Abstract

Ethanol increased the frequency of miniature glycinergic currents [miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs)] in cultured spinal neurons. This effect was dependent on intracellular calcium augmentation, since preincubation with BAPTA (an intracellular calcium chelator) or thapsigargin [a sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump inhibitor] significantly attenuated this effect. Similarly, U73122 (a phospholipase C inhibitor) or 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate [2-APB, an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor (IP3R) inhibitor] reduced this effect. Block of ethanol action was also achieved after preincubation with Rp-cAMPS, inhibitor of the adenylate cyclase (AC)/PKA signaling pathway. These data suggest that there is a convergence at the level of IP3R that accounts for presynaptic ethanol effects. At the postsynaptic level, ethanol increased the decay time constant of mIPSCs in a group of neurons (30 ± 10% above control, n = 13/26 cells). On the other hand, the currents activated by exogenously applied glycine were consistently potentiated (55 ± 10% above control, n = 11/12 cells), which suggests that ethanol modulates synaptic and nonsynaptic glycine receptors (GlyRs) in a different fashion. Supporting the role of G protein modulation on ethanol responses, we found that a nonhydrolyzable GTP analog [guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS)] increased the decay time constant in ∼50% of the neurons (28 ± 12%, n = 11/19 cells) but potentiated the glycine-activated Cl− current in most of the neurons examined (83 ± 29%, n = 7/9 cells). In addition, confocal microscopy showed that α1-containing GlyRs colocalized with Gβ and Piccolo (a presynaptic cytomatrix protein) in ∼40% of synaptic receptor clusters, suggesting that colocalization of Gβγ and GlyRs might account for the difference in ethanol sensitivity at the postsynaptic level.

Keywords: glycinergic miniature IPSCs, strychnine, spinal neurons, ethanol, forskolin, adenylate cyclase, calcium

in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), rapid inhibitory neurotransmission is mediated by ionotropic glycine (GlyR) and GABAA (GABAAR) receptors. GlyR activation leads to an increase in Cl− conductance in response to glycine, mainly in spinal cord and brain stem neurons. Interestingly, GlyRs are allosterically modulated by Zn2+, neurosteroids, endocannabinoids, general anesthetics, and clinically relevant concentrations of ethanol (Yevenes and Zeilhofer 2011).

There is abundant evidence suggesting that modulation of inhibitory glycinergic neurotransmission by ethanol is associated with the behavioral responses observed during ethanol intoxication (Perkins et al. 2010; Spanagel 2009). For instance, basic functions such as motor coordination, respiratory rhythms, and pain transmission, which are under significant control of glycinergic transmission, are extensively altered by ethanol. However, despite the relevance of glycinergic currents in the inhibitory effects of ethanol in the CNS, the molecular mechanism involved in this modulation has not yet been entirely elucidated.

To date, five different GlyR subunits (α1–4 and β) have been described. These subunits arrange themselves around a central pore permeable to Cl− whose opening leads to membrane hyperpolarization. The resulting receptors can be conformed as homopentamers (α1- to α4-subunits) or heteropentamers (coexpressed with β-subunits). Each subunit is composed of four transmembrane domains (TM1–4), an extracellular NH2-terminal domain and a large intracellular loop (IL) between TM3 and 4 (Lynch 2004). The IL has been implicated in sorting and anchoring of GlyRs to postsynaptic densities (Meyer et al. 1995). Furthermore, it has been shown that glycinergic currents are modulated by phosphorylation (Gu and Huang 1998) and Gβγ allosteric regulation (Yevenes et al. 2003).

It is accepted that ethanol actions on postsynaptic GlyRs involve extracellular and transmembrane residues that are critical for the conductance and gating of the GlyR channel (Borghese et al. 2012; Mihic et al. 1997; Perkins et al. 2008). Moreover, increasing evidence shows that the effects of clinically relevant concentrations of ethanol on GlyRs are affected by the state of G protein activation (Yevenes et al. 2008, 2010). The functional consequence of this effect is in part explained by conformational changes that favor the interaction of GlyRs with the agonist; thus ethanol increases the apparent affinity for glycine without changing the efficacy of the receptor (Aguayo et al. 1996; Eggers and Berger 2004; Ye et al. 2001).

On the other hand, little is known about the mechanism by which ethanol might affect the presynaptic site. Therefore, we studied the pre- and postsynaptic effects of ethanol on glycinergic synapses in spinal neurons. At the presynaptic level, ethanol increased the release of glycine by intracellular calcium and PKA pathways. The postsynaptic responses appeared to be associated with the presence of colocalization of Gβ and GlyR.

METHODS

Spinal cord neuron cultures.

Spinal cord neurons obtained from five or six C57BL/6J mouse embryos (E13–14 days) were plated at 250,000 cells/ml onto 18-mm glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (70–150 kDa; Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) in plating medium for 24 h, and then the medium was replaced with feeding medium every 5 days. The neuronal feeding medium consisted of 90% minimal essential medium (MEM; GIBCO, Rockville, MD), 5% heat-inactivated horse serum (Hyclone), 5% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), and a mixture of nutrient supplements (Aguayo and Pancetti 1994). Care of animals and the experimental protocols of this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Use Committee of the University of Concepción and conducted according to the ethical protocols established by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Electrophysiology.

Recordings of isolated spinal cord neurons were performed with the patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981). Glycine-activated currents and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were studied in spinal neurons with the whole cell configuration. Patch pipettes, with a 4- to 6-MΩ resistance, were prepared from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments) with a P-87 micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument). After a whole cell configuration was established, cell capacitance and series resistance were compensated by >85% with the internal circuitry of the Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Recordings of glycine currents were done at a holding potential of −60 mV. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 120 CsCl, 4.0 MgCl2, 10 BAPTA, 0.5 Na2-GTP, and 2.0 Na2-ATP (pH 7.4, 290–310 mosM), and the external solution contained (in mM) 150 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4, 300–330 mosM). Currents were displayed and stored on a personal computer with a 1200A Digidata. Capacitance and access resistances were monitored continuously throughout the recordings, and a change of ≥10% was sufficient to exclude the recording from analysis.

Solution preparation and delivery system.

