Abstract

Anoxic bottom water from Mono Lake, California, can biologically reduce added arsenate without any addition of electron donors. Of the possible in situ inorganic electron donors present, only sulfide was sufficiently abundant to drive this reaction. We tested the ability of sulfide to serve as an electron donor for arsenate reduction in experiments with lake water. Reduction of arsenate to arsenite occurred simultaneously with the removal of sulfide. No loss of sulfide occurred in controls without arsenate or in sterilized samples containing both arsenate and sulfide. The rate of arsenate reduction in lake water was dependent on the amount of available arsenate. We enriched for a bacterium that could achieve growth with sulfide and arsenate in a defined, mineral medium and purified it by serial dilution. The isolate, strain MLMS-1, is a gram-negative, motile curved rod that grows by oxidizing sulfide to sulfate while reducing arsenate to arsenite. Chemoautotrophy was confirmed by the incorporation of H14CO3− into dark-incubated cells, but preliminary gene probing tests with primers for ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase did not yield PCR-amplified products. Alignment of 16S rRNA sequences indicated that strain MLMS-1 was in the δ-Proteobacteria, located near sulfate reducers like Desulfobulbus sp. (88 to 90% similarity) but more closely related (97%) to unidentified sequences amplified previously from Mono Lake. However, strain MLMS-1 does not grow with sulfate as its electron acceptor.

Dissimilatory arsenate reduction (DAsR) occurs in the anoxic water column of Mono Lake, California, a closed-basin, alkaline (pH 9.8), hypersaline (salinity, 90 g liter−1) lake whose waters have a high concentration of inorganic arsenic oxyanions (∼200 μM) (27). Follow-up experiments in the laboratory were subsequently conducted with arsenate-amended bottom water with the goal of determining the microbial agents of DAsR in Mono Lake (10). We noted that when we amended the samples with 1 to 2 mM arsenate this oxyanion was consumed steadily and entirely over an incubation period of several days. This suggested that DAsR in these samples was not constrained by the availability of an electron donor. Indeed, when we amended the water samples with various organic substrates (e.g., lactate, acetate, malate, and glucose) we saw little or no enhanced rates of DAsR activity. Hence, either the lake water contained a surfeit of labile organic substrates to fuel DAsR or an inorganic electron donor was driving the observed DAsR. Amendment of bottom water with 2 mM arsenate (10) also increased rates of DAsR by ∼300-fold over the highest measured in situ rates (27). This reinforced the idea that arsenate reduction in these samples was limited by the availability of an electron acceptor rather than by the availability of an electron donor.

Mono Lake contains exceptionally high levels of dissolved organic carbon (∼7 mM), but most of this material is refractory to microbial mineralization. Pulses of labile organics are released seasonally as a consequence of the die-offs of spring and fall blooms of phytoplankton and zooplankton, respectively (24). Alternatively, reduced substances (e.g., sulfide, ammonia, and methane) are abundant in Mono Lake bottom waters during thermal stratification, and especially so during periods of prolonged stratification (meromixis) caused by salinity (14, 19). In this paper we report the link between microbial sulfide oxidation and arsenate reduction in samples of anoxic bottom water from Mono Lake and the isolation of strain MLMS-1, a δ-Proteobacterium that grows as a chemoautotroph by oxidizing sulfide to sulfate while reducing arsenate to arsenite.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Lake water incubations.

Samples of anoxic Mono Lake bottom water were shipped from the lake in completely filled glass containers and stored for up to 3 months at 5°C before experiments began. Incubations were conducted in 10-ml glass syringes as described previously (10, 26, 27). Briefly, lake water was drawn into 10-ml glass syringes while N2 gas was bubbled through the water to maintain anoxic conditions. The syringes were sealed with rubber-plugged syringe needle caps (to allow for injection of reagents) and incubated in the dark at room temperature (∼20°C). Water samples were injected with solutions of sodium arsenate-sodium sulfide, and controls were sterilized by passage through 0.2-μm-pore-size filters before amendments were injected. Subsamples from time courses were taken by removing the hubs and expressing the samples through nylon centrifuge filters (pore size, 0.2 μm). Subsamples were stored frozen for up to 2 weeks before analysis.

Isolation of strain MLMS-1.

