Abstract

Low ethanol yields on xylose hamper economically viable ethanol production from hemicellulose-rich plant material with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. A major obstacle is the limited capacity of yeast for anaerobic reoxidation of NADH. Net reoxidation of NADH could potentially be achieved by channeling carbon fluxes through a recombinant phosphoketolase pathway. By heterologous expression of phosphotransacetylase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase in combination with the native phosphoketolase, we installed a functional phosphoketolase pathway in the xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain TMB3001c. Consequently the ethanol yield was increased by 25% because less of the by-product xylitol was formed. The flux through the recombinant phosphoketolase pathway was about 30% of the optimum flux that would be required to completely eliminate xylitol and glycerol accumulation. Further overexpression of phosphoketolase, however, increased acetate accumulation and reduced the fermentation rate. By combining the phosphoketolase pathway with the ald6 mutation, which reduced acetate formation, a strain with an ethanol yield 20% higher and a xylose fermentation rate 40% higher than those of its parent was engineered.

Pentose-rich hemicellulose is a major constituent of abundant plant materials that are cheap substrates for bioethanol production (40). The preferred microorganism for alcoholic fermentation, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is not naturally capable of metabolizing the most abundant hemicellulosic pentoses, arabinose and xylose. Intense research in the past decade, therefore, focused on metabolic engineering of pentose utilization in yeast (3, 11, 15, 24) to establish an economically viable process from nonstarch substrates (32). For xylose, a recombinant pathway was installed by overexpression of the NAD(P)H-dependent xylose reductase and NAD+-dependent xylitol dehydrogenase from Pichia stipitis (7, 14). The different cofactor preferences in the two oxidoreductase reactions, however, cause an anaerobic redox balancing problem that manifests itself in the extensive accumulation of the reduced reaction intermediate xylitol and thus low ethanol yields (4, 11).

Engineering of redox metabolism to shift the cofactor usage of xylose reductase towards NADH alleviated xylitol formation and increased the ethanol yield, but the rate of fermentation was decreased significantly (1, 16). Presumably, NADPH-driven xylose reduction is necessary to sustain high fermentation rates (16), and increased cytosolic NADPH formation indeed increased xylose fermentation rates, in this case coupled with higher xylitol accumulation and lower ethanol yields (2). Unless an alternative, redox-neutral pathway is used for the initial utilization of xylose (12, 18), redox metabolism must thus be fine-tuned such that sufficient NADH is reoxidized to increase the ethanol yield without concomitantly decreasing the formation of NADPH that is necessary to drive the xylose reductase reaction at a high rate (25, 31). By identifying the underlying molecular changes in a xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strain that evolved from a 460-generation experiment (29), it was recently shown that indeed gene expression in redox metabolism was altered such that more NADH could be reoxidized and more NADPH formed (28). One possibility for engineering redox metabolism rationally is the phosphoketolase pathway, which leads to the net reoxidation of one NADH per xylose converted to ethanol (see Fig. 1). Phosphoketolases (EC 4.1.2.9) are catabolic key enzymes of many lactic acid and bifidobacteria (10) that convert xylulose-5-P to acetyl-P and glyceraldehyde-3-P and/or convert fructose-6-P to acetyl-P and erythrose-4-P (20, 23). This bacterial pathway would potentially allow achievement of the maximum theoretical yield of 0.51 g of ethanol per g of xylose, without affecting the NADPH/NADH usage ratio of the xylose reductase reaction.

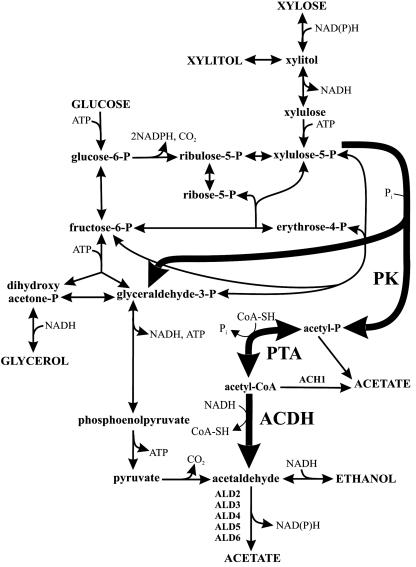

FIG. 1.

Cytosolic bioreaction network of S. cerevisiae. The bold arrows indicate the recombinant phosphoketolase pathway. Direct hydrolysis of acetyl-P may be catalyzed, for example, by [H+]ATPase (36). Abbreviations: PK, phosphoketolase; PTA, phosphotransacetylase; ACDH, acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acylating); ACH1, acetyl-CoA hydrolase; ALDx, aldehyde dehydrogenase isoenzymes.

