Abstract

Background

One of the hallmark features of major depressive disorder (MDD) is reduced reward anticipation. There have been mixed findings in the literature as to whether reward anticipation deficits in MDD are related to diminished mesolimbic activation and/or enhanced dorsal anterior cingulate activation (dACC). One of the reasons for these mixed findings is that these studies have typically not addressed the role of comorbid anxiety, a class of disorders which frequently co-occur with depression and have a common neurobiology.

Methods

The aim of the current study was to examine group differences in neural responses to reward anticipation in 40 adults with either: 1) current MDD with no lifetime diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (MDD-only), 2) current MDD with comorbid panic disorder (MDD-PD), or 3) no lifetime diagnosis of psychopathology. All participants completed a passive slot machine task during a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scan.

Results

Analyses indicated that there were no group differences in activation of mesolimbic reward regions; however, the MDD-only group exhibited greater dACC activation during the anticipation of rewards compared with the healthy controls and the comorbid MDD-PD group (who did not differ from each other).

Limitations

The sample size was small which limits generalizability.

Conclusions

These findings provide preliminary support for the role of hyperactive dACC functioning in reduced reward anticipation in MDD. They also indicate that comorbid anxiety may alter the association between MDD and neural responding to reward anticipation.

Keywords: major depressive disorder, reward anticipation, panic disorder, anterior cingulate cortex

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the world’s most common illnesses and currently affects over 16% of the general population (Hasin et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2003). Enormous personal and societal costs are associated with MDD, and it is predicted that depression will be the leading global cause of poor health by 2030 (Lépine and Briley, 2011). Despite the high prevalence and devastating impact of MDD, its underlying neurobiology is still not well understood. Consequently, there is a growing need to elucidate neural processes which contribute to depressive disorders in hopes of identifying biomarkers for outcomes and developing more targeted interventions.

A large body of evidence suggests that individuals with depression exhibit reward processing deficits (Epstein et al., 2006; Pizzagalli et al., 2009a; Wacker et al., 2009; see Bylsma et al., 2008 for a review). It is important to note, however, that reward processing is a broad construct and can be divided into two distinct, temporal components - reward anticipation and reward consummation (Berridge and Robinson, 2003; Gard et al., 2006). Reduced reward anticipation, or a diminished tendency to expect and/or approach rewards, has long been argued to be a core feature of depressive disorders (Davidson, 1998; Meehl, 1975), and this premise has been supported by numerous behavioral and psychophysiological studies (Treadway et al., 2009; Shankman et al., 2013). A recent study has also suggested that the broad reward-related abnormalities in depression are primarily driven by deficits in reward anticipation and not reward consummation (Sherdell et al., 2012).

Across human and animal imaging studies, the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway has been most often implicated in reward anticipation (see Haber and Knutson, 2010). The pathway originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projects to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) of the ventral striatum, as well as the dorsal striatum, amygdala, and medial prefrontal cortex (Knutson et al., 2001; Tsurugizawa et al., 2012). Several neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that individuals with depression exhibit reduced activation in mesolimbic regions during reward anticipation compared to healthy controls. For example, using a ‘Wheel of Fortune’ decision-making task, Smoksi and colleagues (2009) found that relative to controls, MDD participants showed decreased activation in the right caudate during reward anticipation. In a separate study, using a monetary incentive delay task (MID), Pizzagalli et al. (2009b) reported that MDD participants displayed reduced activation in the left putamen while anticipation a reward.

In addition to hyporesponsivity in mesolimbic structures, researchers have speculated that the reward processing deficits in MDD may also be associated with hyperresponsivity of cortical regions associated with conflict monitoring (Liu et al., 2011). Depressed individuals expect positive outcomes to a lesser extent than non-depressed individuals (Alloy and Ahrens, 1987; Beck and Clark, 1998), which is thought to create an affective conflict (or incongruence) during reward anticipation. Affective conflict has repeatedly been shown to be associated with enhanced dorsal anterior cingulate cortex suggesting that this region may also be associated with reward anticipation deficits in individuals with depression (dACC; Botvinick et al., 1999; Ochsner et al., 2009; Shackman et al., 2011). In line with this hypothesis, Knutson and colleagues (2008) reported that depressed and non-depressed individuals both exhibited activation of the ventral striatum (including the NAc) during anticipation of reward, but those with MDD displayed significantly greater dACC activation compared with controls. In other words, hyperactive dACC activity, and not hypoactive mesolimbic activity, differentiated the depressed and non-depressed participants.