An anaerobic enrichment culture was established by inoculating a defined mineral salts medium (see below) with a fresh inoculum (0.5 ml) taken from the lake water incubation samples that demonstrated loss of arsenate and sulfide and production of arsenite. The mineral salts medium was essentially the same as the one used previously for growing heterotrophic, haloalkaliphilic (pH 9.8; NaCl, 90 g/liter) arsenate respirers from Mono Lake (35). It differed by having a lower content of NaCl (60 g/liter) and no yeast extract nutrient supplement and sulfide (5 mM) was substituted for lactate as the electron donor, with arsenate (10 mM) as the electron acceptor. Periodic chemical spot checks of anions determined that the enrichment grew by consuming arsenate and sulfide, while producing arsenite and sulfate. It was transferred twice monthly over a 2-month period and then serially diluted to 10−8, and growth was confirmed at this highest dilution. We were not able to achieve growth of either the enrichment or the high dilution on a 0.3% phytagel-solidified medium of the same composition. However, purity of the culture was obtained by the serial dilution approach. This was confirmed by the uniform morphology of the cells, the occurrence of only a single band upon denatured gradient gel electrophoresis of the gene fragments amplified using universal Bacteria primers (10, 12), and the lack of any ambiguities in the 16S rRNA gene sequence after its successful amplification. In addition, this microorganism was found to have a severely constrained metabolism, being able to grow only with sulfide plus arsenate but not on a range of other autotrophic or heterotrophic substrates tested that could also have supported growth of potential contaminants (see Results). The purified culture was designated strain MLMS-1. Experiments were conducted with the medium described above to demonstrate arsenate-dependent growth with sulfide as the electron donor. Because strain MLMS-1 aligned closely with sulfate reducers (see Results), we also attempted to grow it as a heterotroph by using the medium described above but with 10 mM acetate, lactate, or acetate plus H2 as the electron donor and 10 mM sulfate as the electron acceptor. We also tested for growth on acetate with either oxygen (air) or 10 mM nitrate as the electron acceptor and individually with lactate (oxygen) and sulfide (nitrate).

Dark H14CO3− fixation.

The methods employed for dark H14CO3− fixation were similar to those detailed for strain MLHE-1 (26). Cell suspensions of strain MLMS-1 were prepared by growing anaerobic batch cultures (2 liters) in the mineral medium described above with sulfide and arsenate as the electron donor and acceptor, respectively. The cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in 240 ml of basal salts medium (final cell density, 5.1 × 107 cells/ml). This medium was modified to have lower concentrations of NaHCO3 (0.5 mM) and Na2CO3 (1.0 mM) to allow for better cellular incorporation of 14C. The suspensions were dispensed (20 ml) into serum bottles (57 ml; all manipulations were performed in an anaerobic glove box) and sealed under N2. The suspensions were injected with an electron donor (4 mM sulfide) and electron acceptor (12 mM arsenate), while controls either lacked these substances or the sulfide electron donor. Samples were injected with 5.3 μCi of NaH14CO3 and incubated in the dark at 20°C with constant rotary shaking (100 rpm) for 12 h. Suspensions were then filtered (pore size, 0.45 μm), and the filter was rinsed with 5 ml of sterile medium and acid fumed for 8 h in a desiccator. Residual radioactivity on the filters was counted by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

Analytical methods.

Arsenic speciation in lake water and in culture experiments was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Shimadzu VP series chromatograph with a UV-visual detector (SPD-10AVP) set at 210 nm. Arsenate and arsenite were separated by using two columns in series (Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H and Hamilton PRP X300) with a 0.016 N H2SO4 eluent (flow rate, 0.6 ml/min). Retention times for arsenate and arsenite under these conditions were 11.7 and 16.4 min, respectively. Sulfide was determined spectrophotometrically (3), and sulfate was measured by ion chromatography (26). Direct counts of bacteria were made by epifluorescence microscopy (9). Thioarsenite species present during culture incubations were determined by Frontier Geosciences (Seattle, Wash.) using ion chromatography-anion self-regenerating suppression-inductively coupled mass spectrometry (IC-ICPMS) as described elsewhere (42).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

The 16S rRNA gene from MLMS-1 was amplified by PCR with the EubA and EubB primers (7), cloned by using the TA cloning system (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.), and sequenced at the University of Pittsburgh DNA Sequencing Facility with forward and reverse sequencing primers (7, 15). Additional sequences were obtained from GenBank. Alignments were done by using Clustal X (13). Maximum parsimony trees were generated and sequence similarities were determined by using PHYLIP, version 3.6a or PAUP version 4.0b (6, 36). A total of 1,450 bases were analyzed, and bootstrap values were generated from 1,000 trees.

An attempt was made to obtain a partial sequence of the gene encoding the large subunit of ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCo) by PCR amplification of the gene with the RuBisCo form 1 cbbL and form II cbbM gene primers described by Elsaied and Naganuma (5). The forward 20-mer primer (5′-GACTTCACAAAGACGACGA-3′) corresponds to nucleotide positions 595 to 615 of the Anabaena strain 7120 cbbL gene (accession number L02520), while the reverse 20-mer primer (5′-TCGAACTTGATTTCTTTCCA-3′) corresponds to nucleotide positions 1387 to 1405 of the Anabaena strain 7120 cbbL gene (4). This primer set amplifies an approximately 800-bp fragment of the cbbL gene. Form II cbbM genes were amplified with primers cbbMf (5′-ATCATCAARCCSAARCTSGGCCTGCGTCCC-3′) and cbbMr (5′-MGAGGTGACSGCRCCGTGRCCRGCMCGRTG-3′), which were designed from alignments of gene sequences from the Riftia pachyptila endosymbiont and Rhodospirillum rubrum. PCRs were performed as described previously for the 16S ribosomal DNA sequence of strain MLHE-1 (26), using the following conditions: initial denaturation of template DNA at 94°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (1 min at 94°C), annealing (1 min at 49°C), and extension (3 min at 72°C).