Here, we describe metabolic engineering of a functional phosphoketolase pathway in the xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strain TMB3001c (7) that expresses xylose reductase, xylitol dehydrogenase, and xylulokinase from a chromosomal integration. During the course of this work, we realized that even low-level accumulation of acetate has a pronounced negative influence on the rate of xylose fermentation. By combining reduced acetate accumulation in an ald6 mutant (6) with the phosphoketolase pathway, we engineered a strain with an increased fermentation rate and ethanol yield.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and cultivation conditions.

The S. cerevisiae strains used here are listed in Table 1. All fermentation experiments were done in minimal medium (29) with 50 g each of glucose and xylose liter−1. Ethanol-dissolved ergosterol (Fluka) and Tween 80 (Sigma) were added to final concentrations of 0.01 and 0.42 g liter−1, respectively. The pH was maintained above 4.5 by adding 100 mM citric acid buffer (pH 5.5). Cultures were grown in 175-ml serum bottles, filled with 150 ml of medium, and stirred magnetically at 100 rpm and 30°C. CO2 accumulation was prevented by penetrating the rubber septum with a needle (0.45 by 10 mm).

TABLE 1.

Strains used

| Strain or population | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| TMB3001c | CEN.PK113-1C (MATaleu2-3,112 trp1-289 ura3-52 his3-Δ1 MAL2-8c SUC2), his3::YIpXR/XDH/XK | 7 |

| TMB3001c-p6XFP | TMB3001c expressing the phosphoketolase from B. lactis | This study |

| TMB3001c-p5EHADH2 | TMB3001c expressing the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase from E. histolytica | This study |

| TMB3001c-p4PTA | TMB3001c expressing the phosphotransacetylase from B. subtilis | This study |

| TMB3001c-p4PTA/p5EHADH2 | TMB3001c expressing phosphotransacetylase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | This study |

| TMB3001c-p6XFP/p4PTA/p5EHADH2 | TMB3001c expressing phosphoketolase, phosphotransacetylase, and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | This study |

| TMBALD6c | TMB3001c ald6::KanMX | This study |

| TMBALD6c-p4PTA/p5EHADH2 | TMBALD6c expressing phosphotransacetylase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | This study |

Analytical methods.

Cell growth was monitored by monitoring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Cellular dry weight (DW) was determined from at least three 2-ml culture aliquots that were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min in predried and preweighed microcentrifuge tubes, washed once with water, and dried at 110°C for 24 h to constant weight. Commercially available kits were used for enzymatic determination of glucose (Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.), xylose (Medichem, Steinenbronn, Germany), xylitol (R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany), acetate (R-Biopharm), and glycerol (Sigma). Ethanol was measured by gas chromatography as was described previously (27).

Determination of physiological parameters and intracellular metabolic fluxes.

Maximum exponential growth rates on glucose were determined by log-linear regression of OD600 versus time, with the growth rate as the regression coefficient. The biomass yield (Yx/s) was determined as the coefficient of linear regression of biomass concentration (DW) versus substrate concentration (S)during exponential growth phase on glucose. The biomass concentration was estimated from OD600-to-DW correlations determined for each culture after glucose depletion (40 to 60 h after inoculation) and prior to the termination of the experiment (100 to 120 h after inoculation). Ethanol, xylitol, acetate, and glycerol yields on glucose or xylose were calculated by linear regression of by-product versus substrate concentrations during exponential growth on glucose or after glucose depletion until the end of the experiment, respectively. The specific xylose uptake rate was determined as the ratio of the linear regression coefficient of xylose concentration versus time to the average biomass concentration measured after glucose depletion. An ethanol evaporation constant of 0.001 h−1 was determined by monitoring the decrease in ethanol concentration in an identical fermentation setup containing 100-, 50-, and 25-g l−1 ethanol solutions in the same minimal medium.

The previously reported stoichiometric model (34) was used to estimate intracellular carbon fluxes during the xylose consumption phase of the above anaerobic batch fermentations. To estimate the fluxes through the phosphoketolase pathway, the corresponding pathway was implemented in the model as a single reaction that converts xylulose-5-P and NADH to glyceraldehyde-3-P, acetaldehyde, and NAD+. Since xylose reductase is also able to convert dihydroxyacetone phosphate to glycerol-3-P using both NADH and NADPH (17), the in vivo cofactor usage of xylose reductase is not assessable with a stoichiometric model. Thus, the cofactor usage ratio of the xylose reductase was assumed to remain unaltered, to maintain a determined system of linear equations (30). This assumption is supported by unaltered rates of xylose uptake and acetate formation upon installation of the pathway. The flux to ethanol was defined as a free flux, whose computed values were compared with the experimentally determined ethanol production rates. The computed free fluxes were always within 14% of the experimental values, thus confirming the reliability of the employed stoichiometric model.