Stock solutions were prepared in distilled water or DMSO (0.1% vol/vol) and stored at −20°C. The working concentrations and drugs used were (in μM) 0.1 tetrodotoxin (TTX; Sigma), 4 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; Sigma), 5 gabazine (Tocris), 1 strychnine (Tocris), 10 U73122 (Tocris), 10 Rp-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic hydrogen phosphorothioate triethylammonium salt hydrate (Rp-cAMPS; Sigma), 10 forskolin (Sigma), 100 BAPTA-AM (Sigma), 500 EGTA (Sigma), and 500 guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS; Sigma). Working concentrations of ethanol (Merck) were prepared by directly diluting the stock in the external solution. To apply different solutions, we used a mobile series of pipettes (∼200 μm in diameter) placed within 50 μm of the cell and connected to a 20-ml reservoir. These pipettes were mounted on a micromanipulator, and a small displacement was made for a complete exchange of external solution bathing the cell under study.

Glycinergic mIPSCs and glycine-evoked currents.

We examined the properties of two types of glycinergic currents: 1) pharmacologically isolated glycinergic mIPSCs, which are related to the spontaneous release of single vesicles at the synaptic level, and 2) the glycine-activated currents that account for synaptic and nonsynaptic GlyR activation. The cells were washed with ligand-free solution during the interstimulation interval. Despite the fact that potentiation of glycinergic currents is observed with 10 mM of ethanol (Aguayo and Pancetti 1994), we evaluated the effects of 100 mM to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, facilitating statistical analysis and comparison with previous studies from our and other laboratories. To isolate glycinergic currents in spinal neurons, the recordings were done as previously reported (van Zundert et al. 2004) in the presence of gabazine (5 μM) to block GABAergic transmission, CNQX (4 μM) to block AMPAergic transmission, and TTX to block sodium channels (0.1 μM). The remaining mIPSCs were reversibly blocked by strychnine (1 μM), demonstrating their glycinergic nature. GABAergic mIPSCs and AMPAergic miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) were isolated with similar types of pharmacological protocols. Experiments for the evaluation of ethanol on presynaptic calcium stores were made as follows: Spinal neurons [15 days in vitro (DIV)] were incubated for at least 30 min with a high-potassium external solution (in mM: 125 NaCl, 30 KCl, 3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES; pH 7.4, 300–330 mosM) containing these inhibitors: 1 μM thapsigargin (Alomone Labs), 100 μM ryanodine (Alomone Labs), and 14 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB; Sigma-Aldrich). Recordings of isolated glycinergic mIPSCs were done in the presence or absence of ethanol (100 mM).

Immunocytochemistry.

Glass coverslips with cells were incubated with GlyR-α1 (1:50, mouse; SySys) primary antibody in neuronal feeding medium for 10 min (37°C). After 3 washes with 1× PBS, neurons were fixed for 10 min with cold methanol (−20°C). After removal of methanol by 1× PBS washes, the neurons were incubated with a combination of Gβ (1:200, rabbit; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Piccolo (1:200, guinea pig; SySys) primary antibodies or Microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP1B, 1:300, guinea pig; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Subsequently, the neurons were blocked with normal horse serum (10%) for 30 min. Epitope visualization was performed by incubation of secondary antibodies DyLight 488 donkey anti-mouse, DyLight 649 donkey anti-rabbit, and Cy3 donkey anti-guinea pig IgG (1:200; Jackson Immunoresearch), respectively. After five washes with 1× PBS, the coverslips were placed on microscope slides with Dako mounting medium (DakoCytomation) for subsequent analysis by confocal microscopy. The controls were performed by omission of primary antibodies, by using only the secondary antibody, or by using a single immunostaining to corroborate that the signal was similar to the triple immunostaining. Areas with immunostained spinal neurons were randomly chosen for imaging by confocal microscopy (confocal spectral LSM780 Zeiss, ×63 oil immersion objective, NA 1.35, CMA Bio Bio). Color immunofluorescent colocalization analysis was studied by superimposing the DyLight 488 signal with DyLight 649 and Cy3 with the ImageJ program (NIH). Laplace filters in combination with automatic intensity threshold values selected in I′[x,y] of Piccolo, a presynaptic cytomatrix-associated protein (Cases-Langhoff et al. 1996), immunoreactivity were utilized for the segmentation of the synaptic compartment across the images. Segmentation methods were constant in all quantified images. The area within these selected regions of interest, representing the synaptic compartment, were used to carry out the colocalization analysis between GlyR and Gβ, utilizing Manders colocalization coefficients for the real images and for the randomized image (Costes et al. 2004).

Data analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with paired t-test (with and without ethanol), ANOVA, and Dunnett's post hoc test, and values are expressed as means ± SE; values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism 6 and Origin 8.0 (MicroCal) software programs were used for statistical analysis and data plots. The synaptic recordings were analyzed with Mini Analysis 6.0.3 (Synaptosoft).

RESULTS

Ethanol increased glycinergic mIPSC frequency in C57BL/6J spinal cord neurons.