Scanning electron microscopy.

The preparative methods for samples and the instrumentation employed for scanning electron microscopy have been noted previously (26, 32).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence from MLMS-1 has been assigned GenBank accession number AY459365.

RESULTS

Experiments with anoxic lake water.

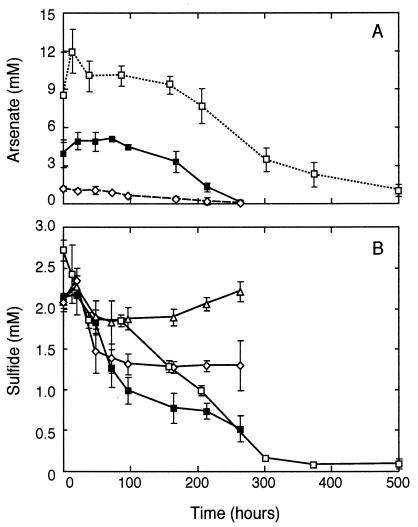

Bottom water from Mono Lake contained ∼2 mM dissolved sulfide. Additions of 1.0, 5.0, and 10 mM arsenate to samples resulted in the disappearance of both arsenate (Fig. 1A) and sulfide (Fig. 1B) with time. We did not monitor arsenite production in these initial experiments. No loss of sulfide occurred in controls incubated without added arsenate (Fig. 1B). In addition, filtered-sterilized or autoclaved controls with added arsenate did not demonstrate any loss of arsenate and only a relatively minor and slow loss of sulfide (∼0.2 mM total) over a comparable incubation period (data not shown). For example, after 300 h of incubation, these abiotic controls still had ∼1.8 mM remaining sulfide and 1.0, 4.8, or 10.0 mM remaining arsenate.

FIG. 1.

Loss of arsenate (A) and sulfide (B) in anoxic Mono Lake bottom water incubated at ambient sulfide concentrations. Symbols represent the means of three samples, and bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation. Concentrations of added arsenate were 0 mM (▵), 1 mM (◊), 5 mM (▪), and 10 mM (□).

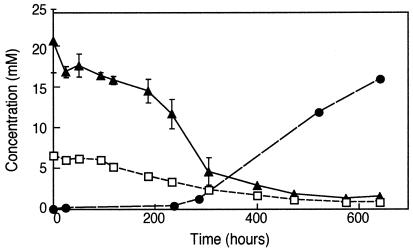

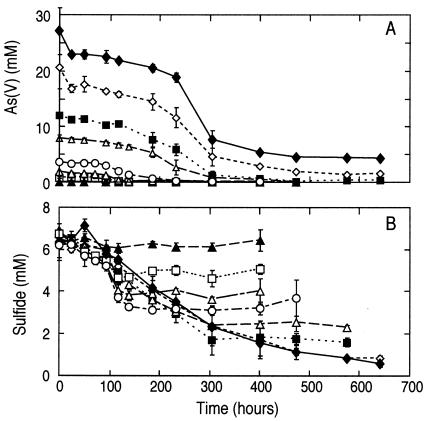

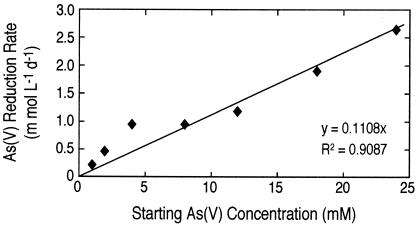

To demonstrate that the rate of arsenate reduction was arsenate limited, we carried out a series of time progress experiments with bottom water to which we added 4.0 mM sulfide (bringing its total to 6.0 mM) and various concentrations of arsenate. A typical time course for one of these experiments is given in Fig. 2, which demonstrates initial loss of both arsenate and sulfide, followed by production of arsenite. We were not able to follow production of sulfate as a product because of the high ambient concentration (∼130 mM) of this anion in lake water. The rates of arsenate reduction with time for various concentrations of added arsenate were plotted (Fig. 3A). Although all samples exhibited arsenate loss over the course of the incubation, the highest rates of arsenate reduction occurred after delayed time intervals of 100 to 250 h. For all these experiments, an amount of arsenite equivalent to the quantity of arsenate removed accumulated in the liquid phase (data not shown). Similarly, there was an increased loss of sulfide in the samples that corresponded with increased amounts of arsenate added at the outset (Fig. 3B). Again, loss of sulfide occurred neither in live samples incubated without added arsenate nor in live samples when the supply of arsenate was exhausted (Fig. 3B). In addition, no activity was noted in sulfide-supplemented, filter-sterilized controls that also contained arsenate concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 24.0 mM (data not shown). The rates of biological arsenate reduction increased linearly when extra arsenate was added (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Loss of arsenate (▴) and sulfide (□) and production of arsenite (•) over time in Mono Lake bottom water amended with both arsenate and sulfide. Symbols represent the means of three samples, and bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation. The absence of bars indicates that the error was smaller than the symbols.

FIG. 3.