It is important to note that the findings from Knutson et al. (2008) have not been consistently replicated and several studies have found no difference in dACC activation between MDD and non-MDD participants during reward anticipation (e.g., Smoski et al., 2009; Smoski et al., 2011). There are several potential explanations for these discrepant findings. First, there are important differences among task paradigms that examine reward anticipation that could impact neural responding. For instance, Knutson et al. (2008) used the MID task, a paradigm that requires participants to press a button in-order to gain or avoid losing money. As such, there was a behavioral component to their design which may be affected by the psychomotor deficits often seen in depressed individuals (Sobin and Sackeim, 1997). Smoski et al.’s (2009) task did not have a behavioral component but did contain aspects of decision-making, as participants were asked to choose between two options, with different probabilities of winning each trial. Importantly, no study to our knowledge has investigated the neural correlates of reward anticipation within currently depressed individuals using a task that does not require a motor response or decision (i.e., completely passive task).

The role of comorbid anxiety disorders is another factor that could contribute to prior mixed findings. Although depressive and anxiety disorders commonly co-occur (Kessler et al., 1996; Mineka et al., 1998), the effect of anxiety on neural responding during reward anticipation is poorly understood. In a sample of adolescents, it was previously demonstrated that like those with depression, anxious individuals displayed reduced activation in the striatum compared with controls (Forbes et al., 2006). Unlike those with depression, however, anxious participants also displayed enhanced orbital frontal cortex (OFC) activation. Bar-Haim and colleagues (2009) found that adolescents with elevated anxiety symptoms exhibited enhanced striatal response to reward anticipation relative to non-anxious youth. More recently, a study of adults reported no differences in neural responding during anticipation of rewards between controls and those with obsessive-compulsive-disorder (OCD; Choi et al., 2012). Given that these studies examined depression and anxiety separately, prior findings may not speak to the impact of MDD with comorbid anxiety. To date, there has been no study to our knowledge that has directly compared individuals with MDD-only and MDD with comorbid anxiety on neural responses to reward anticipation. Interesting, in the broader depression-anxiety psychophysiology literature, the findings are also mixed; however, several studies have found that having a comorbid disorder attenuates the typical response of the primary disorder (Weinberg et al., 2012; Kentgen et al., 2000). Thus, it is possible that a similar effect would be seen in investigations of neural responding.

Given the gaps in the existing literature, the aim of the current study was to examine neural responses to reward anticipation using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in three groups: 1) current MDD, 2) current MDD with comorbid panic disorder (PD), and 3) no lifetime history of psychopathology. We used a completely passive, slot machine paradigm to attempt to reduce the role of motor responding on affective responses. We hypothesized that individuals with MDD-only would displayed reduced NAc/ventral striatum and enhanced dACC activation during reward anticipation relative to controls. Although there was very little existing data to inform our hypotheses about the effect of comorbid MDD and PD, we postulated that PD may moderate the relation between MDD and neural responding. Specifically, we speculated that the comorbid group would exhibit greater NAc/ventral striatum and reduced dACC activation relative to the MDD-only group.

Methods

Participants

The present study included 40 right-handed adults with: 1) current MDD with comorbid PD (n = 13), 2) current MDD with no lifetime diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (n = 9), and 3) no lifetime history of psychopathology (n = 18). All participants were recruited from the community and enrolled in a larger study on emotional deficits in depression and anxiety (Shankman et al., 2013). Current and past diagnoses were made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 1996). Participants in the comorbid group were allowed to have additional current or past anxiety disorders. Participants in the MDD-only group were required to have no current or past anxiety disorder. Interrater reliabilities of SCID diagnoses were conducted on a subset of participants and indicated perfect diagnostic agreement (all Kappas = 1.00). Individuals were excluded from the larger study if they had a lifetime diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, or dementia; were unable to read or write in English; had a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness; or were left-handed (as confirmed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory; range of laterality quotient: +20 to +100; Oldfield, 1971). All methods were approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Procedure and Reward Anticipation Task

After providing written informed consent, all participants completed a mock scan and a practice version of the experimental task. Approximately 7 days later, they returned for their fMRI scan. All scanning sessions took place between 7am and 12pm and participants were instructed to abstain from caffeine and tobacco for at least two hours prior to their scan.