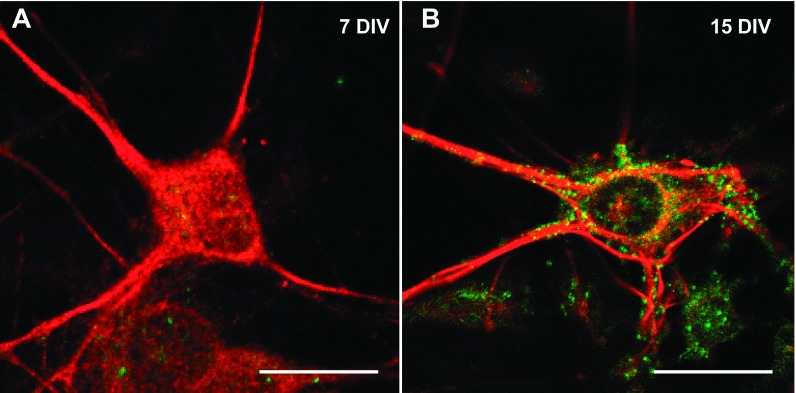

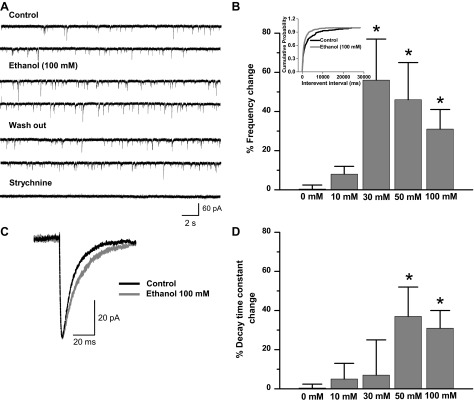

In this study, we analyzed the effects of ethanol on glycinergic mIPSCs in mature C57BL/6J spinal cord neurons (15 DIV). Spinal cord neurons initiate the synaptogenesis process after 5 DIV, but the mature synapse, as determined by physiological and pharmacological properties, was found at 15 DIV (van Zundert et al. 2004). The present results demonstrated that α1-GlyR clusters were localized in the soma and primary processes of mature but not immature neurons (Fig. 1). This is relevant because it was previously described that α1-GlyRs, but not α2, have the molecular determinants necessary for ethanol potentiation (Yevenes et al. 2010). Although we cannot discard the presence of some α2, previous studies using RT-PCR showed that 15 DIV spinal neurons in culture expressed predominantly the α1-GlyR subunit at this stage (van Zundert et al. 2004). Thus we examined the ethanol sensitivity in 15 DIV neurons with whole cell voltage-clamp recordings. Representative traces of glycinergic mIPSCs in the presence and absence of 100 mM of ethanol are shown in Fig. 2A. The frequency of mIPSCs in spinal neurons increased significantly after acute incubation with 30 mM (56 ± 21%, n = 6), 50 mM (46 ± 9%, n = 9), and 100 mM (31 ± 10%, n = 26) but not 10 mM (8 ± 4%, n = 6) ethanol compared with the control (0 mM ethanol) [Fig. 2B, F (4,65) = 4.077, P = 0.005]. The data also showed that the cumulative probability curve for the interevent interval shifted to the left (Fig. 2B, inset; P < 0.0001, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), supporting the idea that ethanol increases mIPSC spontaneous glycine release at spinal synapses. On the other hand, the enhancing effects of ethanol on glycinergic transmission were not detected in GABAergic (−14 ± 12% of control, paired Student's t-test, P = 0.388, n = 5) or AMPAergic (−19 ± 8%, paired Student's t-test, P = 0.186, n = 6) miniature currents.

Fig. 1.

Expression of glycine receptor (GlyR) clusters in C57BL/6J spinal neurons. Confocal microphotographs obtained in spinal cord neurons show immunoreactivity for GlyR α1-subunit (green) and Microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP1B, red). A: immature neurons at 7 days in vitro of development (7 DIV) lack this subunit. B: expression of α1-GlyR clusters in mature neurons (15 DIV). Scale bars, 15 μm.

Fig. 2.

Ethanol increases the frequency and decay time constant of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) in a concentration-dependent manner. A: traces of isolated glycinergic currents (4 μM CNQX, 5 μM gabazine, 0.1 μM TTX) of mature neurons in the presence of 100 mM ethanol. Blockade by strychnine (1 μM) demonstrates the glycinergic nature of these currents. B: % frequency change obtained in the presence of different concentrations of ethanol compared with control (0 mM ethanol) (*P < 0.05, 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test). Inset: cumulative probability of interevent interval shows that 100 mM ethanol shifts the distribution curve to the left (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, *P < 0.0001). C: representative averaged current in the presence and absence of ethanol. D: % decay time constant change in response to different concentrations of ethanol (*P < 0.05, 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test). Synaptic currents were recorded in whole cell configuration at 20–22°C and −60 mV.

In addition, ethanol also reversibly increased the decay time constant of mIPSCs. Figure 2C shows representative averaged glycinergic synaptic current in control and ethanol conditions. The data show that ethanol increased the decay time constant after incubation with 50 mM (37 ± 14%, n = 9) and 100 mM (32 ± 8%, n = 26) [Fig. 2D; F(4,68) = 3.347, P = 0.015] without changing the amplitude or rise time constant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of ethanol on mIPSC parameters

| Frequency, Hz | Decay, ms | Amplitude, pA | Rise Time, ms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 13 ± 1 | 17 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| Ethanol | 0.9 ± 0.1* | 17 ± 1* | 18 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

Values are mean ± SE (n = 26 neurons) miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current (mIPSC) parameters in spinal cord neurons in the presence and absence (control) of 100 mM ethanol: frequency (*P = 0.013), decay time constant (*P = 0.036), amplitude (P = 0.554), and rise time (P = 0.106).

Effect of ethanol on mIPSC frequency involves a calcium signaling pathway.