Loss of arsenate (A) and sulfide (B) over time in Mono Lake bottom water at 6 mM sulfide with various concentrations of added arsenate. Symbols shown in panel A correspond to those in panel B except for the control without added arsenate (▴). Symbols represent the means of three samples, and bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation. Concentrations of added arsenate were 1 mM (□), 2 mM (▵), 4 mM (○), 8 mM (▵), 12 mM (▪), 18 mM (◊), and 24 mM (⧫).

FIG. 4.

Correlation of the highest arsenate reduction rates observed for results shown in Fig. 3 with the concentration of applied arsenate.

Preliminary description and autotrophic growth of strain MLMS-1.

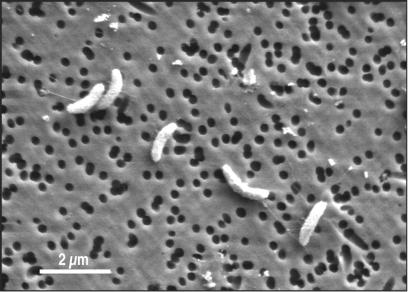

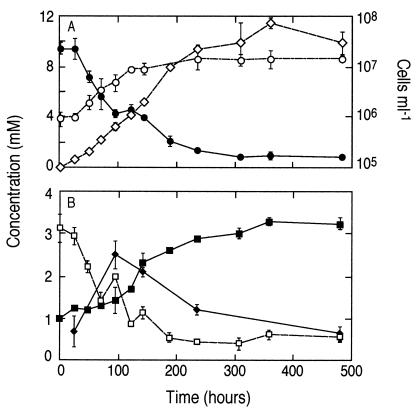

Strain MLMS-1 is a gram-negative, motile rod existing as single (or dividing) cells having individual lengths of 1.4 to 2.0 μm (Fig. 5). Growth was noted in mineral medium with sulfide as the electron donor and arsenate as the electron acceptor (Fig. 6A). A close concentration balance was noted with time as sulfide was oxidized to sulfate while arsenate was reduced to arsenite. By 10 days of incubation cell numbers had increased by more than 10-fold (Fig. 6A). The cell doubling time for growth under these conditions was slow (31.1 h; μ = 0.022 h−1). An unidentified, transient intermediate was observed on the HPLC chromatograms of the growing cultures but not on those of the controls. This unknown peak was subsequently identified by IC-ICPMS to be monothioarsenite, which increased over the first 100 h of incubation to ∼2.4 mM and then declined afterwards to ∼0.5 mM (Fig. 6B). Two other unknown species of thioarsenites were also detected by IC-ICPMS, but their concentrations were ≤∼0.2 mM (data not shown). Presumably these were dithioarsenite and trithioarsenite (arsenic trisulfide), but insufficient material was present in our samples to provide for an accurate S:As ratio to allow for confirmation. No growth was noted in controls that lacked arsenate, sulfide, or both of these substances, and furthermore these samples did not consume sulfide or arsenate or produce sulfate, thioarsenites, or arsenite (data not shown). We did not observe growth of strain MLMS-1 when hydrogen or methane was the electron donor instead of sulfide (data not shown). Given the relatively close phylogenetic affinity of strain MLMS-1 to sulfate reducers (see below), we attempted to grow it in sulfate medium. However, when sulfate was substituted for arsenate no growth occurred with hydrogen, acetate, hydrogen plus acetate, or lactate serving as the electron donor (data not shown). In addition, strain MLMS-1 was unable to grow on 10 mM arsenate with the following electron donors: hydrogen plus acetate, lactate, acetate, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.3% Casitone, and 0.3% Casamino Acids. No aerobic growth was noted (air headspace) with lactate or acetate as the electron donor or anaerobic growth with 10 mM nitrate and either sulfide or acetate as the electron donor.

FIG. 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of strain MLMS-1.

FIG. 6.

Growth of strain MLMS-1 on sulfide and arsenate. (A) Symbols: •, arsenate; ⋄, arsenite; ○, cells. (B) Symbols: □, sulfide; ♦, monothioarsenite; ▪, sulfate. Symbols represent the means of three samples, and bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation. The absence of bars indicate that the error was smaller than the symbols.

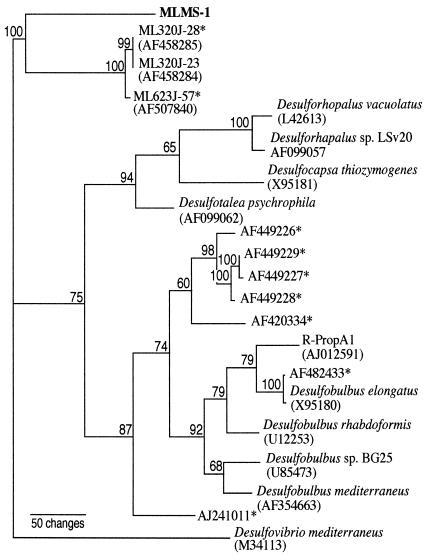

Phylogenetic alignment.