The reward anticipation task was a computerized, passive slot machine paradigm with two conditions – reward (R) and no incentive (NI). In both conditions, a ring of geometric shapes would ‘spin’ on the screen and then ‘land’ on a result. In the R condition, participants won money if it landed on an image of a birthday cake but did not lose money if it landed on something else. In the NI condition, participants continued to play the game, but their earnings did not change regardless of outcome (i.e., there was no incentive). The task included 2 runs of 32 trials that were equally divided into R and NI conditions. Each time, the reels would spin for 4–6 seconds and participants would view the result for 3-seconds. Conditions (R or NI) were presented in 30-second blocks, and the total task time was approximately 12-minutes. Between conditions a fixation cross was presented for 10-seconds to allow the fMRI blood oxygenated level-dependent (BOLD) signal to return to baseline. At the end of the task, all participants were given their winnings of $17 in cash.

Prior to the fMRI scan, participants completed the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS; Watson et al., 2007). The IDAS is a 64-item self-report measure of symptoms of anxiety and depression during the previous two weeks. Participants are asked to respond to each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). In addition to providing total depression and dysthymia scores, the IDAS yields 10 symptom subscales including: suicidality, lassitude, insomnia, appetite loss, appetite gain, ill-temper, well-being, panic, social anxiety, and traumatic intrusions. Prior research has demonstrated that the IDAS has excellent psychometric properties including internal consistently, test-retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity (Watson et al., 2007).

fMRI Data Acquisition

Functional MRI was performed on a 3T GE magnetic resonance scanner at the University of Illinois Medical Center. Functional images were acquired using a gradient-echo echo-planar images (2s TR, 25ms TE, 82° flip, 64×64 matix, 200 mm FOV, 3mm slice thickness, 0mm gap, with 40 axial slices). A high-resolution, T1-weighted anatomical scan was also acquired in the same axial orientation (25° flip; 512×512 matrix, 220mm FOV; 1.5mm slice thickness; 120 axial slices).

fMRI Data Processing and Analyses

Data from all 40 participants met criteria for high quality and scan stability with minimum motion correction (i.e., 3 mm or less displacement in any one direction) and thus were included in subsequent analyses. Functional data were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM8, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuro-Science, London, UK). Images were spatially realigned to correct for head motion, warped to standardized Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using the participants' T1 image, resampled to 2 mm3 voxels, and smoothed with an 8 mm3 kernel to minimize noise and residual differences in gyral anatomy. The general linear model was applied to the time series, convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function and with a 128-s high-pass filter. Condition effects were modeled with box-car regressors representing the occurrence of each block type. Effects were estimated at each voxel and for each subject.

Individual contrast maps (statistical parametric maps) for R condition spins (i.e., reward anticipation) greater than NI condition spins were generated for each participant. Contrast maps for the healthy controls were first entered into a second-level one-sample t-test to determine the effects of the task on a healthy population. Next, contrast maps were entered into a second-level analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether there was an effect of group. Age was included as a covariate in the ANOVA. Because of our strong a priori hypotheses about the role of the NAc/ventral striatum and dACC, we created an anatomically-derived (AAL atlas) partial brain mask of these regions and applied a cluster-based significance thresholding to adjust for multiple comparisons within the search volume. Based on simulations (10,000 iterations) performed with AlphaSim (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub/dist/doc/manual/AlphaSim.pdf), a family wise error correction at α < 0.05 is achieved with a voxel threshold of p < 0.005 and a cluster size of at least 115 voxels. As an exploratory aim, we also conducted a whole-brain second-level ANOVA and considered activations that survived p < 0.005 (uncorrected), with a cluster extent threshold of greater than 20 contiguous voxels (volume > 160mm3), as significant to balance between Type I and Type II error (Lieberman et al., 2009). In-order to clarify the direction of condition effects, we extracted BOLD signal responses (i.e., parameter estimates, β weights [arbitrary units]) from 5 mm (radius) spheres surrounding significant peak activations to conduct post hoc independent samples t-tests.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Group differences in demographics and clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1. Of note, participants in the MDD-only and MDD-PD groups were matched on depression severity (i.e., Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression [Hamilton, 1960], and IDAS depression), and, as expected, both groups reported greater depressive symptoms than those in the control group.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Controls (n = 18) |