Molecular biology procedures.

The ald6 (YPL061W) mutant of TMBALD6c was generated with the homolog flanking region approach (33). Briefly, the kanMX4 cassette of the yeast strain Y02767 (BY4741 MATa his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0 met15-Δ0 ura3-Δ0 YPL061W::kanMX4) from the gene deletion project (37) was PCR amplified with primers that were complementary to sequences 500 bp upstream (5′-GACAAAAGAAAAACGACCGAAAAGG-3′) and downstream (5′-ATATGATCTCTGATGGCGAAATGG-3′) of the deleted gene. The PCR product was used directly to transform TMB3001c with the lithium acetate method (9). Transformants were confirmed by PCR using each of the above primers in combination with the corresponding kanMX4-specific primer KanB (5′-CTGCAGCGAGGAGCCGTAAT-3′) or KanC (5′-TGATTTTGATGACGAGCGTAA-3′).

The d-xylulose-5-P/d-fructose-6-P phosphoketolase gene xfp from Bifidobacterium lactis was cloned as an EcoRI-HindIII fragment from the vector pFPK5 (20) under the control of the constitutive, truncated HXT7 promoter of the p426 (URA3) plasmid (13) to yield p6XFP. Similarly, the Entamoeba histolytica acetaldehyde dehydrogenase gene EhADH2 was cloned as a BamHI-XbaI fragment from pET/EhADH2 (38) into the BamHI-SpeI-digested p425 (LEU2) plasmid (13) to generate p5EHADH2. Finally, the phosphotransacetylase gene pta was amplified from genomic DNA of Bacillus subtilis RB50:PRF69 (22), using the forward primer 5′-CGGGATCCATGGCAGATTTATTTTCAACAGTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCATCGATGTCGAGAGCTGCCATTGTCTCC-3′. The resulting PCR product was ligated into the BamHI-ClaI-digested p424 (TRP1) plasmid (13) to obtain p4PTA. For comparative physiological analysis, all strains contained three plasmids, with or without insert, so that supplementation with amino acids was not necessary.

Phosphoketolase activity assay.

Cell extracts were prepared from mid-exponential-growth-phase cultures at an OD600 of about 1 in minimal medium with 20 g of glucose liter−1 or 5 g of galactose liter−1 plus 20 g of xylose liter−1. Cell pellets were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with deionized water, and resuspended in 50 mM histidine-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing 20 mM KH2PO4-Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0), 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM MgSO4. The suspension was vortexed with glass beads (diameter, 0.5 mm) at 4°C for 5 min, incubated on ice for 5 min, and vortexed again for 5 min. Cell debris and glass beads were separated by centrifugation at 20,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min. In vitro activity of d-xylulose-5-P phosphoketolase was determined by measuring the acetyl-P formed after addition of ribose-5-P that was converted to xylulose-5-P by the endogenous ribose-5-P isomerase and ribulose-5-P epimerase in crude extracts as described elsewhere (J. Thykaer et al., unpublished data). The acetate produced in the assay mixture was then determined enzymatically by subtracting the acetate that was formed in an assay mixture without ribose-5-P from the assay mixture containing ribose-5-P. The total protein content was determined with a commercially available kit (Beckman). Specific activities were expressed as units per milligram of protein, where 1 U is defined as formation of 1 μmol of acetate per min.

RESULTS

Installing a phosphoketolase pathway.