Strain MLMS-1 was found to be located in the δ-Proteobacteria, near to but significantly distinct from the recognized groups of sulfate reducers of the genera Desulfobulbus and Desulforhopalus (Fig. 7). The closest known (i.e., cultured and characterized) sulfate reducers were Desulfobulbus mediterraneus (91%) and Desulfobulbus rhabdoformis (88%). Strain MLMS-1 aligned much more closely (97%) with three unidentified clonal sequences previously recovered from the anoxic water column of Mono Lake (depths of 23 and 32 m) during July 2002 (12): ML 320J-28, ML 320J-23, and ML 623J-57.

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic tree (maximum parsimony) based on 16S ribosomal DNA sequence generated by neighbor joining analysis (PAUP) illustrating the taxonomic affiliation of MLMS-1. Bootstrap values are shown at the nodes, and accession numbers are in parentheses. Asterisks indicate environmental sequences.

Dark 14CO2 fixation and autotrophic gene sequences in strain MLMS-1.

Strain MLMS-1 was able to fix H14CO3− into cell carbon. Counts of incorporated 14C on filters were as follows (disintegrations per minute ± 1 standard deviation; n = 3): cells with sulfide plus arsenate, 5,760 ± 656; cells with arsenate, 514 ± 99; cells without arsenate or sulfide, 360 ± 69; and arsenate plus sulfide without cells, 17 ± 4. For the cells with both sulfide and arsenate, this represented incorporation of ∼0.05% of the HCO3− + CO3−2 pool, or about 144 nmol of carbon. Attempts to identify genes involved in carbon fixation were unsuccessful, as no PCR product was detected with the primers designed for amplification of RuBisCo.

DISCUSSION

In our previous field investigation of DAsR in Mono Lake (27) we demonstrated that in situ rates were highest (∼6 μmol liter−1day−1) just beneath the oxycline, where dissolved arsenate was ∼200 μM, and then decreased ∼10-fold with depth, where ambient arsenate was only ∼5 μM. These results suggested that DAsR activity in the bottom water was severely limited by the availability of arsenate, but notably not by the availability of an in situ electron donor(s). In our current study, the rates of DAsR clearly showed a linear increase with higher additions of arsenate (Fig. 4), which confirmed our earlier hypothesis. The highest rate of arsenate reduction in these samples was ∼2.6 mmol liter−1 day−1 at 24 mM added arsenate, or about 5,000-fold greater than the in situ DAsR activity observed in the anoxic bottom waters of Mono Lake. The long lag phases noted before these maximum rates of DAsR became evident (Fig. 3B) suggested that an increase in cell numbers of bacteria that could exploit the sulfide/arsenate couple was first required before their activity could be noted at these substrate concentrations. It also suggested that we should be able to successfully enrich for such an organism from samples of Mono Lake bottom water should we be able to demonstrate a biological coupling of DAsR with sulfide consumption.

Sulfide consumption in the bottom-water samples was clearly tied to the reduction of arsenate to arsenite (Fig. 1 and 3). The fact that it did not occur in the absence of added arsenate (Fig. 1B) or in killed controls demonstrates that it was acting as the electron donor. Arsenate can act as an oxidant of sulfide because the electrochemical potential of the arsenate/arsenite couple is +60 mV (2) while that of the sulfate/sulfide couple is −220 mV (39). While abiotic chemical reduction of arsenate with sulfide can occur at low pH (<4.0), it is kinetically unfavorable at the highly alkaline conditions of Mono Lake (28). Sulfide and arsenate loss in our experiments occurred at a 1:4 ratio (Fig. 1, 2, and 3), which indicates an eight-electron transfer reaction from the oxidation of 1 mol of sulfide with the reduction of 4 mol of arsenate. This stoichiometry suggests that sulfate was the end product of sulfide oxidation, but it could not be discerned over the high levels already present in the lake water. The formation of sulfate from sulfide was subsequently confirmed in growth experiments with strain MLMS-1 (see below).

Isolation of strain MLMS-1 proved to be rather easy to achieve in liquid medium, although we were not able to get it to grow on a solidified medium of the same composition. Presumably we were able to achieve purity by serial dilution because all that was really required was the addition of large amounts of the two noxious inorganic nutrients (sulfide and arsenate), which when coupled with accumulation of an even more toxic end product (arsenite), probably prevented the growth of any potential satellite heterotrophs that could have complicated such a simple serial dilution approach. Every mole of sulfide oxidized to sulfate by strain MLMS-1 required the reduction of 4 mol of arsenate to arsenite (Fig. 5). This indicates that growth occurred according to reaction 1 (39, 41):

