% and NCX values 3.4%. However both PLBKO and WT hearts expressed the same levels of NCX protein and mRNA [34]. In contrast, the mechanism for the difference in NCX activity reported here for the TG-ssTnI and NTG myocytes appear to be due to differences in the amounts of protein expressed in the young and old mice. As reported here, the relative abundance of exchanger protein correlates with the differences we measured in NCX activity.

Our results support the idea that enhanced myofilament sensitivity to Ca2+ may provoke increased expression of the NCX in the younger group of mice. An increase in the expression levels of the exchanger has been reported to occur in hearts at end-stage failure [35] and in animal models of heart failure [36, 37]. These models display abnormalities associated with decreased activity of the SR Ca2+-ATPase together with increased myofilaments sensitivity to Ca2+. Interestingly, the increase NCX activity may be a transient compensation as measurements in hearts of patients apparently closer to death that those studied by Hasenfuss et al. [35] did not display increased NCX activity [38]. The increase in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in human heart failure has been attributed to down regulation of signaling and signal transduction through beta-adrenergic receptors, and a relative dephosphorylation at PKA phosphorylation sites of key myofilament proteins compared to non-failing controls [39]. Myofilaments from hearts of dogs subjected to pacing induced heart failure also demonstrate increased response to Ca2+ by a mechanism possibly also involving dephosphorylation of myosin light chain 2 [40]. In the case of the ssTnI-TG mice, the region of TnI responding to PKA is not present and thus the myofilaments are not only intrinsically more sensitive to Ca2+ than the controls, but also the myofilaments do not desensitize in response to adrenergic stimulation as occurs in the controls. This restriction of a dynamic range of Ca-sensitivity and thus Ca2+ buffering is also likely to be an important aspect of the altered gene expression at least in the younger ssTnI-TG mice in the case of NCX, and in the older group of mice in the case of SERCA2a expression.

Our results are also relevant to mechanisms by which mutations in sarcomeric proteins give rise to hypertrophic cardiomyopathies [13, 17, 41–43]. These mutations are linked to a phenotype exhibiting asymmetric hypertrophy, myocyte disarray and fibrosis. Heart failure is common as are arrhythmias and sudden death [44, 45]. In most cases, the sarcomeric mutations are associated with an increase in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity [46, 47] similar to that demonstrated by the myofilaments from the TG-ssTnI mouse hearts. As with the hearts expressing ssTnI, hearts expressing mutant forms of thin filament proteins such as cTnI [48, 49], cTnT [50, 51] and Tm [52] also demonstrate diastolic abnormalities. One hypothesis is that the increase in Ca2+-sensitivity results in a dominant negative effect on relaxation, causing diastolic abnormalities and triggering of the hypertrophic signaling [53] Another is that altered disposition of Ca2+ in the myocytes signals the hypertrophic process [54].

Although hearts of TG-ssTnI mice do not show hypertrophy or myofilament disarray, changes in SR Ca2+ load and up-regulation of NCX in the younger group of TG-ssTnI mice provide clues as to the processes connecting sarcomeric mutations to sudden death. There is ample evidence that an enhanced activity of the NCX in non-ischemic heart failure is the basis for an arrhythmogenic transient inward current. The reduction in SR Ca2+ load associated with up-regulation of NCX is also likely to be responsible for a reduction in Ca2+ delivery to the myofilaments and depression of contractility in heart failure. In the case of TG-ssTnI hearts, it is apparent that the functional effects of this decrease in Ca2+ released to the myofilaments are offset by an enhanced myofilament response to Ca2+. We propose that the enhanced myofilament sensitivity to Ca2+, as occurs in FHC sarcomeric mutations, leads to increased expression of NCX, as a compensatory mechanism, and thus is an important potential factor in triggered arrhythmias. There have been reports of upregulation of NCX in FHC associated with an E334K mutation in myosin binding protein C [55] and a R92W in cTnT [56]. In the case of the MyBP-C mutation the change was not linked to increased myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity, and in the TnT mutation there was no correlation with altered activity of the NCX.