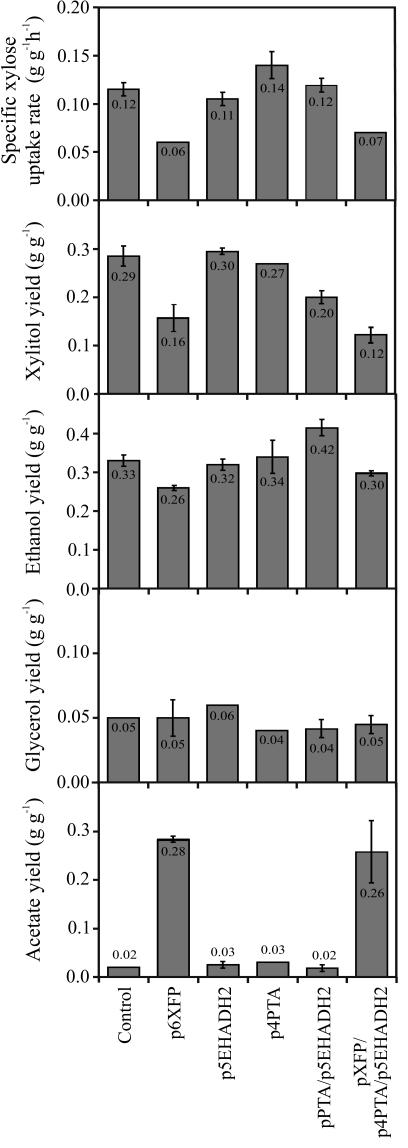

To engineer the phosphoketolase pathway into the xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strain TMB3001c (Fig. 1), we expressed different combinations of the B. lactis d-xylulose-5-P/d-fructose-6-P phosphoketolase gene xfp, the B. subtilis phosphotransacetylase gene pta, and the E. histolytica acetaldehyde dehydrogenase gene EhADH2. During the initial glucose consumption phase in batch cultures with 50 g (each) of glucose and xylose liter−1, all phosphotransacetylase-expressing strains attained about 30% lower biomass yields, and all other physiological parameters were similar to those of the control strain (data not shown). During the subsequent xylose consumption phase, phosphoketolase-expressing strains exhibited strongly reduced specific rates of uptake of xylose and lower formation of the by-product xylitol (Fig. 2). The most prominent effect of phosphoketolase expression was the extremely high level of accumulation of acetate. While individual expression of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase and phosphotransacetylase had only negligible effects, concomitant overexpression of both genes surprisingly increased the ethanol yield by about 25% over that of the TMB3001c control (Fig. 2). This yield increase was achieved by a lower rate of formation of xylitol while the high rate of uptake of xylose remained unaltered.

FIG. 2.

Physiological parameters of S. cerevisiae TMB3001c expressing various combinations of the phosphoketolase pathway genes during the xylose consumption phase (30 h up to about 120 h) in anaerobic batch cultures with 50 g of glucose liter−1 and 50 g of xylose liter−1. Average and deviation for two independent experiments are shown.

Since heterologous expression of phosphoketolase was apparently not necessary to achieve the desired ethanol yield increase, we hypothesized endogenous phosphoketolase activity in S. cerevisiae, as was earlier described during growth on xylose (8). Using an in vitro enzyme assay, we verified this endogenous activity (Table 2). Endogenous phosphoketolase activity was detected during growth on glucose and about doubled during growth on galactose plus xylose. Heterologous overexpression of phosphoketolase further increased phosphoketolase activity about 10-fold in TMB3001c-p6XFP/p5EHADH2/p4PTA. The apparent induction of the recombinant phosphoketolase on galactose plus xylose may be explained by the moderate downregulation of the truncated HXT7 promoter on glucose (13).

TABLE 2.

Specific xylulose-5-P phosphoketolase activitya in S. cerevisiae expressing different combinations of the phosphoketolase pathway genes

| Strain | Carbon source | Sp act (mU [mg protein]−1)b |

|---|---|---|

| TMB3001c | Glucose | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| Galactose + xylose | 2.5 ± 0.1 | |

| TMB3001c-p4PTA/p5EHADH2 | Glucose | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| Galactose + xylose | 2.2 ± 0.1 | |

| TMB3001c-p6XFP/p4PTA/p5EHADH2 | Glucose | 13.5 ± 1.0 |

| Galactose + xylose | 26.8 ± 7.8 |

Phosphotransacetylase activities were below detection level in TMB3001c and 169 ± 8 and 139 ± 18 mU mg−1 for the other two strains.

The average and the deviation were determined from two independent experiments.