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

The energy yield for this reaction is comparable to that which we calculate for growth on arsenate by various heterotrophs that oxidize lactate to acetate at circumneutral pH, as given in reaction 2 above (16, 17, 21). A similar calculation for the heterotrophic haloalkaliphiles Bacillus arsenicoselenatis and Bacillus selenitireducens, both isolated from Mono Lake (35), gives a ΔGo′ of −156.8 kJ/reaction or −39.2 kJ/mol e− equivalent. This yield is lower than the circumneutral calculations, owing primarily to the lower ΔGfo of −587 kJ for the charged arsenite anion (H2AsO3−) prevalent at high pH rather than the uncharged species (H3AsO3; ΔGfo = −646 kJ) prevalent at neutral pH (30). However, both of these heterotrophic arsenate respirers had much faster doubling times (4 to 5 h) than that of strain MLMS-1 (30 h). Therefore, the much slower growth rate exhibited by strain MLMS-1 when compared with heterotrophic arsenate respirers (both circumneutral and alkaliphilic strains) cannot be explained by thermodynamic constraints. A more instructive comparison, therefore, can be made to the growth of strain MLHE-1, a member of the γ-Proteobacteria that was also isolated from Mono Lake (26). When grown as a chemoautotroph using arsenite as its electron donor and nitrate as its electron acceptor it had a doubling time of 8.1 h, but when sulfide was substituted for arsenite the doubling time increased to 74 h. We conclude that the slow growth rates for strains MLMS-1 and MLHE-1 on sulfide were most likely caused by metabolic constraints related to the anaerobic oxidation of this electron donor to sulfate rather than to any thermodynamic limitations.

We noted the transient accumulation of thioarsenites during growth of strain MLMS-1, of which monothioarsenite was the most abundant (Fig. 6B). It is not likely, however, that the thioarsenites were directly produced and consumed by the metabolism of strain MLMS-1. Thioarsenites, although soluble in carbonate-rich, high-pH water like that of Mono Lake, are generally unstable and decompose readily (28, 40). Therefore, we believe that their occurrence merely reflected favorable chemical conditions: first for their emergence and then for their subsequent decomposition, owing indirectly to the metabolism of strain MLMS-1.

Since the original reports of arsenate respiration occurring in the genus Sulfurospirillum (1, 16, 33), about 20 new species of phylogenetically diverse prokaryotes (including strain MLMS-1) have been isolated that can grow via dissimilatory reduction of arsenate (16a, 25, 37, 38; A. Liu, E. Garcia-Dominguez, E. D. Rhine, and L. Y. Young, submitted for publication). All isolates obtained from the domain Bacteria have thus far been characterized as heterotrophs in that they use simple organics (e.g., lactate and acetate) or in some cases aromatics (16a) as their electron donors. Many of these species can also use hydrogen, but will only grow if a basic carbon skeleton, such as acetate, is additionally provided. Hydrogen-linked chemoautotrophy was reported for arsenate-respiring hyperthermophilic Crenarchaeota species (11), although claim of chemoautotrophy in these two species of Pyrobaculum was not rigorously tested. Recently, chemoautotrophic growth with H2, using arsenate as the electron acceptor, was reported for strain Y5 (low-G+C gram-positive bacterium; domain Bacteria) and supported by detection of the CO2-fixing RuBisCo type II cbbM gene by PCR (16a). Strain MLMS-1, however, is unusual in that it will not use H2 as an electron donor for arsenate reduction. Indeed, our preliminary results suggest that its metabolism may be confined to the use of sulfide and arsenate, respectively, as the only electron donor and acceptor that will sustain its growth. If confirmed, strain MLMS-1 would represent the first example of an obligate arsenate-respiring bacterium that is also an obligate chemolithoautotroph.

The ability of anaerobic prokaryotes to grow as chemoautotrophs requires that they employ as their electron acceptors inorganic ions that have higher electrochemical potentials than their electron donors. This has been shown for a variety of novel isolates, including sulfate reducers that oxidize phosphites (29), nitrate respirers that oxidize ferrous iron (34), and in the case of strain MLHE-1 from Mono Lake, a facultative nitrate respirer than can oxidize arsenite, hydrogen, and sulfide (26). Although we were unable to amplify gene sequences for RuBisCo from strain MLMS-1, this does not necessarily mean that this enzyme was absent, as the primers we employed may not have been well suited. However, our results that demonstrate growth in inorganic medium when coupled with the results of the H14CO3− fixation experiments clearly show that this microorganism is a chemoautotroph, and its pathway of CO2 fixation will be the subject of future investigations.

The closest phylogenetic relatives of strain MLMS-1 that are held as pure cultures are sulfate reducers of the δ-Proteobacteria (Fig. 7). Although there are examples of both gram-positive and gram-negative sulfate reducers that can respire arsenate (17, 21) these were characterized as heterotrophs rather than autotrophs. Indeed, because strain MLMS-1 is so distant from the genus Desulfobulbus (88 to 91% sequence similarity), when taken with its inability to grow on sulfate, it suggests that it belongs within an entirely new genus. The fact that the three clonal sequences most closely related to MLMS-1 (97% similarity) have been detected in the anoxic water column of Mono Lake (12) further indicates that these uncultured strains are also capable of this mode of chemoautotrophic growth within the lake itself. Furthermore, our results stress the importance of coupling traditional culturing with biogeochemical experimentation when attempting to define the ecological niches for novel amplified environmental clones of small-subunit DNA sequences.