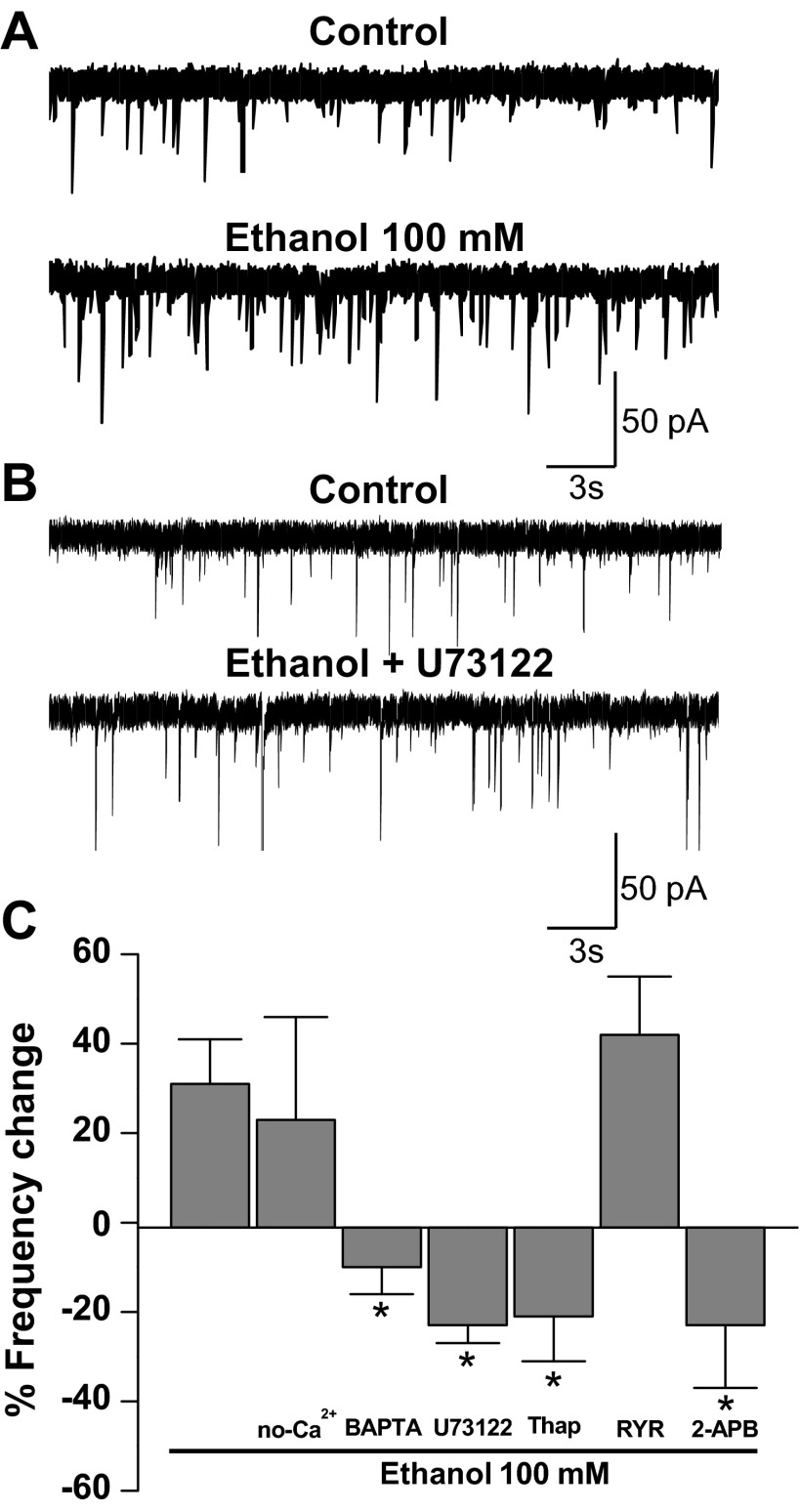

Because previous studies showed a role of calcium signaling in the presynaptic effects of ethanol on GABAergic synapses (Kelm et al. 2007), we wanted to determine whether this signaling pathway was important for the enhancement of glycine neurotransmission at spinal synapses. Considering that phospholipase C (PLC) activation induces the release of calcium from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (IP3Rs) at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Berridge 2009; Streb et al. 1983), we studied the participation of PLC and calcium in this presynaptic effect of ethanol. As previously shown, ethanol increased the frequency of glycinergic mIPSCs (Fig. 3A) and incubation with the PLC inhibitor U73122 prevented ethanol from exerting this effect (Fig. 3B). The data in Fig. 3C show the strong inhibitory effect of U73122 on the increase of mIPSCs in presence of ethanol [−23 ± 4% from control, n = 11; F(6,64) = 5.024, P = 0.0002]. It is known that IP3 generated by PLC activates IP3Rs, increasing the calcium release from the ER. The inhibition of IP3Rs by 14 μM 2-APB blocked the increase of mIPSCs frequency [−22 ± 14% from control, n = 5; F(6,64) = 5.024, P = 0.022]. Conversely, no changes were found after incubation with ryanodine, suggesting that calcium mobilization was not dependent on activation of ryanodine receptors (30 ± 6%, n = 4). In addition, inhibition of the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump by thapsigargin eliminated the increase of mIPSC frequency [−21 ± 10%, n = 11; F(6,64) = 5.024, P = 0.003; Fig. 3C]. Additionally, when the effect of ethanol was studied in neurons bathed in a nominally calcium-free extracellular solution (no-Ca2+ condition; Fig. 3C), we did not find any difference compared with control conditions (24 ± 23%, n = 6), suggesting that if calcium was important it was not derived from an external source. On the other hand, when the recordings were done in the presence of BAPTA-AM, we found that the effect of ethanol on mIPSC frequency was blocked [−13 ± 6%, n = 8; F(6,64) = 5.024, P = 0.0003; Fig. 3C], suggesting that ethanol caused an increase in glycine release by presynaptic intracellular calcium signaling activation.

Fig. 3.

The effect of ethanol on mIPSC frequency involves calcium signaling pathways. A: current traces of glycinergic mIPSCs in the presence and absence (control) of 100 mM ethanol. B: traces of glycinergic mIPSCs in the presence of a PLC inhibitor (U73122, control) and 100 mM ethanol + U73122. C: % change of mIPSC frequency in the presence of 100 mM ethanol (control), external solution without calcium (no-Ca2+), BAPTA-AM (100 μM), U73122 (10 μM), thapsigargin (Thap, 1 μM), ryanodine (RYR, 100 μM) and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB, 14 μM) (*P < 0.05, 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test).