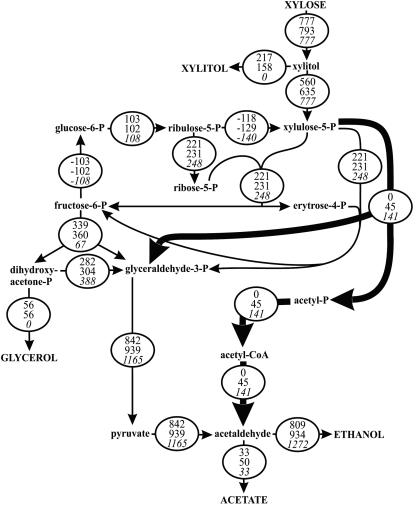

During the xylose consumption phase, the flux through the phosphoketolase pathway in TMB3001c expressing phosphotransacetylase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase was 45 μmol g−1 h−1 or about 6% of the xylose uptake rate (Fig. 3). While this flux rerouting clearly increased the ethanol yield, maximum theoretical ethanol production would require an about threefold-higher phosphoketolase flux to eliminate glycerol and xylitol accumulation. Attempting to increase the phosphoketolase pathway flux by overexpression of the heterologous phosphoketolase resulted in high acetate accumulation (Fig. 2). Hence, we expressed all three phosphoketolase pathway enzymes in the ald6 mutant of TMB3001c that lacks the constitutive cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase, which is the major acetate-producing isoenzyme from acetaldehyde (6, 21). This strategy reduced acetate formation only modestly (data not shown), indicating that phosphoketolase-dependent acetate formation originates from the hydrolysis of either acetyl-P (36) or acetyl-CoA (5) rather than from acetaldehyde. Hence, it appears that higher activities of phosphotransacetylase and/or acetaldehyde dehydrogenase may be necessary to prevent phosphoketolase pathway-based acetate formation.

FIG. 3.

Specific intracellular carbon fluxes (μmol g DW−1 h−1) during xylose consumption in anaerobic batch experiments. Fluxes for TMB3001c (upper values) and TMB3001c-p4PTA/p5EHADH2 (middle values) were estimated from the experimental data shown in Fig. 2. Average values of duplicate experiments with deviations within 10% are given. The lower values (italics) represent the flux distribution that is required for maximum theoretical ethanol production from the xylose uptake rate of TMB3001c.

Metabolic engineering of reduced acetate formation improves xylose catabolism.

Circumstantially, the strongly decreased xylose fermentation rate upon phosphoketolase overexpression (Fig. 2) and upon deletion of the glucose-6-P dehydrogenase (16) was accompanied by a drastically higher accumulation of acetate. Thus, we investigated the effect of extracellular acetate accumulation on xylose fermentation by comparing fermentation performance of TMB3001c and the aldehyde dehydrogenase deletion mutant TMBALD6c in anaerobic batch culture with a 50-g liter−1 concentration each of glucose and xylose. During growth on glucose, acetate formation of TMBALD6c was below detection level, whereas TMB3001c accumulated up to 1.5 g of acetate liter−1 (data not shown). During xylose consumption, TMBALD6c produced much less acetate than TMB3001c but exhibited a 50% higher rate of specific xylose uptake.

To verify that the higher rate of xylose consumption was indeed caused by the low level of acetate accumulation in the aldehyde dehydrogenase deletion mutant, we increased the acetate concentration artificially upon glucose depletion from 0 and 1.5 g liter−1 to 2 and 3.5 g liter−1 for TMBALD6c and TMB3001c, respectively. Consequently, only the specific xylose uptake rates but not the product yields on xylose were significantly reduced in both strains: from 0.12 to 0.07 g g−1 h−1 in TMB3001c and from 0.18 to 0.12 g g−1 h−1 in TMBALD6c. Thus, TMBALD6c with added acetate exhibited about the same uptake rate as TMB3001c without. These results provide strong evidence that acetate has a negative effect on the xylose fermentation rate, which appears to go beyond the well-known growth-inhibiting effect of acetate (11, 19).

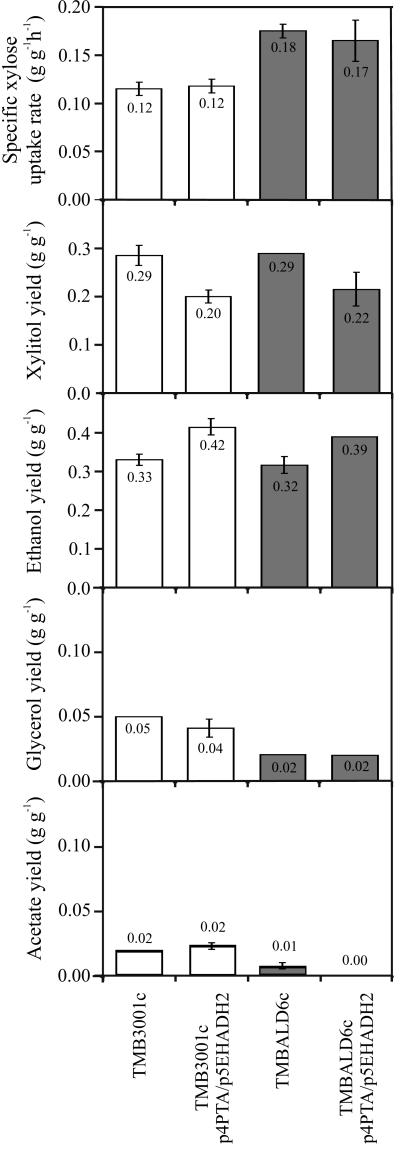

Establishment of the phosphoketolase pathway in TMBALD6c.