It was calculated that annual water column arsenate reductase activity could mineralize 8 to 14% of annual primary production in Mono Lake, with another 41% contributed by water column sulfate reduction (27). What is not known is the nature of the electron donors that drive these two processes or how they may vary between heterotrophic and autotrophic components with the seasonal cycles occurring in Mono Lake. The biological oxidation of sulfide with arsenate ions also suggests a mechanism by which the supply of sulfate to sulfate reducers can be sustained. While this is clearly not important in Mono Lake, a sulfate-rich (130 mM) environment, there may be low-sulfate locales (e.g., hot springs and freshwater lakes) where such an anaerobic regeneration process could prove to be significant.

The question of what process(es) drives arsenic mobilization in subsurface drinking water aquifers is a problem that affects the health of millions of people worldwide, notably in Bangladesh and East Bengal, India (22, 31). The current evidence suggests that this is a microbially driven process that results in the dissimilatory reduction of arsenate along with some of the solid-phase Fe(III) to which it is adsorbed. However, the electron donors involved in this reaction have not been clearly identified, although they were hypothesized to be derived either from decomposition of buried peat deposits (18, 23) or from hydrologic drawdown of surface agricultural wastes (8). Both of these hypotheses, therefore, focused on organic matter-derived electron donors that could fuel heterotrophic DAsR. The possibility that inorganic molecules (e.g., sulfide and hydrogen) might fuel DAsR in an otherwise organic-poor but mineral-rich subsurface aquifer has not been previously postulated or tested.