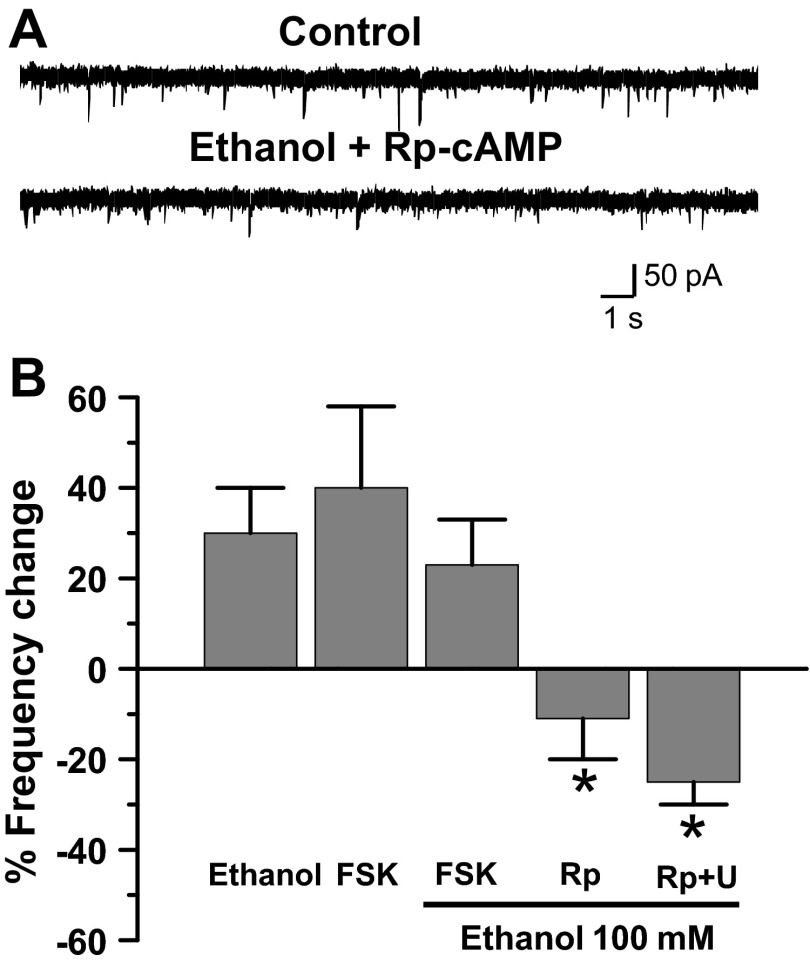

Inhibition of adenylate cyclase reduced effect of ethanol on mIPSC frequency.

Previous research has linked Gs-coupled G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) ethanol activation with enhanced GlyRs modulation (Yevenes et al. 2011). To examine whether the increase in mIPSC frequency was also dependent on this pathway, we incubated spinal neurons with the cAMP analog Rp-cAMPS and found that the effects of ethanol were inhibited [Fig. 4; −11 ± 8%, n = 8; F(4,47) = 3.278, P = 0.039]. In other experiments, we observed that forskolin (10 μM), an adenylate cyclase (AC) activator (Pinto et al. 2008), caused an increase in mIPSC frequency to an extent similar to that seen in the presence of ethanol (40 ± 18%, n = 6; Fig. 4B). However, when forskolin and ethanol were coincubated, no additional increase in frequency was found (n = 6; Fig. 4B), indicating an occlusion of these signaling pathways. These data demonstrated that the AC/PKA pathway plays a key role in the signaling related to the presynaptic response to ethanol. In addition, we showed that ethanol actions were largely attenuated by simultaneous inhibition of cAMP/PKA and PLC pathways by Rp-cAMPS and U73122 [Fig. 4B;−27 ± 8%, n = 4; F(4,47) = 3.278, P = 0.036], suggesting that there is some convergence at the level of the IP3R.

Fig. 4.

Adenylate cyclase plays a role in ethanol mIPSC frequency increase. A: data show that Rp-cAMPS blocked the effects of ethanol on mIPSC frequency. B: % change of mIPSC frequency in the presence of 100 mM ethanol (control), forskolin (FSK, 10 μM), FSK + ethanol, Rp-cAMPS (Rp, 10 μM) + ethanol, and Rp (10 μM) + U73122 (U, 10 μM) + ethanol, (*P < 0.05, 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test).

Effects of ethanol at postsynaptic GlyRs.

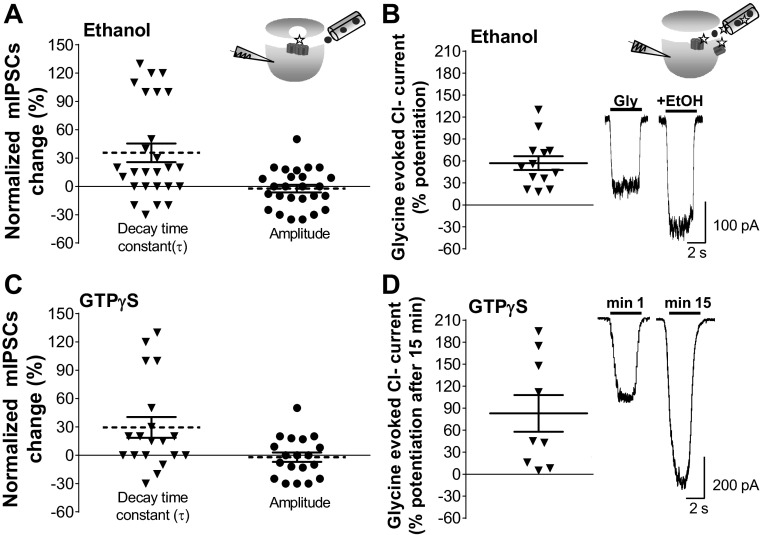

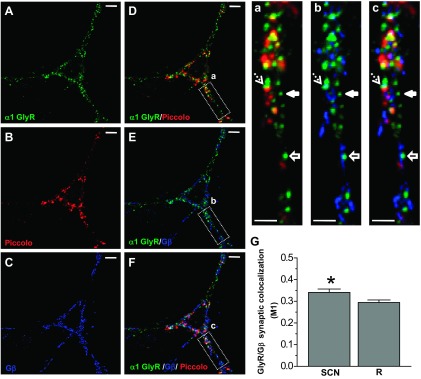

Acute exposure to ethanol (100 mM) increased the decay time constant of glycinergic mIPSCs in half of the cells recorded (n = 13/26) (Fig. 5A), without changes in amplitude (Table 1). The effects of ethanol on decay time constant and frequency were unrelated, because only a few neurons were affected pre- and postsynaptically by ethanol (3 of 13 cells). This is in agreement with the notion that while changes in frequency reflect presynaptic mechanisms the increase of decay is related to postsynaptic ion channel properties (van Zundert et al. 2004). Interestingly, glycine-activated Cl− currents in the same neurons (EC10–20 = 15 μM) were consistently potentiated (55% ± 10% of control, paired Student's t-test, P < 0.0001, n = 12; Fig. 5B), which suggests that ethanol modulated the synaptic and nonsynaptic GlyRs in a different fashion. Previous studies showed that the TM3–4 IL and Gβγ signaling play a role in the potentiation of α1-containing GlyRs by ethanol (Yevenes et al. 2008; Zhu and Ye 2005). Therefore, we wanted to see whether the state of G protein activation by Gβγ could influence glycinergic mIPSC parameters. For this, we evaluated the effects of GTPγS (500 μM) on synaptic parameters and glycine-activated currents after 15 min of intracellular dialysis of the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog and found that GTPγS increased the decay time constant (28 ± 12%, n = 19). Similar to data obtained in response to ethanol, 58% (n = 11/19) of cells were potentiated, without changes in the amplitude of the mIPSCs (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the amplitude of the glycine-activated Cl− current was consistently enhanced after intracellular dialysis of GTPγS (83 ± 29% of control, paired Student's t-test, P < 0.033, n = 9; Fig. 5D). The previous data show that while nonsynaptic receptors were consistently modulated by ethanol and GTPγS, only half of the synaptic currents were potentiated. Thus it is possible that some synaptic GlyRs are not linked to G proteins, explaining the insensitivity. Therefore, we examined the immunocytochemical colocalization of GlyRs, Piccolo, and Gβ in an attempt to understand the differential actions of G protein on GlyRs. The signal with the presynaptic protein Piccolo was used to determine synaptic and nonsynaptic GlyR cluster localization (Fig. 6). Colocalization analysis showed that ∼40% of the GlyR signal colocalized with Gβ at the synaptic level (Fig. 6G), suggesting that these molecular complexes are those susceptible to modulation by ethanol and GTPγS.