MDD-only (n = 9) |

MDD-PD (n = 13) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| Age (years; SD) | 29.5 (13.1)a | 25.4 (7.7)a | 39.1 (11.9)b |

| Sex (% female) | 72.2%a | 66.7%a | 76.9%a |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 55.6%a | 22.2%a | 41.7%a |

| Education | |||

| Graduated high school or GED | 5.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Part college or graduated 2 year college | 22.2% | 55.6% | 50.0% |

| Graduated 4 year college | 44.4% | 33.3% | 33.3% |

| Part or completed graduate/ professional school | 27.8% | 11.1% | 16.6% |

| Current Comorbid Diagnoses | |||

| Social Phobia | - | - | 23.1% |

| Specific Phobia | - | - | 7.7% |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | - | - | 7.7%a |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | - | - | 0.0%a |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | - | - | 7.7%a |

| Past Diagnoses | |||

| Alcohol Abuse | 11.1%a | 0.0%a | 15.4%a |

| Alcohol Dependence | 0.0%a | 11.1%a | 23.1%b |

| Substance Abuse | 0.0%a | 11.1%a | 0.0%a |

| Substance Dependence | 0.0%a | 0.0%a | 23.1%b |

| Clinical variables | |||

| Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; SD) | 87.3 (8.2)a | 52.4 (10.0)b | 51.6 (6.3)b |

| Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression (HRSD; SD) | 2.4 (3.6)a | 26.3 (8.4)b | 28.2 (5.6)b |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; SD) | 2.4 (3.1)a | 12.0 (7.0)b | 20.0 (11.7)c |

| IDAS – Depression | 28.1 (5.5)a | 55.4 (18.3)b | 56.3 (12.8)b |

| IDAS-Suicidality | 6.1 (0.5)a | 9.4 (4.5)b | 7.0 (1.5)a |

| Current psychiatric medications | 0.0%a | 11.1%a | 30.8%b |

Note. Means or percentages with different subscripts across rows were significantly different in pairwise comparisons (p < .05, chi-square test for categorical variables and Tukey’s honestly significant difference test for continuous variables).

Controls = individuals with no history of psychopathology; MDD-only = individuals with current major depressive disorder and no history of anxiety disorders; MDD-PD = individuals with current comorbid major depressive disorder and panic disorder; IDAS = Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms; SD = Standard deviation