Findings reported here are of significance with regard to a recent novel hypothesis linking increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity to triggered arrhythmias. Huke et al. [57] reported that myofilaments of an FHC model with relatively high Ca-sensitivity induce a localized, focal increase in ATP demand resulting in a loss of energy supply and a pro-arrhythmic reduction in gap junction coupling. These effects occurred in a cTnT-I79N model, similar to TG-ssTnI, exhibiting increased myofilament sensitization to Ca2+, but without hypertrophy. No measurements similar to those carried out here with the TG-ssTnI myocytes have been done. Thus it remains possible that changes in Ca2+ may exacerbate the effects of the localized energy deprivation. In both the TG-ssTnI and TG-I79N model arrhythmias are induced by isoproterenol challenge [18, 57]. It is unlikely though that an energy deprivation is responsible for the arrhythmias in the ssTnI model, which undergoes metabolic remodeling resulting in increased glycolysis compared to controls. We have previously demonstrated that TG-ssTnI hearts are highly resistant to global ischemia with preservation of ATP concentration as a result of increased glycolysis [22]. We think in the case of TG-ssTnI hearts it is highly unlikely that there are localized energy deficits, and that remodeling of Ca2+ fluxes is more likely to be responsible. Mutations in cTnT are well documented to alter Ca-fluxes and expression of proteins significantly affecting Ca-fluxes [17, 56]. In the case of the cTnT-R92W mutation compared to NTG controls there is also an increase in NCX expression at 6 month of age, but no correlation with NCX activity [56]. Acute administration of the Ca-sensitizing agent EMD also induces arrhythmias associated with focal energy deficits [57], but no studies have been carried out testing whether chronic administration also induces remodeling of Ca-flux mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

Individuals with FHC generally die young, and we think our data adds to our understanding of the role of increased myofilament Ca-sensitivity. We report that there are differences in Ca2+ transport mechanisms between NTG and TG-ssTnI myocytes that are a function of age. The most striking difference is in the NCX that changes from a contribution to Ca2+ of 16% in young TG-ssTnI mice to 5% in an adult TG-ssTnI. In both the younger and older groups of TG-ssTnI myocytes, our data also indicate the possibility of a lower SR Ca2+ load. A lower SR Ca2+ load would be expected to reduce the possible induction of spontaneous release of Ca2+ from the SR with arrhythmogenic consequences [58]. This may seem a contradiction to our conclusion inasmuch as a However, previous studies have demonstrated that the increase in myofilament Ca-sensitivity in the ssTnI heart does induce arrhythmias and creates an arrhythmogenic substrate [18]. Our data support the possibility that modifications in Ca2+ fluxes in FHC and TG-ssTnI myocytes act in concert with chronically increased myofilament response to Ca2+ to generate arrhythmias leading to sudden death.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Persistent increases in myofilament Ca-sensitivity induce altered Ca-fluxes

The changes in Ca-fluxes are age dependent.

A change in NCX activity and expression is prominent and affects relaxation.

There are also changes in SR Ca2 load, which may be functionally significant.