Fig. 5.

Differential effects of ethanol and guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) on Cl− currents activated by synaptic and exogenous glycine. A: effects of ethanol on the decay time constant and amplitude of mIPSCs, where each neuron was its own control (inverted triangles and filled circles show % change on each individual neuron; n = 26). Means ± SE are indicated by the segmented lines. Inset: protocol for mIPSC recordings. Ethanol solution was applied by switching from a pipette containing normal external solution to one with ethanol (circles). Here, glycine (star) is released from presynaptic vesicles and interacts with postsynaptic GlyRs. B: potentiation of glycine-evoked current (EC10–20 of glycine) in the presence of ethanol (100 mM) compared with the control (*P < 0.0001, paired Student's t-test, n = 12). Top inset: protocol for glycine-elicited current recording. Glycine and ethanol solution were applied by switching from a pipette containing normal external solution to one with glycine (stars) plus ethanol (circles), resulting in the activation of both synaptic and nonsynaptic GlyRs. Bottom inset: traces of glycine-activated currents in the presence of 100 mM ethanol (+EtOH) compared with the control (Gly). C: % mIPSC change obtained after 15 min of intracellular dialysis of GTPγS. Each cell is its own control (n = 19). Means ± SE are indicated by the segmented lines. D: % potentiation of glycine-elicited currents in the presence of GTPγS (500 μM) at minute 15 compared with the control (EC10–20 of glycine) at minute 1 (*P = 0.033, paired Student's t-test, n = 9 neurons). Inset: representative traces of glycine-activated current at minutes 1 and 15 of intracellular dialysis of GTPγS.

Fig. 6.

Colocalization of α1 GlyR with Piccolo and Gβ. A–C: confocal microphotographs obtained in 15 DIV spinal neurons show immunoreactivity for α1 GlyR (green), the presynaptic protein Piccolo (red), and Gβ (blue). D–F: merged signals show the colocalization. Scale bars, 10 μm. a–c: Confocal zooms show the diverse types of GlyR clusters: colocalized with Gβ (dashed arrows), a nonsynaptic cluster (solid arrows), and a nonsynaptic cluster colocalized with Gβ (solid arrows with line). Scale bars, 3 μm. G: quantification of the degree of colocalization. Manders colocalization coefficient (M1) shows synaptic GlyRs that colocalized with Gβ. This was calculated for the actual data (SCN) and the respective randomized images (R). Bars correspond to means ± SE of 9 individual neurons (*P < 0.05, paired Student's t-test, n = 9).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies in different cell types have shown that clinically relevant concentrations of ethanol (1–100 mM) can affect the glycine-activated Cl− current in native and recombinant receptors (Aguayo et al. 1996; Crawford et al. 2007; Mihic et al. 1997; Perkins et al. 2008). In addition, ethanol studies at the synaptic level revealed that glycinergic currents were also altered. For example, high ethanol (100–200 mM) increased the frequency of glycinergic mIPSCs in developing hypoglossal and newborn spinal neurons (Eggers et al. 2000; Ziskind-Conhaim et al. 2003). The effects of ethanol on the decay time constant and amplitude of postsynaptic GlyRs in brain stem, ventral tegmental area, and spinal neurons were less ubiquitous, with increases and decreases in receptor function (Eggers and Berger 2004; Ye et al. 2001). Using spinal cord neurons expressing primarily mature α1-containing synapses (Tapia and Aguayo 1998), we have reexamined the effects of a range of clinically relevant concentrations of ethanol (10–100 mM) and evaluated the mechanisms for the pre- and postsynaptic actions of this drug of abuse.

Presynaptic ethanol effects.