Effect of Reward Task

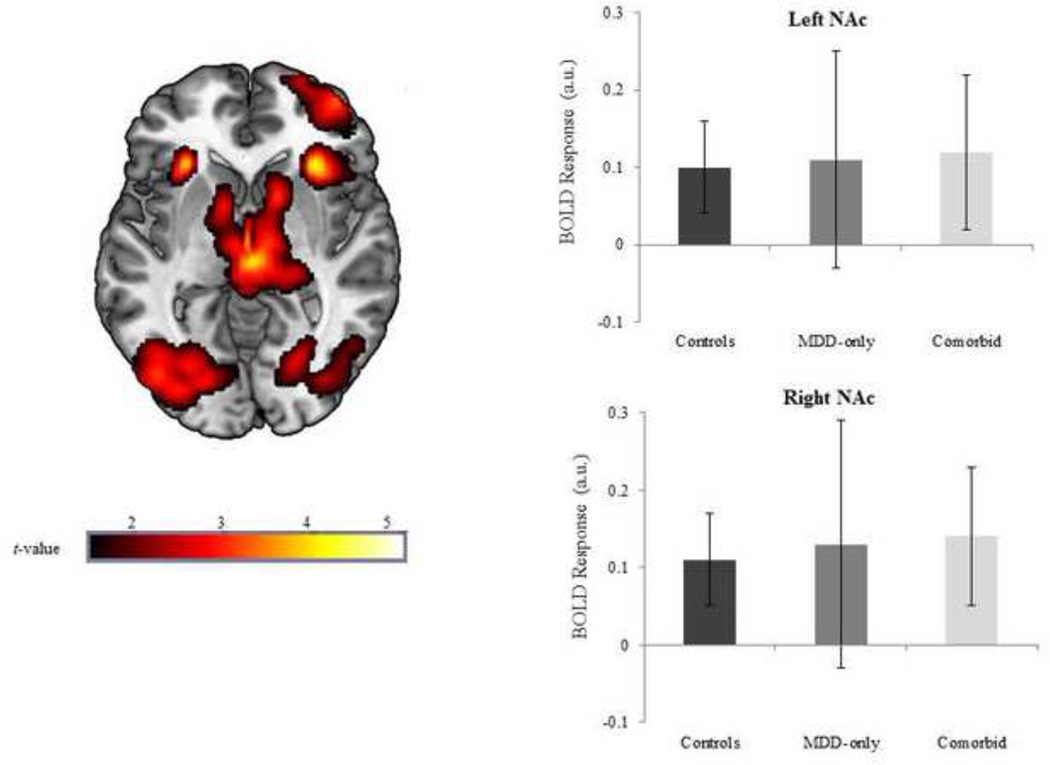

Whole-brain results indicated that within healthy controls, anticipation of reward (R condition spins > NI condition spins) significantly activated a large contiguous cluster of mesolimbic reward regions including bilateral NAc, caudate, lateral globus pallidum, and putamen (peak MNI [−12, 6, −4], k = 3081, Z = 4.26, p < 0.0001). This suggests that the task successfully probed reward-related regions. Of note, we extracted BOLD signal responses, across all participants, using left and right NAc anatomical masks to further characterize the effects of the task (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Voxel-wise statistical t-map on a canonical brain displaying the effect of reward anticipation in healthy controls; Color scale reflects t-value. Bar graph illustrating extracted parameter estimates from the left and right nucleus accumbens (NAc) during anticipation of reward > no incentive in each group; Controls = no history of psychopathology; MDD-only = current diagnosis of major depressive disorder and no lifetime history of an anxiety disorder; Comorbid = current diagnoses of major depressive disorder and panic disorder.

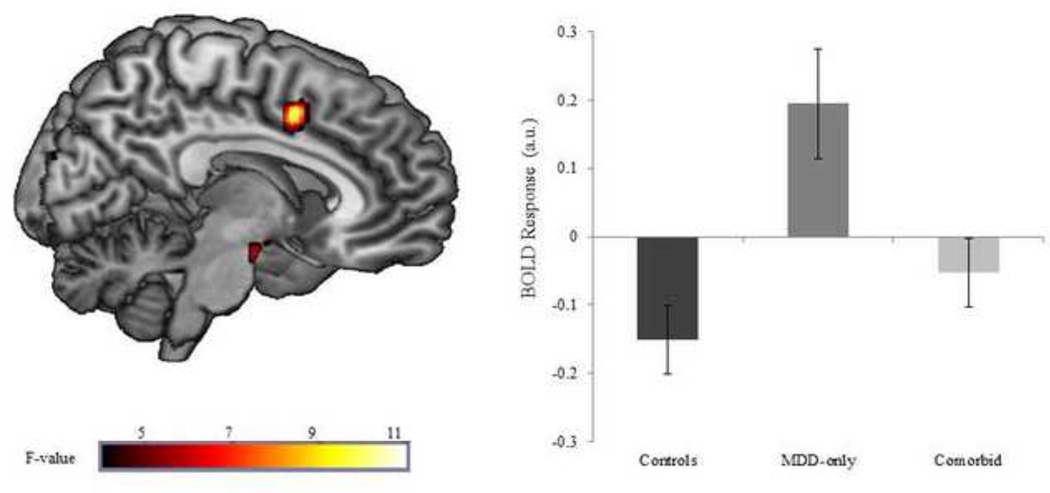

Group Differences in Neural Responding

Results indicated that the groups differed in right dACC activation (MNI peak: [8, 8, 44], Z = 3.43, p < 0.001, 116 contiguous voxels) during anticipation of reward (see Figure 2). Follow-up analyses revealed that the MDD-only group displayed significantly greater dACC activation compared with controls (t(25) = 4.20, p < 0.001) and comorbid individuals (t(20) = 2.62, p < 0.05). The controls and comorbid individuals did not differ from each other (t(29) = 1.40, p = 0.17).

Figure 2.

Voxel-wise statistical F-map on a canonical brain displaying group differences in reward anticipation; Color scale reflects F-value. Bar graph illustrating extracted parameter estimates from the dorsal anterior cingulate (dACC) during anticipation of reward > no incentive in each group; Controls = no history of psychopathology; MDD-only = current diagnosis of major depressive disorder and no lifetime history of an anxiety disorder; Comorbid = current diagnoses of major depressive disorder and panic disorder.

Secondary, whole-brain analyses indicated that the groups also differed on brainstem activation (MNI [2, −6, −22], Z = 3.64, p < 0.005; CON = MDD-only > MDD-PD). There were no other significant results.

Using Pearson’s correlations, post-hoc we examined whether dACC activation was correlated with self-reported IDAS scores across all participants. Results indicated that greater right dACC activation was associated with greater current suicidality (r = 0.37, p = 0.03).

Discussion

Prior studies have yielded mixed findings as to whether MDD is characterized by reduced mesolimbic activation and/or enhanced dACC activation during anticipation of reward. Moreover, the role of comorbid anxiety disorders on neural responding to reward has rarely been investigated. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to examine whether there were group differences in the neural correlates of reward anticipation among controls, individuals with MDD-only, and individuals with comorbid MDD and PD. Results indicated that there were no group differences in activation of mesolimbic reward regions; however, individuals with MDD-only exhibited greater dACC activation during the anticipation of rewards compared with the healthy controls and the comorbid MDD-PD group (who did not differ from each other).