Alterations induced by increased myofilament Ca-response may induce arrhythmias.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. Lynn Wang and Anne Martin for their help in management of the mouse colonies and for help with the early phases of the experiments. Grant support was NIH RO1 HL 022231 and PO1 HL 062426 (RJS), R37 HL030077 (DMB), R01 HL096819 (AVG), and American Heart Association (JLP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bers DM, Guo T. Calcium signaling in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:86–98. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson ME, Brown JH, Bers DM. CaMKII in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:468–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solaro RJ, Henze M, Kobayashi T. Integration of troponin I phosphorylation with cardiac regulatory networks. Circ Res. 2013;112:355–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kranias EG, Bers DM. Calcium and cardiomyopathies. Sub-cellular biochemistry. 2007;45:523–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kusakari Y, Hongo K, Kawai M, Konishi M, Kurihara S. Use of the Ca-shortening curve to estimate the myofilament responsiveness to Ca2+ in tetanized rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol Sci. 2006;56:219–26. doi: 10.2170/physiolsci.RP003706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saeki Y, Kurihara S, Hongo K, Tanaka E. Alterations in intracellular calcium and tension of activated ferret papillary muscle in response to step length changes. J Physiol. 1993;463:291–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurihara S, Saeki Y, Hongo K, Tanaka E, Sudo N. Effects of length change on intracellular Ca2+ transients in ferret ventricular muscle treated with 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM) Jpn J Physiol. 1990;40:915–20. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.40.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai M, Lee JA, Orchard CH. Effects of the Ca2+ sensitizer EMD 57033 on intracellular Ca2+ in rat ventricular myocytes: relevance to arrhythmogenesis during positive inotropy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;99:547–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westfall MV, Solaro RJ. Alterations in myofibrillar function and protein profiles after complete global ischemia in rat hearts. Circ Res. 1992;70:302–13. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann PA, Miller WP, Moss RL. Altered calcium sensitivity of isometric tension in myocyte-sized preparations of porcine postischemic stunned myocardium. Circ Res. 1993;72:50–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomes AV, Potter JD. Molecular and cellular aspects of troponin cardiomyopathies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:214–24. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tardiff JC. Sarcomeric proteins and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: linking mutations in structural proteins to complex cardiovascular phenotypes. Heart Fail Rev. 2005;10:237–48. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marston SB. How do mutations in contractile proteins cause the primary familial cardiomyopathies? J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011;4:245–55. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biesiadecki BJ, Tachampa K, Yuan C, Jin JP, de Tombe PP, Solaro RJ. Removal of the cardiac troponin I N-terminal extension improves cardiac function in aged mice. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19688–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.086892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sequeira V, Wijnker PJ, Nijenkamp LL, Kuster DW, Najafi A, Witjas-Paalberends ER, et al. Perturbed length-dependent activation in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with missense sarcomeric gene mutations. Circ Res. 2013;112:1491–505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jagatheesan G, Rajan S, Petrashevskaya N, Schwartz A, Boivin G, Arteaga GM, et al. Rescue of tropomyosin-induced familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mice by transgenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H949–58. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01341.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tardiff JC. Thin filament mutations: developing an integrative approach to a complex disorder. Circ Res. 2011;108:765–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baudenbacher F, Schober T, Pinto JR, Sidorov VY, Hilliard F, Solaro RJ, et al. Myofilament Ca2+ sensitization causes susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmia in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3893–903. doi: 10.1172/JCI36642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fentzke RC, Buck SH, Patel JR, Lin H, Wolska BM, Stojanovic MO, et al. Impaired cardiomyocyte relaxation and diastolic function in transgenic mice expressing slow skeletal troponin I in the heart. J Physiol. 1999;517 ( Pt 1):143–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0143z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolska BM, Vijayan K, Arteaga GM, Konhilas JP, Phillips RM, Kim R, et al. Expression of slow skeletal troponin I in adult transgenic mouse heart muscle reduces the force decline observed during acidic conditions. J Physiol. 2001;536:863–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urboniene D, Dias FA, Pena JR, Walker LA, Solaro RJ, Wolska BM. Expression of slow skeletal troponin I in adult mouse heart helps to maintain the left ventricular systolic function during respiratory hypercapnia. Circ Res. 2005;97:70–7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173849.68636.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pound KM, Arteaga GM, Fasano M, Wilder T, Fischer SK, Warren CM, et al. Expression of slow skeletal TnI in adult mouse hearts confers metabolic protection to ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolska BM, Solaro RJ. Method for isolation of adult mouse cardiac myocytes for studies of contraction and microfluorimetry. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1250–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassani RA, Bassani JW, Bers DM. Relaxation in ferret ventricular myocytes: role of the sarcolemmal Ca ATPase. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:573–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00373894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puglisi JL, Bassani RA, Bassani JW, Amin JN, Bers DM. Temperature and relative contributions of Ca transport systems in cardiac myocyte relaxation. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1772–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solaro RJ, Varghese J, Marian AJ, Chandra M. Molecular mechanisms of cardiac myofilament activation: modulation by pH and a troponin T mutant R92Q. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97 (Suppl 1):I102–10. doi: 10.1007/s003950200038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alden KJ, Goldspink PH, Ruch SW, Buttrick PM, Garcia J. Enhancement of L-type Ca(2+) current from neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes by constitutively active PKC-betaII. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C768–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00494.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierce KE, Rice JE, Sanchez JA, Brenner C, Wangh LJ. Real-time PCR using molecular beacons for accurate detection of the Y chromosome in single human blastomeres. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:1155–64. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.12.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers FM, Solaro RJ. Caffeine alters cardiac myofilament activity and regulation independently of Ca2+ binding to troponin C. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C1348–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.6.C1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dias FA, Walker LA, Arteaga GM, Walker JS, Vijayan K, Pena JR, et al. The effect of myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation on the frequency-dependent regulation of cardiac function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:330–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassani JW, Bassani RA, Bers DM. Relaxation in rabbit and rat cardiac cells: species-dependent differences in cellular mechanisms. J Physiol. 1994;476:279–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bassani RA, Bassani JW. Contribution of Ca(2+) transporters to relaxation in intact ventricular myocytes from developing rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2406–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00320.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Chu G, Kranias EG, Bers DM. Cardiac myocyte calcium transport in phospholamban knockout mouse: relaxation and endogenous CaMKII effects. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1335–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.4.H1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu G, Ferguson DG, Edes I, Kiss E, Sato Y, Kranias EG. Phospholamban ablation and compensatory responses in the mammalian heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;853:49–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasenfuss G, Schillinger W, Lehnart SE, Preuss M, Pieske B, Maier LS, et al. Relationship between Na+-Ca2+-exchanger protein levels and diastolic function of failing human myocardium. Circulation. 1999;99:641–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pogwizd SM, Qi M, Yuan W, Samarel AM, Bers DM. Upregulation of Na(+)/Ca(2+) exchanger expression and function in an arrhythmogenic rabbit model of heart failure. Circ Res. 1999;85:1009–19. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei SK, Ruknudin A, Hanlon SU, McCurley JM, Schulze DH, Haigney MC. Protein kinase A hyperphosphorylation increases basal current but decreases beta-adrenergic responsiveness of the sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in failing pig myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;92:897–903. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069701.19660.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piacentino V, 3rd, Weber CR, Chen X, Weisser-Thomas J, Margulies KB, Bers DM, et al. Cellular basis of abnormal calcium transients of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;92:651–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000062469.83985.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolff MR, Whitesell LF, Moss RL. Calcium sensitivity of isometric tension is increased in canine experimental heart failure. Circ Res. 1995;76:781–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suematsu N, Satoh S, Ueda Y, Makino N. Effects of calmodulin and okadaic acid on myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity in cardiac myocytes. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97:137–44. doi: 10.1007/s003950200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marian AJ. Genetic determinants of cardiac hypertrophy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23:199–205. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3282fc27d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alcalai R, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from bench to the clinics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:104–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudsmith LE, Petersen SE, Francis JM, Robson MD, Watkins H, Neubauer S. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Noonan Syndrome closely mimics familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to sarcomeric mutations. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2006;22:493–5. doi: 10.1007/s10554-005-9034-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ly HQ, Greiss I, Talakic M, Guerra PG, Macle L, Thibault B, et al. Sudden death and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a review. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:441–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keren A, Syrris P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the genetic determinants of clinical disease expression. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:158–68. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang B, Chung F, Qu Y, Pavlov D, Gillis TE, Tikunova SB, et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related cardiac troponin C mutation L29Q affects Ca2+ binding and myofilament contractility. Physiol Genomics. 2008;33:257–66. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00154.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LeWinter MM. Functional consequences of sarcomeric protein abnormalities in failing myocardium. Heart Fail Rev. 2005;10:249–57. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kokado H, Shimizu M, Yoshio H, Ino H, Okeie K, Emoto Y, et al. Clinical features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by a Lys183 deletion mutation in the cardiac troponin I gene. Circulation. 2000;102:663–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kimura A, Harada H, Park JE, Nishi H, Satoh M, Takahashi M, et al. Mutations in the cardiac troponin I gene associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 1997;16:379–82. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montgomery DE, Tardiff JC, Chandra M. Cardiac troponin T mutations: correlation between the type of mutation and the nature of myofilament dysfunction in transgenic mice. J Physiol. 2001;536:583–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0583c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lombardi R, Bell A, Senthil V, Sidhu J, Noseda M, Roberts R, et al. Differential interactions of thin filament proteins in two cardiac troponin T mouse models of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:109–17. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michele DE, Metzger JM. Physiological consequences of tropomyosin mutations associated with cardiac and skeletal myopathies. J Mol Med. 2000;78:543–53. doi: 10.1007/s001090000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmad F, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. The genetic basis for cardiac remodeling. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:185–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solaro RJ, Montgomery DM, Wang L, Burkart EM, Ke Y, Vahebi S, et al. Integration of pathways that signal cardiac growth with modulation of myofilament activity. J Nucl Cardiol. 2002;9:523–33. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2002.127626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bahrudin U, Morikawa K, Takeuchi A, Kurata Y, Miake J, Mizuta E, et al. Impairment of ubiquitin-proteasome system by E334K cMyBPC modifies channel proteins, leading to electrophysiological dysfunction. J Mol Biol. 2011;413:857–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guinto PJ, Haim TE, Dowell-Martino CC, Sibinga N, Tardiff JC. Temporal and mutation-specific alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis differentially determine the progression of cTnT-related cardiomyopathies in murine models. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H614–26. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01143.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huke S, Venkataraman R, Faggioni M, Bennuri S, Hwang HS, Baudenbacher F, et al. Focal energy deprivation underlies arrhythmia susceptibility in mice with calcium-sensitized myofilaments. Circ Res. 2013;112:1334–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001;88:1159–67. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]