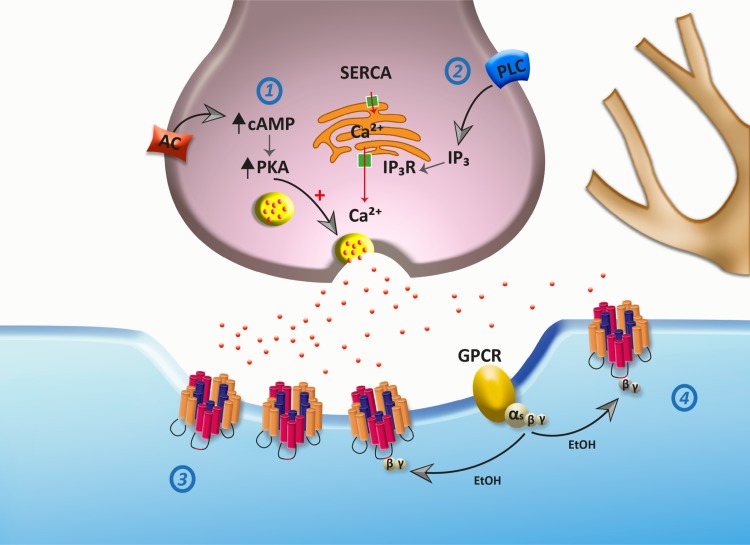

Studies on the mechanism of ethanol actions at glycinergic synapses have mainly focused on postsynaptic mechanisms, leaving the presynaptic actions largely unidentified. The release of neurotransmitters is primarily controlled by calcium signaling and by cAMP-mediated PKA phosphorylation pathways (Choi et al. 2009; Trudeau et al. 1998). In addition, it seems that there exists a cross talk pathway between cAMP/PKA and Ca2+ signaling (Tang et al. 2003). In the present study, we found that ethanol, starting at 30 mM, reversibly increased the frequency of glycinergic neurotransmission. This enhancement in frequency was mainly due to intracellular calcium derived from the ER, since we found that preincubation of the neurons with BAPTA, thapsigargin, and 2-APB strongly blocked the presynaptic effect of ethanol. Therefore, we postulate that the activation of the PLC/IP3R/Ca2+ signaling pathway promotes glycine release in response to ethanol. Interestingly, previous studies showed that ethanol can affect the release of intracellular calcium from the ER, affecting IP3R (Kelm et al. 2010). Additionally, the effect of ethanol was also blocked by Rp-cAMPS and was occluded by previous application of forskolin, an AC activator (Pinto et al. 2008). Therefore, ethanol can increase the inhibitory tone in spinal neurons by increasing synaptic glycine availability (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the existence of a cAMP-PKA-IP3R-calcium link might play a key role in the spatial-temporal shape of vesicular release in the presence of ethanol. The finding that inhibitors of both cAMP/PKA and PLC pathways largely attenuated the presynaptic action of ethanol might suggest that there is an important convergence at the level of IP3R. This possibility is in agreement with a previous study that showed that IP3R is phosphorylated by PKA, leading to functional changes (DeSouza et al. 2002). Additionally, we believe that the lack of effects of extracellular calcium on the increase of glycinergic transmission provides evidence to exclude the role of presynaptic GlyRs, since they act by increasing Ca2+ influx and glutamatergic transmission (Choi et al. 2013). The differential effects of IP3Rs on glycine and GABAA neurotransmissions suggest the existence of macromolecular complex specificity, as previously shown (DeSouza et al. 2002).

Fig. 7.

Scheme of proposed ethanol effects on glycinergic synapses. At the presynaptic level, ethanol increases vesicular glycine release (red dots) by activation of adenylate cyclase (AC)/PKA (1) and PLC/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor (IP3R)/Ca2+ (2) pathways. Here, AC activation can increase PKA activity, leading to vesicular release. The data also support the idea that ethanol increases intracellular calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by IP3R activation. At the postsynaptic level, GlyRs are located at synaptic (3) and nonsynaptic (4) sites. Modulation of GlyRs by Gβγ protein plays a key role in ethanol effects.

Postsynaptic effects of ethanol.

Mature GlyRs are localized at postsynaptic sites in clusters composed of different combinations of α- and β-subunits (Grudzinska et al. 2005). It has been previously described that α1-subunit expression in spinal neurons is high at 15 DIV (Malosio et al. 1991). On the other hand, α1-subunits have the molecular requirements necessary for ethanol sensitivity (Yevenes et al. 2010). Therefore, the predominance of α1-subunits in the synaptic clusters of responsive cells can account for the increase in decay time constant in the presence of ethanol.

One of the proposed mechanisms of ethanol action on GlyRs involves G protein activation (Yevenes et al. 2008). More recent studies showed that intracellular incubation with the RQHc7 peptide, which blocked the interaction of Gβγ proteins with the α1-GlyR intracellular loop, reduced the effects of ethanol on the decay time constant of mIPSCs (San Martin et al. 2012). Our data revealed that postsynaptic GlyRs were affected to different degrees by ethanol. For example, ethanol potentiated the glycine-evoked current in most of the tested neurons, but only 50% of mIPSC glycinergic currents were affected by ethanol (Fig. 5). Interestingly, similar results were observed after intracellular dialysis of GTPγS to activate G proteins, i.e., the glycine-evoked Cl− current was consistently potentiated (Yevenes et al. 2003; Zhu and Ye 2005), while only 58% of the neurons showed positive actions on mIPSCs. Although other possibilities exist, the data suggest that the ethanol-insensitive synaptic GlyRs might be those that are not coupled to Gβ protein activation. In agreement with this idea, confocal microscopy analysis of synaptic GlyR and Gβ showed 40% colocalization, supporting the idea that synaptic ethanol-sensitive differences are related to a differential state of G protein modulation (Fig. 6), and future studies should elucidate the functional consequence of this modulation and the potential link to complex behavioral ethanol responses.