This pattern of results is consistent with the findings from Knutson et al. (2008) and provides further support for dACC hyperactivity during reward anticipation in those with depression. As was briefly noted, in healthy individuals, the dACC is activated during times of uncertainty, when there is the potential for errors, and during conflict between incompatible information (Botvinick et al., 1999; Carter et al., 1998). Knutson and colleagues (2008) therefore posited that individuals with depression exhibit enhanced dACC activation because they experience more affective conflict during anticipation of monetary gains relative to controls. In other words, because anticipation of rewards is incongruent with depressed mood, the dACC is recruited. Notably, this explanation is supported by additional findings from Knutson et al. (2008) in which those with MDD exhibited dACC hypoactivation, relative to controls, during the anticipation of monetary losses. This suggests that anticipating a loss does not create a conflict for those with depression (at least relative to healthy controls). It is therefore possible that consciously or unconsciously perceiving an impending reward as a conflict diminishes anticipatory pleasure and contributes to the anhedonic responding that is characteristic of depression. Moreover, the findings from this study and Knutson et al. (2008) suggest that individuals with MDD may be able to recognize the imminent possibility of reward and exhibit the primitive reward-related neural response (i.e., activation of mesolimbic regions), but that higher-order cognitive processes may disrupt hedonic anticipation.

It is important to note that comorbid anxiety moderated this effect and there was no difference in dACC activation between comorbid individuals and controls. This is consistent with a few other studies that have found that the comorbid disorder attenuates the typical response of the primary disorder (Weinberg et al., 2012; Kentgen et al., 2000). Given that the current MDD-only and MDD-PD groups were matched on depressive symptoms, these findings suggest that there may be something specific about comorbid PD that interferes with MDD processes. For instance, individuals with PD have repeatedly been shown to be sensitive to uncertain and ambiguous situations (Grillon et al., 2008; Shankman et al., 2013). It is therefore possible that the uncertainty of the outcome/reward may have altered their dACC responding to the task.

Another reason for this finding may be that may be that the presence of PD had independent effect on dACC reactivity, as several studies have found a link between PD and reduced dACC functioning. For instance, damage to the right dACC has been shown to precipitate PD onset (Shinoura et al., 2011), and smaller dACC volumes have been found in PD patients (Asami et al., 2008). It has also been shown that right dACC cerebral blood flow (rCBF) is reduced during spontaneous panic attacks (Fischer et al., 1998), and relative to controls, individuals with PD display reduced bilateral ACC activity while viewing fearful faces (Pillay et al., 2006). Although the mechanisms underlying these findings are still unclear, evidence indicates that the dACC is involved in the expression of fear, which is why damage/abnormalities in this region may cause or maintain PD (Milad and Quirk, 2002; Phelps et al., 2004). In light of these findings, comorbid subjects in the current study may have structural and/or functional dACC abnormalities which impaired conflict detection and processing. Therefore, despite their depressed mood, the comorbid subjects evidenced similar dACC activation as controls during reward anticipation because they were relatively unable to engage in affective conflict monitoring.

It is also possible that the quality of depression, rather than the categorical presence of MDD, is what influences dACC activity. In the current study, individuals with MDD-only reported higher levels of suicidality, including suicidal thoughts and behaviors, than individuals with comorbid MDD-PD. In the literature individuals with comorbid MDD and anxiety often have more severe depressive symptoms, including suicidality, than individuals with MDD-only (Norton et al., 2008), but this was not the case in the current sample. Importantly, self-reported suicidality scores were correlated with dACC activation during the task in the current study. Among individuals with depression, suicidality has been shown to be associated with greater feelings of desperation (Garlow et al., 2008) and hopelessness (Nyer et al., 2013). Prior studies have also shown that there are structural dACC differences in MDD patients who are and are not at risk for suicide (Wagner et al., 2011), and that dACC functioning is associated with treatment-resistant depression (Baeken et al., 2012). Taken together, it is possible that specific subgroups of depressed individuals, namely those with suicidality, evidence abnormal dACC reactivity and experience the greatest affective conflict during reward anticipation due to the fact that the context is starkly incongruent with their hopeless and/or pessimistic mood.

Given that these alternative explanations are somewhat speculative, it is critical that future research: 1) include nuanced measures of mood and depressive symptoms (e.g., indices of pessimism, hopelessness, etc.) to determine whether quality of depression influences neural responses during reward anticipation and 2) include a PD-only group to determine the independent effects PD on dACC during reward processing.