Since the simultaneous increase of ethanol yield and the xylose fermentation rate would clearly be desirable, we combined the two strategies described above by expression of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase and phosphotransacetylase in TMBALD6c. The resulting strain, TMBALD6c-p5EHADH2/p4PTA, maintained the high ethanol yield of the phosphoketolase pathway strain TMB3001c-p5EHADH2/p4PTA but also the high specific xylose uptake rate of the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase deletion mutant TMBALD6c (Fig. 4). Thus, both important characteristics could be combined without significant loss of the previously observed improvements.

FIG. 4.

Physiological parameters of TMBALD6c and TMBALD6c-p4PTA/p5EHADH2 during xylose consumption in anaerobic batch culture with 50 g of glucose liter−1 and 50 g of xylose liter−1. TMB3001c and TMB3001c-p4PTA/p5EHADH2 (white bars) data from Fig. 2 are shown for comparison. The average and deviation for two independent experiments are displayed.

DISCUSSION

We describe here successful establishment of the phosphoketolase pathway in a recombinant, xylose-utilizing S. cerevisiaestrain. In combination with the endogenous phosphoketolase activity (8), heterologous expression of phosphotransacetylase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase was sufficient to achieve significant flux through this recombinant pathway. This metabolic engineering strategy improved the ethanol yield on xylose by about 25%, without affecting the xylose fermentation rate. Somewhat independently of the phosphoketolase pathway, we identified acetate as a strong inhibitor of xylose fermentation in yeast. Deletion of the NADPH-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase-encoding ALD6 gene strongly reduced acetate formation, thereby increasing the rate of xylose fermentation for TMBALD6c by about 50% over that for TMB3001c. Notably, the ethanol yield remained largely unaltered. Since strains with increased ethanol yield and an increased xylose fermentation rate are important for commercial establishment of an ethanol production process, we combined reduction of acetate formation with the phosphoketolase pathway. Expression of the two phosphoketolase pathway enzymes phosphotransacetylase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase in the low acetate producer TMBALD6c yielded a strain that fermented xylose about 40% faster and produced ethanol with a 20% higher yield than TMB3001c.

Metabolic engineering of xylose metabolism in yeast typically has either increased ethanol yields at the expense of the fermentation rate (1, 16) or increased fermentation rates while reducing the ethanol yield (2, 39). A current intermediate success is an increased fermentation rate without yield reduction when using xylose isomerase (18). This strategy holds great promise, though, because it may avoid the redox problem that is caused by the consecutive redox reactions used in virtually all other yeast strains. Two notable exceptions to the above trade-off rule were reported recently, both affecting redox balancing. In the first, ammonium assimilation was modified by deleting the NADPH-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase GDH1 and overexpressing the NADH-dependent isoenzyme GDH2 (25). The reduced xylitol secretion caused a significant ethanol yield increase and a concomitant xylose fermentation rate increase of 15%. Since this NADH-reoxidizing reaction is stoichiometrically coupled to the anabolic ammonium requirement, however, the possibilities for complete elimination of xylitol and glycerol accumulation appear to be limited. In the second case, xylose reductase expression levels were increased in a zwf1 mutant with an interrupted pentose phosphate pathway (17). The optimal expression level increased the ethanol yield by 10% and the fermentation rate by 120%. The drawback of this approach was a 150%-higher rate of glycerol production, because xylose reductase also catalyzes the conversion of dihydroxyacetone-P to glycerol-3-P. In contrast to the above two approaches, the phosphoketolase pathway strategy introduces an alternative catabolic pathway that channels carbon fluxes directly to ethanol without at the same time interfering with other metabolic processes. Since this pathway consumes more NADH than it requires for the conversion of xylose to ethanol, it appears to be a promising strategy to further improve production of ethanol from xylose. To take full advantage of this potential, the enzymatic activities of phosphoketolase, phosphotransacetylase, and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase need to be increased and fine-tuned, possibly by using evolutionary approaches (26), which have successfully generated such fine-tuned, pentose-fermenting yeast strains (3, 28, 29, 35).

Acknowledgments

We thank Bärbel Hahn-Hägerdal for sharing S. cerevisiae TMB3001c, Jörg Hauf for Y02767, Leo Meile for providing the xfp gene from B. lactis, Samuel L. Stanley, Jr., for the EhADH2 gene from E. histolytica, Eckhard Boles for the plasmids p424, p425, and p426, and Jette Thykae and Jens Nielsen for sharing the phosphoketolase assay protocol prior to publication.