Several ethanol-related phenotypes in animal models reproduce different aspects of the complex effects of ethanol; one of these phenotypes is ethanol preference, which is a predictor of risk for alcohol abuse (Crabbe et al. 1994). Interestingly, the C57BL/6J inbred strain has a higher innate ethanol preference, and this might have a neurobiological correlation (Chesler et al. 2012; Messiha 1985). Future studies should address whether this difference in GlyR sensitivity is related to the behavioral difference.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA-17875 and MECESUP UCH 0704 student fellowship from the University of Chile.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.A.M. and E.J.F.-P. conception and design of research; T.A.M., A.A., B.M., L.S.M., C.C., and P.M. performed experiments; T.A.M., A.A., B.M., L.S.M., C.C., and P.M. analyzed data; T.A.M., E.J.F.-P., and A.S. interpreted results of experiments; T.A.M., E.J.F.-P., and A.S. prepared figures; T.A.M. drafted manuscript; T.A.M., G.E.H., and L.G.A. edited and revised manuscript; G.E.H. and L.G.A. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lauren J. Aguayo for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Aguayo LG, Pancetti FC. Ethanol Modulation of the γ-aminobutyric acidA- and glycine-activated Cl− current in cultured mouse neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 270: 61–69, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo LG, Tapia JC, Pancetti FC. Potentiation of the glycine-activated Cl− current by ethanol in cultured mouse spinal neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 279: 1116–1122, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 933–940, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghese CM, Blednov YA, Quan Y, Iyer SV, Xiong W, Mihic SJ, Zhang L, Lovinger DM, Trudell JR, Homanics GE, Harris RA. Characterization of two mutations, M287L and Q266I, in the alpha1 glycine receptor subunit that modify sensitivity to alcohols. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340: 304–316, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases-Langhoff C, Voss B, Garner AM, Appeltauer U, Takei K, Kindler S, Veh RW, De Camilli P, Gundelfinger ED, Garner CC. Piccolo, a novel 420 kDa protein associated with the presynaptic cytomatrix. Eur J Cell Biol 69: 214–223, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler EJ, Plitt A, Fisher D, Hurd B, Lederle L, Bubier JA, Kiselycznyk C, Holmes A. Quantitative trait loci for sensitivity to ethanol intoxication in a C57BL/6Jx129S1/SvImJ inbred mouse cross. Mamm Genome 23: 305–321, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IS, Nakamura M, Cho JH, Park HM, Kim SJ, Kim J, Lee JJ, Choi BJ, Jang IS. Cyclic AMP-mediated long-term facilitation of glycinergic transmission in developing spinal dorsal horn neurons. J Neurochem 110: 1695–1706, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Nakamura M, Jang IS. Presynaptic glycine receptors increase GABAergic neurotransmission in rat periaqueductal gray neurons. Neural Plast 2013: 954302, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costes SV, Daelemans D, Cho EH, Dobbin Z, Pavlakis G, Lockett S. Automatic and quantitative measurement of protein-protein colocalization in live cells. Biophys J 86: 3993–4003, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Belknap JK, Buck KJ. Genetic animal models of alcohol and drug abuse. Science 264: 1715–1723, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford DK, Trudell JR, Bertaccini EJ, Li K, Davies DL, Alkana RL. Evidence that ethanol acts on a target in Loop 2 of the extracellular domain of alpha1 glycine receptors. J Neurochem 102: 2097–2109, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza N, Reiken S, Ondrias K, Yang YM, Matkovich S, Marks AR. Protein kinase A and two phosphatases are components of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor macromolecular signaling complex. J Biol Chem 277: 39397–39400, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, Berger AJ. Mechanisms for the modulation of native glycine receptor channels by ethanol. J Neurophysiol 91: 2685–2695, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, O'Brien JA, Berger AJ. Developmental changes in the modulation of synaptic glycine receptors by ethanol. J Neurophysiol 84: 2409–2416, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudzinska J, Schemm R, Haeger S, Nicke A, Schmalzing G, Betz H, Laube B. The beta subunit determines the ligand binding properties of synaptic glycine receptors. Neuron 45: 727–739, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Huang LY. Cross-modulation of glycine-activated Cl− channels by protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent protein kinase in the rat. J Physiol 506: 331–339, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch 391: 85–100, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm MK, Criswell HE, Breese GR. Calcium release from presynaptic internal stores is required for ethanol to increase spontaneous gamma-aminobutyric acid release onto cerebellum Purkinje neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323: 356–364, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm MK, Weinberg RJ, Criswell HE, Breese GR. The PLC/IP3R/PKC pathway is required for ethanol-enhanced GABA release. Neuropharmacology 58: 1179–1186, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JW. Molecular structure and function of the glycine receptor chloride channel. Physiol Rev 84: 1051–1095, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malosio ML, Marquèze-Pouey B, Kuhse J, Betz H. Widespread expression of glycine receptor subunit mRNAs in the adult and developing rat brain. EMBO J 10: 2401–2409, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiha FS. Strain dependent effects of ethanol on mouse brain and liver alcohol- and aldehyde-dehydrogenase. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 7: 189–192, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Kirsch J, Betz H, Langosch D. Identification of a gephyrin binding motif on the glycine receptor beta subunit. Neuron 15: 563–572, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, Mascia MP, Valenzuela CF, Hanson KK, Greenblatt EP, Harris RA, Harrison NL. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature 389: 385–389, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DI, Trudell JR, Crawford DK, Alkana RL, Davies DL. Targets for ethanol action and antagonism in Loop 2 of the extracellular domain of glycine receptors. J Neurochem 106: 1337–1349, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DI, Trudell JR, Crawford DK, Alkana RL, Davies DL. Molecular targets and mechanisms for ethanol action in glycine receptors. Pharmacol Ther 127: 53–65, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto C, Papa D, Hubner M, Mou TC, Lushington GH, Seifert R. Activation and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase isoforms by forskolin analogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325: 27–36, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Martin L, Cerda F, Jimenez V, Fuentealba J, Munoz B, Aguayo LG, Guzman L. Inhibition of the ethanol-induced potentiation of alpha1 glycine receptor by a small peptide that interferes with Gbetagamma binding. J Biol Chem 287: 40713–40721, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R. Alcoholism: a systems approach from molecular physiology to addictive behavior. Physiol Rev 89: 649–705, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streb H, Irvine RF, Berridge MJ, Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature 306: 67–69, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TS, Tu H, Wang Z, Bezprozvanny I. Modulation of type 1 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor function by protein kinase A and protein phosphatase 1alpha. J Neurosci 23: 403–415, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia JC, Aguayo LG. Changes in the properties of developing glycine receptors in cultured mouse spinal neurons. Synapse 28: 185–194, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau LE, Fang Y, Haydon PG. Modulation of an early step in the secretory machinery in hippocampal nerve terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7163–7168, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zundert B, Alvarez FJ, Tapia JC, Yeh HH, Diaz E, Aguayo LG. Developmental-dependent action of microtubule depolymerization on the function and structure of synaptic glycine receptor clusters in spinal neurons. J Neurophysiol 91: 1036–1049, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JH, Tao L, Ren J, Schaefer R, Krnjevic K, Liu PL, Schiller DA, McArdle JJ. Ethanol potentiation of glycine-induced responses in dissociated neurons of rat ventral tegmental area. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296: 77–83, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yevenes GE, Moraga-Cid G, Avila A, Guzman L, Figueroa M, Peoples RW, Aguayo LG. Molecular requirements for ethanol differential allosteric modulation of glycine receptors based on selective Gbetagamma modulation. J Biol Chem 285: 30203–30213, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yevenes GE, Moraga-Cid G, Peoples RW, Schmalzing G, Aguayo LG. A selective G betagamma-linked intracellular mechanism for modulation of a ligand-gated ion channel by ethanol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20523–20528, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yevenes GE, Moraga-Cid G, Romo X, Aguayo LG. Activated G protein alpha s subunits increase the ethanol sensitivity of human glycine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 339: 386–393, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yevenes GE, Peoples RW, Tapia JC, Parodi J, Soto X, Olate J, Aguayo LG. Modulation of glycine-activated ion channel function by G-protein betagamma subunits. Nat Neurosci 6: 819–824, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yevenes GE, Zeilhofer HU. Allosteric modulation of glycine receptors. Br J Pharmacol 164: 224–236, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Ye JH. The role of G proteins in the activity and ethanol modulation of glycine-induced currents in rat neurons freshly isolated from the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res 1033: 102–108, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziskind-Conhaim L, Gao BX, Hinckley C. Ethanol dual modulatory actions on spontaneous postsynaptic currents in spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 89: 806–813, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]