Although these findings address important gaps in the literature, there are several limitations. First, the current sample size was small, particularly the MDD-only group, which reduced statistical power and limited our ability to conduct sub-analyses on individual differences (e.g., gender). These results should therefore be considered preliminary. Second, approximately one-third of the comorbid subjects were currently taking psychiatric mediations and it is possible that this impacted their neural responding. It is important to note, however, that when individuals currently taking medications are excluded from the current study (1 MDD-only and 4 MDD-PD participants excluded), the pattern of results was entirely the same. Third, we did not collect self-reported ratings during the task and it is unclear if there were group differences in positive or negative affect during reward anticipation. Related to this point, the functional relevance of hyperactive dACC reactivity during reward anticipation remains unclear and future work is needed to link these neural effects to functional (e.g., behavioral, affective, cognitive) outcomes.

In sum, the present study indicated that individuals with MDD, without a history of anxiety, displayed greater dACC activation during reward anticipation relative to healthy controls and individuals with MDD and comorbid PD. It is possible that dACC hyperactivity may contribute to reduced reward anticipation in depression; however, the quality of depression and/or the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders may have important impact on neural responding. Given that reduced reward anticipation is a core feature of MDD and is thought to maintain the disorder, it is important that future research continue to investigate the neural processes that characterize these deficits in depressed individuals.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and a National Institute of Mental Health Grant R21 MH080689 (PI: Shankman).

We would like to think E. Jenna Robison, Sarah E Altman, Casey Sarapas, Miranda L. Campbell, and Andrea C Katz for their assistance with the data collection for the present study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors have no conflict of interest related to the present study.