This work was supported by the Swiss Bundesamt für Bildung und Wissenschaft (BBW) within the BIO-HUG project of the European Commission Framework V.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderlund, M., P. Radstrom, and B. Hahn-Hägerdal. 2001. Expression of bifunctional enzymes with xylose reductase and xylitol dehydrogenase activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae alters product formation during xylose fermentation. Metab. Eng. 3:226-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aristidou, A., J. Londesborough, M. Penttilä, P. Richard, L. Rouhonen, H. Soderlund, A. Teleman, and M. Toivari. 1999. Transformed microorganisms with improved properties. Patent WO 99/46363.

- 3.Becker, J., and E. Boles. 2003. A modified Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain that consumes l-arabinose and produces ethanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4144-4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruinenberg, P. M., P. H. M. De Bot, J. P. van Dijken, and W. A. Scheffers. 1984. NADH-linked aldose reductase: the key to ethanolic fermentation of xylose by yeasts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19:256-260. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buu, L. M., Y. C. Chen, and F. J. Lee. 2003. Functional characterization and localization of acetyl-CoA hydrolase, Ach1p, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278:17203-17209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eglinton, J. M., A. J. Heinrich, A. P. Pollnitz, P. Langridge, P. A. Henschke, and M. de Barros Lopes. 2002. Decreasing acetic acid accumulation by a glycerol overproducing strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by deleting the ALD6 aldehyde dehydrogenase gene. Yeast 19:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eliasson, A., C. Christensson, C. F. Wahlbom, and B. Hahn-Hägerdal. 2000. Anaerobic xylose fermentation by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae carrying XYL1, XYL2, and XKS1 in mineral medium chemostat cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3381-3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans, C. T., and C. Ratledge. 1984. Induction of xylulose-5-phosphate in a variety of yeasts grown on D-xylose: the key to efficient xylose metabolism. Arch. Microbiol. 139:48-52. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gietz, R. D., and R. A. Woods. 2002. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 350:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottschalk, G. 1986. Bacterial metabolism, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 11.Hahn-Hägerdal, B., C. F. Wahlbom, M. Gardonyi, W. H. van Zyl, R. R. Cordero Otero, and L. J. Jönsson. 2001. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for xylose utilization. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 73:53-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harhangi, H. R., A. S. Akhmanova, R. Emmens, C. van der Drift, W. T. de Laat, J. P. van Dijken, M. S. Jetten, J. T. Pronk, and H. J. Op den Camp. 2003. Xylose metabolism in the anaerobic fungus Piromyces sp. strain E2 follows the bacterial pathway. Arch. Microbiol. 180:134-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauf, J., F. K. Zimmermann, and S. Müller. 2000. Simultaneous genomic overexpression of seven glycolytic enzymes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 26:688-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho, N. W. Y., Z. Chen, and A. P. Brainard. 1998. Genetically engineered Saccharomyces yeast capable of effective cofermentation of glucose and xylose. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 64:1852-1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho, N. W. Y., Z. Chen, A. P. Brainard, and M. Sedlak. 1999. Successful design and development of genetically engineered Saccharomyces yeasts for effective cofermentation of glucose and xylose from cellulosic biomass to fuel ethanol. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 65:163-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeppsson, M., B. Johansson, B. Hahn-Hägerdal, and M. F. Gorwa-Grauslund. 2002. Reduced oxidative pentose phosphate pathway flux in recombinant xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains improves the ethanol yield from xylose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1604-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeppsson, M., K. Traff, B. Johansson, B. Hahn-Hägerdal, and M. F. Gorwa-Grauslund. 2003. Effect of enhanced xylose reductase activity on xylose consumption and product distribution in xylose-fermenting recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 3:167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuyper, M., H. R. Harhangi, A. K. Stave, A. A. Winkler, M. S. Jetten, W. T. de Laat, J. J. den Ridder, H. J. Op den Camp, J. P. van Dijken, and J. T. Pronk. 2003. High-level functional expression of a fungal xylose isomerase: the key to efficient ethanolic fermentation of xylose by Saccharomyces cerevisiae? FEMS Yeast Res. 4:69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasko, D. R., N. Zamboni, and U. Sauer. 2000. The bacterial response to acetate challenge: a comparison of tolerance between species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 54:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meile, L., L. M. Rohr, T. A. Geissmann, M. Herensperger, and M. Teuber. 2001. Characterization of the D-xylulose-5-phosphate/D-fructose-6-phosphate phosphoketolase gene (xfp) from Bifidobacterium lactis. J. Bacteriol. 183:2929-2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro-Aviño, J. P., R. Prasad, V. J. Miralles, R. M. Benito, and R. Serrano. 