If autotrophic bacteria that can exploit the sulfide/arsenate couple like strain MLMS-1 can be found in such nutrient-poor environments as subsurface aquifers, it would have implications beyond contaminant hydrology. Renewed interest in “exobiology” has been stimulated by the prospects that microbial life may have evolved on other planetary bodies in our solar system, most notably those that once had (or now have) liquid water and the equivalent of an active volcanism. This would include the surface of early Mars and beneath the ice sheet of present-day Europa. One proposed means of searching for evidence of such exobiological communities involves detecting their chemical “signatures” by prospecting for inorganic biological redox couples in either living layered communities or their fossilized remnants (20). Therefore, the arsenic/sulfur couple would be another redox pair to be on the lookout for when the designs for such exploration missions are conceived.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to B. F. Taylor and L. Young for their constructive comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We thank H. Gürleyük at Frontier Geosciences for performing the analyses of the thioarsenite species and J. Lisak and N. Bano for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the USGS National Research Program (R.S.O) and grants from the NASA Exobiology Research Program (R.S.O and J.F.S) and the Microbial Observatories Program of NSF (J.T.H).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmann, D., A. L. Roberts, L. R. Krumholz, and F. M. M. Morel. 1994. Microbe grows by reducing arsenic. Nature 371:750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bard, A. J., R. S. Parsons, and J. Jordan. 1987. Standard potentials in aqueous solutions. Marcell Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Cline, J. D. 1969. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 14:454-459. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis, S. E., and R. Haselkorn. 1983. Isolation and sequence of the gene for the larger subunit of ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase from the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:1835-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsaied, H., and T. Naganuma. 2001. Phylogenetic diversity of ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit genes from deep-sea microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1751-1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felsenstein, J. 1988. Phylogenies from molecular sequences: inference and reliability. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22:521-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannoni, S. 1991. Polymerase chain reaction, p. 177-204. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 8.Harvey, C. F., C. H. Swartz, A. B. M. Badruzzaman, N. Keon-Blute, W. Yu, M. A. Ali, J. Jay, R. Beckie, V. Niedan, D. Brabander, P. M. Oates, K. N. Ashfaque, S. Islam, H. F. Hemond, and M. F. Ahmed. 2002. Arsenic mobility and groundwater extraction in Bangladesh. Science 298:1602-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobbie, J. E., R. L. Daley, and S. Jaspar. 1977. Use of Nuclepore filters for counting bacteria for fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 33:1225-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoeft, S. E., F. Lucas, J. T. Hollibaugh, and R. S. Oremland. 2002. Characterization of bacterial arsenate reduction in the anoxic bottom waters of Mono Lake, California. Geomicrobiol. J. 19:1-19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huber, R., M. Sacher, A. Vollmann, H. Huber, and D. Rose. 2000. Respiration of arsenate and selenate by hyperthermophilic archaea. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:305-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humayoun, S. B., N. Bano, and J. T. Hollibaugh. 2003. Depth distribution of microbial diversity in Mono Lake, a meromictic soda lake in California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1030-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeannmougin, F., J. D. Thompson, M. Gouy, D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1998. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:403-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joye, S. B., T. L. Connell, L. G. Miller, R. Jellison, and R. S. Oremland. 1999. Oxidation of ammonia and methane in an alkaline, saline lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44:178-188. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lane, D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115-176. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 16.Laverman, A. M., J. Switzer Blum, J. K. Schaefer, E. J. P. Phillips, D. R. Lovley, and R. S. Oremland. 1995. Growth of strain SES-3 with arsenate and other diverse electron acceptors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3556-3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Liu, A., E. Garcia-Dominguez, E. D. Rhine, and L. Y. Young. A novel arsenate respiring isolate that can utilize aromatic substrates. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Macy, J. M., J. M. Santini, B. V. Pauling, A. H. O'Neill, and L. I. Sly. 2000. Two new arsenate/sulfate-reducing bacteria: mechanisms of arsenate reduction. Arch. Microbiol. 173:49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McArthur, J. M., P. Ravenscroft, S. Safiula, and M. F. Thirlwall. 2001. Arsenic in groundwater: testing pollution mechanisms for sedimentary aquifers in Bangladesh. Water Resources Res. 37:109-117. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, L. G., R. Jellison, R. S. Oremland, and C. W. Culbertson. 1993. Meromixis in hypersaline Mono Lake, California: 3. Biogeochemical response to stratification and overturn. Limnol. Oceanogr. 38:1040-1051. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nealson, K., and W. Berelson. 2003. Layered microbial communities and the search for life in the universe. Geomicrobiol. J. 20:451-462. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman, D. K., E. K. Kennedy, J. D. Coates, D. Ahmann, D. J. Ellis, D. R. Lovley, and F. M. M. Morel. 1997. Dissimilatory arsenate and sulfate reduction in Desulfotomaculum auripigmentum sp. nov. Arch. Microbiol. 168:380-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nickson, R., J. McArthur, W. Burgess, K. M. Ahmed, P. Ravenscroft, and M. Rahman. 1998. Arsenic poisoning of Bangladesh groundwater. Nature 395:338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickson, R. T., J. M. McArthur, P. Ravenscroft, W. S. Burgess, and K. M. Ahmed. 2000. Mechanism of arsenic poisoning of groundwater in Bangladesh and West Bengal. Appl. Geochem. 15:403-415. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oremland, R. S., J. F. Stolz, and J. T. Hollibaugh. 2004.. The microbial arsenic cycle in Mono Lake, California. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 48:15-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Oremland, R. S., and J. F. Stolz. 2003. The ecology of arsenic. Science 300:939-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oremland, R. S., S. E. Hoeft, J. M. Santini, N. Bano, R. A. Hollibaugh, and J. T. Hollibaugh. 2002. Anaerobic oxidation of arsenite in Mono Lake water and by a facultative, arsenite-oxidizing chemoautotroph, strain MLHE-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4795-4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oremland, R. S., P. R. Dowdle, S. Hoeft, J. O. Sharp, J. K. Schaefer, L. G. Miller, J. Switzer Blum, R. L. Smith, N. S. Bloom, and D. Wallschlaeger. 2000. Bacterial dissimilatory reduction of arsenate and sulfate in meromictic Mono Lake, California. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 64:3073-3084. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rochette, E. A., B. C. Bostick, G. Li, and S. Fendorf. 2000. Kinetics of arsenate reduction by dissolved sulfide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:4714-4720. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schink, B., and M. Friedrich. 2000. Phosphite oxidation by sulfate reduction. Nature 406:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smedley, P. L., and D. G. Kinniburgh. 2002. A review of source, behavior and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Appl. Geochem. 17:517-568. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith, A., E. Lingas, and M. Rahman. 2000. Contamination of drinking-water by As in Bangladesh. Bull. W.H.O. 78:1093-1103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, R. L., F. S. Strohmaier, and R. S. Oremland. 1985. Isolation of anaerobic oxalate degrading bacteria from freshwater lake sediments. Arch. Microbiol. 14:8-13. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stolz, J. F., D. J. Ellis, J. Switzer Blum, D. Ahmann, R. S. Oremland, and D. R. Lovley. 1999. Sulfurospirillum barnesii sp. nov., Sulfurospirillum arsenophilus sp. nov., and the Sulfurospirillum clade in the epsilon Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1177-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Straub, K. L., M. Benz, B. Schink, and F. Widdel. 1996. Anaerobic, nitrate-dependent microbial oxidation of ferrous iron. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1458-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Switzer Blum, J., A. Burns Bindi, J. Buzzelli, J. F. Stolz, and R. S. Oremland. 1998. Bacillus arsenicoselenatis sp. nov., and Bacillus selenitireducens sp. nov.: two haloalkaliphiles from Mono Lake, California that respire oxyanions of selenium and arsenic. Arch. Microbiol. 171:19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swofford, D. L. 1998. PAUP. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony and other methods, version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass..

- 37.Takai, K., H. Kobayashi, K. H. Nealson, and K. Horikoshi. 2003. Deferribacter desulfuricans sp. nov., a novel sulfur-, nitrate- and arsenate-reducing thermophile isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:839-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takai, K., H. Hirayama, Y. Sakihama, F. Inagaki, Y. Yamato, and K. Horikoshi. 2002. Isolation and metabolic characteristics of previously uncultured members of the order Aquificales in a subsurface gold mine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3046-3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thauer, R. K., K. Jungermann, and K. Decker. 1977. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 41:100-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkin, R. T., D. Wallschläger, and R. G. Ford. 2003. Speciation of arsenic in sulfidic waters. Geochem. Trans. 4:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods, T. L., and R. M. Garrels. 1987. Thermodynamic values at low temperature for natural inorganic materials: an uncritical summary. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.