Shankman designed the study and wrote the protocol. Gorka wrote the first draft of the manuscript and conducted the analyses. Huggins and Nelson conducted the literature search and assisted with the analyses. Fitzgerald and Phan assisted with the analyses and interpretation of resultsd. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Alloy LB, Ahrens AH. Depression and pessimism for the future: biased use of statistically relevant information in prediction for self versus others. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987;52:366–378. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asami T, Hayano F, Nakamura M, Yamasue H, Uehara K, Otsuka T, Roppongi T, Nihashi N, Inoue T, Hirayasu Y. Anterior cingulated cortex volume reduction in patients with panic disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeken C, De Raedt R, Bossuyt A. Is treatment-resistance in unipolar melancholic depression characterized by decreased serotonin2A receptors in the dorsal prefrontal-anterior cingulated cortex? Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Fox NA, Benson B, Guyer AE, Williams A, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Pine DS, Ernst M. Neural correlates of reward processing in adolescents with a history of inhibited temperament. Psychol. Sci. 2009;20:1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Clark DA. Anxiety and depression: an information processing perspective. Anxiety Stress Copin. 1988;1:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Parsing reward. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in major depressive disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008;28(4):676–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Nystrom LE, Fissell K, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate cortex. Nature. 1999;402:179–181. doi: 10.1038/46035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll DC, Cohen JD. Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection, and the online monitoring of performance. Neurosurgery. 1998;38:1071–1076. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Shin YC, Jung WH, Jang JH, Kang DH, Choi CH, Choi SW, Lee JY, Hwang JY, Kwon JS. Altered brain activity during reward anticipation in pathological gambling and obsessive-compulsive disorder. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective style and affective disorders: perspectives from affective neuroscience. Cognition Emotion. 1998;12:307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J, Pan H, Kocsis JH, Yang Y, Butler T, Chusid J, Hochberg H, Murrough J, Strohmayer E, Stern E, Silbersweig DA. Lack of ventral striatal response to positive stimuli in depressed versus normal subjects. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:1784–1790. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Andersson JL, Furmark T, Fredrickson M. Brain correlates of an unexpected panic attack: a human positron emission tomographic study. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;24:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00503-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, May JC, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Ryan ND, Carter CS, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Dahl RE. Reward-related decision-making in pediatric major depressive disorder: an fMRI study. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2006;47:1031–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Gard MG, Kring AM, John OP. Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: a scale development study. J. Res. Pers. 2006;40:1086–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Garlow SJ, Rosenberg J, Moore JD, Haas AP, Koestner B, Hendin H, Nemeroff CB. Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depress. Anxiety. 2008;25:482–488. doi: 10.1002/da.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Lissek S, Rabin S, McDowell D, Dvir S, Pine D. Increased anxiety during anticipation of unpredictable but not predictable aversive stimuli as a psychophysiologic marker of panic disorder. Am. J. Psychiat. 2008;165(7):898–904. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Ps. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentgen LM, Tenke CE, Pine DS, Fong R, Klein RG, Bruder GE. Electroencephalographic asymmetries in adolescents with major depression: influence of comorbidity with anxiety disorders. J. Ab. Psychol. 2000;109(4):797. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1996;168:17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Hommer D. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. NeuroReport. 2001;12:3683–3687. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Bhanji JP, Cooney RE, Atlas LY, Gotlib IH. Neural responses to monetary incentives in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lépine JP, Briley M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatric Dis. Treat. 2011;7:3–7. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S19617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M, Cunningham WA. Type I and Type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2009;4:423–428. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Hairston J, Schrier M, Fan J. Common and distinct networks underlying reward valence and processing stages: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011;35:1219–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehl PE. Hedonic capacity: some conjectures. Bull. Menninger Clin. 1975;39:295–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature. 2002;420:70–77. doi: 10.1038/nature01138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998;42:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Temple SR, Pettit JW. Suicidal ideation and anxiety disorders: Elevated risk or artifact of comorbid depression? J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psy. 2008;39(4):515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyer M, Holt DJ, Pedrelli P, Fava M, Ameral V, Cassiello CF, Nock MK, Ross M, Hutchinson D, Farabaugh A. Factors that distinguish college students with depressive symptoms with and without suicidal thoughts. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 2013;25:41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Hughes B, Robertson ER, Cooper JC, Gabrieli JDE. Neural systems supporting the control of affective and cognitive conflicts. J. Cognitive Neurosci. 2009;21:1841–1854. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, Delgado MR, Nearing KI, LeDoux JE. Extinction learning in humans: role of the amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron. 2004;43:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay SS, Gruber SA, Rogowska J, Simpson N, Yurgelun-Todd DA. fMRI of fearful facial affect recognition in panic disorder: the cingulate gyrus-amygdala connection. J. Affect. Disord. 2006;94:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Holmes AJ, Dillon DG, Goetz EL, Birk JL, Bogdan R, Dougherty DD, Iosifescu DV, Rauch SL, Fava M. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009a;166:702–710. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Iosifescu D, Hallett LA, Ratner KG, Fava M. Reduced hedonic capacity in major depressive disorder: evidence from a probabilistic reward task. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009b;43:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, Saloman TV, Slagter HA, Fox AS, Winter JJ, Davidson RJ. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12:154–167. doi: 10.1038/nrn2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman SA, Nelson BD, Sarapas C, Robison-Andrew EJ, Campbell ML, Altman SE, McGowan SK, Katz AC, Gorka SM. A psychophysiological investigation of threat and reward sensitivity in individuals with panic disorder and/or major depressive disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013;122:322–338. doi: 10.1037/a0030747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherdell L, Waugh CE, Gotlib IH. Anticipatory pleasure predicts motivation for reward in major depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2012;121:51–60. doi: 10.1037/a0024945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoura N, Yamada R, Tabei Y, Otani R, Itoi C, Saito S, Midorikawa A. Damage to the right dorsal anterior cingulate cortex induces panic disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;11:569–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoski MJ, Felder J, Bizzell J, Green SR, Ernst M, Lynch TR, Dichter GS. fMRI of alterations in reward selection, anticipation, and feedback in major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2009;118:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoski MJ, Rittenberg A, Dichter GS. Major depressive disorder is characterized by greater reward network activation to monetary than pleasant image rewards. Psychiat. Res.-Neuroim. 2011;194(3):263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobin C, Sackeim HA. Psychomotor symptoms of depression. Am. J. Psychiat. 154:4–17. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Schwartzman AN, Lambert WE, Zald DH. Worth the 'EEfRT'? The efforts expenditure for rewards task as an objective measure of motivation and anhedonia. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurugizawa T, Uematsu A, Uneyama H, Torii K. Functional brain mapping of conscious rats during reward anticipation. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2012;206:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker J, Dillon DG, Pizzagalli DA. The role of the nucleus accumbens and rostral anterior cingulate cortex in anhedonia: integration of resting EEG, fMRI, and volumetric techniques. Neuroimage. 2009;45:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G, Koch K, Schachtzabel C, Schultz CC, Sauer H, Schlösser RG. Structural brain alterations in patients with major depressive disorder and high risk for suicide: evidence for a distinct neurobiological entity? Neuroimage. 2011;54:1607–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Simms LJ, Kotov R, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, Gamez W, Stuart S. Development and validation of the inventory of depression and anxiety symptoms (IDAS) Psychol. Assessment. 2007;19:253–268. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Increased error-related brain activity distinguishes generalized anxiety disorder with and without comorbid major depressive disorder. J. Ab. Psychol. 2012;121(4):885. doi: 10.1037/a0028270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]