1999. A proposal for nomenclature of aldehyde dehydrogenases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and characterization of the stress-induced ALD2 and ALD3 genes. Yeast 15:829-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perkins, J. B., A. Sloma, T. Hermann, K. Theriault, E. Zachgo, T. Erdenberger, N. Hannett, N. P. Chatterjee, V. Williams II, G. A. Rufo, Jr., R. Hatch, and J. Pero. 1999. Genetic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for the commercial production of riboflavin. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 22:8-18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Posthuma, C. C., R. Bader, R. Engelmann, P. W. Postma, W. Hengstenberg, and P. H. Pouwels. 2002. Expression of the xylulose 5-phosphate phosphoketolase gene, xpkA, from Lactobacillus pentosus MD363 is induced by sugars that are fermented via the phosphoketolase pathway and is repressed by glucose mediated by CcpA and the mannose phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:831-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richard, P., R. Verho, M. Putkonen, J. Londesborough, and M. Penttilä. 2003. Production of ethanol from L-arabinose by Saccharomyces cerevisiae containing a fungal L-arabinose pathway. FEMS Yeast Res. 3:185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roca, C., J. Nielsen, and L. Olsson. 2003. Metabolic engineering of ammonium assimilation in xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae improves ethanol production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4732-4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauer, U. 2001. Evolutionary engineering of industrially important microbial phenotypes. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 73:129-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauer, U., V. Hatzimanikatis, H.-P. Hohmann, M. Manneberg, A. P. G. M. van Loon, and J. E. Bailey. 1996. Physiology and metabolic fluxes of wild-type and riboflavin-producing Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3687-3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonderegger, M., M. Jeppson, B. Hahn-Hägerdal, and U. Sauer. 2004. Molecular basis for anaerobic growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on xylose, investigated by global gene expression and metabolic flux analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2307-2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonderegger, M., and U. Sauer. 2003. Evolutionary engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for anaerobic growth on xylose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1990-1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephanopoulos, G. N., A. A. Aristidou, and J. Nielsen. 1998. Metabolic engineering: principles and methodologies. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 31.Verho, R., P. Richard, P. H. Jonson, L. Sundqvist, J. Londesborough, and M. Penttilä. 2002. Identification of the first fungal NADP-GAPDH from Kluyveromyces lactis. Biochemistry 41:13833-13838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Von Sivers, M., and G. Zacchi. 1995. A techno-economical comparison of three processes for the production of ethanol from pine. Biores. Technol. 41:43-52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann, and P. Philippsen. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10:1793-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wahlbom, C. F., and B. Hahn-Hägerdal. 2002. Furfural, 5-hydroxymethyl furfural and acetoin act as external electron acceptors during anaerobic fermentation of xylose by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 78:172-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wahlbom, C. F., W. H. van Zyl, L. J. Jonsson, B. Hahn-Hägerdal, and R. R. Otero. 2003. Generation of the improved recombinant xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae TMB3400 by random mutagenesis and physiological comparison with Pichia stipitis CBS8054. FEMS Yeast Res. 3:319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, G., and D. S. Perlin. 1997. Probing energy coupling in the yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase with acetyl phosphate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 344:309-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winzeler, E. A., D. D. Shoemaker, A. Astromoff, H. Liang, K. Anderson, B. Andre, R. Bangham, R. Benito, J. D. Boeke, H. Bussey, A. M. Chu, C. Connelly, K. Davis, F. Dietrich, S. W. Dow, M. El Bakkoury, F. Foury, S. H. Friend, E. Gentalen, G. Giaever, J. H. Hegemann, T. Jones, M. Laub, H. Liao, R. W. Davis, et al. 1999. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285:901-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yong, T.-S., E. Li, D. Clark, and S. L. J. Stanley. 1996. Complementation of an Escherichia coli adhE mutant by the Entamoeba histolytica EhADH2 gene provides a method for the identification of new antiamebic drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6464-6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaldivar, J., A. Borges, B. Johansson, H. P. Smits, S. G. Villas-Boas, J. Nielsen, and L. Olsson. 2002. Fermentation performance and intracellular metabolite patterns in laboratory and industrial xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 59:436-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaldivar, J., J. Nielsen, and L. Olsson. 2001. Fuel ethanol production from lignocellulose: a challenge for metabolic engineering and process integration. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 56:17-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]